Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that police victimization is widespread in the USA and psychologically impactful. We hypothesized that civilian-reported police victimization, particularly assaultive victimization (i.e., physical/sexual), would be associated with a greater prevalence of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Data were drawn from the Survey of Police-Public Encounters, a population-based survey of adults (N = 1615) residing in four US cities. Surveys assessed lifetime exposure to police victimization based on the World Health Organization domains of violence (i.e., physical, sexual, psychological, and neglect), using the Police Practices Inventory. Logistic regression models tested for associations between police victimization and (1) past 12-month suicide attempts and (2) past 12-month suicidal ideation, adjusted for demographic factors (i.e., gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, income), crime involvement, past intimate partner and sexual victimization exposure, and lifetime mental illness. Police victimization was associated with suicide attempts but not suicidal ideation in adjusted analyses. Specifically, odds of attempts were greatly increased for respondents reporting assaultive forms of victimization, including physical victimization (odds ratio = 4.5), physical victimization with a weapon (odds ratio = 10.7), and sexual victimization (odds ratio = 10.2). Assessing for police victimization and other violence exposures may be a useful component of suicide risk screening in urban US settings. Further, community-based efforts should be made to reduce the prevalence of exposure to police victimization.

Keywords: Suicide, Violence, Aggression, Epidemiology, Sexual assault, Police abuse

Introduction

Violent encounters between the police and public have come under scrutiny following the proliferation of portable video recording technology and widespread dissemination of real-time footage through social media and news reporting organizations [1]. While the media have focused on immediate effects such as death or physical harm, these interactions may also result in significant psychological distress [2–4] and, potentially, suicidal ideation and attempts. The American Public Health Association recently issued a policy statement urging increased research and attention towards police victimization [5]. However, research on mental health correlates of police victimization has been minimal.

Evidence from genetic and twin studies suggests that suicidal behavior is driven by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, with environmental factors accounting for an estimated 57% of attributable risk [6]. Much of this environmental risk may be due to interpersonal trauma and victimization. In a recent meta-analysis, post-traumatic stress disorder and history of sexual trauma were the most robust predictors of suicidal behavior among individuals with ideation [7], although no studies in this meta-analysis included indicators of police violence. Several studies have shown that assaultive victimization (i.e., physical/sexual, as opposed to verbal/psychological) may be particularly relevant to subsequent risk for suicide attempts. In a nationally representative sample of US adults, assaultive violence was associated with greater odds for suicidal ideation and behavior (odds ratio = 6.2) and was particularly common among respondents who had made previous suicide attempts [8]. In a prospective cohort study of young adults in Baltimore, Maryland, PTSD due to assaultive victimization (but not non-assaultive) was associated with subsequent risk for suicide attempts [9]. Interpersonal and sexual violence were also identified as the correlates of suicide attempts with the largest effect sizes (compared to a range of other trauma exposures) among adults in the World Mental Health Surveys [10]. Given these findings, in conjunction with evidence that victimization by police in the USA is associated with trauma symptoms [3] and psychological distress [4], it is reasonable to hypothesize that police victimization (i.e., encounters with the police that are subjectively viewed by civilians to be assaultive, neglectful, or psychologically victimizing) would likewise be a notable correlate of suicidal ideation and behavior.

We conducted the Survey of Police-Public Encounters to examine the community-reported prevalence of police victimization and its mental health correlates. We hypothesized that police victimization, particularly more assaultive forms [8–10] such as physical and sexual victimization, would be associated with greater 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation and would be robust to adjustments for potential confounders including psychological disorder, past exposure to other forms of victimization, and involvement in criminal activities.

