Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess patient and physician perceptions of heart failure (HF) disease severity and treatment options.

Background

The prognosis for ambulatory patients with advanced HF on medical therapy is uncertain, yet has important implications for decision making regarding transplantation and left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement.

Methods

Ambulatory patients with advanced HF (NYHA class III–IV, INTERMACS profiles 4–7) on optimized medical therapy were enrolled across 11 centers. At baseline, treating cardiologists rated patients for perceived risk for transplant, LVAD, or death in the upcoming year. Patients were also surveyed about their own perceptions of life expectancy and willingness to undergo various interventions.

Results

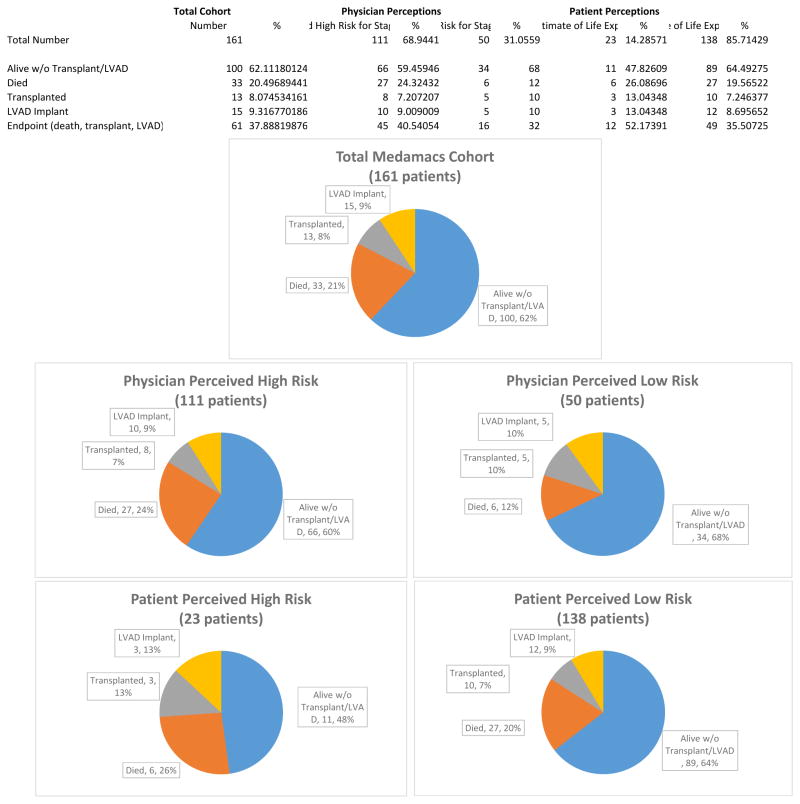

At enrollment, physicians regarded 111 (69%) of the total cohort of 161 patients to be at high risk for transplant, LVAD, or death, while only 23 patients (14%) of patients felt they were at high risk. After a mean follow-up of 13 months, 61 (38%) patients experienced an endpoint with 33 (21%) deaths, 13 (8%) transplants, and 15 (9%) LVAD implants. There was poor discrimination between risk prediction among both patients and physicians. Among physician-identified high risk patients, 77% of patients described willingness to consider LVAD, but 63% indicated that they would decline one or more other simpler forms of life-sustaining therapy such as ventilation, dialysis, or a feeding tube.

Conclusions

Among patients with advanced HF, physicians identified the majority to be at high risk for transplant, LVAD, or death while few patients recognized themselves to be at high risk. Patients expressed inconsistent attitudes toward lifesaving treatments, possibly indicating poor understanding of these therapies. Educational interventions regarding disease severity and treatment options should be introduced prior to the need for advanced therapies such as intravenous inotropic therapy, transplantation, or LVAD.

Keywords: mechanical circulatory support, ventricular assist device, cardiac transplantation, advanced heart failure, patient decision making

Introduction

The risk and benefits for left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy in patients with cardiogenic shock or inotrope dependent advanced heart failure (HF)—Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) patient profiles 1–3—have been well studied. However, the prognosis for ambulatory patients on oral medical therapy for advanced HF (INTERMACS profiles 4–7) is less well understood by patients and by their physicians. Patient-centered care for patients with advanced HF requires that patients understand possible outcomes and learn about potential treatment options including LVAD surgery which can improve quality of life and functional capacity for patients limited by HF symptoms, even when death is not imminent.1,2 However, patients may not full appreciate the invasive procedures that may be required for support during the post-operative period.

