Abstract

Background

A major SLE susceptibility locus lies within a common inversion polymorphism region (encompassing 3.8–4.5 Mb) located at 8p23. Initially implicated genes included FAM167A-BLK and XKR6, of which BLK received major attention due to its known role in B-cell biology. Recently, additional SLE risk carried in non-inverted background was also reported.

Objective & Methods

In this case-control study, we further investigated the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus (∼4 Mb) where we observed multiple SLE signals and assessed these signals for their relation to the inversion affecting this region. The study involved a North American discovery dataset (∼1,200 subjects) and a replication dataset (>10,000 subjects) comprising European-descent individuals.

Results

Meta-analysis of 8p23 SNPs, with P<0.05 in both datasets, identified 51 genome-wide significant SNPs (P<5.0×10-8). While most of these SNPs were related to previously implicated signals (XKR6-FAM167A-BLK subregion), our results also revealed 2 ‘new’ SLE signals, including SGK223-CLDN23-MFHAS1 (6.06×10-9≤meta P≤4.88×10-8) and CTSB (meta P=4.87×10-8) subregions that are located >2 Mb upstream and ∼0.3 Mb downstream from previously reported signals. Functional assessment of relevant SNPs indicated putative cis-effects on the expression of various genes at 8p23. Additional analyses in discovery sample, where the inversion genotypes were inferred, replicated the association of non-inverted status with SLE risk and suggested that a number of SLE risk alleles are predominantly carried in non-inverted background.

Conclusions

Our results implicate multiple (known+novel) SLE signals/genes at the extended 8p23 locus, beyond previously reported signals/genes, and suggest that this broad locus contributes to SLE risk through the effects of multiple genes/pathways.

Keywords: Lupus, SLE, 8p23, BLK, inversion

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease that is highly heterogeneous in clinical presentation and also highly variable in prognosis. As a complex human disease predominantly affecting women of reproductive age, SLE susceptibility and manifestation are modulated by a complex interplay of heritable, hormonal, and environmental factors. The complex genetic basis of SLE has been supported by a growing number of susceptibility loci/genes identified to date by candidate gene and/or genome-wide association (GWA) studies in various ethnic groups [1-3].

One of the major loci identified by initial high-density GWA studies (GWASs) of SLE in European-descent subjects [4-6] lies within a common large inversion polymorphism region (encompassing 3.8–4.5 Mb) on chromosome 8p23 [7-9] and has since been replicated in multiple studies and in various ethnic groups [1-3]. Initially implicated genes at 8p23 included FAM167A-BLK and XKR6, of which BLK (BLK proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/640) has subsequently received major attention due to its known role in B-lymphocyte development and signaling. BLK was also shown to physically interact with BANK1, another SLE-associated gene product involved in B-cell biology [10]. Following its first recognition for its involvement in SLE susceptibility, the 8p23 locus has also been shown to be associated with other autoimmune diseases [11-15].

The objective of our study was to further investigate the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus (∼4 Mb) where we observed multiple SLE signals and assess these signals for their relation to the inversion affecting this chromosomal region. The study involved a North American discovery dataset (∼1,200 subjects) and an independent replication dataset (>10,000 subjects) comprising European-descent subjects. Here we report our results that implicate multiple (known+novel) genes/signals in this broad 8p23 region, which seems to contribute to SLE risk beyond the commonly studied BLK gene.

Materials and Methods

Discovery dataset used for the investigation of the extended 8p23 locus

The chromosome 8p23 data were derived from a recent SLE GWAS conducted on Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0, that included 1,166 European-descent subjects after excluding those with cryptic relationship from ∼1,200 individuals initially genotyped [16]. SLE patients (n=676) were 18 years or older (mean ± SD age: 45.1 ± 12.5 years; 97.3% women) and all met 1982 or revised 1997 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for SLE [17, 18]. The controls (n=490) were 21 years or older (mean ± SD age: 48.9 ± 10.6 years; 100% women). Additional information on these samples can be found in previous publications [19-22]. At recruitment, written informed consents were obtained from all study subjects for the genetic studies approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating centers.

After applying the traditional GWAS quality control (QC) filters on samples/markers and also performing population stratification analysis, the final association analysis comprised 1,148 subjects (661 SLE cases and 487 controls) and included 1687 markers (MAF≥0.01, call rate ≥95%, HWE P>1.0×10-6) located at the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus (∼4 Mb). Logistic regression analysis was performed under an additive model using the recruitment site, sex, age, and first 4 principal components (PCs) as covariates. PLINK was used for all single-site association analyses (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/∼purcell/plink/), while Haploview v.4.2 was used for pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD), Tagger, and haplotype analyses (https://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/haploview).

Replication dataset used for the investigation of the extended 8p23 locus

Data from another recent and independent European GWAS of SLE [23] were used for the replication of SLE signals observed at the extended 8p23 locus in the discovery sample. The replication sample included 4,036 SLE patients (90% women) and 6,959 controls (50% women; 5,699 from the NIH Health and Retirement Study) genotyped on HumanOmni1-Quad BeadChip. The data were imputed to the density of the 1000 Genomes Project study (using the 1000 genomes phase 1 reference panel and IMPUTE V2.2.3) and the association analysis [24] was performed under an additive model computed by SNPTEST using the first 4 PCs as covariates.

Meta-analysis of the discovery and replication datasets for relevant markers

The METAL software [25] was used to perform the meta-analysis of discovery and replication datasets for the markers that showed P<0.05 in both datasets.

In silico assessment of putative functional effects of the top SLE-associated variants

RegulomeDB v1.1 (http://www.regulomedb.org/), a database of DNA features and regulatory elements in non-coding genomic regions in humans, was used to evaluate the regulatory potential of the variants of interest. The details of RegulomeDB variant scoring scheme are provided in the Table S3 footnotes, which overall includes the following main categories: category 1 (indicates strongest functional evidence such as “alteration of transcription factor binding and a gene regulatory effect”) for “likely to affect binding and linked to expression of a gene target”, category 2 for “likely to affect binding ”, category 3 for “less likely to affect binding”, and categories 4 to 6 for “minimal binding evidence”.

Additionally, the cis eQTL effects of the relevant SNPs were examined using an SQL database of genome-wide SNP associations with human monocyte expression traits [26]. This database was created from the data on 1,490 individuals of European origin obtained by using Affymetrix SNP Array 6.0 and Illumina Human HT12 BeadChip [26].

