Abstract

Objective

Describe the process of enacting and defending strong tobacco packaging and labelling regulations in Uruguay amid Philip Morris International’s (PMI) legal threats and challenges.

Methods

Triangulated government legislation, news sources and interviews with policy-makers and health advocates in Uruguay.

Results

In 2008 and 2009, the Uruguayan government enacted at the time the world’s largest pictorial health warning labels (80% of front and back of package) and prohibited different packaging or presentations for cigarettes sold under a given brand. PMI threatened to sue Uruguay in international courts if these policies were implemented. The Vazquez administration maintained the regulations, but a week prior to President Vazquez’s successor, President Mujica, took office on 1 March 2010 PMI announced its intention to file an investment arbitration dispute against Uruguay in the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes. Initially, the Mujica administration announced it would weaken the regulations to avoid litigation. In response, local public health groups in Uruguay enlisted former President Vazquez and international health groups and served as brokers to develop a collaboration with the Mujica administration to defend the regulations. This united front between the Uruguayan government and the transnational tobacco control network paid off when Uruguay defeated PMI’s investment dispute in July 2016.

Conclusion

To replicate Uruguay’s success, other countries need to recognise that strong political support, an actively engaged local civil society and financial and technical support are important factors in overcoming tobacco industry’s legal threats to defend strong public health regulations.

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1990s, the tension between trade and tobacco control has escalated1 as new legal rules concerning intellectual property and foreign investment have enabled investors (including tobacco companies) to challenge domestic public health policies in international trade and investment arbitration courts.2–4 Tobacco companies lobbied states in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and World Trade Organization (WTO) to file trade disputes against other member states’ tobacco control policies.5,6 Subsequently, tobacco companies directly challenged public health policies using investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms in trade and investment agreements7 and used the threat of legal action8 to dissuade governments from implementing tobacco control policies.9

Partially in response to trade challenges, tobacco control advocates formed a transnational tobacco control network, consisting of health advocates, health organisations, academics, lawyers and donors to increase exchanges of information and services.10 This network combines characteristics of global civil society,11 epistemic communities12,13 and advocacy networks.14 This network supported the creation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)15 and assisted governments in implementing it,16–19 which has accelerated the adoption of tobacco control regulations,20–23 including pictorial health warning labels (HWLs) on cigarette packages.24 The fact that the FCTC does not clearly prioritise health over trade1,25 forced this network to adapt and combat emerging pressures of trade on tobacco control.

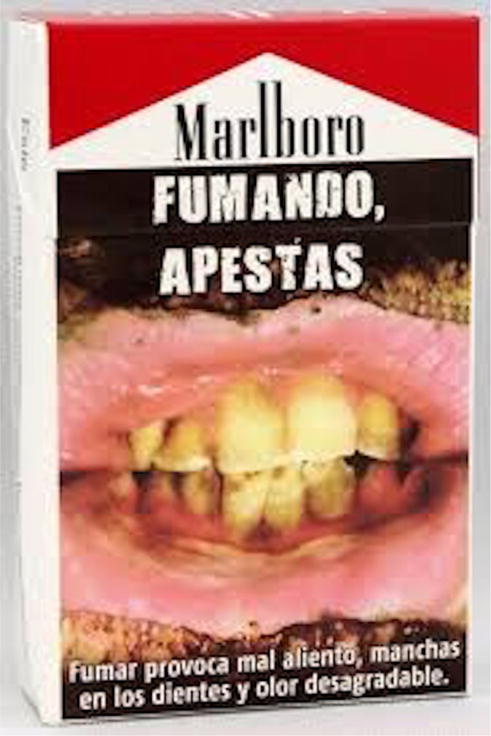

In 2004, Dr Tabaré Vazquez, an oncologist, was elected president and made reducing tobacco consumption a high priority. Supported by strong local advocates, Uruguay became the first Latin American country to establish 100% smokefree environments in all workplaces and public places,26 prohibit misleading descriptors on cigarette packages and adopt pictorial HWLs covering 50% of the front and back of the package27 (table 1). As in other countries,28–30 Philip Morris International’s (PMI) Uruguayan subsidiary Abal Hermanos (Abal) responded to the prohibition by colour-coding cigarette packages (eg, replacing Marlboro Lights with yellow Marlboro packages). In 2008 and 2009, the Uruguayan government responded by implementing the world’s strongest (at the time) tobacco packaging and labelling regulations, requiring pictorial HWLs covering 80% of the front and back of the package31 (figure 1) and that cigarette brands be sold in a single pack presentation.32 (The single pack presentation permitted only one variant of each cigarette brand which prohibited the colour-coding of ‘light’ and ‘mild’28–30,33 or menthol33 variants). PMI then threatened and sued Uruguay in domestic and international courts. With strong political support, an actively engaged local civil society and the transnational tobacco control network that provided financial and technical support, Uruguay overcame these legal challenges and defended its regulations, serving as a model for future public health successes.

Table 1.

Timeline of packaging and labelling regulations in Uruguay (2004–2016)

| Date | Actor | Event | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | Tobacco industry | Civil society | ||

| 31 October 2004 | X | Tabaré Vazquez is elected president of Uruguay. | ||

| 31 May 2005 | X | Health Ministry issues health decree N. 35 requiring cigarette packages to be sold without misleading descriptors and pictorial HWLs covering 50% of both sides of the package.27 | ||

| 2006–2008 | X | Abal Hermanos (PMI) ignores law by continuing to sell color-coded cigarette packages.44 | ||

| 6 March 2008 | X | Congress enacts Law 18.256 to further institutionalise packaging and labelling policies.112 | ||

| 18 August 2008 | X | Health Ministry issues Public Ordinance N. 514 requiring each cigarette brand to have a single presentation.32 | ||

| 10 September 2008 | X | Abal sends letter to Health Ministry arguing Ordinance N. 514 violates the Uruguayan constitution and their investment rights under international treaties.36 | ||

| 23 September 2008 | X | Abal sends another letter to Health Ministry arguing Ordinance N. 514 violates treaties.36 | ||

| 26 December 2008 | X | Abal sends another letter to Health Ministry arguing Ordinance N. 514 violates treaties.36 | ||

| 3 February 2009 | X | Abal sends another letter to Health Ministry arguing Ordinance N. 514 violates treaties.37 | ||

| 9 February 2009 | X | Abal files a request in local courts for injunction to suspend Ordinance N. 514.58 | ||

| 14 February 2009 | X | Ordinance N. 514 comes into effect.32 | ||

| 18 February 2009 | X | Civil court denies Abal’s request for an injunction on procedural grounds.85 | ||

| 27 April 2009 | X | Civil court of appeals rejects Abal’s appeal on procedural grounds.85 | ||

| 9 June 2009 | X | Abal files an annulment action with the Administrative Court seeking the annulment of Article 3 (requiring single brand presentation) and suspension of Ordinance N. 514.59 | ||

