Abstract

Objective

Experience of stressful life events is associated with risk of depression. Yet many exposed individuals do not become depressed. A controversial hypothesis is that genetic factors influence vulnerability to depression following stress. This hypothesis is often tested with a “diathesis-stress” model, in which genes confer excess vulnerability. We tested an alternative formulation of this model: genes may buffer against depressogenic effects of life stress.

Method

We measured the hypothesized genetic buffer using a polygenic score derived from a published genome-wide association study (GWAS) of subjective wellbeing. We tested if married older adults who had higher polygenic scores were less vulnerable to depressive symptoms following the death of their spouse as compared to age-peers who had also lost their spouse and who had lower polygenic scores. We analyzed data from N=8,588 non-Hispanic white adults in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a population-representative longitudinal study of older adults in the United States.

Results

HRS adults with higher wellbeing polygenic scores experienced fewer depressive symptoms during follow-up. Those who survived death of their spouses (n=1,647) experienced a sharp increase in depressive symptoms following the death and returned toward baseline over the following two years. Having a higher polygenic score buffered against increased depressive symptoms following a spouse’s death.

Conclusions

Effects were small and clinical relevance is uncertain, although polygenic score analyses may provide clues to behavioral pathways that can serve as therapeutic targets. Future studies of gene-environment interplay in depression may benefit from focus on genetics discovered for putative protective factors.

Keywords: Stressful life events, depression, polygenic score, genome-wide association study, diathesis-stress

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a leading cause of disability burden globally (1). Depression is a particular concern among older adults, who are a growing population segment, and in whom depression may contribute to mobility limitation leading to disability and premature mortality (2). Depression in older adults shares etiological features with depression in younger adults, reflecting a combination of genetic and environmental influences (3). A critical question is why events that can trigger depressive episodes may impact some individuals differently than others.

Experience of stressful life events is associated with risk of depression (4; 5). Yet not all stress-exposed individuals become depressed. A controversial hypothesis is that genetic differences between individuals modify the influence of life-stress on depression (6). This “diathesis-stress” hypothesis is supported by family-based genetic studies that find individuals with familial liability to depression are more vulnerable to developing depression following stress exposure (7). Molecular genetic evidence for the diathesis-stress hypothesis from candidate-gene studies is contested, partly because of concerns about the candidate-gene approach (8). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) offer opportunities to move beyond arguments about candidate genes. GWAS discoveries for depression have yielded mixed results in tests of diathesis-stress models (9–11). A recent genome-wide association study of subjective wellbeing (12) offers the opportunity to evaluate the opposite end of the continuum of genetic liability.

Subjective wellbeing represents a dimension of so-called “positive psychology,” and may reflect the opposite end of an affective continuum from depression (13). Like depression, subjective wellbeing is heritable, with a portion of this heritability reflecting genetic influences shared with depression (14). Theory predicts increased subjective wellbeing should buffer against deleterious consequences of stressful life events (15).

We conducted a polygenic score study to test if genetic predisposition to greater subjective wellbeing buffered against risk of depression following experience of a stressful life event, the death of one’s spouse. We studied depressive symptoms in a cohort of older adults and their spouses followed longitudinally as part of the US Health and Retirement Study. We combined whole-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data already generated for the cohort and results from GWAS of subjective wellbeing in over 100,000 adults by the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (12) to calculate cohort members’ subjective wellbeing polygenic scores. Analysis tested if higher subjective-wellbeing polygenic score buffered survivors’ risk of developing depressive symptoms following the death of their spouse. For comparative purposes, we repeated analysis using polygenic scores based on GWAS of depression by the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (12) and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (16).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is a longitudinal survey of a representative sample of Americans aged 50+ and their spouses initiated in 1992 (17). HRS is administered biennially and includes over 26,000 persons in 17,000 households. Respondents are interviewed about economic, social, and health issues (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php).

