Abstract

Neighborhood-level structural interventions are needed to address HIV/AIDS in highly affected areas. To develop these interventions, we need a better understanding of contextual factors that drive the pandemic. We used multinomial logistic regression models to examine the relationship between census tract of current residence and mode of HIV transmission among HIV-positive cases. Compared to the predominantly white high HIV prevalence tract, both the predominantly black high and low HIV prevalence tracts had greater odds of transmission via injection drug use and heterosexual contact than male-to-male sexual contact. After adjusting for current age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and most recently recorded CD4 count, there was no statistically significant difference in mode of HIV transmission by census tract. However, heterosexual transmission and injection drug use remain key concerns for underserved populations. Blacks were seven times more likely than whites to have heterosexual versus male-to-male sexual contact. Those who had Medicaid or were uninsured (versus private insurance) were 23 and 14 times more likely, respectively, to have injection drug use than male-to-male sexual contact and 10 times more likely to have heterosexual contact than male-to-male sexual contact. These findings can inform larger studies for the development of neighborhood-level structural interventions.

Keywords: Disparities, Geography, HIV, Injection drug use, Race, Sexual behaviors

Introduction

Why is it that place matters? This paper seeks to provide a beginning understanding of why where people live, work, and interact has a great influence on their health generally, and more specifically on disparate HIV/AIDS rates. Since the beginning of the epidemic in the USA, death tolls among people living with AIDS have been greatest among men who have sex with men (MSM; N = 306,885), injection drug users (N = 184,673), and heterosexuals (N = 89,683) [1]. While individual behaviors (e.g., non-condom use) lead to some reported modes of HIV transmission, the relationship between behavior and environmental characteristics cannot be negated [2, 3]. Growing evidence substantiates geographic influences on both HIV risk-related behaviors and outcomes. For example, in 2013, the rate of HIV diagnosis was three times higher among people living in metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more than in non-metropolitan areas (23.6 versus 7.7, respectively) [4]. Heightened HIV prevalence rates in impoverished urban neighborhoods in the USA exceed standard definitions of a generalized epidemic [5]. Moreover, spatial and sociodemographic differences wash out traditional racial/ethnic effects seen in overall HIV prevalence rates [5]. An understanding of how/whether modes of transmission differ by race/ethnicity and geographical area can be used to begin to disentangle these relationships and inform targeted HIV initiatives.

It is not simply the negative structural conditions of a neighborhood that shape the HIV epidemic. Instead, we argue that it is the effect of those conditions on the individuals who are exposed to them, alongside the fact that health inequities and poorer health outcomes have historically trended with such characteristic neighborhood disadvantage [6–10]. Latkin et al. [11] outline potential pathways from neighborhood factors to HIV outcomes that are relevant for examination of differences in mode of HIV transmission: “Abandoned buildings, per se, do not ‘cause’ HIV acquisition. However, abandoned buildings may be settings where HIV risk behaviors occur, they may be stressors or reduce collective efficacy, or they may be an indicator of neighborhood social economic status” (p. 215). Thus, place-based indicators are a proxy for deeper social and structural factors that contribute to HIV transmission. For example, neighborhoods which have high levels of vacant housing, burglary, drug sales, poverty, and low security presence also have higher reports of individuals who have sex in exchange for money and sex with drug users, both of which are documented HIV risk-related behaviors [12–15]. Further, neighborhoods with a higher percentage of abandoned houses, previously incarcerated populations, and lower percentages of married families have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections [16, 17].

Hence, the conditions where people live, work, and interact influence their decisions and behaviors, such as “survival sex” to meet basic needs [18] or higher drug ties as a means of coping with unemployment in neighborhoods with high proportions without a high school education [19]. Moreover, these factors trend with greater HIV prevalence, and researchers have demonstrated that individuals who live in high HIV prevalence areas are more likely to engage in spatial assortativity (selection of sexual partners from geographic areas similar to one’s own) than residents of lower prevalence areas, which increases the probability of selecting an HIV-positive partner [20]. In these ways, pathways from neighborhood characteristics to individual HIV transmission can be established. Both the psychological effects of exposure to such factors in certain neighborhoods [21] as well as disparities in access to relevant aid and resources can increase HIV transmission in some neighborhoods [22].

All neighborhoods, however, are not alike, and not all, even those with similar characteristics, are equally affected. For example, some neighborhoods in cities such as Philadelphia, PA, bear disproportionate disease burden, while others do not. Philadelphia’s estimated HIV incidence was two times the national rate as of 2013; about 600 to 700 new HIV cases are diagnosed each year [23]. Nearly two thirds of the city’s cumulative HIV/AIDS cases are among blacks, and in 2014, the number of HIV cases among blacks was almost twice that of whites and Hispanics combined [23]. Brawner et al. [24] identified overcrowding, disadvantage, permeability in neighborhood boundaries, and availability and accessibility of health-related resources as primary contributors to these disparities and heightened HIV/AIDS rates in the city. Additionally, Eberhart et al. discovered that spatial patterns independently predicted hotspots for poor linkage to care, retention in care, and viral suppression in Philadelphia’s HIV/AIDS cases [25].

There is a growing body of research that examines geographic, social, and sexual network influences on HIV/AIDS [26–28]. Additional research is needed to examine the influence of these HIV-related drivers on the interplay of HIV/AIDS and illegal substance use among highly affected subpopulations (e.g., black MSM, heterosexuals, those who engage in injection drug use [IDU]). For example, within the USA, HIV rates among MSM are startling. The HIV prevalence rate among black MSM, however, is twice that of white MSM despite the fact that black MSM engage in similar or lower HIV risk behaviors such as condom use, fewer sexual partners, and less substance use [29–33]. In the same way, black women have increased risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) than white women of similar socioeconomic background in spite of having fewer partners and more condom use [34, 35]. While IDU transmission has steadily declined, strategies are needed to engage and retain injection drug users in substance abuse treatment—particularly given documented high-risk behaviors in this group [36]. However, place-based disparities also exist in substance abuse treatment, with lower treatment rates in areas with the highest percentages of black, Latino, and low-income residents [37].

