Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) can initiate immune responses by presenting exogenous antigens via both major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II pathways to T cells. Lysosomal activity plays an important role in modulating the balance between the two pathways. The transcription factor TFEB regulates lysosomal function by inducing lysosomal activation. Here, we report that TFEB expression inhibited the presentation of exogenous antigen by MHC class I while enhancing presentation via MHC class II. TFEB promoted phagosomal acidification and protein degradation. Furthermore, we show that TFEB activation was regulated during DC maturation, and phagosomal acidification was impaired in TFEB-silenced DCs. Our data indicate that TFEB is a key player differentially regulating the presentation of exogenous antigens by DCs.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are considered to be the most potent antigen presenting cells (APCs) for inducing adaptive immune responses 1. APCs present peptides derived from cytosolic antigens bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and exogenous antigens on MHC class II molecules for recognition by CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, respectively 2. However, DCs also have the ability to present peptides derived from exogenous internalized antigens on MHC class I molecules, a process referred to as cross-presentation 3. Cross-presentation, or cross-priming, is critical for the initiation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses against tumor cells, bacteria or viruses that do not directly infect DCs 3, 4.

In most APCs, early endosomes or nascent phagosomes that contain newly internalized antigens undergo a maturation process in which the organelle pH is reduced and proteolytic capacity increases 5. In DCs, however, this process needs to be carefully modulated, because extensive lysosomal proteolysis is incompatible with cross-presentation 6 and favors antigen presentation via MHC class II 7. Partial degradation is thought to facilitate cross-presentation by allowing ingested antigens to escape the endocytic or phagocytic pathways and enter the cytoplasm 8, where further degradation by the proteasome occurs 9. This is followed by translocation of resulting antigenic peptides into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 10, or perhaps phagosomal or endosomal compartments 11, where they can bind to MHC class I molecules 12, 13.

To sustain antigen stability, DCs exhibit a low capacity for phagosomal degradation compared to macrophages, including limited lysosomal acidification 14 and low expression of lysosomal proteases 15. These unique features endow DCs, particularly CD8α+ DCs in the mouse, with a high capacity for cross-presentation both in vitro and in vivo 3. However, upon stimulation by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands such as LPS, DC phagosomes acquire mature lysosomal properties 14, shifting the balance toward the induction of MHC class II-restricted antigen presentation and a reciprocal decrease in cross-presentation 16. Consistent with this, macrophages, known to have very high lysosomal degradative capacity, are generally less efficient in performing cross-presentation, while they can effectively present antigens via MHC class II 17. As such, lysosomal activity is a critical factor in determining the fate of an internalized antigen and regulating the balance between the two exogenous antigen presenting pathways in DCs. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

The transcription factor TFEB transcriptionally regulates lysosomal biogenesis and function in a variety of cell types in response to various stimuli, such as growth factors and nutrients 18. Expression analysis suggests that TFEB is a central regulator of cellular degradative pathways and, due to its role in stress responses, enhancement of TFEB activity has emerged as a potential therapeutic approach for a number of lysosomal and protein aggregation disorders 19. TFEB positively regulates the expression of lysosomal genes involved in phagocytosis and lipid catabolism 19. It is also activated during bacterial infection of macrophages 20. However, the role of TFEB in antigen presentation remains unclear. Here we report that this transcription factor is a key regulator of the presentation of exogenous antigen by APCs. Up-regulation of TFEB during DC maturation leads to enhanced lysosomal proteolytic activity, a reduction in cross-presentation and an increase in MHC class II presentation. Additionally, experimental down-regulation of TFEB expression in macrophages leads to an increase in MHC class I-restricted cross-presentation, demonstrating that TFEB plays a critical role in regulating antigen presentation by APCs.

Results

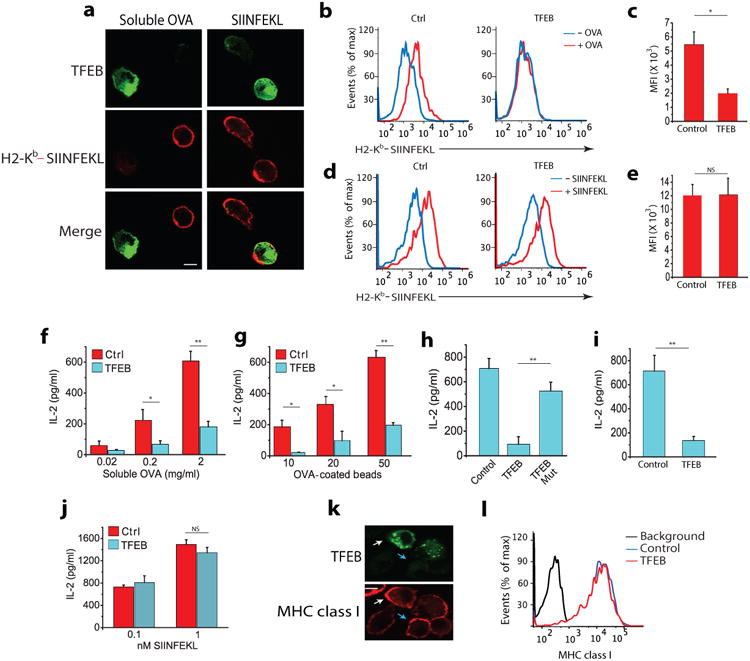

TFEB expression reduces cross-presentation in DCs

We first examined the effect of TFEB on MHC class I-restricted cross-presentation in bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) using ovalbumin (OVA) antigen. DCs were retrovirally transduced with vectors expressing either TFEB-EGFP or EGFP alone (control-EGFP). Transduction efficiency was 80%-85% for each experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and further purification of transduced BMDCs was not required. We incubated TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs with soluble OVA for three hours and then examined the surface expression of H2-Kb molecules specifically associated with the OVA-derived peptide SIINFEKL (residues 257-264) by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy using the mAb 25.D1 21. Non-transduced BMDCs expressed Kb-SIINFEKL complexes on the cell surface, while Kb-SIINFEKL complexes were not detectable on the surface of TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs (Fig. 1a). However, Kb-SIINFEKL complexes were readily detectable on both TFEB-EGFP-transduced and non-transduced BMDCs incubated with SIINFEKL peptide, which binds in a processing-independent manner by simple exchange (Fig. 1a). In a similar experimental set-up, we also used flow cytometry to assess Kb-SIINFEKL expression on transduced (EGFP+) BMDCs. Control-EGFP-transduced BMDCs expressed surface Kb-SIINKEKL following incubation with soluble OVA, while TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs did not (Fig. 1b,c). The amount of surface Kb-SIINFEKL was equally high on BMDCs transduced with either control-EGFP or TFEB-EGFP after incubation with free peptide (Fig. 1d,e). These data indicate that TFEB expression reduces the cross-presentation capacity of DCs.

Figure 1. TFEB inhibits cross-presentation in DCs.

