Abstract

Context

While physical function is an important patient outcome, little is known about changes in physical function in older adults receiving chemotherapy (CTX).

Objectives

Identify subgroups of older patients based on changes in their level of physical function; determine which demographic and clinical characteristics were associated with subgroup membership; and determine if these subgroups differed on quality of life (QOL) outcomes.

Methods

Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to identify groups of older oncology patients (n=363) with distinct physical function profiles. Patients were assessed six times over two cycles of CTX using the Physical Component Summary (PCS) score from the SF12. Differences, among the groups, in demographic and clinical characteristics and quality of life (QOL) outcomes were evaluated using parametric and nonparametric tests.

Results

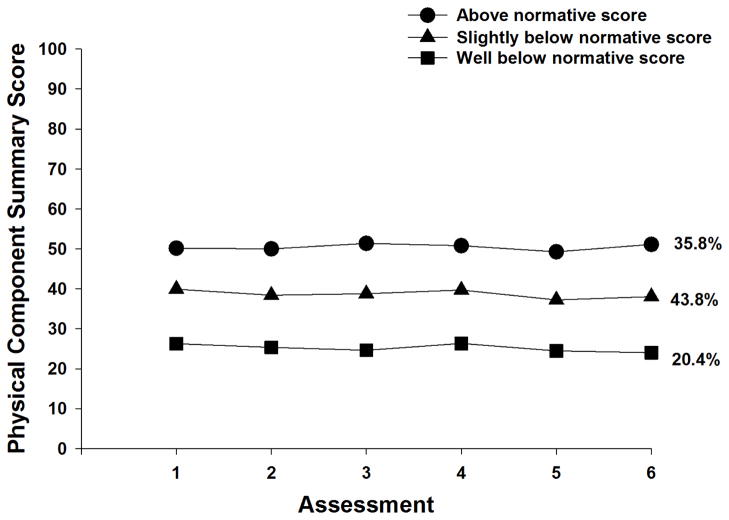

Three groups of older oncology patients with distinct functional profiles were identified: Well Below (20.4%), Below (43.8%), and Above (35.8%) normative PCS scores. Characteristics associated with membership in the Well Below class included: lower annual income, a higher level of comorbidity, being diagnosed with depression and back pain, and lack of regular exercise. Compared to the Above class, patients in the other two classes had significantly poorer QOL outcomes.

Conclusions

Almost 65% of older oncology patients reported significant decrements in physical function that persisted over two cycles of CTX. Clinicians can assess for those characteristics associated with poorer functional status to identify high risk patients and initiate appropriate interventions.

Keywords: physical function, older adults, chemotherapy, comorbidity, latent class analysis

INTRODUCTION

The number of older adults diagnosed with cancer is expected to increase by 67% between 2010 and 2030.1 However, older adults are less likely to receive the most effective cancer treatments2 and to complete a standard course of chemotherapy (CTX).3 To optimize the receipt of cancer treatments in older adults, a significant amount of research has focused on predictors of mortality, dose reductions, and other traditional treatment outcomes (for reviews see 4–7). While prediction of these treatment outcomes is important,8 virtually nothing is known about the impact of CTX on older oncology patients’ functional status during the receipt of CTX.9–12

The assessment of physical function is an extremely important component of any evaluation of the overall health and physiologic reserves of oncology patients. While not assessed as consistently as comorbid conditions, functional status is as important as comorbidity in predicting mortality and health care utilization.13,14 In addition, for many older adults, functional status is an extremely important health outcome that informs treatment decisions.9

After a diagnosis of cancer, regardless of age, patient-reported physical function deteriorates at an accelerated rate compared to that of age-matched controls.4,5,15 However, only two research groups have characterized changes in physical function in older adults receiving cancer treatment, as well as demographic and clinical characteristics associated with functional decline.16–18 In one large prospective study that recruited a sample of newly diagnosed older adults,16,17 changes in physical function were evaluated using the physical functioning subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36).19 In the first report from this study,16 changes in physical function were assessed from prior to the diagnosis of cancer to 6 to 8 weeks after initial treatment. In the second report,17 changes in physical function were evaluated multiple times for up to one year after the cancer diagnosis. In the multivariable analysis, older age and higher number of comorbidities were the only characteristics associated with decreases in physical function in the immediate treatment period.16 In the 12 month follow-up study,17 being female, as well as older age and a higher number of comorbidities were associated with declines in physical function. In the most recent study,18 older adults were evaluated prior to their first and second cycles of chemotherapy (CTX) using a different measure of function, namely the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale.20 In the multivariable model, higher scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale21,22 and lower scores on another measure of function (i.e., Instrumental ADL scale23) at enrollment, were associated with increased risk for functional decline. Across these three studies,16–18 cancer diagnosis, stage of disease, or type of cancer treatment were not associated with either outcome measure. Differences in the functional outcome measures used and the heterogeneous nature of the samples in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics may account for the different predictors that were identified.