We hypothesized that there may be differences in patient perceptions of their HF disease severity compared to physician perceptions of HF severity. Broader understanding of these differences may help facilitate better patient-physician communication regarding the advanced HF therapies of transplant and LVAD. The aim of this study was to determine if there are differences between physician and patient perceptions of disease severity and likelihood of requiring stage D interventions in INTERMACS 4–7 patients with advanced HF. A secondary aim was to assess patient willingness to consider advanced HF treatment options in the context of other life sustaining therapies.

Methods

Patient Selection

Ambulatory patients with advanced HF (New York Heart Association class III–IV, INTERMACS profiles 4–7) were enrolled in the prospective, observational Medical Arm for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (MedaMACS) Registry across 11 advanced HF-transplant cardiology centers from May 17, 2013 to October 31, 2015. The overall goal of this registry was to better characterize and define the prognosis of outpatients with chronic advanced HF on oral (and not intravenous) medical therapy. Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published but generally included patients with chronic advanced HF (diagnosis for at least 1 year and on evidence-based medications for at least 3 months unless documented contraindication or intolerance), at least one prior HF hospitalization in the preceding year, and at least one other high risk feature including (1) another HF related hospitalization, (2) high natriuretic peptide level, (3) poor functional status as assessed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing or 6-minute walk, or (4) a high risk Seattle HF model score.3 The key exclusion criteria included current intravenous inotrope therapy, active listing for heart transplant, a congenital heart defect, a diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis, or a non-cardiac diagnosis anticipated to limit survival or functional status. All participating institutions were required to comply with local regularity and privacy guidelines and to submit the MedaMACS protocol for review and approval by their institutional review boards. Of note, this MedaMACS Registry study is a larger and distinct study that followed the initial screening pilot MedaMACS feasibility study that enrolled patients in a smaller group of centers between October 2010 and April 2011.4,5

Categorization of Physician and Patient Perceptions of Heart Failure Risk

At the time of enrollment, the treating HF clinicians and enrolled patients were asked about their perceptions of HF prognosis. Specifically, physicians were asked for their best estimate of the likelihood that the patient would become sick enough to warrant urgent Stage D intervention within one year (including home intravenous inotropic therapy, hospice, VAD, and/or urgent transplant). The response choices included: Highly Likely, Moderately Likely, Uncertain, Moderately Unlikely, and Highly Unlikely. Respondents were meant to use subjective judgment to discern among these choices and only one selection was allowed for each study participant. The physician responses were categorized into two groups: Physician Perceived High Risk (if Highly Likely or Moderately Likely was selected) and Physician Perceived Low Risk (if Uncertain, Moderately Unlikely, or Highly Unlikely was selected).

Similarly, patients with HF were asked to estimate how much longer they estimated they would live based on how they felt at the time of enrollment. Patient responses were categorized into two groups: Patient Perceived High Risk (those who estimated a life expectancy of less than 1 year) and Patient Perceived Low Risk (those who estimated a life expectancy of greater than 1 year). Respondents were meant to use subjective judgment to discern among the categories and only one selection was allowed for each study participant.

Outcome Measures

Data were originally to be collected prospectively for patients over a pre-specified 24 month follow up period. However due to loss of funding for ongoing data collection, this report is an analysis of all available data after a mean follow up of 13±9 months. In addition to the baseline physician and patient questionnaires regarding HF prognosis, demographics, clinical characteristics, laboratory, echocardiography, hemodynamic, and functional status data were collected at enrollment. The outcomes of interest in this study were a Stage D HF endpoint, which included death, transplant, or LVAD placement. These measures were reassessed in addition to collection of interval events at 1 month, 1 year, and 2 years after entry into the study. Additional phone calls to measure interval events were made at 6 and 18 month time intervals.