Methods

The Survey of Police-Public Encounters is a population-based survey of adults (N = 1615) residing in Baltimore (n = 226), New York City (n = 624), Philadelphia (n = 469), and Washington D.C. (n = 299). Details on sampling and survey procedures have been published elsewhere [4]. Briefly, participants were recruited through Qualtrics Panels, an online survey administration service that maintains a database of several million US residents who have consented to participate in survey research. Recruitment was conducted with the aim of falling within ±10% of 2010 US Census distributions for each included city, in terms of race/ethnicity, age, and gender. The sample was largely representative of the four included cities, although it diverged slightly from census distributions in some demographic categories (i.e., oversampled Whites and the 25–44 age group in the total sample, and females in Philadelphia only; further details in published previously [4]). Missing data were handled by creating a dummy-coded attribute indicating missing (yes/no) for each covariate with missing data. Participants were financially compensated based on standard Qualtrics Panels rates. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Measures

Respondents were assessed for self-reported demographics, lifetime history of victimization by the police, 12-month suicide attempts and ideation, lifetime psychological disorder, past exposure to intimate partner violence and other forms of sexual violence, and lifetime involvement in criminal activity. Demographic variables included gender (male/female/trans or other), age (18–24/25–44/45–64/>65 years), sexual orientation (heterosexual/non-heterosexual), race/ethnicity (White/Black/Latino/other), and income (in $20,000 increments up to $100,000+). Police victimization was assessed using the Police Practices Inventory [4], which includes five binary items assessing lifetime exposure to each domain of violence defined by the World Health Organization [2, 11]: physical (without a weapon: has a police officer ever hit, punched, kicked, dragged, beat, or otherwise used physical force against you?; with a weapon: has a police officer ever used a gun, baton, taser, or other weapon against you?), sexual (has a police officer ever forced inappropriate sexual contact on you, including while conducting a body search in a public place?), psychological (has a police officer ever engaged in non-physical aggression towards you, including threatening, intimidating, stopping you without probable cause, or using slurs?), and neglect (have you ever called or summoned the police for assistance and the police either did not respond, responded too late, or responded inappropriately?). Suicidal ideation and behavior were assessed with two items: “in the past 12 months, have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?”, and “in the past 12 months, have you ever attempted suicide?” A lifetime history of mental illness was assessed using a single self-report item: “have you ever been diagnosed with a mental illness? (for example: depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, etc.).” Exposure to sexual violence was assessed using a single item: “Has anyone else, other than a romantic or sexual partner (family member, acquaintance, or stranger) ever forced or pressured you to engage in unwanted sexual activity that you did not want to do? Unwanted sexual activity includes vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse or inserting an object or fingers into your anus or vagina.” Exposure to interpersonal violence was coded as a binary variable, indicating a positive response to any of three binary items assessing a lifetime history of threats, physical violence, or sexual violence from a romantic partner or significant other. Crime involvement was coded as a binary variable, indicating a positive response to any of four binary items assessing buying/selling drugs, use of injectable drugs, participation in robbery/burglary/larceny, and perpetration of assault or other forms of violence.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0 for Macintosh. Mantel-Haenszel chi-square analyses were used to test for unadjusted linear associations between the number of police victimization exposure subtypes reported and the prevalence of each suicide-related outcome. Separate blocked multivariable logistic regression models tested for associations between each domain of police victimization (physical, physical with a weapon, sexual, psychological, and neglect) and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, first unadjusted and then with adjustment for demographic variables, lifetime diagnosis of any mental illness, victimization history (interpersonal violence and sexual violence), and crime involvement.