While physical function is an extremely important patient outcome,24,25 research on changes in function older oncology patients is extremely scarce. To begin to address this gap, the purposes of this study, in a sample of older oncology outpatients (n=363; ≥65 years of age) whose physical function was assessed using Physical Component Summary (PCS) score from the SF12, six times over two cycles of CTX, were to: identify subgroups of older patients (i.e., latent growth classes) based on changes in their level of self-reported physical function; determine which demographic and clinical characteristics were associated with subgroup membership; and determine if these subgroups differed on quality of life (QOL) outcomes.

METHODS

Patients and Settings

Details regarding the methods for the larger, longitudinal study from which this sample was drawn are published elsewhere.26,27 In brief, for the larger study, eligible patients were ≥18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, gastrointestinal (GI), gynecological (GYN), or lung cancer; had received CTX within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of CTX; were able to read, write, and understand English; and gave written informed consent. Patients were recruited from two Comprehensive Cancer Centers, one Veteran’s Affairs hospital, and four community-based oncology programs. A total of 2234 patients were approached and 1343 consented to participate (60.1% response rate). The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment. For this study, data from patients who were ≥65 years of age (n=363) were used in the analysis of changes in physical function.

Instruments

At enrollment, a demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangements, education, employment status, and income. The Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale was used to assess patients’ overall performance status.28 Patients rated their functional status using the KPS scale that ranged from 30 (I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized) to 100 (I feel normal; I have no complaints or symptoms).29,30

Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) consists of thirteen common medical conditions simplified into language that can be understood without prior medical knowledge.31 Patients indicated if they had the condition; if they received treatment for it (proxy for disease severity); and if it limited their activities (indication of functional limitations). Across the thirteen conditions, the total SCQ score can range from 0 to 39 with higher scores indicating a worse comorbidity profile. The SCQ has well established validity and reliability.32,33

Physical function over the two cycles of CTX was assessed using the PCS score from the SF-12.34 The SF-12 consists of 12 questions about physical and mental health as well as overall health status. The SF-12 was scored into two components that measure physical (i.e., PCS) and psychological (mental component summary (MCS)) function. These scores can range from 0 to 100. Higher PCS and MCS scores indicate better physical and psychological functioning, respectively. The PCS score includes the dimensions of physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health perceptions. The individual items on the SF-12 were used to evaluate generic aspects of QOL. The SF-12 has well established validity and reliability.34

Disease-specific QOL was evaluated using the Quality of Life Scale-Patient Version (QOL-PV)).35,36 This 41-item instrument measures four domains of QOL (i.e., physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being) in oncology patients, as well as a total QOL score. Each item is rated on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale (NRS) with higher scores indicating a better QOL. The QOL-PV has well established validity and reliability.35–38 In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the QOL-PV total score was 0.92.

Study Procedures

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites. Eligible patients were approached by a research staff member in the infusion unit to discuss participation in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Depending on the length of their CTX cycles, patients completed questionnaires in their homes, a total of six times over two cycles of CTX (i.e., prior to CTX administration (i.e., recovery from previous CTX cycle, Assessments 1 and 4), approximately 1 week after CTX administration (i.e., acute symptoms, Assessments 2 and 5), approximately 2 weeks after CTX administration (i.e., potential nadir, Assessments 3 and 6)). Research nurses reviewed patients’ medical records for disease and treatment information.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.39 Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics.

Latent profile analysis (LPA) of physical function scores

As was done for different outcomes,40 unconditional LPA was used to identify the profiles of physical function scores (i.e., PCS scores) that characterized unobserved subgroups of patients (i.e., latent classes) over the six assessments. Typically, growth mixture modeling or latent class growth modeling would be used to identify latent classes of individuals who change differently over time. However, the data in this study demonstrated a complex pattern of change because a pre-treatment assessment, an immediate post-treatment assessment, and a second post-treatment assessment were done over two cycles of CTX. Therefore, LPA is more appropriate for this type of change trajectory. In order to incorporate expected correlations among the repeated measures, we included covariance parameters among measures that were one or two occasions apart (i.e., a covariance structure with a lag of two). In this way, we retained the within person correlation among the measures, at the same time that we focused on the patterns of means that distinguished among the latent classes. We limited the covariance structure to a lag of two to accommodate the expected reduction in correlation that would be introduced by two treatments within each set of three measurement occasions, and to reduce model complexity.