In addition to risks associated with IDU, studies have found that non-injection drug users, such as those who use crack cocaine, are homeless, or have mental health disorders, are at increased risk for HIV, and engage in more risk behaviors, such as sex in exchange for illegal substances [15, 38–40]. But as several researchers have suggested [41–43], where these subpopulations live is an essential driver that not only creates but also maintains the disparity [11, 44]. Within these neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage, social and sexual networks also influence the interplay of drug use, sex, and disparate HIV incidence and prevalence rates [8, 15, 34, 45–47]. Hence, to have any hope of effectively addressing HIV/AIDS disparities among MSM, heterosexual, and IDU populations, researchers need to examine the intersectional influence of place-based factors, resource availability, and social networks on disproportionate HIV incidence and prevalence rates.

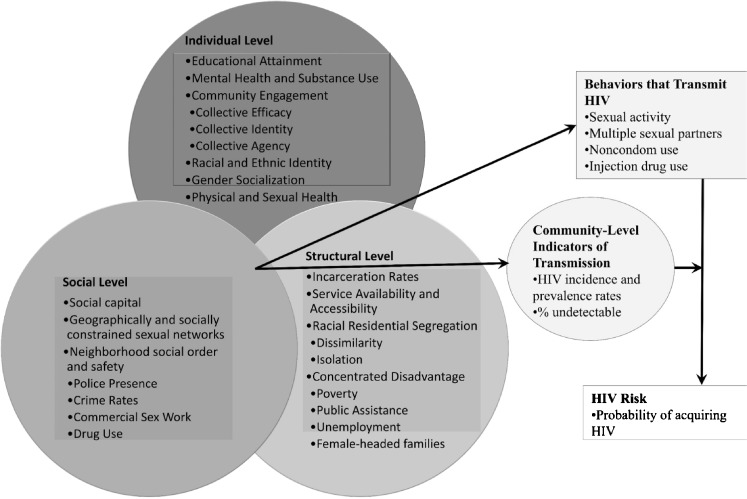

Underlying geographical factors (e.g., place-based characteristics) that contribute to disparities in HIV transmission and disease burden are poorly understood. To fill this gap, we conducted a study to explore racial/ethnic and geographic differences in mode of HIV transmission—IDU, male-to-male (MTM) sexual contact, heterosexual contact—in specific neighborhoods of Philadelphia, an urban HIV epicenter characterized by differences in HIV infection and race/ethnicity. The investigation was guided by a comprehensive model for understanding HIV disease burden in black communities (see Fig. 1) [48]. The model posits four pathways that are useful to examine HIV transmission: (1) multilevel factors (e.g., mental health, social capital, poverty) interact to influence community-level indicators of HIV transmission (e.g., HIV incidence rates); (2) these multilevel interactions also influence behaviors that transmit HIV (e.g., injection drug use); (3) the association between behaviors that transmit HIV and subsequent HIV risk is mediated by community-level indicators of HIV transmission in different geographic locations (e.g., community viral load); and (4) HIV risk/“geobehavioral vulnerability to HIV”—“the probability of HIV acquisition based on what you do, where you do it, and who you do it with”—is the product of multilevel interactions that create and sustain the risk context in certain populations and geosocial spaces (p. 101). Altogether, the model lends itself to empirical testing to better understand HIV/AIDS outcomes. Guided by this framework, the data generated from this study are critical to support the development of neighborhood-level structural interventions to address the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Guiding conceptual model. Adapted from Brawner [48]

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. The multiphase project ran from October 2011 through July 2013. While a city-wide analysis would have been ideal, resources available for the larger study restricted the time-intensive study activities to four census tracts. For the larger investigation, published elsewhere [24], we conducted a multimethod, comparative neighborhood-based case study in four Philadelphia census tracts on individual-level, social-level, and structural-level factors that contribute to the HIV/AIDS epidemic among black Philadelphians. The larger study included engagement of key stakeholders and an in-depth community ethnography, including field visits, observation, and conversations with residents and business owners, in the four study areas.

Given the small number of census tracts that could be accommodated by our pilot study, we sought to achieve maximal difference across the areas according to racial/ethnic composition and HIV disease burden—both neighborhood factors noted above to be linked with HIV transmission. Thus, we categorized and ranked Philadelphia’s 359 available census tracts by the predominant racial/ethnic composition (black or white) and HIV disease burden (incidence and prevalence). To account for other important factors in understanding the local epidemic, the four census tracts were chosen from the available pool based on the following criteria: (1) high (10 or more cases) or low (less than 5 cases) number of new HIV cases in the last year and high (35 or more cases) or low (less than 5 cases) AIDS prevalence, (2) predominantly (more than 85%) black or white area, (3) total population greater than 1000, and (4) percent male population comparable to Philadelphia’s male population. The categorization and selection criteria allowed us to conduct within and across census tract and population examinations. HIV/AIDS rates per tract were determined from census tract maps through the local health department [49]. The remaining criteria were determined through the 2009 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates [50].

Findings from the in-depth community ethnography are published elsewhere [24]. Briefly, the predominantly black low HIV incidence neighborhood had relatively low population and housing density, the fewest vacant lots, and the lowest number of indicators of social disorder (e.g., thefts, vandalism, disorderly conduct). Research team observations and resident reports in the area noted more green space (e.g., an arboretum is a central feature of the census tract) and increased perceptions of neighborhood safety, but limited healthcare resources; there were no HIV/AIDS-related agencies in the area. The predominantly black high HIV incidence tract had the greatest number of vacant lots and highest number of indicators of social disorder (e.g., criminal homicides, narcotics violations, prostitution). While the research team felt unsafe and was distinguished as “outsiders” by residents, community cohesion was high and residents reported trusting and helping each other. There were no HIV/AIDS-related agencies in the area, but there were several other programs and resources (e.g., literacy, gainful employment). The predominantly white low HIV incidence tract had high incidents of theft and vandalism despite resident reports of low crime rates. There were also a variety of resources in the area, including health clinics. A former HIV awareness program was noted by residents to have closed due to a loss in funding. Residents reported low community cohesion; however, it appeared that there were subpopulations who took care of each other (e.g., those residing in the estates around a park). Lastly, the predominantly white high HIV incidence area had the smallest total population but highest population and housing density of all of the tracts. From the research team observations and census tract-level sociodemographic indicators, the area was the most affluent among the tracts. There was also an abundance of health-related resources, including an HIV/AIDS agency.

