Abstract

Glioblastomas are among the most fatal brain tumors; however, the molecular determinants of their tumorigenic behavior are not adequately defined. In this study, we analyzed the role of KMT2A in the glioblastoma cell line U-87 MG. KMT2A knockdown promoted cell proliferation. Moreover, it increased the DNA methylation of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 and reduced the expression of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3. NOTCH1 or NOTCH3 activation inhibited U-87 MG cell proliferation, whereas NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 inhibition by shRNAs induced cell proliferation, thus demonstrating the tumor-suppressive ability of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 in U-87 MG cells. The induced cell proliferation caused by KMT2A knockdown could be nullified by using either constitutively active NOTCH1 or constitutively active NOTCH3. This result demonstrates that KMT2A positively regulates NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 and that this mechanism is essential for inhibiting the U-87 MG cell proliferation. The role of KMT2A knockdown in promoting tumor growth was further confirmed in vivo by transplanting U-87 MG cells into the brains of zebrafish larvae. In conclusion, we identified KMT2A-NOTCH as a negative regulatory cascade for glioblastoma cell proliferation, and this result provides important information for KMT2A- or NOTCH-targeted therapeutic strategies for brain tumors.

Keywords: KMT2A, NOTCH, glioma, zebrafish

INTRODUCTION

Lysine (K)-specific methyltransferase 2A [KMT2A, also known as mixed lineage leukemia 1 (MLL1)] encodes a transcriptional coactivator that regulates gene expression during early development and hematopoiesis [1]. Multiple chromosomal translocations involving this gene have been identified in certain acute lymphoid leukemias and acute myeloid leukemias [2]. The encoded protein contains multiple conserved functional domains. One of these domains, SET [Su(var), Enhancer of zeste, trx], is responsible for histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methyltransferase activity, which mediates chromatin modifications associated with epigenetic transcriptional activation. KMT2A is processed by the enzyme Taspase 1 into two fragments, MLLN and MLLC. These fragments reassociate and further assemble into different multiprotein complexes that regulate the transcription of specific target genes including many HOX genes [3]. In addition to H3K4 methyltransferase activity, KMT2A regulates DNA methylation. The CXXC domain in KMT2A binds to unmethylated CpG islands and protects CpG clusters within target genes such as HOXA9 from methylation [4–6]. KMT2A knockdown reverses the methylation protection status in the previously protected CpG clusters of HOXA9 [4].

KMT2A also plays an important role in maintaining specific gene expression for neurogenesis, hematopoiesis, and osteogenesis [7–9]. Conditional KMT2A knockout regulates the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of subventricular zone neural stem cells in postnatal mouse brains [7]. In zebrafish embryos, disrupting Kmt2a expression by using morpholino antisense oligonucleotides and a dominant-negative variant resulted in the downregulated proliferation of neural progenitors, premature differentiation of neurons, and impaired gliogenesis [9]. However, the role of KMT2A and its downstream signaling in brain tumors, particularly the role of epigenetic regulatory activity, remains to be clarified.

Genes belonging to the KMT2 family have been implicated in many mammalian cancers [10], and mutations in these genes are among the most frequent alterations in human cancer [11]. In hematopoietic cells, KMT2A translocations result in oncogenic fusion proteins that recruit DOT1-like histone H3K79 methyltransferase, which changes the epigenetic identity of the cells and drives a subset of infantile and adult leukemias [10, 12]. These studies have demonstrated the oncogenic character of KMT2A. However, the role of KMT2A in regulating tumor progression remains unclear, because most studies to date have focused on the function of the translocated KMT2A gene and the role of the fusion proteins resulting from translocation. Heddleston et al. demonstrated high expression levels of KMT2A in glioma stem cells (GSCs) [13]. KMT2A knockdown inhibited the expression of hypoxic-inducible factors and the vascular endothelial growth factor. In addition, KMT2A depletion reduced the self-renewal ability of GSCs and tumorigenicity [13, 14]. These studies have indicated that KMT2A is associated with glial-derived tumors.

In the current study, we examined the role of KMT2A in the U-87 MG glioblastoma cell line. We demonstrated that KMT2A is essential for the inhibition of tumor cell proliferation by using both in vitro and in vivo models. We further demonstrated that KMT2A knockdown increased NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 methylation, and the KMT2A-NOTCH1/3 cascade negatively regulated U-87 MG cell proliferation. Our results revealed the tumor-suppressive character of KMT2A, NOTCH1, and NOTCH3 in U-87 MG cells.

RESULTS

KMT2A knockdown induces glioma cell proliferation

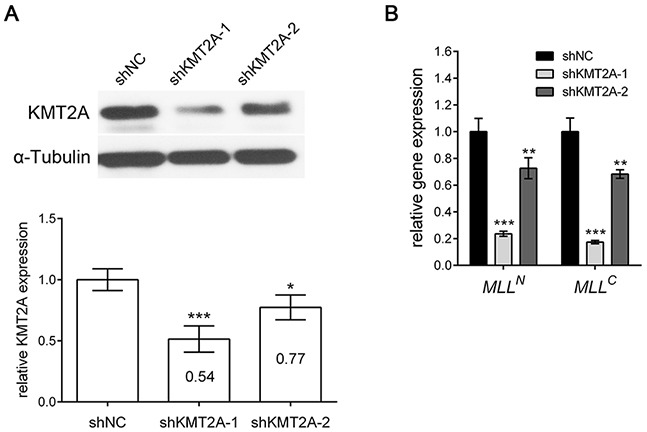

We investigated the role of KMT2A in U-87 MG cells (grade IV glioma cell line). We designed two shRNAs specifically targeting KMT2A (shKMT2A-1 and shKMT2A-2) and confirmed the effectiveness of KMT2A shRNAs through real-time RT-PCR and Western blot analysis. Cells transfected with shKMT2A exhibited significantly reduced KMT2A expression (Figure 1A). KMT2A is normally cleaved at two conserved sites, generating N-terminal p320 (MLLN) and C-terminal p180 (MLLC) fragments, which form a stable complex that localizes to subnucleus compartments [15]. Accordingly, we examined whether shKMT2A could affect these two fragments. The result reveals that shKMT2A downregulated the mRNA expression of both the N-form (MLLN) and C-form (MLLC) of KMT2A (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. shKMT2A effectively downregulates KMT2A expression.

