Abstract

Background

Thirty-one states approved Medicaid expansion following implementation of the Affordable Care Act. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of Medicaid expansion on cardiac surgery volume and outcomes comparing one state that expanded to one that did not.

Methods

Data from the Virginia (non-expansion state) Cardiac Services Quality Initiative and the Michigan (expanded Medicaid, April 2014) Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons Quality Collaborative were analyzed to identify uninsured and Medicaid patients undergoing coronary bypass graft and/or valve operations. Demographics, operative details, predicted risk scores, and morbidity and mortality rates, stratified by state and compared across era (Pre-expansion: 18 months before vs. Post-expansion: 18 months after), were analyzed.

Results

In Virginia, there were no differences in volume between eras; while in Michigan there was a significant increase in Medicaid volume (54.4% [558/1026] vs. 84.1% [954/1135], P<0.001) and corresponding decrease in uninsured volume. In Virginia Medicaid patients, there were no differences in predicted risk of morbidity or mortality (PROMM) or postoperative major morbidities. In Michigan Medicaid patients, a significant decrease in PROMM (11.9% [8.1–20.0%] vs. 11.1% [7.7–17.9%], P=0.02) and morbidities (18.3% [102/558] vs. 13.2% [126/954], P=0.008) was identified. Post-expansion was associated with a decreased risk-adjusted rate of major morbidity (odds ratio, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–0.91; P=0.01) in Michigan Medicaid patients.

Conclusions

Medicaid expansion was associated with fewer uninsured cardiac surgery patients and improved predicted risk scores and morbidity rates. In addition to improving healthcare financing, Medicaid expansion may positively impact patient care and outcomes.

Classifications: Cardiac, health policy, outcomes, quality care, management

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law on March 23, 2010, in an effort to provide affordable, quality healthcare to all Americans.[1] A major pillar of the comprehensive reform package was the expansion of Medicaid, which would provide insurance coverage to all Americans under 65 years of age earning less than 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL).[2] Although the constitutionality of the ACA was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) vs. Sebelius, provisions requiring states to expand Medicaid were deemed “unconstitutionally coercive.”[3,4] State governments therefore became responsible for deciding whether or not to expand Medicaid; 31 of which (plus the District of Columbia) have decided to do so, recognizing the financial implications and contentious political environment.[5,6]

The effect of primary payer status on access to medical care, affordability, and quality has long been debated. Some studies concluded that payer status is not associated with outcomes, instead identifying risk factors and comorbidities as important predictors,[7,8] while others have identified a significant relationship between the two.[9,10] In a series of publications utilizing the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database, Medicaid payer status was associated with increased rates of risk-adjusted mortality and worse outcomes. Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and cardiac valve operations had longer lengths of stay and higher costs if they had Medicaid, as opposed to those with Medicare, private insurance, or no insurance.[11,12]

Considering that these analyses were completed prior to the ACA, the purpose of this study was to determine the impact of Medicaid expansion on improving access to healthcare and outcomes, using validated cardiac surgery databases from two states that made independent and different decisions regarding Medicaid expansion. We hypothesized that expansion of Medicaid in Michigan would decrease uninsured cardiac surgery volume and improve outcomes as compared with Virginia, a state that declined expansion. Improving the understanding of the effects of Medicaid expansion on the delivery of healthcare and patient outcomes may help state governments make informed policy decisions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval at both institutions. We analyzed prospectively collected data from the Virginia Cardiac Services Quality Initiative (VCSQI) and the Michigan Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons Quality Collaborative (MSTCVS-QC), both of which contain The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery data. VCSQI consists of 18 cardiac surgery member-sites in Virginia, while MSTCVS-QC captures all 33 non-federal hospitals performing adult cardiac surgery in Michigan. STS data are abstracted at each participating institution by trained coordinators and consist of demographic, payer status, risk factor, perioperative, morbidity, mortality, discharge, and readmission data on patients over the age of 18. The STS database is recognized as one of the leading national registry initiatives focused on improving surgical outcomes and healthcare quality.[13]

After implementation of the ACA, Michigan expanded Medicaid in April 2014, to provide coverage for all adults making less than 138% of FPL. [14] Conversely, the Virginia government decided not to expand Medicaid, and continued to provide traditional Medicaid coverage for pregnant women and children up to 143% of FPL and disabled adults up to 80% of FPL.[15] Analyses were completed on patients undergoing cardiac surgery during the 18 months prior to the start of Medicaid expansion in Michigan (October 2012 to April 2014, Pre-expansion era), and during the 18 months thereafter (April 2014 to September 2015, Post-expansion era).