This enhanced understanding of the social and structural characteristics of the four census tracts provides the backdrop for delving deeper into individual-level characteristics among HIV-positive cases in the areas. Here, we report findings from the secondary data analysis arm of the study where the aforementioned ethnographically identified cross-census tract differences provided context for the findings. We conducted a retrospective analysis of surveillance data of HIV-positive cases in the four study areas to explore racial/ethnic and geographic differences in the reported mode of HIV transmission. The mode of transmission was determined by the risk factors included in the medical record at the time of review (e.g., IDU), not by self-report questionnaire or patient interview. Data were extracted on people living with HIV/AIDS in the four census tracts from the enhanced HIV/AIDS reporting system (eHARS) through the Philadelphia AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO). Cases were included if they (1) resided in one of the four targeted census tracts, (2) were diagnosed on or before December 31, 2010, (3) were living as of January 1, 2006, and (4) were at least 18 years of age. There were a total of 339 eligible cases.

For the multivariate analyses, we excluded patients who had IDU in combination with a sexual risk factor to avoid confounding the data (e.g., adult men who have sex with men and inject drugs; n = 10), who had no risk factor reported or identified (n = 9), and one perinatal exposure. The distribution of the excluded cases did not substantially alter the sample size in the four study areas; nine cases were excluded from each of the predominantly white tracts, and two cases were excluded from the predominantly black low HIV prevalence tract. Race (X 2 = 6.01, p = 0.049) and insurance status (X 2 = 6.43, p = 0.04) were the only statistically significant differences between the included and excluded cases. More black cases (n = 14) were excluded than white (n = 3) or Hispanic cases (n = 3), and more cases with Medicaid (n = 6) were excluded than those with private insurance/health maintenance organization (HMO; n = 2) or no insurance (n = 3). The final sample was 319. The eHARS patient data were merged with sociodemographic data from the ACS for each census tract for the analyses.

Independent and Outcome Variables

Independent variables included current age, census tract of current residence (most recently recorded address), gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and most recently recorded CD4 count. Census tracts were categorized as (a) predominantly white high HIV prevalence, (b) predominantly black high HIV prevalence, (c) predominantly white low HIV prevalence, and (d) predominantly black low HIV prevalence. Gender was defined as current gender identification, not sex at birth. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic (all races). Insurance status was categorized as Medicaid, private/HMO, or uninsured. The outcome of interest was mode of HIV transmission categorized as MTM, heterosexual, or IDU. The aim was to determine racial/ethnic and geographic differences in mode of HIV transmission in the prescribed geographic areas.

Data Analysis

Summary statistics on the outcome and independent variables were computed in SAS v9.3 [51]. Group differences among the independent variables were assessed using chi-squared and generalized linear model (GLM). Two multinomial logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between census tract of current residence and mode of HIV transmission, adjusting for current age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and most recently recorded CD4 count. We adjusted for these factors given known associations between the variables and HIV outcomes [52–54]. In the first model, the reference group was IDU, and in the second, it was MTM. This approach—which was more conservative than analyzing differences between IDU and one aggregated sexual transmission category—allowed for comparisons between IDU and the sexual modes of transmission, as well as comparisons between MTM and heterosexual transmission. For each model, we used the estimated multinomial logistic regression coefficients’ Wald chi-squared and p value, along with the corresponding odds ratio and 95% Wald confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Census Tracts and Sample

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the selected census tracts (N = 4). Compared to the predominately white tracts, the predominantly black tracts had lower percentages of residents with GEDs (65.5 and 69.2% versus 96.9 and 83.5%), higher percentages of unemployed residents (19 and 33% versus 4 and 6%), and higher percentages of persons living below the federal poverty level (37 and 33% versus 9 and 19%). Table 2 highlights the sample characteristics of the extracted HIV/AIDS cases (N = 319). MTM was the predominant mode of HIV transmission (59.9%), with 14.7% of HIV cases attributable to IDU. Cases were predominately male (80.3%), with a mean age of 48.1 and most were black (47.3%). Statistically significant differences were noted in mode of transmission by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. Subtracting the average age at which cases were diagnosed with HIV from the average current age in the sample, persons were aware of their HIV status for approximately 12 years. The most recently recorded mean CD4 count was 117 (SD = 133) which is below the normal CD4 count (from 500 to 1000 cells/mm3); at the time of the study, this was also considered to be below the treating threshold of 350 cells/mm [55].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the included census tracts (N = 4)

| Characteristic | White × high prevalence (n = 185) | White × low prevalence (n = 16) | Black × high prevalence (n = 107) | Black × low prevalence (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study sample % | 58 | 5 | 33.5 | 3.4 |

| Predominate race %a | 85.9 White | 95 White | 95.4 Black | 86.9 Black |

| High school GED %a | 96.9 | 83.5 | 65.5 | 69.2 |

| Unemployment %a | 4.3 | 6.2 | 18.8 | 33.2 |

| % Below federal poverty levela | 8.6 | 10.3 | 36.5 | 32.5 |

| New HIV casesb | 10–14 cases | < 5 cases | ≥ 15 cases | < 5 cases |

| Existing AIDS casesb | ≥ 35 cases | < 5 cases | ≥ 35 cases | < 5 cases |

aData are from the 2009 American Community Survey 5-year estimates

bData are from the Philadelphia AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO) Surveillance Unit

Table 2.

