Abstract

Background

Amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) are commonly prescribed in Nigeria either as a monotherapy or in combination with other drugs. The present study was designed to investigate the antihypertensive efficacy of monotherapy with amlodipine or HCTZ and their effects on electrolyte profile in patients with mild to moderate hypertension.

Methods

A single-blind randomized clinical study was used; fifty patients newly diagnosed with mild to moderate hypertension (aged 33 to 60 years) were recruited and divided into two groups: amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide each comprising of 25 subjects. The subjects received 5mg of amlodipine or 25mg of hydrochlorothiazide in their respective group once daily for 4 weeks. Blood pressure, serum and urine electrolytes were measured at baseline and weekly throughout the experiment.

Results

At the end of follow up, amlodipine reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure significantly more (p<0.001) than HCTZ. At the end of follow up, blood pressure was reduced to normal in 80% of the subjects in amlodipine group compared to 50% in HCTZ. Amlodipine had no significant effect on electrolyte profile of subjects unlike HCTZ which significantly changed both their serum and urine electrolytes.

Conclusions

Monotherapy with amlodipine was more effective than HCTZ in black patients with mild to moderate hypertension and in addition maintained electrolyte balance.

Introduction

Hypertension is a globally common condition that contributes to preventable disease and death.1 Essential hypertension is the most common cardiovascular disease among black Africans2 and it is also a significant cause of adult morbidity and mortality.3 The recommended initial treatment for hypertension in non-black subjects may involve the administration of either angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), calcium channel blockers or thiazide-type diuretic, while the recommended treatment for black hypertensive subjects was with either the calcium channel blockers (such as amlodipine) or with the thiazide-type diuretics (such as HCTZ).1 An earlier guideline recommended the use of thiazide diuretics in the treatment of uncomplicated hypertension, either as a monotherapy or in combination with other classes of anti-hypertensive drugs.4 However, a trial that evaluated this guideline found that a combination therapy with amlodipine was more efficacious at reducing blood pressure in high-risk patients than a combination therapy with HCTZ.5,6 Amlodipine and HCTZ are commonly prescribed in Nigeria as monotherapy and in combination with other antihypertensive drugs.7 Amlodipine monotherapy was reported to have achieved similar reduction in blood pressure in elderly patients as a combination therapy with HCTZ.8 Similarly, a previous study among Nigerians with essential hypertension showed that amlodipine was a more effective than HCTZ in reducing blood pressure.7

Hydrochlorothiazide was reported to produce significant adverse effects on the potassium levels of the subjects while amlodipine was neutral.9 Hyponatremia and hypokalemia were observed during the initiation of hydrochlorothiazide therapy in type 2 diabetic hypertensive Nigerian subjects, while amlodipine caused no significant clinical biochemical abnormality in their electrolyte profiles.7 The effects of amlodipine and HCTZ on electrolyte profile of black patients with mild to moderate hypertension remain poorly understood. The present study investigated the efficacy and effects of monotherapy with amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide on the electrolyte profile of Nigerians with mild to moderate hypertension.

Methods

Study location

The study was carried out in Enugu, the capital city of Enugu state of Nigeria. Enugu state is located in the South-East geopolitical zone of Nigeria. Enugu city has a population of about a million people, mostly Nigerians of the Igbo tribe. The inhabitants of the city are mostly public servants, traders and artisans. The study lasted for a period of 5 months.

Sample size

This was estimated using the method of Kadam and Bhalerao,10 as follows:

n is the required sample size,

Zα = 1.96 for 5% level of significance,

Z1 — β = 0.84 at 80% statistical power,

σ = common standard deviation,

Δ = difference between mean values in a previous study.11

Fifty patients (28 males and 22 females) newly diagnosed with mild to moderate hypertension and aged between 33 and 60 years attending the Medical Out Patient clinic of EnuguState University Teaching Hospital, Enugu, were consecutively recruited into the study. However, one female subject withdrew from the study for non-medical reasons; only 49 subjects completed the study. The study was carried out in line with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration for human studies, as amended and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Enugu State University Teaching Hospital (EC: ESUTTH/EC/11002).