shKMT2A downregulates the expression of KMT2A in U-87 MG cells. (A) Western blot analysis indicated that KMT2A expression was inhibited by shKMT2A-1 and shKMT2A-2, and the result was quantified. shKMT2A-1 was more efficient than shKMT2A-2. (B) RT-PCR demonstrated that shKMT2A inhibits the expression of MLLN and MLLC. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

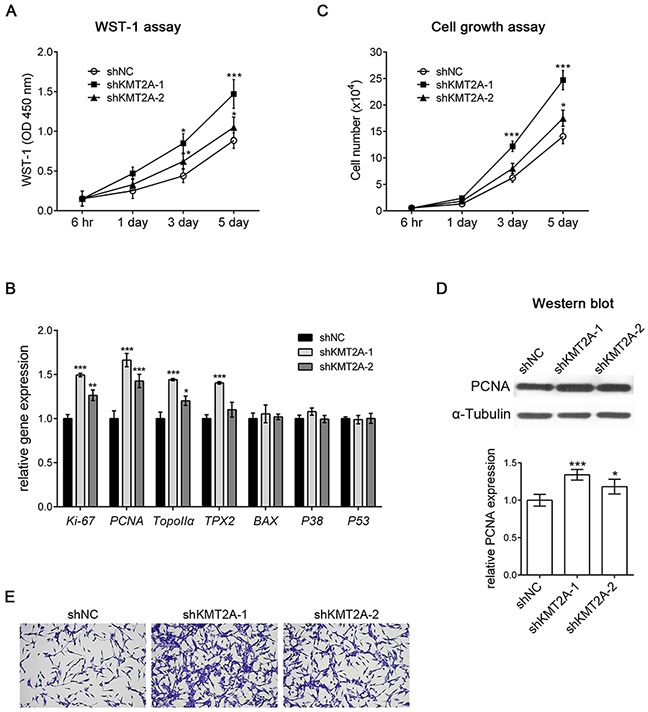

We next examined the effect of KMT2A knockdown in U-87 MG cells by using a WST-1 assay, and the result revealed that shKMT2A significantly induced U-87 cell proliferation (Figure 2A), indicating that KMT2A downregulation was essential for U-87 cell proliferation. We further analyzed cell proliferation and survival markers by using real-time RT-PCR, and the result demonstrated that the mRNA expression levels of the proliferation markers Ki-67, PCNA, Topoisomerase IIα (TopoIIα), and TPX2 were upregulated in KMT2A knockdown cells. By contrast, the apoptosis-related markers BAX, P38 MAPK, and P53 were unaffected by KMT2A knockdown (Figure 2B). To confirm the effect of shKMT2A on cell proliferation, the number of cells grown was measured using a cell growth assay (Figure 2C), and the proliferating cells were detected by proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), which was examined through Western blotting (Figure 2D). This result confirms that KMT2A is essential for inhibiting U-87 MG cell proliferation without affecting apoptosis.

Figure 2. shKMT2A induces U-87 MG cell proliferation.

(A) The effect of shKMT2A was examined using a WST-1 assay, which demonstrated that shKMT2A induces U-87 MG cell proliferation. (B) Cell proliferation and survival markers were analyzed using real-time RT-PCR. shKMT2A induces proliferation markers [Ki-67, PCNA, Topoisomerase IIα (TopoIIα), and TPX2] without a significant alteration of apoptosis markers (BAX, P38 MAPK, and P53). (C) Cell growth assay showing shKMT2A induces U-87 MG cell growth. (D) Western blot analysis indicated that shKMT2A upregulates the expression level of PCNA. (E) Representative images revealing that shKMT2A induces the growth of U-87 MG cells. Cells were stained with crystal violet. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

KMT2A upregulates the expression of NOTCH receptors through methylation

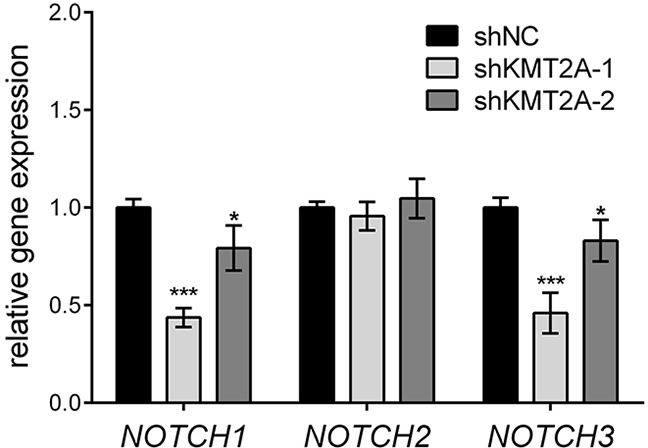

The Drosophila homologue of KMT2A, Trithorax (Trx), was demonstrated to collaborate with Notch in gene activation [16]. Mutations in H3K27me3 demethylase Utx, another member of the Trithorax Group (TrxG) of proteins, induce Notch signaling in Drosophila [17], suggesting that the Notch signaling pathway is regulated by KMT2A. Accordingly, we examined the expression of NOTCH receptors by using real-time RT-PCR. KMT2A knockdown significantly reduced the expression of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3, but it did not affect the expression of NOTCH2 (Figure 3). This result indicates that KMT2A is a positive regulator of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 transcription, thus suggesting that KMT2A selectively mediates NOTCH signaling.

