ABSTRACT

The purpose of our study was to determine the frequency of patients who achieved a therapeutic drug level after receiving posaconazole (PCZ) delayed-release tablets (DRT) for prophylaxis or treatment of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) and to examine the effect of demographic traits and treatment characteristics on PCZ serum levels. A retrospective single-center study was conducted on high-risk inpatients at the University of Washington Medical Center (UWMC) that had received PCZ and obtained PCZ serum levels for either treatment or prophylaxis between 1 August 2014 and 31 August 2015. High-risk patients were defined as those undergoing chemotherapy for a primary hematologic malignancy and those undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) or solid organ transplantation. Serum trough concentrations of ≥700 μg/liter and ≥1,000 μg/liter were considered appropriate for prophylaxis and treatment, respectively. The most frequent underlying medical condition was a hematological malignancy (43/53, 81%). Twenty-six of 53 patients (49%) received PCZ for prophylaxis; the rest received PCZ for treatment. A total of 37/53 (70%) patients had PCZ serum levels of ≥700 μg/liter regardless of indication, including 22/26 (85%) that received PCZ for prophylaxis. Of the patients that received PCZ for treatment, only 12/27 (44%) had PCZ serum levels of ≥1,000 μg/liter. The odds of having therapeutic PCZ serum levels were not statistically different in patients with a weight of ≥90 kg, a diarrhea grade of ≥2, a mucositis grade of ≥2, or poor dietary intake. However, the odds of having therapeutic PCZ serum levels was 5.85 times higher in patients without graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) treatment than in those with GVHD treatment. Four patients on prophylaxis (15%) developed breakthrough IFIs, one of which had a subtherapeutic level. We concluded that the use of PCZ DRT provided adequate concentrations in only 70% of our patients and that recommended dosing may lead to insufficient levels in patients treated for IFIs. Lower concentrations noted among high-risk patients with GVHD suggest a need for prospective studies evaluating therapeutic drug monitoring and/or dose adjustments among these patients.

KEYWORDS: antifungal agents, drug levels

INTRODUCTION

Posaconazole (PCZ) is a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal agent with activity against a wide spectrum of fungi, including Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., and some Mucorales spp. PCZ is FDA approved for the prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) and used off-label for the treatment of IFIs. In clinical practice, PCZ is used primarily in high-risk oncology patients and immunocompromised populations, such as those with solid organ transplants, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML), or hematopoietic cell transplants (HCT) receiving either prophylaxis or treatment for IFIs (1, 2). PCZ is superior to other antifungal agents when used as prophylaxis against invasive aspergillosis and for reducing deaths related to IFIs in randomized clinical trials (3, 4). PCZ is commercially available as an oral suspension (OS), an oral delayed-release tablet (DRT), and an intravenous (i.v.) solution. The DRT formulation is reported to deliver more consistent and higher plasma drug concentrations and to be less dependent on gastric pH and food/nutritional supplements than the OS formulation (5). DRT has become the preferred antifungal agent at many centers.

The efficacy of PCZ for the prevention of IFIs was established without therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Although the correlation of concentration to clinical efficacy still remains unknown, there is an increasing body of evidence for PCZ TDM due to the drug's extensive pharmacokinetic variability (5, 6), and many clinicians still perform TDM of PCZ when used as treatment and as prophylaxis. Current guidelines also recommend TDM, even though the data about the variability of levels in patients using the DRT formulation is uncertain (7). A target concentration of 700 μg/liter for prophylaxis is widely cited and is derived from a post hoc analysis of two phase III clinical trials by Jang et al. (8). This study demonstrated that PCZ had a higher rate of clinical failure in patients achieving concentrations of <700 μg/liter in both study data sets, with no additional reduction in clinical failure rates seen above this concentration (8, 9). Many other studies have identified a trend toward an increased response rate with greater drug exposure (10). Recent consensus guidelines have recommended a target trough concentration at steady state of >700 μg/liter for prophylaxis and >1,000 μg/liter at steady state for treatment of IFIs to maximize efficacy (11, 12), although the number of patients that actually achieve concentrations within this therapeutic range and the clinical variables influencing drug levels remain poorly defined. Given the limited data on the DRT formulation, we set out to assess PCZ drug levels among high-risk patients receiving PCZ DRTs.

