Abstract

Advance care planning (ACP) is the process of planning for when individuals are unable to make their own healthcare decisions. Research suggests ACP is understudied among HIV-positive African Americans. We explored ACP knowledge, preferences, and practices with HIV-positive African Americans from an urban HIV-specialty clinic (AFFIRM study). Participants completed surveys and interviews. Descriptive analyses and Poisson regression were conducted on survey data. Qualitative interviews were coded using grounded theory/constant comparative method. Participants were mostly male (55.1%). Half rated their current pain as at least six out of ten (50.8%). Two-thirds had discussed ACP with providers or supporters (66.2%). Qualitative themes were: (1) impact of managing pain on quality of life and healthcare, (2) knowledge/preferences for ACP, and (3) sources of HIV supportive care and coping (N = 39). Correlates of having discussed ACP included: moderate pain intensity (p < 0.10), including supporters in health decisions (p < 0.001), religious attendance (p < 0.05), and knowledge of healthcare mandates (p < 0.01; N = 276). Findings highlight the need for patient education to document healthcare preferences and communication skills development to promote inclusion of caregivers in decision-making.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Advance care planning, End-of-life care, African Americans, Quality of life, Urban health, Mixed methods, DNR

Introduction

Due to advancements in HIV treatment, people living with HIV (PLHIV) are living as long as non-PLHIV, albeit with higher rates of morbidity [1, 2]. Advance care planning (ACP) is the process of communication and planning for when individuals cannot make their own healthcare decisions, which includes documentation of advanced directives and directives, living wills, and/or palliative care to improve quality of life at end of life [3–5]. Given that PLHIV have higher rates of co-morbidities, ACP may be even more crucial among in the population compared to non-infected individuals, particularly as these individuals age [6, 7]. Regardless of HIV status, present research suggests that ACP documentation rates are low among older adults. However, disparities exist in likelihood of ACP among PLHIV, due to factors such as socio-demographics, availability of social support, and engagement in healthcare.

Socio-demographic Factors and ACP

Compared to Whites, African Americans are half as likely to complete ACP documentation, even when they are interested in doing so [8–11]. A systematic review by Sanders and colleagues found that compared to other racial/ethnic groups, African Americans prefer more aggressive care, participate less in ACP, and are most likely to informally discuss ACP and end-of-life care rather than to formally document wishes [12]. Similarly, when African American patients do participate in ACP, they are more likely than other races to have multiple co-morbidities and poorer health status [12]. In addition to African American race, lower socioeconomic status is also associated with lower likelihood of ACP among PLHIV [12–14]. Reasons for this may include less availability of resources for PLHIV in urban and resource-deprived settings and also lower rates of health literacy among low-income African American PLHIV [8–14].

As a result, while these individuals may have access to healthcare, they may not participate in ACP discussions or only do so once their health has deteriorated due to AIDS or other co-morbidities [12–14]. Delayed ACP may be particularly problematic and commonplace for African American PLHIV in resource-deprived urban settings. In Baltimore City, for instance, the vast majority of the adult PLHIV population is low-income and African American [15]. Additionally, Baltimore City is ranked second in the United States in prevalence of injection drug use (IDU), and has limited substance use treatment and harm reduction programs compared to the burden of substance use [15]. Many of these individuals have co-morbid HIV, IDU, and chronic pain conditions such as hyperalgesia due to prolonged substance use [15]. While predictors of ACP remain understudied among all PLHIV [15, 16], factors which encourage ACP are particularly important to identify among low-income African Americans, with co-morbidities such as substance use and chronic pain [12–16].

Social Support and ACP

Social support has long been associated with positive health behaviors [17–20]. Perceived availability of social support, in the form of informal care relationships, has been associated with positive health outcomes among PLHIV, such as HIV viral suppression [17, 18]. Informal care is unpaid support or assistance of persons with serious chronic conditions, usually provided by family or members of the individual’s social network [19, 20]. These relationships may influence the likelihood of ACP planning among low-income African Americans, partly because these individuals may use unpaid care more than other groups. Discussion of ACP and healthcare wishes may occur with informal caregivers, particularly if they provide instrumental assistance to PLHIV such as accompanying them to HIV medical care visits. Additionally, PLHIV are likely to have HIV-positive social support network members, who may have received ACP information from their own HIV care providers or other sources [13, 21–24].

In addition to the impact of informal caregivers on ACP among PLHIV, research also suggests that churches are a source of social support in urban and resource-deprived settings. In urban cities such as Baltimore, churches often have HIV health ministries that may provide social support, such as support groups, and/or informational support in the form of ACP information. Therefore, churches may be a direct link to ACP education because PLHIV may have limited access to ACP information from healthcare providers [25, 26]. More research is needed to explore the role of various forms of social support on ACP discussion, given that African American PLHIV often seek religious support.

Healthcare Engagement and ACP

Findings by Mosack and Wandrey and others suggest that PLHIV look to their healthcare providers for education on healthcare planning, including but not limited to treatment regimens, preventive care, and ACP information [27–30]. Other studies suggest that clinicians often avoid discussion of ACP and end-of-life care entirely, due to lack of training in how to counsel patients [28, 29]. Furthermore, beyond discussion of these factors, rapport and trust in healthcare providers may be crucial to patients’ engagement in care and willingness to discuss and/or document ACP [27–30]. Research to explore the interaction of patients, informal caregivers, and ACP discussion with healthcare providers is currently understudied among PLHIV, particularly those who inject drugs. Given the added complexity of patient-provider racial discordance and the impact of culture on ACP [10–12, 30], research is needed to address this gap.

Synthesis and Purpose

Research suggests that ACP is understudied among health disparate populations, including African American PLHIV [8–11]. Previous studies have identified several possible factors which may impact likelihood of ACP discussion, including socio-demographics [15], availability of social support [17–20], and engagement in healthcare [27–30]. The purpose of the present study was to explore these and other factors related to ACP and end-of-life (EOL) preferences among African American PLHIV. Specifically, we explored: (a) preferences for care at end of life, (b) knowledge of palliative and advance care planning, and (c) factors associated with having discussed ACP with healthcare providers or informal caregivers.

Methods

Study Overview

Data were from baseline of the AFFIRM study, the purpose of which was to examine caregiver, recipient, and social network impact on HIV caregiving, quality of life, treatment goals, and end-of-life care preferences. Inclusion criteria for this study were: (a) age of 18 years or older, (b) documented HIV-seropositive status, and (c) HIV medication use in the prior 30 days. Participants were recruited through community sampling and an HIV-specialty clinic located in Baltimore City, Maryland. Main supporters (social network members who provide informal care) were identified by participants and also invited to participate. Finally, some participants from our previous research study were invited to participate in our initial qualitative interviews (BEACON study). These participants were similarly recruited via community sampling and the HIV-specialty clinic. Inclusion criteria for that study were: (a) age of 18 years or older, (b) documented HIV-seropositive status, (c) HIV medication use in the prior 30 days, and (d) current or former injection drug use [18].