Sample characteristics for HIV-positive participants by mode of transmission (N = 319)

| Characteristic | Total N = 319 | Male-to-male sexual contact n = 191 | Heterosexual contact n = 81 | Injection drug use n = 47 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) or mean (SD) | No. (%) or mean (SD) | No. (%) or mean (SD) | No. (%) or mean (SD) | F test or X 2 p | |

| Current age | 48.1 (10.9) | 49.2 (10.9) | 45 (11) | 50.3 (9.7) | F = 4.82, p = 0.009 |

| Current gender | X 2 = 120.01, p = <0.0001 | ||||

| Female | 63 (19.8) | 2 (1.1) | 47 (58) | 14 (29.8) | |

| Male | 256 (80.3) | 189 (98.9) | 34 (42) | 33 (70.2) | |

| Race/ethnicitya | X 2 = 80.03, p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Hispanic, all races | 27 (8.5) | 14 (7.6) | 8 (10) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Black, not Hispanic | 151 (47.3) | 54 (29.4) | 62 (77.5) | 35 (76.1) | |

| White, not Hispanic | 132 (41.4) | 116 (63) | 10 (12.5) | 6 (13) | |

| Health insuranceb | X 2 = 62.98, p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Medicaid | 65 (20.4) | 23 (13.1) | 28 (36.8) | 14 (31.8) | |

| Private insurance/HMO | 117 (36.7) | 101 (57.7) | 13 (17.1) | 3 (6.8) | |

| None | 113 (35.4) | 51 (29.1) | 35 (46.1) | 27 (61.4) | |

| Most recent CD4 count | 117.2 (133.3) | 119.8 (138.5) | 110.9 (121.4) | 117.4 (134.2) | F = 0.11, p = 0.8972 |

| Age diagnosed with HIV | 36.3 (9.76) | 35.5 (8.9) | 37.3 (12) | 37.6 (8.66) | F = 1.40, p = 0.2473 |

aRace/ethnicity data were missing for nine cases

bHealth insurance data were missing for 24 cases

Geographic Differences in Sociodemographic Characteristics and Mode of HIV Transmission

Table 3 describes geographic differences in sociodemographic characteristics by census tract of residence (N = 319). By the study’s design, census tracts were stratified by race and ethnicity; thus, significant racial and ethnic differences were expected to be noted (X 2 = 144.58, p < 0.0001). Gender (X 2 = 54.69, p < 0.001), insurance status (X 2 = 36.09, p < 0.001), mode of transmission (X 2 = 59.01, p < 0.001), and current age (F = 3.02, p < 0.05) also varied significantly by census tract. HIV-infected persons in the predominantly black low HIV prevalence tract were more likely to be females who were on Medicaid, or had no insurance, have heterosexual transmission, and were slightly younger (M age = 45.3). Persons in the predominantly white low HIV prevalence tract were almost exclusively males, were equally likely to have private insurance, Medicaid or no insurance, and more likely to have MTM transmission, with mean age of 46. Persons in the predominantly black high HIV prevalence tract were slightly more likely to be males, have no insurance, and have heterosexual transmission, with mean age of 46.2. Persons in the predominantly white high HIV prevalence tract were almost exclusively males and were most likely to have private insurance and MTM transmission, with mean age of 49.9. Cases of IDU mirror the poverty trends across the census tracts, where IDU reports were higher in both of the predominantly black census tracts (high and low HIV prevalence) than in both predominantly white tracts (high and low HIV prevalence; 24.3 and 27.3% versus 8.1 and 18.8%, respectively).

Table 3.

Bivariate associations between census tract, demographic variables, and mode of HIV transmission, Philadelphia, PA

| Characteristics | Census tract | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White × high prevalence (n = 185) | White × low prevalence (n = 16) | Black × high prevalence (n = 107) | Black × low prevalence (n = 11) | X 2 or F value | p value | |

| N (%) or mean (SE) | N (%) or mean (SE) | N (%) or mean (SE) | N (%) or mean (SE) | |||

| Race/ethnicitya | 144.58 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Hispanic, all races | 15 (8.4) | 4 (25.00) | 6 (5.7) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 42 (23.6) | 4 (25.00) | 96 (91.4) | 9 (81.8) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 121 (68) | 8 (50.00) | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Current gender | 54.69 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Female | 16 (8.7) | 2 (12.5) | 36 (33.6) | 9 (81.8) | ||

| Male | 169 (91.4) | 14 (87.5) | 71 (66.4) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Health insurance | 36.09 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Medicaid | 27 (15.8) | 6 (37.5) | 27 (27.8) | 5 (45.5) | ||

| Private insurance/HMO | 91 (53.2) | 5 (31.3) | 19 (19.6) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| No insurance | 53 (31) | 5 (31.3) | 51 (52.6) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| HIV mode of transmission | 59.01 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Injection drug use | 15 (8.1) | 3 (18.8) | 26 (24.3) | 3 (27.3) | ||

| Heterosexual contact | 28 (15.1) | 3 (18.6) | 44 (41.1) | 6 (54.6) | ||

| Male-to-male sexual contact | 142 (76.8) | 10 (62.5) | 37 (34.6) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Age diagnosed with HIV | 36.6 (9.47) | 31.6 (6.71) | 36.3 (10.79) | 36.6 (6.14) | 1.23 | 0.2986c |

| Current age | 49.9 (9.94) | 46 (7.27) | 46.2 (12.75) | 45.3 (8.56) | 3.02 | 0.0302c |

| Most recent CD4 count | 115.2 (142.09) | 132.3 (127.07) | 122.2 (124.12) | 76.8 (54.41) | 0.39 | 0.7583c |

aRace/ethnicity data were missing for nine cases

bHealth insurance data were missing for 24 cases

cGeneralized linear model (GLM) p values

Multinomial Analyses of Sociodemographic, Racial/Ethnic, and Geographic Disparities in Mode of HIV Transmission

In the unadjusted model with IDU as the reference category, significant differences were noted by census tract, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and age (see Table 4). Notably, compared to the predominantly white high HIV prevalence tract, the predominantly black high HIV prevalence tract (OR 0.10 [0.05–0.23]) and predominately black low HIV prevalence tract (OR 0.06 [0.01–0.39]) had lower odds of MTM versus IDU transmission. In the adjusted model, however, only differences by gender and insurance status remained. Females were five times more likely than males to have heterosexual versus IDU transmission (OR 5.39 [1.67–17.4]). Compared to those with private insurance/HMO, those with Medicaid and the uninsured were less likely to have MTM versus IDU transmission (OR 0.04 [0.01–0.24] and OR 0.07 [0.02–0.33], respectively).

Table 4.