Genetic Data

We linked HRS survey data compiled by Rand Corporation (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/rand/randhrsn/randhrsN.pdf) with genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data downloaded from US National Institutes of Health Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP, see supplementary information for details). Quality control procedures excluded SNPs missing in >5% of samples, with minor allele frequency <1%, or not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p<0.001). The final genetic database included approximately 1.7M SNPs.

Population stratification (the non-random patterning of allele frequencies across populations with different ancestries) may limit generalizability of polygenic scores derived in one population to others (18). To increase comparability of the analysis sample to the population studied in the original GWAS, we focused analysis on HRS respondents identified as non-Hispanic white based on analysis of genome-wide SNP data by the HRS investigators (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/genetics/HRS_QC_REPORT_MAR2012.pdf). The resulting analysis sample included N=8,588 individuals (58% female) born between 1905–1974 with average age 59 (IQR=53–66) years at first interview and participating in median 8 (IQR 6–10) follow-up assessments. The analysis dataset comprised a total of 67,805 observations. We also conducted our analysis using the sample of HRS respondents who self-identified as non-Hispanic white. Those results are reported in the supplementary information.

Wellbeing Polygenic Score

We calculated HRS respondents’ wellbeing polygenic scores from result of the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (SSGAC) GWAS of subjective wellbeing (12). That GWAS analyzed measures of life satisfaction, positive affect, and a combination of these scales defined as subjective wellbeing. The original GWAS included HRS respondents. To calculate polygenic scores for HRS respondents for this analysis, the SSGAC provided revised GWAS weights estimated from data excluding the HRS (restricted GWAS N=195,024). Therefore, there was no overlap between the samples used to develop the polygenic score and the sample we analyzed. Polygenic scoring was conducted according to the methods described by Dudbridge (19) following the protocol used in previous work (20). Briefly, we matched SNPs in the HRS genotype database with wellbeing GWAS SNPs. For each SNP, counts of wellbeing-associated alleles were weighted by GWAS-estimated effect-sizes. Weighted counts were summed across SNPs to compute polygenic scores. Polygenic scores were composed from all SNPs matched between the original GWAS and the HRS genotyped-SNP database (n=773,672 SNPs). We calculated polygenic scores based on all SNPs in the score for two reasons. First, this is the same method used by the SSGAC in their own polygenic score analysis (12). Second, theory, simulation evidence, and empirical evidence all agree that, for genetically complex traits, including all SNPs is the most reliable method to produce a polygenic score with maximum predictive power (19; 21; 22).

To account for residual population stratification in our non-Hispanic white sample, we computed residualized polygenic scores (20). We estimated principal components from the genome-wide SNP data for non-Hispanic white HRS respondents according to the method described by Price and colleagues (23) using the PLINK command pca. We then residualized the wellbeing polygenic score for the first 10 principal components, i.e. we regressed HRS respondents’ polygenic scores on the 10 principal-component scores and computed residual values from the predictions. Residualized polygenic scores were standardized to M=0, SD=1 for analysis.

Depression Polygenic Scores

We used the same methods to calculate two polygenic scores for depression from GWAS of clinical depression conducted by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium and GWAS of depressive symptoms by the SSGAC (12; 16). The SSGAC GWAS included the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium samples in addition to samples from UK Biobank and the Kaiser Permanente Genetic Epidemiology Research on Adult Health and Aging (GERA) databases.

Death of Spouse

Death of one’s spouse is a well-documented risk factor for developing depressive symptoms (24). During follow-up, n=1,647 (22% of those married) experienced the death of their spouse. These survivors (76% female, mean age 73 years) completed follow-up surveys on average 12 months after their spouse’s death (IQR=6–18 months, Supplemental Figure 1).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with the 8-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) scale at each HRS follow-up. The CESD is a valid psychometric instrument for assessment of depression in older adults (25). We analyzed the continuous CESD score. There was substantial within-person variability in depressive symptoms across follow-up (ICC=0.47, M=1.16, SD=1.74).

