Abstract

Obturator hernia is a rare clinical condition that causes intestinal obstruction. Recent reports have suggested that laparoscopic repair may be useful for incarcerated obturator hernia in select patients. The patient was a 64-year-old female who presented to our emergency department with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed an incarcerated obturator hernia on her right side, without apparent findings of irreversible ischaemic change or perforation. She had a previous history of cardiovascular surgery and was taking an anticoagulant medication. We performed a reduction of the incarcerated intestine. After heparin displacement, laparoscopic repair was electively performed. During laparoscopy, an occult obturator hernia was found on the left side. We repaired the bilateral obturator hernia using a mesh prosthesis. Elective laparoscopic repair after reduction might be a useful procedure for incarcerated obturator hernias in those patients without findings of irreversible ischaemic change or perforation.

INTRODUCTION

Obturator hernia is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction and most frequently occurs in elderly, thin and multiparous females [1–3]. The incidence of obturator hernias have been reported as 0.05–1.4% of all hernias [1, 2]. The diagnosis is often delayed due to difficulty in its detection [1–3]. In addition, patients with delayed diagnosis often need intestinal resection and have a high mortality rate [1–3]. Recent reports have suggested that laparoscopic repair may be feasible for incarcerated obturator hernias [4, 5]. Here, we report on a case of an incarcerated obturator hernia that was successfully treated by elective laparoscopic repair after reducing the incarceration.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 64-year-old female who presented to our emergency department with a complaint of abdominal pain. A physical examination revealed a moderately distended abdomen without signs of peritoneal irritation. She had a previous history of cardiovascular surgery and had taken warfarin. Her body mass index was 14.88 kg/m2. Laboratory data did not show specific abnormal data, including a white blood cell count of 8800/μl and a C-reactive protein level of 0.06 mg/dl.