Correlates of injection drug use (IDU) as mode of transmission versus male-to-male (MTM) sexual contact and heterosexual contact (N = 319; n = 47 IDU, n = 191 MTM, n = 81 heterosexual contact)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | MTM versus IDU Point estimate (95% CI) |

Heterosexual versus IDU Point estimate (95% CI) |

MTM versus IDU Point estimate (95% CI) |

Heterosexual versus IDU Point estimate (95% CI) |

| Census tractb | ||||

| White low prevalence | 0.29 (0.07–1.22) | 0.41 (0.07–2.34) | 0.21 (0.04–1.21) | 0.19 (0.02–2.31) |

| Black high prevalence | 0.10 (0.05–0.23)a | 0.61 (0.26–1.44) | 0.36 (0.09–1.33) | 0.25 (0.07–0.90) |

| Black low prevalence | 0.06 (0.01–0.39)a | 0.82 (0.17–3.85) | 1.7 (0.11–27.2) | 0.15 (0.02–1.17) |

| Genderc | ||||

| Female | 0.025 (0.01–0.12)a | 3.26 (1.52–7.00)a | 0.01 (< 0.001–0.15)a | 5.39 (1.67–17.4)a |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||

| Hispanic, all races | 0.16 (0.04–0.66)a | 0.75 (0.14–3.94) | 0.38 (0.05–3.19) | 0.2 (0.02–1.99) |

| Black, not Hispanic | 0.06 (0.02–0.16)a | 0.87 (0.27–2.75) | 0.16 (0.04–0.77) | 1.22 (0.22–6.76) |

| Health insurancee | ||||

| Medicaid | 0.05 (0.01–0.18)a | 0.46 (0.11–1.89) | 0.04 (0.01–0.24)a | 0.42 (0.08–2.23) |

| None | 0.06 (0.02–0.19)a | 0.30 (0.08–1.12) | 0.07 (0.02–0.33)a | 0.47 (0.09–2.35) |

| Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.96 (0.92–0.99)a | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) |

| Most recent CD4 count | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.0–1.01) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

aThe effects of Wald chi-squared significant difference p < 0.05

bWhite high prevalence serves as the referent group

cMale cases serve as the referent group

dWhite cases serve as the referent group

eCases with private insurance/HMO serve as the referent group

In the unadjusted model with MTM as the reference category (see Table 5), significant differences were also noted between MTM and heterosexual transmission by census tract, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, and age. Compared to the predominantly white high HIV prevalence tract, the predominantly black high HIV prevalence tract (OR 6.07 [3.23–11.41]) and predominately black low HIV prevalence tract (OR 14.00 [2.68–73.15]) had greater odds of heterosexual versus MTM transmission. Compared to whites, Hispanics were 5 times more likely (OR 4.76 [1.50–15.10]) and blacks were 15 times more likely (OR 15.23 [7.14–32.47]) to have heterosexual versus MTM transmission. After adjusting for the covariates, only gender, race/ethnicity, and insurance status remained significant. Blacks were seven times more likely than whites (OR 7.43 [2.03–27.29]) to have heterosexual versus MTM transmission. Compared to those with private insurance/HMO, those with Medicaid were 10 times more likely to have heterosexual versus MTM transmission (OR 9.69 [2.21–42.41]). The odds of IDU versus MTM transmission were 23 and 14 times higher among those with Medicaid (OR 22.85 [4.25–122.78]) and the uninsured (OR 14.40 [3.01–68.85]), respectively.

Table 5.

Correlates of male-to-male (MTM) sexual contact as mode of transmission versus injection drug use (IDU) and heterosexual contact (N = 319; n = 47 IDU, n = 191 MTM, n = 81 heterosexual)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | IDU versus MTM Point estimate (95% CI) |

Heterosexual versus MTM Point estimate (95% CI) |

IDU versus MTM Point estimate (95% CI) |

Heterosexual versus MTM Point estimate (95% CI) |

| Census tractb | ||||

| White low prevalence | 3.44 (0.82–14.36) | 1.40 (0.36–5.43) | 4.81 (0.83–27.82) | 0.91 (0.09–9.17) |

| Black high prevalence | 9.93 (4.42–22.30)a | 6.07 (3.23–11.41)a | 2.76 (0.75–10.11) | 0.68 (0.21–2.28) |

| Black low prevalence | 17.18 (2.59–113.98)a | 14.00 (2.68–73.15)a | 0.59 (0.04–9.41) | 0.09 (0.01–1.6) |

| Genderc | ||||

| Female | 40.09 (8.71–184.60)a | 130.63 (30.29–563.30)a | 123.65 (6.533–> 1.000)a | 666.39 (35.25–> 1.000)a |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||

| Hispanic, all races | 6.34 (1.52–26.44)a | 4.76 (1.50–15.10)a | 2.65 (0.31–22.40) | 0.54 (0.05–6.01) |

| Black, not Hispanic | 17.55 (6.44–47.84)a | 15.23 (7.14–32.47)a | 6.11 (1.30–28.69) | 7.43 (2.03–27.29)a |

| Health insurancee | ||||

| Medicaid | 20.49 (5.44–77.19)a | 9.46 (4.26–21.02)a | 22.85 (4.25–122.78)a | 9.69 (2.21–42.41)a |

| None | 17.82 (5.16–61.53)a | 5.33 (2.60–10.96)a | 14.40 (3.01–68.85)a | 6.71 (1.78–25.36) |

| Age | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.96 (0.94–0.99)a | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) |

| Most recent CD4 count | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

aThe effects of Wald chi-squared significant difference p < 0.05

bWhite high prevalence serves as the referent group

cMale cases serve as the referent group

dWhite cases serve as the referent group

eCases with private insurance/HMO serve as the referent group

Discussion

Place-based effects on health are well documented, with increasing attention given to the role of neighborhood context in HIV/AIDS disparities [11, 41, 56]. We sought to explore racial/ethnic and geographic differences in mode of HIV transmission in Philadelphia, an urban HIV epicenter. As a novel contribution to the literature, we had the added benefit of couching our secondary data analysis within the broader context of findings from an in-depth community ethnography. These cross-census tract, ethnographically identified differences helped explain the secondary data analysis findings and vice versa, thus leading us to argue that both methodologies are necessary to fully understand place-based associations in HIV transmission.

