Introduction

The 2014 West African outbreak of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) was unprecedented in both its scope and impact, causing more cases and deaths than all previous outbreaks of EVD combined. In Liberia, after a devastating 14 year-long civil war, the country was left with a shattered health care system along with devastated country-wide infrastructure. Healthcare providers and hospital facilities have remained in extremely short supply. As the EVD outbreak spread widely and rapidly through Liberia, Bong County was severely affected. Bong County shares a common border with Guinea, and reported its first suspected case of EVD in June 2014.

By early 2015, 712 total cases of EVD were reported in Bong County along with 176 deaths (Ministry of Health, 2015) (see Figure 1), and 372 cases and 180 deaths were reported among healthcare providers throughout Liberia (UNICEF, 2015). As the outbreak progressed through West Africa, it was quickly recognized that the healthcare needs of affected countries were far beyond the capacity of local responders in terms of personnel, equipment and logistics (Grinnell et al., 2015). Multiple reports cited healthcare workers in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone as being undertrained, understaffed, and undersupplied to manage the growing EVD crisis (Boozary et al., 2014; Fowler et al., 2014; Grinnell et al., 2015). In Liberia for example, visits to Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) where two or more healthcare workers had probable, confirmed or suspected cases, found a variety of inadequate infection control precautions in place, ranging from shared gloves between providers or wearing of the same personal protective equipment (PPE) throughout a shift when caring for both patients with and without EVD (Matanock et al., 2014). The impact of EVD on healthcare in West Africa caused significant morbidity and mortality, but also by influenced perceptions of healthcare (Pellecchia et al., 2015) among both patients and the providers themselves. This impact spread far beyond affected patients and providers. Efforts to curb deeply rooted traditional cultural practices that contributed to the spread of EVD were problematic in multiple ways (Abramowitz et al., 2015; Pellecchia et al., 2015). In post-conflict countries such as Liberia, where there are already too few healthcare workers including midwives, the fear and mistrust surrounding the outbreak presented serious and long-lasting hurdles, which must be overcome in order to provide effective care.

Figure 1.

Map of EVD Impact in Liberia

Much of the research thus far has focused on the epidemiology of the EVD (Atkins et al., 2016; Lokuge et al., 2016; Pandey et al., 2014). However, there has been very little investigation into how frontline healthcare providers addressed, reacted to and afterwards, perceived the EVD pandemic. Therefore, the purpose of the study described here is to explore healthcare providers’ perceptions and reactions to the EVD epidemic.

Methods

This research was undertaken as part of a larger study that was in process during the EVD outbreak in Liberia. The original operations research, Innovation, Research, Operations, and Planned Evaluation for Mothers and Children (I-ROPE) was in the final year of a four-year study examining the impact of maternity waiting homes on maternal and newborn outcomes in rural Liberia (Lori et al., 2013a, 2013b). During the course of the I-ROPE project, the data revealed a steady increase in facility births among a sample of 10 rural health facilities and two local hospitals in Bong County Liberia. However, as reports of EVD escalated, the study team noted a negative trend in the number of women seeking facility-based deliveries within Bong County (Lori et al., 2015).

In response, the study team decided to undertake a descriptive, qualitative study to explore healthcare providers’ perceptions and reactions to the EVD epidemic. Institutional review board approval for the research was obtained from the investigating institution and the county health department where the focus groups were conducted.

Setting and Sample

According to the most recent census, Bong County is the third most populated county in Liberia, following Montserrado (which includes the capital city Monrovia) and Nimba counties, with an estimated population of 333,000 (Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services, 2013).

Qualitative data were obtained through focus group discussions with community health workers including traditional birth attendants (TBAs), government community health volunteers (gCHVs), nurses, physician assistants, and midwives. These focus groups took place in eight rural communities and three ETUs in Bong County.

Data Collection

Data were collected using semi-structured focus groups. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling. Potential participants were told the study team “would like to conduct focus groups about your experiences with Ebola.” A Liberian research nurse organized a date and time to visit the eight communities and three ETUs to meet with potential participants. Focus groups were conducted in private rooms at each location. Verbal consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection and all participants were reassured that declining participation would not impact their position and/or care at the clinic. All focus groups were audio taped and transcribed verbatim.