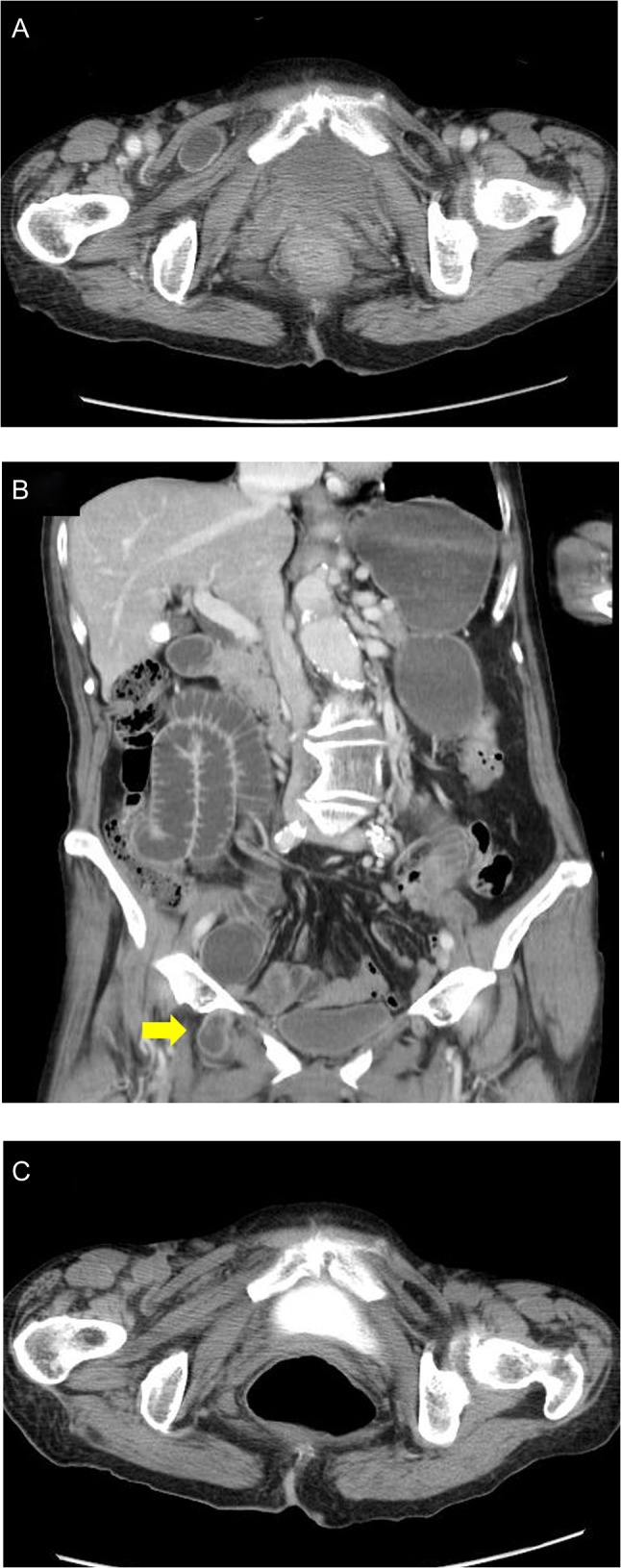

A computed tomography (CT) image revealed an incarcerated obturator hernia on the right side (Fig. 1A) and the oral side intestine was markedly distended. The bowel wall of the incarcerated intestine showed contrast enhancement but did not show irreversible ischaemic change or perforation (Fig. 1B). We did not detect obturator hernia on the left side (Figs 1A and 1B). We then successfully reduced the incarcerated intestine by using an echocardiography probe. After reduction (Fig. 1C), her abdominal symptoms improved. On the seventh day following admission under heparin displacement, we performed laparoscopic transabdominal peritoneal repair of the obturator hernia. After confirming the obturator hernia on the right side, we cut the peritoneum on the Cooper ligament, and the preperitoneal space around the obturator foramen was dissected (Fig. 2A and B). A prosthetic mesh (6 × 7 cm in size) was then inserted into the dissected space (Fig. 2C). Tacking the mesh onto the Cooper ligament, the obturator foramen was covered by the mesh maintaining a 2–3 cm margin, and the peritoneum was closed with sutures (Fig. 2D). During laparoscopy, an occult obturator hernia on the left side was detected. Subsequently, the left side obturator hernia was repaired by the same method (Fig. 3A–D). A continuous intravenous infusion of heparin and oral warfarin was started on the first postoperative day. The patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day with an uneventful postoperative course.

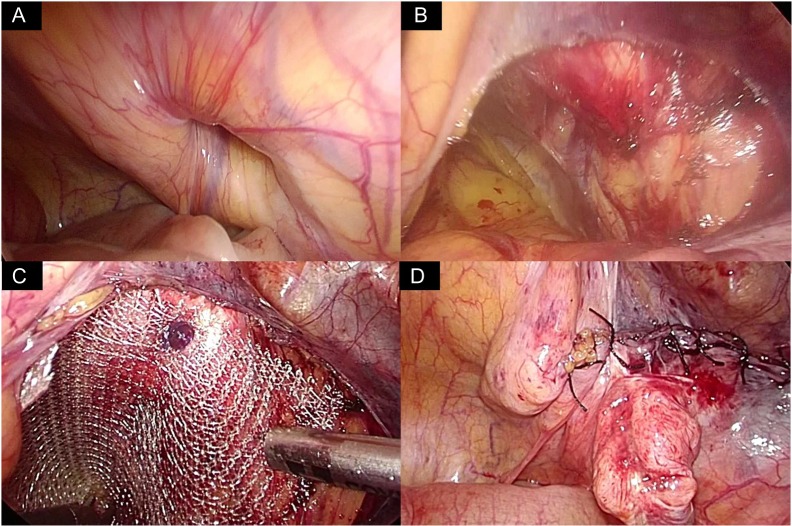

Figure 1:

(A) Incarcerated obturator hernia on the right side was confirmed by CT image. Bowel wall of the incarcerated intestine showed contrast enhancement without findings of irreversible ischaemic change or perforation. (B) Coronal plane of CT image, before reduction. The oral side intestine was markedly distended and contrast enhanced. (C) Reduction of the incarcerated intestine was confirmed by CT image.