Data Collection

The present research took an exploratory, sequential, connected mixed-methods design [31]. First, data collection consisted of qualitative formative research (exploratory). This informed the design and content of quantitative surveys, which were subsequently conducted with a larger sample of participants (sequential). Qualitative findings guided analyses and contextualized the quantitative arm (connected).

Qualitative Data Collection

The qualitative component of the AFFIRM project consisted of a formative research phase, which informed quantitative data collection, and an exploratory research phase, which was conducted concurrently with survey implementation. In the formative phase, the research team recruited participants from previous studies for qualitative interviews. In the exploratory phase, survey respondents who were highly communicative, or expressed interest in participating in other components of the project, completed both interviews and focus groups. The present study utilized data from main participants only. Written consent was obtained from all participants. The principal investigator and three trained research team members conducted interviews and focus groups, between March 2014 and May 2015, at a research center located off-campus near an academic medical center. Interviews and focus groups lasted between 45 and 120 min. All study procedures were fully approved by the Institutional Review Board which oversees the academic research at the university.

First, interviews and focus groups elicited views about participants’ current health status and the background of their HIV diagnosis (e.g., time since diagnosis, current treatment regimen). Second, we probed participants about their lifetime history with substance use, given that some of these individuals had a known history of injection drug use based on their participation in our previous research, and the prevalence of substance use among African American PLHIV in Baltimore City [15, 18]. Next, we explored care relationships and satisfaction with HIV care. Fourth, we elicited knowledge of ACP topics including advanced directives, living wills, and palliative care, which is care designed to improve quality of life for individuals living with serious chronic illnesses [3, 4].

We also asked participants what they knew about the Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatments (MOLST) because Maryland necessitated completion of the MOLST for all patients discharged to long-term care facilities in 2014 [32]. The MOLST is a form covering options for life-sustaining treatments to be transferred across a patient’s continuum of care. Findings from the formative qualitative phase identified that chronic pain due to HIV and other co-morbid conditions was an emerging theme. Therefore, a key difference between the formative interviews and exploratory focus groups was the probing of chronic pain and pain management with participants, some of whom were recovering from opioid dependence and managing pain using other methods.

Quantitative Data Collection

Participants completed computer-assisted personal interviews with trained interviewers [33]. Participants completed separate written informed consent, even if they had participated in previous interviews and/or focus groups. Similar to the qualitative phase, only main participants’ survey responses were utilized in the present study.

Measures

Dependent variable

The outcome of interest was having ACP discussion. Participants were asked have you ever talked with your: “family or friends about what medical treatments you would want if you were not able to make decisions for yourself?” and “doctor about what medical treatments you would want if you were not able to make decisions for yourself?” Responses were dichotomized, where 0 = never had an ACP discussion versus 1 = have discussed ACP with family, friends, and/or doctors. This dichotomization was directly informed by the qualitative phase, during which several participants identified healthcare providers as their supporters, as opposed to social network members as main supporters.

Independent variables

Predictor variables assessed: (a) socio-demographics: sex, age, health-related quality of life, education, pain intensity, current illicit drug use; (b) social support: religious attendance, inclusion of main supporters in healthcare decisions, care receipt norms; and (c) healthcare engagement: ACP knowledge, preferences, and access, EOL preferences, ACP discussion preference, knowledge of healthcare mandates, and time since last HIV medical care visit).

Sex was categorized as 1 = “Male,” 2 = “Female,” 3 = “Other”. Due to small sample size, individuals who responded as “Other” were excluded (N = 3). Participants reported their age in years. Health-related quality of life was assessed using the Short Form 12 (SF-12) [34]. Items included “How much does your health affect your ability to bend, lift, or squat down?” Responses ranged from “Not at all” to “A lot”. Items 1, 8, 9, and 10 were reverse-scored and summed continuously, where higher scores indicate greater physical functioning [34, 35].

Education was trichotomized [36], where 0 = 8th grade or less/Some high school, 1 = High school diploma or GED, and 2 = Some college or above. Pain intensity was assessed via, “On a scale of 0-10, how would you rate your average level of pain during the past 30 days.10 being the worst possible pain?” Responses were categorized by quartiles, where 0 = 0, 1 = 1 to 5, 2 = 6 to 7, and 3 = 8 to 10 [36]. Current illicit drug use was defined, where 0 = no illicit drug use in the past month versus 1 = use of marijuana, heroin, cocaine, stimulants, and/or injection drugs in the past month.

Religious attendance was assessed via, “How often do you go to religious services?” Responses were categorized such that 0 = Never/Once or twice a year, 1 = Every month/Once or twice a month, and 2 = Every week/More than once a week [ 36]. Inclusion of main supporters in healthcare was assessed via, “How often do you involve _______ in decisions about your medical treatments?” Responses were categorized such that 0 = Never, 1 = Sometimes, 2 = Usually, and 3 = Always [37, 38]. Care receipt norms were assessed with the Caregiving Availability and Acceptance Scale [43–45]; items included “Being helped by family or friends makes me feel dependent on them.” Responses ranged from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree” and were reverse-scored, summed, and trichotomized [36], where 0 = Less comfort with care receipt, 1 = Comfort with care receipt, and 2 = More comfort with care receipt [39–41].

EOL preferences were assessed by questions asking if you could not care for yourself would you prefer to live: (1) “at home with assistance from a home health aide or other healthcare professional;” (2) “at home with assistance from my partner, family, or friends;” and (3) “in a long term care facility such as a nursing home, rather than at home” [ 42, 43]. Responses ranged from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree:” A categorical variable was created, where 0 = Strongly agree/Agree to live at long-term care facility, 1 = Strongly agree/Agree to live at home with home health aide, and 2 = Strongly agree/Agree to live at home with help from friends and family [42, 43].

ACP discussion preference was assessed via, “When do you think is the best time to talk about critical care decisions?” Responses were dichotomized at the median, where 0 = Before getting sick (still healthy) versus 1 = When first diagnosed/First sick/First hospitalized/at end-of-life [42–44]. Knowledge of healthcare mandates was assessed with, “Have you heard of an advance directive or the MOLST form?” Responses were categorized such that 0 = No versus 1 = Yes. HIV medical care visit was assessed via, “When was the last time you had a primary healthcare visit for HIV or AIDS?” Responses were dichotomized at the median, where 0 = Within the past month versus 1 = 1–6 months ago/More than 6 months ago/More than 1 year ago [45].