The focus groups were organized around a number of open-ended questions to understand each participant’s unique experience with EVD. Examples of open-ended questions included: (1) Tell us about your biggest fears for yourself as a community health worker because of Ebola. (2) How have people’s health behaviors changed because of Ebola? (3) Tell us about some of the challenges communities have faced because of Ebola. (4) Tell us about how you get information about Ebola.

Data Analysis

Qualitative analysis was completed using the constant comparative method of analysis (Glaser, 1992, 1978) to explore how healthcare practices and interactions may have changed related to EVD. The first two authors initially read through the data to secure general impressions. The next step involved each author independently reviewing all of the responses in a more detailed fashion to begin coding the data into categories and to record memos on noteworthy ideas. The first two authors then worked together to review these initial coding decisions and memos and grouped the categories into core themes until data saturation occurred. Consensus was achieved by all study authors on the core themes (Sandelowski and Barroso, 2003). To ensure trustworthiness the following activities were employed throughout the study process: methodological coherence, sampling adequacy, and collecting and analyzing data concurrently (Morse et al., 2002).

Findings

A variety of participants were recruited to provide a broad overview of how EVD was impacting healthcare interactions and the healthcare system in Liberia. The total sample size was 58 participants, including nurses (n=11), traditional birth attendants (TBAs; n=10), midwives (n=4), general community health volunteers (n=28), physician assistants (n=3), and others (n=2; community member and dispenser). These participants ranged in age from 27–65 years old. The majority of participants were male (n=31; 53.4%). Despite their interactions with the healthcare system, only a few of our participants reported that someone in their family had acquired EVD (n=4; 6.9%). See Table 1 for additional details on the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (n=58); n (%)

| Characteristic | Nurse (n=11) |

TBA (n=10) |

Midwives (n=4) |

gCHV (n= 28) |

Physician Assistant (n=3) |

Other (n=2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age | 29–54 | 37–65 | 37–60 | 27–56 | 36–52 | 21–43 |

| Mean (SD) | 36.45 (7.59) | 52.38 (8.83) | 43.75 (10.9) | 40.32 (9.20) | 44.67 (8.08) | 32 (15.56) |

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 21 (75.0) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Female | 5 (45.5) | 10 (100.0) | 3 (75.0) | 7 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Relationship Status | ||||||

| Single | 6 (54.5) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (25.0) | 12 (42.9) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) |

| Married | 5 (45.5) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (75.0) | 16 (57.1) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (50.0) |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Formal Schooling | ||||||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| < High School Graduate | 3 (27.3) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (25.0) | 6 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| High School Graduate | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 15 (53.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Some University or University Graduate | 7 (63.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (17.9) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Total number of children born to you | 1–8 | 3–16 | 2–5 | 1–8 | 2–5 | 0–5 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.36 (2.20) | 8.20 (3.85) | 3.5 (1.29) | 3.43 (1.91) | 4 (1.73) | 2.5 (3.54) |

|

| ||||||

| Living Children | 1–8 | 3–9 | 2–4 | 1–8 | 2–5 | 0–4 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.36 (2.20) | 5.70 (1.95) | 3 (0.82) | 3.43 (1.91) | 4 (1.73) | 2.00 (2.83) |

|

| ||||||

| Deceased Children | 0 | 0–7 | 0–2 | 0 | 0 | 0–1 |

| Mean (SD) | 0 (0.0) | 1.30 (2.54) | 0.50 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.50 (0.71) |

|

| ||||||

| Anyone in your family had EVD | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 9 (81.8) | 10 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 26 (92.9) | 3 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) |

Participants described five core themes related to changes in healthcare practices and interactions since the EVD outbreak. These five core themes were (1) fear, (2) resource constraints, (2) lack of knowledge and training, (4) stigma, and (5) shifting cultural practices. Each theme will be explored in more detail below.

Fear

Participants described a pervasive fear about EVD that permeated their daily lifestyle. Fears about EVD ranged from fear of contracting the disease to a fear of exposing others. Again and again, participants gave similar responses; that they worried for themselves, their families, and their community about contracting or dying from EVD. This sentiment is reflected in the statement of one 40 year old midwife, “The community members’ major fear is the sudden death of their loved ones.”