| 15 June 2009 | X | President Vazquez issues executive decree N. 287 to increase pictorial HWLs from covering 50% to 80% of the front and back of the package.31 | ||

| 25 June 2009 | X | Abal sends threatening letter to Health Ministry arguing Decree N. 287 violates the Uruguayan constitution and their investment rights under international treaties.38 | ||

| 11 September 2009 | X | Abal files annulment action with the Administrative Court that executive decree N. 287 grants the executive branch unlimited power to impose restrictions on individual rights.61 | ||

| 12 December 2009 | X | Decree N. 287 comes into effect.31 | ||

| 19 February 2010 | X | PMI pays a non-refundable fee of $25 000 to file an investment dispute against Uruguay in ICSID under a 1991 Uruguay-Switzerland BIT to challenge the regulations.63 | ||

| 19 February 2010 | X | Members of local tobacco control organisations CIET and SUT publish opinion-editorials in local newspapers denouncing PMI’s attempt to intimidate the government.69,70 | ||

| 1 March 2010 | X | President Mujica enters office as President of Uruguay. | ||

| March 2010 | X | Local health groups inform international health groups the government’s willingness to defend regulations but that they lack legal and financial capacity to fight PMI.44,49 | ||

| 26 March 2010 | X | The ICSID Secretary-General determines PMI’s challenge falls within the jurisdiction of the Centre and registers the investment dispute.67 | ||

| April–July 2010 | X | PMI privately meets with top government officials about amending the regulations.73 | ||

| June–July 2010 | X | CIET members learn that PMI is privately negotiating with the government to weaken the regulations and warn against the possibility of weakened regulations in the media.44,49 | ||

| 29 June 2010 | X | CIET writes a letter to former President Vazquez informing him that the Mujica government is privately negotiating with PMI to weaken the regulations.44 | ||

| 16 July 2010 | X | TFK coordinates letter from international groups to President Mujica to offer legal support, requesting the administration not settle with PMI by weakening the regulations.74 | ||

| 22 July 2010 | X | CIET meets with Senator Lucia Topolanski, President Mujica’s wife, to explain the risks of weakening the regulations. Mujica’s wife suggests speaking directly to the president and in response CIET requests a meeting with President Mujica.44 | ||

| 23 July 2010 | X | Health Ministry announces on the radio the government is going to eliminate Ordinance N. 514 and weaken Decree N. 287 by lowering the size of HWLs from 80 to 65%.68 | ||

| 24 July 2010 | X | Former President Vazquez criticises Mujica government for weakening the regulations.71 | ||

| 28 July 2010 | X | Health groups send letters to petition President Mujica to defend regulations and offer technical assistance.75 | ||

| 30 July 2010 | X | President Mujica announces on the radio that tobacco companies are powerful enemies but that Uruguay will continue to explore options in maintaining the regulations.73 | ||

| 3 August 2010 | X | Former President Vazquez meets with current President Mujica and urges him to accept the help from the international health groups and defend the regulations.73 | ||

| 5 August 2010 | X | Officials from the Mujica administration reach out to CIET and TFK inviting them to a meeting to discuss the international legal ramifications of the regulations.44,49 | ||

| 10 August 2010 | X | International delegation of lawyers meet with top government officials and communicate that Uruguay has a strong legal case to defend the regulations. TFK offers financial assistance to help defend the regulations against the PMI investment dispute challenge.76 | ||

| 27 August 2010 | X | TFK sends a letter to Uruguayan government to further communicate that there is widespread support from transnational tobacco control network and their commitment of financial support to minimise legal costs of a potential arbitration case against PMI.78 | ||

| 29 September 2010 | X | PAHO Executive Committee unanimously approves a resolution supporting Uruguay’s tobacco control program and critical of PMI arbitration challenge, the first official statement by an international body on the PMI vs. Uruguay dispute.79 | ||

| 30 September 2010 | X | TFK’s legal team meet again with top government officials to further communicate their commitments to generating international support.80 | ||

| 4 October 2010 | X | Uruguayan Foreign Minister Luis Almagro announces the governments’ intention to pursue the arbitration against PMI and accept financial support from the TFK.81 | ||

| 6 October 2010 | X | TFK sends a follow-up letter to top government officials to explain their plan to generate positive media coverage of the PMI vs Uruguay dispute in Uruguay and build public support for Uruguay’s position from other countries and international organisations.80 | ||

| 15–20 November 2010 | X | FCTC Secretariat holds fourth COP meeting in Punta del Este, Uruguay and issues the Punta del Este Declaration, which declares countries can prioritise public health regulations over trade agreements provided they are consistent with the WTO TRIPS agreement.25 | ||

| 16 November 2010 | X | WHO holds press conference to announce it will provide scientific evidence to support regulations and coordinate briefings related to trade and tobacco.44 | ||

| 16 November 2010 | X | Michael Bloomberg issues a press release and personally calls President Mujica to announce that he (through TFK) will help finance Uruguay’s legal defense against PMI.84 | ||

| 15 March 2011 | X | ICSID arbitration proceedings officially begin.85 | ||

| 23 September 2011 | X | X | Uruguayan government files a memorandum challenging ICSID jurisdiction claiming PMI was required under treaty to litigate treaty disputes in domestic courts first.85 | |

| 28 August 2012 | X | X | The Administrative Court rejects Abal’s challenge and upholds the Health Ministry’s jurisdiction and authority to implement Decree N. 287.62 | |

| 3 July 2013 | X | X | ICSID arbitrators denied Uruguay’s motion to dismiss PMI’s legal challenge.85 | |

| 28 January 2015 | X | WHO and FCTC secretariat submit amicus brief to support the Uruguayan regulations.86 | ||

| 6 March 2015 | X | PAHO submits an amicus brief to support the Uruguayan regulations.87 | ||

| 5 October 2015 | X | Uruguayan delegates participate in oral hearings on the merits of the case.85 | ||

| 8 July 2016 | X | ICSID rejects PMI’s investment dispute, ruling that PMI has to pay US$7 million of Uruguay’s cost and an additional US$1.5 million for administrative fees and expenses and confirms Uruguay’s sovereign right to implement the regulations.85 | ||

BIT, Bilateral Investment Treaty; CIET, Centro de Investigacion para la Epidemia del Tabaquismo (Tobacco Epidemic Research Center);COP,Conference of the Parties; FCTC; Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; ICSID: International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes; PAHO, Pan-American Health Organization; PMI, Philip Morris International; SUT, Sociedad Uruguaya de Tabacologia (Uruguayan Tobacco Society); TFK, Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids; TRIPS, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights; WTO, World Trade Organization.

Figure 1.

For example, cigarette package sold in Uruguay with single brand presentation and pictorial health warning labels (HWLs) covering 80% front and back of the package. Package reads: ‘Smoking causes bad breath, stained teeth and unpleasant odour’ (translated by author).