Data Analyses

Qualitative Analysis

Analyses of qualitative data were conducted first. Interviews and focus groups were professionally transcribed verbatim and coded by three research team members trained in grounded theory constant comparison analyses [31, 46, 47]. Grounded theory is a qualitative approach through which theory is inductively derived, or 'grounded' in social context [47]. This process consists of three sequential phases: (a) open coding, when tentative codes are assigned to textual data; (b) axial coding, to identify possible relationships between codes; and (c) selective coding, where data are distilled into a single theory [47]. The research team met multiple times throughout data collection to ensure that the codebook and codes did not “drift” during analyses, for the purposes of greater reliability and inter-coder consistency. Throughout analyses, at least two coders completed each transcript, met to discuss discrepant codes, and reached consensus coding for each transcript to ensure the validity of findings. Once thematic saturation was reached, interviews were discontinued, the finalized codebook was created, coded text was thematically synthesized, and exemplary quotes were extracted using Atlas.ti 7.0 [48].

Mixed-Methods Integration By Hypothesis Generation

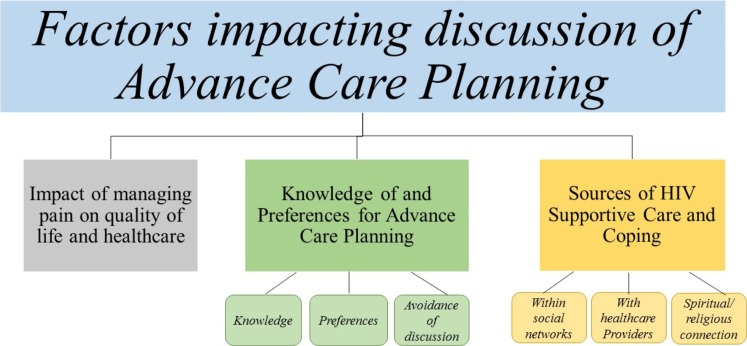

After qualitative analyses were completed, results identified three themes: (1) impact of managing pain on quality of life and healthcare, (2) knowledge of and preferences for advanced care planning, and (3) sources of supportive care and coping. Each of these themes was assessed in statistical analyses, and only variables which were related to qualitative themes were quantitatively assessed.

Quantitative Analyses

Univariate frequencies were generated for outcome and predictor variables on the total sample of main participants (N = 326). Principal component analyses were conducted on the two previously validated scales which assessed health-related quality of life and care receipt norms. One-factor solutions were obtained with good reliability on both scales (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 and 0.70, respectively) [34, 35]. Next, bivariate statistics were calculated. Variables at least marginally significant (p < 0.10) were entered into a multiple Poisson regression model, which are appropriate for binary outcomes for non-rare outcomes (≥10%) [49, 50]. Robust standard errors accounted for inconstant variation (dispersion) in the data [51]. Bivariate and adjusted analyses were only conducted on African American main participants who listed a main supporter (N = 296), due to theoretical significance of the impact of informal caregivers on ACP discussion [17–20].

Age, sex, and health-related quality of life were retained as control variables in the final adjusted model. Finally, a goodness-of-fit test yielded acceptable model fit (Pearson chi-square = 90.0; p > 0.05) [52]. Quantitative analyses were conducted only on complete cases, due to acceptable missingness (under 10%) [53]. All statistical analyses were conducted in STATA Version 14.0 [54].

Results

Participants were mainly male (55.2%), and most had used illicit drugs in the past month (57.8%). Nearly half had less than a high school education (47.9%). Mean age was 52.7 years (standard deviation = 6.2; Table 1). Regarding ACP preferences, most preferred to have ACP discussion before getting sick (54.9%) and had never heard of MOLST or advanced directives (56.2%). The qualitative sample derived from the larger quantitative sample consisted of 39 participants. In-depth interview participants were predominantly male (63.6%; N = 11). Three focus groups were conducted, ranging in size from 8 to 10 participants, and each of which had equal gender breakdown (N = 28).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of African American participants only (N = 315)

| Demographic characteristic | N(%) or Mean SD) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 174 (55.2) |

| Female | 138 (43.8) |

| Other | 3 (1.0) |

| Education level | |

| Less than high school | 151 (47.9) |

| High school diploma/GED | 100 (31.8) |

| Some college or above | 64 (20.3) |

| Illicit drug use (past month) | |

| No | 133 (42.2) |

| Yes | 182 (57.8) |

| Pain intensity in past month | |

| 0 on average | 76 (24.1) |

| 1 to 5 on average | 77 (24.4) |

| 6 to 8 on average | 68 (21.6) |

| 9 to 10 on average | 94 (29.9) |

| Religious attendance | |

| Never/once or twice a year | 94 (29.8) |

| Every month/once or twice a month | 98 (31.1) |

| Every week/more than once a week | 123 (39.1) |

| Identified having a main supporter | |

| No | 28 (8.9) |

| Yes | 287 (91.1) |

| Inclusion of main supporter in medical treatment decisions | |

| Never | 40 (14.0) |

| Sometimes | 102 (35.5) |

| Usually | 44 (15.3) |

| Always | 101 (35.2) |

| Last HIV medical care visit | |

| Within past month | 136 (43.2) |

| 1–6 months ago/6 months or more | 179 (56.8) |

| Care receipt norms | |

| Less comfortable | 95 (30.0) |

| Comfortable | 109 (34.6) |

| More comfortable | 111 (35.2) |

| Care preference if could not care for self (EOL preference) | |

| Live in long-term care facility | 73 (23.9) |

| Live at home with home health aide/with help from family | 232 (76.1) |

| Preference of when to have ACP discussions | |

| Before getting sick, while healthy | 173 (54.9) |

| When first diagnosed/first sick/first hospitalized/at EOL | 142 (45.1) |

| Ever heard of MOLST form or advanced directives | |

| No | 177 (56.2) |

| Yes | 138 (43.8) |

| Health-related quality of life (range: 6–25) | 15.1(4.2) |

| Age in years (range: 24–67) | 52.7(6.3) |

Qualitative Findings

Three qualitative themes emerged from interviews and focus groups (Table 3). The grounded theory which emerged reflected factors which impact whether individuals had ever discussed ACP (Fig. 1), which were then assessed quantitatively. The outcome of interest in quantitative analyses was also directly informed by qualitative findings; ACP discussion with healthcare providers was included because several participants named them as a main source of support.

Table 3.