Assessment of chromosome 8 inversion status and its relation to the top SLE signals at 8p23

Given that the SLE locus at 8p23 falls within a known common inversion polymorphism (8p23-inv) region and a recent study [27] reported a new association between SLE and 8p23 non-inversion status, we also sought to infer the inversion genotypes in our discovery sample in order to assess the effect of inversion status on SLE susceptibility and its relation with SLE-associated SNPs. For this purpose, we adopted the same approach used by that recent SLE study [27] in order to obtain comparable results in our study. Given the lack of perfect surrogate marker(s) for 8p23-inv (due to the absence of markers in complete LD), this approach involves a novel statistical method that is based on a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) performed locally in the inversion region using unphased high-density SNP genotype data [28]. In our post-QC GWAS data (1,148 individuals), a total of 1687 SNPs (MAF≥0.01, spread over a ∼4 Mb region from position ∼8.1 Mb to ∼12.2 Mb on chromosome 8) were located in the predicted 8p23-inv region (spanning from 7.2 Mb to 12.4 Mb) of which 1489 were used to successfully merge our data with the HapMap-3 data (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/hapmap/genotypes/hapmap3_r3/plink_format/) from 267 Caucasian individuals [165 CEU and 102 TSI subjects, including some previously typed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay] [9, 27]. To infer the inversion status, PCs were calculated and the first PC was used to cluster the samples into three groups using the k-means algorithm and squared Euclidean distance as the similarity metric. Association analysis with the inversion status was performed using the same genetic model and covariates mentioned above for SNP association analysis performed in the discovery sample. The PLINK and R statistical software were used to conduct all necessary analyses.

Results

Investigation of known and new SLE association signals at the extended 8p23 locus

The 8p23 locus was among the top three known SLE loci replicated in our discovery sample following the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) locus at 6p21 and STAT4 at 2q32 [16]. At the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus (∼4 Mb), over 500 SNPs were observed at P<0.05 in our discovery sample, of which over 80 had P<0.001.

A total of 425 SNPs with P<0.05 in the discovery sample were also present and significant in the replication sample. Meta-analysis of these 425 markers identified a total of 51 SNPs with genome-wide significance (meta P<5.0×10-8) as the top SLE-associated variants (Table 1, Figure 1: red dots represent the SNPs with meta P<5×10-8). Figure S1 shows the LD and pairwise correlations among these 51 SNPs in the discovery sample. Tagger analysis of these 51 SNPs using an r2 cutoff of 0.5 (to identify the SNP groups that were not in high LD) yielded a total of 8 separate groups (Table 1). While most of these SNPs/groups were related to previously implicated SLE signals in the XKR6-FAM167A-BLK subregion (groups 2 through 7; 1.35×10-19≤meta P≤4.53×10-8), we also identified two ‘new’ SLE signals located upstream (>2 Mb) and downstream (∼0.3 Mb) from previously reported signals (Table 1, Figure 1: new SLE signals/subregions are marked by green arrows). The upstream ‘new’ SLE signal (group 1; 7 SNPs, 6.06×10-9≤meta P≤4.88×10-8) was identified in the SGK223-CLDN23-MFHAS1 subregion and the downstream ‘new’ SLE signal (group 8; rs880632, meta P=4.87×10-8) was detected near the CTSB gene (located upstream from the Beta-Defensin genes).

Table 1. Chromosome 8p23.1 SNPs that were significant in both discovery and replication samples and reached genome-wide level of significance in the meta-analysis.

| SNP | Position in bp (hg19) | aTagger results (r2≥0.5) | bAllele | Discovery dataset 661 cases & 487 controls | Replication dataset 4,036 cases & 6,959 controls | Meta P | Location in/between Gene(s)e | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Case Freq | Ctrl Freq | OR | cP | Case Freq | Ctrl Freq | OR | cP | dSNP impute | ||||||

| rs10087493 | 8373557 | Group 1 | A | 0.521 | 0.426 | 1.504 | 4.09E-05 | 0.485 | 0.455 | 1.141 | 5.04E-06 | 1 | 2.12E-08 | 5′-flanking (SGK223/CLDN23) |

| rs7827182 | 8380471 | Group 1 | C | 0.439 | 0.528 | 0.697 | 2.35E-04 | 0.481 | 0.513 | 0.877 | 5.20E-06 | 1 | 4.58E-08 | 5′-flanking (SGK223/CLDN23) |

| rs7817376 | 8380530 | Group 1 | T | 0.439 | 0.527 | 0.699 | 2.63E-04 | 0.486 | 0.517 | 0.877 | 5.26E-06 | 1 | 4.88E-08 | 5′-flanking (SGK223/CLDN23) |

| rs2428 | 8641145 | Group 1 | C | 0.461 | 0.540 | 0.742 | 2.85E-03 | 0.489 | 0.523 | 0.872 | 1.72E-06 | 0 | 4.51E-08 | 3′-flanking (CLDN23/MFHAS1) |

| rs332039 | 8723651 | Group 1 | G | 0.488 | 0.413 | 1.335 | 4.98E-03 | 0.464 | 0.426 | 1.163 | 2.38E-07 | 1 | 7.57E-09 | intron (MFHAS1) |

| rs1567398 | 8726804 | Group 1 | A | 0.460 | 0.399 | 1.270 | 1.95E-02 | 0.462 | 0.423 | 1.170 | 8.50E-08 | 1 | 6.06E-09 | intron (MFHAS1) |

| rs907183 | 8729761 | Group 1 | C | 0.505 | 0.427 | 1.438 | 3.45E-04 | 0.486 | 0.454 | 1.145 | 2.59E-06 | 1 | 2.51E-08 | intron (MFHAS1) |

| rs6980856 | 10938260 | Group 2 | G | 0.529 | 0.439 | 1.415 | 3.60E-04 | 0.507 | 0.475 | 1.143 | 3.83E-06 | 1 | 3.94E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs10108618 | 10953092 | Group 2 | G | 0.461 | 0.553 | 0.679 | 8.58E-05 | 0.476 | 0.507 | 0.873 | 2.73E-06 | 1 | 1.44E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs4841498 | 10985432 | Group 2 | C | 0.526 | 0.449 | 1.328 | 3.80E-03 | 0.519 | 0.480 | 1.173 | 2.76E-08 | 1 | 6.57E-10 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs10503416 | 10987553 | Group 3 | C | 0.380 | 0.451 | 0.745 | 3.69E-03 | 0.399 | 0.435 | 0.867 | 7.86E-07 | 1 | 2.26E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs17782554 | 11022106 | Group 3 | G | 0.342 | 0.417 | 0.750 | 4.29E-03 | 0.342 | 0.383 | 0.854 | 1.62E-07 | 1 | 4.56E-09 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs17726209 | 11022185 | Group 3 | C | 0.342 | 0.419 | 0.739 | 2.85E-03 | 0.342 | 0.383 | 0.854 | 1.61E-07 | 1 | 3.60E-09 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs9329238 | 11033737 | Group 3 | T | 0.331 | 0.406 | 0.720 | 1.47E-03 | 0.334 | 0.370 | 0.864 | 1.29E-06 | 1 | 2.35E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs7813802 | 11033976 | Group 2 | T | 0.528 | 0.452 | 1.345 | 3.62E-03 | 0.511 | 0.477 | 1.154 | 6.96E-07 | 1 | 2.02E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs4451268 | 11034859 | Group 3 | G | 0.334 | 0.408 | 0.728 | 2.05E-03 | 0.334 | 0.370 | 0.865 | 1.58E-06 | 1 | 3.49E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs11777887 | 11036799 | Group 3 | C | 0.330 | 0.406 | 0.715 | 1.21E-03 | 0.334 | 0.369 | 0.866 | 1.85E-06 | 1 | 3.21E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs11250119 | 11037034 | Group 2 | T | 0.428 | 0.518 | 0.720 | 6.62E-04 | 0.429 | 0.466 | 0.870 | 1.42E-06 | 0 | 1.75E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs2409720 | 11037903 | Group 3 | C | 0.330 | 0.413 | 0.715 | 9.08E-04 | 0.334 | 0.370 | 0.866 | 1.85E-06 | 1 | 2.74E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs7819412 | 11045161 | Group 2 | G | 0.525 | 0.442 | 1.393 | 7.40E-04 | 0.508 | 0.476 | 1.147 | 2.09E-06 | 1 | 2.84E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs11989369 | 11055385 | Group 3 | A | 0.326 | 0.404 | 0.716 | 1.23E-03 | 0.332 | 0.368 | 0.861 | 7.41E-07 | 1 | 1.18E-08 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs11783045 | 11056175 | Group 3 | G | 0.330 | 0.411 | 0.700 | 5.29E-04 | 0.332 | 0.369 | 0.861 | 6.60E-07 | 1 | 6.77E-09 | intron (XKR6) |