METHODS

Between August 2014 and June 2016, we reviewed Uruguayan tobacco control legislation (available at https://parlamento.gub.uy/), government and health group reports (https://www.google.com.uy) and newspaper articles (www.elpais.com.uy) using standard snowball searches34 beginning with search terms ‘advertencias sanitarias’, ‘el comercio internacional’, ‘tratado bilateral de inversion’, ‘propiedad intellectual’, ‘marcas’, ‘Philip Morris’ and ‘Abal Hermanos,’ as well as key dates and specific actors. Between November 2014 and July 2015, we attempted to recruit 26 interviewees via email and telephone and 16 agreed to be interviewed (four denied our requests and six never responded after multiple requests). The 16 interviewees included seven Uruguayan tobacco control advocates, three congressmen, five Ministry of Health officials and one Ministry of Foreign Relations official. The interviewees agreed to waive their anonymity in accordance with a protocol approved by the University of California, Santa Cruz Committee on Human Research. Results were triangulated and thematically analysed through standard process tracing frameworks.35

RESULTS

Abal (PMI) domestic and international legal threats

Between September 2008 and June 2009, Abal sent five letters to the Health Ministry (table 1) arguing the packaging and labelling regulations were unconstitutional, beyond the executive’s jurisdiction and violated Uruguay’s obligations under two treaties governing trademark and investment rights, the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property and the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).36–38 Abal argued the regulations violated a 1991 Uruguay-Switzerland bilateral investment treaty (BIT) and threatened to file a complaint with the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) seeking compensation for damages.

Vazquez administration’s response to Abal’s first threats (2008–2010)

Despite Abal’s threats, the administration remained firm on the regulations. The Health Ministry recognised trade and investment agreements presented new complexities beyond their expertise and requiring discussions with the Ministries of Economy and Foreign Affairs.39,40 Their support41 for the Health Ministry’s approach to HWLs was necessary since each ministry had different priorities and stakeholders. President Vazquez’s support,41 as well as public support for tobacco control and Uruguay’s international commitments to the FCTC42 were vital to defending the regulations.

Health officials contacted local health groups, the Centro de Investigacion para la Epidemia del Tabaquismo (CIET, Tobacco Epidemic Research Centre) and the Sociedad Uruguaya de Tabacología (SUT, Uruguayan Tobacco Society) for information on the regulations’ international legal implications; these organisations asked the US-based Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (TFK, supported by the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use43 and the Framework Convention Alliance (FCA) for help.44–48

Political support in the legislature

In addition to support by the executive branch, there was strong support for the regulations in the Uruguayan congress. Legislators confirmed local tobacco control organisations, CIET and SUT, and President Vazquez changed the culture of tobacco control in Uruguay and achieved strong political consensus for the regulations49–51 assisted by strong public support,45–48,52,53 and a reduction in hospital admissions following Uruguay’s smokefree law.54 This assistance proved critical because unlike other countries,55–57 congress did not attempt to weaken the regulations.49–51

Abal’s domestic legal challenge

After failing to force the Vazquez administration to withdraw the regulations, between 2009 and 2012 Abal unsuccessfully filed two lawsuits58–60 to block the single pack presentation on the grounds that the Health Ministry did not have jurisdiction to issue the ordinance and that only congress could restrict Abal’s constitutional rights. Then Abal unsuccessfully sued to block the requirement for the 80% pictorial HWLs, again arguing the Health Ministry did not have authority to issue the decree61,62 (table 1).

PMI ratchets up threats against new Mujica administration (2010–2015)

On 1 March 2010, while the domestic legal challenges were pending and a week before new President Mujica took office, PMI filed a request for arbitration with ICSID under the Uruguay-Switzerland BIT.63 PMI argued the regulations expropriated PMI’s trademark property rights without compensation, the company was not provided fair and equitable treatment under a stable regulatory environment, and was not dealt with properly by Uruguayan courts (table 2). PMI sought damages which it later quantified as US$25.7 million, and requested the tribunal order Uruguay to suspend the regulations, an unusual request that was later dropped as investor-state disputes usually only award monetary damages.64 PMI’s statements concerning intellectual property and investment in trade agreements were magnified by front page stories in major Uruguayan newspapers.65,66 The ICSID’s Secretary General registered PMI’s challenge as within the jurisdiction of the Centre on 26 March 2010.67

Table 2.

Summary of Philip Morris International’s (PMI) investment dispute and International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes’s (ICSID) ruling85

| PMI’s claims | Tribunal ruling | Tribunal quotes |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Regulations expropriate PMI’s property rights without compensation | a.) Regulations did not substantially deprive PMI’s value of investment as a.) PMI could continue selling tobacco in Uruguay and b.) The state can exercise its right to regulate in the public good (police powers) c.) The registration of PMI’s trademarks does not grant them the right to use those trademarks |

‘As long as sufficient value remains after the Challenged Measures are implemented, there is no expropriation. As confirmed by investment treaty decisions, a partial loss of the profits that the investment would have yielded absent the measure does not confer an expropriatory character on the measure.’ (P 286) ‘Protecting public health has long since been recognised as an essential manifestation of the State’s police powers’ (P 291) ‘The Tribunal notes that there is nothing in the Paris Convention that states expressly that a mark gives a positive right to use’ (P 260) ‘nowhere does the TRIPS Agreement, assuming its applicability, provide for a right to use’ (P 262) ‘The Claimants (PMI) also argue that a trademark is a property right under Uruguayan law which thus accords a right to use. Again, nothing in their argument supports the conclusion that a trademark grants an inalienable right to use the mark.’ (P 266) ‘The Tribunal concludes that under Uruguayan law or international conventions to which Uruguay is a party the trademark holder does not enjoy an absolute right to use, free of regulation, but only an exclusive right to exclude third parties from the market so that only the trademark holder has the possibility to use the trademark in commerce, subject to the State’s regulatory power’ (P 271) |

|

| ||

| (2) Regulations are arbitrary and not supported by evidence so they do not accord PMI with fair and equitable treatment | Regulations were not arbitrary as they fulfilled Uruguay’s national and international legal obligations for protecting public health under the FCTC | ‘It should be stressed that the (Challenged Measures) have been adopted in fulfilment of Uruguay’s national and international legal obligations for the protection of public health’ (P 302) ‘For a country with limited technical and economic resources, such as Uruguay, adhesion to the FCTC … represented an important if not indispensable means for acquiring the scientific knowledge and market experience needed for the proper implementation of its obligations under the FCTC’ (P 393) ‘In these circumstances there was no requirement for Uruguay to perform additional studies or to gather further evidence in support of the Challenged Measures’ (P 396) |

|

| ||

| (3) Regulations do not meet PMI’s legitimate expectations of a stable regulatory environment | Given the harmful effects of tobacco, it would be reasonable to expect stronger regulation of tobacco over time | ‘In light of widely accepted articulations of international concern for the harmful effects of tobacco, the expectation could only have been of progressively more stringent regulation on the sale and use of tobacco products. Nor is it a valid objection to a regulation that it breaks new ground.’ (P 430) |

|

| ||

| (4) Uruguayan courts have not dealt properly with PMI’s domestic legal challenges and there was a denial of justice | The domestic rulings may appear unusual but investment tribunals should not act as courts of appeal to national courts to find a denial of justice | ‘In general, when considering procedural improprieties arbitral tribunals have adopted a high threshold for a denial of justice. For a denial of justice to exist under international law there must be ‘clear evidence of … an outrageous failure of the judicial system’ or a demonstration of ‘systemic injustice’ …’ (P 500) |

FCTC, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; PMI, Philip Morris International.