Qualitative themes and example quotes

| Theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| Impact of managing pain on quality of life and healthcare | “… I’ve been dealing with the neuropathy for years. The pain-- when we talking about pain, I had to have so much-- so much-- I still live with pain, okay? I had-- I’ve been diagnosed with hepatitis…so this is multiple types of pain. I had anemia, I had the sleepless nights, I had the headaches, I had the most severe side effects that you can get, and that’s with the medicines three times… my bone nerve was stripped … I was miserable. I was quarreling. I was begging for mercy. It was just unbelievable…” [Focus Group/Female/63 years old] “…I have to go to Pain Management…I take ten milligrams of oxycodone but I take it as prescribed…They give me enough to last me a month and I take accordingly. That’s the thing about when you go through pain and you talk to your doctor you got to make sure you say on that plan because you can easily fall off if you abuse anything. That’s with anything, food, whatever. You know what I mean? You got to stay on that plan…being ex-addicts we have to learn to adapt to that and watch for that kind of behavior, because we can easily fall…” [Focus Group/Male/53 years old] Substance use history: “... I had the hip surgery. And she wanted that pain medicine like clockwork. But it was so funny the way she did it … we try to remember how we was when we was addicted so we don’t want it.” [Focus group/Female/61 years old] |

| Knowledge of and/or preferences for advanced care planning |

Knowledge: “Well no actually, I have not of those forms, per se. What R_____ was—- he had mentioned it, I am not quite sure if—- now this is just last. This is just in April. So I am assuming that they may have had that form by then, but his family was real adamant, you know. I am not quite sure if he actually had a Maryland MOLST or whatever. What I do know is that there were a lot of friends that were there, but his family he must have discussed this with, because they had let the providers know this was his wish, and they must have had the ammunition...” [Interview/Male/45 years old] “Palliative care? Well I do not really know much about palliative care. I have heard it in our support groups. And actually it’s funny, because that was on one of the discussions, on one of the pamphlets that I was supposed to go to, and I really do not have a clue of what the palliative care is.” [Interview/Male/45 years old] Preferences for ACP and/or EOL: “… I don’t want to tolerate a whole lot of pain, but I do want to make life a lot more-- a quality of life, so that I can continue all the things I enjoy doing, you know, because I belong to committees, I go to. support groups [because] I don’t want nobody to go through what I went through, and I get a chance to learn things…I’m an advocate and an activist [and I want to continue that]…” [Focus Group/Female/63 years old] “I want them if something goes wrong, survive... survive. [If something goes wrong], I want to be resuscitated.[Even if there was no hope], I would tell them, God has the last word.” [Interview/Female/62 years old] “They just need to put me in a nursing home because nobody can be able to take care of me at home... as long as my family came and see me every day... because I do not trust the nursing home to...take care of me as well as my sister’s because they could wash me up.... I would never be cared for in the home. And none of my family or none of my children, nor in my place.” [Interview/Female/59 years old] Avoidance of ACP and/or EOL discussions: “I don’t know. No, not right now. I’ll probably need to, but I’ve not…If I’m diagnosed with cancer or something, active cancer, I would discuss it, you know, my last will and testament and stuff. So I got to do GYN Sunday-- I mean Wednesday. I go back to them and see what they’re going to do about what they found last year and really face it. I didn’t want to face it last year, so I put it off for a whole year after they told me I had cancerous polyps in my anal and in uterus. So I have to deal with that. I put it off for long enough, so it’s something I got to deal with.” [Interview/Female/51 years old] “Because it’s difficult. It’s talking about if something happens to you... I still say it’s no right or wrong way...I’m very sensitive so I know if I started the conversation it would be tears coming out of my eyes so it would be kind of difficult for me to discuss it myself, to start up the conversation.” [Interview/Female/56 years old] |

| Sources of supportive care and coping |

Supportive HIV care relationships with social network: “My youngest daughter, T, she’s very supportive. She knows about my status. She knows about my using and all of that. We have a very good rapport and a good relationship. W’re very close […] my daughter she tries to be there for me when I’m going through something. I can talk to her about my relationship or how I feel, what I’m thinking…” [Interview/Male/56 years old] “…You can be real stacked from the bottom to the top, [but] if the insides it not right you... you living in a lie. Just for the day, I’m medicating with my God, I ask him to keep me and my kids. I have a daughter that’s six years old. She don’t have the virus. She was tested four times, she don’t have to have no meds or nothing, and my [partner]…we were together almost eight years and he don’t have a sign or trace of HIV. I’m just saying that when you’re with somebody, if they love you, they love you because… he didn’t have to lay down with me.I was honest and told him how I was living and what I wanted….[and he was there for me]” [Focus Group/Female/47 years old] “I’m non-detectable when I’m taking my medicines and stuff…[My wife is also HIV-positive], and she’s taking her medicines and stuff now. She’s taking them and everything. But she had gotten to a point where she had fell off from taking them and stuff and she had the real big scare. And you know they, you know, she was like, you know what I mean she was, talking to her, she was really sick, and she was like crying and stuff. Like I think I’m going to die, I’m like you ain’t going nowhere girl. I said Heaven ain’t ready for you and Hell don’t want you. You ain’t going nowhere.” [Interview/Male/55 years old] “...Me and my husband have a therapist and a psychiatrist…we both have to use them because some days is not pretty... But when I get in those moods we stays in …and only come out when we have to come out...So me and my husband we...are not separated. We is one person...” [Interview/Female/36 years old] Supportive HIV care relationships with healthcare providers: “Well, I have a home team, a RN, a CNA, a outpatient therapist and a physical therapist and a social worker through the home team. And my insurance…allowed me to get all the equipment I needed…so I’ve been blessed with that. And through [my insurance] I have a case manager; she’s an RN […] she’s going to be like my sister, she said, while I go through this ordeal.” [Interview/Female/59 years old] “… I’m not saying that these doctors gonna prescribe you what you want, but they better understand what you going through, and [my old doctor] no…He’s caused them to lose a lot of they…[so you have to] find you somebody suitable. ‘Cause I used to have a doctor down there…she was the best HIV medical doctor they had in that building…she was the kind of doctor if you went in there and you said ‘Oh, I don’t feel this, I don’t do that.’ And she asked you ‘Well, what is it you doing?’ And you tell them the wrong thing, she’d be like, ‘Uh-uh.’ No. We not gonna...” [Focus Group/Male/55 years old] Spirituality and religious connections which provide HIV care support: “: I just-- I have my own conscious with God myself. Like a lot of people say they go to church, this and that. I am a Catholic. I don’t attend church on a regular basis, but I read my Bible every day and I understand it for myself. I don’t knock with nobody else to do. I don’t question what they do. It’s not about them, it’s about me and my understanding with God...” [Focus Group/Male/53 years old] “Well… I’ve been living with HIV now since ‘07…. when I started using was 1993. And it’s on dear God’s grace. The choices I made, the decisions I made to do, so I made a decision to live. So I stopped doing all the things, with the help of God. I leaned towards helpless and I went towards people-- having everybody fill me. But I understand this holy knowing through the grace of God and I still go to meetings every now and then when I get a chance to. I go to meetings and I puts it out there about it’s very important to get tested.… And if I didn’t tell people today, they would not know. So a closed mouth not gonna give faith, so I don’t come around thinking that I know everything.” [Focus Group/Female/47 years old] “Yeah...when I was out there using, I stole from them [my siblings] all and they was like, ‘We don’t want nothing to do with you, don’t come around me until you get yourself straight....’So then I got myself straight... I know I’m not going to do that because at the program they teach you to your own self be true. That’s why we have this spiritual basis because we put the word of God into us because every morning we have to be at chapel at seven o’clock, we’ll have a word of encouragement and through the whole day is dealing with recovery and spirituality...” [Interview/Male/51 years old] |

Fig. 1.

