Abstract

Magnetic nanoparticles represent a new paradigm for molecular targeting therapy in cancer. However, the transformative targeting potential of magnetic nanoparticles has been stymied by a key obstacle-safe delivery to specified target cells in vivo. As cancer cells grow under nutrient deprivation and hypoxic conditions and decorate cell surface with excessive sialoglycans, sialic acid binding lectins might be suitable for targeting cancer cells in vivo. Here we explore the potential of magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with wheat germ lectin (WGA) conjugate, so-called nanomagnetolectin, as apoptotic targetable agents for prostate cancer. In the presence of magnetic field (magnetofection) for 15 min, 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin significantly promoted apoptosis (~12-fold, p value <0.01) of prostate cancer cells (LNCaP, PC-3, DU-145) compared to normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC, PNT2, PZ-HPV-7), when supplemented with 10 mM sialic acid under nutrient deprived condition. Nanomagnetolectin targets cell-surface glycosylation, particularly sialic acid as nanomagnetolectin induced apoptosis of cancer cells largely diminished (only 2 to 2.5-fold) compared to normal cells. The efficacy of magnetofected nanomagnetolectin was demonstrated in orthotopically xenografted (DU-145) mice, where tumor was not only completely arrested, but also reduced significantly (p value <0.001). This was further corroborated in subcutaneous xenograft model, where nanomagnetolectin in the presence of magnetic field and photothermal heating at ~42 °C induced apoptosis of tumor by ~4-fold compared to tumor section heated at ~42 °C, but without magnetic field. Taken all together, the study demonstrates, for the first time, the utility of nanomagnetolectin as a potential cancer therapeutic.

Keywords: Nanomagnetolectin, Magnetofection, Nanoparticles, Wheat germ agglutinin, Sialic acid, Nutrient deprivation, Cell metabolism, Glycosylation sensing, Metabolic glycoengineering, Apoptosis

1. Introduction

Altered cell-surface glycosylation has long been recognized as distinguishing feature of cancer in general and can be exploited for the new and improved biomarkers and therapeutic options (Pinho and Reis, 2015; Freeze, 2013; Kang et al., 2010; Fuster and Esko, 2005). Sialic acids occupy the terminal position of glycan chains of glycoproteins and glycolipids and contribute to the huge range of glycan structures that mediate cell surface biology. Altered expression of certain sialic acid types or their linkages is closely associated with cancer cellular adhesion, migration and metastasis. The ability to targeting aberrant sialylation in cancer tissues by non-invasive means in vivo would provide tremendous advantages for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Therefore, new approaches for molecular targeting, particularly glycan targeting, are increasingly being used to understand the complexity, diversity and in vivo behaviour of cancers.

Although a variety of approaches for delivering drugs to cancer cells such as delivery of plasmid DNA and siRNA through viral and non-viral vectors are available (Zhao et al., 2016; Wittrup and Lieberman, 2015; Jones et al., 2013), the use of nanotechnology in medicine is rapidly spreading and is being applied to improve diagnosis and therapy of diseases through effective delivery of drugs or imaging agents to target cells at disease sites (Smith et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2010; Park et al., 2010; Petros and DeSimone, 2010). Nanoparticle encapsulated chemotherapeutic drugs have been shown to reduce systemic toxic side effects from generalized systemic distribution. Magnetic drug targeting offers an opportunity to treat malignant tumors loco-regionally without systemic toxicity. The loco-regional cancer treatment with magnetic drug targeting needs several features to be considered: (i) the particles should be of a size that allows sufficient attraction by the magnetic field and their introduction into the tumor or into the vascular system surrounding the tumor; (ii) the magnetic fields should be of sufficient strength to be able to attract the magnetic nanoparticles into the desired area; (iii) the particles complex should deliver and release a sufficient amount of anticancer agents; and (iv) the method of treatment should have good access to the tumor vasculature (Alexiou et al., 2000, 2003, 2006). During past years, nanoparticle-based chemotherapeutics for various cancer and diseases have been approved for clinical use and many more are being studied in clinical trials (Torchilin, 2014; El-Sayed et al., 2006; Min et al., 2015; Barenholz, 2012). In recent years, the efficacy of these nanoparticle-based chemotherapeutics has been further improved by employing magnetic field such that magnetic field holds chemotherapeutic agent at the desired site of activity, thus increasing efficacy and diminishing systemic toxicity (Mura et al., 2013; Park, 2013; Stanley et al., 2012; Ruiz-Hernaández et al., 2011; Hoare et al., 2011).

Going back to the altered glycosylation in cancer cell surface, numerous studies indicated connections between glycosylation and abnormal glucose metabolism associated with most types of cancer (Ohtsubo and Marth, 2006). As cancer cells experience nutrient deprivation and hypoxia during oncogenesis, the resulting metabolic reprogramming, which endows cancer cells with the ability to obtain nutrients during scarcity, constitutes an “Achilles’ heel” that can be exploited by metabolic glycoengineering (MGE) strategies to develop new diagnostic methods and therapeutic approaches (Krambeck et al., 2009; Djansugurova et al., 2012; Badr et al., 2013, 2014). We recently, in vitro, demonstarted that breast cancer cells can efficiently scavenge sialic acid under nutrient deprived condition and decorate cell surface sialoglycans with new epitopes, preferentially with α2,3 linked sialic acid, that can be targeted for diagnostic as well as therapeutic (so called theranostic) applications (Badr et al., 2015a,b, 2016). Therefore, the continued elucidation of lectin–glycan selectivity under specified metabolic conditions is critical step to target cancer-specific glycan alterations. Of a few sialic acid specific lectins that can target cancer sialoglycans, wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) may be suitable as this is obtained from a natural dietary source.

As a first step, we used WGA to target sialoglycans of cancer cells under nutrient deprived condition. We took advantage of the benefit of nanoparticles and magnetic field and prepared, for the first time, magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with the WGA, termed as “nanomagnetolectin”. In this paper, we described the preparation of the nanomagnetolectin and its effect on cancer cell apoptosis in in vitro and in mice xenograft models. Our data suggest that nanomagnetolectin kills cancer cells and completely abolished tumor in mice indicating a potential use of the nanomagnetolectin for cancer therapeutics.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Magnetic nanoparticles (Nano-screen-fluidMAG/B-ARA), Magnetic separator (MagnetoPURE PM-20), Magnetic 96-well format (MagnetoFACTOR-96 plate) and CombiMAG-1000 particles were from Chemicell (Berlin, Germany). Sialic acid (N-acetyl-5-neuraminic-acid, Neu5Ac), was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (San Diego, CA, USA). FITC BrdU Apoptosis Detection Kit was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). FITC-fluorescein conjugated anti-digoxigenin, MES (2-[N-Morpholino] ethanesulfonic acid) and EDC (1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminoproply] carbodiimide) were from Sigma-Aldrich (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mM sodium chloride, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 4.3 mM disodium phosphate, 1.4 mM monopotassium phosphate, pH 7.5) was obtained from Technova (Hollister, CA, 95023 CA USA). Cell culture reagents were from Life Technologies Corporation (San Diego, CA, USA); all other chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Preparation of nanoparticles