Mujica administration’s response to PMI’s second set of threats (2010–2015)

Mujica’s administration told the media that they were ‘reviewing’ the issue.65 Between April and June 2010, reports surfaced that PMI was privately negotiating an amendment to the regulations with the Ministers of Economy, Foreign Affairs and Health.44,49 While it is unclear what occurred during these private meetings, on 23 July 2010 Health Minister Daniel Olesker (2010–2015) announced the regulations would be amended by eliminating the single pack presentation rule and reducing the size of HWLs from 80% to 65%.68

Early mobilisation by local health groups in Uruguay

In February and March 2010, CIET and SUT published opinion-editorials in newspapers denouncing PMI’s attempt to intimidate the government.69,70 In March 2010, during a WHO meeting, CIET convened a meeting with TFK and FCA, Uruguayan government officials, and WHO lawyers to request support defending the regulations.44,49

After learning about the government’s private negotiations with PMI, CIET alerted the media and met with government officials to argue for maintaining the regulations.44,47 In June and July 2010, CIET continued publishing opinion-editorials and participated in media interviews highlighting the industry’s interference.53 In June, CIET wrote former President Vazquez stating changes to the regulations would reverse progress in Uruguay and set a bad precedent for the region.44 In July, CIET met with Senator Lucia Topolanski, President Mujica’s wife, to explain the risks of weakening the regulations. She told CIET to speak directly with the president. CIET requested a meeting and was eventually invited (together with a delegation of international lawyers) to discuss the regulations in August44,47–49,53 (table 1).

Response from former President Vazquez

On 24 July 2010, a day after Health Minister Olesker announced the government intended to weaken the regulations, the press and CIET contacted former President Vazquez who appeared on television to express disappointment in the Mujica administration and oppose weakening the regulations.71 Luis Almagro, Minister of Foreign Affairs, responded, telling reporters the government remained committed to fighting tobacco but was uncertain of the regulations’ legality under international trade law.72

A few days later, Mujica said in a radio interview that the government’s approach to the regulations had been ‘no simple thing’ and that his government faced ‘a clever and powerful enemy’ and was seeking other options to avoid contracting ‘lawyers at $1500 an hour for several years’.73

A week later, Mujica visited Vazquez to privately discuss PMI’s legal threats and the regulations, when Vazquez reportedly urged Mujica to defend the regulations and seek international support.73 Mujica reportedly acknowledged that Vazquez made some convincing arguments but that he was still concerned about the legal costs of fighting PMI, and was continuing to evaluate the situation.

International support to the Uruguayan government

CIET requested TFK’s assistance to help the government defend the regulations.44,49 In response, TFK wrote President Mujica on 16 July 2010, (a week before the public announcement of the weakened regulations) offering legal support and requesting that his administration not settle with PMI.74 On 28 July 2010, (four days after the public announcement of the weakened regulations), TFK coordinated a letter signed by several international health groups urging Mujica to defend the regulations.75 This support and Vazquez’s encouragement helped Mujica reconsider defending both regulations in August 2010.75

Bloomberg financial support

On 10 August 2010, the international delegation of lawyers met high level government officials and congressmen to argue against settling. They told the government that it had a strong legal case76 because international law, including the Uruguay-Switzerland BIT, recognised governments’ authority to protect public health. Uruguay’s legal position was strengthened by being a party to the FCTC, which recommends the implementation of strong regulations.77 With authorisation from the Bloomberg Foundation, TFK offered financial assistance to the Uruguayan government to help support Uruguay’s legal defence.

Generating international political support for Uruguay

In late August, TFK reiterated to the Uruguayan government the widespread global support to Uruguay’s case.78 In September 2010, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the WHO regional office for the Americas, became the first inter-governmental health organisation to formally support Uruguay.79 PAHO’s Executive Committee passed a resolution which specifically expressed support for Uruguay implementing FCTC recommended policies and urged member states to oppose tobacco industry interference.79 PAHO also offered technical support to the Health Ministry, focusing on the Conference of the Parties (COP), the FCTC’s governing body, scheduled to be held in Uruguay in November 2010.

In late September and early October, TFK reiterated its offer of financial and technical support to defend the regulations and develop a communications strategy80 (table 1). On 4 October 2010, the Foreign Minister held a press conference to announce the government would fight PMI and accept the financial support provided by Bloomberg though TFK.81 From this point on, the Mujica administration took a strong stance against PMI and the investment challenge to ensure the regulations would be protected.

The fourth COP meeting in Uruguay

The FCTC COP, which had been scheduled 2 years earlier, was held in Punta del Este, Uruguay in November 2010, providing further international support to Uruguay. During the COP, international health groups informed governments and generated international media coverage of PMI’s attempts to intimidate Uruguay82 (table 1). Uruguay produced and tabled the Punta del Este Declaration, supported by the FCTC Parties attending the COP (except the EU, China and Japan), declaring the rights of sovereign countries to prioritise public health regulations over trade agreements.25 The declaration specifically recognised the Parties’ concern regarding industry attempts to undermine government tobacco control regulations and Parties’ right and commitment to implement the FCTC.25 The EU successfully proposed adding the clause, ‘provided that such measures are consistent with the TRIPS agreement.’25

This international support sent a clear signal that Uruguay was not alone in defending its regulations against PMI. Former President Vazquez and President Mujica addressed the COP, acknowledging the assistance from the transnational tobacco control network and the courage required to defend the regulations.25,83 The WHO held a press conference and announced it would provide scientific evidence supporting the regulations and coordinate briefings related to trade and tobacco control to assist other governments in defending their regulations against legal challenges.44

On 15 November 2010, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced he had offered $500 000 to help defend Uruguay’s regulations against the investment challenge and personally called President Mujica to offer his support.84 This ongoing assistance included legal collaboration with the law firm retained by the Uruguayan government to represent it throughout the ICSID proceedings.