Patient Selection

This study included Medicaid and uninsured patients ≥ 18 years of age who underwent CABG or valve operations in Virginia (VCSQI) and Michigan (MSTCVS-QC) between October 2012 and September 2015. We excluded patients without risk scores, including predicted risk of morbidity or mortality (PROMM) and predicted risk of mortality, which facilitate the normalization of observed to expected outcomes across institutions.

Variables

The primary endpoint for this study was rate of major morbidity (reoperation, stroke, kidney failure, deep sternal wound infection, or ventilator support > 24 hours) within 30 days postoperatively. Mortality was not chosen as the primary outcome because event rates are historically low following CABG and valve operations. The primary exposure variable was era.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis was performed simultaneously on data from VCSQI and MSTCVS-QC comparing patient demographics, case specifics, predicted risk scores, and outcomes between eras. Analyses were completed on three cohorts: Medicaid patients only (excluding dual-eligible Medicare/Medicaid patients), uninsured patients only, and combined Medicaid and uninsured patients. Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables respectively. Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. Unadjusted and adjusted post-expansion odds ratios for morbidity and mortality were calculated using multivariable logistic regression. Odds of major morbidity were adjusted for PROMM, and odds of 30-day mortality were adjusted for predicted risk of mortality. Alpha level for significance was 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata, version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Cardiac Surgery Patients

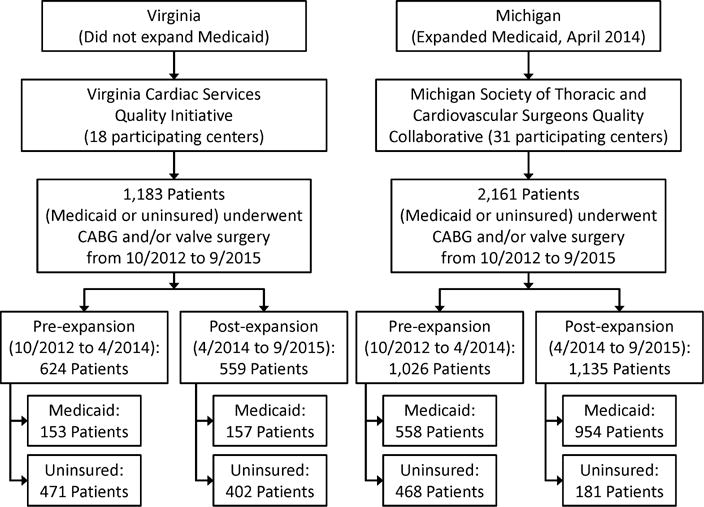

A total of 1,183 uninsured or Medicaid patients underwent CABG and/or cardiac valve operations between October 2012 and September 2015 in Virginia, while in Michigan, there were 2,161 patients (Figure 1). There were no differences in Medicaid (24.5% [153/624] vs. 28.1% [157/559], P=0.20) or uninsured volume (75.5% [471/624] vs. 71.9% [402/559], P=0.20) between eras in Virginia; while in Michigan, there was a significant increase in Medicaid volume (54.4% [558/1026] vs. 84.1% [954/1135], P<0.001) and corresponding decrease in uninsured volume (45.6% [468/1026] vs. 15.9% [181/1135], P<0.001). In all three cohorts of both states, there were no differences in patient age, sex, or BMI between eras, except for the median age of uninsured patients in Michigan (55 vs. 58 years, P=0.02) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Medicaid and uninsured cardiac surgery patients in Virginia and Michigan

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics

| Virginia | Michigan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | |

| Medicaid | ||||||

| Number of patients | 153 | 157 | 558 | 954 | ||

| Age, y | 56 (50–61)a | 57 (51–62) | 0.35 | 56 (50–61) | 56 (49–60) | 0.74 |

| Female | 62 (40.5)b | 58 (36.9) | 0.52 | 192 (34.4) | 328 (34.4) | 0.99 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.0 (25.1–33.8) | 29.5 (24.5–35.0) | 0.90 | 29.3 (25.3–34.3) | 29.4 (25.0–34.5) | 0.56 |