Patient Perceptions of Life Sustaining Therapies

At enrollment patients were asked to complete a questionnaire about their opinions about LVAD therapy and willingness to undergo a variety of common life-sustaining therapies. The patients did not receive any additional education or supplementary materials about LVAD or life-sustaining therapies as the goal of this analysis was to discern what happens in real-world clinical care. These survey responses were analyzed among the Physician Perceived High Risk cohort as this is the group of patients were discussions regarding the advanced HF treatment options of transplant and LVAD and other life sustaining therapies have usually started. In addition, HF patients who would want or consider a LVAD were queried about their willingness to undergo additional more common life-sustaining therapies including chest compressions, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, transfer to an intensive care unit, or a feeding tube.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were preformed centrally at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Data and Clinical Coordinating Center. Numerical data were reported as mean values ± standard deviations or count (percentage). Univariate comparisons between the cohorts of patients based on differing perceptions of HF risk were performed using the chi-square test of Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the one-way ANOVA test for continuous variables. A generalized linear model was utilized to assess for interactions between Physician and Patient perceptions of High versus Low risk. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log rank tests were used to demonstrate unadjusted survival differences among the various cohort of patients. Patient opinions about LVAD and life-sustaining therapy survey data were reported as a percentage for qualitative descriptive analysis. SAS 9.4 statistical software (Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 161 patients were enrolled between May 17, 2013 and October 31, 2015. Physicians identified 111 patients (69%) of this cohort as being High Risk for urgent transplant, LVAD, or death within the year after enrollment and 50 (31%) patients as being Low Risk. By contrast, patients’ estimation of life expectancy were not in line with physicians’ estimate of prognosis. Of the total cohort of 161 patients, 138 (86%) patients thought they would live longer than 1 year while only 23 (14%) patients thought they would live less than 1 year.

Among the overall cohort, the majority of patients were INTERMACS profiles 5–6 and had similar demographic characteristics. Compared to Physician Perceived Low Risk patients, the Physician Perceived High Risk patients were older, had lower INTERMACS profiles, were followed by the treating program for a shorter length of time, were less likely to be on an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker, had worse renal function, higher natriuretic peptide levels, and higher pulmonary artery pressures (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, compared to Patient Perceived Low Risk patients, the Patient Perceived High Risk cohort had greater warfarin utilization, lower blood pressure, and lower cardiac output (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Enrollment

| Physician Perceived High Risk (N=111) | Physician Perceived Low Risk (N=50) | Patient Perceived High Risk (N=23) | Patient Perceived Low Risk (N=138) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 60 ± 11 | 56 ± 10* | 63 ± 10 | 58 ± 11 |

| Male gender | 68% | 62% | 70% | 66% |

| Race | ||||

| African-American | 27% | 36% | 13% | 33% |

| Caucasian | 72% | 60% | 87% | 65% |

| Other | 1% | 4% | 0% | 2% |

| Married or domestic partnership | 58% | 63% | 61% | 60% |

| Post high school education | 10% | 13% | 7% | 12% |

| Heart Failure Characteristics | ||||

| Etiology of heart failure | ||||

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 41% | 34% | 39% | 38% |

| Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy | 35% | 48% | 35% | 40% |

| Other etiology | 24% | 18% | 26% | 22% |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator Present | 87% | 78% | 91% | 83% |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy Present | 35% | 21% | 43% | 29% |

| INTERMACS Patient Profile | ||||

| 4-Resting Symptoms | 17 (15%) | 4 (8%)* | 6 (26%) | 15 (11%) |

| 5-Exertion Intolerant | 40 (36%) | 8 (16%)* | 9 (39%) | 39 (28%) |

| 6-Exertion Limited | 48 (43%) | 28 (56%)* | 6 (26%) | 70 (51%) |

| 7-Advanced NYHA Class 3 | 6 (5%) | 9 (18%)* | 2 (9%) | 13 (10%) |

| Inotrope therapy required in preceding 6 months | 19% | 17% | 30% | 16% |

| Number of cardiac hospitalizations in preceding 12 months | ||||

| One | 32 (29%) | 14 (28%) | 5 (21%) | 41(30%) |

| Two | 40 (36%) | 21 (42%) | 8 (35%) | 53 (39%) |

| Three | 15 (13%) | 11 (22%) | 2 (9%) | 24 (17%) |

| Four or more | 24 (22%) | 3 (6%) | 8 (35%) | 19 (14%) |

| Prior transplant and/or DT-LVAD Evaluation | 23% | 26% | 22% | 24% |

| Reason for initial referral to advanced HF program | ||||

| Cardiac transplant and/or DT-LVAD Evaluation | 48 (43%) | 12 (24%) | 12 (52%) | 48 (35%) |

| Evaluation of severe heart failure | 45 (41%) | 20 (40%) | 8 (35%) | 57 (41%) |