PMI investment challenge

After the ICSID Secretary General registered PMI’s investment dispute on 26 March 2010, the Uruguayan government and PMI spent a year selecting arbitrators for the tribunal, which was constituted in March 2011.85 In September 2011, Uruguay filed a memorandum arguing the tribunal did not have jurisdiction to hear the claim as PMI was required under the treaty to litigate in domestic courts before seeking arbitration,85 which the arbitrators denied in 2013.85 The next 2 years each party presented their arguments to the tribunal, which reviewed the case. In January and March 2015, the WHO and FCTC Secretariat86 and PAHO87 presented separate amicus briefs expanding on the scientific evidence and public health justification for the regulations. President Tabaré Vazquez, re-elected in 2014 and resuming office in March 2015, appointed a new team to coordinate the legal defence for the oral hearings on the merits of the case held in Washington, DC in October 2015.

In July 2016, ICSID rejected PMI’s claims and ruled Uruguay had the sovereign right to protect public health.88 ICSID ruled the regulations did not substantially deprive PMI’s value of investment, were not arbitrary, reasonable and expected regulations, and handled properly in Uruguayan domestic courts85 (table 2). The tribunal noted PMI’s total costs were US$16.9 million while Uruguay’s total costs were US$10.3 million and ruled PMI had to pay US$7 million of Uruguay’s cost and an additional US$1.5 million for ‘all of the fees and expenses of the Tribunal and ICSID’s administrative fees and expenses’,85 leaving the government to pay $3.3 million. Bloomberg through TFK funded $1.5 million of the $3.3 million legal defence.

DISCUSSION

The Uruguayan case illustrates how strong political support, an actively engaged local civil society, and international financial and technical support are important factors in overcoming tobacco industry legal threats to defend public health policies.89,90

Strong political support

The Vazquez and Mujica administrations demonstrated strong political commitments to tobacco control and ensuring the regulations were protected. President Vazquez’s leadership and prioritising tobacco control helped alter the culture of tobacco control in Uruguay, demonstrating the importance of political champions in advancing tobacco control measures. Uruguay’s Health Ministry established supportive communication with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, illustrating the importance of developing interagency alliances and a whole-of-government approach91 to implement the FCTC and resolve differences at the intersection of health and trade.

Active engagement by local civil society

Similar to successful tobacco control advocacy efforts in other countries,17,57,92,93 local civil society groups developed close relationships with government officials, provided evidence-based information to policy-makers, and closely monitored swift government actions and industry activity to advance tobacco control in Uruguay. When the Mujica administration considered weakening the regulations to avoid an expensive legal battle with PMI (whose 2010 annual net revenues exceeded $64 billion versus Uruguay’s $32 billion GDP73 local health groups mobilised support from former President Vazquez and international health groups to produce a strong united response to support defending the regulations.

Support by the transnational tobacco control network

The united front between local and international health organisations demonstrates the value of the transnational tobacco control network in combating tobacco industry interference and supporting FCTC implementation,13,94,95 especially in low-income and middle-income countries.19,20,57 Even though international health organisations could have responded sooner to the government’s legal concerns, organisations such as TFK, WHO, and PAHO have become more knowledgeable about trade and investment issues. Advocacy networks and epistemic communities have continuously improved the links between science and advocacy to advance tobacco control policy13,14,94,96; the Uruguay case highlights how this network strengthened the links between trade and tobacco control to combat emerging pressures of trade on health. The network recognised the importance of legal precedents in tobacco control,97 contributing to their decision to support Uruguay’s regulations as a global tobacco control issue.

International financial and technical support

Bloomberg’s financial contributions highlight that trade and investment disputes create substantial burdens for small and financially vulnerable countries, which can be strong incentives for governments to settle these lawsuits. As a result, international organisations have focused more attention and resources towards this growing concern, especially in low and middle-income countries. In particular, in March 2015 Bloomberg and Bill Gates launched a $4 million ‘anti-tobacco trade litigation fund’ to assist countries in drafting legislation ‘to avoid legal challenges and potential trade disputes’, and if challenges arise to provide funds for actual litigation defence expenses.98

Domestic and international legal implications

PMI’s losses to Uruguay in domestic and international courts are the latest in a string of losses at the national and international level. Constitutional courts upheld strong tobacco control policies in fourteen countries.17,19,93,99 In particular, the Australian,100 UK101 and Indian102 High Courts upheld strong packaging and labelling policies, concluding similarly to the 2016 ICSID Uruguay ruling, that the registration of tobacco company trademarks did not prevent governments from restricting their use and imposing such restrictions was not expropriating their intellectual property rights. The EU Court of Justice also upheld the EU Tobacco Products Directive103 that grants the authority for each EU member to implement plain packaging104 and an arbitration tribunal dismissed as an ‘abuse of rights’ a BIT investment challenge filed by PMI against Australia’s plain packaging law on jurisdictional grounds.105

PMI’s loss to Uruguay in ICSID, along with other defeats, provides greater legal clarity surrounding a country’s sovereign right to implement public health regulations. While there is no binding precedent in international arbitration law, the broader value of each award can contribute to the development and understanding of investment treaty law vis-a-vis tobacco control.106 By highlighting the importance of the FCTC in justifying evidence-based tobacco control measures, ICSID’s ruling should assist other countries, including New Zealand, Canada, Norway, South Africa, Malaysia, Turkey, India, Panama, Brazil, Ecuador and Chile, which, as of February 2017, were implementing or had announced plans to introduce similar tobacco packaging and labelling regulations.107,108

A more direct way to minimise the tobacco industry’s ability to threaten governments would be eliminating the application of ISDS mechanisms in relation to tobacco (and public health more broadly)4 in trade and investment agreements. Without the ISDS mechanism in the Uruguay-Switzerland BIT, PMI would have had to convince a WTO member to challenge Uruguay’s regulations. Forced to lobby WTO member states to file trade disputes can also backfire; after tobacco companies paid the fees for the Ukraine government to challenge Australia’s plain packaging policy, health advocates convinced the new government to withdraw the claim because Ukraine had no tobacco trade with Australia.109 Ten months after Australia announced the plain packaging proposal, PMI moved ownership of its Australian operations from Switzerland to Hong Kong to challenge Australia’s plain packaging policy under a 1993 Australia-Hong Kong BIT.110 This treaty shopping also failed when the investment dispute was rejected on jurisdictional grounds.111

LIMITATIONS

Top government officials in the president’s office and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs declined requests to be interviewed for this study, limiting the complete understanding of how the Mujica administration responded to tobacco industry legal threats. To protect attorney-client privileges policy-makers in the Health Ministry and Foreign Affairs Ministry could not discuss legal advice given to the President surrounding the PMI investment challenge against Uruguay.

CONCLUSION

To replicate Uruguay’s success, other countries need to recognise that strong political support, an actively engaged local civil society, and financial and technical support are important factors in overcoming tobacco industry legal threats to defend strong public health regulations. Uruguay’s historic legal victory should provide legal clarity for other countries interested in implementing similar tobacco packaging and labelling regulations.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject?

-

►

Tobacco companies have threatened governments over their packaging and labelling laws with international investment lawsuits since the 1980s.