| rs7010590 | 11062882 | Group 2 | C | 0.464 | 0.544 | 0.721 | 8.55E-04 | 0.485 | 0.517 | 0.871 | 1.51E-06 | 1 | 2.12E-08 | 5′-flanking (XKR6/MTMR9) |

| rs4412337 | 11072020 | Group 3 | C | 0.325 | 0.407 | 0.706 | 6.75E-04 | 0.331 | 0.369 | 0.857 | 2.79E-07 | 1 | 2.97E-09 | 5′-flanking (XKR6/MTMR9) |

| rs2409745 | 11076635 | Group 2 | T | 0.518 | 0.435 | 1.423 | 3.75E-04 | 0.505 | 0.472 | 1.157 | 3.69E-07 | 0 | 3.05E-09 | 5′-flanking (XKR6/MTMR9) |

| rs2736313 | 11086942 | Group 2 | C | 0.463 | 0.536 | 0.740 | 1.89E-03 | 0.476 | 0.508 | 0.859 | 2.95E-07 | 1 | 5.43E-09 | 5′-flanking (XKR6/MTMR9) |

| rs920047 | 11087475 | Group 2 | T | 0.445 | 0.520 | 0.744 | 2.32E-03 | 0.468 | 0.502 | 0.859 | 3.58E-07 | 1 | 7.48E-09 | 5′-flanking (XKR6/MTMR9) |

| rs6601575 | 11097804 | Group 2 | C | 0.509 | 0.447 | 1.379 | 1.24E-03 | 0.483 | 0.450 | 1.146 | 2.40E-06 | 0 | 4.26E-08 | 5′-flanking (XKR6/MTMR9) |

| rs2249804 | 11215617 | Group 2 | C | 0.406 | 0.477 | 0.720 | 9.34E-04 | 0.441 | 0.472 | 0.871 | 1.77E-06 | 1 | 2.65E-08 | intron (TDH) |

| rs13260727 | 11232860 | Group 2 | A | 0.407 | 0.464 | 0.737 | 2.28E-03 | 0.433 | 0.465 | 0.859 | 1.56E-07 | 1 | 3.08E-09 | 3′-flanking (TDH/FAM167A) |

| rs2736292 | 11234500 | Group 2 | A | 0.411 | 0.472 | 0.735 | 1.93E-03 | 0.441 | 0.474 | 0.858 | 1.15E-07 | 1 | 2.00E-09 | 3′-flanking (TDH/FAM167A) |

| rs2736295 | 11234780 | Group 2 | C | 0.399 | 0.461 | 0.742 | 3.96E-03 | 0.432 | 0.465 | 0.860 | 1.77E-07 | 1 | 4.98E-09 | 3′-flanking (TDH/FAM167A) |

| rs2572449 | 11239137 | Group 2 | A | 0.396 | 0.457 | 0.739 | 2.46E-03 | 0.424 | 0.458 | 0.856 | 7.97E-08 | 1 | 1.55E-09 | 3′-flanking (TDH/FAM167A) |

| rs2736306 | 11239762 | Group 2 | A | 0.414 | 0.473 | 0.752 | 4.48E-03 | 0.439 | 0.472 | 0.858 | 1.15E-07 | 1 | 3.27E-09 | 3′-flanking (TDH/FAM167A) |

| rs2409756 | 11242025 | Group 2 | C | 0.390 | 0.454 | 0.740 | 2.79E-03 | 0.422 | 0.458 | 0.852 | 3.47E-08 | 1 | 6.96E-10 | 3′-flanking (TDH/FAM167A) |

| rs12680762 | 11332026 | Group 4 | A | 0.322 | 0.243 | 1.536 | 6.69E-05 | 0.299 | 0.262 | 1.259 | 4.68E-12 | 1 | 5.98E-15 | intron (FAM167A) |

| rs978803 | 11343475 | Group 5 | T | 0.524 | 0.455 | 1.316 | 4.09E-03 | 0.497 | 0.461 | 1.157 | 4.00E-07 | 1 | 1.16E-08 | 5′-flanking (FAM167A/BLK) |

| rs2736340 | 11343973 | Group 4 | T | 0.305 | 0.225 | 1.575 | 5.42E-05 | 0.303 | 0.254 | 1.302 | 2.14E-16 | 0 | 1.35E-19 | 5′-flanking (FAM167A/BLK) |

| rs2736342 | 11347289 | Group 5 | A | 0.511 | 0.442 | 1.280 | 1.07E-02 | 0.488 | 0.453 | 1.153 | 7.83E-07 | 1 | 4.14E-08 | 5′-flanking (FAM167A/BLK) |

| rs4840567 | 11347625 | Group 5 | A | 0.526 | 0.453 | 1.319 | 4.06E-03 | 0.497 | 0.461 | 1.155 | 5.61E-07 | 1 | 1.65E-08 | 5′-flanking (FAM167A/BLK) |

| rs2618476 | 11352541 | Group 4 | G | 0.328 | 0.237 | 1.625 | 2.39E-05 | 0.309 | 0.262 | 1.277 | 1.58E-14 | 0 | 8.08E-18 | intron (BLK) |

| rs998683 | 11353000 | Group 4 | A | 0.320 | 0.233 | 1.549 | 7.66E-05 | 0.309 | 0.262 | 1.278 | 1.26E-14 | 1 | 1.21E-17 | intron (BLK) |

| rs1478890 | 11355602 | Group 5 | C | 0.530 | 0.451 | 1.356 | 1.93E-03 | 0.502 | 0.469 | 1.148 | 2.05E-06 | 1 | 4.53E-08 | intron (BLK) |

| rs2618443 | 11384556 | Group 5 | A | 0.503 | 0.421 | 1.411 | 3.40E-04 | 0.479 | 0.448 | 1.144 | 2.80E-06 | 0 | 2.71E-08 | intron (BLK) |

| rs9329246 | 11392880 | Group 6 | G | 0.393 | 0.317 | 1.462 | 3.42E-04 | 0.368 | 0.335 | 1.162 | 5.42E-07 | 1 | 4.69E-09 | intron (BLK) |