2.2.1. Nanoparticles preparation and lectin conjugation

Aliquot of magnatic nanoparticles (50 nM based on Iron oxide Fe3O4) in a 2 ml standard Eppendorf tube was washed twice with 1 ml of coupling buffer MES [0.1 M 2-(N-Morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.0] using magnetic separator (MagnetoPURE PM-20). After discarded MES buffer, freshly prepared of coupling agent EDC (10 mg [1-ethyl-3-(-3-dimethylaminoproply) carbodiimide] in 0.2 ml MES, pH 5.0) was added to the washed particles and vortexed thoroughly for 30 s. WGA lectin (3–10 nM) or its FITC-fluorescein conjugates were coupled to the activated magnatic nanoparticles simultaneously and the resulting suspension was shaken gently for two hours at room temperature. At the end of the incubation time, the uncoupled WGA lectin was removed by washing the particles three times with 1 ml PSB and the WGA lectin conjugated magnetic nanoparticles (so called nanomagentolectin) kept at 4 °C until use. Concentration of lectin in the lectin-nanoparticle conjugate or nanomagnetolectin was determined by the method previously described (Paschkunova-Martic et al., 2005) after correcting the background with unlabeled magnetic nanoparticles. Berifly, three soultions were prepared: Amido Black 10 B dye (100 mg/ml, solution A); mixture of methanol and acetic acid (25:75 v/v, solution B, washing solution); and solution C was 1 M NaOH. The nanomagnetolectin samples were dissolved in 1 ml of deionized water, and mixed intensively with 1 ml of solution A. The mixture was then vortexed for 5 min and centrifuged at 5000×g for 5 min at 0 °C. The pellets were collected and washed several times with solution B before air dry at RT. The dried samples were dissolved in 3 ml of solution C, and determined by UV–vis spectroscopy at 625 nm. To prepare WGA-FITC, FITC solution (1 mg/ml in DMSO) was slowly added to WGA solution (2 mg/ml in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9.0) (50 μl FITC solution per ml of WGA solution) in the dark at 4 °C and the resulting conjugate was separated on a desalting column based on the FITC manufacturer’s instructions.

2.2.2. Nanoparticles size and size distribution

The free nanoparticles and the complexed nanomagnetolectins size and size distribution were determined by laser light scattering with Zeta Potential/Particle Sizer PSS/NICOMP 380 ZLS from Particle Sizing Systems, Inc. (Santa Barbara, CA, USA) at a fixed angle of 90° at 23 °C. In brief, the free nanoparticles and formulated nanomagnetolectin particles were suspended in filtered deionized water and sonicated to prevent particle aggregation and to form uniform dispersion of nanoparticles. The narrow size distribution was given by the polydispersity index. The lower the value is, the narrower the size distribution or the more uniform of the nanoparticles sample. The data represent the average of six measurements.

2.2.3. Nanoparticles surface morphology

Morphology of the formulated nanomagnetolectins was observed by Scanning Electrom Microscopy (SEM), Jeol JSM 5600LV, which requires an ion coating with platinum by a sputter coater (JFC-1300, Jeol, Tokyo) for 30 s in a vacuum at a current intensity of 40 mA after preparing the sample on metallic studs with double-sided conductive tape. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images for these samples were recorded using (TEM; JEM-2100F, Jeol, Tokyo) equipped with a low dose digital camera. The specimen for TEM images was prepared by ultramicrotomy to obtain ultra-thin sections around 70 nm. The powder was embedded in epoxy polaron 612 resin before microtomy.

2.2.4. Nanoparticles surface charge

Zeta potential is an indicator of surface charge, which determines particle stability in dispersion. Zeta potential of nanoparticles was determined by a Zeta Potential/Particle Sizer PSS/NICOMP 380 ZLS from Particle Sizing Systems, Inc. (Santa Barbara, CA, USA) by dipping a palladium electrode in the sonicated particles suspension. The mean value of 6 readings was reported.

2.3. In vitro tumor-targeting studies

2.3.1. Cell culture

Human prostate normal epithelial cells PZ-HPV-7 and prostate cancer cells DU-145, PC-3, LNCaP were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, ML, USA). Human prostate normal epithelial cells PNT-2 and PrEC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Lonza (Walkersville, MD, USA), respectively. Cancer cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (without added antibiotics to avoid sialyltransferase inhibition (Bonay et al., 1996), supplemented with 1% FBS (to minimize the interference degree of BSA sialylation) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

PZ-HPV-7, PNT2 and PrEC cells were cultured in Keratinocyte serum-free medium (without added antibiotics, supplemented with 50 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2.

For all experiments, cells were incubated to reach mid-exponential growth phase, and harvested by treatment with 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer containing 0.54 mM EDTA and 154 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 for <5 min at 37 °C.

2.3.2. Nutrient deprivation and sialic acid treatment

Sialic acid treatment under nutrient deprivation for prostate, normal and cancer cells were performed as previously described (Badr et al., 2013, 2015a,b). Briefly, 104 cells mL−1 aliquots from normal and cancer cell suspension were added in open tubes, containing PBS buffer supplemented with 10 mM sialic acid, in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 with continuous shaking to 2 h of nutrient deprivation duration. Control experiments were additionally employed with cells that maintained in complete medium supplemented with sialic acid.

2.3.3. Cell magnetofection

Magnetofection force was exerted upon WGA lectin associated with magnetic particles to draw the nanomagnetolectin towards target cells. In this manner, the full lectin dose applied gets concentrated on the cells within a few minutes so that the cells get in contact with a significant lectin dose. Using a 96-well microtiter plate, placed upon the MagnetoFACTOR-96 plate, 200 μl of normal or cancer cell-suspension (2.0 × 104) in PBS, were added to each well and let stand for 15 min after its incubation with CombiMAG particles for additional 15 min. The positively residual charges of the CombiMAG particles blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (step-1). Simultaneously, nanomagnetolectin in phosphate buffered saline 100 μl were prepared in parallel row (step-2). The contents of step-2 were mixed with step-1 without re-suspending the cells and the mixtures were incubated at different concentrations or time periods at 37 °C. Cells were separated by centrifugation (1000 rpm, 5 min) and washed twice with 100 μl PBS before finally re-suspended in 1 ml PBS and assayed by flow cytometry. Negative control was similarly except it included unlabeled cells to estimate the auto-fluorescence. Each concentration was tested in triplicate.

2.3.4. TUNEL apoptosis analyses

For the late stage marker of apoptosis measurements, magnetofected cells were incubated with nanomagnetolectin for the indicated times. The cells were fixed in 70% ethanol, washed and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and propidium iodide per the manufacturer’s protocol. The level of fluorescence was used as indicator for the degree of DNA fragmentation.