Qualitative themes explored in subsequent quantitative analyses (AFFIRM study; N = 39)

Theme 1: Impact of Managing Pain on Quality of Life and Healthcare

Several participants discussed experiencing constant daily pain, sometimes to the point of being bed-ridden. Pain sources identified by participants included intermittent injection drug use (hyperalgesia), and prolonged HIV medication use (peripheral neuropathy). As one focus group participant explained:

“So this is multiple types of pain. ...I had anemia, I had the sleepless nights, I had the headaches, I had the most severe side effects that you can get, and that’s with the medicines three times...You talking about pain, my bone nerve ... was stripped from taking that Tamapovir... I was begging for mercy. It was just unbelievable, the pain, and even today I’ve been cured now for three years… [Focus Group/Female/63 years old]

Participants also discussed how their history of substance such as narcotics impacted their pain management in healthcare visits because they either request not to receive opioids or are denied them:

... I had the hip surgery. And she wanted that pain medicine like clockwork. But it was so funny the way she did it … we try to remember how we was when we was addicted so we don’t want it. [Focus group/Female/61 years old]

Theme 2: Knowledge of and/or Preferences for Advance Care Planning

Across all participants, there was a mix of whether individuals had heard of ACP and related terms, even among those who had recently sought medical care or had loved ones who had recently done so. Very few had heard of palliative care. As one interview participant commented:

Palliative care? I’ve heard it in our support groups…that was on one of the discussions… that I was supposed to go to, and I really don’t have a clue of what the palliative care is. [Interview/Male/45 years old]

Another interview participant, who had heard of the MOLST, explained its use as:

I think I have [heard of MOLST] because it says something along the lines would I prefer or not prefer to be put on life support, be fed by a tube, oxygen. It was a lot of stuff on there. But I think I have [heard of it]. [Interview/Male/56 years old]

While participants displayed varying levels of knowledge of ACP topics, palliative care, EOL topics, and/or MOLST forms, many participants expressed a desire to get all life-sustaining treatments. When probed about preferences for EOL, many participants expressed desire to live as long as possible. One individual, who had heard of and signed a MOLST, stated:

I want them if something goes wrong, survive... survive. [If something goes wrong], I want to be resuscitated.[Even if there was no hope], I would tell them, God has the last word. [Interview/Female/62 years old]

Regarding EOL preferences, the majority of participants stated a preference for living at home and maintaining some independence. However, some individuals had very strong preferences to be in a long-term care facility at end-of-life:

...They just need to put me in a nursing home because nobody can be able to take care of me at home... as long as my family came and see me every day... because I don’t trust the nursing home to...take care of me as well as my sister because they could wash me up... [Interview/Female/59 years old]

Regardless of EOL preferences, most participants mentioned avoiding discussion of preferences, whether their own or those of their loved ones dealing with serious illnesses. Some participants explained that they avoided the topic because it was difficult to articulate their wants for death and dying, or to hear loved ones’ preferences due to fear of losing them:

Because it’s difficult. It’s talking about if something happens to you... I still say it’s no right or wrong way...I’m very sensitive so I know if I started the conversation it would be tears coming out of my eyes so it would be kind of difficult for me to discuss it myself, to start up the conversation. [Interview/Female/56 years old]

Several participants stated that there was no ideal time to have these discussions, particularly because the process may be complicated by competing wishes of family members and/or informal caregivers:

Yeah. My mother and I discussed it... I believe it’s more like business when it comes down to doing advance directives. It’s not about a popularity contest...whether you like it or not…because it comes down to [what] I want. [Interview/Male/45 years old]

Theme 3: Sources of HIV Supportive Care and Coping

Participants discussed three main sources of supportive care and coping, as related to their HIV diagnosis and management: (1) social network of family members, (2) healthcare providers, and (3) spiritual and/or religious connections. Overall, these sources of supportive care represent channels through which ACP discussion may have occurred, as explored in subsequent quantitative analyses.

Many participants stated that they received support from family members, consisting of instrumental assistance (e.g., transportation to doctor’s visits) and emotional support (e.g., coping with stressful events). One focus group participant related how her sister helped her tell others about her HIV diagnosis:

Yes... the first few years... I was in denial... I had met my friend which is now my husband, and I told my sister-- I told my family. So, my sister-- had talked to my sister, and she said tell them, and to see what he say, "just, you have to be honest with him, tell him…So we went outside and I told him…and we’ve been together for like 19 years…. [Focus Group/Female/50 years old]

Participants stated that their supportive care relationships were sometimes strained due to factors such as illness progression. In many cases, reciprocal support was discussed as a means of maintaining the supportive care relationship. One interview participant described how she and her husband manage their HIV care together:

...Me and my husband have a therapist and a psychiatrist…we both have to use them because some days is not pretty... But when I get in those moods we stays in …and only come out when we have to come out...So me and my husband we...are not separated. We is one person... [Interview/Female/36 years old]

Other individuals identified their healthcare providers as their main supporter, mostly receiving informational (e.g., HIV treatment recommendations) and emotional support (e.g., guidance when coping with substance use while managing their HIV diagnosis). As with social network supportive care relationships, participants stated that conflict arose with healthcare providers who were supporters, due to stressors such as recurrent substance use. One interview participant discussed how his healthcare provider helped him overcome addiction:

…When I messed up…He [my provider] didn’t play. He even got to the point and say, ‘If you’re going to do that… I’m not writing no more [prescriptions]-- then die,’ and… I start taking my medicine like I was supposed to and…I got clean because of that. And I had to look at that man loves me more than I love my own self…that’s some powerful stuff. [Interview/Male/53 years old]

Finally, participants discussed spirituality and religion as a global form of coping with their HIV and also as means of coping with day-to-day challenges. Many individuals discussed God in terms of gratitude for issues such as recovering from substance abuse:

Yeah...when I was out there using, I stole from them [my siblings] all and they was like, ‘We don’t want nothing to do with you, don’t come around me until you get yourself straight....’So then I got myself straight... I know I’m not going to do that because at the program they teach you to your own self be true. That’s why we have this spiritual basis because we put the word of God into us because every morning we have to be at chapel at seven o’clock, we’ll have a word of encouragement and through the whole day is dealing with recovery and spirituality... [Interview/Male/51 years old]