(a) Immunofluorescence of surface expression of Kb-SIINFEKL complexes in non-permeabilized BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP assessed by staining with mAB 25.D1 following incubation with 2mg/ml soluble OVA or 2nM free SIINFEKL peptide for 3 hours. (b-e) Flow cytometry analysis of Kb-SIINFEKL complex expression on the surface of BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP or control-EGFP vectors after they were incubated with OVA protein or free SIINFEKL peptide. (f,g) Cross-presentation-dependent T cell stimulation in response to TFEB-EGFP and control-EGFP transduced BMDCs incubated with soluble OVA or 3μm OVA-coated beads. The level of cross-presentation was determined by measuring the amount of IL-2 produced by B3Z cells by ELISA (h) Cross-presentation-dependent T cell stimulation in response to TFEB or nucleus translocation defective mutant TFEBMut-transduced BMDCs incubated with OVA. (i) TFEB-mediated cross-presentation of a viral epitope; TFEB transduced BMDCs were incubated with inactivated HSV-1 for 5 hours, fixed and co-cultured with T cells isolated from the spleen of gBT mouse. (j) Presentation of SIINFEKL peptide by TFEB-transduced and control BMDCs. (k,j) MHC class I (Kb) surface expression on BMDCs transduced with TFEB, evaluated on non-permeabilized cells by confocal microscopy (k) and flow cytometry (j). For all panels the data represents the mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments (cells isolated from at least three different mice) unless otherwise indicated. *P < 0.05 (Student's t-test).

Next, we determined if TFEB affects cross-presentation-dependent T cell stimulation. TFEB-EGFP or control-EGFP transduced BMDCs were incubated with different concentrations of soluble OVA or OVA-coated latex beads for six hours followed by incubation with B3Z hybridoma T cells, which specifically recognize Kb-SIINFEKL complexes, and T cell activation was assayed by measuring IL-2 production. Cross-presentation by TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs was strongly inhibited compared to control-EGFP-transduced BMDCs for both soluble OVA (Fig. 1f) and OVA-coated beads (Fig. 1g). The uptake of soluble OVA (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and OVA-coated beads (Supplementary Fig. 1c), SIINFEKL peptide-induced T cell activation (Fig. 1j) and surface expression of Kb molecules (Fig. 1k-l) were all comparable between TFEB-EGFP and control-EGFP transduced BMDCs, indicating that the reduced cross-presentation observed in TFEB-overexpressing DCs was not due to defects in antigen uptake or MHC class I expression.

Transcription of TFEB-regulated genes depends on its localization to the nucleus 18. We therefore determined the effect of TFEB containing inactivating mutations in the nuclear localization signal (TFEBMut) on cross-presentation 22. Although both wild-type protein (WT-TFEB) and TFEBMut constructs were equally expressed (Supplementary Fig. 1d), cross-presentation by BMDCs transduced with TFEBMut was comparable to BMDCs transduced with control-EGFP (Fig. 1h), indicating that TFEB translocation to the nucleus is required for inhibition of cross-presentation. We also examined the cellular distribution of mutant and wild-type TFEB in BMDCs incubated with opsonized OVA coated beads. Transduced WT-TFEB translocated to the nucleus within 30 minutes of the initiation of phagocytosis, while TFEBMut remained in the cytoplasm (Supplementary Fig. 1e), demonstrating that TFEB nuclear localization is required to inhibit cross-presentation.

To extend the analysis beyond the OVA presentation system, we next determined whether TFEB is important for the cross-presentation of viral antigens. Glycoprotein B (gB) from herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is a well characterized MHC class I antigen with a defined epitope that is recognized by CD8+ naive T cells. BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP were incubated for six hours with inactivated HSV-1 virus particles, followed by overnight co-culture with T cells enriched from the spleens of transgenic gBT mice, which express an HSV-1-specific T cell receptor (TCR). gBT transgenic CD8+ T cells recognize the immunodominant peptide gB498–505, derived from HSV glycoprotein B (gB), associated with H2-Kb 23. TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs were defective in stimulating gBT CD8+ T cells compared to BMDCs transduced with control-EGFP vector (Fig. 1i) indicating that TFEB expression inhibited the cross-presentation of the gB epitope. Together, these data show that TFEB activation inhibits cross-presentation in DCs.

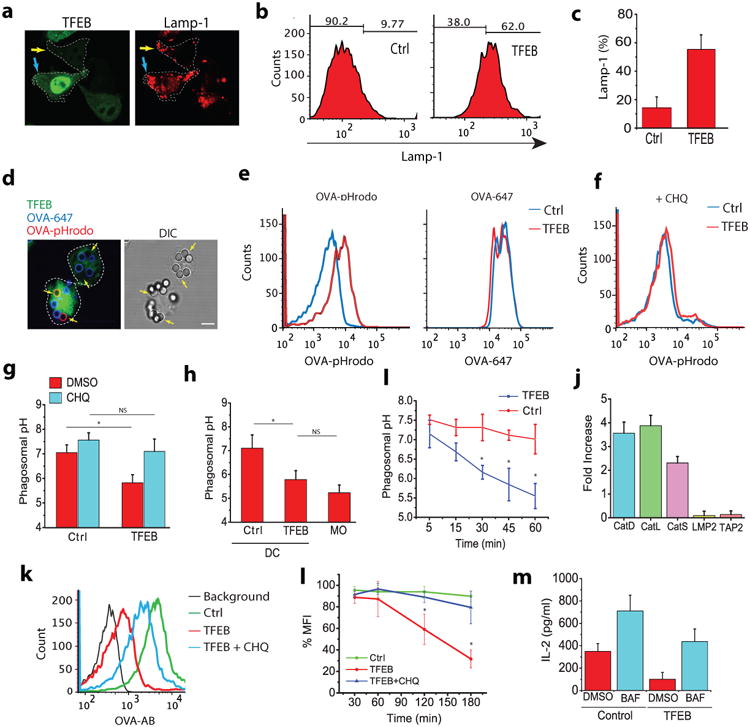

TFEB induces phagosomal acidification and proteolysis in DCs

Because TFEB is a transcriptional factor that regulates lysosomal functions 19, we tested whether its role in regulating cross-presentation might reflect an effect on the degradation of exogenous antigens. Immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry analysis indicated that that TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs contain a larger number of lysosomal compartments than control-EGFP-transduced cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a-b). TFEB is known to regulate lysosomal pH in other cell types 24. To assess if TFEB induced the phagosomal acidification and degradation of internalized particulate antigens, we used a flow cytometry-based technique. BMDCs were allowed to ingest polystyrene beads coated with OVA conjugated with a pH-sensitive dye (pHrodo succinimidyl ester; OVA-pHrodo) and OVA conjugated with a pH-insensitive dye (Alexa fluor 647; OVA-647). After 60 minutes, BMDCs were collected and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified for each dye using flow cytometry (Fig. 2a-c). The ratio in fluorescence intensity between the two dyes reflects the environmental pH. The pH of the OVA-coated bead-containing phagosomes was estimated by comparing the MFIs to a standard curve (Supplementary Fig. 3a) 25. BMDCs transduced with the control-EGFP vector displayed a high phagosomal pH (∼7.2), as shown previously 25. However, the phagosomes of BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP were much more acidic (pH∼5.8). Chloroquine (CHQ), which neutralizes lysosomes, impaired the TFEB-induced acidification (Fig. 2c-d). Phagosomes in macrophages have a much lower pH than DCs 25, but those in TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs were less acidic than those in macrophages (Fig. 2e). In control-EGFP-transduced BMDCs the pH remained relatively unchanged over time, while the phagosomal pH continuously decreased after 15 min in TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs (Fig. 2f). This is consistent with the active induction of acidification by TFEB, most likely it enhances expression of the subunits of the vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) responsible for acidification26.