RESULTS

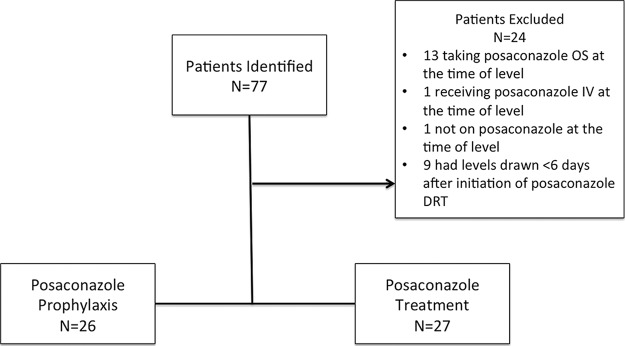

Of 77 patients initially evaluated for PCZ levels, 53 (69%) patients were eligible for inclusion in this study. Patients were excluded primarily for taking a different PCZ formulation (n = 14) or for the absence of PCZ steady-state trough levels (n = 10) (Fig. 1). The median age was 53 years (interquartile range [IQR], 41 to 63 years), with 53% being male. The median weight was 73 kg (IQR, 66 to 89 kg). The most frequent underlying medical condition was a hematological malignancy (43/53, 81%); of the 43 patients with a hematological malignancy, 19 (44%) had undergone HCT as part of their treatment. The majority of hematological malignancies consisted of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (30/53, 57%) (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Study design.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Patient demographica | Valueb for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 53) | Prophylaxis group (n = 26) | Treatment group (n = 27) | |

| Median age (IQR) (yr) | 53 (41, 63) | 53 (44, 63) | 56 (39, 65) |

| Male | 28 (53) | 15 (58) | 13 (48) |

| Median wt (IQR) (kg) | 73 (66, 89) | 73 (67, 100) | 72 (61, 88) |

| AML | 30 (57) | 17 (65) | 13 (48) |

| MDS | 4 (8) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) |

| ALL | 5 (9) | 1 (4) | 4 (15) |

| CLL | 2 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Lung transplant | 4 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 (15) |

| Myelofibrosis | 2 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| T-cell lymphoma | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Myelosarcoma | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Plasma cell leukemia | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Liver transplant | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Aspergilloma | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Transplant recipient | 19 (36) | 8 (31) | 11 (41) |

| Allogeneic | 16 (84) | 6 (75) | 10 (90) |

| Autologous | 3 (16) | 2 (25) | 1 (9) |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Unless otherwise indicated, the values are the number (%) of patients with the indicated characteristic.

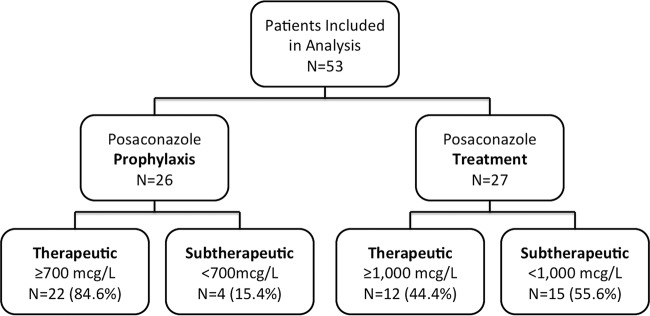

Of the 53 patients eligible for this study, 26 (49%) were receiving PCZ for prophylaxis and 27 (51%) were receiving PCZ for treatment of IFIs, with a median serum level of 1,192 μg/liter (IQR, 596 to 1,564 μg/liter). A total of 37/53 (70%) achieved PCZ serum levels of ≥700 μg/liter regardless of indication (22/26 [85%] of patients for prophylaxis and 15/27 [56%] of patients for treatment). The median serum level of patients receiving PCZ for prophylaxis was 1,293 μg/liter (IQR, 866 to 1,613 μg/liter). Of patients receiving PCZ for treatment, 12/27 (44%) achieved serum levels of ≥1,000 μg/liter (Fig. 2), with a median serum level of 745 μg/liter (IQR, 505 to 1,552 μg/liter). Therefore, 34/53 (64%) high-risk patients receiving PCZ DRT for prophylaxis or treatment of IFIs reached a therapeutic level.