| rs17153419 | 11394233 | Group 6 | C | 0.339 | 0.267 | 1.467 | 3.25E-04 | 0.325 | 0.290 | 1.191 | 2.19E-08 | 1 | 1.28E-10 | intron (BLK) |

| rs1478897 | 11395232 | Group 6 | T | 0.424 | 0.337 | 1.560 | 8.14E-06 | 0.403 | 0.367 | 1.168 | 1.58E-07 | 1 | 2.01E-10 | intron (BLK) |

| rs12677146 | 11450737 | Group 7 | C | 0.390 | 0.321 | 1.342 | 3.14E-03 | 0.373 | 0.344 | 1.159 | 9.91E-07 | 1 | 2.63E-08 | 3′-flanking (LINC00208), 5′-flanking (GATA4) |

| rs17807624 | 11463015 | Group 7 | A | 0.384 | 0.297 | 1.454 | 1.89E-04 | 0.360 | 0.329 | 1.156 | 1.46E-06 | 0 | 9.96E-09 | 3′-flanking (LINC00208), 5′-flanking (GATA4) |

| rs880632 | 11735939 | Group 8 | A | 0.222 | 0.287 | 0.694 | 1.39E-03 | 0.245 | 0.279 | 0.857 | 2.52E-06 | 0 | 4.87E-08 | 5′-flanking (CTSB), 3′-flanking (DEFB136) |

| rs11998678 | 11830150 | Group 2 | A | 0.535 | 0.445 | 1.522 | 5.31E-05 | 0.500 | 0.469 | 1.145 | 3.22E-06 | 1 | 1.44E-08 | 5′-flanking (CTSB), 3′-flanking (DEFB136) |

Tagger analysis results using an r2 cutoff of 0.5 in discovery sample data; Group 1/upstream new SLE signal (SGK223-CLDN23-MFHAS1 subregion), Groups 2-3 (XKR6-TDH subregion + DEFB subregion), Groups 4-7 (FAM167A-BLK subregion), Group 8/downstream new SLE signal (CTSB subregion).

Minor allele in discovery sample, Bold alleles: different strands were genotyped in discovery and replication samples.

P-value for additive genetic model, adjusted for relevant covariates (see the Methods section).

For the imputed SNPs (SNP impute=1) the imputation info score was >0.9 (see the Methods section).

Reviewed or validated genes.

Figure 1. Regional association plot on chromosome 8p23.

The associations observed in the discovery sample are depicted as diamonds while the results from the meta-analysis of discovery and replication samples are shown as dots (red dots: meta P<5×10-8, blue dots: 5×10-8<meta P<5×10-2). The genes located in the region (based on the UCSC genome browser) and the recombination rates by position (light blue line) are also shown. The SNP with strongest meta P is labeled and the new SLE signals/subregions identified in this study are marked by green arrows.

The LD between new and known SLE signals/SNPs was either minimal (0.07≤r2≤0.22 for the downstream ‘new’ signal) or weak to modest (0.18≤r2≤0.54 for the upstream ‘new’ signal) (Figure S1). One SNP (rs11998678) located further downstream at 8p23 (near Beta-Defensin genes) was in LD with other SNPs in group 2 (Table 1).

The pairwise conditional analysis results for top 51 SNPs in the discovery and replication samples are shown in Tables S1 & S2, respectively. As expected, the results of conditional analysis were influenced by the extent of pairwise correlations and the strength of individual associations. In the discovery sample, both of the top SNPs representing the upstream and downstream new SLE signals (rs10087493 and rs880632, respectively) were among the 4 SNPs that remained nominally significant (2.01×10-2≤ conditioned P≤4.19×10-2) after conditioning on the most significant BLK SNP (rs1478897) in this sample (see the related column in Table S1 - the last section/page of the table). Similarly in the replication sample, the rs880632 SNP that represents the downstream new SLE signal was the most significant SNP (conditioned P=1.61×10-2) after conditioning on the strongest BLK SNP (rs2736340) in this sample (see the related column in Table S2), followed by 4 SNPs with marginal P-values (4.72×10-2≤ conditioned P≤5.12×10-2) including the top SNP (rs1567398) representing the upstream new SLE signal in this sample. Overall, BLK/rs2736340 and CTSB/rs880632 were the only 2 SNPs that survived all pairwise conditional analyses in the large replication sample (see the related rows in Table S2).

In silico functional assessment of the top SLE signals identified at the extended 8p23 locus

Initial functional assessment of top 51 SNPs (with meta P<5.0×10-8) using RegulomeDB (Table S3-left panel) revealed the following: (i) a number of SNPs with strong regulatory potential (27 SNPs with the score of “1”), (ii) a consistent cis effect of most of the SNPs on the expression of CLDN23 and FAM167A (previously known as C8orf13) along with other regulatory functions, and (iii) the indication for cell type-specific effects/functions.

Subsequent evaluation of these 51 SNPs using the data from a recently published ‘monocyte’ eQTL study [26] (Table S3-right panel), which also used Affymetrix SNP Array 6.0 that was used in our discovery sample, further confirmed the consistent and most significant cis effect of all evaluated SNPs (including BLK SNPs) on the expression of CLDN23, a gene located within the ‘upstream new SLE signal’ subregion. Although at a lesser degree, a widespread cis effect of the evaluated SNPs was also observed on the expression of FAM167A (located near BLK), FDFT1 (located near CTSB), and SGK223 (located near CLDN23). On the other hand, the association with BLK expression was restricted to a subset of SNPs located within/near the previously implicated XKR6-FAM167A-BLK subregion (Table S3-right panel).

All 7 SNPs located within/near the SGK223-CLDN23-MFHAS1 subregion (upstream new SLE signal) showed cis effects on the expression of these 3 local genes and had RegulomeDB scores ranging from 1b to 6 (Table S3). Moreover, several other SNPs located throughout the extended 8p23 locus also showed association with the expression of SGK223 and CLDN23 in human monocytes (as stated above) and a few distant cis-eQTL effects were also observed on MFHAS1 (Table S3-right panel). While the rs880632 SNP (downstream new SLE signal - near CTSB; RegulomeDB score=1f) showed a cis effect on the expression of various genes (Table S3), it was the only SNP (out of 51) that was associated with CTSB expression.