Analysis

We conducted descriptive analysis of HRS respondents’ depressive symptoms before and after the death of their spouses using non-parametric local regression. Local regression fits smoothed curves to data with nonlinear patterns by analyzing “localized” subsets of the data to build up a function iteratively (26). We used local regression to fit symptom data to time-from-death. The resulting model describes symptom levels leading up to and following spousal death. If the death of one’s spouse produces a change in depressive symptoms, this change will appear as a discontinuity in the local regression line estimated by the model, e.g. depressive symptom levels may “jump” from their trajectory before the death to a higher level after the death.

We conducted hypothesis tests using parametric nonlinear regression (27). Nonlinear regression models were estimated independent of the descriptive local regression analysis. Nonlinear regression estimates a function describing non-linear patterns in a set of data, and then models those nonlinearities as a function of other variables. Analysis modeled depressive symptoms at the first assessment following death of a spouse as a non-linear function of time since the death. We tested the hypothesis that wellbeing polygenic score would buffer against increase in depressive symptoms following death of a spouse using the coefficient for the association between polygenic score and that non-linear function.

Specifically, we estimated the model

in which α is the model intercept, χ is a vector of covariates, and εi is a normally distributed random error term. β1 estimates the main effect of the polygenic score on depressive symptoms. (β2+β3PGSi)exp[ti/(λ+γ PGSi)] estimates the dynamics of depression in the wake of spousal death. ti is time since the death, which is >0 for all observations. λ+γ PGSi estimates the decay rate for the shock caused by the death, specifically how the increase in depressive symptoms following death attenuates over time. The decay function has two components. λ is the population average decay function. γ describes how the decay function varies according to polygenic score. β2 estimates the main effect of spousal death. β3 tests the hypothesis that higher wellbeing polygenic score buffers against increases in depressive symptoms following spousal death. If β3<0, we reject the null hypothesis that polygenic score is unrelated to depressive symptoms following spousal death. Models covariates are birth year, age, and sex. A graphical representation of model components is shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

The nonlinear regression model focused on the first observations made of HRS respondents following the deaths of their spouses. Because HRS conducted follow-up assessments only every two years, repeated observations of individuals are unlikely to observe changes in depressive symptoms related to spousal death. Nevertheless, as a sensitivity analysis, we re-estimated the nonlinear regression model using all observations following spousal death, i.e. multiple observations per HRS respondent. Results are reported in Supplementary Figure 3.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the R software. We tested main-effect associations between HRS respondents’ polygenic scores and their depressive symptoms using random-intercept models implemented with the R package lme4. We fit local regression models to repeated measures depressive symptom data using the loess function and the nonlinear regression models using the nls function.

RESULTS

Higher wellbeing polygenic score was associated with reduced depressive symptoms

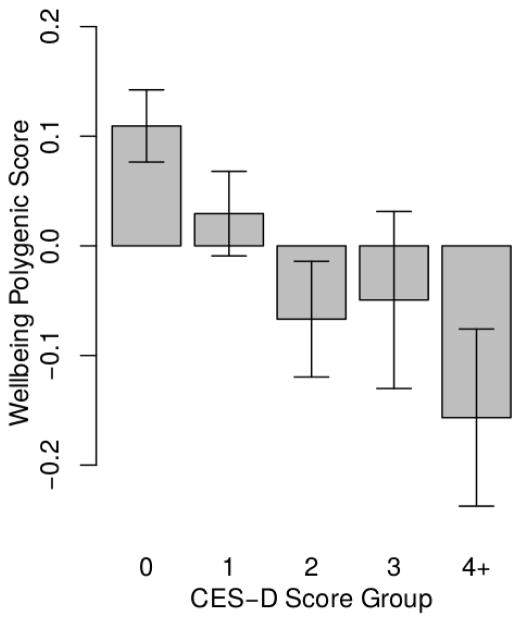

HRS respondents with higher polygenic scores experienced fewer depressive symptoms during follow-up (b=−0.10, CI=−0.13, −0.07, p<0.001; Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1 Model 1). This effect-size is consistent with previous analysis of the wellbeing polygenic score and depression (12). The genetic association with depressive symptoms was similar for men and women (p=0.803 for test of interaction between polygenic score and sex).