For detection of apoptosis in tumor sections from both orthotopic or subcutaneous xenografts, the prostate tissue samples were immersed quickly in 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 h followed by overnight immersion in 15% sucrose solution in 1× PBS (500 ml). The tissue samples were embedded into paraffin blocks and 5 μM sections were processed for apoptosis. After dewaxation in xylene, rehydration through graded ethanol in water, digestion using proteinase-K (20 μg/ml) for 15 min, washing in two changes of PBS, and incubation with equilibration buffer for 5 min, TUNEL staining was performed with digoxigenin-dUTP in the presence of working-strength TdT for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min in a humidified chamber at 37 °C. Pure distilled water instead of TdT enzyme was used for negative controls. Stop-wash buffer was used for 10 min to stop the reaction, and FITC conjugated anti-digoxigenin was applied for 30 min with light protection. Slides were visualized using a Leica premium-class modular research manual coded digital inverted microscope for bright field, phase contrast, and simultaneous epifluorescence equipped with full HD digital scientific video camera system. Both the camera and microscope were controlled with Leica Q-FISH software (Leica Microsystems Imaging Solutions). Images were analysed using the Leica MCK-Software package (Leica Microsystems Imaging Solutions).

2.3.5. Flow cytometry

Measurements were carried out using BD FACSAria sorter system (BD Biosciences, USA). Cell-bound fluorescence intensity of the single-cell suspension was determined using a forward versus side scatter gate for the inclusion of single cell populations and exclusion of debris and cell aggregates. Fluorescence was detected at 488 nm blue laser (100 mW) and 532 nm green laser (150 mW). The percentage of positive cells was calculated based on the negative cells staining. Amplification of the fluorescence intensities of individual peaks was adjusted to put the auto-fluorescence signal of unlabeled cells in the first decade of the 5-decade log range. For each measurement 10.000 cells were accumulated.

2.3.6. Magnetofected cell imaging

Cells were stained by incubation of 100 μl cell-suspension (0.7 × 104 cells/ml PBS) with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for 15 min at 37 °C or 42 °C. Magnetofected cells were spun down (1000 rpm, 5 min), washed twice as described above and mounted for microscopy using Lab-Tek 8 chamber Borosilicate cover glass system. Light images of fluorescent labeled cells were obtained using Carl Zeiss Axio Observer (Jena, Germany). Transmission light and fluorescence pictures were acquired at 63 × Oil magnification and excitation were 365 nm, and 470 nm for blue and green respectively. The black level (back-ground offset) of the fluorescence detector was adjusted to eliminate any auto-fluorescence of unstained cells.

2.4. In vivo tumor-targeting studies

2.4.1. Assessment of DU-145 xenograft tumor growth in vivo

To generate DU-145 tumor xenograft, 1 × 107 cells suspended in 50 μl of RPMI-1640 medium containing 60% reconstituted basement membrane (Matrigel; Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA, USA) were injected directly into the prostate right lateral lobe of male BALB/c-nu/nu mice 6 weeks of age (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). Tumor length and width were measured with a digital caliper (Mitutoyo Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and the tumor volume was calculated using the formula: tumor volume = 0.5ab2, where a and b are the larger and smaller diameters, respectively. When the average volume of DU-145 xenograft tumor reached 150 mm3 (day 0), these mice were divided into five groups: group I, control (PBS only); group II, WGA alone; group III, magnetic nanoparticles alone with magnetic field (NPs/+ M); group IV, lectin conjugated magnetic nanoparticles (nanomagnetolectins) without magnetic field (L-NPs/-M); and group V, lectin conjugated magnetic nanoparticles (nanomagnetolectins) with magnetic field (L-NPs/+ M). Each experimental group consisted of five mice. For mice groups NPs/+ M and L-NPs/+ M, an electromagnet with a magnetic flux density of a maximum of 1.2 T from Master Magnetics (Castle Rock, CO, USA) was used to produce a homogeneous magnetic field. The external magnetic field was focused over the tumor during infusion process for 60 min in total. Based on a preliminary experiment of lectin/nanoparticles by intratumoral (data not shown), the optimized dose was determined as 100 μg per mouse. The free lectin and the lectin conjugated magnetic nanoparticles (nanomagnetolectin) (100 μg per mouse) were injected directly into xenograft on day 0, 3 and 6 after mice fasted for 8 h (only drinking water including 10 mM sialic acid). The tumor volume was measured at day 0, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14. At day 14, mice were sacrificed and tumors from each group were collected for further studies. All experiments were performed with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.4.2. In vivo laser photothermal heating

DU-145 (1 × 107 cells) were injected subcutaneously into male BALB/c-nu/nu mice and were allowed to grow until tumors reached 150 mm3 in size. Nanomagnetolectins were intravenously injected into the mice (100 μg per mouse) and irradiated with NIR-light for 30 min, maintaining the average tumor surface temperature at ~42 °C (monitored by infrared thermographic observation) in the presence or absence of magnetofection. After 24 h of nanomagnetolectin injection, mice were sacrificed and TUNEL was performed on the xenografted tumor tissue sections.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between mean values was determined using Welch’s test. Multiple measurement comparisons were carried out by analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni/Dunn test. For the animal study, statistical comparisons were carried out using Fisher’s exact test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical properties of nanoparticles and nanomagnetolectins

3.1.1. Functionalization chemistry and preparation of nanomagnetolectins

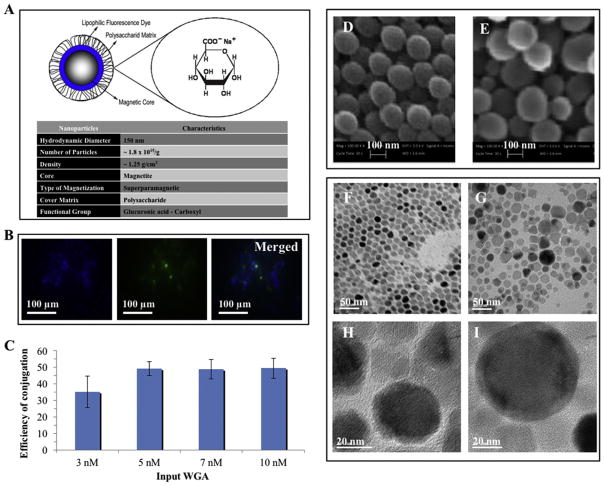

Magnetofluorescent nanoparticles (Nano-screen-fluidMAG/B-ARA) prepared for this study are ferrofluids consisting of an aqueous dispersion of magnetic iron oxides particles with ~200 nm diameter. The particles are covered by three successive layers. The first inner layer is hydrophilic polymers preventing their aggregation by foreign ions, the second medium layer is lipophilic fluorescence Perylen blue dye (excitation of 378 nm & emission of 413 nm) and the third external layer consists of free terminal long arm carboxyl groups destined to covalently bind biomolecules (Fig. 1A). The molar ratio of blue fluorescein dye (BF) to nanoparticles (N) was determined spectrophotometrically and was approximately BF/N = 9.

Fig. 1.