Figure 2. TFEB induces phagosomal acidification and acidification in DCs.

(a) Confocal microscopy image showing a TFEB-transduced and a non-transduced BMDC containing OVA-pHrodo (pH dependent) and OVA-647 (pH independent) beads. Yellow arrows point to the OVA-pHrodo beads (b) Phagosomal pH analysis of TFEB-transduced BMDCs using OVA-pHrodo and OVA-647 beads measured by flow cytometry. (c,d) The influence of CHQ on TFEB-induced acidification in BMDCs. (e) TFEB-induced phagosomal acidification in BMDCs compared to bone marrow derived macrophages. (f) Kinetics of phagosomal acidification in TFEB-transduced and non-transduced BMDCs. (g) The effects of TFEB on the expression of proteases involved in lysosomal antigen processing and proteins involved in cross-presentation (h) The influence of TFEB on phagosomal degradation. The amount of OVA remained on beads ingested by TFEB-EGFP-transduced DCs or control-EGFP transduced DCs was evaluated by flow cytometry using an OVA antibody. (i) Kinetics of phagosomal degradation in TFEB transduced and non-transduced DCs. (j) The TFEB-mediated decrease in cross-presentation depends on lysosomal acidification. Cross-presentation was partially rescued in TFEB-transduced cells after bafilomycin treatment. For all panels unless otherwise indicated the data represents the mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments (cells isolated from at least three different mice), unless otherwise indicated. *P < 0.05 (Student's t-test).

We next assessed the TFEB-mediated induction of genes encoding lysosomal proteases by qRT-PCR in BMDCs. Expression of mRNAs for lysosomal cathepsins D, L and S, which are involved in lysosomal antigen degradation in APCs, was strongly up-regulated by TFEB expression (Fig. 2g). However, TFEB expression had no effect on the level of LMP2, which encodes an interferon-γ-inducible immunoproteasome subunit, or of TAP2, a subunit of the dimeric peptide transporter TAP, which translocates proteasomally-generated peptides into the ER for MHC class I loading (Fig. 2g) 2, 27. To evaluate the functional consequences of TFEB overexpression in BMDCs, we used a flow cytometry based assay to monitor phagosomal degradation. After phagocytosis of polystyrene beads coated with OVA, BMDCs were lysed and the intact residual OVA was assessed by flow cytometry using a polyclonal OVA-specific antibody. We observed significantly less residual OVA on the beads internalized by BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP compared to BMDCs transduced with control-EGFP vector (Fig. 2h,i). OVA degradation in BMDCs was almost completely blocked by CHQ (Fig. 2h,i). To directly address whether the role of TFEB in cross-presentation is mediated by the induction of lysosomal activity we inhibited lysosomal acidification or degradation in BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP. Treatment with bafilomycin, an endosomal acidification inhibitor, increased cross-presentation in BMDCs transduced with control-EGFP vector, and partially rescued cross-presentation in TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs (Fig. 2j), as evaluated by T cell activation, suggesting that TFEB inhibits cross-presentation by increasing lysosomal acidification. Similar results were also obtained with the lysosome neutralizing agent CHQ (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Collectively, these data show that TFEB expression in DCs enhances antigen degradation in the phagosomes by inducing the expression of lysosomal proteases and phagosomal acidification.

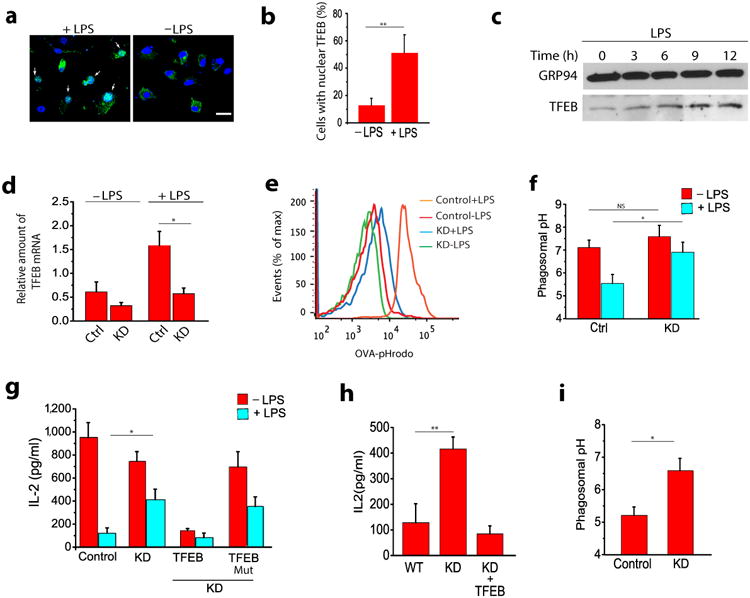

TFEB inhibits the cross-presentation induced by DC maturation

LPS and other TLR ligands induce the maturation of immature DCs (iDCs) to mature DCs (mDCs) 28. One of the most distinct differences between immature and mature DCs in vitro is that immature DCs are extremely efficient in cross-presentation, but present MHC class II-restricted antigens poorly, while mature DCs are less efficient at cross-presentation but have a high capacity for MHC-class II presentation 29. Lysosomal function and acidification changes induced by DC maturation constitute the major regulators of these presentation pathways 14, 15. We therefore addressed whether TFEB activation is responsible for the changes in cross-presentation capacity induced by DC maturation. TFEB activation is regulated by phosphorylation which results in its translocation to nucleus. We observed a strong nuclear translocation of TFEB in LPS treated BMDCs compared to non-treated cells, similar to recent observations in cornea cells 30 (Fig. 3a-b). TFEB activation and its localization to nucleus exerts a positive effect on its own transcription through an autoregulatory loop 26, and we also found that stimulation of BMDCs with LPS for 6 hours induced the up-regulation of TFEB mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and protein (Fig. 3c) expression 30. We also examined the regulation of TFEB expression in BMDCs in response to stimulation with other TLR ligands. TFEB was up-regulated by exposure to crude Salmonella LPS, a TLR4 ligand, but was also up-regulated by the TLR2 ligands peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), consistent with published data that infecting macrophages with S. aureus leads to TFEB activation 20. However, CpG, a TLR9 ligand, had no effect on TFEB expression (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c).

Figure 3. TFEB is involved in LPS induced inhibition of cross-presentation in DCs.

(a) TFEB activation in BMDCs in response to LPS as evaluated by its translocation to the nucleus. (b) Quantification of TFEB localization from panel a. Graph represents data obtained from 50 cells for each treatment. (c) TFEB expression by BMDCs in response to LPS as evaluated by western blot using a polyclonal antibody against endogenous TFEB. (d) shRNA-mediated silencing of endogenous TFEB in untreated and LPS-treated BMDCs. (e) Representative histograms showing flow cytometry analysis based pH measurements of the phagosomes in WT and TFEBKD DCs. (f) LPS-induced acidification of phagosomes is significantly inhibited in TFEBKD DCs. (g) Overnight LPS treatment decreases cross-presentation in BMDCs while silencing TFEB significantly reverses this effect; re-expression of TFEB in the TFEBKD cells restores inhibition of cross-presentation, while expression of TFEBMut, fails to do so; silencing TFEB has no effect on cross-presentation by immature BMDCs. (h) Effect of TFEB silencing on cross-presentation by macrophages (i) Effect of TFEB silencing on phagosomes pH in macrophages. For all panels unless otherwise indicated the data represents the mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments (cells isolated from at least three different mice), unless otherwise indicated. *P < 0.05 (Student's t-test).