Effect of the 8p23 inversion polymorphism on SLE susceptibility and its relation with the top SLE signals at 8p23

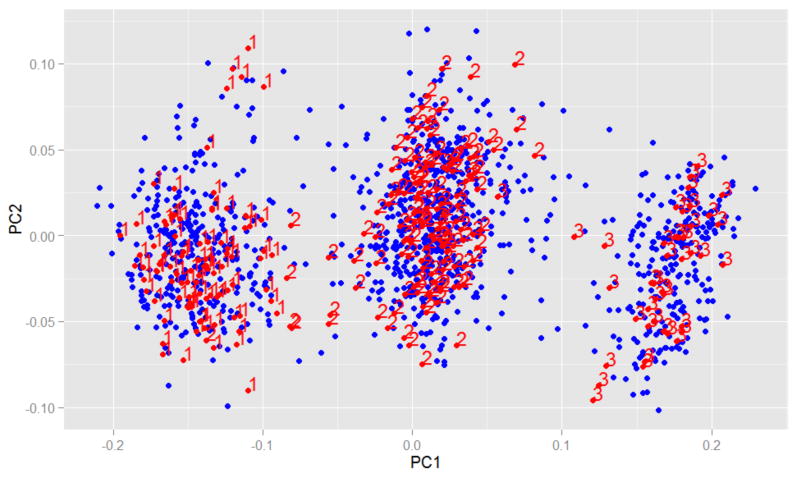

We used a recently developed PCA-based statistical approach [27, 28] to infer the inversion genotypes in our discovery sample in order to assess the effect of inversion status on SLE susceptibility and its relation to known and novel SLE signals at 8p23. Figure 2 shows three clusters identified by the PCA of our European-descent discovery sample (n=1,148, in blue) along with the HapMap-3 Caucasian sample (n=267, in red). The numbers indicate the inversion status; 1=Inverted homozygous, 2=Heterozygotes, 3=Non-inverted homozygous [27]. The distribution of 8p23-inv in our discovery sample was as follows: 28% inverted homozygous, 49% heterozygous and 22% non-inverted homozygous. The frequency of non-inversion allele was significantly higher in SLE cases than in controls (50.6% vs. 41.6%; OR=1.47, P=8.9×10-5) and the ratio of SLE cases to the controls in each group was as follows: 0.95 in inverted homozygous group, 1.44 in heterozygous group, and 1.94 in non-inverted homozygous group.

Figure 2. Principal component analysis (PCA) for inferring the inversion genotypes at 8p23.

Three inversion genotype clusters identified by the PCA of the European-descent discovery sample (n=1,148, blue dots) along with the HapMap-3 Caucasian sample (n=267, red dots/numbers) are shown. The numbers indicate the inversion status (1=Inverted homozygous, 2=Heterozygotes, 3=Non-inverted homozygous) previously inferred in HapMap subjects (see the Methods section for more information).

Figure S2 demonstrates the LD and pairwise correlations between the inversion polymorphism and 51 SLE-associated top SNPs in our discovery sample. 8p23-inv showed the lowest correlations with a subset of SNPs located within/near BLK gene (rs2736340, rs2618476, rs998683, rs9329246, rs1478897; 0.33≤r2≤0.39) and with the rs880632 SNP located near CTSB gene (downstream new SLE signal; r2=0.25).

In order to further assess the relation of 8p23-inv with 8 separate SNP groups described in the previous section (Table 1), we performed additional analyses on 8p23-inv and one SNP selected from each group (the most significant one in the discovery sample where the inversion genotypes were also available) along with additional BLK SNPs that showed strongest associations in the meta-analysis (meta P<5×10-15). Figure S3 shows the LD and pairwise correlations between the inversion polymorphism and 10 selected SNPs in our discovery sample (8 SNPs representing 8 separate groups + 2 additional BLK SNPs – italics: rs10087493-rs11783045- rs2736340-rs2618476-rs998683-rs2618443-rs1478897-rs17807624-rs880632-rs11998678). The LD findings (r2= 0.60 for inversion & rs10087493 and 0.25 for inversion & rs880632) and the haplotype analysis results (Table S4) have indicated that the upstream new SLE risk signal (represented by rs10087493 risk allele) is predominantly carried in the non-inverted background while the downstream new SLE risk signal (represented by rs880632 risk allele) is similarly observed in both non-inverted (N) and inverted (I) backgrounds. Haplotype association analysis of 8p23-inv + 10 selected SNPs (Table S4) has revealed that the most significant common haplotype carried all the risk alleles for SLE (NAATGAATACA; 18.9% in cases vs. 12.7% in controls, P=1.00×10-4) while the second most significant common haplotype carried all the protective alleles (IGGCAGGAGAG; 9.8% in cases vs. 14.5% in controls, P=8.00×10-4). The common haplotype that carried the risk allele of the downstream new SLE signal (represented by rs880632) but the protective alleles of all of the remaining SNPs was no longer significant (IGGCAGGAGCG; 12.5% in cases vs. 14.9% in controls, P=0.1086), neither was the 4th common haplotype that carried a combination of risk and protective alleles (IGACAGGAGCG; 6.0% in cases vs. 6.5% in controls, P=0.6659). The results of pairwise conditional analysis of 8p23-inv + 10 selected SNPs are shown in Table S5, where some SNPs maintained their significance after conditioning on 8p23-inv, which again seemed to be influenced by the extent of pairwise correlations and the strength of individual associations. All together, the above results have suggested that the (known+novel) signals that appear to contribute to SLE risk at the extended 8p23 locus appear to include a number of SNPs with risk alleles predominantly carried in non-inverted background as well as some SNPs acting more independent from the inversion.

Discussion

In this study, we further investigated the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus (∼4 Mb) where we identified multiple (known+novel) SLE signals (Figure 1, Table 1). We also assessed the functional significance of the identified SNPs/signals as well as their relation with the large inversion polymorphism (8p23-inv) affecting this chromosomal region [7-9].

Known and new SLE association signals at the extended 8p23 locus and their putative functional effects

Of a total of 425 SNPs that had P<0.05 in both discovery and replication samples at the extended 8p23 locus, 51 reached genome-wide level of significance (P<5.0×10-8) in meta-analysis (Table 1, Figure 1: red dots) and thus we focused on these top SLE-associated variants for further evaluation and analyses. These 51 SLE-relevant SNPs were divided into 8 separate groups after running a Tagger analysis in our discovery sample (Table 1). While most of these SNPs/groups were related to previously implicated SLE signals at 8p23 (the XKR6-FAM167A-BLK subregion), we also identified two ‘new’ SLE signals located upstream (>2 Mb) and downstream (∼0.3 Mb) from previously reported signals, falling within/near the SGK223-CLDN23-MFHAS1 and the CTSB subregions, respectively (Table 1, Figure 1: green arrows). The LD and pairwise correlations of these new SNPs/signals with the known SNPs/signals were either weak to modest (for upstream new SLE signal) or minimal (for downstream new SLE signal) (Figure S1). The newly identified SLE signals have also been further supported by the results of our conditional regression analyses (Tables S1 & S2).

Earlier studies on the effect of 8p23-inv on local gene expression have suggested that inversion-associated expression patterns and inversion-eQTLs are predominantly mediated by the effects of specific SNP/allele configurations maintained in the inversion background [8, 9]. Our in silico functional assessment of 51 SLE-relevant SNPs identified in the 8p23inv region using two public databases (Table S3) has revealed additional new and interesting findings. More than half of these SLE-relevant SNPs showed a RegulomeDB score of “1”, suggesting a strong regulatory potential. Moreover, a consistent and strong cis effect on CLDN23 expression in human monocytes was observed for these SLE-relevant SNPs (including the BLK SNPs) throughout the extended 8p23 locus, while the effect on BLK expression was restricted to a subset of SNPs located within/near the previously implicated XKR6-FAM167A-BLK subregion.