Nanoparticles design and lectin conjugation. (A) Diagram of Nano-screen-fluidMAG/B-ARA a magnetofluorescent nanoparticles consisting of an aqueous dispersion of magnetic iron oxides, lipophilic fluorescence dye and terminal functional carboxyl groups for covalent coupling of designated biomolecules (WGA lectin). (B) Two-color merged confocal fluorescence microscopy images of complex state of nanomagnetolectin; magnetic nanoparticles (50 nM) are depicted in blue and WGA lectin (5 nM) is given in the green panel. (C) Efficiency of WGA conjugation to magnetic nanoparticles. Concentration of WGA lectin in the lectin-nanoparticle conjugate or nanomagnetolectin was determined from the Amido black protein assay and the efficiency of conjugation was calculated based on the input WGA. (D, E) SEM micrographs of the free (D) and WGA conjugated magnetofluorescent (E) nanoparticles. (F–I) TEM micrograph of the free (F, H) and WGA conjugated nanoparticles (G, I) at 50 nm and 20 nm scale bar. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Coupling chemistry of magnetic nanoparticles with carbodiimides as binary covalent binding reaction offered excellent lectin immobilization reproducibility. The carbodiimides reacted with the carboxylate groups from the magnetic beads to highly reactive O-acylisourea derivatives and reacted readily with amino-groups of the WGA or WGA-FITC lectin to formulate so called nanomagnetolectin (Fig. 1B). The efficiency of lectin conjugation to nanoparticles for 3 nM, 5 nM, 7 nM, and 10 nM input WGA was calculated as 35.1%, 49.2%, 48.8%, and 49.5%, respectively (Fig. 1C). So, for the 3 nM, 5 nM, 7 nM, and 10 nM input WGA, the resultant lectin concentration in the WGA-nanoparticle conjugate (nanomagnetolectin) was 1.05 nM, 2.46 nM, 3.42 nM, 4.95 nM, respectively.

In case of WGA-FITC or WGA-FITC nanoparticle conjugate, the molar ratio of green fluorescein (F, for FITC) to WGA lectin (L) was determined spectrophotometrically (by measuring the absorbance at 495 nm for FITC and 280 nm for protein) and was approximately F/L = 3. The molar ratio of fluorescein/nanoparticles (F/N) conjugates was approximately 9.

3.1.2. Size distribution, surface charge, and zeta potential of nanoparticles and nanomagnetolectins

The particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential of the lectin loaded nanoparticles are presented in Table 1. The nanoparticles formulated in this study were found to be in the size range of 200–400 nm. The light scattering measurements of particle size agreed well with the measurement given by the SmileView software from SEM micrographs. Fig. 1D,E show SEM micrographs of the free (D) and WGA conjugated magnetofluorescent (E) nanoparticles. Similar average diameter of the nanoparticles and lectin nanoparticle conjugates were also obtained on TEM micrographs (Fig. 1F–I). The zeta potential was strongly influenced by the lectin used in the surface-grafted process of the nanoparticles. The nanoparticles in the present study were found stable in dispersion state, possessing high absolute values of zeta potential and having negative surface charges.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the free nanoparticles and the nanomagnetolectins.

| Characteristics | Nanoparticles | Nanomagnetolectin |

|---|---|---|

| Size nm (mean ± S.D., n = 6) | 148.8 ± 51.2 nm | 245 ± 64.7 nm |

| Polydispersity | 0.118 | 0.358 |

| Zeta potential mV (mean ± S.D., n = 6) | −35.38 ± 1.12 | −21.78 ± 2.43 |

3.2. Apoptosis of cancer cells with nanomagnetolectins

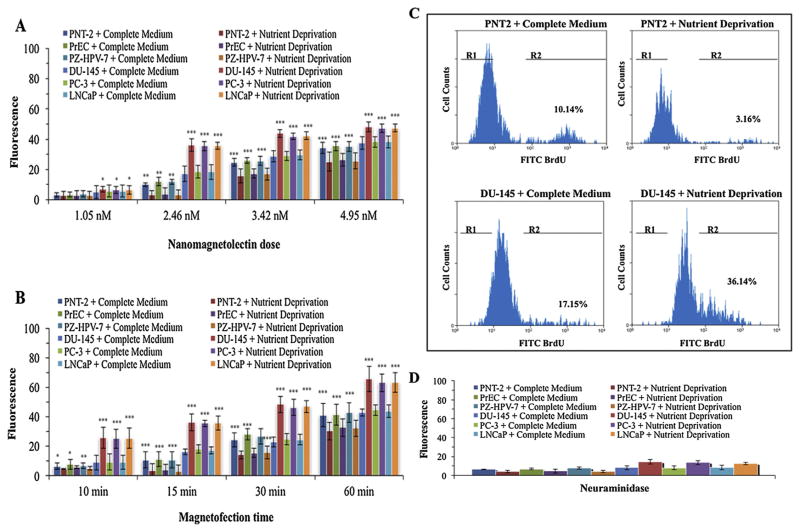

To determine if nanomagnetolectin induces apoptosis of cancer cells, a fixed number of cells (2.0 × 104) were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation and then magnetofected for 15 min with various amount of nanomagnetolectin (1.05, 2.46, 3.42, and 4.95 nM). After fixation and washing steps, the cells were treated with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. The level of fluorescence indicates the degree of DNA fragmentation (increases in late apoptosis). Results showed that there was a dose dependent cell death for both normal (3–4% at 1.05 nM; 3–10% at 2.46 nM; 24–27% at 3.42 nM; and 30–32% at 4.95 nM nanomagnetolectin) and cancer (6–7% at 1.05 nM; 15–35% at 2.46 nM; 28–40% at 3.42 nM; and 34–45% at 4.95 nM nanomagnetolectin) cells (Fig. 2A, see also Supplementary Table 1). However, cell apoptosis between normal and cancer cells at 2.46 nM of nanomagnetolectin, particularly at the nutrient deprived condition, was striking (about 12-fold, p value <0.001). So, we chose this dose for later experiments.

Fig. 2.

Optimization of apoptosis conditions. (A) Detection of late apoptosis. A fixed number of cells were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation or in complete medium and then magnetofected for 15 min with various dose response of nanomagnetolectin. After fixation and washing steps, the cells were treated with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. The level of fluorescence indicates the degree of DNA fragmentation (increases in late apoptosis). The data are representative of three consecutive magnetofection experiments with S.D. indicated by error bars and p values were indicated by asterisk(s). (B) Optimization of magnetofection time conditions. Cells were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation or in complete medium and then magnetofected with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for different time points (10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) followed by treatment with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. The level of fluorescence indicates the degree of DNA fragmentation (increases in late apoptosis). The data are representative of three consecutive magnetofection experiments with S.D. indicated by error bars and p values were indicated by asterisk(s). (C) Flow cytometric diagrams of FITC BrdU apoptotic assays. 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin-mediated apoptosis is enhanced after 2 h of sialic acid treatment under nutrient deprivation as shown by increases in the number of cells staining with anti-BrdU-FITC mAb (R2 gates). The R1 and R2 gates demarcate non-apoptotic and apoptotic populations, respectively. Magnetofected PNT2 normal cells do not incorporate significant amounts of Br-dUTP due to lack of exposed 3′-OH ends, and consequently have relatively little fluorescence compared to DU-145 cancer cells which have an abundance of 3′-OH end. (D) Normal and cancer cell surfaces were pretreated with 10 mM sialic acid under nutrient deprivation or in complete medium, then treated with Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (10 mU/100 μl PBS), washed three times prior to magnetofection with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for 15 min followed by treatment with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. Each experiment was performed with triplicate samples. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