Quantitative Findings

Overall, two-thirds of African American individuals with main supporters had discussed ACP previously (66.2%, N = 296; Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlates of having had ACP discussion among African Americans with main supporters only (N = 276)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | CI | AIR | CI | |

| Care receipt norms | ||||

| Comfortable | 1.12 | (0.90, 1.39) | 1.15 | (0.95, 1.40) |

| More comfortable | 1.08 | (0.87, 1.35) | 1.01 | (0.82, 1.25) |

| (ref: Less comfortable) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Pain intensity in past month | ||||

| 0 on average | 1.05 | (0.80, 1.40) | 0.98 | (0.75, 1.30) |

| 6 to 8 on average | 1.38* | (1.08, 1.77) | 1.24ǂ | (0.98, 1.56) |

| 9 to 10 on average | 1.21 | (0.93, 1.56) | 1.04 | (0.83, 1.30) |

| (ref: 1, 5, to on average) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Include main Supp in med decisions | ||||

| Sometimes | 1.59* | (1.04, 2.45) | 1.63* | (1.08, 2.44) |

| Often | 2.06*** | (1.34, 3.17) | 2.01*** | (1.32, 3.05) |

| Always | 2.09*** | (1.38, 3.15) | 1.95*** | (1.32, 2.88) |

| (ref: Never) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Education | ||||

| High school diploma/GED | 0.88 | (0.72, 1.07) | 0.85ǂ | (0.70, 1.02) |

| Some college or above | 0.93 | (0.75, 1.16) | 0.87 | (0.70, 1.08) |

| (ref: up to 8th grade/some HS) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| EOL preference | ||||

| Live in long-term care facility | 1.00 | (0.82, 1.21) | 1.09 | (0.90, 1.33) |

| (ref: Live home with aide/family help) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Religious attendance | ||||

| Every month/once or twice a month | 1.31* | (1.03, 1.66) | 1.30* | (1.04, 1.64) |

| Every week/more than once a week | 1.24ǂ | (0.98, 1.57) | 1.24ǂ | (0.99, 1.55) |

| (ref: Never/once or twice a year) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Preferences for ACP discussion | ||||

| Before getting sick, while healthy | 1.10 | (0.93, 1.30) | 1.17ǂ | (0.99, 1.38) |

| (ref: Diagnosed/sick/In Hospital/EOL) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Last HIV medical care visit | ||||

| Within past month | 0.94 | 1.00 | (0.84, 1.18) | |

| (ref: 1–6 months/6 months or more) | 1.00 | (0.79, 1.11) | 1.00 | |

| Illicit drug use (past month) | ||||

| Yes | 0.97 | (0.83, 1.15) | 1.03 | (0.87, 1.22) |

| (ref: No) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Ever heard of MOLST or Advance directives | ||||

| Yes | 1.36*** | (1.15, 1.60) | 1.35*** | (1.13, 1.60) |

| (ref: No) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 1.34*** | (1.13, 1.58) | 1.14 | (0.97, 1.35) |

| (ref: Females) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age (cont.) | 1.00 | (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 | (0.98, 1.01) |

| Health-related quality of life (cont.) | 1.02ǂ | (1.00, 1.04) | 1.00 | (0.99, 1.03) |

IRR incidence rate ratio, AIR adjusted incidence rate ratio CI 95% confidence interval

ǂMarginally significant p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Correlates of Having Had ACP Discussion

In adjusted analyses, individuals with moderate-to-severe pain intensity in the prior month had a 24% higher likelihood of having discussed ACP, as compared to individuals with low-to-moderate pain intensity (adjusted incidence rate ratio [AIR] = 1.24; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.98, 1.56; p < 0.10). Next, compared to individuals who never included their main supporters in medical treatment decisions, those who did so had twice the likelihood of having discussed ACP (p < 0.01). Next, individuals who attended religious services at least once a month had a 30% higher likelihood of having discussed ACP than individuals who went less often (AIR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.04, 1.64; p < 0.05). Compared to individuals who had never heard of MOLST or advance directives, individuals who had heard of MOLST and/or advance directives had a nearly 40% higher likelihood of having discussed ACP (AIR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.13, 1.60; p < 0.001). Finally, compared to individuals with less than a high school education, individuals with a high school diploma or GED had a 15% lower likelihood of having discussed ACP (AIR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.70, 1.02; p < 0.10).

Discussion

The purpose of the present research was to explore preferences for care at end-of-life, knowledge of palliative and advanced care planning, and factors associated with having discussed ACP with providers or supporters. Our research fills a critical gap in knowledge about the needs of older African Americans living with HIV and other co-morbidities such as substance use and chronic pain. Overall, we found that two-thirds of participants had discussed ACP previously; however, factors associated with having done so differed among individuals. Our study is novel in its mixed-methods design, such that all statistical analyses conducted with the outcome of interest (having discussed ACP) were a direct result of thematic findings from interviews and focus groups. Because the qualitative data collection was formative and exploratory in nature (e.g., hypothesis generating) qualitative themes related to ACP discussion were explored for their potential associations with ACP in quantitative analyses (e.g., hypothesis testing). Furthermore, the qualitative findings directly informed and contextualized the subsequent quantitative data collection, analyses, and interpretation. Therefore, qualitative and quantitative findings regarding factors associated with ACP discussion must be interpreted together, rather than as distinct phases.

First, qualitative analyses revealed that many individuals were unfamiliar with recent healthcare mandates such as the MOLST, even when they had recently accessed HIV or other healthcare. Quantitatively, we found that less than half of respondents had heard of the MOLST and/or advance directives. Furthermore, adjusted regression analyses revealed that those who had heard of the MOLST and/or advance directives had a nearly 40% higher likelihood of having discussed ACP, compared to those who had not heard of them (Table 2). It is possible that, even though these individuals are enrolled in HIV care, their lack of knowledge is due in part to providers who lack training in ACP and therefore do not discuss ACP with their HIV patients [55–57]. Regardless, these findings are supported by previous research, which suggests that African Americans living with serious chronic illnesses are often not educated or counseled about ACP [56–59].

A previous study found that lack of ACP among PLHIV was associated with lower education level [55]. Contrary to that study, we found that higher educational attainment was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of having discussed ACP in quantitative analyses. It is possible that individuals with higher education levels had lower illness severity and therefore perceived less need for discussion of ACP. Future research should assess this relationship among a larger sample of African American PLHIV.

Qualitative analyses also revealed that managing chronic pain often resulted in reduced quality of life among participants and also greatly impacted their healthcare experiences. Previous research has found that PLHIV often live with constant pain due to neuropathy [60–62] and/or co-morbid hyperalgesia due to chronic injection drug use [62]. In adjusted analyses, we found that individuals with moderate-to-severe pain intensity in the prior month had a 24% higher likelihood of having discussed ACP, as individuals with low-to-moderate pain intensity. It is possible that individuals who experienced more severe pain were more likely to discuss ACP with their care providers for several reasons. First, some of the individuals in this study were PLHIV with a history of opioids use, who would have needed to address their chronic pain and other co-morbidities with healthcare providers [12–16]. Consequently, they may have been more likely to receive information on palliative care and/or other ACP-related topics from their providers.