| Uninsured | ||||||

| Number of patients | 471 | 402 | 468 | 181 | ||

| Age, y | 56 (50–61) | 56 (50–61) | 0.79 | 55 (50–60) | 58 (53–61) | 0.02 |

| Female | 136 (28.9) | 121 (30.1) | 0.69 | 107 (22.9) | 41 (22.7) | 0.95 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.7 (25.7–32.4) | 28.9 (24.8–33.4) | 0.70 | 29.3 (25.6–33.5) | 28.1 (25.0–32.9) | 0.07 |

| Combined | ||||||

| Number of patients | 624 | 559 | 1026 | 1135 | ||

| Age, y | 56 (50–61) | 56 (50–61) | 0.43 | 56 (50–60) | 56 (50–60) | 0.51 |

| Female | 198 (31.7) | 179 (32.0) | 0.91 | 299 (29.1) | 369 (32.5) | 0.09 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.8 (25.5–32.9) | 29.0 (24.8–33.8) | 0.82 | 29.3 (25.5–33.8) | 29.2 (25.0–34.4) | 0.78 |

Median (interquartile range), all such values

Number (%), all such values

BMI=body mass index.

In Virginia and Michigan, CABG was the most common operation performed, followed by single valve replacement. There were no differences in types of operations, elective/urgent/emergent case status, or reoperation status between eras in either state (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Operative case specifics

| Virginia | Michigan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | ||

| Medicaid | |||||||

| Number of patients | 153 | 157 | 558 | 954 | |||

| Case Mix | |||||||

| CABG only | 99 (64.7)a | 105 (66.9) | 0.61 | 409 (73.3) | 716 (75.1) | 0.61 | |

| AVR only | 15 (9.8) | 14 (8.9) | 53 (9.5) | 99 (10.4) | |||

| MVR only | 19 (12.4) | 12 (7.6) | 29 (5.2) | 47 (4.9) | |||

| AVR+CABG | 9 (5.9) | 5 (3.2) | 21 (3.8) | 32 (3.4) | |||

| MVR+CABG | 4 (2.6) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (0.9) | 12 (1.3) | |||

| MV Repair±CABG | 7 (4.6) | 5 (3.2) | 41 (7.3) | 48 (5.0) | |||

| Case Status | |||||||

| Elective | 71 (46.4) | 64 (40.8) | 0.59 | 219 (39.3) | 373 (39.1) | 0.41 | |

| Urgent | 79 (51.6) | 89 (56.7) | 326 (58.4) | 547 (57.3) | |||

| Emergent | 3 (2.0) | 4 (2.5) | 13 (2.3) | 34 (3.6) | |||

| Reoperation Status | |||||||

| First operation | 141 (92.2) | 148 (94.3) | 0.56 | 534 (95.7) | 917 (96.1) | 0.41 | |

| First reoperation | 9 (5.9) | 8 (5.1) | 21 (3.8) | 36 (3.8) | |||

| Reoperation (≥2) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | |||

| Uninsured | |||||||

| Number of patients | 471 | 402 | 468 | 181 | |||

| Case Mix | |||||||

| CABG only | 379 (80.5) | 319 (79.4) | 0.96 | 370 (79.1) | 146 (80.7) | 0.55 | |

| AVR only | 40 (8.5) | 33 (8.2) | 34 (7.3) | 10 (5.5) | |||

| MVR only | 17 (3.6) | 12 (3.0) | 15 (3.2) | 3 (1.7) | |||

| AVR+CABG | 11 (2.3) | 8 (2.0) | 15 (3.2) | 6 (3.3) | |||

| MVR+CABG | 14 (3.0) | 9 (2.2) | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| MV Repair±CABG | 10 (2.1) | 11 (2.7) | 30 (6.4) | 15 (8.3) | |||

| Case Status | |||||||

| Elective | 102 (21.7) | 103 (25.6) | 0.15 | 103 (22.0) | 30 (16.6) | 0.30 | |

| Urgent | 334 (71.2) | 281 (69.9) | 341 (72.9) | 142 (78.5) | |||

| Emergent | 33 (7.0) | 18 (4.5) | 24 (5.1) | 9 (5.0) | |||

| Reoperation Status | |||||||

| First operation | 456 (96.8) | 389 (96.8) | 0.99 | 456 (97.4) | 176 (97.2) | 0.79 | |