What important gaps in knowledge exist on this topic?

-

►

Historically, some countries have dropped or delayed strong packaging and labelling rules in the face of legal threats from the industry but Uruguay, a small middle-income country, successfully resisted these threats with strong political leadership and support from the transnational tobacco control network.

What does this study add?

-

►

This is the first case study of how a tobacco company tried using investor protection provisions in an international trade and investment treaty in order to intimidate a government into withdrawing, weakening or delaying progressive tobacco packaging and labelling regulations. Uruguay illustrates how strong political will at the national level with support from the transnational tobacco control network helped a small and financially vulnerable country confront the tobacco industry in an international investment dispute to defend its public health regulations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Eckford, Eduardo Bianco and the interviewees for the information provided for this study.

Funding This work was supported by the Tobacco Related-Disease Research Program Dissertation Research Award 24DT-0003, the Horowitz Foundation for Social Policy Dissertation Research Grant, the National Cancer Institute Training Grant 2T32 CA113710-11 and research grant R01 CA-087472. The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

Contributor EC collected the raw data and prepared the first draft and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. PS and SAG helped revise the paper.

Competing interests PS is employed by the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. EC and SAG have nothing to declare.

Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the UCSC Committee on Human Research.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mamudu HM, Hammond R, Glantz SA. International trade versus public health during the FCTC negotiations, 1999–2003. Tob Control. 2011;20:e3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.035352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer ER, Brenner JE, Houston TP. International trade agreements: a threat to tobacco control policy. Tob Control. 2005;14(Suppl 2):ii, 19–25. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackey TK, Liang BA, Novotny TE. Evolution of tobacco labeling and packaging: international legal considerations and health governance. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e39–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosbie E, Gonzalez M, Glantz SA. Health preemption behind closed doors: trade agreements and fast-track authority. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e7–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKenzie R, Collin J. “Trade policy, not morals or health policy”: the US Trade Representative, tobacco companies and market liberalization in Thailand. Glob Soc Policy. 2012;12:149–72. doi: 10.1177/1468018112443686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarman H, Schmidt J, Rubin DB. When trade law meets public health evidence: the world trade organization and clove cigarettes. Tob Control. 2012;21:596–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrady B. In: Implications of ongoing trade and investment disputes concerning tobacco: philip morris v uruguay. Tania Voon AM, Liberman J, Ayres G, editors. Washington DC: Georgetown university; 2012. https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=096101005029120020085105099025003072014032009009067021125028075125026006118023107081056106037048008024003098092085092103094026103081013034035001005087106117001103031054006075074072069015114096027125008118024072088066122067107094100094024118113071066066&EXT=pdf (accessed 5 Nov 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tienhaara K. Regulatory chill and the threat of arbitration: A view from political science. In: Brown C, Miles K, editors. Evolution in investment treaty law and arbitration. Vol. 2011. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: pp. 606–28. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosbie E, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry argues domestic trademark laws and international treaties preclude cigarette health warning labels, despite consistent legal advice that the argument is invalid. Tob Control. 2014;23:e7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee A, Ekanayake EM. Global regime on tobacco control?: the role of transnational advocacy networks. 2013 http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/abstract?site=eds&scope=site&jrnl=1936203X&AN=101332223&h=s3ENW3hm17Ui1jcVEuT59JDabqcWgIlx1juesXjh6qF0QgNMh1UEuxGFZs2%2fuLi%2fDw7UU6CEktGnBp7UZ7nYEQ%3d%3d&crl=&resultLocal=ErrCrlNoResults&resultNs=Ehost&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d1936203X%26AN%3d101332223 (accessed 10 Sep 2015)

- 11.Lipschutz RD, Rowe JK. Globalization, governmentality and Global Politics: Regulation for the rest of us? London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas PM. Introduction: epistemic communities and International policy coordination. international organization Winter. 1992;46:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mamudu HM, Gonzalez M, Glantz S. The nature, scope, and development of the global tobacco control epistemic community. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:2044–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farquharson K. Influencing policy transnationally: pro-and Anti-Tobacco global advocacy networks. Aust J Public Adm. 2003;62:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42811/1/9241591013.pdf. (accessed 12 Nov 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, et al. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015 Mar 14;385:1029–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crosbie E, Sebrié EM, Glantz SA. Strong advocacy led to successful implementation of smokefree Mexico city. Tob Control. 2011;20:64–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. Costa Rica’s implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Overcoming decades of industry dominance. Salud Publica Mex. 2016;58:62–70. doi: 10.21149/spm.v58i1.7669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uang R, Crosbie E, Glantz S. Tobacco control law implementation in a middle income country: transnational tobacco control networks overcoming tobacco industry opposition in Colombia. Global Public Health. 2016 doi: 10.1080/17441692.2017.1357188. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Implementation of effective cigarette health warning labels among low and middle income countries: state capacity, path-dependency and tobacco industry activity. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:241–5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders-Jackson AN, Song AV, Hiilamo H, et al. Effect of the framework convention on tobacco control and voluntary industry health warning labels on passage of mandated cigarette warning labels from 1965 to 2012: transition probability and event history analyses. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2041–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uang R, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Accelerated adoption of Smoke-Free laws after ratification of the world health organization framework convention on tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:166–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiilamo H, Glantz S. FCTC followed by accelerated implementation of tobacco advertising bans. Tob Control. 2016:28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053007. tobaccocontrol-2016-053007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiilamo H, Crosbie E, Glantz SA. The evolution of health warning labels on cigarette packs: the role of precedents, and tobacco industry strategies to block diffusion. Tob Control. 2014;23:e2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell A, Wainwright M, Mamudu H. A chilling example? Uruguay, Philip Morris international, and WHO’s framework convention on tobacco control. Med Anthropol Q. 2015;29:256–77. doi: 10.1111/maq.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Decree N. 35. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ministry of Public Health. 2005 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Uruguay/Uruguay-DecreeNo.35_005-national.pdf. (accessed 10 Dec 2015)

- 27.Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Decree N. 171. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ministry of Public Health. 2005 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Uruguay/Uruguay-DecreeNo.171-005-national.pdf. (accessed 10 Dec 2015)

- 28.Connolly GN, Alpert HR. Has the tobacco industry evaded the FDA’s ban on ‘Light’ cigarette descriptors? Tob Control. 2014;23:140–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borland R, Fong GT, Yong HH, et al. What happened to smokers’ beliefs about light cigarettes when "light/mild" brand descriptors were banned in the UK? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey Tob Control. 2008;17:256–62. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.023812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yong HH, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Impact of the removal of misleading terms on cigarette pack on smokers’ beliefs about ‘light/mild’ cigarettes: cross-country comparisons. Addiction. 2011;106:2204–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Executive decree N. 287. Montevideo, Uruguay: Office of the President. 2009 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Uruguay/Uruguay-DecreeNo287_009-national.pdf (accessed 10 Dec 2015)