To optimize the magnetofection time conditions, cells (2.0 × 104) were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation and then magnetofected with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for different time points (10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) followed by treatment with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. Results indicated that cell death increased with increase of magnetofection time (Fig. 2B, see also Supplementary Table 2). However, fold difference of apoptosis for cancer cells compared to normal cells was maximum at 15 min – the results were consistent with the previous data (Fig. 2A at 2.46 nM). Fig. 2C shows flow cytometric diagrams of apoptotic cells, PNT2 as a representative of normal cells and DU-145 as a representative of prostate cancer cells at complete medium and nutrient deprived conditions in the presence of 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin with 15 min magnetofection. To determine if nanomagnetolectin targets cancer cell through sialic acid, cells were first incubated with 10 mM sialic acid under nutrient deprivation or in complete medium and then treated with Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (10 mU/100 μl PBS). After washing three times, cells were magnetofected with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for 15 min followed by treatment with a FITC-labeled anti-BrdU mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. Apoptosis of neuraminidase treated cancer cells largely diminished (2–2.5-fold) (Fig. 2D) compared to the untreated cells (see Fig. 2B, 15 min) suggesting that nanomagnetolectin targets cell surface sialic acid. Interestingly, very little or no change of apoptosis was observed in neuraminidase treated normal cells (Fig. 2D) compared to the untreated cells (Fig. 2B, 15 min) suggesting that normal cells are less sensitive to incorporation of additional sialic acid on their surfaces in the presence of 10 mM sialic acid either in complete medium or nutrient deprived condition – results consistent to our previous report (Badr et al., 2015a,b). However, the remaining apoptosis of neuraminidase treated cancer cells by the nanomagnetolectin is probably due to the fact that WGA can still target cancer cells through N-acetylglucosamine as WGA is known to bind both sialic acid and N-acetylglucosamine. Taken together, the results demonstrated the effectiveness of 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for 15 min nanomagnetofection to induce apoptosis of cancer cells compared to normal cells.

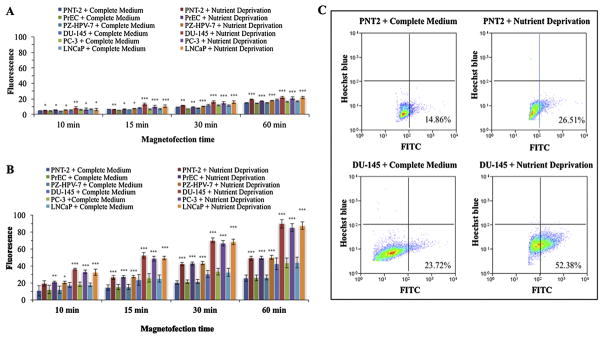

3.3. Cell uptake of nanoparticles and nanomagnetolectins

To determine uptake of free magnetic nanoparticles, a fixed number of cells (2.0 × 104) were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation and then magnetofected with free nanoparticles (50 nM) for different time points (10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) and analyzed by flow cytometry in Hoechst blue filter setting. The level of fluorescence for the cell-bound nanoparticles was detected at 488 nm blue laser (100 mW). Results indicated that the uptake of cells increased (5–20%) over the magnetofection time with the highest at 60 min (Fig. 3A, see also Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Optimization of cellular uptake conditions. (A) Free magnetic nanoparticles uptake. A fixed number of cells were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation or in complete medium and then magnetofected with free nanoparticles (50 nM) for different time points (10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) and analyzed by flow cytometry in Hoechst blue filter setting. The level of fluorescence for the cell-bound nanoparticles was detected at 488 nm blue laser (100 mW). The data are representative of three consecutive magnetofection experiments with S.D. indicated by error bars and p values were indicated by asterisk(s). (B) Complex nanomagnetolectin uptake. A fixed number of cells were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation or in complete medium and then magnetofected with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for different time points (10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) and analyzed by flow cytometry in FITC green filter setting. The level of fluorescence for the cell-bound of nanomagnetolectin complex state was detected at 488 nm blue laser (100 mW) and 532 nm green laser (150 mW). The data are representative of three consecutive magnetofection experiments with S.D. indicated by error bars and p values were indicated by asterisk(s). (C) Flow cytometric diagrams of nanomagnetolectin uptake. Density plot illustrates FITC-positive cells as a function of the nanomagnetolectin uptake. The dot plots are tricolored to indicate the density of the data points; blue indicates a low density, green indicates a medium density and red indicates a high density of points. Each percentage is the mean of triplicate experiments. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In order to determine the uptake of nanomagnetolectin conjugate, cells (2.0 × 104) were treated with 10 mM sialic acid for 2 h under nutrient deprivation and then magnetofected with 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin for different time points (10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min) and analyzed by flow cytometry in FITC green filter setting. The level of fluorescence for the cell-bound of nanomagnetolectin complex state was detected at 488 nm blue laser (100 mW) and 532 nm green laser (150 mW). Results showed that the uptake of the nanomagnetolectin increased over magnetofection time (Fig. 3B, see also Supplementary Table 4) as observed in case of free nanoparticles. However, the uptake of the nanomagnetolectin compared to free nanoparticles was 2–5-fold higher with almost 90% at 60 min. Fig. 3C shows flow cytometric diagrams of nanomagnetolectin uptake in PNT2 as a representative of normal cells and DU-145 as a representative of prostate cancer cells in complete medium and nutrient deprived conditions in the presence of 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin with 15 min magnetofection. Density plot in Fig. 3C illustrates FITC-positive cells as a function of the nanomagnetolectin uptake. Overall, the results indicated 1) higher uptake of nanomagnetolectin compared to free nanoparticles; and 2) higher uptake of nanomagnetolectin by the cancer cells at the nutrient deprived condition compared to the normal cells.