To characterize the two high HIV prevalence areas, persons in the predominantly black high HIV prevalence tract were more likely to be males and have no insurance, while persons in the predominantly white high HIV prevalence tract were almost exclusively males and were most likely to have private insurance. This describes two distinctly different demographics, and different approaches may be required to reach individuals in these communities. Like others [11, 14], we believe that neighborhood factors (e.g., percent of the population unemployed) shape HIV outcomes in multiple ways. These include an increase in individuals engaging in sex or drug trade for money, the stress of living in a characteristically disadvantaged neighborhood eroding traditionally protective factors such as social cohesion, and limited availability and/or accessibility of health-related resources to prevent and manage HIV infection. Combined, our findings further evidence the known intersection of injection drug use and concentrated disadvantage confronting black communities, especially those where HIV rates are high. We discovered that buried across census tracts are differences in social and structural indicators of HIV transmission (e.g., vacant lots, crime, limited availability of health-related resources), alongside racial/ethnic composition, mode of HIV transmission, and insurance status. Compared to the predominately white tracts, the predominantly black tracts had lower percentages of residents with GEDs, higher percentages of unemployed residents, and higher percentages of persons living below the federal poverty level. These factors are known correlates of poor HIV outcomes [8, 57–60] and point to the need for neighborhood-level structural interventions to improve health and reduce HIV transmission to get a handle on the local epidemic.

The proportion of heterosexual transmission in this study exceeds national statistics [61]. Both predominantly black tracts had the highest reports of heterosexual contact, while the predominantly white tracts had the highest reports of MTM. The unadjusted models confirmed these census tract-level differences; however, after adjusting for the covariates, the census tract-level differences washed out. Yet even in the adjusted model, blacks still had significantly higher odds of heterosexual versus MTM transmission; this was not an artifact of the gender composition of the predominately black tracts, as nearly two thirds of the sample in these tracts was male. These findings highlight the need to address heterosexual HIV transmission in predominantly black neighborhoods. This is particularly true for efforts with black heterosexual men, a demographic largely absent from our HIV/AIDS knowledge base [62]. Devastating rates of HIV incidence and prevalence among black MSM warrant immediate intervention. However, to preserve the health of black women and men, such intervention cannot be done at the expense of excluding black heterosexual populations from research and programmatic efforts. Instead of explicit focus on certain segments of black communities, we advocate for comprehensive approaches that address the social and structural drivers of neighborhood-level epidemics, attend to the nuances of black sexuality and sexual expression, and target behaviors (e.g., condomless vaginal or anal sex, injection drug use) that fuel HIV transmission versus targeting socially constructed identities.

Reports of IDU transmission were also higher than national averages [61]. The alarmingly high percentage of IDU among blacks and males and the higher odds of IDU among those on Medicaid and uninsured call for further inquiry. Similar to national trends, a higher percentage of whites had private insurance than blacks and Hispanics. Nelson et al. [63] discovered that social hardships including not having health insurance are associated with increased HIV risk. The researchers did not note geographic differences by city; however, the absence of a significant city-behavior interaction may have been due to the collection of individual data in broad regions versus an area-level examination (e.g., census tract). We discovered significant racial and geographic disparities in insurance status and mode of HIV transmission across census tract levels, a finer level analysis than the city or region. Given what we have learned with recent domestic outbreaks [64], interventions are needed (e.g., needle exchange programs) to prevent the continued spread of HIV among injection drug users. Efforts to refer this population for substance abuse treatment and ultimately engage and retain them in care are critical. Findings from the community ethnography in the four census tracts, however, indicate a limited availability of health-related resources. Some investigators, however, have successfully employed mobile medication units to address barriers associated with attending fixed-site clinics to provide substance abuse treatment for socially disenfranchised groups (e.g., blacks, uninsured) [65].

The most recently recorded mean CD4 count was relatively low across all tracts. An individual’s CD4 count is directly associated with his/her viral load and has implications for HIV transmission at both the individual and neighborhood levels [66–68]. In 2014, nearly one quarter of newly diagnosed HIV cases among Philadelphians were concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnoses, meaning that they were diagnosed with AIDS within 90 days of their HIV diagnosis [23]. These two statistics point to the need for earlier intervention in HIV screening and treatment. With Philadelphia’s rich resource context, agencies can consider strategic ways in partnering together at the neighborhood level (e.g., integrating and/or co-locating behavioral health and HIV services) to curb the epidemic. The findings from these analyses may provide some insight for intervention target and content.

The ethnographic findings from the larger study also highlight within racial/ethnic group differences at the neighborhood level that shed light on these findings. For example, the two predominantly black areas had distinctly different social and structural characteristics, with blacks in the census tract with more favorable social and structural characteristics (e.g., fewer residents below the federal poverty level) having better HIV outcomes [24]. Further, the increased likelihood of injection drug use in the predominantly black high incidence area in this arm of the study is consistent with the increased reports of vacant lots and narcotic violations in that area. Knowledge of such contextual nuances is key to the design of neighborhood-level intervention strategies [69, 70].

Several limitations should be considered. The analyses reported were cross-sectional and restricted to the four census tracts targeted for the larger pilot study. The available data only included data recorded in the medical record at one point in time, typically near diagnosis. Thus, the study design limits the ability to determine the temporal relationship between neighborhood characteristics and mode of HIV transmission. Longitudinal analyses can explore changes over time, as well as provide an overview of an individual’s health status (e.g., CD4 count) at multiple points of assessment. The small sampling from 359 available census tracts also limits generalizability to the broader Philadelphia area. A future city-wide analysis would be informative. Consequently, the selection of census tracts by high/low HIV prevalence and predominantly black/white demographic may have biased the main mode of HIV transmission discovered. For example, selecting a predominantly white high HIV prevalence census tract may have captured a more affluent group of MSM with access to HIV/AIDS agencies. With associations among race/ethnicity and mode of transmission, the inclusion of race/ethnicity may explain decreased effects in the adjusted models. That is, IDU transmission was significantly higher among blacks, who may be more likely to live in the city’s lower socioeconomic communities, which could wash out the association between mode of transmission and census tract [71]. Further, it is possible that separating MTM and heterosexual contact into two categories (versus one category of sexual activity) could have reduced power to detect differences; however, analyses of IDU versus aggregated sexual activity would have been less useful given distinctions between predominantly MSM and heterosexual communities.