We next determined if loss of endogenous TFEB regulates cross-presentation by analyzing the effect of shRNA-mediated silencing of TFEB on both maturation-induced lysosomal activity and cross-presentation by BMDCs. A TFEB-specific shRNA reduced the expression of basal TFEB mRNA levels, but, more significantly, the induction of TFEB mRNA expression in LPS-treated BMDCs was reduced by almost three-fold compared to DCs expressing a control shRNA, as shown by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3d). TFEB knockdown had no effect on LPS-induced BMDC maturation as assessed by the surface expression of CD86 (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Treating DCs with LPS for 24 hours significantly decreased cross-presentation and increased phagosomal acidification in BMDCs transduced with control vector, consistent with previous publications 28, and the LPS-mediated decrease in cross-presentation was partially restored in TFEBKD BMDCs (Fig. 3g). TFEB silencing had a minor effect on the cross-presentation ability of immature DCs. Re-constitution of TFEB expression by transducing TFEB-EGFP in the TFEBKD BMDCs restored cross-presentation inhibition, while expression of the nuclear translocation mutant TFEBMut failed to do so (Fig. 3g). Conversely, silencing the expression of TFEB in bone marrow derived macrophages (BMMs) (Supplementary Fig. 5a), which are poor cross-presenting cells, enhanced their ability to cross-present OVA compared to cells transduced with control vector (Fig. 3h), while simultaneously increasing their phagosomal pH (Fig. 3i). Re-constitution of TFEB expression in the TFEBKD BMMs reduced cross-presentation to its original levels (Fig. 3h). TFEBKD BMMs also showed decreased expression of cathepsin L and D transcripts compared to control cells (Supplementary Fig. 5b,c). Overall, these data demonstrate that increased TFEB expression plays a major role in regulating the reduction in cross-presentation observed upon BMDC maturation, and suggest that TFEB-mediated lysosomal activation plays a crucial role in determining the general capacity of APCs for cross-presentation (Supplemental Fig. 6).

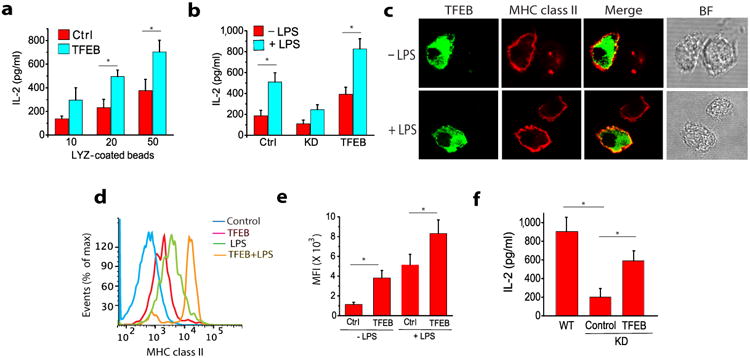

TFEB regulates MHC class II-restricted antigen presentation

Because lysosomal proteolysis plays a well-characterized role in MHC class II-restricted antigen processing and presentation 31 we asked if, in contrast to its role in inhibiting cross-presentation, the TFEB-mediated increase in lysosomal activity would enhance MHC class II antigen presentation in BMDCs. BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP or control-EGFP and TFEBKD BMDCs were incubated with varying concentration of hen egg lysozyme (HEL)-coated beads for six hours. Processing and presentation was assayed by measuring IL-2 production by the T cell hybridoma BO4, which is specific for HEL74-88 peptide in association with I-Ab. MHC class II-restricted presentation of HEL was significantly increased in TFEB-EGFP-transduced BMDCs compared to control-EGFP transduced BMDCs (Fig. 4a). Conversely, HEL presentation in TFEBKD BMDCs was significantly reduced compared to control cells (Fig. 4b), suggesting that the normal maturation-dependent increase in MHC class II antigen presentation was inhibited by TFEB silencing in BMDCs. In addition to its role in lysosomal degradation, TFEB is also involved in the fusion of lysosomes with the plasma membrane (lysosomal exocytosis) 32, a process known to be involved in the delivery of lysosomal MHC class II to the cell surface in response to LPS 33. Consistent with such a role, we observed that BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP had higher expression of MHC class II on their surface compared to non-transduced cells (Fig. 4c-e), while the up-regulation of MHC class II expression that is normally observed on BMDCs upon LPS-induced maturation 33 was further enhanced by TFEB-EGFP transduction (Fig. 4c-e). In addition, I-Ab-restricted HEL presentation was significantly reduced in TFEBKD macrophages compared to control cells (Fig. 4f), consistent with the dependence of steady-state lysosomal proteolytic activity on TFEB expression in these cells. Collectively, these data indicate that TFEB plays a critical role in regulating the processing of exogenous antigens by DCs and macrophages (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Figure 4. TFBE regulates MHC Class II antigen presentation in BMDCs.

(a) MHC class II mediated antigen presentation in TFEB-transduced BMDCs following exposure to HEL-coated beads. (b) The effect of TFEB silencing on the LPS-induced enhancement of MHC class II antigen presentation in BMDCs. (c) The effect of TFEB silencing on MHC class II antigen presentation of HEL by macrophages. (d-f) The role of TFEB in the translocation of MHC class II molecules (I-Ab) to the surface of BMDCs is evaluated by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry. For all panels unless otherwise indicated the data represents the mean ± SE from at least three independent experiments (cells isolated from at least three different mice), unless otherwise indicated. *P < 0.05 (Student's t-test).