Results

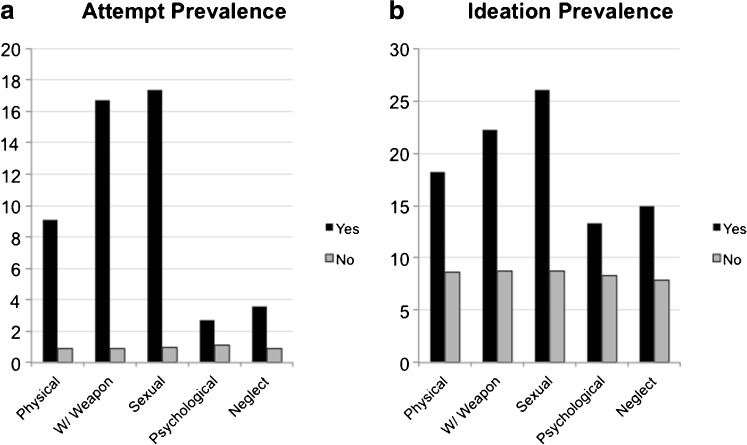

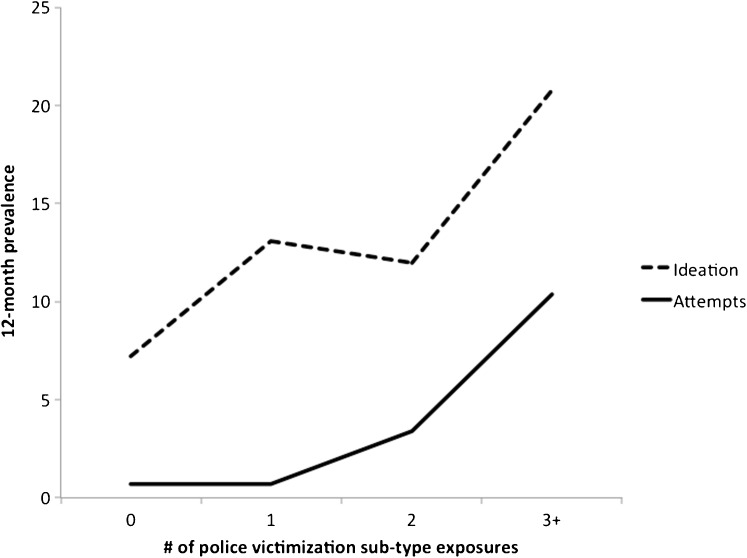

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. Lifetime exposures to police victimization and suicide-related outcomes were reported by a notable minority of the sample (Table 2). Police victimization was broadly more common among racial/ethnic minorities, sexual minorities, males, and people with lower income in these data, as previously reported [4]. Suicidal ideation and, to a substantially greater extent, suicide attempts were significantly more common among respondents endorsing each form of police victimization exposure (Fig. 1). Both suicide outcomes were more common among individuals reporting more subtypes of police victimization exposure in a linear dose-response fashion, specifically Mantel-Haenszel X 2 (df = 1) = 20.82, p < 0.001, for suicidal ideation and Mantel-Haenszel X 2 (df = 1) = 37.29, p < 0.001, for suicide attempts (Fig. 2). Logistic regression analyses adjusting for demographic factors, psychological distress, and criminal involvement confirmed that police victimization exposures, particularly physical victimization (OR = 4.5), physical victimization with a weapon (OR = 10.7), and sexual victimization (OR = 10.2), were associated with suicide attempts (Table 3), but not suicidal ideation (Table 4). Interactions between police victimization and race/ethnicity were not statistically significant and therefore not presented (data available on request).

Table 1.

Descriptive data for all demographic and potential confounder variables

| Variable | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 672 | 41.6 |

| Female | 932 | 57.7 |

| Trans | 11 | 0.7 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 276 | 17.1 |

| 25–44 | 763 | 47.2 |

| 45–64 | 467 | 28.9 |

| >65 | 109 | 6.7 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 873 | 54.1 |

| Black | 465 | 28.8 |

| Latino | 184 | 11.4 |

| Other | 93 | 5.8 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 1431 | 88.9 |

| Non-heterosexual | 178 | 11.1 |

| Missing | 6 | 0.4 |

| Income | ||

| <$20,000 | 163 | 10.1 |

| $20,000–39,999 | 272 | 16.8 |

| $40,000–59,999 | 301 | 18.7 |

| $60,000–79,999 | 298 | 18.6 |

| $80,000–99,999 | 195 | 12.1 |

| >$100,000 | 377 | 23.5 |

| Missing | 9 | 0.6 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 371 | 23.0 |

| Unsure | 25 | 1.5 |

| No | 1217 | 75.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 |

| Intimate partner violence | ||

| Yes | 350 | 21.7 |

| No | 1259 | 78.0 |

| Missing | 6 | 0.4 |

| Sexual violence | ||

| Yes | 169 | 10.5 |

| No | 1445 | 89.5 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 |

| Crime involvement | ||

| Yes | 304 | 18.8 |

| No | 1300 | 80.5 |

| Missing | 11 | 0.7 |

Table 2.