Estimation was carried out with full information maximum likelihood with standard errors and a Chi-square test that are robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations (“estimator=MLR”). Model fit was evaluated to identify the solution that best characterized the observed latent class structure with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLRM), entropy, and latent class percentages that were large enough to be reliable (i.e., likely to replicate in new samples).41,42 Missing data were accommodated with the use of the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm.43

Mixture models, like LPA, are known to produce solutions at local maxima. Therefore, our models were fit with from 1,000 to 2,400 random starts. This approach ensured that the estimated model was replicated many times and was not due to a local maximum. Estimation was done with Mplus Version 7.4.44

Evaluation of differences among the latent classes

Differences among the latent classes in demographic and clinical characteristics and QOL outcomes were evaluated using analysis of variance and Kruskal-Wallis or Chi Square tests with Bonferroni corrected post hoc contrasts. All calculations used actual values. A corrected p-value of <.0167 (i.e., .05/3) was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

LCA of Physical Function

As shown in Table 1, a three class solution was selected because the VLMR was significant, indicating that three classes fit the data better than two classes and the VLMR was not significant for the 4-class solution, indicating that too many classes had been extracted. The classes were named based on a mean reference PCS score of 44.9 identified in the 2001 Utah Health Status Survey as the age based normative score for individuals between 65 to 74 years of age.45 As shown in Figure 1, 35.8% of the sample had PCS scores that were above the normative score at enrollment (i.e., 50.6, “above”). The largest class (43.8%) had PCS scores at enrollment that were slightly below the normative score (i.e., 39.8, “slightly below”). The third class (20.4%) had PCS scores at enrollment that were well below the normative score (i.e., 26.2, “well below”). Across all three classes, the PCS scores remained relatively stable over the two cycles of CTX.

Table 1.

Latent Profile Analysis Solutions and Fit Indices for One- Through Four-Classes for SF-12 Physical Component Scores

| Model | LL | AIC | BIC | VLMR | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Class | −1927.82 | 3897.64 | 3979.42 | n/a | n/a |

| 2 Class | −1800.19 | 3656.37 | 3765.41 | 255.27** | .79 |

| 3 Classa | −1725.57 | 3521.14 | 3657.44 | 149.23* | .82 |

| 4 Class | −1684.82 | 3453.64 | 3617.20 | 81.50ns | .81 |

Not significant;

p < .05;

p < .001

The 3-class solution was selected because the VLMR was significant, indicating that three classes fit the data better than two classes, and the VLMR was not significant for the 4-class solution, indicating that too many classes had been extracted.

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion, BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion, LL = log-likelihood, VLMR = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test for the K vs. K-1 model

Figure 1.

Trajectores of physical component summary function scores for the three physical function latent classes

Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

As shown in Table 2, across the three latent classes, KPS scores (i.e., well below < slightly below < above), as well as number of comorbidities and SCQ scores (i.e., well below > slightly below > above) were in the expected directions. In addition, compared to the above class, patients in the slightly below and well below classes were more likely to be unemployed, to report a lower income, and to have heart disease. Compared to the slightly below and above classes, patients in the well below class were less likely to exercise on a regular basis and more likely to report back pain. Finally, compared to the above class, patients in the well below class had lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and were more likely to report depression.

Table 2.

Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Among the Physical Function Latent Classes

| Characteristic | Well Below Normative Score (0) 20.4% (n=74) |

Below Normative Score (1) 43.8% (n=159) |

Above Normative Score (2) 35.8% (n=130) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 72.7 (6.0) | 71.2 (5.4) | 70.7 (5.4) | F=2.96, p=.053 |

|

| ||||

| Education (years) | 16.6 (3.6) | 16.0 (2.9) | 17.0 (3.1) | F=3.43, p=.034 1 < 2 |

|

| ||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.1 (5.9) | 26.2 (5.1) | 25.5 (5.3) | F=2.09, p=.125 |

|

| ||||

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 68.7 (12.1) | 83.3 (10.6) | 89.6 (8.0) | F=97.22, p<.001 0 < 1< 2 |

|

| ||||

| Number of comorbidities | 3.6 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.3 (1.2) | F=17.01, p<.001 0 > 1 > 2 |

|

| ||||

| SCQ score | 8.2 (3.9) | 6.4 (3.4) | 4.7 (2.4) | F=30.09, p<.001 0 > 1> 2 |

|

| ||||

| Hemoglobin (gm/dl) | 11.1 (1.6) | 11.4 (1.4) | 11.8 (1.3) | F=6.15, p=.002 0 < 2 |

|

| ||||

| Hematocrit (%) | 33.5 (4.7) | 34.2 (4.1) | 35.3 (4.0) | F=4.96, p=.008 0 < 2 |

|

| ||||

| Time since cancer diagnosis (years) | 4.4 (7.9) | 2.4 (4.3) | 2.6 (4.2) | KW, p=.212 |