Inclusion criteria

Consenting subjects newly diagnosed with mild to moderate hypertension using WHO guidelines.12 Mild hypertension is BP of 140–159/90–99mmHg while moderate is BP of 160– 179/100–109mmHg.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic heart disease, hepatic disease and cancer were excluded from the study. Pregnant women, individuals with evidence of secondary hypertension, chronic smokers and alcoholics were also excluded.

Those that met the inclusion criteria were randomly divided into 2 groups (amlodipine and HCTZ). The group and treatment given were concealed from the physicians that took the measurements.

Group 1

Patients in this group were given 5mg amlodipine (Pfizer, New York, USA) once daily before breakfast for 4 weeks.

Group 2

Patients were given 25 mg HCTZ (Esidrex®, Novarvatis, Switzerland) once daily before breakfast for 4 weeks.

Patients were given weekly appointments and a week worth of medication during each visit. Treatment adherence was monitored every 2 days via phone calls and clinical evaluation carried out weekly on their appointment day.

Blood pressure, serum and urine electrolytes were measured at baseline and weekly during treatment for 4 weeks.

Blood pressure measurement

Sitting BP was measured using Accoson® mercury sphygmomanometer. Two consecutive readings were taken from each subject at 5 minutes intervals and the average of these was calculated and taken as the mean blood pressure value. Readings were taken between 8.00 am and 10.00 am on their appointment. Any constrictive clothing on the arm was removed before measurement.

Serum electrolyte measurement

Venous blood (5 mL) was drawn from medial cubital vein into a vacutainer and allowed to coagulate for 25 minutes. The clot formed was removed by centrifuging at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatant (serum) was removed for analysis. Serum electrolyte (Na+, K+, and Cl−) levels were determined by ion selective electrode using Audicom automated electrolyte analyzer (AC9000 series), China.

Urine electrolyte measurement

Urine samples were collected in clean containers and Na+, K+ and Cl− measured using ion selective electrode analyzer (Audicom automated electrolyte analyzer; AC9000 Series), China.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as mean ± standard error of mean. Data were classified by groups and weeks of treatment and analyzed using SPSS Version 20 by IBM Corp. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences between groups, and further analysis was carried out using Bonferroni post-test (GraphPad prism 5.0). P values< 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