Figure 3. KMT2A upregulates NOTCH signaling.

The expression of NOTCH genes was examined using real-time PCR. In KMT2A-deficient U-87 MG cells, the expression levels of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 were downregulated, whereas the expression level of NOTCH2 was unaffected when compared with the control. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

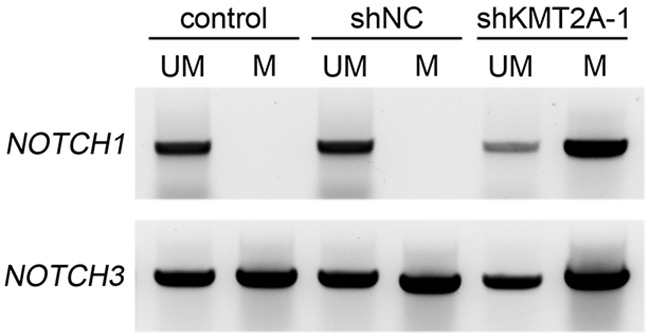

The CXXC domain in KMT2A binds to unmethylated CpG islands and protects CpG clusters within target genes from methylation [4–6]. CpG DNA methylation of NOTCH promoters contributes to decreased NOTCH expression [18–20]. To further confirm the direct regulation of KMT2A in NOTCH1 and NOTCH3, we used methylation-specific PCR (MSP), and the result revealed that the CpG islands in NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 promoters were unmethylated (Figure 4). In addition, the signaling observed for methylated NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 significantly increased upon KMT2A knockdown (Figure 4). This result indicates that KMT2A induces or maintains NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 expression by protecting NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 from DNA methylation.

Figure 4. Methylation-specific PCR reveals NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 methylation patterns in U-87 MG cell line.

M, primers specific for methylated DNA; UM, primers specific for unmethylated DNA. Signals were observed only in unmethylated NOTCH1, indicating that both alleles were unmethylated. By contrast, positive signals were observed in both methylated and unmethylated NOTCH3, indicating that only one allele was methylated. The signaling observed for methylated NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 significantly increased upon KMT2A knockdown. This experiment was performed using an EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit (Zymo Research). ***, p < 0.001.

KMT2A upregulates NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 in U-87 MG cell proliferation