|

| ||||

| Time since cancer diagnosis (median) | 1.05 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

|

| ||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | 2.0 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.6) | F=1.11, p=.329 |

|

| ||||

| Number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvement | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.1) | F=0.76, p=.471 |

|

| ||||

| Number of metastatic sites excluding lymph node involvement | 1.1 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.8 (0.9) | F=1.71, p=.183 |

|

| ||||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

|

| ||||

| Gender | χ2=6.00, p=.199 | |||

| Female | 78.4 (58) | 67.3 (107) | 63.8 (83) | |

| Male | 21.6 (16) | 32.1 (51) | 36.2 (47) | |

| Transgender* | 0.0 (0) | 0.6 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | χ2=1.48, p=.961 | |||

| White | 80.8 (59) | 78.5 (124) | 81.5 (106) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6.8 (5) | 7.6 (12) | 4.6 (6) | |

| Black | 6.8 (5) | 6.3 (10) | 6.9 (9) | |

| Hispanic, Mixed, or Other | 5.5 (4) | 7.6 (12) | 6.9 (9) | |

|

| ||||

| Married or partnered (% yes) | 58.3 (42) | 55.8 (87) | 63.6 (82) | χ2=1.80, p=.407 |

|

| ||||

| Lives alone (% yes) | 27.8 (20) | 35.5 (55) | 24.0 (31) | χ2=4.59, p=.101 |

|

| ||||

| Child care responsibilities (% yes) | 2.8 (2) | 6.3 (10) | 3.9 (5) | χ2=1.63, p=.442 |

|

| ||||

| Care of adult responsibilities (% yes) | 6.5 (4) | 6.3 (9) | 2.5 (3) | χ 2=2.30, p=.317 |

|

| ||||

| Currently employed (% yes) | 9.6 (7) | 17.6 (28) | 33.9 (43) | χ2=18.90, p<.001 0 and 1 < 2 |

|

| ||||

| Income | KW, p=.002 0 and 1 < 2 |

|||

| < $30,000+ | 31.3 (20) | 25.2 (34) | 18.3 (21) | |

| $30,000 to <$70,000 | 25.0 (16) | 31.1 (42) | 18.3 (21) | |

| $70,000 to < $100,000 | 12.5 (8) | 20.0 (27) | 17.4 (20) | |

| ≥ $100,000 | 31.3 (20) | 23.7 (32) | 46.1 (53) | |

|

| ||||

| Specific comorbidities (% yes) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Heart disease | 17.6 (13) | 15.7 (25) | 3.1 (4) | χ2=14.45, p=.001 0 and 1 > 2 |

|

| ||||

| High blood pressure | 56.8 (42) | 45.9 (73) | 40.0 (52) | χ2=5.33, p=.070 |

|

| ||||

| Lung disease | 31.1 (23) | 22.0 (35) | 11.5 (15) | χ2=11.85, p=.003 0 > 2 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes | 20.3 (15) | 14.5 (23) | 10.8 (14) | χ2=3.47, p=.176 |

|

| ||||

| Ulcer or stomach disease | 4.1 (3) | 5.0 (8) | 3.8 (5) | χ2=0.27, p=.875 |

|

| ||||

| Kidney disease | 1.4 (1) | 3.8 (6) | 0.0 (0) | χ2=5.55, p=.062 |

|

| ||||

| Liver disease | 8.1 (6) | 6.3 (10) | 7.7 (10) | χ2=0.34, p=.845 |

|

| ||||

| Anemia or blood disease | 8.1 (6) | 10.7 (17) | 7.7 (10) | χ2=0.89, p=.642 |

|

| ||||

| Depression | 24.3 (18) | 20.1 (32) | 10.8 (14) | χ2=7.18, p=.028 0 > 2 |

|

| ||||

| Osteoarthritis | 33.8 (25) | 21.4 (34) | 20.0 (26) | χ2=5.64, p=.059 |

|

| ||||

| Back pain | 47.3 (35) | 23.9 (38) | 16.9 (22) | χ2=23.27, p<.001 0 > 1 and 2 |

|

| ||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5.4 (4) | 2.5 (4) | 3.8 (5) | χ2=1.26, p=.532 |

|

| ||||

| Exercise on a regular basis (% yes) | 36.6 (26) | 68.4 (106) | 79.8 (103) | χ2=38.80, p<.001 0 < 1 and 2 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking, current or history of (% yes) | 47.9 (35) | 48.4 (76) | 46.0 (58) | χ2=0.17, p=.920 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Breast | 20.3 (15) | 23.9 (38) | 23.8 (31) | χ2=11.50, p=.074 |