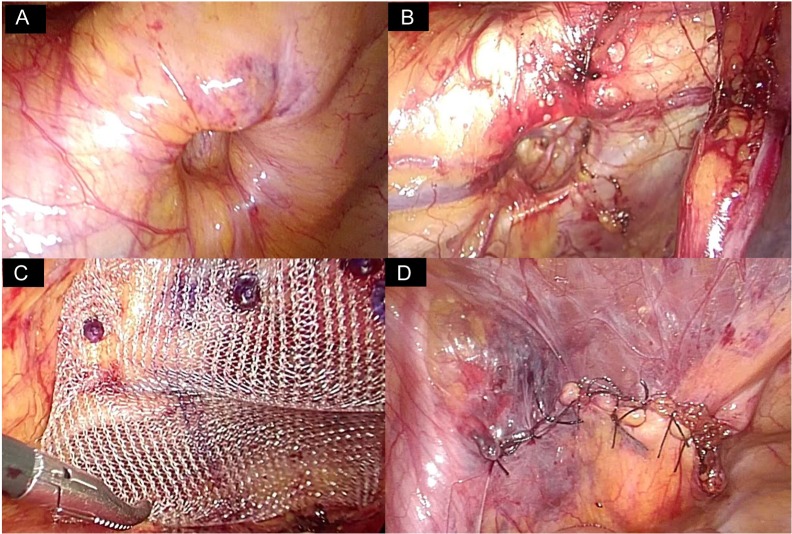

Figure 2:

Repair of the right side obturator hernia. (A) Obturator hernia on the right side was confirmed. (B) The peritoneum on the Cooper ligament was cut and the preperitoneal space around the obturator foramen was dissected. (C) A prosthetic mesh (6 × 7 cm in size) was inserted in the dissected space and the mesh was tacked onto the Cooper ligament. The obturator foramen was covered by the mesh maintain a 2–3 cm margin. (D) The peritoneum was closed with sutures.

Figure 3:

Repair of the left side obturator hernia. (A) Obturator hernia on the left side was detected during laparoscopy. (B) The peritoneum on the Cooper ligament was cut and the preperitoneal space around the obturator foramen was dissected. (C) A prosthetic mesh (6 × 6 cm in size) was inserted in the dissected space and the mesh was tacked onto the Cooper ligament. The obturator foramen was covered by the mesh maintaining a 2–3 cm margin. (D) The peritoneum was closed with sutures.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we presented a case of incarcerated obturator hernia treated by elective laparoscopic repair after reduction of the incarcerated intestine. In addition to being less invasive, the usefulness of elective laparoscopic for repairing an incarcerated obturator hernia, as suggested in the present case, can be summarized as follows: (i) surgeons could share a better surgical field compared with those of an emergency operation due to intestinal decompression; (ii) the detection and repair of an occult obturator hernia on the contralateral side may be more feasible due to the better surgical field and (iii) patients who are at risk for emergency operation due to comorbidities can have more time to prepare for the operation.

Recently, the feasibility of the laparoscopic repair for obturator hernia has been reported [3, 4]. The procedure includes a simple peritoneal closure, reconstruction using a tissue flap, coverage of adjacent tissue and permanent prosthesis [3]. However, not all patients with an incarcerated obturator hernia will achieve laparoscopic surgery without conversion [4, 5]. The reasons for conversion may include iatrogenic bowel injury, inadequate visualization and the need for bowel resection [6, 7]. Therefore, elective surgery after reducing the incarcerated intestine is reasonable to obtain a good surgical field, complete laparoscopic surgery and avoid perioperative complications.

According to Susmallian, 20 of the 293 (6.82%) of patients who underwent repair of a bilateral or recurrent inguinal hernia had an occult obturator hernia; further, 14 of these 20 patients had a bilateral lesion [8]. These data suggested that surgeons should check for the presence of an obturator hernia on the contralateral side. Occult obturator hernia found during surgery is the indication for repairing at the same session in order to avoid future complications and surgery [8]. However, at an emergency surgery in which patients are at a high risk of complications, it is often a burden for surgeons to check for and repair an occult illness. It seems that elective surgery is a more reasonable setting for checking for and repairing occult contralateral obturator hernias.