TFEB modulates cross-presentation in vivo

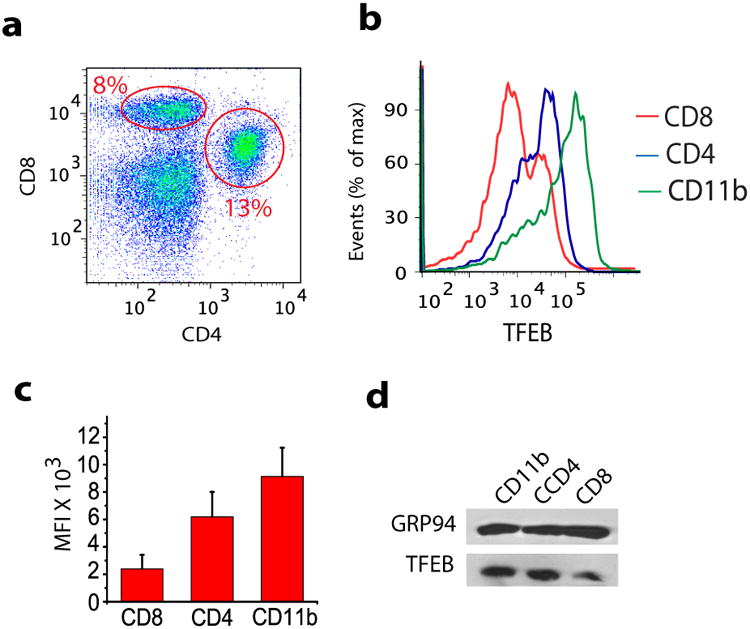

There are multiple DC subsets with different dedicated functions 34. It is not clear how these differences are established, but certain factors such as the cellular environment or maturation and activation state are most likely involved. In mice, lymphoid organ-resident CD8α+ DCs have been defined as the most efficient cross-presenting cells in vivo 35. Given that our experiments showed that TFEB negatively regulates cross-presentation, we hypothesized that splenic CD8+ DCs would have lower TFEB expression at steady-state compared to other APCs. By flow cytometry, CD11c+CD8+ cells comprised 8% of the total splenic DC population, while CD11c+CD4+ cells represented 13% (Fig. 5a). Consistent with our hypothesis, CD11c+CD8+ DCs in the spleen showed very low expression of TFEB compared to CD11c+CD4+ DCs, and splenic CD11b+ macrophages expressed more TFEB than CD11c+CD4+ DCs (Fig. 5b-d), which is likely to explain the high degradative capacity of macrophage lysosomes. Consistent with this suggestion, bone marrow-derived macrophages expressed much higher amounts of TFEB mRNA than bone marrow-derived DCs (Supplemental Fig. 5d). Altogether, our data suggest that the reduced expression of TFEB in CD8+ DCs is most likely a contributing factor in their superior cross-presentation capacity compared to macrophages and other DC subsets.

Figure 5. TFEB expression is reduced in cross-presenting CD8+ DCs.

(a) Freshly prepared splenocytes were labeled with CD11c-APC, CD4-FITC, and CD8-PE antibodies to identify splenic DCs subpopulations using flow cytometry. The figure showing the CD11c+ CD8 and CD4 DCs (b-d) TFEB expression in CD11b+ macrophages, CD11c+CD4+ DCs and CD11c+CD8+ DCs as revealed by flow cytometry (b-c) and western blot (d) analysis.

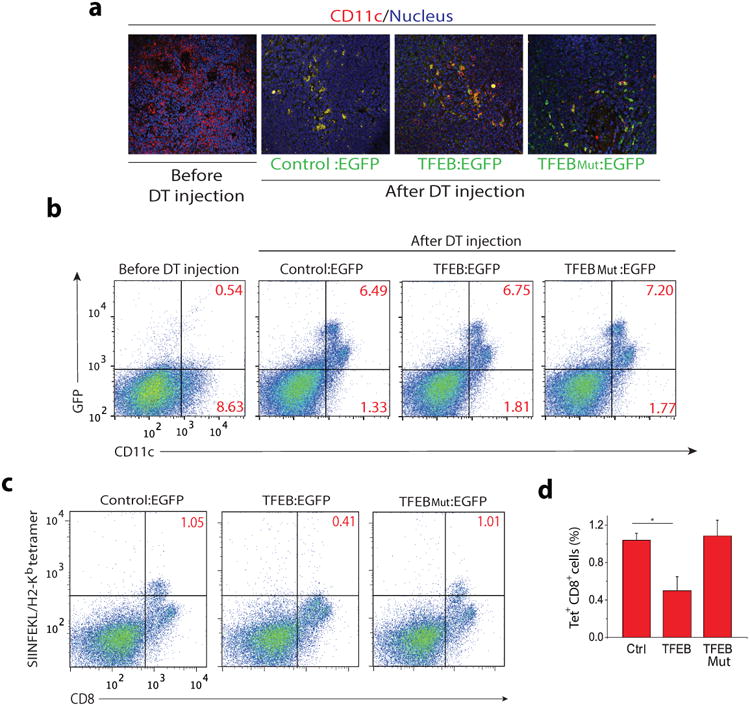

Cross-presentation is critical for the induction of an in vivo response by naïve CD8+ T cells, known as cross-priming. To determine if expression of TFEB by DCs plays a role in cross-priming, we used CD11c-DTR transgenic mice in which administration of diphtheria toxin (DT) ablates the CD11c+ population 36. BMDCs transduced with TFEB-EGFP or TFEBMut-EGFP were adoptively transferred into CD11c-DTR mice depleted of CD11c+ cells 24 hours after DT injection. To assay for cross-priming the mice were immunized the next day with soluble OVA, and endogenous CD11c+ DC numbers were maintained at low levels by a second DT injection on day 3 36. Five days after OVA immunization almost all splenic DCs were EGFP+ (donor derived), as assessed by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry (Fig. 6a-b). Priming of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells in these mice at day 5 was evaluated by flow cytometry using SIINFEKL/Kb tetramers. We observed a greater than two fold decrease in OVA-specific CD8+ T cells when the mice were reconstituted with DCs expressing TFEB-EGFP compared with mice reconstituted with DCs transduced with TFEBMut-EGFP or control-EGFP constructs (Fig 6c-d). These data indicate that TFEB expression decreases the ability of DCs to mediate CD8+ T cell cross-priming in vivo.

Figure 6. TFEB modulates cross-presentation in vivo.

CD11c/DTR transgenic mice were depleted of DCs by three injections of diphtheria toxin (DT) on days 1, 3, and 6 after receiving BMDCs transduced with EGFP alone, TFEB:EGFP or TFEBMut:EGFP. On day 2 the mice were immunized with OVA. Spleens were harvested on day 8 for analysis. (a,b) The majority of splenic CD11c+ cells of mice receiving transduced BMDCs were EGFP positive as shown by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry (c,d) OVA-specific priming of CD8+ T cells in the adoptively transferred mice was evaluated by SIINFEKL/Kb tetramer staining.

Discussion

Here we have established that the transcription factor TFEB plays a critical role in the regulation of antigen processing and presentation. In DCs, TFEB activation and nuclear translocation strongly down-regulated MHC class I-restricted antigen cross-presentation and cross-priming of naïve CD8+ T cells while up-regulating MHC class II antigen processing and presentation. We observed a role for TFEB in regulating the cross-presentation of two different antigens, the model antigen OVA associated with beads and necrotic HSV-1-infected HeLa cells, indicating that the functional modifications induced by its expression are not specific to a particular antigen. We suggest that TFEB acts as a molecular switch that regulates the favored mode of presentation of exogenous antigens, and the data strongly argue that this is a result of a TFEB-induced increase in lysosomal protease expression coupled with increased acidification. This unique function of TFEB most likely allows DCs to respond rapidly to environmental stimuli and appropriately regulate the dynamics of antigen presentation. Although the function of TFEB in vivo may be more relevant to DCs, silencing its expression in DCs and macrophages demonstrated that the two pathways are differentially regulated in these cell types.

In the mouse, cross-presentation in vivo is largely a property of the CD8α+ subclass of DCs and dermal migratory CD103+ DCs 3. Efficient cross-presentation has been correlated with a reduction in lysosomal and phagosomal proteolysis and maintenance of a high vacuolar pH relative to macrophages 28. Our data argue that for CD8α+ DCs reduced TFEB expression compared to macrophages and CD4+ DCs plays a major role in the maintenance of this subdued lysosomal phenotype. Maturation of DCs has variable effects depending on the stimulus and the DC subset under investigation 37. Upon phagocytosis, CD8α+ DCs maintain their high phagosomal pH by the Rac2-mediated recruitment of the NADPH oxidase Nox2 to the phagosome and the consequent alkalinization of the organelle by the reactive oxygen species (ROS) 25. Most likely this works in parallel with TFEB and this could potentially explain why we do not observe similar levels of acidification in DCs compared to macrophages when they are transduced with TFEB. Human tonsillar DCs were found to be competent for cross-presentation regardless of their surface phenotype 38, and it would be interesting to examine TFEB expression in these cell types.