FIG 2.

Patients included in per-protocol analysis.

Of the 4 patients receiving PCZ for prophylaxis who had PCZ serum levels of <700 μg/liter, 1 had a follow-up PCZ serum level 2 months later that was subsequently 2,026 μg/liter without dose adjustments; the 3 other patients had no additional testing. Among patients receiving PCZ for treatment with serum levels of <1,000 μg/liter, 4/15 (27%) were subsequently increased to PCZ at 400 mg daily and 2 of those had follow-up PCZ serum levels that increased from 335 to 621 μg/liter and 360 to 1,877 μg/liter, respectively. Ten of fifteen (67%) patients receiving PCZ for treatment with serum levels of <1,000 μg/liter remained on PCZ at 300 mg daily. A total of 6/10 (60%) of these patients had follow-up PCZ serum levels, and only one patient had a therapeutic serum level of 2,880 μg/liter. Of the 26 patients receiving PCZ for prophylaxis, 4 (15%) developed breakthrough IFIs (3 with Mucorales spp., and 1 with Fusarium spp.). All 4 patients had underlying AML, and only one had a subtherapeutic PCZ serum level of 542 μg/liter.

The association between PCZ serum levels and demographic variables was consistent between the simple and multivariable logistic regression models. The results of all models are presented in Table 2. The likelihood of reaching a therapeutic serum level was not statistically different when patients were assessed by weight, diarrhea, mucositis, or diet. However, patients not receiving treatment for GVHD had higher odds of achieving a therapeutic serum level than those receiving GVHD treatment (odds ratio [OR], 5.85; 95% CI, 1.09 to 31.5; P = 0.04) (Table 2). The odds of achieving therapeutic serum levels was also higher among patients receiving PCZ for prophylaxis than among those receiving PCZ for treatment (OR, 9.67; 95% CI, 2.07 to 45.09; P = 0.004) (Table 2). Stratification of these patient characteristics by prophylaxis or treatment is presented in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Simple and multivariable logistic regression of clinical characteristicsa

| Patient characteristic | Simple logistic regression |

Multivariable logistic regression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Group | ||||

| Prophylaxis | 6.87 (1.86, 25.43) | 0.004 | 9.67 (2.07, 45.09) | 0.004 |

| Treatment | Reference | Reference | ||

| Wt | ||||

| <90 kg | 1.38 (0.37, 5.14) | 0.63 | 1.73 (0.30, 10.05) | 0.54 |

| ≥90 kg | Reference | Reference | ||

| Diarrheab | ||||

| Grade of <2 | 0.99 (0.28, 3.55) | 0.99 | 0.71 (0.14, 3.56) | 0.68 |

| Grade of ≥2 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Mucositisc | ||||

| Grade of <2 | Reference | 0.64 | Reference | 0.89 |

| Grade of ≥2 | 1.74 (0.17, 18.01) | 1.21 (0.08, 18.93) | ||

| Dietd | ||||

| Poor | Reference | 0.76 | Reference | 0.50 |

| Normal | 1.2 (0.38, 3.81) | 1.67 (0.38, 7.35) | ||

| GVHD treatmente | ||||

| No | 4.22 (1.13, 15.72) | 0.03 | 5.85 (1.09, 31.5) | 0.04 |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. The outcome is therapeutic serum levels (versus subtherapeutic levels) defined as ≥700 μg/liter in the prophylaxis group or ≥1,000 μg/liter in the treatment group.

Diarrhea of grade 2 is defined as an increase of four to six stools per day over baseline or a moderate increase in ostomy output compared to the baseline, assuming a baseline of one stool/day and with normal consistency.