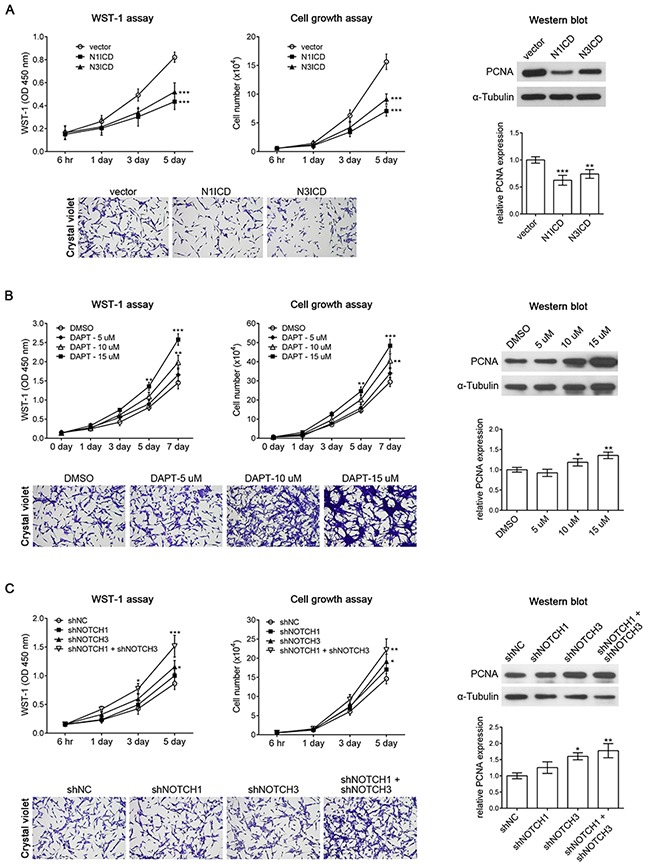

NOTCH1 acts as an oncoprotein in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Approximately 60% of human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma cases present NOTCH1 activation [21]. In addition, the oncogenic character of NOTCH signaling has been described in many types of tumors including breast carcinoma [22], hepatocellular carcinoma [23], pancreatic cancer [24], and brain tumors [25]. However, recent studies have revealed that NOTCH signaling can be either oncogenic or tumor suppressive, depending on the cellular context [26]. For example, NOTCH1 induces astrocytic gliomas, whereas NOTCH2 suppresses the growth of astrocytic gliomas [27]. Activation of the NOTCH pathway reduces glioma growth, and high NOTCH activity correlates with lower tumor grade and increased patient survival [28]. As mentioned, KMT2A is essential for the inhibition of cell proliferation and positively regulates NOTCH signaling, suggesting that NOTCH acts as a tumor suppressor in U-87 MG cells. We further confirmed the role of NOTCH in U-87 MG cells by overexpressing a constitutively active intracellular domain of NOTCH1 (N1ICD) or NOTCH3 (N3ICD). The results of the WST-1 assay, cell growth assay, and Western blot with PCNA antibody revealed that N1ICD or N3ICD inhibited U-87 MG cell proliferation (Figure 5A). In addition, the inhibition of NOTCH signaling by using the chemical inhibitor N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)- L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) induced U-87 MG cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5B). This result indicates that NOTCH activation is sufficient for inhibiting U-87 MG cell proliferation. DAPT inhibits γ-secretase activity and thus generally inhibits the activation of all NOTCH receptors [29]. Therefore, we individually inhibited NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 expression by using specific shRNA (shNOTCH1 [30, 31] and shNOTCH3 [32, 33], respectively). shNOTCH1 did not significantly affect the proliferation of U-87 MG cells, whereas shNOTCH3 only slightly induced the proliferation of U-87 MG cells (Figure 5C). However, double transfection of shNOTCH1 and shNOTCH3 significantly induced U-87 MG cell proliferation (Figure 5C). This result indicates that either NOTCH1 or NOTCH3 alone is sufficient for inhibiting U-87 MG cell proliferation, and that the double knockdown of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 reduces the inhibition effect and induces the upregulation of U-87 MG cell proliferation.

Figure 5. NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 suppresses U-87 MG cell proliferation.

(A) The result of the WST-1 assay, cell growth assay, and Western blot analysis with PCNA antibody revealed that overexpressing the constitutively active form of NOTCH1 (N1ICD) or NOTCH3 (N3ICD) inhibited U-87 MG cell proliferation. (B) U-87 MG cells treated with the NOTCH signaling inhibitor DAPT exhibited increased cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. DMSO was used as a control. (C) The WST-1 assay, cell growth assay, and Western blot analysis with PCNA antibody demonstrated that shNOTCH1 had no effect on U-87 MG cell proliferation, shNOTCH3 slightly induced U-87 MG cell proliferation, and double transfection of shNOTCH1 and shNOTCH3 exhibited significant induction of U-87 MG cell proliferation. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

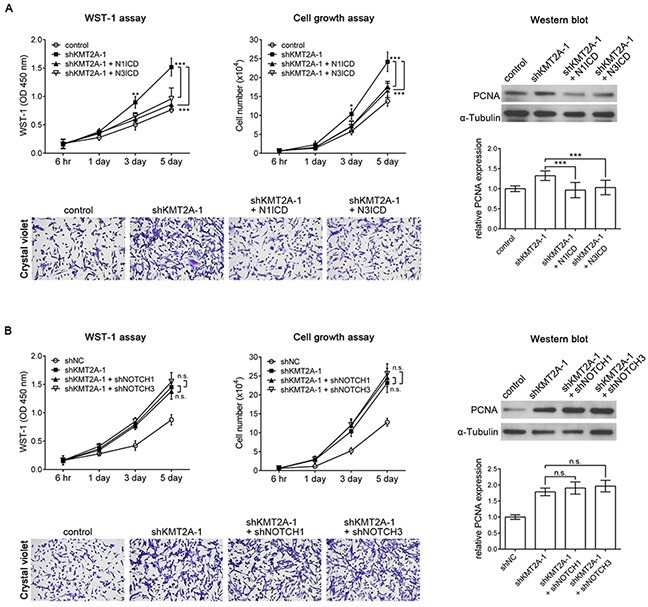

According to our results, KMT2A is essential for the inhibition of U-87 MG cell proliferation through the positive regulation of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3. To further confirm this finding, we expressed N1ICD or N3ICD in KMT2A-knockdown U-87 MG cells. KMT2A knockdown induced U-87 MG cell proliferation, and this phenotype could be abolished by N1ICD or N3ICD (Figure 6A). In addition, we performed knockdown of NOTCH1 or NOTCH3 expression in U-87 MG cells with a KMT2A-knockdown background. The result showed that NOTCH1 or NOTCH3 knockdown in KMT2A-knockdown U-87 MG cells did not further induce U-87 MG cell proliferation, compared with the effect of KMT2A knockdown (Figure 6B). This result further confirmed that KMT2A-NOTCH1/3 signaling inhibits U-87 cell proliferation.

Figure 6. N1ICD abolishes the KMT2A knockdown effect.

(A) KMT2A knockdown-induced cell proliferation was recovered using N1ICD or N3ICD, as determined by the WST-1 assay, cell growth assay, and Western blot analysis with PCNA antibody in U-87 MG cells. (B) shNOTCH1 or shNOTCH3 in shKMT2A-transfected U-87 MG cells did not further induce U-87 MG cell proliferation, compared with the effect of shKMT2A. n.s., not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