| New diagnosis heart failure within same institution | 6 (5%) | 8 (16%) | 1 (4%) | 13 (9%) |

| Unknown | 12 (11%) | 10 (20%) | 2 (9%) | 20 (15%) |

| Length of Time followed by program | ||||

| <3 months | 34 (31%) | 9 (18%)* | 12 (52%) | 31 (22%) |

| 3–12 months | 20 (18%) | 8 (16%)* | 1 (4%) | 27 (20%) |

| 1–2 years | 19 (17%) | 6 (12%)* | 3 (13%) | 22 (16%) |

| >2 years | 38 (34%) | 27 (54%)* | 7 (31%) | 58 (42%) |

| Medication usage at the time of enrollment | ||||

| ACEI or ARB | 52% | 76%* | 48% | 62% |

| Beta-blockers | 87% | 96% | 78% | 92% |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 63% | 66% | 57% | 65% |

| Loop diuretics | 93% | 92% | 95% | 92% |

| Digoxin | 47% | 53% | 45% | 50% |

| Hydralazine | 33% | 27% | 43% | 29% |

| Nitrate | 36% | 35% | 38% | 35% |

| Warfarin | 45% | 44% | 68% | 41%† |

| Aspirin | 64% | 60% | 65% | 62% |

| Statin | 55% | 53% | 61% | 54% |

P<0.05 for comparison of Physician Perceived High vs. Low Risk

P<0.05 for comparison of Patient Perceived High vs. Low Risk

P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics at Enrollment

| Physician Perceived High Risk (N=111) | Physician Perceived Low Risk (N=50) | Patient Perceived High Risk (N=23) | Patient Perceived Low Risk (N=138) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vital Signs | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 93 ± 26 | 90 ± 24 | 92 ± 29 | 92 ± 25 |

| Height (cm) | 173 ± 10 | 171 ± 10 | 175 ± 10 | 172 ± 10 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 31 ± 8 | 31 ± 9 | 29 ± 8 | 31 ± 8 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 80 ± 15 | 79 ± 14 | 79 ± 13 | 80 ± 15 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 109 ± 67 | 114 ± 19* | 104 ± 14 | 112 ± 15† |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 67 ± 10 | 70 ± 11 | 63 ± 8 | 69 ± 11† |

| Laboratory Values | ||||

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137 ± 4 | 137 ± 4 | 136 ± 4 | 138 ± 4 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.5 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 38 ± 22 | 28 ± 13* | 39 ± 24 | 34 ± 19 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.5* | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (u/L) | 30 ± 32 | 43 ± 60 | 31 ± 23 | 35 ± 45 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (u/L) | 30 ± 14 | 38 ± 37 | 32 ± 13 | 33 ± 25 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.8 |

| NT-pro B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/ml) | 6225±5408 | 2903±2820* | 6181±4462 | 5289±5150 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.6 |

| Pre-albumin (mg/dL) | 20 ± 7 | 24 ± 9 | 18 ± 7 | 21 ± 7 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 127 ± 42 | 140 ± 44 | 107 ± 15 | 135 ± 45 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 10 ± 6 | 8 ± 3 | 9 ± 3 | 10 ± 6 |

| White blood cell count (K/uL) | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 | 13 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 38 ± 6 | 40 ± 6 | 39 ± 8 | 39 ± 6 |

| Platelets (K/uL) | 220 ± 78 | 207 ± 66 | 201 ± 75 | 218 ± 75 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 2.3 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 1.6 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 20 ± 8 | 25 ± 10* | 19 ± 9 | 22 ± 9 |

| Baseline Exercise Testing and Functional Status | ||||

| Six Minute Walk (meters) | 207 ± 149 | 173 ± 171 | 180 ± 168 | 199 ± 155 |

| Gait speed (meters/second) | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5* | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.4 |

| Peak oxygen uptake VO2 (mL/kg/min) | 11.6 ± 3.4 | 13.4 ± 7.0* | 10.1 ± 1.6 | 12.2 ± 4.7 |

| Peak oxygen uptake (%) predicted | 43 ± 12 | 40 ± 18 | 29 ± 11 | 43 ± 13 |

| Ventilatory efficiency (VE/VCO2) | 37 ± 11 | 35 ± 8 | 34 ± 1 | 36 ± 11 |

| Peak respiratory exchange ratio | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Echocardiographic and Right Heart Catheterization Hemodynamic Data | ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 21 ± 6 | 22 ± 7 | 21 ± 7 | 21 ± 7 |