All 7 SNPs representing the upstream new SLE signal showed cis effects on the expression of 3 local genes (SGK223, CLDN23, and MFHAS1) residing in that 8p23 subregion (Table S3-right panel). CLDN23 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/137075) encodes a member of the claudin family of integral membrane proteins, which are structural and functional components of tight junctions that are involved in regulation of paracellular permeability and signal transductions in endothelia/epithelia [29]. Skin involvement constitutes a major component of SLE and epidermal tight junctions were proposed to be relevant for the pathogenesis of various inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions [30]. Consistent expression of tight junction proteins was also reported in human leukocytes, primarily in lymphocytes and monocytes, and they were suggested to play a role in immune activity and autoimmunity [31]. Tight junction proteins (e.g., CLDN19) were also proposed among possible biomarkers for refractory lupus nephritis [32]. SGK223 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/157285) encodes a member of the tyrosine protein kinase family and, in recent years, tyrosine kinases have been increasingly targeted for new drug development for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [33-35]. MFHAS1, a.k.a. MASL1 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/9258), encodes a ROCO protein that is believed to interact with the cell cycle and it was also shown to regulate the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-dependent signaling [36-38].

The rs880632 SNP that represents the downstream new SLE signal (near CTSB) showed a cis effect on the expression of the CTSB gene (Table S3-right panel) in addition to be associated with the expression of CLDN23, FAM167A (near BLK), and FDFT1 (near CTSB). CTSB (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/1508) encodes a lysosomal cysteine proteinase (cathepsin B) that plays various roles in protein turnover and cell processes and it has also been implicated in autoimmunity and arthritis [39-41]. Cathepsin B was shown to regulate various immune functions; e.g., persistence of memory T cells, antigen-presenting function of dendritic cells, monocyte and macrophage necrosis/necroptosis, and TLR signaling [42-46].

The publicly available data on human monocytes and lymphoblastoid cell lines (Table S3) have suggested cell type-specific effects/functions of the 8p23 SNPs as also supported by a recent BLK study [47]. Guthridge et al. [47] performed a comprehensive analysis of the FAM167A-BLK subregion, which has revealed two functional variants that regulate alternative promoter activities in cell-type- and developmental-stage- specific manners. Moreover, a recent SLE study [48] reported widely divergent transcriptional patterns in sorted immune cell populations, further emphasizing the importance of investigating multiple cell types in gene expression studies of SLE. Taking together the previous and current observations, the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus appears to contribute to SLE risk through multiple signals affecting the expression/function of various 8p23 genes in various cell populations in cell-type- and developmental-stage- specific manners and thus a comprehensive functional evaluation of this important broad SLE locus in various cell types is warranted.

The relation of the 8p23 inversion polymorphism with SLE and with top SLE signals at 8p23

Given that this extended 8p23 locus lies within a known inversion polymorphism (8p23-inv) region and a recent study [27] reported the association of non-inverted status as an additional risk factor for SLE, we also implemented the reported PCA-based approach to infer and assess the inversion genotypes in our discovery sample . The distribution of inversion genotypes in our sample and the ratio of SLE cases to controls in each genotype group were very similar to those reported previously [27], and the non-inversion allele was also found to be associated with increased SLE risk in our sample. Also consistent with the reported observation [27], the correlation of the inversion with some BLK SNPs was low in our sample (0.33≤r2≤0.39); however, it was the lowest with the newly identified CTSB signal/SNP (r2=0.25) and relatively higher with the newly identified SGK223-CLDN23-MFHAS1 signal/SNPs (0.54≤r2≤0.71) (Figure S2). Overall, the results from various analyses in our discovery sample (Figures S2-S3, Tables S4-S5) have suggested that multiple (known+novel) signals that appear to contribute to SLE risk at the extended 8p23 locus seem to be driven by multiple SNPs with risk alleles predominantly residing in non-inverted background as well as by some SNPs/alleles acting more independent from the inversion. Hence, the recently reported [27] additional SLE risk carried in non-inverted background may be related to some of the additional signals/SNPs identified in our study (Table 1). Given that inversions are known to influence the expression of multiple genes in affected regions [8, 9, 27], the SLE protective alleles carried in the inversion background might be executing their beneficial effects by altering the expression of multiple genes. However, for those SNPs that show high correlation with the inversion, it is statistically difficult to separate their individual effects from the inversion.

In conclusion, our results support the recent report of additional SLE risk carried in non-inverted background at 8p23 and furthermore implicate new SLE signals at the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus. Although the role of BLK in immune regulation is now well documented and that of newly implicated CTSB is also increasingly recognized, much remains to be learned about other newly implicated and relatively understudied SLE-relevant genes (SGK223, CLDN23, and MFHAS1) and their role in (or interactions with) the immune system. Overall, our results suggest that the extended 8p23 locus contributes to SLE risk through cell type-specific effects of multiple (known+novel) signals/genes involved in various (known+novel) biological pathways/mechanisms. Some of the newly implicated pathways/mechanisms include possible involvement of the paracellular transport pathway/tight junctions (CLDN23) and the protein turnover/cathepsins (CTSB). Our findings need to be further confirmed in independent large studies and also warrant a comprehensive analysis of this ‘extended’ 8p23 region beyond the frequently studied FAM167A-BLK subregion. Given that previous SLE studies on the FAM167A/BLK subregion [47, 49, 50] have identified both common and uncommon (low-frequency/rare) functional variants, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the ‘extended’ 8p23 locus harbors both common and uncommon SLE-relevant functional variants throughout the implicated region. Hence, a comprehensive follow-up analysis (sequencing + functional studies) of this important ‘broad’ locus at 8p23 is necessary to identify all common/uncommon causal variants, characterize their functions, and unravel the full spectrum of affected pathways/mechanisms, with the ultimate goal of improving our understanding of SLE pathogenesis and uncovering new targets for future therapeutic interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health [HL092397, HL088648, AR057028, AR046588, AR057338, HD066139, AR002138, AR030692, AR064464, and TR000150]; and by grants from Wellcome Trust (Ref 085492) and Arthritis Research UK (Ref 19289).