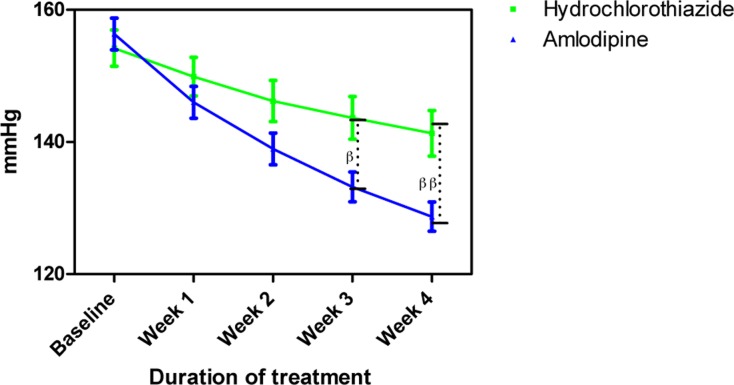

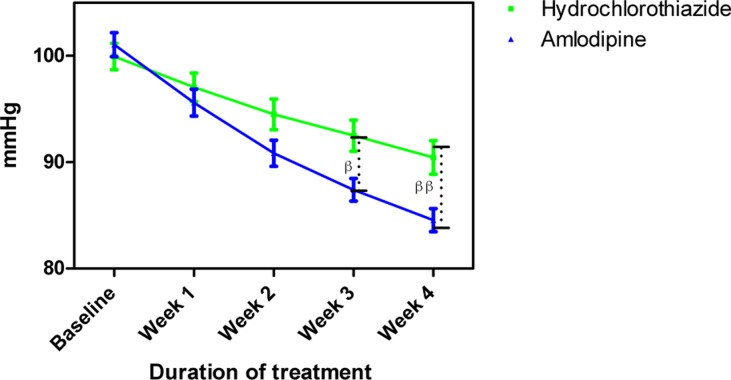

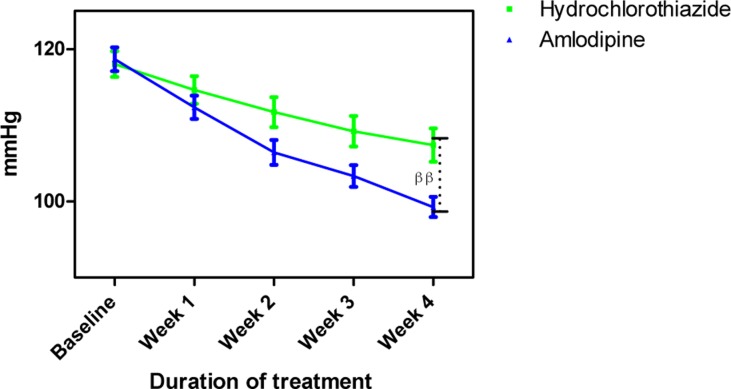

The mean age and BMI of amlodipine and HCTZ groups were not significantly different (Table 1). Amlodipine reduced SBP, DBP and MAP at the end of follow more than HCTZ group (Table 2). Amlodipine reduced SBP and DBP significantly more than HCTZ at weeks 3 and 4 and reduced MAP significantly more at week 4.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics and body mass index

| Characteristic | Amlodipine | Hydrochlorothiazide |

| Age (years) | 48.81±12..20 | 47.68 ± 10.32 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13 | 15 |

| Female | 12 | 10 |

| BMI (kg/m2) ± SD | 27.44 ± 4.20 | 26.88 ± 3.40 |

SD = standard deviation

Table 2.

Percentage change in blood pressure at the end of follow-up

| % change in blood pressure at week 4 |

Amlodipine | Hydrochlorothiazide |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) ± standard deviation |

−17.69 ± 3.12 | −8.55 ± 1.64 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) ± standard deviation |

−12.36 ± 2.40 | −5.22 ± 1.45 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) ± standard deviation |