Descriptive and cross-tabulation data for primary exposure and outcome measures

| Variable | Suicidal ideation | Suicide attempts | Total sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Police victimization exposures | ||||||

| Physical | 18 | 18.6 | 9 | 9.3 | 97 | 6.0 |

| Physical with a weapon | 12 | 22.6 | 9 | 17.0 | 53 | 3.3 |

| Sexual | 12 | 26.1 | 8 | 17.4 | 46 | 2.8 |

| Psychological | 40 | 13.5 | 8 | 2.7 | 297 | 18.4 |

| Neglect | 45 | 15.2 | 11 | 3.7 | 296 | 18.3 |

| Total sample | 149 | 9.2 | 23 | 1.4 | – | – |

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of suicide attempts (a) and suicidal ideation (b) by categories of police victimization exposure in the entire sample. All unadjusted chi-square comparisons between police victimization exposures and both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were significant (p < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts by the number of subtypes of endorsed police victimization

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios for associations between police victimization and suicide attempts

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Physical | 10.7 | 4.5–25.5 | 4.5 | 1.2–16.3 |

| Physical with weapon | 22.1 | 9.1–53.7 | 10.7 | 2.6–44.0 |

| Sexual | 21.8 | 8.7–54.5 | 10.2 | 2.6–39.9 |

| Psychological | 2.4 | 1.0–5.7 | 0.7 | 0.2–2.2 |

| Neglect | 4.1 | 1.8–9.3 | 1.4 | 0.5–3.8 |

aAdjusted for gender, age, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, income, lifetime psychiatric diagnosis, intimate partner violence exposure, sexual violence exposure, and crime involvement

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios for associations between police victimization and suicidal ideation

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Physical | 2.4 | 1.4–4.1 | 0.6 | 0.4–1.7 |

| Physical with weapon | 3.0 | 1.5–5.8 | 1.1 | 0.4–2.6 |

| Sexual | 3.7 | 1.9–7.3 | 1.9 | 0.8–4.6 |

| Psychological | 1.7 | 1.2–2.5 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.4 |

| Neglect | 2.0 | 1.4–2.9 | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 |

aAdjusted for gender, age, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, income, lifetime psychiatric diagnosis, intimate partner violence exposure, sexual violence exposure, and crime involvement

Discussion

Recent media coverage has highlighted the immediate effects of police victimization, but consideration and empirical evidence of potential collateral effects on mental health have been limited. This is the first study to our knowledge to examine the relation between police victimization and suicidal ideation and attempts, finding a drastically elevated 12-month prevalence of attempts among adults exposed to sexual or physical police victimization. Evidence that police victimization is associated specifically with suicide attempts (and not ideation) makes these findings clinically important. Difficulty identifying correlates and predictors of suicide attempts (as opposed to suicidal ideation) has been a central limitation in efforts to translate epidemiological data into policies and interventions that curb the steady and rising suicide rate in the USA [7]. This difficulty reflects both the higher prevalence of ideation relative to attempts and the long-standing practice to combine suicidal thoughts and behaviors into a single dichotomous variable, obscuring risk factors that may be specific to suicidal behavior [7, 15]. The magnitude of association did not vary by race/ethnicity, though police victimization may be a particularly salient risk factor among Black Americans, given their higher rates of exposure in these data [4] and in prior studies [12]. It is possible that tests of interaction by race/ethnicity were underpowered in our data, although the lack of interaction is consistent with the broader literature on victimization. Specifically, past research has shown that victimization is more commonly reported by Black and Latino Americans compared to Whites but is not necessarily more strongly associated with mental health issues among these groups [13].