The relative abilities of DCs to mediate cross-presentation or MHC class II presentation depend on their maturation state. Many stimuli can induce maturation, including microbial components, cytokines or even physical disruption in vitro or tissue damage in vivo 39. Our experiments suggest that in mouse bone marrow-derived DCs TFEB is rapidly activated and translocated to the nucleus upon treatment with LPS. The outcome of TFEB activation is a decrease in lysosomal pH and an increase in the expression of lysosomal proteases, indicating that TFEB controls a precise transcriptional program. Whether components of this program other than the regulation of protease expression and lysosomal acidification contribute to the differential effects on cross-presentation and MHC class II-restricted presentation remains to be determined. The upstream signaling factors and events leading to TFEB activation and expression are unknown but one potential mediator is protein kinase C (PKC). During osteoclast differentiation PKC-induced phosphorylation of the C-terminal region of TFEB has been shown to increase its activity 24. Certain isoforms of PKC have shown to be involved in LPS-mediated cell responses 40, 41, 42. In addition, PKC activation was previously shown to increase MHC class II antigen presentation by DCs 43, which we demonstrate is TFEB-dependent. TFEB is also regulated by mTORC1 in the context of nutritional stress 44, but currently there is no obvious connection between this and the TFEB-dependent effects we describe here.

TFEB may be involved in MHC class II antigen presentation pathways at multiple levels in addition to its role in increasing the degradative functions of lysosomes. It is up-regulated in response to a specific set of ligands involved in antibacterial responses (ligands for TLR2 and TLR4), but not antiviral responses (a ligand for TLR9), suggesting that TFEB expression may be particularly important for initiating CD4+ T cell responses to bacterial infection. However, TFEB also up-regulates autophagy-related genes 19 which are known to capture cytosolic antigens and deliver them to lysosomes for MHC class II antigen presentation, so a potential role in the antiviral CD4+ T cell response cannot be excluded 45. In addition to enhancing lysosomal acidification and protease expression, TFEB activation also induces the trafficking of MHC class II molecules to the cell surface. This could potentially be through the lysosomal calcium channel TRPML1, which is induced by TFEB and is involved in lysosomal exocytosis 46, 47 and trafficking of MHC class II molecules to the cell surface in macrophages 48. TFEB induction of lysosomal biogenesis in DCs may also result in more efficient and rapid phagolysosome generation and enhanced MHC class II-restricted processing of phagocytosed antigens.

Understanding how lysosomal activation regulates antigen presentation pathways may contribute to understanding how DCs might regulate both immunity and peripheral tolerance. Additionally, understanding what regulates the activation of lysosomal function in APCs will add considerably to our understanding of what initiates immune responses. Several studies have identified small molecules that activate TFEB in vitro 49. These molecules and any novel TFEB activators or inhibitors that may be generated could potentially regulate antigen presentation in the context of different diseases and provide opportunities for future drug development.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Animals were housed and used according to Yale's institutional guidelines. All animal work was conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines. Yale's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the use of mice in this study. All cell lines described were of mouse origin and have been previously published.

Peptides and reagents

The H2-Kb-binding SIINFEKL peptide from OVA257-264 was synthesized by the Keck Facility at Yale University. The MHC class II binding peptide HEL74-88 was synthesized by GeneScript. YM201636, LTA, and CpG were generous gifts from Dr. R. Medzhitov at the Yale School of Medicine. LPS (isolated from Escherichia coli) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ultrapure LPS and PGN were purchased from Invivogen.

Cells

Bone marrow-derived DCs were prepared from femurs/tibiae of mice between 6-12 weeks of age and cultured for 5-7 days with 2-3 medium replenishments without disturbing the cells. DCs were kept in RPMI 1640 (Sigma) with 10% FBS (Thermo, Fisher Scientific), 50 μM β-mercapthoethanol (Sigma) and 2mM L-glutamine, 100U/ml penicillin, 100mg/ml streptomycin (Pen/Strep), 12mM HEPES, non-essential amino acids (all GIBCO) and 20 ng/ml GM-CSF. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were prepared in the same fashion but incubated with RPMI-1640 containing M-CSF derived from L292 cells.

The B3Z CD8+ T cell hybridoma specific for OVA257-264-associated H2-Kb and the BO4 hybridoma specific for HEL74-88-associated I-Ab were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, Pen/Strep, 50μM 2-ME, 1mM pyruvate.

MHC class I-restricted T cells specific for the immunodominant peptide from HSV glycoprotein B (gB), gB498-505, were purified from spleens of gBT mice using mouse CD8a (Ly-2) MicroBeads from Miltenyi Biotec according to the manufacturer's protocol. Two rounds of isolation were performed and more than 80% of cells isolated were CD3 (T cell surface marker) positive as shown by FACS analysis.

HeLa, HEK 293T, and Vero cells were grown in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) with 10% FBS, GlutaMax (GIBCO) and 100U/ml penicillin, 100mg/ml streptomycin (Pen/Strep).

Maturation of DCs

DC maturation was induced on day 5 or day 6 of culture overnight or for shorter time as indicated in the figures. Maturation stimuli (LPS, ultrapure LPS, ultrapure PGN, ultrapure LTA or ultrapure CpG) were added to the medium without disturbing DC clusters. Immature control cells were left untreated.

Viral transduction

HEK 293T cells were transfected with 12μg of pCL-Eco and 12μg of TFEB:EGFP or TFEBMut:EGFP (All the basic residues (Arg245 to Arg248) within the predicted nuclear localization signal (NLS) of TFEB were mutated to alanine: TFEBR245–r248,AA) or EGFP empty vector (Control) and with 60μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) to produce retrovirus. After 4 hours incubation at 37°C the medium was changed to DC culture medium and the cells were shifted to 32°C. After 24 h filtered supernatant was added to day 1 bone marrow-derived DC cultures. The cells were spinfected at 32°C, at 2500 rpm for 90 minutes and then cultured at 37°C overnight. The next day, same process was repeated and cells were spinfected for the second time on day 2 of bone marrow derived DCs. On the day 3 fresh DC medium was added to the cells and they were cultures for 2 more days. This protocol usually resulted in 80%-85% transduction efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 1a). For viral transduction of shRNA, HEK 293T cells were transfected with TFEB specific shRNA construct, pCMV-VSVG (envelope plasmid), and psPAX2 (packaging plasmid) for producing viral particles.

HSV-1

HSV-1 stock was prepared by infecting 80–90% confluent monolayers of African green monkey kidney cells (Vero). Infected cells were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and were harvested after 3 days. Cells were collected and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 minutes to pellet cell debris. Clarified supernatant was collected and then filtered using a 0.45 um filter. The supernatant was then subjected to ultracentrifugation for 45 minutes at 14,000 rpm to pellet the virus. Pellets were re-suspended in complete medium and stored at 80°C until use.