Figure 1. HRS respondents with higher polygenic scores reported fewer depressive symptoms during follow-up.

The figure shows average polygenic scores (denominated in standard deviation units) for groups of HRS respondents defined by their histories of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptom history was measured by averaging respondents’ CESD scores across repeated assessments. For graphing purposes, averaged scores were rounded to the nearest integer value. The resulting groups included 3,489 respondents with an average score of 0, 2,565 with a score of 1, 1,327 with a score of 2, 605 with a score of 3, and 602 with a score of 4 or higher.

Wellbeing polygenic score was not associated with likelihood of experiencing death of a spouse

Genetic liability to depression may influence exposure to stressful life events in older adults. Therefore, before testing the genetic buffering hypothesis, we evaluated possible gene-environment correlation between subjective wellbeing polygenic score and likelihood of experiencing spousal death. We found no evidence of such gene-environment correlation; HRS respondents’ polygenic scores were not related to their likelihood of experiencing the death of their spouse (OR=0.97, CI=0.92–1.02, p=0.219).

Death of a spouse was associated with an immediate increase in depressive symptoms, followed by a gradual return toward baseline over the following years

HRS respondents who experienced death of their spouse experienced a discontinuity in depressive symptoms around the time of the death. In local regression analysis, respondents’ depressive symptoms trended slightly upwards in the months immediately preceding the death, rose sharply at the time of death, and gradually returned toward baseline over the following two years (Figure 2). This pattern is consistent with previous reports on the course of depressive symptoms around spousal death (28).

Figure 2. Trajectories of depressive symptoms in the months surrounding the death of a spouse.

The figure shows local regression plots of depressive symptoms (CESD scores) by month of measurement relative to the death of a spouse. The plot reflects data from HRS respondents who experience spousal death (N=1,647; 14,309 total observations). Plotted points show mean x- and y- coordinates for bins of about 60 observations.

Nonlinear regression analysis estimated the increase in CESD associated with spousal death to be 1.97 points (95% CI 1.5–2.4, p=<0.001). This increase was smaller for respondents interviewed farther from the time of their spouse’s death. Based on trajectories estimated from the model, the increase in depressive symptoms that occurred following the death of a spouse attenuated by 12 months after the death, with modest further attenuation through 24 months (Supplemental Table 1 Model 2).

Genetics of subjective wellbeing buffered against increase in depressive symptoms following death of a spouse

HRS respondents with higher polygenic scores experienced flatter trajectories of depressive symptoms around the time of their spouse’s death as compared to peers who also lost their spouse and had lower polygenic scores. In local regression analysis, HRS respondents with higher wellbeing polygenic scores experienced fewer depressive symptoms in the months leading up to the death and a smaller increase in depressive symptoms following the death as compared to other survivors who had lower polygenic scores (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Trajectories of depressive symptoms for HRS respondents with low subjective wellbeing polygenic scores (red line) and high subjective wellbeing polygenic scores (blue line).

The figure shows local regression plots of depressive symptoms (CESD Scores) by month of measurement relative to the death of a spouse. Trajectories for respondents with low polygenic scores are graphed in red (1 or more SDs below the mean, n=255 individuals with 2,164 observations). Trajectories for HRS respondents with high polygenic scores are graphed in blue (1 or more SDs above the mean, n=242 individuals with 2,048 observations).

In nonlinear regression analysis, each standard-deviation increase in polygenic score buffered the increase in depressive symptoms following spousal death by 0.60 CESD points (95% CI 0.19, 1.02, p=0.004). In context, this effect estimate suggests a person with a polygenic score 1SD above the population mean should experience about half as much increase in depressive symptoms following death of their spouse as compared to a peer whose polygenic score was 1 SD below the population mean. Respondents’ polygenic scores were not related to the rate of attenuation in depressive symptoms following the death (γ=0.33, p=0.739, Supplemental Table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate consistency of findings. First, we repeated analysis including all HRS respondents who self-reported non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity (N=9,453; N=1,829 who survived the death of their spouse). Findings were similar to those in the analysis sample determined by genetically-defined ancestry (Supplemental Table 2).