Mucositis of grade 2 is defined as moderate pain, not interfering with oral intake, with modified diet indicated.

Poor diet is defined as ≤50% of reported diet intake, on total parenteral nutrition, or on meal supplementation 4 days prior to the date that the PCZ serum level was determined.

GVHD treatment is defined as intensive immunosuppressive therapy consisting of either high-dose corticosteroids (≥1 mg/kg/day) for patients with acute GVHD or ≥0.8 mg/kg every other day for patients with chronic GVHD, antithymocyte globulin, or a combination of two or more immunosuppressive agents or types of treatment.

TABLE 3.

Patient characteristics stratified by group

| Patient characteristic | Valuea for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 53) | Prophylaxis group (n = 26) | Treatment group (n = 27) | |

| Wt < 90 kg | 41 (77) | 19 (73) | 22 (81) |

| Wt ≥ 90 kg | 12 (23) | 7 (27) | 5 (19) |

| Diarrhea grade < 2 | 39 (74) | 18 (69) | 21 (78) |

| Diarrhea grade ≥ 2 | 14 (26) | 8 (31) | 6 (22) |

| Mucositis grade < 2 | 49 (92) | 24 (92) | 25 (93) |

| Mucositis grade ≥ 2 | 4 (8) | 2 (8) | 2 (7) |

| Poor diet | 32 (60) | 17 (65) | 15 (56) |

| Normal diet | 21 (40) | 9 (35) | 12 (44) |

| No GVHD treatment | 40 (75) | 20 (77) | 20 (74) |

| GVHD treatment | 13 (25) | 6 (23) | 7 (26) |

All values are the number (%) of patients with the indicated characteristic.

DISCUSSION

PCZ is a broad-spectrum antifungal used for the prophylaxis or treatment of IFIs. The PCZ DRT formulation is reported to have improved absorption and less pharmacokinetic variability regardless of fasting/fed conditions or differences in gastric pH or gastrointestinal motility than the PCZ OS formulation (20). These improvements are purported to reduce the need to remove acid-suppressing therapies and encourage high-fat meals, given the decreased variability in PCZ serum levels. However, PCZ serum levels can still be quite variable, and consensus guidelines and experts have recommended a target level of 700 μg/liter for prophylaxis and a target level of 1,000 μg/liter for treatment of IFIs (11, 12).