Mechanisms

Victimization, and particularly assaultive victimization, has been linked to elevated risk for suicide attempts in several prior studies [8–10], although this is the first study to specifically examine the relations between police victimization and suicide attempts. Instances of interpersonal violence typically involve a differential in power [14] that may be particularly pronounced in police-civilian encounters, given the governmental and social authority bestowed upon police officers. While many prominent theories of suicide do not outline a specific role for victimization, it is likely that such exposure to violence can contribute towards one’s acquired capacity for suicide attempt, a key component of the transition from suicidal ideation to suicide attempt in both the interpersonal theory of suicide [15] and the three-step theory [16]. This is consistent with the larger associations between physical and sexual victimization and suicide attempts, but not ideation, in our data. A potential interpretation is that factors that are associated with suicidal ideation are common among people that may potentially be at greater risk to being exposed to police violence (i.e., various forms of social and economic adversity), and the experience of victimization can potentially contribute to that transition from thought to action, although this is currently speculative based on our cross-sectional data and in need of replication in a prospective design. While prior research has not specifically examined police abuse in relation to suicide, it was recently shown in the National Violent Death Reporting System data that legal and criminal problems were significant predictors of subsequent suicide in the USA [17].

Given our use of cross-sectional data, it is likewise feasible that people who make suicide attempts are more likely to interact with police and, therefore, more likely to be subject to police victimization. This explanation would be consistent with the specificity of associations for suicide attempts, which are likely to elicit emergency police contact, compared to suicidal ideation, which is less likely to elicit emergency contact. However, if attempts directly contribute to victimization risk, it is not clear why the associations would then be specific to assaultive forms of police victimization, as shown in these data, weakening support for this explanation.

Limitations

Online data collection allows for the efficient collection of large quantities of survey data but may be susceptible to sampling biases, given that not all adults have equal likelihood of participating in online surveys (i.e., non-probability sampling), although significant efforts were made to ensure that the sample was generally representative of the included cities (for more details on survey methodology, see the primary paper of the Survey of Police-Public Encounters methods) [4]. Nonetheless, it is likely that the oversampling of White adults (relative to the true population distribution) may have led to underestimates of police victimization, given that prevalence rates are lowest among these groups. Our measures of police violence also did not provide sufficient contextual information to determine whether instances of violence were excessive or appropriate for the situation; this is of particular concern for physical violence, which may at times be warranted in police practice, but of less concern for sexual violence, which is less likely to be considered justified. Additional potential limitations include the lack of specific data on PTSD diagnosis, which may mediate the association between victimization and suicide attempts [9], and an insufficient sample size (given the low prevalence of attempts) to test for interaction by gender, which may moderate associations between victimization and suicide attempts [18]. We also did not have data on arrest history, incarceration history, or childhood victimization exposure, which potentially confound the associations in this study. The use of computerized self-report measures such as those used in this survey has been shown to improve reporting of undesirable or stigmatized behaviors [19], such as victimization and suicidal behavior, but also could not be independently corroborated in our survey design. Further, the primary suicide-related outcome variables were assessed using a single item each, which is typical for large epidemiological survey studies [20] but may be less reliable than multi-item assessments. The overall prevalence of suicidal ideation and behavior in this study was low but typical of prior general population studies [20], which can affect the reliability of regression analyses. Given our conservative statistical adjustments for potential confounds and the large odds ratios in the main analyses, it is unlikely that the small cell sizes have lead to fall positive findings; however, the magnitude of the estimated effect sizes may be less reliable and should be replicated as larger data sets assessing police victimization become available. It would also be worthwhile to replicate these findings in clinical samples, where the prevalence of suicidal behavior (and likely also victimization exposure) would expectedly be notably higher. Finally, the use of cross-sectional data limits our ability to make causal inferences.