- 32.Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Public ordinance N. 514. Montevideo, Uruguay: Ministry of Public Health. 2008 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Uruguay/Uruguay-Ordinance514-national.pdf (accessed 10 Dec 2015)

- 33.Brown J, DeAtley T, Welding K, et al. Tobacco industry response to menthol cigarette bans in Alberta and nova Scotia, Canada. Tob Control. 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053099. tobaccocontrol-2016-053099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9:334–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King G, Keohane RO, Verba S. Designing social inquiry: scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermanos A. Letter from abal hermanos to ministry of public health concerning public ordinance N. 514. 2008 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf (accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 37.Hermanos A. Letter from abal hermanos to ministry of public health concerning public ordinance N. 514. 2009 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf (accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 38.Hermanos A. Letter from abal hermanos to ministry of public health concerning executive decree N. 287. 2009 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf (accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 39.Lorenzo Ana. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abascal Winston. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muñoz Maria Julia. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gianelli Carlos. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.bergBloom. Bloomberg initiative to reduce tobacco use grants program. :2009. http://tobaccocontrolgrants.org/ (accessed 5 Mar 2015)

- 44.Bianco Eduardo. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sica Amanda. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beatriz Goja. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pineiro Diego. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esteves Elba. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asqueta Miguel. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xavier Monica. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radío Daniel. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez Adriana. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 27, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paullier Juan Carlos. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Montevideo, Uruguay: Jul 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sebrié EM, Sandoya E, Bianco E, et al. Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction before and after implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free policy in Uruguay: experience through 2010. Tob Control. 2014;23:471–2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salgado L. Cambios a la ley del control del tabaco favorece: industrias tabacaleras sobre la salud de los hondurenos: Framework Convention Alliance. :2011. http://www.uypress.net/uc_13313_1.html.

- 56.Dunkley Willis. Committee softens tobacco regulations. The observer. 2013 http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/news/Committee-softens-tobacco-regulations_15271139 (accessed 12 May 2016)

- 57.Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. The importance of continued engagement during the implementation phase of tobacco control policies in a middle-income country: the case of costa rica. Tob Control. 2017;26:60–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hermanos A. Request for injunction to ordinance N. 514. Montevideo, Uruguay: Tribunal de lo Contencioso Administrativo; 2009. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf (accessed 30 July 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hermanos A. Request for annulment of article 3 of ordinance N. 514 before the TCA. Montevideo, Uruguay: Tribunal de lo Contencioso Administrativo; 2009. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf. (accessed 30 Jul 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tribunal de lo Contencioso Administrativo. TCA decision No. 509 on abal’s Request for Annulment of Article 3 of Ordinance N. 514. Montevideo, Uruguay: 2011. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_Philip%2520Morris%2520S%88rl%2520v%2520Uruguay.pdf. (accessed 30 Jul 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hermanos Abal. Request for Annulment of Decree 287 before the TCA. Montevideo, Uruguay: Tribunal de lo Contencioso Administrativo; 2009. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf. accessed 30 Jul 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tribunal de lo Contencioso Administrativo. TCA decision No. 512 on Abal’s Request for Annulment of Decree 287 Montevideo, Uruguay. 2012 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_Philip%2520Morris%2520S%88rl%2520v%2520Uruguay.pdf (accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 63.World Bank International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. Philip morris brands sàrl, philip morris products S.A. and abal hermanos S.A.v. oriental republic of Uruguay notice of intent. Washington D.C: United States: Switzerland-Uruguay Bilateral Investment Treaty; 2010. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf. (accessed 16 Nov 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller S, Hicks GN. Investor-State dispute settlement: a reality check: center for strategic & international studies. :2015. https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/150116_Miller_InvestorStateDispute_Web.pdf. (accessed 18 Mar 2016)

- 65.Tiscornia F. Tabacalera demanda a uruguay en el exterior. El Pais. 2010 http://historico.elpais.com.uy/10/02/27/pecono_473697.asp (accessed 28 Jul 2015)

- 66.Cotelo E. Philip Morris versus Uruguay: contacto con Roberto Porzecanski, corresponsal de en perspectiva en estados unidos. El Espectador. 2010 http://www.espectador.com/internacionales/176011/philip-morris-versus-uruguay (accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 67.World Bank International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. Philip morris brands sàrl, philip morris products S.A. and abal hermanos S.A.v. oriental republic of Uruguay no. ARB 10/7. Washington D.C: United States: Switzerland-Uruguay Bilateral Investment Treaty; 2011. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/litigation/2512/UY_PhilipMorrisSàrlvUruguay.pdf. (accessed 14 Nov 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 68.onAn. Cambios a política antitabaco en manos de mujica. El Pais. 2010 http://historico.elpais.com.uy/10/07/26/ultmo_504258.asp (accessed 28 Jul 2015)

- 69.Bianco E. En juicio el juicio de Philip Morris. Comunidad. 2010 Feb 28;21 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bianco E. El control del tabaco en juego. Comunidad. 2010 Feb 28;21 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Castillo F. Vázquez habló y el gobierno rebobinó. El Pais. 2010 http://historico.elpais.com.uy/10/07/27/pnacio_504417.asp (Accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 72.Carroll R. Uruguay bows to pressure over anti-smoking law amendments: tobacco giant philip morris accused of corporate bullying following government’s decision to water down legislation. The Guardian. 2010 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jul/27/uruguay-tobacco-smoking-philip-morris (accessed 18 Oct 2015)

- 73.Paolillo C. Part III: Uruguay vs. Philip Morris: Tobacco giant wages legal fight over South America’s toughest smoking controls. The center for public integrity. 2010 https://www.publicintegrity.org/2010/11/15/4036/part-iii-uruguay-vs-philip-morris. (accessed 12 Aug 2015)

- 74.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Letter from TFK and international health groups to president Mujica regarding support for Uruguay against Philip Morris international. 2010 Jul 16; [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alliance FC. Victory! Uruguay keeps warning labels. :2010. http://www.fctc.org/fca-news/packaging-and-labelling/395-victory-uruguay-keeps-warning-labels (accessed 12 Aug 2015)

- 76.Cotelo E. ONGs anti-tabaco: la posición uruguaya en el litigio contra philip morris es muy fuerte. El Espectador. 2010 http://www.espectador.com/politica/191038/ongs-anti-tabaco-la-posicion-uruguaya-en-el-litigio-contra-philip-morris-es-muy-fuerte (accessed 22 Aug 2015)

- 77.World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of article 11 of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control (Packaging and labeling of tobacco products) 2008 http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_11.pdf (accessed 10 Apr 2012)

- 78.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Letter from TFK to diego canepa regarding support for Uruguay against Philip Morris international. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pan American Health Organization. Resolution CD50.R6: strengthening the capacity of member states to implement the provisions and guidelines of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. 2010 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/166856/1/CD50.R6-e.pdf (accessed 20 Oct 2016)