Second, many study participants had chronic pain and were older adults; previous research suggests that while ACP rates are low overall, older adults are more likely to have discussed ACP compared to younger adults [63]. Similarly in the present study, healthcare providers may have been more likely to discuss ACP with older patients than with younger patients. Given that more than half of participants included their main supporters in their healthcare decisions, these main supporters who help participants manage pain may also have provided them with ACP information. Future research should further explore the impact of chronic pain and its potential pathways to ACP discussion among PLHIV.

Next, in adjusted quantitative analyses, we found that individuals who preferred to discuss ACP before getting sick were nearly 20 percent more likely to have discussed ACP as compared to those who preferred to discuss it once already sick. Qualitatively, participants varied in their avoidance of ACP discussions with loved ones.

Nevertheless, even if they had avoided these conversations, the vast majority of participants expressed a strong desire to live a long life. This was the case regardless of their EOL preferences to live at home versus in a long-term care facility. Previous studies suggest that culturally, African Americans prefer aggressive life-sustaining treatment even when there is little chance of benefit [6, 12, 13]. In both interviews and focus groups, we identified a strong desire for life-sustaining treatments and “living as long as possible” among most participants, irrespective of whether they had any prior knowledge of ACP topics or had previously discussed them. Therefore, future research and interventions with this population should educate them on the specific procedures involved with documenting preferences in advanced directives and on MOLST forms. Further, given our findings that main supporters’ inclusion in treatment decisions was highly associated with having discussed ACP, future interventions should include supporters in ACP skill-building.

Finally, our analyses revealed that many study participants utilize social support in the form of spirituality and/or religiousness in their lives. Qualitatively, many individuals discussed God in gratitude for overcoming substance dependence, coping with their HIV diagnosis, and in stating their views on end-of-life preferences (Table 3). Quantitatively, we found that moderate and frequent religious attendance were each associated with a 30% higher likelihood of having discussed ACP (Table 2). Previous studies have documented a view among African Americans of “letting God handle it”, regarding prognosis of their chronic illnesses [25, 26]. Future interventions among African American PLHIV might benefit from direct inclusion of main supporters and/or tailoring ACP education and skill-building with a spiritual context.

Limitations

Several study limitations exist. First, the outcome of interest was very broad in nature (e.g., having ever discussed ACP). Therefore, nuances of how frequently ACP was discussed, or why, were not ascertained. Second, all study data were cross-sectional, which prevents the ascertainment of fluctuations over time. Third, while two qualitative data collection methods were used (focus groups and interviews), the purposive sample used for focus groups was assembled specifically to explore pain-specific themes that were uncovered in the formative interviews. Therefore, comparing and contrasting these methods would merely highlight artificial differences in topics explored and sampling characteristics. Fourth, other correlate covariates could explain additional variance in the quantitative outcome, such as controlling for main supporter involvement in other aspects of participants’ life. Next, running analyses solely among African American main participants may have led to a loss of statistical power to detect significant findings.

Finally, participants in the present analyses were all African American, middle-aged, insured, and in HIV medical care; many also had a history of substance use. Due to the homogeneity of our sample across these characteristics, we did not adjust for several socio-demographic variables (e.g., income, insurance). Thus, while this population is often excluded in research [15, 16], these population characteristics limit the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, the present is one of few studies to contextualize ACP within the African American PLHIV population, who systematically have lower rates of ACP compared to all other racial groups [6, 7]. Our results suggest that ACP skill-building and education are critical for these individuals. Possible avenues of future research and intervention should consider the cultural role of spirituality and religiousness in the experiences of PLHIV. For instance, it may be beneficial to approach and involve local faith leaders in creating culturally appropriate health education materials to increase ACP documentation among African American PLHIV.

Results suggest that healthcare mandates were largely unknown, despite recent healthcare access. Given that African Americans in general have a strong cultural preference for life-sustaining treatments, results underscore the need for education to document preferences and include caregivers in future decision-making [12]. A recent study demonstrated an online patient-centered platform (PREPARE) that provides communication and decision-making training might increase likelihood of ACP among non-white older adults [63]; similarly, implementation of a personal health record tool resulted in increased ACP documentation rates in this population [64].

Recently, Huang and colleagues documented that motivational interviewing techniques increased ACP documentation among African Americans in the south [65]. In their randomized control trial, intervention participants received a one-time 90-min intervention, during which client-centered motivational techniques were used to enhance awareness and engagement with ACP documentation [65]. Future interventions should evaluate this approach among older African Americans in urban settings such as Baltimore City. Given the healthcare-based setting of this intervention, future research should also examine the facilitation of ACP documentation by inclusion of healthcare providers in ACP education. Finally, future interventions should examine the facilitation of ACP documentation by educating healthcare providers. Current research suggests that providers are not educated in these topics and do not discuss them with patients regardless of patient race [56, 57]. Future intervention which incorporates healthcare providers and caregivers could greatly increase ACP in a highly disadvantaged population and improve the ability of these individuals to receive care in line with their wishes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA019413 and R34 DA034314). This research was also supported by the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research (1P30AI094189).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. HIV in the United States: the Stages of Care. 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/2012/Stages-of-CareFactSheet-508.pdf. Accessed 24 November 2016.