Footnotes

Contributors: FYD and MIK planned the study, conducted research, evaluated/interpreted the data/results, and drafted the manuscript. XW and EF conducted research, performed statistical analysis and/or provided statistical expertise and evaluated/interpreted the data/results. SB, CP, AC, RR-G, and SM conducted research, provided the samples/data and clinical expertise. DLM and TJV conducted research, performed the analyses in the replication sample and provided the replication data and expertise. All authors contributed to the research and to the critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Dai C, Deng Y, Quinlan A, Gaskin F, Tsao BP, Fu SM. Genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus: immune responses and end organ resistance to damage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;31:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerra SG, Vyse TJ, Cunninghame Graham DS. The genetics of lupus: a functional perspective. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(3):211. doi: 10.1186/ar3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaughn SE, Kottyan LC, Munroe ME, Harley JB. Genetic susceptibility to lupus: the biological basis of genetic risk found in B cell signaling pathways. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92(3):577–91. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, Lee AT, Chung SA, Ferreira RC, Pant PV, Ballinger DG, Kosoy R, Demirci FY, Kamboh MI, Kao AH, Tian C, Gunnarsson I, Bengtsson AA, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Petri M, Manzi S, Seldin MF, Ronnblom L, Syvanen AC, Criswell LA, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):900–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, Moser KL, Tsao BP, Vyse TJ, Langefeld CD, Nath SK, Guthridge JM, Cobb BL, Mirel DB, Marion MC, Williams AH, Divers J, Wang W, Frank SG, Namjou B, Gabriel SB, Lee AT, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW, Taylor KE, Fernando M, Zidovetzki R, Gaffney PM, Edberg JC, Rioux JD, Ojwang JO, James JA, Merrill JT, Gilkeson GS, Seldin MF, Yin H, Baechler EC, Li QZ, Wakeland EK, Bruner GR, Kaufman KM, Kelly JA. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):204–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Hackett R, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Parkin M, Gates C, Plenge RM, Behrens TW, Wither JE, Rioux JD, Fortin PR, Graham DC, Wong AK, Vyse TJ, Daly MJ, Altshuler D, Moser KL, Gaffney PM. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1059–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonacci F, Kidd JM, Marques-Bonet T, Ventura M, Siswara P, Jiang Z, Eichler EE. Characterization of six human disease-associated inversion polymorphisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(14):2555–66. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch N, Morell M, Ponsa I, Mercader JM, Armengol L, Estivill X. Nucleotide, cytogenetic and expression impact of the human chromosome 8p23.1 inversion polymorphism. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salm MP, Horswell SD, Hutchison CE, Speedy HE, Yang X, Liang L, Schadt EE, Cookson WO, Wierzbicki AS, Naoumova RP, Shoulders CC. The origin, global distribution, and functional impact of the human 8p23 inversion polymorphism. Genome Res. 2012;22(6):1144–53. doi: 10.1101/gr.126037.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillejo-Lopez C, Delgado-Vega AM, Wojcik J, Kozyrev SV, Thavathiru E, Wu YY, Sanchez E, Pollmann D, Lopez-Egido JR, Fineschi S, Dominguez N, Lu R, James JA, Merrill JT, Kelly JA, Kaufman KM, Moser KL, Gilkeson G, Frostegard J, Pons-Estel BA, D'Alfonso S, Witte T, Callejas JL, Harley JB, Gaffney PM, Martin J, Guthridge JM, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. Genetic and physical interaction of the B-cell systemic lupus erythematosus-associated genes BANK1 and BLK. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):136–42. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gourh P, Agarwal SK, Martin E, Divecha D, Rueda B, Bunting H, Assassi S, Paz G, Shete S, McNearney T, Draeger H, Reveille JD, Radstake TR, Simeon CP, Rodriguez L, Vicente E, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Mayes MD, Tan FK, Martin J, Arnett FC. Association of the C8orf13-BLK region with systemic sclerosis in North-American and European populations. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(2):155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lessard CJ, Li H, Adrianto I, Ice JA, Rasmussen A, Grundahl KM, Kelly JA, Dozmorov MG, Miceli-Richard C, Bowman S, Lester S, Eriksson P, Eloranta ML, Brun JG, Goransson LG, Harboe E, Guthridge JM, Kaufman KM, Kvarnstrom M, Jazebi H, Cunninghame Graham DS, Grandits ME, Nazmul-Hossain AN, Patel K, Adler AJ, Maier-Moore JS, Farris AD, Brennan MT, Lessard JA, Chodosh J, Gopalakrishnan R, Hefner KS, Houston GD, Huang AJ, Hughes PJ, Lewis DM, Radfar L, Rohrer MD, Stone DU, Wren JD, Vyse TJ, Gaffney PM, James JA, Omdal R, Wahren-Herlenius M, Illei GG, Witte T, Jonsson R, Rischmueller M, Ronnblom L, Nordmark G, Ng WF, Mariette X, Anaya JM, Rhodus NL, Segal BM, Scofield RH, Montgomery CG, Harley JB, Sivils KL. Variants at multiple loci implicated in both innate and adaptive immune responses are associated with Sjogren's syndrome. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1284–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orozco G, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Morgan AW, Wilson AG, Wordsworth P, Steer S, Hocking L, Thomson W, Worthington J, Barton A. Study of the common genetic background for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):463–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller FW, Cooper RG, Vencovsky J, Rider LG, Danko K, Wedderburn LR, Lundberg IE, Pachman LM, Reed AM, Ytterberg SR, Padyukov L, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Radstake TR, Isenberg DA, Chinoy H, Ollier WE, O'Hanlon TP, Peng B, Lee A, Lamb JA, Chen W, Amos CI, Gregersen PK. Genome-wide association study of dermatomyositis reveals genetic overlap with other autoimmune disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(12):3239–47. doi: 10.1002/art.38137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Li X, Wang G, Li X. Association of FAM167A-BLK rs2736340 Polymorphism with Susceptibility to Autoimmune Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. Immunol Invest. 2016;45(4):336–48. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2016.1157812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demirci FY, Wang X, Kelly JA, Morris D, Barmada MM, Feingold E, Kao AH, Sivils KL, Bernatsky S, Pineau C, Clarke A, Ramsey-Goldman R, Vyse TJ, Gaffney PM, Manzi S, Kamboh MI. Identification of a New Susceptibility Locus for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus on Chromosome 12 in Individuals of European Ancestry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):174–83. doi: 10.1002/art.39403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(11):1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernatsky S, Ramsey-Goldman R, Labrecque J, Joseph L, Boivin JF, Petri M, Zoma A, Manzi S, Urowitz MB, Gladman D, Fortin PR, Ginzler E, Yelin E, Bae SC, Wallace DJ, Edworthy S, Jacobsen S, Gordon C, Dooley MA, Peschken CA, Hanly JG, Alarcon GS, Nived O, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Isenberg D, Rahman A, Witte T, Aranow C, Kamen DL, Steinsson K, Askanase A, Barr S, Criswell LA, Sturfelt G, Patel NM, Senecal JL, Zummer M, Pope JE, Ensworth S, El-Gabalawy H, McCarthy T, Dreyer L, Sibley J, St Pierre Y, Clarke AE. Cancer risk in systemic lupus: an updated international multi-centre cohort study. J Autoimmun. 2013;42:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demirci FY, Dressen AS, Kammerer CM, Barmada MM, Kao AH, Ramsey-Goldman R, Manzi S, Kamboh MI. Functional polymorphisms of the coagulation factor II gene (F2) and susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(4):652–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pineau CA, Bernatsky S, Abrahamowicz M, Neville C, Karp I, Clarke AE. A comparison of damage accrual across different calendar periods in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2006;15(9):590–4. doi: 10.1177/0961203306071874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhew EY, Manzi SM, Dyer AR, Kao AH, Danchenko N, Barinas-Mitchell E, Sutton-Tyrrell K, McPherson DD, Pearce W, Edmundowicz D, Kondos GT, Ramsey-Goldman R. Differences in subclinical cardiovascular disease between African American and Caucasian women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Transl Res. 2009;153(2):51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bentham J, Morris DL, Cunninghame Graham DS, Pinder CL, Tombleson P, Behrens TW, Martín J, Fairfax BP, Knight JC, Chen L, Replogle J, Syvänen AC, Rönnblom L, Graham RR, Wither JE, Rioux JD, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Vyse TJ. Aberrant gene regulation in innate and adaptive immunity implicated by genetics in SLE pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2015;47(12):1457–64. doi: 10.1038/ng.