Second, we repeated analysis using polygenic scores derived from two published GWAS of depression, the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium’s GWAS of major depressive disorder (16) and Social Science Genetic Association Consortium GWAS of depressive symptoms (12). We analyzed genetic overlap among phenotypes using LD-score regression (29) and polygenic score methods. LD-Score Regression estimates genetic correlations (rG) from GWAS summary statistics. We implemented LD Score regression using the LDSC Python software package (https://github.com/bulik/ldsc) following the method described by the SSGAC (12). Previous LD-Score regression analysis estimated rG between subjective wellbeing and depressive symptoms to be r=−0.80 (12). Genetic correlation computed from subjective wellbeing GWAS results excluding the HRS sample was similar (for depressive symptoms, rG=−0.81, SE=0.06; for major depressive disorder, rG=−0.78, SE=0.12). Empirical correlations between polygenic scores were lower (|r|=0.15–0.32). All genetic correlations and polygenic score correlations were statistically significant at the p<0.001 level.

Results from analysis of depression polygenic scores paralleled results from analysis of the subjective wellbeing polygenic score. HRS respondents with higher depression polygenic scores had higher levels of depressive symptoms across HRS follow-up. Among those who survived the death of their spouse, higher depression polygenic scores predicted a greater increase in depressive symptoms following the death (Figure 4). In nonlinear regression analysis, each standard-deviation increase in the Depressive Symptoms polygenic score amplified the increase in depressive symptoms following spousal death by 0.69 CESD points (95% CI 0.24, 1.14, p=0.003). The result was similar for the Major Depressive Disorder polygenic score (b=0.63 95% CI 0.21, 1.05, p=0.003). Results from analysis of depression polygenic scores are reported in Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 4. Trajectories of depressive symptoms for HRS respondents with high depression polygenic scores (red lines) and low depression polygenic scores (blue lines).

The figure shows local regression plots of depressive symptoms (CESD Scores) by month of measurement relative to the death of a spouse. Trajectories for respondents with high depression polygenic scores are graphed in red (1 or more SDs above the mean, n=224 individuals with 1,814 observations for the Major Depressive Disorder polygenic score, n=276 individuals with 2,350 observations for the Depressive Symptoms polygenic score). Trajectories for HRS respondents with low depression polygenic scores are graphed in blue (1 or more SDs below the mean, n=260 individuals with 2,165 observations for Major Depressive Disorder polygenic score, n=265 individuals with 2,217 observations for the Depressive Symptoms polygenic score).

DISCUSSION

We tested if genetics discovered in GWAS of subjective wellbeing buffered against development of depressive symptoms following death of a spouse. We analyzed data on depressive symptoms in 8,588 individuals followed longitudinally as part of the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS). During follow-up, 1,647 of these individuals experienced the death of their spouse. HRS respondents with higher polygenic scores experienced fewer depressive symptoms during follow-up. For those whose spouse died during the follow-up period, having higher polygenic score buffered against increased depressive symptoms following the death. Having a low polygenic score for depression had similar buffering effects on depression risk to having a high polygenic score for subjective wellbeing. Magnitudes of genetic effects were small.