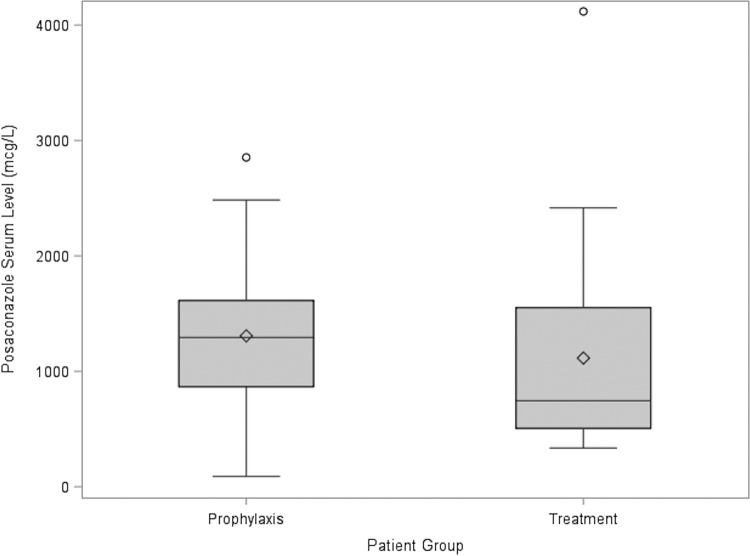

The population in this study included mainly AML patients and was evenly balanced between patients receiving PCZ for either prophylaxis or treatment of IFIs. At UWMC, trough levels are routinely obtained in patients 6 to 7 days after initiation of PCZ therapy for treatment of IFIs to ensure steady state. The median PCZ serum level was 1,192 μg/liter (IQR, 596 to 1,564 μg/liter), suggesting that a good proportion of patients were not reaching serum levels of ≥700 μg/liter (Fig. 3). In this study, only 70% of all patients receiving PCZ had serum levels of ≥700 μg/liter. Even more concerning is that half of the patients receiving PCZ DRT for the treatment of IFIs had subtherapeutic levels (≤1,000 μg/liter) and, despite follow-up testing, continued to have subtherapeutic levels. In comparison, a historical cohort (n = 33) receiving PCZ OS from our institution between January 2007 and November 2010 for the treatment of suspected or identified IFIs showed a mean, median, and range of PCZ concentrations of 730 μg/liter, 580 μg/liter, and 0 to 2,080 μg/liter, respectively. These results reflect the improvement in bioavailability and attainment of higher plasma drug concentrations with the PCZ DRT formulation (14). These results are based on recommended levels from available guidelines (11, 12). If other standards are used, such as ≥1,250 μg/liter as suggested by others, then subtherapeutic rates would have been higher (15).

FIG 3.

Posaconazole serum concentrations The circles represent outliers (more than 1.5 times the IQR), the diamonds represent the means for each group, the boxes represent the IQR 25th/75th percentiles, the horizontal lines in the box represent the medians for each group, and the lines extending from the boxes represent the ranges of the data (excluding outliers).

Other studies looking at patients with hematological malignancies (mainly AML) receiving PCZ DRT for IFI prophylaxis found consistently therapeutic levels (≥700 μg/liter) with a mean PCZ serum level of 1,320 μg/liter and questioned the need for therapeutic drug monitoring when using PCZ DRT for IFI prophylaxis (13). Previous studies have also suggested that patients who weighed >90 kg or who had significant diarrhea may be more likely to have lower levels (16), but the data in this study do not support these findings. Changes in mucosal and gut integrity have affected PCZ concentrations in patients taking PCZ OS and may theoretically affect PCZ DRT concentrations, but various studies have found that the presence of gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GI GVHD), mucositis, or diarrhea did not affect the ability of patients to achieve PCZ target concentrations (13). Our study results are consistent with the findings by Pham et al. showing that the odds of achieving therapeutic PCZ serum levels were weighted toward patients without GVHD (13). Future studies are needed to further elucidate this relationship, and in the meantime, TDM of PCZ may be warranted in this patient population.

Additionally, for patients receiving PCZ for treatment of IFIs, our data suggest that dosing of PCZ at 300 mg daily may be suboptimal since only one (1/6, 17%) participant had a therapeutic level on follow-up serum testing. Despite a lack of guidance on how to make subsequent dose adjustments following subtherapeutic serum levels, a single-center study recently published their experience with dose increases from 300 mg to 400 mg daily with follow-up levels suggestive of nonlinear pharmacokinetics with a minimal increase in toxicities (17). Our study revealed that dose increases to 400 mg of PCZ daily in patients receiving PCZ for treatment led to respective increases in PCZ serum levels, confirming the results of this single-center study; such findings require further investigation.

As with any retrospective observational chart review, this study has several limitations. Patients were not randomized, and investigators were not blinded. Inherent bias may have been present in patients who had PCZ serum levels determined, since these patients may have been suspected to be failing therapy, having breakthrough infections, having a higher risk for poor compliance, or being at risk for poor absorption. Therefore, having PCZ serum levels determined may in itself been a predictor of low serum levels. There may also have been information, particularly regarding diet or diarrhea, that was somewhat subjective in medical charting. Diarrhea is a common occurrence in all hospitalized patients, and although only diarrhea of grade ≥2 was assessed, the reported results may not reflect the patients' true output. Medication adherence was assumed when patients were admitted to UWMC and already on PCZ, but given patient compliance and the high-cost of PCZ, this may have affected PCZ serum levels that were determined early during admission for patients who were treated as outpatients.

Finally, this study could only examine the surrogate marker of PCZ serum concentrations and did not evaluate whether consistent and higher concentrations translated into clinically relevant outcomes of preventing morbidity or mortality from IFIs. Future studies can be directed to this area.