KMT2A knockdown promotes glioma tumorigenesis in vivo

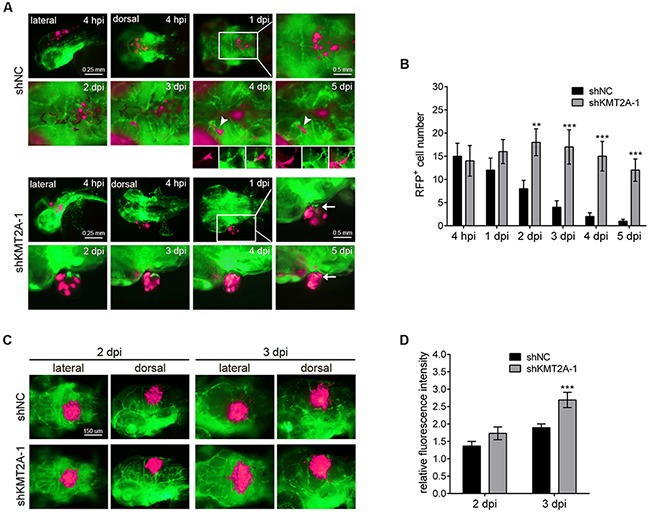

Because of the advantages of rapid growth and the optical clarity of zebrafish embryos, we transplanted the KMT2A-knockdown U-87 MG cells into zebrafish brains to investigate the role of KMT2A in glioma progression in vivo. We used the transgenic zebrafish line with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled blood vessels [Tg(fli1:egfp)] to facilitate the observation of tumor–endothelial cell interactions. The U-87 MG cells were labeled with red fluorescent protein (RFP) and implanted into the brains of 2-day postfertilization (dpf) embryos, followed by periodical examination from 4 hours to 5 days after implantation. Embryos injected with U-87 MG cells with scrambled shRNA were used as controls. In the control embryos, the transplanted U-87 MG cells gradually scattered, and the number of transplanted cells gradually decreased (Figure 7A). By contrast, the number of transplanted U-87 MG cells with KMT2A knockdown was significantly higher than the controls at all analysis stages. In particular, the transplanted tumor cells with KMT2A knockdown remained in a condensed bulk structure compared with the loose scattered cells of control embryos (Figure 7A). In addition, the transplanted tumor cells with KMT2A knockdown promoted angiogenesis by inducing zebrafish blood vessel growth into the tumor bulk (Figure 7B). This tumor angiogenesis has been demonstrated to be a critical step in localized tumor growth. To further improve the growth of the tumor graft, we treated the zebrafish with the immunosuppressant dexamethasone during transplantation [34–36]. Under the immunosuppressive condition, the U-87 MG cell mass grew in size, whereas the KMT2A knockdown further increased the size of the U-87 MG cell mass relative to the controls (Figure 7C, 7D). Therefore, the xenotransplantation result revealed KMT2A knockdown to be sufficient for promoting tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo.

Figure 7. KMT2A knockdown promotes tumor growth in zebrafish.

(A) U-87 MG cells were labeled with RFP (shown in fluorescent magenta), and approximately 50 cells were injected into the brains of Tg(fli1:egfp) fish in each experiment. Blood vessels are depicted by green fluorescent color. The transplanted zebrafish were imaged from 4 hours postimplantation (hpi) to 5 days postimplantation (dpi). Arrowheads depict tumor cells in the blood vessels, and arrows indicate the zebrafish blood vessels penetrating into the tumor tissues. (B) Quantification of transplanted cells. Quantification was performed by individually counting cells with red fluorescence (shown in fluorescent magenta), which indicated that the number of transplanted cells was significantly increased by KMT2A knockdown, compared with the control. shNC, scramble shRNA as negative control. (C) The immunosuppressant dexamethasone treatment increased the tumor growth. This result was quantified by measuring the red fluorescence intensity (D). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Our result reveals that KMT2A negatively acts on tumor growth, in contrast to our previous understanding of KMT2A as an oncogene in tumorigenesis [13]. KMT2A rearrangements account for approximately 10% of human leukemias, and more than 70 fusion proteins have been identified [10]. Accordingly, KMT2A fusion proteins are postulated to function to induce genes of oncogenic signaling and hence induce tumor progression. However, recent studies have demonstrated that KMT2A mutations are prevalent in many tumors [37–40], because KMT2A mutations in these tumors are nonsense or frameshift mutations that lead to the early termination of translation and result in truncated proteins with no methyltransferase activity. These studies have suggested that the loss of function of KMT2A is essential for tumor progression. The close family members of KMT2A, KMT2C, and KMT2D also have negative effects on tumor cell growth [41–43], supporting the tumor-suppressive role of the KMT2 family. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that in U-87 MG cells, KMT2A positively regulates NOTCH1 and NOTCH3, and this KMT2A–NOTCH1/3 cascade is essential for the inhibition of tumor cell proliferation. This finding further substantiates the tumor-suppressive role of KMT2A in tumor progression.

Our result also demonstrates a novel regulatory mechanism in glial tumor progression. The components of the NOTCH pathway have been reported to be deregulated in numerous hematological malignancies and brain tumors. However, the role of NOTCH signaling is not consistent in these tumors. For example, in medulloblastomas, NOTCH2 was shown to promote tumorigenesis, whereas NOTCH1 inhibited tumor growth [44]. NOTCH1 expression is higher in grade II and III gliomas but lower in more malignant gliomas [45, 46]. These studies have indicated that NOTCH signaling could be oncogenic or tumor suppressive in brain tumors, depending on the signaling initiated by different NOTCH receptors and different cell types. We demonstrated that KMT2A selectively upregulates different NOTCH receptors, and this mechanism may be crucial for driving NOTCH signaling to be oncogenic or tumor suppressive. In addition, KMT2A directly acted on NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 transcription through methylation. This result highlights the KMT2A–NOTCH suppression of cell proliferation as a unique regulatory cascade in glioblastomas. Currently, many inhibitors of NOTCH signaling, such as γ-secretase inhibitors, have been tested in clinical trials based on the assumption that NOTCH signaling is oncogenic [47]. In particular, these chemical inhibitors unselectively block signals transduced by all NOTCH receptors. Therefore, we suggest that these inhibitors should be used with caution because inhibiting NOTCH signaling may reduce the tumor-suppressive character in certain types of tumors and consequently induce tumor growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

U-87 MG cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco, USA), containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA) and antimycotic antibiotic (Gibco, USA).