- 2.Havlik RJ, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Comorbidities and depression in older adults with HIV. Sex Health. 2011;8:551–559. doi: 10.1071/SH11017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck A, Brown J, Boles M, Barrett M. Completion of advance directives by older health maintenance organization members: the role of attitudes and beliefs regarding life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):300–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Caprariis PJ, Carballo-Dieguez A, Thompson S, et al. Advance directives and HIV: a current trend in the Inner City. J Community Health. 2012;38(3):409–413. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9645-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care . Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. Second Edition. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks JT, Buchacz K, Gebo KA, et al. HIV infection and older Americans: the public health perspective. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):1516–1526. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathai S, Bajillan H, Landay AL, et al. Is HIV a model of accelerated or accentuated aging? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Medi Sci. 2014;69(70):833–842. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist. 2005;45:634–641. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerst K, Burr JA. Planning for end-of-life care: black-white differences in the completion of advance directives. Res Aging. 2008;30(4):428–449. doi: 10.1177/0164027508316618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1953–1958. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krug R, Karus D, Selwyn PA, et al. Late-stage HV/AIDS patients’ and their familial caregivers agreement on the palliative care outcomes scale. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;39:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders JJ, Robinson MT, Block SD. Factors impacting advance care planning among African Americans: results of a systematic integrated review. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(2):202–227. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeong S, Ohr S, Pich J, et al. ‘Planning ahead’ among community-dwelling older people from culturally and linguistically diverse background: a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(1–2):244–255. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farber EW, Marconi VC. Palliative HIV care: opportunities for biomedical and behavioral change. Curr HIV/AIDS Report. 2014;11(4):404–412. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keen L, Khan M, Clifford L, et al. Injection and non-injection drug use and infectious disease in Baltimore City: differences by race. Addict Behav. 2014;39(9):1325–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barocas JA, Erlandson KM, Belzer BK, et al. Advance directives among people living with HIV: room for improvement. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):370–377. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.963019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowlton AR. Informal HIV caregiving in a vulnerable population: toward a network resource framework. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1307–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowlton AR, Yang C, Bohnert A, et al. Main partner factors associated with worse adherence to HAART among women in Baltimore, Maryland: a preliminary study. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1102–1110. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: understanding the health consequences of relationships. 1. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: pathways to health. Physiol Behav. 2003;79(3):409–416. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvan FH, Davis EM, Banks D, et al. HIV stigma and social support among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(5):423–436. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols JE, Speer DC, Watson BJ, et al. Aging with HIV: psychological, social, and health issues. 1. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doull M, O’Connor A, Jacobsen MJ, et al. Investigating the decision-making needs of HIV-positive women in Africa using the Ottawa decision-support framework: knowledge gaps and opportunities for intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(3):279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickard JG, Inoue M, Chadiha LA, et al. The relationship of social support to African American Caregivers’ help-seeking for emotional problems. Soc Serv Rev. 2011;85(2):246–265. doi: 10.1086/660068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalmida SG, Holstad MM, Dilorio C, et al. The meaning and use of spirituality among African American women living with HIV/AIDS. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(6):736–765. doi: 10.1177/0193945912443740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muturi N, An S. HIV/AIDS stigma and religiosity among African American women. J Health Comm. 2010;15(4):388–401. doi: 10.1080/10810731003753125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosack KE, Wandrey RL. Discordance in HIV-positive patient and healthcare provider perspectives on death, dying, and end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(2):161–167. doi: 10.1177/1049909113515068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin CA. Promoting advance directives and ethical wills with the HIV-aging cohort by first assessing clinician knowledge and comfort level. J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care. 2015;26(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamas D, Rosenbaum L. Freedom from the tyranny of choice: teaching the end-of-life conversation. New Eng J Med. 2012;366:1655–1657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaide GB, Pekmezaris R, Nouryan CN, et al. Ethnicity, race, and advance directives in an inpatient palliative care consultation service. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(1):5–11. doi: 10.1017/S1478951512000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maryland MOLST. Medical orders for life-sustaining treatment—Maryland MOLST Order Form.http://marylandmolst.org/pages/molst_form.htm. Accessed 21 November 2016.

- 33.Nova Research Company . Questionnaire development system computer software. Bethesda, MD: Nova Research Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring health. 2. Oxford: New York, NY; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagell P, Westergren A. Measurement properties of the SF-12 health survey in Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2011;1:185–196. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-11026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fong Y. R Statistical Software—Chngpt package for change point logistic regression. http://www.cran.rproject.org/web/packages/chngpt/chngpt.pdf. Accessed 20 November 2016.

- 37.Reinhard SC. Living with mental illness: effects of professional support and personal control on caregiver burden. ResNursHealth. 1994;17(2):79–88. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newsom JT, Nishishiba M, Morgan DL, et al. The relative importance of three domains of positive and negative social exchanges: a longitudinal model with comparable measures. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:746–754. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Aneshensel CS, et al. The structure and functions of AIDS caregiving relationships. Psychosocial Rehabil J. 1994;17:51–67. doi: 10.1037/h0095556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearlin LI, Aneshensel CS, LeBlanc AJ. The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: the case of AIDS caregivers. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(3):223–236. doi: 10.2307/2955368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearlin L, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:2–21. doi: 10.2307/2136319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emanuel LL, et al. Advance directives for medical care: a case for greater use. New Eng J Med. 1991;324:889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103283241305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearlman RA, Starks H, Cain KC, et al. Improvements in advance care planning in the veterans affairs system: results of a multifaceted intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(6):667–674. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straw G, Cummins R. AARP North Carolina end of life care survey. Washington, DC: Knowledge Management; 2003.

- 45.Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, et al. Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: results from the HIV cost and services utilization study. JAMA. 1999;281(24):2305–2315. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasson C, Forman J, Krass D, et al. A qualitative study to understand barriers to implementation of national guidelines for prehospital termination of unsuccessful resuscitation efforts. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14:250–258. doi: 10.3109/10903120903572327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Software S. Atlas.Ti qualitative data analysis and research software for windows, version 7.0. Berlin, DE: Scientific Software; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon RA. Applied statistics for the social and health sciences. 1. New York, NY: Routledge Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Long JS. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables – advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dean C, Lawless JF. Tests for detecting overdispersion in Poisson regression models. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(406):467–472. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1989.10478792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bennett DA. How can I deal with missing data in my study? Austr New Zeal J Public Health. 2001;25:464–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.StataCorp. STATA Statistical Software for Windows, Release 14.0. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

- 55.Sangarlangkarn A, Merlin JS, Tucker RO, Kelley AS. Advanced care planning and HIV infection in the era of antiretroviral therapy: a review. Advanced Care Planning HIV. 2015;23(5):174–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emanuel LL, von Gunten CF, Ferris FD. The education for physicians on end-of-lifecare curriculum. 1999. http://www.ama-assn.org/ethic/epec/download/module_1.pdf. Accessed 24 November 2016.

- 57.Martin CA. Promoting advance directives and ethical wills with the HIV-aging cohort by first assessing clinician knowledge and comfort level. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimmel AL, Wang J, Scott RK, et al. FAmily CEntered (FACE) advance care planning: study design and methods for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for patients with HIV/AIDS and their surrogate decision-makers. Contemporary Clin Trials. 2015;43:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slomka J, Prince-Paul WA, et al. Palliative care, hospice, and advance care planning: views of people living with HIV and other chronic conditions. J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care. 2016;27(4):476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Milligan ED, Mehmert KK, Hinde JL, et al. Thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia produced by intrathecal administration of the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein, gp120. Brain Res. 2000;861(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouhassira D, Attal N, Willer JC, et al. Painful and painless peripheral sensory neuropathies due to HIV infection: a comparison using quantitative sensory evaluation. Pain. 1999;80(1):265–272. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu B, Liu X, Tang SJ. Interactions of opioids and HIV infection in the pathogenesis of chronic pain. Frontiers Microbiol. 2016;7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Aw D, Hayhoe B, Smajdor A, et al. Advance care planning and the older patient. QJM. 2012;105(3):225–230. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bose-Brill S, Kretovics M, Ballenger T, et al. Testing of a tethered personal health record framework for early end-of-life discussions. Am J Managed Care. 2016;22(7):e258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang CH, Crowther M, Allen RS, et al. A pilot feasibility intervention to increase advance care planning among African Americans in the deep south. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(2):164–173. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]