−15.28 ± 2.31 | −8.12 ± 2.15 |

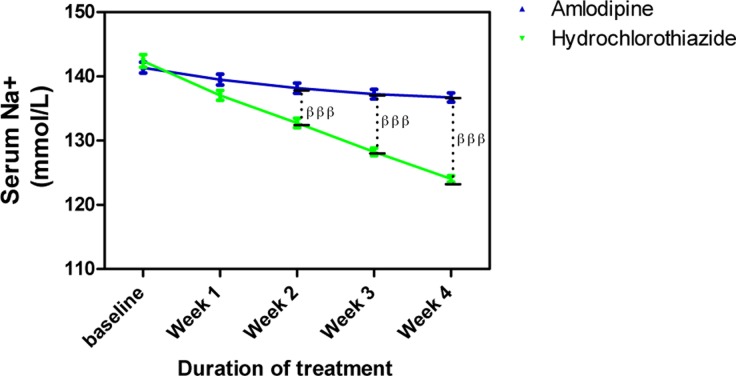

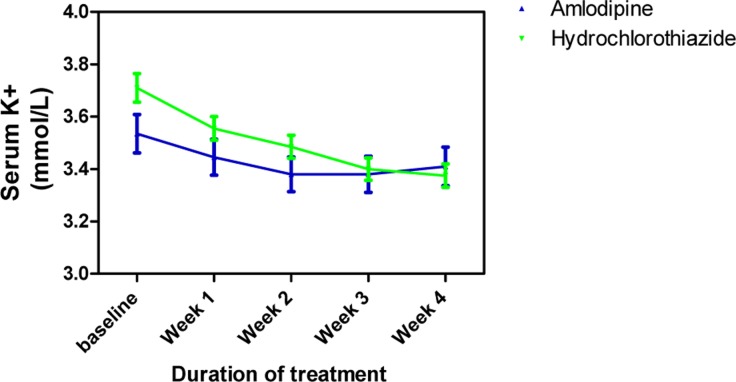

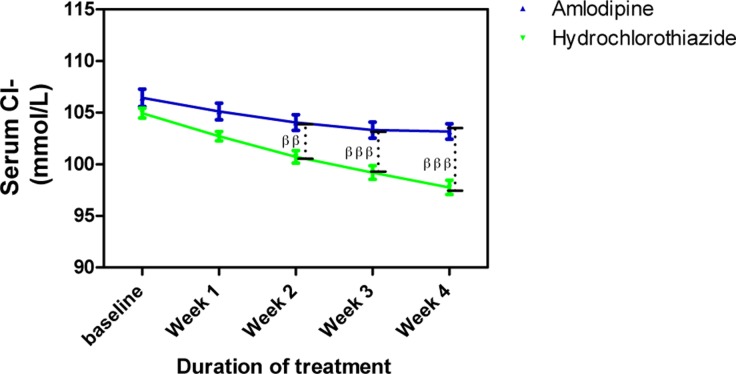

Amlodipine caused minimal changes in serum Na+ but HCTZ significantly reduced it; when both effects were compared to each other, the effect of HCTZ was significantly higher (p<0.001) at weeks 2, 3 and 4 (Figure 4). At the end of the follow up, amlodipine caused no change in serum K+ from baseline level whereas HCTZ reduced K+ from its baseline level. However, this difference was not significant throughout the duration of the study (Figure 5). Amlodipine had no significant effect on serum Cl− while HCTZ significantly reduced it. When compared to each other, HCTZ significantly reduced serum Cl− at weeks 2 (p<0.01), 3 (p<0.001) and 4 (p<0.001) (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Serum Na+ measurements following with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); βββP < 0.001 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad Prism 5.0)

Figure 5.

Serum K+ measurements following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); generated using Graphpad Prism 5.0.

Figure 6.

Serum Cl− measurements following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); generated using Graphpad Prism 5.0.