shRNA knockdown of KMT2A expression

To establish a stable shRNA-tagged RFP-expressing U-87 MG cell line, the following shRNA construct were transfected, including a non-targeting pGPU6/RFP/scramble shRNA as negative control (shNC, target sequence: 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) and two pGPU6/RFP/shKMT2A (shKMT2A-1, target sequence: 5′-GGTGTTGTCGTCGTTGCAAAT-3′; shKMT2A-2, target sequence: 5′-GCGCCAAGCTCTTTGCTAAAG-3′) (purchased from BioTools). Transfection was performed using DreamFect™ Gold transfection reagent (OZ Biosciences). After 8 hours, the medium was replaced with G-418 (600 μg/mL, TOKU-E) selection medium. The stable shRNA-RFP expressing U-87 MG cells were grown in DMEM culture medium containing 10% FBS, antibiotics and G-418 (300 μg/mL). The shKMT2A-1 was more efficient in suppressing KMT2A expression in comparison to shKMT2A-2.

Generation of constitutively active NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 constructs

The NOTCH1 (NM_017617) intracellular domain (N1ICD) expression plasmid was generated by PCR from human cDNA. The N1ICD fragment contains the amino acid sequences from 1761 to 2555 of NOTCH1 (GenBank: NP_060087). The transcriptional start site ATG was added within forward primer, and the ClaI restriction site was created in both forward and reverse primers to favour sequential experiments. Primer sequences used were as follow: forward primer 5′- ATCGATATGCGGCAGCATGGCCAGCTC-3′ and reverse primer 5′- ATCGATCCTTGAAGGCCTCCGGAATGCG-3′. KOD FX DNA polymerase (TOYOBO) was used for PCR. The PCR product was ClaI (Roche), which was digested and purified (Geneaid). Following cloning into ClaI linearized pCS2(+) Myc vectors, in frame with the Myc-tag, and the produce was sequenced to ensure correct cloning and sequencing.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured tumor cells using Trizol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The PCR protocol included a denaturation programme (95°C for 10 min), followed by 40 cycles of amplification and quantification (95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min). Each sample was replicated at least three times.

Genomic DNA extraction and bisulphite conversion

Genomic DNA was extracted using the standard phenol-chloroform method, and subsequently, 500 ng DNA was input for bisulphite conversion using an EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Methylation specific PCR (MSP) analysis

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) was performed for the methylation analysis of the NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 promoters. The primers were designed within a CpG island region. The primers used to detect the methylated reaction were NOTCH1-MSP forward sequence 5′-CGTGATCGTAGTTTAGTTTTTGACGT-3′ and reverse sequence 5′-ATCTCGTAAAACGCGCCGTT-3′, which amplify a 263-bp product (positions −945 to −683); and a NOTCH3-MSP forward sequence 5′-TGTTTAGGTTGGAGCGTAGTGGTAC-3′ and reve-rse sequence 5′-AAAAATACAAAAATTAACTAAACGTA-3′, which amplify a 142-bp product (positions −230 to −89). The primers for the unmethylated reaction were NOTCH1-uMSP forward sequence 5′-TGTGATTGTAGTTTAGTTTTTGATGT-3′ and reverse sequence 5′-AAATCTCATAAAACACACCATT-3′, which amplify a 265-bp product (positions −947 to −683); and NOTCH3-uMSP forward sequence 5′-TGTTTAGGTTGGAGTGTAGTGGTATGA-3′ and reverse sequence 5′-AAAAATACAAAAATTAACTAAACATA-3′, which amplify a 142-bp product (positions −230 to −89). The PCR results were analyzed by DNA electrophoresis.

Western blot

Before lysis, the cells were washed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Total cell lysates were prepared by the addition of RIPA lysis buffer (Hycell) containing protease inhibitors (Calbiochem). Total protein was separated on bis-acrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Primary antibodies for KMT2A (1:500; 05-765; Millipore), PCNA (1:1000; Proteintech), or TUBULIN (1:10,000; T9026; Sigma-Aldrich) were incubated overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen) were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

Chemical treatment

Notch signaling was inactivated by treating with a chemical inhibitor of γ-secretase DAPT (EMD Millipore). Briefly, DAPT was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare a stock solution (10 mM). U-87 MG cells were seeded at 3 × 103 cells per well of a 96-well plate. Thereafter, the cells were treated with 200 μL DMEM medium supplemented with increasing concentrations of DAPT (1, 5, 10 and 15 μM). The control group was treated with an identical amount of DMSO.

Detection of cell viability and proliferation by WST-1 assay

The WST-1 assays were used to determine the effect of U-87 MG cell viability after transfection or DAPT treatment. For the WST-1 assay, cells were seeded at 3×103 cells/well in 96-well plates contained 200 μl cell growth medium. After the desired time point, they were then incubated with 10% WST-1 reagent (#630118; Clontech) for 30-90 minutes, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell growth assay

For the cell growth assay, 5000 cells/well were seeded in 24-well plates in triplicate and allowed to grow for 6 hours or 1, 3, or 5 days. At each time point, the cells were trypsinized and the numbers of cells were directly counted using a hemocytometer. Concurrently, 10 000 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates in duplicate. After growth for 5 days, the wells were rinsed twice with PBS, fixed for 10 minutes with cold absolute methanol in a freezer, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) in 25% methanol for 10 minutes. The stained cells were washed with ddH2O and allowed to air-dry, and images were captured with a 20× objective lens.