- 80.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Follow up letter from TFK to Diego Canepa regarding support for Uruguay against Philip Morris International. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smink V. Uruguay se prepara su batalla contra philip morris. BBC Mundo. 2010 http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2010/10/101006_uruguay_batalla_tabacalera_cigarros_philip_morris_jrg.shtml (accessed 30 Jul 2015)

- 82.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Fourth session of the conference of the parties to the WHO FCTC. Punta Del Este; Uruguay: 2010. http://www.who.int/fctc/cop/sessions/fourth_session_cop/en/ (accessed 10 Jul 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garces R. World health organization takes on tobacco lobby. Bloomberg. 2010 http://www.businessweek.com/ap/financialnews/D9JGR7300.htm (accessed 29 Jul 2015)

- 84.Wilson D. Bloomberg backs Uruguay’s Anti Smoking Laws. New York Times. 2010 http://prescriptions.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/15/bloomberg-backs-uruguays-anti-smoking-laws/?_r=0 (accessed 21 Apr 2016)

- 85.International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. Philip morris brands sarl, philip morris products S.A. and abal hermanos S.A. and oriental republic of uruguay ICSID case no. ARB/10/7 award. Washington D.C: United States; 2016. http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw7417.pdf (accessed 10 Jul 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 86.World Health Organization. Written submission (Amicus curiae brief): Philip Morris brands sarl v. oriental republic of Uruguay. Washington D.C: United States: International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes; 2015. http://www.who.int/fctc/Amicus-curiae-brief-WHO-WHOFCTC.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed 18 Nov 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pan American Health Organization. Written submission (Amicus curiae brief): Philip Morris brands sarl v. oriental republic of Uruguay. Washington D.C: United States: International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes; 2015. file:/// Users/ericcrosbie/Downloads/Uruguay-amicus-6-March-15-FINAL.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 88.Castaldi M, Esposito A. Philip Morris loses tough-on-tobacco lawsuit in Uruguay. Reuters. 2016 http://www.reuters.com/article/us-pmi-uruguay-lawsuit-idUSKCN0ZO2LZ (accessed 10 Jul 2016)

- 89.Nixon ML, Mahmoud L, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry litigation to deter local public health ordinances: the industry usually loses in court. Tob Control. 2004;13:65–73. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ibrahim JK, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry litigation strategies to oppose tobacco control media campaigns. Tob Control. 2006;15:50–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lencucha R, Drope J, Chavez JJ. Whole-of-government approaches to NCDs: the case of the Philippines interagency Committee-Tobacco. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:844–52. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Charoenca N, Mock J, Kungskulniti N, et al. Success counteracting tobacco company interference in Thailand: an example of FCTC implementation for low- and middle-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:1111–34. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9041111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sebrié EM, Schoj V, Travers MJ, et al. Smokefree policies in Latin America and the caribbean: making progress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:1954–70. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gneiting U. From global agenda-setting to domestic implementation: successes and challenges of the global health network on tobacco control. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(Suppl 1):i74–86. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Collin J. Tobacco control, global health policy and development: towards policy coherence in global governance. Tob Control. 2012;21:274–80. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Champagne BM, Sebrié E, Schoj V. The role of organized civil society in tobacco control in Latin America and the caribbean. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S330–9. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Local nordic tobacco interests collaborated with multinational companies to maintain a united front and undermine tobacco control policies. Tob Control. 2013;22:e2–164. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.McKay B. Bloomberg, gates launch antitabaco fund. WSJ. 2015;18 http://www.wsj.com/articles/bloomberg-gates-launch-antitobacco-fund-1426703947. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Crosbie E, Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry success in Costa Rica: the importance of FCTC article 5.3. salud publica de mexico. 2012 Jan;54:28–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.High Court of Australia. Japan international SA and british american tobacco australiasia v. the commonwealth of Australia. Canberra, Australia: 2011. http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/litigation/decisions/au-20121005-jt-intl.-and-bat-australasia-l (accessed 25 May 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 101.High Court of the United Kingdom. British american tobacco, Philip Morris, japan international SA, and imperial tobacco v. the commonwealth of Australia. London, England: 2016. https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/judgments/british-american-tobacco-others-v-department-of-health/ (accessed 25 May 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rana P. Inda’s Supreme Court Orders Tobacco Companies to Comply With Health Warning Rules. WSJ. 2016;4 Available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/indias-supreme-court-orders-tobacco-companies-to-comply-with-health-warning-rules-1462366934. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jolly D. European court of justice upholds strict rules on tobacco. New York Times. 2016 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/05/business/eus-highest-court-upholds-strict-smoking-rules.html (accessed 25 May 2016)

- 104.European Parliament, Council of Ministers. Directive 2014/40/EU on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the member states concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products repealing directive 2001/37/EC. Brussels, Belgium: 2014. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/tobacco/docs/dir_201440_en.pdf (accessed 21 Oct 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 105.United Nations Commission on International Trade Law. Philip Morris international limited v. commonwealth of Australia (Procedural order No. 8.Geneva, Switzerland: 1993 Australia-Hong bilateral investment treaty. 2014 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/litigation/decisions/au-20140414-philip-morris-asia-limited-v (accessed 12 Jul 2016)

- 106.Commission J. Precedent in investment treaty arbitration: a citation analysis of a developing jurisprudence. J Int’l Arb. 2007;24:129–58. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin MM. Health ministry hits pause on plain tobacco packaging plan. Malay Mail Online. 2016 http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/health-ministry-hits-pause-on-plain-tobacco-packaging-plan (accessed 25 May 2016)

- 108.Kozak R. Cigarette maker to cut operations as congress debates tobacco law. WSJ. 2015;9 Available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/cigarette-maker-to-cut-chile-operations-as-congress-debates-tobacco-law-1436475357. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miles T. Ukraine drops WTO action against australian tobacco-packaging laws. Reuters. 2015 http://www.reuters.com/article/wto-tobacco-idUSL5N0YP3S420150603 (accessed 25 May 2016)

- 110.United Nations Commission on International Trade Law. Philip Morris international limited v. commonwealth of Australia (Procedural order no. 4) Geneva, Switzerland: 1993. Australia-Hong Bilateral Investment Treaty, 2012 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/litigation/decisions/au-20121130-philip-morris-asia-limited-v.-. (accessed 12 Jul 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 111.Taylor R. Philip Morris loses latest case against Australia Cigarette-Pack laws. WSJ. 2015;18 http://www.wsj.com/articles/philip-morris-loses-latest-case-against-australia-cigarette-pack-laws-1450415295. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Law 18.256. Montevideo, Uruguay: Senate and House of Representatives. 2008 http://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/Uruguay/Uruguay-LawNo.18.256-national.pdf. (accessed 10 Dec 2015)