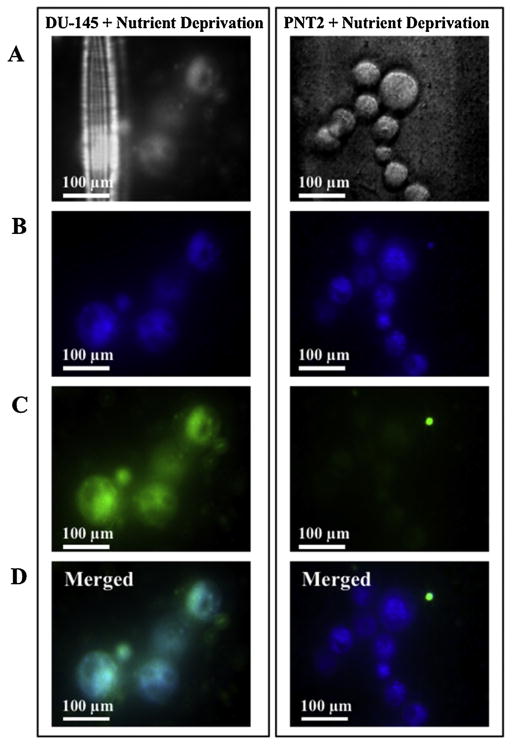

The influence of WGA lectin on cellular penetration of nanomagnetolectin by cancer cells was also confirmed by Laser scanning confocal microscopy (Fig. 4). It was also observed that the internalized lectin nanoparticles did not alter the morphology of cells. Interestingly, from the micrograph images, multiple vesicles containing nanoparticles were observed within the cell cytoplasm. The cytoplasm was not stained uniformly but in a dot like manner indicating the vesicular accumulation of the nanomagnetolectin (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Confocal microscopy images of the PNT2 and DU-145 cells transfected with nanomagnetolectin. Fluorescence images were visualized at 63× Oil magnification and excitation were 365 nm, and 470 nm for blue and green fluorescence respectively. The black level (back-ground offset) of the fluorescence detector was adjusted to eliminate any auto-fluorescence of unstained cells. (A) Phase contrast (non-fluorescence) images of FITC-WGA conjugated magnetofluorescent nanoparticles (Nano-screen-fluidMAG/B-ARA). (B) FITC-WGA conjugated magnetofluorescent nanoparticles (Nano-screen-fluidMAG/B-ARA) showing blue fluorescein Perylen. (C) FITC-WGA conjugated magnetofluorescent nanoparticles (Nano-screen-fluidMAG/B-ARA) showing green FITC. (D) Merged of B and C. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4. In vivo tumor-targeting studies

3.4.1. Magnetofluorescent nanoparticles reduces growth of prostate tumor xenografts

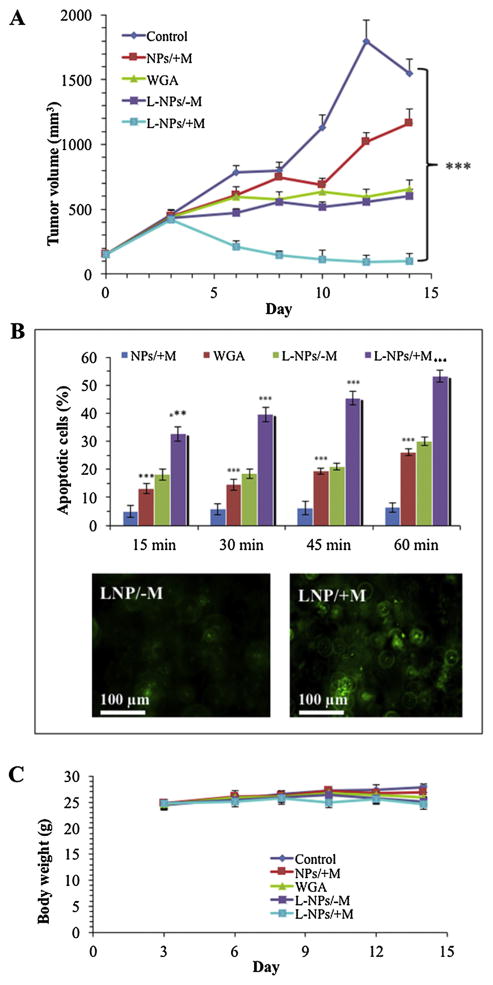

Male BALB/c-nu/nu mice 6 weeks of age bearing DU-145 tumor nodules were treated with nanomagnetolectin or WGA lectin at a dose of 100 μg per mouse 3 times at 0, 3, and 6 days by intratumoral (i.t.) injection. At the end of treatment schedule (Day 14), tumor increased 933% for the untreated control, 670% for mice treated with nanoparticles alone (NPs/+M), and almost 300% for mice treated with WGA alone or nanomagnetolectin without magnetofection (L-NPs/−M) (Fig. 5 A). However, nanomagnetolectin when magnetofected (L-NPs/+M mice group) not only arrested tumor from further growth, but also decreased the size of the tumor from the pre-treatment tumor volume by 33% (data highly significant compared to the untreated control, p value ≤0.001) (Fig. 5A). Overall, WGA alone or nanomagnetolectin without magnetofection (L-NPs/-M) effectively inhibited tumor growth compared to the untreated control, but nanomagnetolectin with magnetofection (L-NPs/+M) had dramatic therapeutic effect against prostate tumor xenograft. Unfortunately, additional control mice group of magnetic nanoparticles alone without magnetofection (NPs/-M) was not enrolled due to the limited number of mice. Nonetheless, the results are justified as the most effective drug i.e. nanomagnetolectin with magnetofection (L-NPs/±M) was validated with two controls such as WGA alone and magnetic nanoparticles alone with magnetofection (NPs/±M).

Fig. 5.

(A) In vivo nanomagnetolectin therapy of DU-145 tumor xenografts in mice. When the average volume of DU-145 xenograft tumors reached 150 mm3 (day 0), mice were divided into five groups: group I, control; group II, magnetic nanoparticles alone with magnetic field (NPs/+ M); group III, WGA; group IV, nanomagnetolectin without magnetic field (L-NPs/-M) and group V, nanomagnetolectin with magnetic field (L-NPs/+ M). The nanomagnetolectin doses were injected directly into the tumor three times (days 0, 3 and 6) after mice fasted for 8 h (only drinking water including 10 mM sialic acid per litter). The results indicate the mean volume ± SE (n = 5). (B) Quantitation of apoptotic cells in prostate tumor tissue sections from treated mice as described in A. The tissue sections were subjected to TUNEL staining with digoxigenin-dUTP in the presence of TdT for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min as described in the Materials and methods 2.3.4. The microscopic images are the representation of TUNEL staining

Cell death of prostate tumor tissue sections was assessed histochemically by TUNEL staining with digoxigenin-dUTP in the presence of working-strength TdT for 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. Quantitation of TUNEL positive cells revealed highest apoptosis (33–53%) with the magnetofected nanomagnetolectin (L-NPs/+M) in all 4 time points TdT incubation (Fig. 5B). Either L-NPs/-M or WGA group of mice showed drastically reduced cell death (13–30%, almost 2-fold less compared to L-NPs/+M) and only magnetofected nanoparticles (NPs/+M) treated mice had the minimum cell death (4–6% only) (Fig. 5B). Average body weight of mice from WGA alone or nanomagnetolectin group (L-NPs/−M and L-NPs/+M) remained same (Fig. 5C). Moreover, mice did not show any sign of stress indicating that the nanomagnetolectin may have less or no toxicity.