| LV dimension diastole (cm) | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 6.5 ± 0.9 |

| Right atrial pressure (mmHg) | 12 ± 6 | 11 ± 6 | 14 ± 6 | 11 ± 6 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mmHg) | 53 ± 13 | 47 ± 14* | 56 ± 13 | 51 ± 13 |

| Pulmonary artery diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 26 ± 7 | 22 ± 9* | 27 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 |

| Pulmonary wedge pressure (mmHg) | 22 ± 8 | 19 ± 9 | 23 ± 9 | 21 ± 8 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | 3.8 ± 1.8 | 4.6 ± 1.3† |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.7† |

P<0.05 for comparison of Physician Perceived High vs. Low Risk

P<0.05 for comparison of Patient Perceived High vs. Low Risk

P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The overall number of study endpoints among the entire study population was high after a mean follow up of 13 ± 9 months. Of 161 total patients, 100 (62%) patients were alive without a transplant or LVAD while 61 (38%) patients experienced an endpoint with 33 (21%) deaths, 13 (8%) patients receiving a transplant, and 15 (9%) patients undergoing LVAD implantation. This overall high number of endpoints was high regardless of physician or patient perceived risk (Figure 1). Specifically, among the 111 Physician Perceived High Risk patients, 45 (40%) patients experienced an endpoint with 27 (24%) deaths, 8 (7%) transplants, and 10 (9%) LVADs (Table 3). These rates are very similar to the Patient Perceived Low Risk cohort, where of the 138 patients who estimated their life expectancy to be >1 year, 49 (36%) patients experienced an endpoint with 27 (20%) deaths, 10 (7%) transplants, and 12 (9%) LVADs (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Interim events after a mean follow up of 13±9 months among MedaMACS patients stratified by physician and patient perceptions of risk for progression of heart failure.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes based on physician and patient perceived risk for poor outcome within one year of enrollment

| Physician Perceived High Risk (N=111) | Physician Perceived Low Risk (N=50) | Patient Perceived High Risk (N=23) | Patient Perceived Low Risk (N=138) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Outcomes | ||||

| Survival Outcomes | ||||

| Mortality | 27 (24%) | 6 (12%) | 6 (26%) | 27 (20%) |

| Ventricular assist device received | 10 (9%) | 5 (10%) | 3 (13%) | 12 (9%) |

| Transplant received | 8 (7%) | 5 (10%) | 3 (13%) | 10 (7%) |

| Alive without LVAD or Transplant | 66 (60%) | 34 (68%) | 11 (48%) | 89 (64%) |

| Inotropes required | 13 (12%) | 6 (12%) | 3 (13%) | 16 (12%) |

| At least one rehospitalization | 41 (37%) | 12 (24%) | 9 (39%) | 44 (32%) |

| Total Number of Rehospitalizations | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.3 ± 2.2 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 2.0 |

Although physicians were more likely to flag patients as high risk than the patients themselves, there were no statistically significant differences in survival or surgical HF therapies between Physician Perceived High Risk vs. Low Risk and Patient Perceived High Risk vs. Low Risk cohorts. Risk perception also did not track with rehospitalization frequency.