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotival M, Zeller T, Wild PS, Maouche S, Szymczak S, Schillert A, Castagne R, Deiseroth A, Proust C, Brocheton J, Godefroy T, Perret C, Germain M, Eleftheriadis M, Sinning CR, Schnabel RB, Lubos E, Lackner KJ, Rossmann H, Munzel T, Rendon A, Erdmann J, Deloukas P, Hengstenberg C, Diemert P, Montalescot G, Ouwehand WH, Samani NJ, Schunkert H, Tregouet DA, Ziegler A, Goodall AH, Cambien F, Tiret L, Blankenberg S. Integrating genome-wide genetic variations and monocyte expression data reveals trans-regulated gene modules in humans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(12):e1002367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namjou B, Ni Y, Harley IT, Chepelev I, Cobb B, Kottyan LC, Gaffney PM, Guthridge JM, Kaufman K, Harley JB. The effect of inversion at 8p23 on BLK association with lupus in Caucasian population. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma J, Amos CI. Investigation of inversion polymorphisms in the human genome using principal components analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lal-Nag M, Morin PJ. The claudins. Genome Biol. 2009;10(8):235. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-8-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandner JM, Zorn-Kruppa M, Yoshida T, Moll I, Beck LA, De Benedetto A. Epidermal tight junctions in health and disease. Tissue Barriers. 2015;3(1-2):e974451. doi: 10.4161/21688370.2014.974451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandel I, Paperna T, Glass-Marmor L, Volkowich A, Badarny S, Schwartz I, Vardi P, Koren I, Miller A. Tight junction proteins expression and modulation in immune cells and multiple sclerosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(4):765–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjachat T, Tongyoo P, Tantivitayakul P, Somparn P, Hirankarn N, Prom-On S, Pisitkun P, Leelahavanichkul A, Avihingsanon Y, Townamchai N. Biomarkers for Refractory Lupus Nephritis: A Microarray Study of Kidney Tissue. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(6):14276–90. doi: 10.3390/ijms160614276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gadina M. Advances in kinase inhibition: treating rheumatic diseases and beyond. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(2):237–43. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson H, Nibbs R, McInnes I, Siebert S. Protein kinase inhibitors in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/cei.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robak T, Robak E. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors as potential drugs for B-cell lymphoid malignancies and autoimmune disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21(7):921–47. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.685650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dihanich S. MASL1: a neglected ROCO protein. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40(5):1090–4. doi: 10.1042/BST20120127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng AC, Eisenberg JM, Heath RJ, Huett A, Robinson CM, Nau GJ, Xavier RJ. Human leucine-rich repeat proteins: a genome-wide bioinformatic categorization and functional analysis in innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4631–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000093107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong J, Shi QQ, Zhu MM, Shen J, Wang HH, Ma D, Miao CH. MFHAS1 Is Associated with Sepsis and Stimulates TLR2/NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway Following Negative Regulation. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong B, Wan B, Wei Z, Wang T, Zhao P, Dou Y, Lv Z, Xia Y, Dai Y. Role of cathepsin B in regulating migration and invasion of fibroblast-like synoviocytes into inflamed tissue from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177(3):586–97. doi: 10.1111/cei.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toomey CB, Cauvi DM, Hamel JC, Ramirez AE, Pollard KM. Cathepsin B regulates the appearance and severity of mercury-induced inflammation and autoimmunity. Toxicol Sci. 2014;142(2):339–49. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan S, Sloane BF. Molecular regulation of human cathepsin B: implication in pathologies. Biol Chem. 2003;384(6):845–54. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byrne SM, Aucher A, Alyahya S, Elder M, Olson ST, Davis DM, Ashton-Rickardt PG. Cathepsin B controls the persistence of memory CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2012;189(3):1133–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo X, Dhodapkar KM. Central and overlapping role of Cathepsin B and inflammasome adaptor ASC in antigen presenting function of human dendritic cells. Hum Immunol. 2012;73(9):871–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garcia-Cattaneo A, Gobert FX, Muller M, Toscano F, Flores M, Lescure A, Del Nery E, Benaroch P. Cleavage of Toll-like receptor 3 by cathepsins B and H is essential for signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(23):9053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115091109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McComb S, Shutinoski B, Thurston S, Cessford E, Kumar K, Sad S. Cathepsins limit macrophage necroptosis through cleavage of Rip1 kinase. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):5671–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dabritz J, Weinhage T, Varga G, Wirth T, Ehrchen JM, Barczyk-Kahlert K, Roth J, Schwarz T, Foell D. Activation-dependent cell death of human monocytes is a novel mechanism of fine-tuning inflammation and autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1002/eji.201545802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guthridge JM, Lu R, Sun H, Sun C, Wiley GB, Dominguez N, Macwana SR, Lessard CJ, Kim-Howard X, Cobb BL, Kaufman KM, Kelly JA, Langefeld CD, Adler AJ, Harley IT, Merrill JT, Gilkeson GS, Kamen DL, Niewold TB, Brown EE, Edberg JC, Petri MA, Ramsey-Goldman R, Reveille JD, Vila LM, Kimberly RP, Freedman BI, Stevens AM, Boackle SA, Criswell LA, Vyse TJ, Behrens TW, Jacob CO, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Sivils KL, Choi J, Joo YB, Bang SY, Lee HS, Bae SC, Shen N, Qian X, Tsao BP, Scofield RH, Harley JB, Webb CF, Wakeland EK, James JA, Nath SK, Graham RR, Gaffney PM. Two functional lupus-associated BLK promoter variants control cell-type- and developmental-stage-specific transcription. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(4):586–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma S, Jin Z, Rosenzweig E, Rao S, Ko K, Niewold TB. Widely divergent transcriptional patterns between SLE patients of different ancestral backgrounds in sorted immune cell populations. J Autoimmun. 2015;60:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delgado-Vega AM, Dozmorov MG, Quiros MB, Wu YY, Martinez-Garcia B, Kozyrev SV, Frostegard J, Truedsson L, de Ramon E, Gonzalez-Escribano MF, Ortego-Centeno N, Pons-Estel BA, D'Alfonso S, Sebastiani GD, Witte T, Lauwerys BR, Endreffy E, Kovacs L, Vasconcelos C, da Silva BM, Wren JD, Martin J, Castillejo-Lopez C, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. Fine mapping and conditional analysis identify a new mutation in the autoimmunity susceptibility gene BLK that leads to reduced half-life of the BLK protein. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1219–26. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diaz-Barreiro A, Bernal-Quiros M, Georg I, Maranon C, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Castillejo-Lopez C. The SLE variant Ala71Thr of BLK severely decreases protein abundance and binding to BANK1 through impairment of the SH3 domain function. Genes Immun. 2016;17(2):128–38. doi: 10.1038/gene.2016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.