This evidence of genetic buffering against depression following a stressful life event provides proof of concept for further investigation of the genetics of subjective wellbeing as a modifier of the life-stress to depression link. Studies of gene-environment interplay are controversial (30). Statistical and theoretical models are contested. The precise nature of any “interaction” between the stress of losing a spouse and wellbeing-related genetic background remains uncertain. What we find is that individuals who carry more wellbeing-associated alleles tend to develop fewer additional depressive symptoms following the death of their spouse. This “buffering” is independent of the “main effect” of genetics in the absence of a spousal death. Buffering is also not affected by any “gene-environment correlation” between genetics of subjective wellbeing and exposure to death of a spouse; HRS respondents’ subjective wellbeing polygenic scores were unrelated to their risk of losing their spouse during follow-up. Finally, we detected consistent evidence of buffering using two different statistical specifications, local regression and nonlinear regression, that take into account time elapsed between the stressful event and the measurement of depressive symptoms.

Findings have implications for relevance of wellbeing genetics in clinical approaches to bereavement and for research into gene-environment interplay. Clinically, genetic testing based on current knowledge is unlikely to be useful in planning for or managing bereavement. Effect sizes in our study were too small to be useful for predicting outcomes of individual patients. It is possible that larger-scale GWAS will furnish more predictive polygenic scores with greater clinical relevance. However, even with very-large GWAS, predictive power of polygenic scores for common, complex traits will be limited (31). Instead, our results may inform clinical research into candidate intervention targets to promote resilience in bereavement and in the context of other stressful experiences. Specifically, our findings raise questions about what behaviors or psychological processes mediate buffering effects. Do individuals with higher wellbeing polygenic scores process or cope with stress differently (32)? Do they cultivate different social support networks or interact with them in different ways? Studies to identify such mediators of genetic associations can inform interventions designed to promote resilience. Finally, given that we observed essentially the same result in analysis of polygenic scores for subjective wellbeing and depression, research is needed to evaluate if behavioral and psychological mediators of genetic influences measured by these scores are the same or different.

High genetic correlation between subjective wellbeing and depression (rG~0.8) suggests that polygenic scores derived from GWAS of these different phenotypes may measure the same genetic influence. However, the much lower empirical correlation between polygenic scores (r~0.2–0.3 in our study) means that conducting the same analysis using different scores could yield different results. Parallel findings across different polygenic scores suggest that it is the overlap among these scores that quantifies the substantive genetic influence. Methods are needed to integrate information from GWAS of different phenotypes with high genetic correlation (33). In theory, polygenic scores that measure overlap between GWAS results for genetically correlated phenotypes may provide a more precise estimate of genetic influence.

Regarding research on gene environment interplay, results highlight two study design issues. First, temporal resolution of environmental exposure measures may be critical. Depression is an episodic condition, including in older adults (3). Even persistent cases experience temporary remissions. Increases in depressive symptoms following stressful life events may attenuate over time, as is characteristic in bereavement (34). Our study could account for this attenuation because HRS recorded the date when a respondent died, allowing precise quantification of time-since-exposure for measures of depressive symptoms. We used statistical models designed for this type of data. This difference may account for why our study could detect gene-environment interplay effects in contrast to some previous analyses (10; 11). Future studies to detect gene-environment interplay may benefit from focus on stressful life events that can be located in specific temporal relation to the measurement of depressive symptoms (35).

A second study design issue is the question of whether polygenic scores make good tools for investigating gene-environment interplay in the first place. Polygenic scores have been proposed as a method to investigate gene environment interplay because, by aggregating information from across the genome, they quantify larger genetic effects as compared to individual variants and take on normal distributions (36). These properties match theoretical and empirical models of genetic influence on quantitative traits (37). However, it is argued that polygenic scores derived from GWAS naïve to environmental variation may quantify primarily genetic influences that do not vary across environments, although alternative GWAS designs are possible (38). Findings reported above suggest that polygenic scores derived from GWAS naïve to environmental variation can predict heterogeneity in response to environmental exposures.