The rapid spread of EVD was also of serious concern to many of our participants. Not knowing the extent of the EVD outbreak or when it might be contained was a major source of worry and fear. These concerns were highlighted by a number of participants in their statements such as “Ebola don’t have limit” (34 year old gCHV) and “Ebola has no medicine” (52 year old gCHV). Meanwhile a 35 year old gCHV noted that there is widespread fear surrounding the EVD “because Ebola cannot be seen with the naked eye.” A 52 year old physician assistant summed up this fear of the rapid spread of EVD in his comment, “Ebola kills generations.”

Finally, providers themselves expressed fear about being on the frontlines of the outbreak. As they were often the first point of contact, they worried about contracting or spreading the disease due to their positions in the community as healthcare providers. This fear was summarized by a 33 year old nurse who noted, “we are [at] risk, [we are the] first to get in contact with patient.”

Resource Constraints

Basic resources were scarce and often unavailable throughout the EVD outbreak. Concerns with the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of basic supplies, and limited or no hand washing facilities—even makeshift ones, were noted frequently among participants’ responses. A lack of PPE (i.e., gloves, gowns, masks) was the most discussed resource constraint identified throughout the interviews. Personal protective equipment was reported as difficult to obtain, available in only the wrong size, or stiflingly hot. For example, one 37 year old midwife noted that “protection gear were (sic) not brought on time” while a 35 year old nurse reported that healthcare providers suffered “dehydration because of the type of PPE.” Healthcare providers had to make due with whatever supplies they had available which included, “using plastic bags on both hands while caring for Ebola patients.”

Additionally, many basic medical supplies, for example thermometers, were also in short supply or often so cheaply made that they were ineffective. Participants wanted to use non-contact thermometers (called Thermoflash), which were largely unavailable to them. This concern is echoed by one 32 year old gCHV who requested “improve PPEs and thermometers.”

Common rubber buckets were used in Liberia for hand washing, carrying drinking water, and to hold disinfectant during the height of the EVD outbreak, as many facilities and homes lack running water. Buckets became harder to purchase and were often largely unavailable. Many participants reported frustration surrounding the lack of buckets, which left them unable to wash their hands, risking exposure to themselves and others. When asked what supplies they needed, many reported the need for buckets above and beyond the need for PPE. When asking for parting thoughts as the focus groups concluded, one 29 year old gCHV stated “that buckets be provided for my community.” Meanwhile, a 55 year old TBA requested that “Buckets should be divided, and community members should wash their hands.”

Lack of Knowledge and Training

A lack of knowledge and training permeated both the community and healthcare sector. This was best summed up by a 52 year old physician assistant who noted that the top three challenges in identifying Ebola in Liberia included a “lack of knowledge, inadequate equipment in the hospital, lack of education on Ebola.” The EVD remained a confusing and concerning entity for many in the community. The mechanism of transmission was not well understood by many. Multiple participants expressed that their community had a lack of knowledge surrounding EVD. As one 30 year old male nurse noted, “Community member[s] don’t know the sign[s] and symptom[s] of Ebola.”

However, this lack of knowledge and training was not limited solely to community members. Healthcare providers noted they also had a lack of knowledge about EVD and limited training on how to use PPE and the additional equipment introduced to Liberia during the outbreak. This sentiment is reflected by a 47 year old nurse who noted, “We had no knowledge in using those equipment (sic) brought to us.” This lack of knowledge and training was evident among the international community as many struggled to answer questions about how EVD was spread and how to protect those taking care of patients affected by EVD.

Stigma

The community itself provides a strong support in terms of structure of daily activities and socialization for most people living in rural villages. When asked about the consequences of EVD for people who have recovered, many of our participants answered simply “stigmatization.” This stigmatization seemed to stem from concerns about others becoming infected by the survivor, causing harm to themselves, their families, and the community. This stigmatization extended beyond individuals and sometimes entire communities were ostracized. As one 29 year old nurse noted, “some communities have been stigmatized and isolated.”