Conclusion.

In this single-center study, PCZ DRTs provided adequate concentrations in 85% of high-risk patients receiving PCZ for prophylaxis and in <50% of high-risk patients receiving PCZ for treatment of IFIs. The lower odds of achieving a therapeutic serum concentration among patients with GVHD suggest a need for prospective studies evaluating therapeutic drug monitoring and/or dose adjustments among these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the frequency at which high-risk patients receiving PCZ DRT for prophylaxis and treatment of IFIs reached a therapeutic level. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the impact of dose adjustments, diarrhea, weight, nutritional status, mucositis, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) on PCZ serum levels and to estimate the incidence of breakthrough IFIs in patients receiving PCZ DRT for prophylaxis.

This retrospective, observational, single-center study was conducted at the University of Washington Medical Center (UWMC) and approved by the UWMC's Institutional Review Board. To be eligible, patients were required to be ≥18 years old, to have been admitted as an inpatient to UWMC, be receiving PCZ DRT for either treatment or prophylaxis between 1 August 2014 and 31 August 2015, and to have associated PCZ serum levels. Patients receiving <6 days of treatment or other PCZ formulations were excluded. PCZ serum levels were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) by the Laboratory Medicine Department. The method uses protein precipitation with zinc sulfate and acetonitrile. Deuterium-labeled PCZ (Cerilliant) is used as an internal standard. Chromatographic separation is achieved by gradient elution through an Ascentis Express C18 column (Supelco; Sigma-Aldrich), and mass spectrometric detection is done with a Quattro micro API system (Waters). The assay was determined to be linear for concentrations between 0.05 and 10 μg/ml with an intraday variability of 2.2 to 2.5% coefficient of variation (% CV) and an interday variability of 2.3 to 3.2% CV at 0.7 to 5.1 mg/ml. The lower limit of quantification (20% CV) was determined to be 0.01 μg/ml. Transitions monitored include 701.20/614.25 m/z and 701.20/683.30 m/z for the endogenous standard and 705.25/618.25 m/z and 705.25/687.30 m/z for the internal standard. Therapeutic levels were defined as trough concentrations of ≥700 μg/liter at steady state for prophylaxis and ≥1,000 μg/liter at steady state for treatment of IFIs. For patients with multiple serum concentrations, only the first valid serum concentration was included for analyses. All clinical and demographic data were extracted from patients' electronic medical records.

A mucositis grade of ≥2 and a diarrhea grade of ≥2 were evaluated at any time during PCZ therapy and defined according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.03 (CTCAE) assuming one baseline stool per day in all patients (18). Nutritional status was assessed up to 4 days prior to PCZ serum level determination, and poor diet was defined as ≤50% normal intake or the use of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or meal supplements (e.g., Ensure, Boost). GVHD treatment was defined as intensive immunosuppressive therapy consisting of either high-dose corticosteroids for GVHD (≥1 mg/kg/day for patients with acute GVHD or ≥0.8 mg/kg every other day for patients with chronic GVHD), antithymocyte globulin, or a combination of two or more immunosuppressive agents for GVHD at any point during PCZ therapy. In patients with breakthrough fungal infection during PCZ prophylaxis, IFI was classified as proven, probable, or possible according to the 2008 modified European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) guidelines (19).

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were summarized as proportions for categorical variables and by medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Simple and multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate which, if any, demographic traits were associated with achieving therapeutic serum levels. Therapeutic status was defined as serum concentration levels of at least 700 μg/liter for patients in the prophylaxis group and at least 1,000 μg/liter for patients in the treatment group. Patients who did not satisfy these criteria were considered subtherapeutic. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Statistical software 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). A significance level of a 2-sided 0.05 was used for all analyses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Mary Redman to this paper.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Steven A. Pergam has received research support from, and been a consultant to, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. and Optimer/Cubist Pharmaceuticals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, Boeckh MJ, Ito JI, Mullen CA, Raad II, Rolston KV, Young JA, Wingard JR. 2011. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 52:e56–e93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2016. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections (version 1.2016). http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/infections.pdf Accessed 16 May 2016.