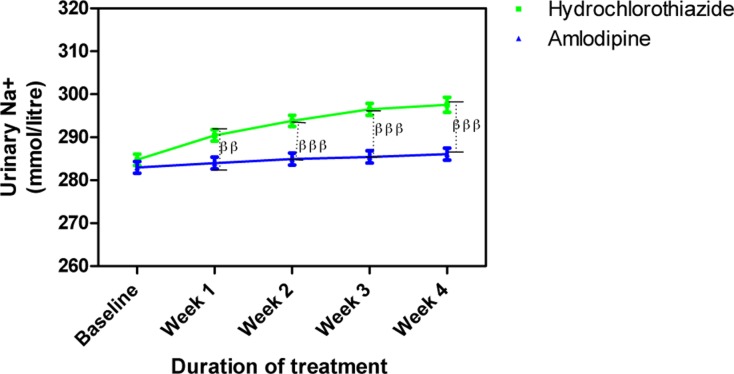

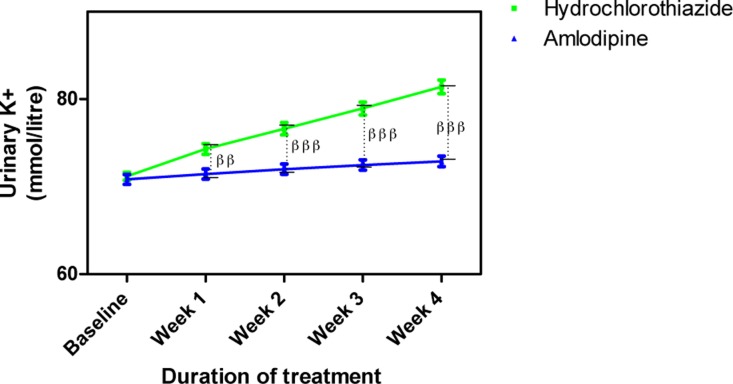

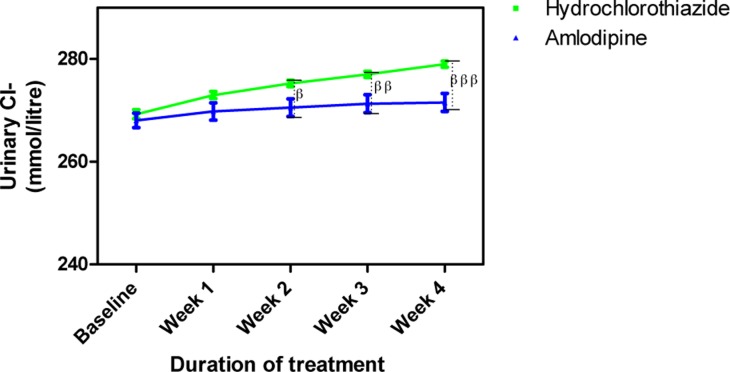

Amlodipine caused insignificant changes in urine electrolytes (Na+, K+ and Cl−) while HCTZ increased them. The changes in urine Na+ caused by HCTZ was significant at week 1 (p<0.01) and weeks 2–4 (p<0.001) when compared to amlodipine (Figure 7); changes in K+ also followed a similar pattern (Figure 8) while that of Cl− was significant at weeks 2 (p<0.05), 3 (p<0.01) and 4 (p<0.001) (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Urine Na+ concentration following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); ββP < 0.01, βββP < 0.001 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad Prism 5.0).

Figure 8.

Urine K+ concentration following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); ββP < 0.01, βββP < 0.001 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad Prism 5.0).

Figure 9.

Urine Cl− concentration following the administration of amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); βP < 0.05, ββP < 0.01, βββP < 0.001 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad prism 5.0).

No adverse side effect was observed in both groups, however, polyuria was observed.

Discussion

Both amlodipine and HCTZ significantly reduced BP in mild to moderate hypertensive subjects. At the end of follow up, blood pressure was reduced to normal in 80% of the subjects in amlodipine group compared to 50% in HCTZ. The efficacy of these drugs in the present study was higher than that earlier reported in a Nigerian population where monotherapy using 5 mg of amlodipine daily achieved 40% reduction to normal BP while 25mg of HCTZ daily produced 35% reduction to normal BP.13 The increased efficacy seen in the present study may be due to shorter duration of treatment and adequate monitoring of compliance via phone calls employed. Our study lasted for 4 weeks compared to 6 weeks in the above study and prolonged use of these drugs has been shown to produce lower antihypertensive effect13; monitoring of compliance was not indicated in the previous study whereas phone calls were used to monitor and ensure compliance in the present study. There was no significant difference between the antihypertensive efficacy of amlodipine and HCTZ in the previous Nigerian study whereas a significant difference between their efficacies was observed in this study. Apart from other factors mentioned above, the age of the subjects may be a contributing factor; the mean age of our subjects (48 years) was lower than that of the previous study (55 years) and HCTZ has been shown to become more effective with increasing age.14 The greater efficacy of amlodipine observed in the present study also agrees with earlier studies by Calvoet et al.,15 which reported that amlodipine was significantly more effective than hydrochlorothiazide in reducing sitting blood pressure in patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The efficacy of amlodipine in the present study also agrees with previous reports that monotherapy with nifedipine (a calcium channel blocker) was efficacious among Nigerians.16 The only side effect observed in both groups was polyuria, both drugs were tolerated among the subjects. Polyuria was due to diuretic action of HCTZ and renal vasodilatation caused by amlodipine.

Amlodipine caused no significant changes in serum electrolytes whereas HCTZ significantly reduced Na+, K+, and Cl− from their baseline levels. These results agree with that from an earlier study.13 Our results were also similar to those obtained from an earlier study where amlodipine was also reported to maintain electrolyte balance even among diabetic hypertensive patients.7 The results of the present study were also similar to those reported in earlier studies.17,18 Treatment with HCTZ significantly increased urine electrolytes of the subjects in the present study; this similar to earlier reports where HCTZ produced increase in urine electrolytes in patients with essential hypertension.7,18 The corresponding increase in urine electrolytes suggests that they were lost from blood.