Zebrafish xenotransplantation

All experiments were performed in strict accordance with standard guidelines for zebrafish studies and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chang Gung University (IACUC approval number: CGU12–039). For zebrafish xenotransplantation, Tg(fli1:EGFP) strains of transgenic zebrafish embryos were maintained in 0.3% phenylthiourea (PTU, Sigma-Aldrich) after 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf). At 48 hpf, these embryos were dechorionated and anaesthetized in E3 buffer contained 0.3% phenylthiourea and 0.04 mg/mL tricaine (Sigma-Aldrich) before human cell injection. The RFP-expressing U-87 MG cells were washed and re-suspended in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS). Approximately 15 glioma-RFP cells were injected into the hindbrain ventricles of each embryo. After confirmation of proper visible tumor cells at the injection site, zebrafish were transferred individually into 24-well dishes and maintained in E3 buffer containing PTU at 34°C. Later, individual recipients were imaged for tumor growth under a fluorescence microscope (Leica). Dexamethasone was used as an immunosuppressant to improve the growth of the tumor graft. Larval fish of 48 hpf age were treated in 100 μg/mL of dexamethasone before transplantation [34–36]. The transplanted cells were quantified by counting the RFP-positive cells individually or measuring the relative fluorescence intensity of the RFP-labeled cells. Knockdown of KMT2A by monitored by detecting the C-terminal p180 (MLLC) fragments by using qRT-PCR at different time points in the zebrafish transplanted with tumor cells (supplementary Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the means ± SD determined from the indicated number of experiments. The statistical analysis was based on Student's t-tests for comparing two groups or one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. P values lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURES AND TABLE

Acknowledgments

We thank Shu-Yuan Hsu and Chia-Jung Yu for advice on handling the cell line. We are grateful to the Taiwan Zebrafish Core facility at ZeTH and the Zebrafish Core in Academia Sinica for providing the fish. This work was supported by grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPD3B0041, CMRPD3B0042 and CMRPD3B0043) and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (102-2311-B-182-002-MY3).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported by grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPD3B0041 and CMRPD3B0042) and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (102-2311-B-182-002-MY3).