Implications and Conclusions

Our data suggest that assaultive forms of police victimization are strongly associated with suicide attempts, which is particularly notable, given that correlates of suicide attempts, as opposed to suicidal ideation, are comparatively rare in the epidemiological literature [21]. A compelling possibility is that police victimization can potentially contribute to risk for suicide attempts. This is evidenced in our data by the stronger associations with more severe and assaultive forms of victimization (i.e., sexual and physical) and would suggest that police victimization has powerful collateral effects, beyond the direct impact (i.e., physical injury, incarceration), which may create significant psychological distress. Preventing such victimization through trauma-informed trainings for police officers, and otherwise addressing the widespread trauma in many urban communities, may improve community mental health and potentially even reduce suicide attempts. Assessing for police victimization, along with other forms of assaultive victimization [8–10], can be a valuable component of screening for suicide risk. This is especially true for sexual and physical victimization (particularly with a weapon), which should be further replicated in clinical help-seeking and criminal justice samples. Further, additional research effort should be made to determine whether the effects of police violence are fully independent of the effects of other types of violence exposure (e.g., interpersonal violence as tested here, but also childhood trauma exposure); it is feasible, given that police violence originates from the state rather than an individual and is defined by the substantial police-civilian power differential, although this is speculative at this time. Additionally, individuals who report exposure to police victimization in mental health services should be screened for suicide risk and provided with trauma-informed psychosocial support. Further prospective research is needed to better understand whether the associations between police victimization and suicide attempts are causal; if so, approaches to reduce exposure to police victimization may positively impact rates of suicide attempt. Steps that may improve police-public interactions include greater accountability for police officers [22, 23] and training to counter implicit and, potentially, explicit biases that may influence the excessive use of force [24, 25], and trauma informed training for police officers so that they may understand the impact of police victimization on the mental health of the citizens. Community-based approaches can focus on building positive relations between the police and general public in disadvantaged urban communities and can provide outreach to victims of police violence in neighborhoods where such interactions are more prevalent.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an intramural research grant from the University of Maryland, Baltimore (principal investigator: Jordan DeVylder). The funder had no role in the conduct of the study or dissemination of the results. Jordan DeVylder, University of Maryland School of Social Work, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Brucato B. The new transparency: police violence in the context of ubiquitous surveillance. Media Commun. 2015;3:39–55. doi: 10.17645/mac.v3i3.292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. Characterizing perceived police violence: implications for public health. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1109–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, Link BG. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:2321–2327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVylder J, Oh H, Nam B, Sharpe T, Lehmann M, Link B. Prevalence, demographic variation and psychological correlates of exposure to police victimisation in four U.S. cities. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Public Health Association. Law enforcement violence as a public health issue. http://apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2016/12/09/law-enforcement-violence-as-a-public-health-issue. Accessed 21 Dec 2016.

- 6.McGuffin P, Marušič A, Farmer A. What can psychiatric genetics offer suicidology? Crisis. 2001;22:61–65. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.22.2.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May AM, Klonsky ED. What distinguishes suicide attempters from suicide ideators? A meta-analysis of potential factors. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon TR, Anderson M, Thompson MP, Crosby A, Sacks JJ. Assault victimization and suicidal ideation or behavior within a national sample of US adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:42–50. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.42.22181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts in a community sample of urban American young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:305–311. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Hwang I, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations between traumatic events and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS. 2010;5:e10574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross CT. A multi-level Bayesian analysis of racial bias in police shoottings at the county-level in the United States, 2011-2014. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormond R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobash RE, Dobash RP. Women, Violence and Social Change. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2003.

- 15.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klonsky ED, May AM. The three-step theory (3ST): a new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int J Cogn Therapy. 2015;8:114–129. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hempstead KA, Phillips JA. Rising suicide among adults aged 40-64 years: the role of job and financial circumstances. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiet QQ, Finney JW, Moos RH. Recent sexual abuse, physical abuse, and suicide attempts among male veterans seeking psychiatric treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:107–113. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeVylder JE, Lukens EP, Link BG, Lieberman JA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adults with psychotic experiences: data from the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology surveys. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:219–225. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nock MK, Kessler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:616–623. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prenzler T, Porter L, Alpert GP. Reducing police use of force: case studies and prospects. Aggress Violent Behav. 2013;18:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Angelis J, Wolf B. Perceived accountability and public attitudes toward local police. Criminal Justice Stud. 2016;12:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Correll J, Park B, Judd CM, Wittenbrink B, Sadler MS, Keesee T. Across the thin blue line: police officers and racial bias in the decision to shoot. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92:1006–1023. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelman A, Fagan J, Kiss A. An analysis of the New York City police department’s “stop-and-frisk” policy in the context of claims of racial bias. J Am Stat Assoc. 2012;102:813–823. doi: 10.1198/016214506000001040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]