| Gastrointestinal | 20.3 (15) | 35.2 (56) | 36.9 (48) | |

| Gynecological | 28.4 (21) | 18.2 (29) | 22.3 (29) | |

| Lung | 31.1 (23) | 22.6 (36) | 16.9 (22) | |

|

| ||||

| Type of prior cancer treatment | ||||

| No prior treatment | 21.1 (15) | 22.2 (34) | 27.1 (35) | χ2=7.46, p=.280 |

| Only surgery, CTX, or RT | 28.2 (20) | 37.3 (57) | 35.7 (46) | |

| Surgery & CTX, or Surgery & RT, or CTX & RT | 29.6 (21) | 30.1 (46) | 23.3 (30) | |

| Surgery & CTX & RT | 21.1 (15) | 10.5 (16) | 14.0 (18) | |

|

| ||||

| Length of CTX cycle | χ2=2.12, p=.714 | |||

| 14 days | 32.4 (24) | 37.3 (59) | 31.8 (41) | |

| 21 days | 54.1 (40) | 52.5 (83) | 58.9 (76) | |

| 28 days | 13.5 (10) | 10.1 (16) | 9.3 (12) | |

Abbreviations: CTX = chemotherapy, kg = kilograms, KW = Kruskal Wallis; m2 = meter squared, RT = radiation therapy, SCQ = Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire, SD = standard deviation

Chi Square analysis and post hoc contrasts done without the transgender patient include in the analyses

No age or gender differences were found among the latent classes. In addition, none of the disease (i.e., cancer diagnosis, time since cancer diagnosis, number of metastic sites) or treatment (i.e., number of prior cancer treatments, types of prior cancer treatments, CTX cycle length) characteristics were associated with latent class membership.

Differences in Generic QOL Outcomes

As shown in Table 3, for the SF-12 physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, and social functioning scores, the differences among the latent classes followed the same pattern (i.e., well below < slightly below < above). For the role emotional score, compared to patients in the slightly below and above classes, patients in the well below class reported lower scores. In terms of the PCS and MCS scores, the PCS scores followed the expected direction (i.e., well below < slightly below < above). No differences were found among the latent classes in MCS scores.

Table 3.

Differences in Quality of Life Scores at Enrollment Among the Physical Function Latent Classes

| Characteristic | Well Below Normative Score (0) 20.4% (n=74) |

Below Normative Score (1) 43.8% (n=159) |

Above Normative Score (2) 35.8% (n=130) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Medical Outcomes Study – Short Form-12 | ||||

| Physical functioning | 9.6 (15.4) | 42.7 (26.9) | 81.1 (22.6) | F=223.92, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Role physical | 25.2 (19.2) | 46.0 (24.0) | 73.6 (22.3) | F=114.77, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Bodily pain | 55.6 (33.1) | 78.1 (24.7) | 94.0 (13.6) | F=61.24, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| General health | 35.9 (27.8) | 64.8 (23.1) | 75.7 (22.8) | F=63.71, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Vitality | 26.4 (22.6) | 40.5 (25.6) | 62.6 (22.5) | F=58.78, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Social functioning | 43.2 (33.9) | 66.7 (30.6) | 82.0 (25.5) | F=39.56, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Role emotional | 68.7 (34.1) | 72.4 (27.8) | 85.8 (20.8) | F=12.24, p<.001 0 and 1 < 2 |

| Mental health | 73.8 (20.3) | 73.2 (22.0) | 78.5 (17.9) | F=2.69, p=.069 |

| Physical component summary score | 26.2 (6.6) | 39.8 (6.5) | 50.6 (5.9) | F=325.23, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Mental component summary score | 49.9 (11.9) | 49.2 (11.5) | 51.8 (9.3) | F=1.92, p=.148 |

| Quality of Life Scale – Patient Version | ||||

| Physical well-being | 6.0 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.6) | 8.0 (1.3) | F=44.23, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Psychological well-being | 5.0 (1.8) | 5.8 (1.9) | 6.4 (1.8) | F=13.52, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Social well-being | 5.4 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.8) | 7.3 (1.6) | F=25.44, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

| Spiritual well-being | 4.9 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.1) | 4.8 (2.1) | F=0.25, p=.776 |

| Total quality of life score | 5.3 (1.5) | 6.0 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.3) | F=23.04, p<.001 0 < 1 < 2 |