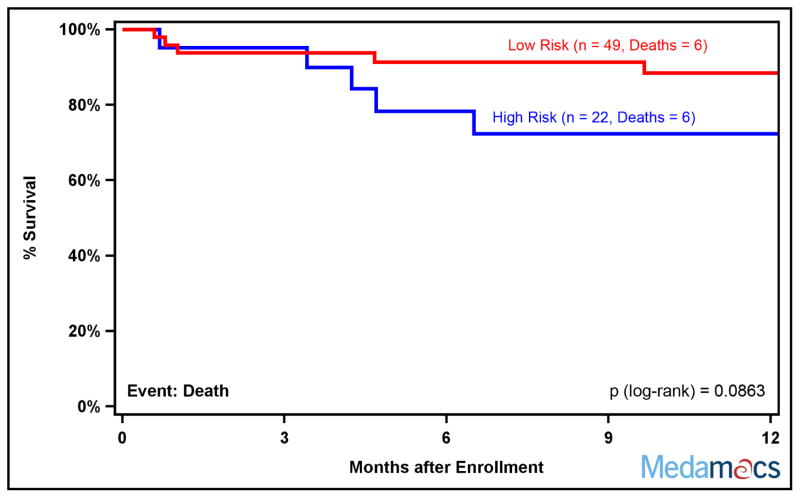

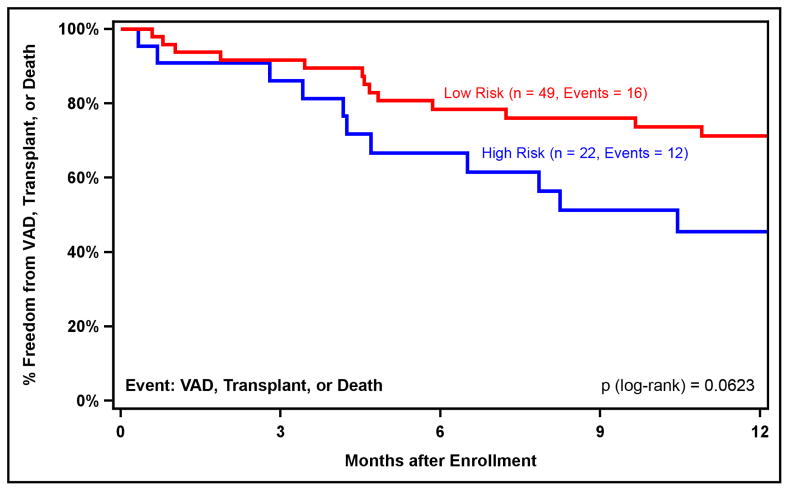

Physicians’ and Patients’ perceptions of risk were combined into a Combined High Risk cohort (including patients that Physicians and Patients both perceived as high risk, 22 patients) and a Combined Low Risk cohort (including patients that Physicians and Patients both perceived as low risk, 49 patients), to determine if there were differences in prognosis among these cohorts. There was a suggestion that the Combined High Risk cohort appeared to have higher all-cause mortality rates (Figure 2) as well as lower survival free of death, transplant, or LVAD (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Survival by Initial Perceptions of Heart Failure Prognosis. The High Risk cohort included patients that physicians and patients both perceived as high risk while the Low Risk cohort included patients that physicians and patients both perceived as low risk. Patients were censored at time of transplant or ventricular assist device placement.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Freedom from VAD, Transplant, or Death by Initial Perceptions of Heart Failure Prognosis. The High Risk cohort included patients that physicians and patients both perceived as high risk while the Low Risk cohort included patients that physicians and patients both perceived as low risk.

Patient Opinions about LVAD and Life-Sustaining Therapies Survey Data

Among the Physician Perceived High Risk cohort, patients’ perceptions of their own life expectancy were incongruent with their physicians perceptions as 22 (21%) patients estimated a life expectancy of less than 1 year, 23 (22%) patients estimated a life expectancy of 2–5 years, and 45 (42%) patients estimated a life expectancy of >5 years (Table 4). Furthermore, only 51% had a designated health care proxy or power of attorney and only 37% had discussed treatment options regarding life-sustaining therapies with their physicians. Opinions on specific treatments were also inconsistent as 77% of patients responded that they would consider LVAD implantation, yet many among this group would have declined other more simple forms of life-sustaining therapy. For example, of the patients willing to consider LVAD implantation, 52% declined ventilation, 46% declined dialysis, and 63% declined a feeding tube (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient opinions regarding LVAD and life-sustaining therapies survey results among Physician Perceived High Risk patients

| Patient Survey Question at Time of Enrollment | Affirmative Response Among Physician-Identified High Risk Patients |

|---|---|

| What is your best estimate of how much longer you have to live? | |

| Less than 1 year | 21% |

| Between 2 and 5 years | 22% |

| More than 5 years | 42% |

| Don’t know | 15% |

| I have a designated health care proxy or power of attorney. | 51% |

| I have talked to my physician about life-sustaining therapies. | 37% |

| How would you feel about having a LVAD placed? | |

| I would want or consider a LVAD. | 77% |

| I would refuse a LVAD. | 23% |

| Opinions about Life-Sustaining Therapies Among Patients Who Would Consider a LVAD | |