REFERENCES

- 1.Marschalek R. Mixed lineage leukemia: roles in human malignancies and potential therapy. FEBS J. 2010;277:1822–1831. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohan M, Lin C, Guest E, Shilatifard A. Licensed to elongate: a molecular mechanism for MLL-based leukaemogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:721–728. doi: 10.1038/nrc2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu BD, Hess JL, Horning SE, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Altered Hox expression and segmental identity in Mll-mutant mice. Nature. 1995;378:505–508. doi: 10.1038/378505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erfurth FE, Popovic R, Grembecka J, Cierpicki T, Theisler C, Xia ZB, Stuart T, Diaz MO, Bushweller JH, Zeleznik-Le NJ. MLL protects CpG clusters from methylation within the Hoxa9 gene, maintaining transcript expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7517–7522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800090105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birke M, Schreiner S, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Mahr K, Titgemeyer F, Slany RK. The MT domain of the proto-oncoprotein MLL binds to CpG-containing DNA and discriminates against methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:958–965. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cierpicki T, Risner LE, Grembecka J, Lukasik SM, Popovic R, Omonkowska M, Shultis DD, Zeleznik-Le NJ, Bushweller JH. Structure of the MLL CXXC domain-DNA complex and its functional role in MLL-AF9 leukemia. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:62–68. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim DA, Huang YC, Swigut T, Mirick AL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Wysocka J, Ernst P, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chromatin remodelling factor Mll1 is essential for neurogenesis from postnatal neural stem cells. Nature. 2009;458:529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan X, Hu B, Liu JX, Feng X, Xiao W. Zebrafish mll gene is essential for hematopoiesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33345–33357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.253252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YC, Shih HY, Lin SJ, Chiu CC, Ma TL, Yeh TH, Cheng YC. The epigenetic factor Kmt2a/Mll1 regulates neural progenitor proliferation and neuronal and glial differentiation. Dev Neurobiol. 2015;75:452–462. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao RC, Dou Y. Hijacked in cancer: the KMT2 (MLL) family of methyltransferases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:334–346. doi: 10.1038/nrc3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, Xie M, Zhang Q, McMichael JF, Wyczalkowski MA, Leiserson MD, Miller CA, Welch JS, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heddleston JM, Wu Q, Rivera M, Minhas S, Lathia JD, Sloan AE, Iliopoulos O, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. Hypoxia-induced mixed-lineage leukemia 1 regulates glioma stem cell tumorigenic potential. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:428–439. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallo M, Ho J, Coutinho FJ, Vanner R, Lee L, Head R, Ling EK, Clarke ID, Dirks PB. A tumorigenic MLL-homeobox network in human glioblastoma stem cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:417–427. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh JJ, Ernst P, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Korsmeyer SJ. Proteolytic cleavage of MLL generates a complex of N- and C-terminal fragments that confers protein stability and subnuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:186–194. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.186-194.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bejarano F, Milan M. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms regulating hedgehog expression in the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2009;327:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herz HM, Madden LD, Chen Z, Bolduc C, Buff E, Gupta R, Davuluri R, Shilatifard A, Hariharan IK, Bergmann A. The H3K27me3 demethylase dUTX is a suppressor of Notch- and Rb-dependent tumors in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2485–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01633-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuang SQ, Fang Z, Zweidler-McKay PA, Yang H, Wei Y, Gonzalez-Cervantes EA, Boumber Y, Garcia-Manero G. Epigenetic inactivation of Notch-Hes pathway in human B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PloS one. 2013;8:e61807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rauen T, Grammatikos AP, Hedrich CM, Floege J, Tenbrock K, Ohl K, Kyttaris VC, Tsokos GC. cAMP-responsive element modulator alpha (CREMalpha) contributes to decreased Notch-1 expression in T cells from patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42525–42532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.425371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Y, Cao X, Xue X, Feng Z, Fan Q, Zheng Y, Feng C, Xu H, Xia C, Cheng Y. Development of hair cells in inner ear is associated with expression and promoter methylation of Notch-1 in postnatal mice. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:15542–15548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aster JC, Pear WS, Blacklow SC. Notch signaling in leukemia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:587–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo S, Liu M, Gonzalez-Perez RR. Role of Notch and its oncogenic signaling crosstalk in breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1815:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gil-Garcia B, Baladron V. The complex role of NOTCH receptors and their ligands in the development of hepatoblastoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Biol Cell. 2015;108:29–40. doi: 10.1111/boc.201500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avila JL, Kissil JL. Notch signaling in pancreatic cancer: oncogene or tumor suppressor? Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teodorczyk M, Schmidt MH. Notching on Cancer's Door: Notch Signaling in Brain Tumors. Front Oncol. 2014;4:341. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.South AP, Cho RJ, Aster JC. The double-edged sword of Notch signaling in cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu P, Zhang A, Jiang R, Qiu M, Kang C, Jia Z, Wang G, Han L, Fan X, Pu P. The different role of Notch1 and Notch2 in astrocytic gliomas. PloS one. 2013;8:e53654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28.Giachino C, Boulay JL, Ivanek R, Alvarado A, Tostado C, Lugert S, Tchorz J, Coban M, Mariani L, Bettler B, Lathia J, Frank S, Pfister S, et al. A Tumor Suppressor Function for Notch Signaling in Forebrain Tumor Subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:730–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geling A, Steiner H, Willem M, Bally-Cuif L, Haass C. A gamma-secretase inhibitor blocks Notch signaling in vivo and causes a severe neurogenic phenotype in zebrafish. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:688–694. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai MY, Fang F, Zou Y, Yi X, Ding YJ, Chen C, Tao ZZ, Chen SM. Downregulation of Notch1 induces apoptosis and inhibits cell proliferation and metastasis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:3111–3119. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martz CA, Ottina KA, Singleton KR, Jasper JS, Wardell SE, Peraza-Penton A, Anderson GR, Winter PS, Wang T, Alley HM, Kwong LN, Cooper ZA, Tetzlaff M, et al. Systematic identification of signaling pathways with potential to confer anticancer drug resistance. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra121. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alqudah MA, Agarwal S, Al-Keilani MS, Sibenaller ZA, Ryken TC, Assem M. NOTCH3 is a prognostic factor that promotes glioma cell proliferation, migration and invasion via activation of CCND1 and EGFR. PloS one. 2013;8:e77299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao WX, Zhuang X, Huang TT, Feng R, Lin JH. Effects of Notch2 and Notch3 on Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis of Trophoblast Cell Lines. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:867–874. doi: 10.7150/ijms.12935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore JC, Langenau DM. Allograft Cancer Cell Transplantation in Zebrafish. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;916:265–287. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-30654-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langenau DM, Ferrando AA, Traver D, Kutok JL, Hezel JP, Kanki JP, Zon LI, Look AT, Trede NS. In vivo tracking of T cell development, ablation, and engraftment in transgenic zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7369–7374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402248101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoletov K, Montel V, Lester RD, Gonias SL, Klemke R. High-resolution imaging of the dynamic tumor cell vascular interface in transparent zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17406–17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703446104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, Fulton L, Fulton RS, Zhang Q, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Dezso Z, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gui Y, Guo G, Huang Y, Hu X, Tang A, Gao S, Wu R, Chen C, Li X, Zhou L, He M, Li Z, Sun X, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Nat Genet. 2011;43:875–878. doi: 10.1038/ng.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, Robertson AG, Pashtan I, Shen R, Benz CC, Yau C, Laird PW, Ding L, Zhang W, Mills GB, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Kim DH, Lee S, Yang QH, Lee DK, Lee SK, Roeder RG, Lee JW. A tumor suppressive coactivator complex of p53 containing ASC-2 and histone H3-lysine-4 methyltransferase MLL3 or its paralogue MLL4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8513–8518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902873106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanda H, Nguyen A, Chen L, Okano H, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila ortholog of MLL3 and MLL4, trithorax related, functions as a negative regulator of tissue growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:1702–1710. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01585-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C, Liu Y, Rappaport AR, Kitzing T, Schultz N, Zhao Z, Shroff AS, Dickins RA, Vakoc CR, Bradner JE, Stock W, LeBeau MM, Shannon KM, et al. MLL3 is a haploinsufficient 7q tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:652–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan X, Mikolaenko I, Elhassan I, Ni X, Wang Y, Ball D, Brat DJ, Perry A, Eberhart CG. Notch1 and notch2 have opposite effects on embryonal brain tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7787–7793. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung HC, Corley LJ, Fuller GN, McCutcheon IE, Cote GJ. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein and Notch1 are independently re-expressed in glioma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1034–1041. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purow BW, Haque RM, Noel MW, Su Q, Burdick MJ, Lee J, Sundaresan T, Pastorino S, Park JK, Mikolaenko I, Maric D, Eberhart CG, Fine HA. Expression of Notch-1 and its ligands, Delta-like-1 and Jagged-1, is critical for glioma cell survival and proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2353–2363. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito N, Fu J, Zheng S, Yao J, Wang S, Liu DD, Yuan Y, Sulman EP, Lang FF, Colman H, Verhaak RG, Yung WK, Koul D. A high Notch pathway activation predicts response to gamma secretase inhibitors in proneural subtype of glioma tumor-initiating cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:301–312. doi: 10.1002/stem.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.