Obturator hernias frequently occur in the elderly female patients [1, 2, 8]. In this population, many patients have taken anticoagulant drugs. A previous report suggested that patients with anticoagulant drugs had a 4-fold higher risk for postoperative bleeding following inguinal hernia repair [9]. Heparin displacement is a standard method for minimizing the risk of bleeding post-surgery. Therefore, from the standpoint of postoperative bleeding, a reduction of the incarcerated intestine followed by elective surgery is superior to emergency surgery.

There are serious limitations in the reduction of incarcerated intestine. If the incarcerated intestine has irreversible ischaemic change or perforation, it is contraindicated to perform the reduction, and the patient will require an emergency operation. Thus, elective laparoscopic repair after such a reduction should be limited to patients without findings of irreversible ischaemic change. In patients with an incarcerated obturator hernia, symptoms often develop in stages, and patients visit the emergency department a few days after onset [2, 4, 5]. Therefore, to accurately make a diagnosis and assess the presence of irreversible ischaemic change or perforation, which implies a requirement of emergency surgery, is important. CT imaging is considered the gold standard for diagnosing an obturator hernia with high sensitivity and specificity [1, 2, 5]. In addition to the general condition and abdominal symptom of patients, CT imaging provides useful information for assessing ischaemic change of the intestine [10]. Reduced enhancement of bowel wall and elevation of bowel wall attenuation in an unenhanced image are highly predictive of ischaemia [10]. In our institution, we make it a rule to perform reduction only in the patients without these CT findings with localized abdominal symptoms. If the abdominal symptoms of the patients after reduction did not improved or worsened, emergency operation should be considered.

In conclusion, the present case suggests that elective laparoscopic repair following reduction might be a useful strategy for incarcerated obturator hernias in those patients without findings of irreversible ischaemic change or perforation.

FUNDING

No authors have direct or indirect commercial and financial incentives associated with publishing the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CONSENT

The patient discussed in this case report provided informed consent for publishing the information in this report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chang SS, Shan YS, Lin YJ, Tai YS, Lin PW. A review of obturator hernia and a proposed algorithm for its diagnosis and treatment. World J Surg 2005;29:450–4. PMID: 15776293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petrie A, Tubbs RS, Matusz P, Shaffer K, Loukas M. Obturator hernia: anatomy, embryology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Anat 2011;24:562–9. doi:10.1002/ca.21097. PMID: 21322061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hayama S, Ohtaka K, Takahashi Y, Ichimura T, Senmaru N, Hirano S. Laparoscopic reduction and repair for incarcerated obturator hernia: comparison with open surgery. Hernia 2015;19:809–14. doi:10.1007/s10029-014-1328-3. PMID: 25504450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu J, Zhu Y, Shen Y, Liu S, Wang M, Zhao X, et al. The feasibility of laparoscopic management of incarcerated obturator hernia. Surg Endosc 2017;31:656–60. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-5016-5. PMID: 27287915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leitch MK, Yunaev M. Difficult diagnosis: strangulated obturator hernia in an 88-year-old woman. BMJ Case Rep 2016;doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-215428. PMID: 27358098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ghosheh B, Salameh JR. Laparoscopic approach to acute small bowel obstruction: review of 1061 cases. Surg Endosc 2007;21:1945–9. PMID: 17879114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O’Connor DB, Winter DC. The role of laparoscopy in the management of acute small-bowel obstruction: a review of over 2,000 cases. Surg Endosc 2012;26:12–7. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1885-9. PMID: 21898013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Susmallian S, Ponomarenko O, Barnea R, Paran H. Obturator hernia as a frequent finding during laparoscopic pelvic exploration: a retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4102.doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004102. PMID: 27399109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Köckerling F, Roessing C, Adolf D, Schug-Pass C, Jacob D. Has endoscopic (TEP, TAPP) or open inguinal hernia repair a higher risk of bleeding in patients with coagulopathy or antithrombotic therapy? Data from the Herniamed Registry. Surg Endosc 2016;30:2073–81. doi:10.1007/s00464-015-4456-7. PMID: 26275547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kohga A, Kawabe A, Yajima K, Okumura T, Yamashita K, Isogaki J, et al. CT value of the intestine is useful predictor for differentiate irreversible ischaemic changes in strangulated ileus. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1227-z. PMID: 28647770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]