In conclusion, short-term monotherapy with amlodipine was more effective than hydrochlorothiazide in mild to moderate hypertensive Nigerians; it did not cause electrolyte imbalance unlike HCTZ. These results suggest that amlodipine may be safer as a monotherapy in black essential hypertensive subjects.

Recommendation

There is need to review the current management strategy in Nigeria where diuretics especially thiazide diuretics are mainly prescribed as the first line drugs in treatment of hypertension. Amlodipine should be the first line drug since it is more effective and did not cause electrolyte imbalance; it is also affordable just like hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 1.

Systolic blood pressure measurements following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean; βP < 0.05, ββP < 0.01 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad Prism 5.0).

Figure 2.

Diastolic blood pressure measurements following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); βP < 0.05, ββP < 0.01 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad Prism

Figure 3.

Mean arterial blood pressure measurements following treatment with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide

Each point on the graph represents the average of at least 25 independent measurements. Error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM); ββP < 0.01 (hydrochlorothiazide versus amlodipine; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, using Graphpad Prism 5.0).

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this work.

References

- 1.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, et al. Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinkugbe OO. World epidemiology of hypertension in blacks. In: Hall WD, Saunders E, Shulman EB, editors. Hypertension in Blacks. Chicago, Ill: Yearbook; 1985. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Wilson PW, Anderson KM, Castelli P. Stratifying the patient at risk from coronary disease: new insights from the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J. 1990;119:712. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, Pitt B, Shi V, Hester A, et al. Benazepril plus Amlodipine or Hydrochlorothiazide for Hypertension in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakriset G, Briasoulis A, Dahlof B, Jamerson K, Weber MA, Kelly RY, et al. Comparison of Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide in high-risk patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(2):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.026. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyalomhe GBS, Omogbai EKI, Isah AO, Iyalomhe OOB, Dada FL, Iyalomhe SI. Efficacy of initiating therapy with amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide or their combination in hypertensive Nigerians. Clin Exptal Hypertens. 2013;35(8):620–627. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2013.776570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacourcière Y, Poirier L, Lefebvre J, Archambault F, Clèroux J, Boileau G. Antihypertensive effects of amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide in elderly patients with ambulatory hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8(12):1154–1159. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ram CVS, Ames RP, Applegate WB, Burris JF, Davidov ME, Mroczek WJ. Double-blind comparison of amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. Clin Cardiol. 1994;17:251–256. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960170506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadam P, Bhalerao S. Sample size calculation. Int J Ayurveda Res. 2010;1(1):55–57. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.59946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nwachukwu DC, Aneke EI, Obika LFO, Nwachukwu NZ. Investigation of antihypertensive effectiveness and tolerability of Hibiscus sabdariffa in mild to moderate hypertensive subjects in Enugu, South-east, Nigeria. American Journal of Phytomedicine and Clinical Therapeutics. 2015;19(2):148–152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO/ISH, author. Statement on hypertension. Management of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;17:151–183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajayi AA, Akintomide AO. The efficacy and tolerability of amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide in Nigerians with essential hypertension. J Natl Med Assoc. 1995;87:485–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otterstad JE, Ruilope LM. Treatment of hypertension in the very old. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2000 Nov;(114):10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvoet C, Gude F, Abellán J, Andrés MS, Olmos M, Pita L, Sánz D, Sarasa J, Bueno J, Herrera J, Marcias J, Sagastagoitia T, Ferro B, Vega A, Martinez J. A comparative evaluation of amlodipine and hydrochlorothiazide as monotherapy in the treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. Clin Drug Inves. 2000;19(5):317–326. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fadayomi MD, Akinroye KK, Ajao RO, Awosika LA. Monotherapy with nifedipine in adult blacks. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986;8:466–469. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liamis G, Milionis H, Elisaf M. Blood pressure drug therapy and electrolyte disturbances. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1572–1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nwachukwu DC, Aneke E, Nwachukwu NZ, Obika LFO, Nwagha UI, Eze AA. Effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa on blood pressure and electrolyte profile of mild to moderate hypertensive Nigerians: A comparative study with hydrochlorothiazide. Nig J Clin Pract. 2015;18:762–770. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.163278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]