Abbreviation: SD= standard deviation

Differences in Disease-specific QOL Outcomes

As shown in Table 3, for the QOL-PV at enrollment, the physical well-being, psychological well-being, social well-being, and total QOL scores, the differences among the latent classes followed the same pattern (i.e., well below < slightly below < above). No differences were found among the latent classes in the spiritual well-being scores.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to use LPA to identify groups of older oncology patients with distinct physical function profiles over two cycles of CTX. In this relatively large sample of 363 patients, with a mean age of 71.4 (±5.5) years, three groups of older adults with distinct physical function profiles were identified. When the mean PCS scores at enrollment for these three groups were compared to age-based normative data for individuals between 65 to 74 years from the 2001 Utah Health Status Survey (i.e., a mean PCS score of 44.9),45 64.2% of our sample was slightly or well below this normative score. As a validity check, compared to the “above normative score” class, the differences in PCS scores at enrollment for the slightly below (i.e., Cohen’s d = 1.0) and well below (i.e., Cohen’s d = 2.3) classes represent not only statistically significant, but clinically meaningful differences in physical function.46,47 In addition, the PCS scores for the two lower classes were below those reported in studies of older cancer survivors.48,49

It is interesting to note that while previous studies reported a decline in self-reported physical function in the immediate treatment period,16,18 the PCS scores within each of our latent classes remained relatively stable over the two cycles of CTX. One potential explanation for these differences is that mean scores were used in the previous studies to evaluate changes over time. This approach does not allow for the identification of subgroups with distinct physical function profiles. Similar to our findings, Given and colleagues reported that when assessments of average change in physical functioning scores for patients who remained within the same quartile over two assessment were made, these patients scores did not deteriorate over time.17 Additional research is warranted to confirm the latent classes identified in our study.

While consistent with previous reports,16–18 an interesting finding from this study is that none of the cancer or treatment characteristics were associated with latent class membership. Given that metastic disease is associated with decrements in physical function, a reasonable hypothesis would be that older adults in the slightly below and well below classes would have a higher number of metastatic sites and/or would have received a higher number of cancer treatments. Perhaps these patients did not report their functional decline to their oncologists or they were receiving lower doses of CTX compared to those in the above class. Our finding of a lack of an association between cancer burden and functional status warrants confirmation in future studies.

Of note, and consistent with two reports from the same cohort,16,17 both a higher number of comorbid conditions and a more severe comorbidity profile were associated with membership in the two lower physical function classes. In addition, similar to findings from a large epidemiologic study,50 the most common comorbid conditions in this sample were high blood pressure, back pain, osteoarthritis, lung disease, depression, and diabetes. In the current study, the four comorbid conditions that differentiated between the well below and the above normative score classes were: heart disease, lung disease, depression, and back pain. These findings support the need to evaluate not only the number but the impact of specific comorbid conditions on older oncology patients’ functional status as part of a comprehensive geriatric assessment.51–53

Anemia is a common problem in older adults.54,55 Recently, anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level of <12 g/dL in both older men and women.56 Using this definition, not unexpectedly in patients undergoing CTX, all three classes of older patients were anemic. This problem is important to evaluate in older adults because anemia is associated with decreased physical performance,57 an increase in the number of falls,58 frailty,57,59,60 increase in depressive symptoms,61,62 increase in the number of hospitalizations,63 and increased mortality.64,65 While the level of anemia observed in this study may not warrant routine treatment in oncology patients, clinicians need to monitor older adults receiving CTX more carefully to evaluate the impact of anemia on their ability to function.

In terms of demographic characteristics, a higher percentage of older adults in the two lower physical function classes were not employed and reported a lower annual household income. This finding is consistent with work by Owusu and colleagues who found that older women newly diagnosed with nonmetastic breast cancer, who had a median household income of <$35,000 were 2.5 times more likely to have functional disability at the time of their initial diagnosis.66 These findings suggest that financial and social factors warrant evaluation and interventions to mitigate their negative impact on physical function.

Of note, while in the other two classes approximately 70% of the patients reported that they exercised on a regular basis, only 37% of the patients in the well below class indicated this level of exercise. Given that older adults who engage in 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic exercise per week can reduce the risk of functional impairments by 50%,67 clinicians need to assess patients’ level of exercise prior to and during CTX and prescribe exercise interventions.

In terms of generic and disease specific domains of QOL, as shown in Table 3, significant differences were found among the three physical function classes for almost all of the subscales on the SF-12 and the QOL-PV. With the exception of the mental health, MCS, and spiritual well-being subscales, decrements in physical function were associated with lower scores on all domains of QOL. All of the differences in the various QOL subscales represent not only statistically significant but clinicially meaningful decrements in the various QOL domains (i.e., Cohen’s d’s that ranged beween 0.3 and 2.0).46,47 Given the findings from recent interventions studies in older adults and cancer survivors that suggest that physical activity interventions improve patients’ functional status and QOL,68–72 additional research is warranted to evaluate the use of these types of interventions in older adults during CTX. The lack of significant differences among the classes on the mental health and MCS scores may indicate that these items on the SF-12 are not specific enough to capture depressive symptoms.