This stigma led to confusion and mistrust surrounding visitors or those new to the community. For instance, one 35 year old gCHV noted that “people was (sic) not willing to accept them [survivors] in the communities.” Another 33 year old gCHV shared there is “no more allowing visitors.” Additionally, neighboring families, who might have previously shared parenting responsibilities for children and infants, as well as shared household chores, now felt uncertain about accepting these traditional roles, out of concern for infecting themselves or their families. This stigma of the family is illustrated by a 52 year old gCHV, “People stigmatized the children or relatives of victim[s].”

Shifting Cultural Practices

Citizens in rural areas of Liberia often participate in communal activities: from sharing meals together to participating in the preparation for burial of a deceased friend or relative. Unfortunately, EVD has brought about a number of cultural shifts highlighted by our participants. Amongst these shifts was a change in the way people work and interact with one another. Liberians generally greet one another with a hug or handshake. However, because of concerns surrounding EBV these practices have stopped. This change in interpersonal relations is summed up by a 29 year old nurse in her statement, “People[‘s] interaction with others has changed greatly. Reason is people are no longer relating to each other like before. Example is (sic) eating together, hugging, or shaking hands.” Additionally, community work activities, such as farming, have ceased. Some of our participants reflected that there are, “no more farming activities.”

Another cultural shift noted by many of our participants was the change in burial practices in Liberia. In West Africa, burials are often seen as a celebration of the life of the deceased and are ensconced with rituals such as bathing and preparing the body. The changes in burial practices are described by one 36 year old nurse, “no plating dead body hair, no bathing them, no more funeral for dead body.” As many of our participants reflected, “burial teams [are now] responsible for burial.”

Finally, there seemed to be mixed messages from our participants on whether or not EVD was changing birth practices. Some of our participants noted, “There is no more home delivery, no midwife[s] do delivery without PPE” while others responded that “community births increased”. Regardless, our participants agreed that women were concerned about having a safe delivery and that “no mother is now allowed to feed another person[‘s] baby.”

Discussion

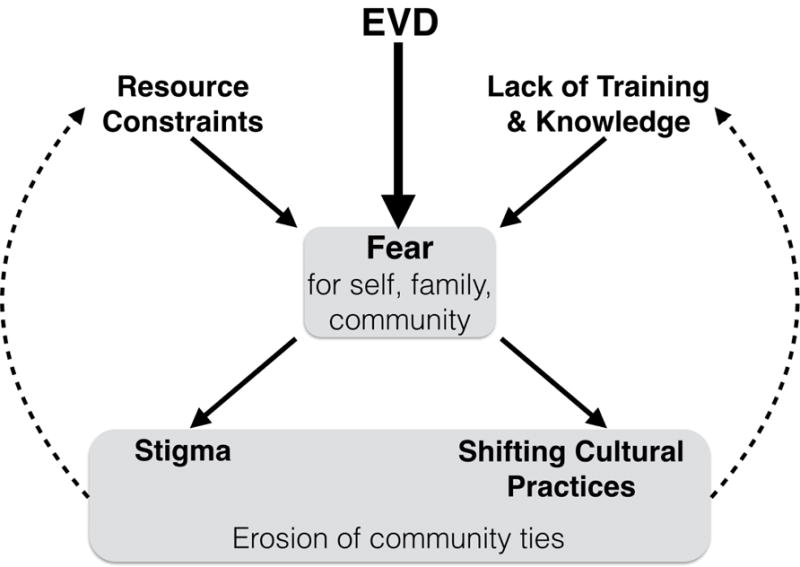

The EVD outbreak was declared over in Liberia on January 14, 2016, although two new cases of EVD were reported in Sierra Leone the very next week (World Health Organization, 2016). The presence of new cases highlights the need for ongoing education and preparedness of healthcare workers. This study represents only a small part of the larger ripple of impact the EVD epidemic is having and will continue to have on both healthcare workers and their communities in West Africa. In this work, we have begun to explore healthcare providers’ perceptions and reactions to the EVD epidemic, finding a core set of five themes; fear, resource constraints, lack of knowledge and training, stigma, and shifting cultural practices, which were common across the different focus group interviews. These themes are tied to one another, with a diagram of the potential inter-relationships represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Diagram of relationships between the core themes observed in the interviews.