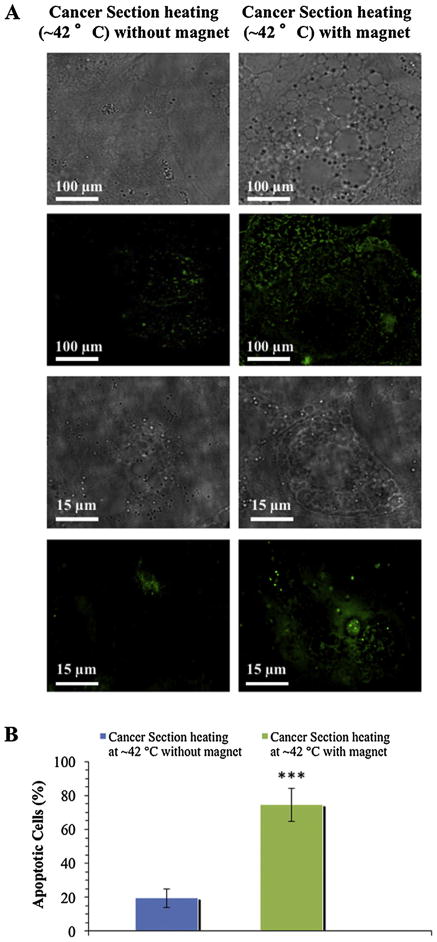

3.4.2. In vivo laser photothermal heating

To determine if single dose of nanomagnetolectin under photothermal heating can promote apoptosis of tumor xenograft, TUNEL assay was performed. Fluorescence image showed enhanced DNA fragmentation in tumor section when heated at ~42 °C in the presence of magnetic field compared to one in absence of magnet (Fig. 6A). Fig. 6B shows the quantitation of apoptotic cells from nanomagnetolectin treated tumor xenograft in the presence of photothermal heating with and without magnetic field and the % of cell death with the magnetofection was almost ~4 times higher (75%) than that without the magnetofection (19.5%).

Fig. 6.

Nanomagnetolectin induced cell death with and without magnetofection after in vivo laser photothermal heating of xenografted tumor at ~42 °C as assessed by TUNEL staining. (A) Phase contrast (top row) and fluorescence images showing enhanced DNA fragmentation (bottom row) in two scales 100 μm and 15 μm. (B) Quantitation of apoptotic cells from nanomagnetolectin treated tumor xeograft in the presence of magnetic field and photothermal heating. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

All cells in nature are covered by a dense and complex array of glycans. Sialic acids occupy the terminal position of glycan chains of glycoproteins and glycolipids and contribute to the huge range of glycan structures that mediate cell surface biology. Changes in glycosylation including sialylated glycans are often a hallmark of cancer disease. In particular, cancer cells frequently display glycans at different levels or with fundamentally different structures than those observed on normal cells. Altered expression of certain sialic acid types or their linkages is closely associated with cancer cellular adhesion, migration and metastasis (Fuster and Esko, 2005). Moreover, differences in cancer cell glycosylation, particularly α2,3-linked sialylation in cancer cells, can be exacerbated by nutrient deprivation combined with supplementation with exogenously-supplied sialic acid (Badr et al., 2015a,b, 2017). This increase in sialylation on the cancer cell surface serves as an epitope for targeting cancer cells with sialic acid binding lectin such as WGA. By taking advantage of unique properties of nanoparticles and nanomagnetofection, we here used a novel conjugate of WGA with magnetic nanoparticles (nanomagnetolectin) under nutrient deprived condition to better target cancer cells. Our overall data (both in vitro and in vivo) demonstrate that nanomagnetolectin, when magnetofected, shows superior activity in promoting apoptosis of cancer cells (free or xenografted) that are treated with sialic acid under nutrient deprivation. Moreover, we optimized the WGA concentration in the nanomagnetolectin and the magnetofection time and found that 2.46 nM nanomagnetolectin with 15 min magnetofection was optimal for the best result (preferential apoptosis of cancer cells compared to normal cells). The critical difference between cancer and normal cell lines was quantitative in nature, with consistently stronger responses to sialic acid supplementation observed in cancer cells (Badr et al., 2015a,b).

Why WGA based nanoparticles? First, WGA is known to bind many cancer cells (Li et al., 2013) and has recently been shown to target cancer cells for the detection (He et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Moreover, WGA exposure has been shown to induce apoptosis of cancer cells through binding to cell surface sialic acids (Schwarz et al., 1999; Gastman et al., 2004). However, when compared the amount of WGA required for ID50 of apoptosis (Schwarz et al., 1999), our nanomagnetolectin is almost 20-times more effective in inducing apoptosis of various prostate cancer cells. This is probably due to the increased cell surface sialylation after sialic acid supplementation of nutrient-deprived cells as evidenced by increased sialyltransferase activity and WGA staining as we have shown in breast cancer cells (Badr et al., 2015a,b). The second reason is that the WGA is a normal dietary constituent in humans and may have less or no toxicity. This is likely true as in our tumor xenograft experiment, average body weight of mice from WGA alone or nanomagnetolectin group (L-NPs/-M and L-NPs/+M) remained same and, also mice did not show any sign of stress. The third, amount of iron oxide of the nanoparticle injected is not toxic. It is mainly metabolized in the hepato-renal system and used in the synthesis of hemoglobin (Weissleder et al., 1989). The fourth, the magnetic fields generated outside are focused on the site of action resulting in enhanced delivery of nanomagnetolectin into the target tumor site.

WGA lectin induced cell death after a short incubation time (15 min) with cancer cells. The mechanism of such accelerated apoptotic effects remains largely unknown. Cancer cells resistant to WGA display reduction in sialic acid and GlcNAc glycan expression indicating that cell surface glycans is crucial for the WGA induced apoptosis (Gastman et al., 2004). It is possible that WGA binds to the sialylated portion of EGFR or other death receptors, leading to their activation and subsequent transduction of the intracellular apoptotic signaling. We previously reported that WGA exerted higher selectivity to glycosylated structures of the human epidermal growth factor receptors overexpressed in nutrient deprived breast cancer cells (Badr et al., 2015a,b). All together, the WGA containing nanomagnetolectin interacts with receptors expressed at the cell surface eventually mimicking the signaling of natural ligands upon binding to their receptors and inducing apoptosis of targeted cancer cells. Regardless of the mechanism, this study for the first time describes the preparation of nanomagnetolectin and its efficacy to preferentially promote apoptosis of cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Dr. Joerg Hoheisel, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (Heidelberg, Germany) for his help with preparation and characterization of the nanomagnetolectin. The studies carried out in the authors’ laboratories have been supported by a grant 0068GF for Scientific Research on Priority Areas Cancer from the Science and Technology Program (Kazakhstan) to LB Djansugurova, and grants R15ES021079-01 from the National Institute of Health (USA), the National Science Foundation (USA) 1334417 to C-Z Li. and grants MII Phase III (TEDCO, Maryland) and R43 CA203420-01 (NCI, NIH) to H.A.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2017.04.005.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

GlycoMantra, Inc. filed a non-provisional full patent entitled “Exploiting nutrient deprivation for modulation of glycosylation – research, diagnostic, therapeutic, and biotechnology applications” on August 16, 2016 with a priority date August 17, 2015. H.A. and H.A.B. are two of the three inventors. There are no other competing financial interests.