Several study limitations warrant consideration. Objective measures of physical function were not assessed in this study. However, the PCS score of the SF-12 is a valid and reliable measure of physical function and normative scores are available for comparative purposes. In addition, it is important to note that patients’ self-reported KPS scores, a commonly used measure of functional status in oncology patients, differentiated among the latent classes. Sampling bias may result in an underestimation of the physical function of older adults receiving CTX because patients with lower levels of function may have declined participation. Other measures included in a comprehensive geriatric assessment (e.g., nutritional status, frailty) were not evaluated in this study. Future studies need to compare the latent classes identified in this study to other subgroups identified using other measures of function (e.g., frail versus vulnerable versus fit73) While patients were assessed over two cycles of CTX, an assessment prior to the initiation of the current CTX regimen was not performed. In addition, future studies should determine which components of physical function (i.e., individual items on the SF12) have the most impact on latent class membership.

Despite these limitations, the findings from this study provide new insights into the percentage of older adults receiving CTX who reported decrements in physical function that are below normative values for older adults in the general population. Given the negative impact of comorbidity on physical function observed in our study and other studies,16,17 additional research is warranted on the impact of specific comorbidities and whether optimal management of these comorbidities affects physical function. Future intervention studies to improve physical function in older adults undergoing CTX need to account for demographic, clinical, behavioral, and social characteristics that influence physical function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA134900 and K05CA168960) and the National Institute on Aging (T32AG000212). Dr. Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairfield KM, Murray K, Lucas FL, et al. Completion of adjuvant chemotherapy and use of health services for older women with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3921–3926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2595–603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puts MT, Hardt J, Monette J, et al. Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1133–1163. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puts MT, Santos B, Hardt J, et al. An update on a systematic review of the use of geriatric assessment for older adults in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:307–315. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramjaun A, Nassif MO, Krotneva S, Huang AR, Meguerditchian AN. Improved targeting of cancer care for older patients: a systematic review of the utility of comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurria A, Mohile SG, Dale W. Research priorities in geriatric oncology: addressing the needs of an aging population. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:286–288. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al. Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer. 2008;113:3459–3466. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouliara Z, Kearney N, Stott D, Molassiotis A, Miller M. Perceptions of older people with cancer of information, decision making and treatment: a systematic review of selected literature. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1596–1602. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chouliara Z, Miller M, Stott D, et al. Older people with cancer: perceptions and feelings about information, decision-making and treatment--a pilot study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C, Sia I, Ma HM, et al. The synergistic effect of functional status and comorbidity burden on mortality: a 16-year survival analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JC, Harhay MO, Harhay MN. Patient-reported versus objectively-measured physical function and mortality risk among cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Given B, Given C, Azzouz F, Stommel M. Physical functioning of elderly cancer patients prior to diagnosis and following initial treatment. Nurs Res. 2001;50:222–232. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Given CW, Given B, Azzouz F, Stommel M, Kozachik S. Comparison of changes in physical functioning of elderly patients with new diagnoses of cancer. Med Care. 2000;38:482–493. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoppe S, Rainfray M, Fonck M, et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3877–3882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montorio I, Izal M. The Geriatric Depression Scale: a review of its development and utility. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8:103–112. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA, Brooks JO, 3rd, et al. Proposed factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3:23–28. doi: 10.1017/s1041610291000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, et al. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1187–1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer-Oakes SA, Oye RK, Leake B. Predictors of mortality in older patients following medical intensive care: the importance of functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:862–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Aouizerat B, et al. The symptom phenotype of oncology outpatients remains relatively stable from prior to through 1 week following chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26(3) doi: 10.1111/ecc.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Melisko M, et al. Disease and treatment characteristics do not predict symptom occurrence profiles in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2014;120:2371–2378. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karnofsky D, Abelmann WH, Craver LV, Burchenal JH. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer. 1948;1:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnadig ID, Fromme EK, Loprinzi CL, et al. Patient-physician disagreement regarding performance status is associated with worse survivorship in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2205–2214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ando M, Ando Y, Hasegawa Y, et al. Prognostic value of performance status assessed by patients themselves, nurses, and oncologists in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1634–1639. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner F, Bachmann LM, Weber U, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome 1--the Swiss cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. Identification of candidate categories of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) for a Generic ICF Core Set based on regression modelling. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padilla GV, Presant C, Grant MM, et al. Quality of life index for patients with cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1983;6:117–126. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padilla GV, Ferrell B, Grant MM, Rhiner M. Defining the content domain of quality of life for cancer patients with pain. Cancer Nurs. 1990;13:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrell BR. The impact of pain on quality of life. A decade of research. Nurs Clin North Am. 1995;30:609–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SPSS. IBM SPSS for Windows (Version 23) Armonk, NY: SPSS, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kober KM, Cooper BA, Paul SM, et al. Subgroups of chemotherapy patients with distinct morning and evening fatigue trajectories. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1473–1485. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthen B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 8. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Utah Department of Health. Interpreting the SF-12 - Utah Health Status Survey. Salt Lake City, Utah: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sloan JA, Frost MH, Berzon R, et al. The clinical significance of quality of life assessments in oncology: a summary for clinicians. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:988–998. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osoba D. Interpreting the meaningfulness of changes in health-related quality of life scores: lessons from studies in adults. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;12:132–137. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<132::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Giovannini L, et al. Is long-term cancer survivors’ quality of life comparable to that of the general population? An Italian study Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2663–2668. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang MH, Lytle T, Miller KA, Smith K, Fredrickson K. History of falls, balance performance, and quality of life in older cancer survivors. Gait Posture. 2014;40:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29:41–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlson C, Merel SE, Yukawa M. Geriatric syndromes and geriatric assessment for the generalist. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:263–279. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jolly TA, Deal AM, Nyrop KA, et al. Geriatric assessment-identified deficits in older cancer patients with normal performance status. Oncologist. 2015;20:379–385. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohile SG, Velarde C, Hurria A, et al. Geriatric assessment-guided care processes for older adults: A delphi consensus of geriatric oncology experts. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:1120–1130. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cappellini MD, Motta I. Anemia in Clinical Practice-Definition and Classification: Does Hemoglobin Change With Aging? Semin Hematol. 2015;52:261–269. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rohrig G. Anemia in the frail, elderly patient. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:319–326. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S90727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andres E, Serraj K, Federici L, Vogel T, Kaltenbach G. Anemia in elderly patients: new insight into an old disorder. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13:519–527. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pires Corona L, Drumond Andrade FC, de Oliveira Duarte YA, Lebrao ML. The relationship between anemia, hemoglobin concentration and frailty in Brazilian older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:935–940. doi: 10.1007/s12603-015-0502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dharmarajan TS, Avula S, Norkus EP. Anemia increases risk for falls in hospitalized older adults: an evaluation of falls in 362 hospitalized, ambulatory, long-term care, and community patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:e9–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirani V, Naganathan V, Blyth F, et al. Cross-Sectional and longitudinal associations between anemia and frailty in older Australian men: The concord health and aging in men project. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juarez-Cedillo T, Basurto-Acevedo L, Vega-Garcia S, et al. Prevalence of anemia and its impact on the state of frailty in elderly people living in the community: SADEM study. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:2057–2062. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan WH, Chang YP, Yeh WT, et al. Co-occurrence of anemia, marginal vitamin B6, and folate status and depressive symptoms in older adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25:170–178. doi: 10.1177/0891988712458365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stewart R, Hirani V. Relationship between depressive symptoms, anemia, and iron status in older residents from a national survey population. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:208–213. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182414f7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nguyen HQ, Chu L, Amy Liu IL, et al. Associations between physical activity and 30-day readmission risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:695–705. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201401-017OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirani V, Naganathan V, Blyth F, et al. Multiple, but not traditional risk factors predict mortality in older people: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:9732. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9732-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denewet N, De Breucker S, Luce S, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and comorbidities predict survival in geriatric oncology. Acta Clin Belg. 2016;71:206–213. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2016.1153816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Owusu C, Schluchter M, Koroukian SM, Mazhuvanchery S, Berger NA. Racial disparities in functional disability among older women with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:3839–3846. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Visser M, Simonsick EM, Colbert LH, et al. Type and intensity of activity and risk of mobility limitation: the mediating role of muscle parameters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:762–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daum CW, Cochrane SK, Fitzgerald JD, Johnson L, Buford TW. Exercise interventions for preserving physical function among cancer survivors in middle to late life. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5:214–224. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2016.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hupin D, Roche F, Gremeaux V, et al. Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged >/=60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1262–1267. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morey MC, Blair CK, Sloane R, et al. Group trajectory analysis helps to identify older cancer survivors who benefit from distance-based lifestyle interventions. Cancer. 2015;121:4433–4440. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1883–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith TM, Broomhall CN, Crecelius AR. Physical and psychological effects of a 12-session cancer rehabilitation exercise program. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:653–659. doi: 10.1188/16.CJON.653-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of cancer in the older person: a practical approach. Oncologist. 2000;5:224–237. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-3-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]