Virus titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero monolayers. Briefly, 10-fold dilutions of virus were adsorbed onto Vero cells for 1 h at 37°C. The inoculum was then removed and fresh medium containing 0.4% agarose was added. Cells were fixed and stained with a 0.1% crystal violet solution after 2 days to determine the number of plaque

Preparation of infected cells

HeLa cells were infected with HSV-1 at a MOI of 5:1 for 1h in culture medium. Cells were then washed and kept in medium containing 0.2mM Acyclovir for overnight. Residual virus was UV inactivated. To produce necrotic bodies, HeLa-HSV were subjected to three rounds of freeze/thaw after residual virus inactivation and used without further incubation. Necrotic HeLa cells were re-suspended to 2.5×106/ml in DC medium. Plaque assays with both cell preparations confirmed that no infectious virus could be recovered. For direct infection of DCs, HSV was added at an MOI of 3 to DCs in medium containing 10μg/ml gentamicin instead of Pen/Strep. After 1h of incubation, DCs were washed three times and kept in Acyclovir-containing DC medium for 12h before addition of T cells as described below.

Antigen presentation assay

For OVA cross-presentation, OVA was non-covalently bound to 3μm latex beads (Polysciences). TFEB transduced or non-transduced DCs were harvested, washed, seeded at 5 × 105/24 well and pulsed for 6h with different ratios of OVA-beads or different concentrations of soluble OVA. During maturation experiments, 1μg/ml LPS was added the night before and during the bead pulse. DCs were then washed and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 10min. Fixation was stopped with 200mM glycine in PBS, pH 7.4. After 2 washes, DCs were co-cultured with 1×105 B3Z cells for 18h. For virus cross-presentation, inactivated or necrotic HSV-1 was directly added to immature DCs in medium containing 10μg/ml gentamicin instead of Pen/Strep. After 1h the DCs were washed three times and kept in DC medium for 12h before addition of CD8-positive T cells isolated from the spleen of gBT mice. For HEL stimulation, HEL was non-covalently bound to 3μm latex beads and the beads fed to the DCs as described for the OVA cross-presentation experiments and presentation assessed using BO4 hybridoma cells. For all assays, IL-2 in co-culture supernatants was measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD Biosciences).

Phagosomal Protein Degradation Assay

DCs were incubated with OVA coated latex beads for 15 minutes after which the un-ingested beads were removed and cells were incubated for indicated time points. Cells were disrupted in lysis buffer and centrifuged at 900 rpm for 4 min at 4°C. Supernatants containing the latex beads were collected and stained with a rabbit polyclonal anti-OVA antibody and FITC-coupled anti-rabbit antibodies in 96 well conic-bottom microplates. The amount of OVA protein remained on the surface of the beads was then analyzed by FACS.

Measurement of Phagosomal pH

OVA was conjugated with pHrodo succinimidyl ester (SE) red amine reactive dye or Alexa fluor 647 according to the manufactuer's instructions (Invitrogen), and 3μm latex beads were coated with OVA-SE (pH sensitive) and OVA-Alexa fluor conjugate (pH insensitive) overnight at 4°C. The next day, the beads were washed and stored in PBS. DCs were pulsed with the coupled beads for 20 min and then extensively washed in cold PBS. The cells were then incubated at 37°C for the indicated times and immediately analyzed by FACS. The ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) emission between the two dyes was determined. The MFI values were then compared with a standard curve obtained by resuspending the cells that had phagocytosed beads for 1 hour in solutions resembling intralysosomal ionic composition but of varying pH (ranging from pH 3-8) and containing 0.1% Triton X100. The cells were then analyzed by FACS to determine the emission ratio of the two fluorescent probes.

Flow cytometry

Staining for cell-surface markers was performed with the following mAbs and appropriate isotype controls (all BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C; anti-CD86, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD11c, anti-CD11b, anti-CD19. Anti I-Ab mAb was obtained from Affymetrix. H-2Kb – associated with the OVA SIINFEKL peptide was detected with the mAb 25.D1. TFEB was detected in fixed and permeablized cells with anti-TFEB antibody from MyBioSource, Data was collected on BD Accuri flow cytometer system (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software.

DC depletion and adoptive transfers

CD11c/DTR mice were injected on day 1 with 10ng DT per gram of body weight suspended in PBS. Twenty four hours later, mice were injected i.v. with 1 × 106 bone marrow-derived DCs transduced with control:EGFP, TFEB:EGRP, or TFEBMut:EGFP vectors. The next day mice were immunized by injection of 200μg of OVA protein adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. Five days after OVA immunization spleens from each mouse was harvested and single cell suspension was obtained. In order to ensure low levels of endogenous CD11c+ cell throughout the experiment, every three days mice were injected with a low dose of DT (4ng/g of body weight) suspended in PBS. In vivo priming was evaluated by staining the splenocytes with PE-conjugated SIINFEKL/Kb tetramer and CD8β-FITC antibody for one hour on ice. The percentage of SIINFEKL/Kb positive/ CD8+ cells were identified by flow cytometry.

Fluorescence staining, confocal microscopy and immunohistochemistry

Surface staining was performed on non-permeablized DCs with anti-H-2Kb and anti-I-Ab mAbs at a 1:100 dilution for 2 hours at 4°C to detect the translocation of the class I and class II molecules to the cell surface. Cells were washed, fixed with 1% PFA and then processed for microscopy. Lamp-1 staining was performed on fixed and permeabilized DCs by using anti-Lamp-1 (1D4B, Iowa hybridoma bank). All samples analyzed using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5 μm slice sections prepared from paraffin-embedded spleen tissues using microtome.

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAase MiniKit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First strand cDNA was synthesized using AffinityScript Multi Temperature cDNA synthesis kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacture's protocol. Quantitative PCR analysis was performed using SYBER Select Master Mix (Invitrogen) to detect the expression of the differet genes using the forward and reverse primers as indicated in the supplemental table 1.

Phagocytosis assay

2.5×106 DC/ml were incubated with 3μm beads coated with OVA conjugated to Alexa fluor 647 at a 5:1 ratio for 1h at 37°C. Samples were then pelleted at 1200rpm for 5 minutes and washed twice with cold PBS. Samples were then resuspended in FACS buffer and transferred to a V bottom shaped 96 well plate. After Fc-receptors were blocked (Mouse BD Fc Block), extracellular beads were stained with rabbit anti-OVA antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit F(ab')2, and then fixed in 2% PFA-PBS. The amount of particle uptake was assessed by FACS by gating on DCs. In a parallel experiment, the DCs were incubated with cytochalasin D (CytoD) for 15 minutes and maintained in CytoD to inhibit phagocytosis.

Silencing TFEB

TFEB specific shRNA (Sequence: CCGGCCAAGAAGGATCTGGACTTAACTCGAGTTAAGTCCAGATCCTTCTTGGTTTTTG, Clone ID:NM_011549.2-1526s1c1, TRCN0000085549) specifically designed for Lentiviral delivery was purchased from Sigma (Mission shRNA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and National Institutes of Health grant RO1-AI097206 to PC, and by National Institute of Health, National Research Service Award (T32 HL007974) to MS. We are grateful to Dr. S. Ferguson for the TFEB-EGFP and TFEBMut-EGFP constructs, Dr. A. Iwasaki for the gBT and CD11c-DTR Tg mice, Dr. W. Shlomchik for SIINFEKL/Kb tetramers, Dr. R. Medzhitov for sharing reagents. We are also thankful to Drs. R. Leonhadt and J. Grotzke for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We appreciate the encouragement and helpful comments of the members of the Cresswell laboratory.