References

- Alexiou C, Arnold W, Klein RJ, Parak FG, Hulin P, Bergemann C, Erhardt W, Wagenpfeil S, Lübbe AS. Locoregional cancer treatment with magnetic drug targeting. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6641–6648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd2591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou C, Jurgons R, Schmid RJ, Bergemann C, Henke J, Erhardt W, Huenges E, Parak FG. Magnetic drug targeting—biodistribution of the magnetic carrier and the chemotherapeutic agent mitoxantrone after locoregional cancer treatment. J Drug Target. 2003;11:139–149. doi: 10.1080/1061186031000150791. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/1061186031000150791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou C, Schmid RJ, Jurgons R, Jurgons R, Kremer M, Wanner G, Bergemann C, Huenges E, Nawroth T, Arnold W, Parak FG. Targeting cancer cells: magnetic nanoparticles as drug carriers. Eur Biophys J. 2006;35:446–450. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0042-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00249-006-0042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr HA, Elsayed AI, Ahmed H, Dwek MV, Li C, Djansugurova LB. Preferential lectin binding of cancer cells upon sialic acid treatment under nutrient deprivation. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;171:963–974. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0409-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12010-013-0409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr HA, Alsadek DMM, Darwish AA, Elsayed AI, Bekmanov BO, Khussainova EM, Zhang X, Cho WC, Djansugurova LB, Li CZ. Lectin approaches for glycoproteomics in FDA-approved cancer biomarkers. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2014;11:227–236. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2014.897611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14789450.2014.897611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr HA, AlSadek DMM, Mathew MP, Li CZ, Djansugurova LB, Yarema KJ, Ahmed H. Lectin staining and Western blot data showing differential sialylation of nutrient-deprived cancer cells to sialic acid supplementation. Data Brief. 2015a;5:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.09.043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr HA, AlSadek DMM, Mathew MP, Li CZ, Djansugurova LB, Yarema KJ, Ahmed H. Nutrient-deprived cancer cells preferentially use sialic acid to maintain cell surface glycosylation. Biomaterials. 2015b;70:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr HA, AlSadek DMM, El-Houseini ME, Saeui CT, Mathew MP, Yarema KJ, Ahmed H. Harnessing cancer cell metabolism for theranostic applications using metabolic glycoengineering of sialic acid in breast cancer as a pioneering example. Biomaterials. 2017;116:158–173. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.11.044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barenholz Y. Doxil(R)–the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J Control Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonay P, Munro S, Fresco M, Alacorn B. Intra-Golgi transport inhibition by Megalomicin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3719–3726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.7.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djansugurova L, Badr H, Ahmed H, Khussainova E, Amirgalieva A, Dwek M. Sialic acid treatment makes cancer cells distinguishable from normal cells. FEBS J. 2012;279:315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.08705.x. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed IH, Huang XH, El-Sayed MA. Selective laser photo-thermal therapy of epithelial carcinoma using anti-EGFR antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2006;239:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH. Understanding human glycosylation disorders: biochemistry leads the charge. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6936–6945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.429274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R112.429274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster MM, Esko JD. The sweet and sour of cancer: glycans as novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:526–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc1649. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastman B, Wang K, Han J, Zhen-yu Zhu Huang X, Wang G, Rabinowich H, Gorelik E. A novel apoptotic pathway as defined by lectin cellular initiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Liu F, Liu L, Duan T, Zhang H, Wang Z. Lectin-conjugated Fe2O3@Au core@Shell nanoparticles as dual mode contrast agents for in vivo detection of tumor. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:738–745. doi: 10.1021/mp400456j. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/mp400456j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare T, Timko BP, Santamaria J, Goya GF, Irusta S, Lau S, Stefanescu CF, Lin D, Langer R, Kohane DS. Magnetically triggered nanocomposite membranes: a versatile platform for triggered drug release. Nano Lett. 2011;11:1395–1400. doi: 10.1021/nl200494t. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/nl200494t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CH, Chen CK, Ravikrishnan A, Rane S, Pfeifer BA. Overcoming non viral gene delivery barriers: perspective and future. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:4082–4098. doi: 10.1021/mp400467x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/mp400467x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B, Mackey MA, El-Sayed MA. Nuclear targeting of gold nanoparticles in cancer cells induces DNA damage, causing cytokinesis arrest and apoptosis. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1517–1519. doi: 10.1021/ja9102698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja9102698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krambeck FJ, Bennun SV, Narang S, Choi S, Yarema KJ, Betenbaugh MJ. A mathematical model to derive N-glycan structures and cellular enzyme activities from mass spectrometric data. Glycobiology. 2009;19:1163–1175. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp081. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwp081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Pei Y, Zhang R, Shuai Q, Wang F, Aastrup T, Pei Z. A suspension-cell biosensor for real-time determination of binding kinetics of protein-carbohydrate interactions on cancer cell surfaces. Chem Commun. 2013;49:9908–9910. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45006f. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C3CC45006F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Song S, Shuai Q, Pei Y, Aastrup T, Pei Y, Pei Z. Real-time and label-free analysis of binding thermodynamics of carbohydrate-protein interactions on unfixed cancer cell surfaces using a QCM biosensor. Sci Rep. 2015;15:14066. doi: 10.1038/srep14066. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Y, Caster JM, Eblan MJ, Wang AZ. Clinical translation of nanomedicine. Chem Rev. 2015;115:11147–11190. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater. 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/NMAT3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsubo K, Marth JD. Glycosylation in cellular mechanisms of health and disease. Cell. 2006;126:855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, von Maltzahn G, Ong LL, Centrone A, Hatton TA, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. Cooperative nanoparticles for tumor detection and photothermally triggered drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2010;22:880–885. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902895. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adma.200902895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. Facing the truth about nanotechnology in drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2013;7:7442–7447. doi: 10.1021/nn404501g. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/nn404501g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschkunova-Martic I, Kremser C, Mistlberger K, Shcherbakova N, Dietrich H, Talasz H, Zou Y, Hugl B, Galanski M, Solder E, Pfaller K, Holiner I, Buchberger W, Keppler B, Debbage P. Design, synthesis, physical and chemical characterisation, and biological interactions of lectin-targeted latex nanoparticles bearing Gd–DTPA chelates: an exploration of magnetic resonance molecular imaging (MRMI) Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;123:283–301. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0780-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00418-005-0780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:615–627. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho SS, Reis CA. Glycosylation in cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:540–555. doi: 10.1038/nrc3982. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Hernaández E, Baeza A, Vallet-Regiá M. Smart drug delivery through DNA/magnetic nanoparticle gates. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1259–1266. doi: 10.1021/nn1029229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/nn1029229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz RE, Wojciechowicz DC, Picon AI, Schwarz MA, Paty PB. Wheatgerm agglutinin-mediated toxicity in pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1754–1762. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690593. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Simon JK, Baker JR. Applications of nanotechnology for immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:592–605. doi: 10.1038/nri3488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nri3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SA, Gagner JE, Damanpour S, Yoshida M, Dordick JS, Friedman JM. Radio-wave heating of iron oxide nanoparticles can regulate plasma glucose in mice. Science. 2012;336:604–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1216753. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1216753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin VP. Multifunctional, stimuli-sensitive nanoparticulate systems for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:813–827. doi: 10.1038/nrd4333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissleder R, Stark DD, Engelstad BL, Bacon BR, Compton CC, White DL, Jacobs P, Lewis J. Superparamagnetic iron oxide: pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:167–173. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittrup A, Lieberman J. Knocking down disease: a progress report on siRNA therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:543–552. doi: 10.1038/nrg3978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrg3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, He J, Kang R, Zhao S, Liu L, Li F. RNA interference targeting PSCA suppresses primary tumor growth and metastasis formation of human prostate cancer xenografts in SCID mice. Prostate. 2016;76:184–198. doi: 10.1002/pros.23110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pros.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.