- 3.Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, Helfgott D, Holowiecki J, Stockelberg D, Goh YT, Petrini M, Hardalo C, Suresh R, Angulo-Gonzalez D. 2007. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med 356:348–359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullmann AJ, Lipton JH, Vesole DH, Chandrasekar P, Langston A, Tarantolo SR, Greinix H, Morais de Azevedo W, Reddy V, Boparai N, Pedicone L, Patino H, Durrant S. 2007. Posaconazole or fluconazole for prophylaxis in severe graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 356:335–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merck & Co., Inc. 2015. Noxafil (posaconazole) product information. Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolton MJ, Ray JE, Chen SC, Ng K, Pont L, McLachlan AJ. 2012. Multicenter study of posaconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: exposure-response relationship and factors affecting concentration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5503–5510. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00802-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant AM, Slain D, Cumpston A, Craig M. 2011. A post-marketing evaluation of posaconazole plasma concentrations in neutropenic patients with haematological malignancy receiving posaconazole prophylaxis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 37:266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang SH, Colangelo PM, Gobburu JV. 2010. Exposure-response of posaconazole used for prophylaxis against invasive fungal infections: evaluating the need to adjust doses based on drug concentrations in plasma. Clin Pharmacol Ther 88:115–119. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. 2016. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 63:e1–e60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashbee HR, Barnes RA, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, Gorton R, Hope WW. 2014. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of antifungal agents: guidelines from the British Society for Medical Mycology. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:1162–1176. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis R, Brüggemann R, Padoin C, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Groll A, Johnson E, Arendrup M. 2015. Triazole antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring. ECIL 6 meeting, 12 September 2015. Retrieved from https://www.ebmt.org/Contents/Resources/Library/ECIL/Documents/2015%20ECIL6/ECIL6-Triazole-TDM-07-12-2015-Lewis-R-et-al.pdf.

- 12.Chau MM, Kong DC, van Hal SJ, Urbancic K, Trubiano JA, Cassumbhoy M, Wilkes J, Cooper CM, Roberts JA, Marriott DJ, Worth LJ. 2014. Consensus guidelines for optimising antifungal drug delivery and monitoring to avoid toxicity and improve outcomes in patients with haematological malignancy, 2014. Intern Med J 44:1364–1388. doi: 10.1111/imj.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pham AN, Bubalo JS, Lewis JS II. 2016. Comparison of posaconazole serum concentrations from haematological cancer patients on posaconazole tablet and oral suspension for treatment and prevention of invasive fungal infections. Mycoses doi: 10.1111/myc.12452 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slezak K, Xie H, Fredricks D, Pottinger PS, Jain R. 2011. Therapeutic posaconazole concentrations are associated with improved survival, abstr M-287. Abstr 51st Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh TJ, Raad I, Patterson TF, Chandrasekar P, Donowitz GR, Graybill R, Greene RE, Hachem R, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Langston A, Louie A, Ribaud P, Segal BH, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, White CS, Corcoran G, Gogate J, Krishna G, Pedicone L, Hardalo C, Perfect JR. 2007. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of conventional therapy: an externally controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 44:2–12. doi: 10.1086/508774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miceli MH, Perissinotti AJ, Kauffman CA, Couriel DR. 2015. Serum posaconazole levels among haematological cancer patients taking extended release tablets is affected by body weight and diarrhoea: single centre retrospective analysis. Mycoses 58:432–436. doi: 10.1111/myc.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pham AN, Bubalo JS, Lewis JS II. 2016. Posaconazole tablet formulation at 400 milligrams daily achieves desired minimum serum concentrations in adult patients with a hematologic malignancy or stem cell transplant. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:6945–6947. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01489-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute. 29 May 2009. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, v4.0. NIH publication 09-7473; NCI, NIH, DHHS: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiederhold NP. 2015. Pharmacokinetics and safety of posaconazole delayed-release tablets for invasive fungal infections. Clin Pharmacol 8:1–8. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S60933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]