The study used surveillance data that are captured through medical record review, which limits the information available for the analyses and contributes to missing data. Where people were diagnosed with HIV (e.g., prison system, emergency room) also determines the availability of a medical record, further limiting case representation and generalizability of these findings. The laboratory data were collected through routine surveillance and included address at the time of the lab report. As individuals move within the city (or to and from other cities), addresses in the surveillance dataset may not be as meaningful for census tract analyses as addresses obtained from direct patient interviews. Further, while we were limited to using census tract of current residence as a proxy for the geographic areas of the included cases, this strategy does not account for the fact that people may take part in HIV-risk related behaviors outside of their census tract of residence. Direct patient interviews with biomarker collection (e.g., CD4 count, viral load) can be used in future studies to collect more detailed information on meaningful geographic areas associated with study outcomes (e.g., sex/drug use locations), as well as past and current health and behaviors among HIV-positive individuals.

Lastly, we excluded 20 cases from the available dataset, 19 cases who had IDU in combination with sexual risk and 1 perinatal exposure. While this was justified, given the small number of cases in the black and white low HIV prevalence census tracts, the effect of the 19 IDU/sexual risk cases on the results could be significant in understanding the variables under study. However, with the way the excluded cases were distributed, they did not substantively increase the sample sizes in the two census tracts with fewer cases. Despite these limitations, the results provide relevant contextual information for future neighborhood-level structural approaches to HIV prevention.

Conclusions

These preliminary findings can be used to guide larger studies for the development of future neighborhood-level structural interventions. While it is well documented that risk profiles differ at the individual level, certain geographic locations also appear to have different mode of transmission profiles, with nuanced differences by gender, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. With mutual influences between individuals and the places in which they engage, it will also be important to consider the way in which neighborhood characteristics may be influenced by dominant risk behaviors (e.g., opening a needle exchange program in an area with high IDU prevalence). As we consider the role of place in health, it will be important to identify such mutable targets for inclusion in HIV risk reduction interventions and programming. This study was one step in that direction.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by pilot funding awarded to Dr. Brawner through the National Institute of Mental Health R25MH087217 (Guthrie, Schensul and Singer, PIs).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. (2012) 2014.

- 2.Frye V, Koblin B, Chin J, et al. Neighborhood-level correlates of consistent condom use among men who have sex with men: a multi-level analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):974–985. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9438-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowleg L, Neilands TB, Tabb LP, Burkholder GJ, Malebranche DJ, Tschann JM. Neighborhood context and black heterosexual men’s sexual HIV risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(11):2207–2218. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0803-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance in Urban and Nonurban Areas through 2013. 2013; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance_urban-nonurban.pdf. Accessed July 1, 2017.

- 5.Denning PH, DiNenno EA. Communities in crisis: is there a generalized HIV epidemic in impoverished urban areas of the United States? 2010; https://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/DenningandDiNenno_XXXX-1.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2017.

- 6.Cohen D, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. “Broken windows” and the risk of gonorrhea. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):230–236. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cubbin C, Brindis CD, Jain S, Santelli J, Braveman P. Neighborhood poverty, aspirations and expectations, and initiation of sex. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(4):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauermeister JA, Eaton L, Andrzejewski J, Loveluck J, VanHemert W, Pingel ES. Where you live matters: structural correlates of HIV risk behavior among young men who have sex with men in Metro Detroit. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(12):2358–2369. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nation M. Concentrated disadvantage in urban neighborhoods: psychopolitical validity as a framework for developing psychology-related solutions. J Commun Psychol. 2008;36(2):187–198. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massey DS. The age of extremes: concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography. 1996;33(4):395–412. doi: 10.2307/2061773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: a social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):210–224. doi: 10.1037/a0032704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schensul JJ, Levy JA, Disch WB. Individual, contextual, and social network factors affecting exposure to HIV/AIDS risk among older residents living in low-income senior housing complexes. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(suppl 2):S138–S152. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Généreux M, Bruneau J, Daniel M. Association between neighbourhood socioeconomic characteristics and high-risk injection behaviour amongst injection drug users living in inner and other city areas in Montréal, Canada. Int J Drug Pol. 2010;21(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latkin CA, Curry AD, Hua W, Davey MA. Direct and indirect associations of neighborhood disorder with drug use and high-risk sexual partners. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(Suppl 6):S234–S241. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudolph AE, Linton S, Dyer TP, Latkin C. Individual, network, and neighborhood correlates of exchange sex among female non-injection drug users in Baltimore, MD (2005-2007) AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):598–611. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen DA, Mason K, Bedimo A, Scribner R, Basolo V, Farley TA. Neighborhood physical conditions and health. J Inform. 2003;93(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Thomas JC, Sampson LA. High rates of incarceration as a social force associated with community rates of sexually transmitted infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Supplement 1):S55–S60. doi: 10.1086/425278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warf CW, Clark LF, Desai M, et al. Coming of age on the streets: survival sex among homeless young women in Hollywood. J Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford N, Borrell L, Galea S, Ford C, Latkin C, Fuller C. The influence of neighborhood characteristics on the relationship between discrimination and increased drug-using social ties among illicit drug users. J Community Health. 2013;38(2):328–337. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9618-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gindi RM, Sifakis F, Sherman SG, Towe VL, Flynn C, Zenilman JM. The geography of heterosexual partnerships in Baltimore city adults. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(4):260–266. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f7d7f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258–276. doi: 10.2307/3090214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latkin C, Weeks MR, Glasman L, Galletly C, Albarracin D. A dynamic social systems model for considering structural factors in HIV prevention and detection. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(Suppl 2):222–238. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9804-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philadelphia Department of Public Health. AIDS Activities Coordinating Office Surveillance Report, 2014. 2015; http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/2014%20Surveillance%20Report%20Final.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2016.