| I would want any and all life-sustaining therapies available. | 54% |

| I would NOT want the following life-sustaining therapies: | |

| Do not want: Chest compressions | 33% |

| Do not want: Breathing machine | 52% |

| Do not want: Kidney dialysis | 46% |

| Do not want: Transfer to intensive care unit | 15% |

| Do not want: Feeding tube if unable to eat | 63% |

Discussion

Among ambulatory patients with advanced HF on oral medical therapy who were hospitalized within the previous year, the risk of progression to stage D therapies is high, regardless of whether the treating HF physicians or patients themselves identified high risk. More importantly, there was a discrepancy between patients and physicians among this group of INTERMACS 4–7 patients, where the physicians felt that over two thirds of these patients were at high risk for stage D intervention in the upcoming year. Despite receiving care at predominantly referral-based advanced HF-transplant cardiology centers, only 14% of these same patients felt they were at high risk. These data are consistent with other reports suggesting patients with HF often tend to underestimate the severity of their disease process and overestimate their own prognosis.6 Discordant perceptions of illness between physicians and patients may be a barrier to conversations about prognosis and treatment options. These data highlight the urgent need to better inform patients of available HF treatment options and explore individual thresholds for considering LVAD therapy while patients are still ambulatory.7

These findings illustrate the difficulty in determining prognosis in advanced HF. Neither physicians’ nor patients’ perceptions of HF risk correlated with survival or need for urgent transplant or LVAD implant. Despite 40% of patients experiencing an endpoint in the Physician Perceived High Risk cohort, the other 60% did not suggesting that Physicians may at times overestimate risk. By contrast, even among Physician Perceived Low Risk patients, the number of events was high, as it has been demonstrated that advanced HF clinicians as well as patients tend to underestimate the risk in these ambulatory advanced HF patients.8 A unique aspect of these data is the potential additional prognostic value of combining physicians’ and patients’ perceptions of HF risk into a combined predictive model. There did appear to be a strong suggestion that the combined high risk cohort that included physicians’ and patients’ perceptions of risk had differing outcomes compared to the low risk cohort. Given the limited accuracy of a number of currently available HF prognostic models,9 the potential role of incorporating patients’ opinions regarding their own disease state as a novel variable in newer HF prognostic models warrants further exploration.

Finally, patients expressed incongruent opinions regarding the advanced HF treatment options in relation to other life sustaining therapies available for this group of patients. Among the physician identified high risk patients (those who one would have expected to have some discussions regarding life-sustaining therapies), only half had a power of attorney and only a third had discussions regarding life-sustaining therapies with their physician. Among the patients in this group who were willing to consider a LVAD—arguably one of the most invasive forms of life support available— two thirds would not have wanted a much simpler intervention such as a feeding tube. A willingness to consider an LVAD rather than less invasive supportive measures may reflect the considerable burden of HF among these still ambulatory patients, the hope that mechanical support can relieve symptoms, and a failure to appreciate the complex nature of this and other cardiac surgical interventions.

These findings underscore the many uncertainties and challenges faced by clinicians in having complex discussions regarding end of life and goals of care in an era of increasing clinical workload and decreasing time with patients. Physicians eliciting patient perceptions of their own level of illness may serve as an opportunity to approach the subject of advanced HF therapies. In addition, these findings suggest the need for educational interventions and decision aids to facilitate patient education about treatment options and HF prognosis as a supplement to face-to-face clinician-patient visits. Indeed, a recent randomized control trial of a video decision support tool did find that patients randomized to such an intervention found it to be acceptable and did have greater knowledge about end of life options afterwards.10 Studies utilizing such novel educational formats and decision aids are ongoing in patients facing destination therapy LVAD therapy, and could be important in the future.11 Taken together, these data support the systematic introduction of scheduled reviews of prognosis and treatment options for patients with advanced HF.2

Limitations

A major limitation of this study is that categorization of physician and patient HF risk as well as patients’ opinions on LVAD and life-sustaining therapies were made at the time of enrollment. It is likely that both perceptions of risk and patients’ opinions regarding life sustaining therapies and LVADs may have changed with their disease course—in particular immediately prior to the endpoints of death, LVAD, or transplant. It is also possible that some patients may not have understood that some life-sustaining therapies such as a feeding tube would be anticipated to be temporary, which may have influenced their responses. Although physicians were asked about risk of death or advanced therapy at one year, we included outcomes beyond one year to take advantages of longer term outcomes available in this cohort but acknowledge that risk prediction beyond one year is challenging for both patients and physicians. It is worth noting that a substantial number of these patients were referred to the enrolling centers for evaluation for LVAD or transplant, and that some of the patients had undergone a formal LVAD or transplant evaluation, which may have shaped risk perception. Furthermore, over half of the patients were followed by the participating LVAD/transplant program for at least a year, suggesting that a large percentage of patients may have had some exposure and discussions to these concepts before enrollment.