| First reoperation | 14 (3.0) | 12 (3.0) | 11 (2.4) | 5 (2.8) | |||

| Reoperation (≥2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |||

| Combined | |||||||

| Number of patients | 624 | 559 | 1026 | 1135 | |||

| Case Mix | |||||||

| CABG only | 478 (76.6) | 424 (75.8) | 0.75 | 779 (75.9) | 862 (75.9) | 0.82 | |

| AVR only | 55 (8.8) | 47 (8.4) | 87 (8.5) | 109 (9.6) | |||

| MVR only | 36 (5.8) | 24 (4.3) | 44 (4.3) | 50 (4.4) | |||

| AVR+CABG | 20 (3.2) | 13 (2.3) | 36 (3.5) | 38 (3.3) | |||

| MVR+CABG | 18 (2.9) | 11 (2.0) | 9 (0.9) | 13 (1.2) | |||

| MV Repair±CABG | 17 (2.7) | 16 (2.9) | 71 (6.9) | 63 (5.6) | |||

| Case Status | |||||||

| Elective | 173 (27.8) | 167 (29.9) | 0.29 | 322 (31.3) | 403 (35.5) | 0.11 | |

| Urgent | 413 (66.4) | 370 (66.2) | 667 (65.0) | 689 (60.7) | |||

| Emergent | 36 (5.8) | 22 (3.9) | 37 (3.6) | 43 (3.8) | |||

| Reoperation Status | |||||||

| First operation | 597 (95.7) | 537 (96.1) | 0.79 | 990 (96.5) | 1093 (96.3) | 0.44 | |

| First reoperation | 23 (3.7) | 20 (3.6) | 32 (3.1) | 41 (3.6) | |||

| Reoperation (≥2) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | |||

Number (%), all such values

AVR=aortic valve replacement, CABG=coronary artery bypass graft operation, MVR=mitral valve replacement, MV Repair±CABG=mitral valve repair with or without CABG.

Predicted Risk Scores

In Virginia Medicaid patients, there were no differences between eras in PROMM or predicted risk of mortality, however in Michigan, post-expansion Medicaid patients had significantly lower PROMM (11.9% [8.1–20.0%] vs. 11.1% [7.7–17.9%], P=0.02) and lower predicted risk of mortality (1.0% [0.5–1.9%] vs. 0.8% [0.5–1.6%], P=0.06) (Table 3). Uninsured patients in Virginia had similar PROMM and predicted risk of mortality rates regardless of era, while in Michigan, a significant increase was identified in uninsured patients in both PROMM (10.8% [7.3–18.4%] vs. 13.5% [8.2–21.5%], P=0.006) and predicted risk of mortality (0.8% [0.5–1.5%] vs. 1.0% [0.6–1.9%], P=0.004) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Preoperative predicted risk scores

| Virginia | Michigan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | |

| Medicaid | ||||||

| Number of patients | 153 | 157 | 558 | 954 | ||

| PROMM, % | 14.0 (8.7–24.9)a | 13.2 (8.7–21.3) | 0.59 | 11.9 (8.1–20.0) | 11.1 (7.7–17.9) | 0.02 |

| PROM, % | 1.1 (0.6–2.3) | 0.9 (0.6–2.5) | 0.85 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | 0.8 (0.5–1.6) | 0.06 |

| Uninsured | ||||||

| Number of patients | 471 | 402 | 468 | 181 | ||

| PROMM, % | 12.4 (8.1–20.9) | 12.0 (8.3–18.6) | 0.56 | 10.8 (7.3–18.4) | 13.5 (8.2–21.5) | 0.006 |

| PROM, % | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 0.8 (0.5–1.6) | 0.37 | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) | 0.004 |

| Combined | ||||||

| Number of patients | 624 | 559 | 1026 | 1135 | ||

| PROMM, % | 12.6 (8.2–21.7) | 12.4 (8.4–19.1) | 0.50 | 11.6 (7.6–18.9) | 11.3 (7.8–18.4) | 0.53 |

| PROM, % | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 0.46 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.78 |

Median (interquartile range), all such values

PROM=predicted risk of mortality, PROMM=predicted risk of morbidity or mortality.

Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality Rates

In Virginia, major morbidity and 30-day mortality rates were not significantly different between eras for Medicaid patients, uninsured patients, or combined (Table 4). In Michigan Medicaid patients, a significant decrease in the frequency of postoperative major morbidity was identified (18.3% [102/558] vs. 13.2% [126/954], P=0.008). This decrease was also observed in the Michigan combined cohort (18.3% [188/1026] vs. 15.1% [171/1135], P=0.04). There were no significant differences in any of the three Michigan cohorts in terms of 30-day mortality rates between eras, although the increase in mortality in post-expansion uninsured patients neared significance (1.1% [5/468] vs. 3.3% [6/181], P=0.05) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Morbidity and mortality outcomes

| Virginia | Michigan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | P-value | |

| Medicaid | ||||||

| Number of patients | 153 | 157 | 558 | 954 | ||

| Major morbiditya | 23 (15.0)b | 21 (13.4) | 0.68 | 102 (18.3) | 126 (13.2) | 0.008 |

| 30-day mortality | 4 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 0.68 | 14 (2.5) | 15 (1.6) | 0.20 |

| Uninsured | ||||||

| Number of patients | 471 | 402 | 468 | 181 | ||

| Major morbidity | 61 (13.0) | 51 (12.7) | 0.91 | 71 (15.2) | 26 (14.4) | 0.80 |

| 30-day mortality | 8 (1.7) | 10 (2.5) | 0.41 | 5 (1.1) | 6 (3.3) | 0.05 |

| Combined | ||||||

| Number of patients | 624 | 559 | 1026 | 1135 | ||

| Major morbidity | 84 (13.5) | 72 (12.9) | 0.77 | 188 (18.3) | 171 (15.1) | 0.04 |

| 30-day mortality | 12 (1.9) | 13 (2.3) | 0.63 | 19 (1.9) | 21 (1.9) | 1.0 |

Major morbidity includes reoperation, stroke, kidney failure, deep sternal wound infection, and ventilator support > 24 hours within 30 days of operation.

Number (%), all such values

Medicaid Expansion and Outcomes

In a multivariable logistic regression model, era was not associated with unadjusted or adjusted rates of 30-day major morbidity or mortality in all three cohorts in Virginia (Table 5). In Michigan however, post-expansion era was associated with a decreased risk-adjusted rate of postoperative major morbidity (odds ratio [OR], 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.51–0.91; P=0.01). This association between post-expansion era and risk-adjusted major morbidity rates was also observed in the Michigan combined cohort (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77–0.92; P<0.001). Additionally, risk-adjusted mortality increased in Michigan in post-expansion uninsured patients (OR, 3.94; 95% CI, 0.98–15.86; P=0.05) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted post-expansion odds ratios for major morbidity and 30-day mortality

| Virginia | Michigan | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Medicaid | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Major morbiditya | 0.87 (0.46–1.65) | 0.7 | 0.68 (0.52–0.89) | 0.004 |

| 30-day mortalityb | 0.73 (0.16–3.30) | 0.7 | 0.62 (0.30–1.30) | 0.20 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Major morbidity | 0.92 (0.47–1.78) | 0.8 | 0.69 (0.51–0.91) | 0.01 |

| 30-day mortality | 0.63 (0.13–3.02) | 0.6 | 0.61 (0.30–1.27) | 0.19 |

| Uninsured | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Major morbidity | 0.98 (0.66–1.45) | 0.9 | 0.94 (0.58–1.53) | 0.80 |

| 30-day mortality | 1.48 (0.58–3.78) | 0.4 | 3.18 (0.96–10.54) | 0.06 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Major morbidity | 0.97 (0.63–1.51) | 0.9 | 0.83 (0.49–1.42) | 0.50 |

| 30-day mortality | 1.30 (0.48–3.57) | 0.6 | 3.94 (0.98–15.86) | 0.05 |

| Combined | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Major morbidity | 0.92 (0.70–1.22) | 0.6 | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 1.16 (0.62–2.18) | 0.7 | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) | 0.16 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Major morbidity | 0.89 (0.70–1.19) | 0.4 | 0.84 (0.77–0.92) | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 1.02 (0.53–1.98) | 0.9 | 1.10 (0.91–1.32) | 0.35 |

Major morbidity adjusted for predicted risk of morbidity or mortality

Mortality adjusted for predicted risk of mortality.

CI=confidence interval.

COMMENT

When the ACA was signed into law, it included provisions requiring states to expand Medicaid coverage to all Americans with incomes less than 138% of FPL. Prior to the ACA, traditional Medicaid insurance only covered pregnant women, children, and disabled adults, leaving a large number of low income Americans without health insurance. In 2012 however, the federal mandate to expand Medicaid was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and thus the decision fell to individual states. Although federal incentives were provided encouraging Medicaid expansion, only 31 states and the District of Columbia have decided to do so. The financial implications of Medicaid expansion have dominated state government debates and their decisions, with little contemporary data to support or refute the patient benefits of expanding Medicaid.