The fear described by focus group participants was highly pervasive and felt at multiple levels—fear for themselves, their families, and their community. The breadth and depth of this fear was illustrated by the comment by one participant that “Ebola kills generations”. This fear was particularly heightened by the healthcare providers’ awareness that they were a front line of defense, and that their contact with patients could in turn spread EVD through each level of providers, families, and communities.

The theme of fear was compounded by two additional themes: resource constraints and lack of training/knowledge. While a lack of PPE was frequently discussed, so too was a lack of training on how to use the PPE, which allows healthcare workers to effectively care for patients while also protecting themselves (Matanock et al., 2014). This highlights the importance of connecting training with provision of resources. Basic needs and supplies (such as hand washing facilities, thermometers, and especially rubber buckets) were another heavily constrained resource (Forrester et al., 2014), with providers sometimes having to use plastic bags in place of gloves on their hands. The theme of resource constraints heavily underscored the importance of “better basics”—simple supplies like buckets that can significantly improve both provider safety and patient care. The theme of “lack of knowledge” extended beyond providers to the community at large. This lack of knowledge about EVD may have amplified the sense of fear for both the community and providers.

The secondary effects of the EVD epidemic led to two additional themes: stigma and changing cultural practices. Both of these themes relate to an erosion of community ties, and to the pervasive fear driven by EVD. Stigmatization was mentioned at multiple levels, from isolation of individuals to whole communities. This theme was closely tied to the theme of fear, with stigma stemming largely from concerns about infection spread. Relatedly, cultural practices have changed in response to the epidemic in ways that may also lead to reduced community ties and increased isolation. Participants reported reductions in both individual interactions like eating together, hugging, and shaking hands, as well as community-scale interactions such as community farming activities. Similar to the isolation/stigma theme, these changes have resulted from fear of infection. Some of these changes can directly help to reduce disease spread, such as the changes in burial practices, and perhaps changes in birth practices (although the participant comments about this were mixed). However, other changes, while they may help to reduce contact, may also have secondary effects that reduce the health and productivity of the community as a whole.

This work represents a preliminary analysis of healthcare workers reactions to the EVD epidemic, and has several limitations, such as potential bias in the sample, a need for further validation of findings, and the fact that these interviews only capture participant reactions at a single point in time. Future work is warranted to expand the sample of participants, examine the evolution of the reactions to EVD over time, and to consider using multiple approaches (qualitative and/or quantitative) to evaluate whether there is a convergence of themes across different methods (i.e. triangulation) (Denzin, 1978)

Nonetheless, several consistent themes emerged in this work. These themes were highly interconnected (Figure 2, and additional work to elucidate their interactions may help in preparing for subsequent outbreaks and other large-scale public health challenges. Broadly, we found that the EVD epidemic led to a pervasive fear, compounded by resource constraints and a lack of knowledge and training. EVD and the resulting fears/concerns about spreading infection led to an erosion of community ties, with both stigmatization and shifting cultural practices. The changes noted by the participants in the themes of stigma and shifting cultural practices included being more isolated, less communal, and less open to outside visitors. If these changes persist, it may be harder to reduce resource constraints and improve access to knowledge and training, making it more challenging to also improve access to public health in the region more broadly. This underscores the interrelatedness of these themes, and highlights the importance of tackling them together rather than individually.

Conclusion

The EVD epidemic has been declared over, but challenges remain as the focus shifts from response and recovery, to future preparedness. This study can help to inform policymakers and planners by providing evidence from healthcare workers who were on the ground during the epidemic. A solid understanding of the needs of healthcare workers such as presented in this manuscript can assist in preparedness activities in order to more comprehensively address future outbreaks.

Contributor Information

Sue Anne Bell, University of Michigan School of Nursing, 400 North Ingalls Rm 3340, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Michelle L. Munro-Kramer, Assistant Professor, University of Michigan School of Nursing, 400 North Ingalls Rm 3188, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Marisa C. Eisenberg, Assistant Professor, Epidemiology, M5166 SPH II, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-202.

Garfee Williams, Health Technical Advisor, Africare, 1000 Monrovia 10, Liberia.

Patricia Amarah, Health Technical Advisor, Africare, 1000 Monrovia 10, Liberia.