- 24.Brawner BM, Reason JL, Goodman BA, Schensul JJ, Guthrie B. Multilevel drivers of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among black Philadelphians: exploration using community ethnography and geographic information systems. Nurs Res. 2015;64(2):100–110. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberhart MG, Yehia BR, Hillier A, et al. Behind the cascade: analyzing spatial patterns along the HIV care continuum. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(Suppl 1):S42–S51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a90112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauermeister JA, Connochie D, Eaton L, Demers M, Stephenson R. Geospatial indicators of space and place: a review of multilevel studies of HIV prevention and care outcomes among young men who have sex with men in the United States. J Sex Res. 2017;54(4–5):446–464. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1271862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunn A, Yolken A, Cutler B, et al. Geography should not be destiny: focusing HIV/AIDS implementation research and programs on microepidemics in US neighborhoods. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):775–780. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clerkin EM, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: the effect of race on risky sexual behavior among black young men who have sex with men (YMSM) J Behav Med. 2011;34(4):237–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Johnson A, Emerson E. Exploring factors that underlie racial/ethnic disparities in HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):318–323. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9430-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Racial differences in same-race partnering and the effects of sexual partnership characteristics on HIV risk in MSM: a prospective sexual diary study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):329–333. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e5f8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. The effects of sexual partnership and relationship characteristics on three sexual risk variables in young men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):61–72. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman MB. A critical literature review to identify possible causes of higher rates of HIV infection among young black and Latino men who have sex with men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1206–1221. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr JC, Valois RF, Siddiqi A, Vanable P, Carey MP. Neighborhood condition and geographic locale in assessing HIV/STI risk among African American adolescents. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1005–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0868-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annang L, Walsemann KM, Maitra D, Kerr JC. Does education matter? Examining racial differences in the association between education and STI diagnosis among black and white young adult females in the US. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):110–121. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson C-A, Weng CX, French T, et al. Substance abuse treatment utilization, HIV risk behaviors, and recruitment among suburban injection drug users in Long Island, New York. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):305–315. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen H, Siegel C, Wanderling J, DiRocco D. Buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid dependence by income, ethnicity and race of neighborhoods in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;164:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Booth RE, Kwiatkowski CF, Chitwood DD. Sex related HIV risk behaviors: differential risks among injection drug users, crack smokers, and injection drug users who smoke crack. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58(3):219–226. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Wendel T, Marshall Iv DM, Hagan H. Correlates of selling sex among male injection drug users in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hughes E, Bassi S, Gilbody S, Bland M, Martin F. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35:80–94. doi: 10.2307/2626958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper HL, Des Jarlais DC, Tempalski B, Bossak BH, Ross Z, Friedman SR. Drug-related arrest rates and spatial access to syringe exchange programs in New York City health districts: combined effects on the risk of injection-related infections among injectors. Health Place. 2012;18(2):218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper HL, Linton S, Haley DF, et al. Changes in exposure to neighborhood characteristics are associated with sexual network characteristics in a cohort of adults relocating from public housing. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1016–1030. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0883-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neaigus A, Jenness SM, Reilly KH, et al. Community sexual bridging among heterosexuals at high-risk of HIV in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(4):722–736. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mustanski B, Birkett M, Kuhns LM, Latkin CA, Muth SQ. The role of geographic and network factors in racial disparities in HIV among young men who have sex with men: an egocentric network study. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):1037–1047. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0955-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilton L, Koblin B, Nandi V, et al. Correlates of seroadaptation strategies among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in 4 US cities. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(12):2333–2346. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1190-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuqua V, Scott H, Scheer S, Hecht J, Snowden JM, Raymond HF. Trends in the HIV epidemic among African American men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004-2011. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(12):2311–2316. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brawner BM. A multilevel understanding of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2014;43(5):633–643. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Philadelphia Department of Public Health AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO). HIV and AIDS in the City of Philadelphia: Annual Surveillance Report. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Department of Public Health;2009.

- 50.U.S. Census Bureau. 2005-2009 American Community Survey 2010; http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t. Accessed July 6, 2014.

- 51.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.3. Cary, NC2012.

- 52.Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, et al. Gender differences in sexual and injection risk behavior among active young injection drug users in San Francisco (the UFO study) J Urban Health. 2003;80(1):137–146. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Agwu AL, Metlay JP, Berry SA, Gebo KA. Health insurance coverage for persons in HIV care, 2006–2012. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2014;67(1):102–106. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edwards JK, Cole SR, Westreich D, et al. Age at entry into care, timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation, and 10-year mortality among HIV-seropositive adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(7):1189–1195. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):125–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blackstock OJ, Frew P, Bota D, et al. Perceptions of community HIV/STI risk among US women living in areas with high poverty and HIV prevalence rates. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):811–823. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Khan MR, Schwartz RJ, Miller WC. Sex ratio, poverty, and concurrent partnerships among men and women in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23(11):716–719. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prather C, Marshall K, Courtenay-Quirk C, et al. Addressing poverty and HIV using microenterprise: findings from qualitative research to reduce risk among unemployed or underemployed African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1266–1279. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McMahon J, Wanke C, Terrin N, Skinner S, Knox T. Poverty, hunger, education, and residential status impact survival in HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;15(7):1503–1511. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9759-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015. 2016;27 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2015-vol-27.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2016.

- 62.Bowleg L, del Río-González AM, Holt SL, et al. Intersectional epistemologies of ignorance: how behavioral and social science research shapes what we know, think we know, and don’t know about US black men’s sexualities. J Sex Res. 2017;54(4–5):577–603. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1295300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nelson LE, Wilton L, Moineddin R, et al. Economic, legal, and social hardships associated with HIV risk among black men who have sex with men in six US cities. J Urban Health. 2016;93(1):170–188. doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-0020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strathdee SA, Beyrer C. Threading the needle—how to stop the HIV outbreak in rural Indiana. New Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):397–399. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1507252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hall G, Neighbors CJ, Iheoma J, et al. Mobile opioid agonist treatment and public funding expands treatment for disenfranchised opioid-dependent individuals. J Subst Abus Treat. 2014;46(4):511–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kranzer K, Lawn SD, Johnson LF, Bekker L-G, Wood R. Community viral load and CD4 count distribution among people living with HIV in a South African township: implications for treatment as prevention. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2013;63(4):498–505. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318293ae48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Attia S, Egger M, Müller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(11):1397–1404. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b7dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Das M, Chu PL, Santos G-M, et al. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Herbst JH, Beeker C, Mathew A, et al. The effectiveness of individual-, group-, and community-level HIV behavioral risk-reduction interventions for adult men who have wex with men: A systematic review. Am J Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(Supplement 4):38–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rhodes SD, Kelley C, Simán F, et al. Using community-based participatory research (CBPR) to develop a community-level HIV prevention intervention for Latinas: a local response to a global challenge. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(3):e293–e301. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cooper HLF, West B, Linton S, et al. Contextual predictors of injection drug use among black adolescents and adults in US metropolitan areas, 1993–2007. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):517–526. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]