Using two statewide quality databases, the present study identified a significant benefit of Medicaid expansion in terms of decreased uninsured surgical volume and improved outcomes. In a non-expansion state (Virginia), no differences were identified in terms of uninsured volume, preoperative risk scores, or postoperative morbidity or mortality rates. However, in a state that expanded Medicaid (Michigan), uninsured cardiac surgery volume decreased by 60% over an 18-month period, with a 70% increase in Medicaid-insured volume. Following expansion, Medicaid patients had a significant decrease in postoperative rates of major morbidity after adjusting for preoperative risk.

The observed decrease in uninsured volume in Michigan aligns with predictions that Medicaid expansion under the ACA would lower the number of uninsured people by half.[6] Over the same time period in Virginia, no changes in Medicaid or uninsured volume were identified. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the number of people enrolled in Medicaid is estimated to increase by 12 million people per year between now and 2024.[16] These changes in uninsured and Medicaid volume will have significant effects on hospital reimbursements for uncompensated care under the Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program. Although lower on average than private insurance reimbursement, Medicaid reimbursement is financially more advantageous for hospitals than providing uncompensated care. Under the ACA, DSH payments are being reduced by up to 75%, meaning hospitals will recoup significantly less of the cost for providing care to the uninsured.[6] Within the cardiac surgery population, Medicaid expansion appears to significantly increase the number of insured patients. Additionally, the present study identified a relationship between Medicaid expansion and lower rates of postoperative morbidity, which may also decrease total costs of care. Using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, Ko et al. identified that patients with postoperative complications had higher readmission rates and overall costs of care.[17] When extrapolated to other surgical populations and patient care in general, these changes as a result of Medicaid expansion may have significant financial implications for hospitals.

Aside from monetary benefits, patients may benefit from improvements in preoperative health status. No changes in predicted risk scores were identified in Virginia. However in Michigan, post-expansion Medicaid patients had a significant decrease in PROMM and lower predicted risk of mortality. It is difficult to determine how Medicaid insurance may impact preoperative optimization from the present study, but the findings may reflect increased access to primary care. Using National Health Interview Survey data, Wherry and Miller identified an association between Medicaid expansion and increased health care utilization and more frequent diagnosis of health problems.[28] In a single-state review of Medicaid expansion, Benitez et al. found lower rates of unmet medical needs and fewer people without routine access to healthcare.[19] Proper diagnosis and medical management of comorbidities may result in lower preoperative risk scores.

Surprisingly, no significant differences in the elective/urgent/emergent case status were identified in either state. This lack of difference in Michigan may indicate that changes observed may not reflect increased access to preoperative care, but rather a shift of younger, better-informed, low-risk patients from being uninsured to having Medicaid. This shift in relatively healthy patients subsequently reduces the risk pool in the post-expansion Medicaid population.

If Medicaid expansion does lead to improved preoperative optimization, then an associated improvement in outcomes would be expected. In the current study, post-expansion Medicaid patients in Michigan had significantly lower rates of postoperative morbidity. For healthcare providers, reimbursement rates are important, but not nearly as important as the effect of policy interventions on actual patient outcomes. In Michigan, post-expansion Medicaid patients were 30% less likely to experience a major postoperative complication (adjusted OR, 0.69). In addition to Medicaid insurance reimbursements and higher DSH payments, states that expand Medicaid may see improvements in access to care, preoperative patient optimization, as well as surgical outcomes.

Although the focus was to evaluate the effect of expanding Medicaid, some findings in the uninsured patient population warrant discussion. In Michigan, the uninsured cardiac surgery volume dropped by 60%, while there was no change in Virginia. Of the Michigan patients who were still uninsured after Medicaid expansion, they were older, had a higher PROMM, a higher predicted risk of mortality, and greater 30-day mortality. As Medicaid expansion appears to benefit a significant number of patients, there remains a vulnerable population of uninsured patients who have higher predicted risk scores and rates of morbidity and mortality. An important next step will be to identify patients who did not qualify under traditional Medicaid but gained coverage after expansion and compare them to post-expansion uninsured patients, paying special attention to social determinants of health (i.e. education level, employment status, and housing conditions). This analysis will help determine if the uninsured actually qualify for expanded Medicaid but have barriers to enrollment, or whether they are indeed sicker because they cannot access primary care.