Jody R. Lori, Associate Professor, University of Michigan School of Nursing, 400 North Ingalls Rm 3320A, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

References

- Abramowitz SA, McLean KE, McKune SL, Bardosh KL, Fallah M, Monger J, Tehoungue K, Omidian PA. Community-centered responses to Ebola in urban Liberia: the view from below. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins KE, Pandey A, Wenzel NS, Skrip L, Yamin D, Nyenswah TG, Fallah M, Bawo L, Medlock J, Altice FL, Townsend J, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Galvani AP. Retrospective Analysis of the 2014–2015 Ebola Epidemic in Liberia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boozary AS, Farmer PE, Jha AK. The Ebola Outbreak, Fragile Health Systems, and Quality as a Cure. JAMA. 2014;312:1859–1860. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N. Sociological Methods. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester JD, Pillai SK, Beer KD, Neatherlin J, Massaquoi M, Nyenswah TG, Montgomery JM, De Cock K. Assessment of ebola virus disease, health care infrastructure, and preparedness - four counties,Southeastern Liberia, august 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:891–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler RA, Fletcher T, Fischer WA, Lamontagne F, Jacob S, Brett-Major D, Lawler JV, Jacquerioz FA, Houlihan C, O’Dempsey T, Ferri M, Adachi T, Lamah MC, Bah EI, Mayet T, Schieffelin J, McLellan SL, Senga M, Kato Y, Clement C, Mardel S, Vallenas Bejar De Villar RC, Shindo N, Bausch D. Caring for Critically Ill Patients with Ebola Virus Disease. Perspectives from West Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:733–737. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1514CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Advances in the methodology of grounded theory: Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell M, Dixon MG, Patton M, Fitter D, Bilivogui P, Johnson C, Dotson E, Diallo B, Rodier G, Raghunathan P. Ebola Virus Disease in Health Care Workers–Guinea, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1083–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6438a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services. Bong County Profile [WWW Document] 2013 URL http://www.lisgis.net/county.php?&fd0e78b77a58d689bbb27b3e1c037717=Qm9uZw%3D%3D (accessed 3.16.16).

- Lokuge K, Caleo G, Greig J, Duncombe J, McWilliam N, Squire J, Lamin M, Veltus E, Wolz A, Kobinger G, de la Vega MA, Gbabai O, Nabieu S, Lamin M, Kremer R, Danis K, Banks E, Glass K. Successful Control of Ebola Virus Disease: Analysis of Service Based Data from Rural Sierra Leone. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lori JR, Munro ML, Moore JE, Fladger J. Lessons learned in Liberia: preliminary examination of the psychometric properties of trust and teamwork among maternal healthcare workers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013a;13:134. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lori JR, Munro ML, Rominski S, Williams G, Dahn BT, Boyd CJ, Moore JE, Gwenegale W. Maternity waiting homes and traditional midwives in rural Liberia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013b;123:114–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lori JR, Rominski SD, Perosky JE, Munro ML, Williams G, Bell SA, Nyanplu AB, Amarah PNM, Boyd CJ. A case series study on the effect of Ebola on facility-based deliveries in rural Liberia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:254. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0694-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matanock A, Arwady MA, Ayscue P, Forrester JD, Gaddis B, Hunter JC, Monroe B, Pillai SK, Reed C, Schafer IJ, Massaquoi M, Dahn B, De Cock KM. Ebola virus disease cases among health care workers not working in Ebola treatment units–Liberia, June-August, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1077–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Liberia Ebola Daily Sitrep no 301 for 12th March 2015. Monrovia, Liberia: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Atkins KE, Medlock J, Wenzel N, Townsend JP, Childs JE, Nyenswah TG, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Galvani AP. Strategies for containing Ebola in West Africa. Science (80-) 2014;346:991–999. doi: 10.1126/science.1260612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellecchia U, Crestani R, Decroo T, Van den Bergh R, Al-Kourdi Y. Social Consequences of Ebola Containment Measures in Liberia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology project. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:781–820. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Liberia Ebola Situation Report no 76 11 March 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ebola Situation Report - 2 March 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: 2016. [Google Scholar]