References

- 1.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106(3):255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum JS, Wearsch PA, Cresswell P. Pathways of antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:443–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joffre OP, Segura E, Savina A, Amigorena S. Cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(8):557–569. doi: 10.1038/nri3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):265–277. doi: 10.1038/nrc3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira OV, Botelho RJ, Grinstein S. Phagosome maturation: aging gracefully. Biochem J. 2002;366(Pt 3):689–704. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accapezzato D, Visco V, Francavilla V, Molette C, Donato T, Paroli M, et al. Chloroquine enhances human CD8+ T cell responses against soluble antigens in vivo. J Exp Med. 2005;202(6):817–828. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson NS, Villadangos JA. Regulation of antigen presentation and cross-presentation in the dendritic cell network: facts, hypothesis, and immunological implications. Adv Immunol. 2005;86:241–305. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackerman AL, Kyritsis C, Tampe R, Cresswell P. Early phagosomes in dendritic cells form a cellular compartment sufficient for cross presentation of exogenous antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(22):12889–12894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Rock KL. A phagosome-to-cytosol pathway for exogenous antigens presented on MHC class I molecules. Science. 1995;267(5195):243–246. doi: 10.1126/science.7809629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guermonprez P, Saveanu L, Kleijmeer M, Davoust J, Van Endert P, Amigorena S. ER-phagosome fusion defines an MHC class I cross-presentation compartment in dendritic cells. Nature. 2003;425(6956):397–402. doi: 10.1038/nature01911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houde M, Bertholet S, Gagnon E, Brunet S, Goyette G, Laplante A, et al. Phagosomes are competent organelles for antigen cross-presentation. Nature. 2003;425(6956):402–406. doi: 10.1038/nature01912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cresswell P, Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Peaper DR, Wearsch PA. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch J, Tampe R. The macromolecular peptide-loading complex in MHC class I-dependent antigen presentation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63(6):653–662. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5462-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trombetta ES, Ebersold M, Garrett W, Pypaert M, Mellman I. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science. 2003;299(5611):1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delamarre L, Pack M, Chang H, Mellman I, Trombetta ES. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science. 2005;307(5715):1630–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1108003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delamarre L, Holcombe H, Mellman I. Presentation of exogenous antigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II molecules is differentially regulated during dendritic cell maturation. J Exp Med. 2003;198(1):111–122. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin ML, Zhan Y, Villadangos JA, Lew AM. The cell biology of cross-presentation and the role of dendritic cell subsets. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86(4):353–362. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. 2009;325(5939):473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Settembre C, Fraldi A, Medina DL, Ballabio A. Signals from the lysosome: a control centre for cellular clearance and energy metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(5):283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visvikis O, Ihuegbu N, Labed SA, Luhachack LG, Alves AM, Wollenberg AC, et al. Innate host defense requires TFEB-mediated transcription of cytoprotective and antimicrobial genes. Immunity. 2014;40(6):896–909. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porgador A, Yewdell JW, Deng Y, Bennink JR, Germain RN. Localization, quantitation, and in situ detection of specific peptide-MHC class I complexes using a monoclonal antibody. Immunity. 1997;6(6):715–726. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roczniak-Ferguson A, Petit CS, Froehlich F, Qian S, Ky J, Angarola B, et al. The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci Signal. 2012;5(228):ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stock AT, Mueller SN, Kleinert LM, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Jones CM. Optimization of TCR transgenic T cells for in vivo tracking of immune responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85(5):394–396. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferron M, Settembre C, Shimazu J, Lacombe J, Kato S, Rawlings DJ, et al. A RANKL-PKCbeta-TFEB signaling cascade is necessary for lysosomal biogenesis in osteoclasts. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):955–969. doi: 10.1101/gad.213827.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savina A, Jancic C, Hugues S, Guermonprez P, Vargas P, Moura IC, et al. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2006;126(1):205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Settembre C, De Cegli R, Mansueto G, Saha PK, Vetrini F, Visvikis O, et al. TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation-induced autoregulatory loop. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(6):647–658. doi: 10.1038/ncb2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ackerman AL, Cresswell P. Cellular mechanisms governing cross-presentation of exogenous antigens. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(7):678–684. doi: 10.1038/ni1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner CS, Grotzke JE, Cresswell P. Intracellular events regulating cross-presentation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:138. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gil-Torregrosa BC, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Kessler B, Guermonprez P, Ploegh HL, Fruci D, et al. Control of cross-presentation during dendritic cell maturation. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(2):398–407. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida K, Unuma K, Funakoshi T, Aki T, Uemura K. Activation of Master Autophagy Regulator TFEB During Systemic LPS Administration in the Cornea. J Toxicol Pathol. 2014;27(2):153–158. doi: 10.1293/tox.2014-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geuze HJ. The role of endosomes and lysosomes in MHC class II functioning. Immunol Today. 1998;19(6):282–287. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina DL, Fraldi A, Bouche V, Annunziata F, Mansueto G, Spampanato C, et al. Transcriptional activation of lysosomal exocytosis promotes cellular clearance. Dev Cell. 2011;21(3):421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow A, Toomre D, Garrett W, Mellman I. Dendritic cell maturation triggers retrograde MHC class II transport from lysosomes to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2002;418(6901):988–994. doi: 10.1038/nature01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(3):151–161. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shortman K, Heath WR. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset. Immunol Rev. 2010;234(1):18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung S, Unutmaz D, Wong P, Sano G, De los Santos K, Sparwasser T, et al. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8+ T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17(2):211–220. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mildner A, Jung S. Development and function of dendritic cell subsets. Immunity. 2014;40(5):642–656. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Segura E, Durand M, Amigorena S. Similar antigen cross-presentation capacity and phagocytic functions in all freshly isolated human lymphoid organ-resident dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;210(5):1035–1047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joffre O, Nolte MA, Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227(1):234–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asehnoune K, Strassheim D, Mitra S, Yeol Kim J, Abraham E. Involvement of PKCalpha/beta in TLR4 and TLR2 dependent activation of NF-kappaB. Cell Signal. 2005;17(3):385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGettrick AF, Brint EK, Palsson-McDermott EM, Rowe DC, Golenbock DT, Gay NJ, et al. Trif-related adapter molecule is phosphorylated by PKC{epsilon} during Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600462103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou X, Yang W, Li J. Ca2+- and protein kinase C-dependent signaling pathway for nuclear factor-kappaB activation, inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated rat peritoneal macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(42):31337–31347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Majewski M, Bose TO, Sille FC, Pollington AM, Fiebiger E, Boes M. Protein kinase C delta stimulates antigen presentation by Class II MHC in murine dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19(6):719–732. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Settembre C, Zoncu R, Medina DL, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Huynh T, et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 2012;31(5):1095–1108. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dengjel J, Schoor O, Fischer R, Reich M, Kraus M, Muller M, et al. Autophagy promotes MHC class II presentation of peptides from intracellular source proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(22):7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501190102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samie M, Wang X, Zhang X, Goschka A, Li X, Cheng X, et al. A TRP channel in the lysosome regulates large particle phagocytosis via focal exocytosis. Dev Cell. 2013;26(5):511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samie MA, Xu H. Lysosomal exocytosis and lipid storage disorders. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(6):995–1009. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R046896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson EG, Schaheen L, Dang H, Fares H. Lysosomal trafficking functions of mucolipin-1 in murine macrophages. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song W, Wang F, Lotfi P, Sardiello M, Segatori L. 2-Hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin promotes transcription factor EB-mediated activation of autophagy: implications for therapy. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(14):10211–10222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.506246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.