The current study has several limitations. Considering that insurance status is only one factor related to the delivery of healthcare, no definitive or causal relationships between Medicaid expansion and outcomes can be determined; rather, these are inferences that should be used to direct further health policy implementation and research. The dataset did not allow for post-expansion Medicaid patients to be separated based on whether or not they qualified under the traditional system or only after expansion. This study may not reflect changes nationwide, considering it is an analysis of cardiac surgery patients in only two states with differently sized populations. The findings are limited by the relatively short interval of follow-up and lack of complementary percutaneous coronary intervention data. Considering that Medicaid expansion is a fairly recent policy change, repeat analyses will be necessary to validate these findings and assess the impact on patient access to both surgery and interventional cardiology.

Using two statewide databases that collect validated and audited STS cardiac surgery data, the present study identified an association between Medicaid expansion and decreased volume of uninsured cardiac surgery patients, lower preoperative predicted risk scores, and improved postoperative outcomes. Considering that reimbursements for uncompensated care will continue to decline, it appears that Medicaid expansion may improve healthcare financing and positively impact patient care and outcomes. Continuous evaluation of health policy changes such as Medicaid expansion is necessary to expedite advancements in the delivery of high-quality, cost-effective healthcare.

Supplementary Material

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CI

Confidence interval

- DSH

Disproportionate Share Hospital

- FPL

Federal poverty level

- MSTCVS-QC

Michigan Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons Quality Collaborative

- OR

Odds ratio

- PROMM

Predicted risk of morbidity or mortality

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- VCSQI

Virginia Cardiac Services Quality Initiative

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Key Features of the Affordable Care Act by Year. Available at External link http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts-and-features/key-features-of-aca-by-year/index.html. Accessed August 13, 2016.

- 2.Affordable Care Act Eligibility, Medicaid Expansion. Available at External link https://www.medicaid.gov/affordable-care-act/eligibility/index.html. Accessed August 13, 2016.

- 3.A Guide to the Supreme Court’s Decision on the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion. Available at External link https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8347.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2016.

- 4.National Federation of Independent Business et al v Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services, et al. Available at External link http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/11-393c3a2.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2016.

- 5.Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. Available at External link http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed August 15, 2016.

- 6.Graves JA. Medicaid expansion opt-outs and uncompensated care. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2365–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polanco A, Breglio AM, Itagaki S, Goldstone AB, Chikwe J. Does payer status impact clinical outcomes after cardiac surgery? A propensity analysis. Heart Surg Forum. 2012;15(5):E262–7. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20111163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mell MW, Baker LC. Payer status, preoperative surveillance, and rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the US Medicare population. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(6):1378–83. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adepoju L, Wanjiku S, Brown M, et al. Effect of insurance payer status on the surgical treatment of early stage breast cancer: data analysis from a single health system. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):570–2. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boxer LK, Dimick JB, Wainess RM, et al. Payer status is related to differences in access and outcomes of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the United States. Surgery. 2003;134(2):142–5. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapar DJ, Bhamidipati CM, Walters DM, et al. Primary payer status affects outcomes for cardiac valve operations. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(5):759–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaPar DJ, Stukenborg GJ, Guyer RA, et al. Primary payer status is associated with mortality and resource utilization for coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation. 2012;126(11 Suppl 1):S132–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs JP, Shahian DM, Prager RL, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database 2016 Annual Report. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(6):1790–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayanian JZ. Michigan’s approach to Medicaid expansion and reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1773–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virginia Department of Social Services Medicaid Fact Sheet #45. Available at External link https://www.dss.virginia.gov/files/division/bp/medical_assistance/forms/all_other/d032-03-0452-03-eng.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2016.

- 16.Updated Estimates of the Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Available at External link https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/45010-breakout-AppendixB.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2016.

- 17.Lawson EH, Hall BL, Louie R, et al. Association between occurrence of a postoperative complication and readmission: implications for quality improvement and cost savings. Ann Surg. 2013;258(1):10–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828e3ac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early Coverage, Access, Utilization, and Health Effects Associated With the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: A Quasi-experimental Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795–803. doi: 10.7326/M15-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benitez JA, Creel L, Jennings J. Kentucky’s Medicaid Expansion Showing Early Promise On Coverage And Access To Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(3):528–34. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.