Conclusions

Among ambulatory advanced HF patients on oral therapy who were hospitalized for HF within the previous year, the risk of progression to transplant, LVAD, or death is relatively high. Physicians identified the majority of patients in this cohort to be at high risk for such progression, while patients tended to underestimate the severity of their illness. Despite discordant perceptions of illness severity, neither physicians nor patients were particularly accurate at predicting events. Despite a manifest concern for poor prognosis in this cohort of patients, robust discussions regarding life-sustaining therapies seem to be lacking. As there are growing treatment options, most notably with LVAD therapy, available for this cohort of advanced HF patients, earlier discussion regarding disease severity and treatment options are needed so that patients may make well-informed decisions.

Clinical Perspectives

Ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure (HF) on oral therapy who were hospitalized for HF within the previous year had a high risk of progression to transplant, left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation, or death; however, few patients recognized themselves to be at such risk for such disease progression. Furthermore, patients expressed inconsistent attitudes towards lifesaving treatment options, suggesting poor understanding of these therapies. As there are growing treatment options available for this group of patients—most notably with LVAD therapy—earlier discussions regarding HF prognosis and treatment options are needed to allow for patients to make well-informed decisions.

Translational Outlook

Improvements in left ventricular assist device (LVAD) technology have resulted in the broader application of this life-saving therapy to patients with advanced heart failure (HF). Despite the availability of this therapy, the present study highlights the difficulties that patients face as they attempt to integrate their own disease prognosis in relation to the timing and desire for LVAD implantation as well as other forms of life-sustaining treatments. As medical and device treatments for advanced HF continue to evolve, it will be important to incorporate patient-centered educational processes to facilitate the appropriate application of these treatments to the growing advanced HF patient population.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Lynne Warner Stevenson, MD, for the encouragement and formation of the MedaMACS Registry collaboration.

Funding/Support: This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN268201100025C and with funds received from the Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama for the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Dr. Ambardekar is supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association and by the Boettcher Foundation’s Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. DeVore reports receiving research support from the American Heart Association, Amgen, Maquet, Novartis, and Thoratec and consulting with Maquet. Dr. Teuteberg reports receiving advertising board and speaking honoraria from HeartWare, Abiomed, and CareDx as well as receiving support from Thoratec and Sunshine Heart. The remaining authors have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Breathett K, Allen LA, Ambardekar AV. Patient-centered care for left ventricular assist device therapy: current challenges and future directions. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31:313–20. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1928–52. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambardekar AV, Forde-McLean RC, Kittleson MM, et al. High early event rates in patients with questionable eligibility for advanced heart failure therapies: Results from the Medical Arm of Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (Medamacs) Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:722–30. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart GC, Kittleson MM, Cowger JA, et al. Who wants a left ventricular assist device for ambulatory heart failure? Early insights from the MEDAMACS screening pilot. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart GC, Kittleson MM, Patel PC, et al. INTERMACS (Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support) Profiling Identifies Ambulatory Patients at High Risk on Medical Therapy After Hospitalizations for Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2016:9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. Jama. 2008;299:2533–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estep JD, Starling RC, Horstmanshof DA, et al. Risk Assessment and Comparative Effectiveness of Left Ventricular Assist Device and Medical Management in Ambulatory Heart Failure Patients: Results From the ROADMAP Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1747–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorodeski EZ, Chu EC, Chow CH, Levy WC, Hsich E, Starling RC. Application of the Seattle Heart Failure Model in ambulatory patients presented to an advanced heart failure therapeutics committee. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:706–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Jankowski M, et al. Risk prediction models for mortality in ambulatory patients with heart failure: a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:881–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of an Advance Care Planning Video Decision Support Tool for Patients With Advanced Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;134:52–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIlvennan CK, Thompson JS, Matlock DD, et al. A Multicenter Trial of a Shared Decision Support Intervention for Patients and Their Caregivers Offered Destination Therapy for Advanced Heart Failure: DECIDE-LVAD: Rationale, Design, and Pilot Data. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31:E8–E20. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]