This study has limitations. We studied depression in married older adults. Etiology of depression in older adults may differ in some ways from etiology in younger adults, although the relationship of stressful life events to depression does not seem to vary with age (39). Etiological features of depression, including subjective wellbeing may influence probability of marriage and of remaining married into later life. Replication of results in younger samples and with unmarried adults is needed. We studied depression following death of a spouse. Depression following death of a spouse may be different from depression related to other stressful life events. However, the distinction is unclear, as is reflected in the most recent revision of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (40). There is evidence that so-called bereavement-related depression shares etiology with depression related to other stressful life events (41). Tests of wellbeing polygenic score as a buffer against depressive symptoms following other types of stressful life events are needed. Our analysis was restricted to European-descent HRS participants because of concerns about generalizability of GWAS results across racial/ethnic populations (18). Studies of genetic buffering against depression following stressful life events in non-European populations are needed.

Research into interplay between genes and environments has a contentious history in psychiatry. With the advent of large-scale GWAS, new, more reliable genetic measures of liability to psychiatric disorders and other mental health characteristics are emerging. At the same time, genetic data are becoming available for large, population-based social surveys that have recorded environmental exposure information for participants. Together, these resources make possible a new generation of molecular genetic research into gene-environment interplay in the etiology of psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from the HRS, which is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (Grants NIA U01AG009740, RC2AG036495, and RC4AG039029) and conducted by the University of Michigan. Further support was provided by the NIH/NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (R24HD066613). DWB is supported by an Early Career Research Fellowship from the Jacobs Foundation and NIA grants R01AG032282, P30AG034424 and P30AG028716. AO is supported by ERC Consolidator Grant (647648 EdGe). This research was facilitated by the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (SSGAC).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez M-G, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bernabé E, Bhalla K, Bhandari B, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Black JA, Blencowe H, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Bonaventure A, Boufous S, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Braithwaite T, Brayne C, Bridgett L, Brooker S, Brooks P, Brugha TS, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Buckle G, Budke CM, Burch M, Burney P, Burstein R, Calabria B, Campbell B, Canter CE, Carabin H, Carapetis J, Carmona L, Cella C, Charlson F, Chen H, Cheng AT-A, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahiya M, Dahodwala N, Damsere-Derry J, Danaei G, Davis A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Dellavalle R, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani M, Diaz-Torne C, Dolk H, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Edmond K, Elbaz A, Ali SE, Erskine H, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ewoigbokhan SE, Farzadfar F, Feigin V, Felson DT, Ferrari A, Ferri CP, Fèvre EM, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Flood L, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FGR, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabbe BJ, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Ganatra HA, Garcia B, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gmel G, Gonzalez-Medina D, Gosselin R, Grainger R, Grant B, Groeger J, Guillemin F, Gunnell D, Gupta R, Haagsma J, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hall W, Haring D, Haro JM, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Higashi H, Hill C, Hoen B, Hoffman H, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Huang JJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jarvis D, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Jonas JB, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Keren A, Khoo J-P, King CH, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Laden F, Lalloo R, Laslett LL, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Lee YY, Leigh J, Levinson D, Lim SS, Limb E, Lin JK, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Liu W, Loane M, Ohno SL, Lyons R, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Manivannan S, Marcenes W, March L, Margolis DJ, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGill N, McGrath J, Medina-Mora ME, Meltzer M, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Meyer A-C, Miglioli V, Miller M, Miller TR, Mitchell PB, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Moffitt TE, Mokdad AA, Monasta L, Montico M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran A, Morawska L, Mori R, Murdoch ME, Mwaniki MK, Naidoo K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KMV, Nelson PK, Nelson RG, Nevitt MC, Newton CR, Nolte S, Norman P, Norman R, O’Donnell M, O’Hanlon S, Olives C, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Page A, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Patten SB, Pearce N, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Phillips D, Phillips MR, Pierce K, Pion S, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope CA, Popova S, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Prince M, Pullan RL, Ramaiah KD, Ranganathan D, Razavi H, Regan M, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Richardson K, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, De Leòn FR, Ronfani L, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Saha S, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Segui-Gomez M, Shahraz S, Shepard DS, Shin H, Shivakoti R, Singh D, Singh GM, Singh JA, Singleton J, Sleet DA, Sliwa K, Smith E, Smith JL, Stapelberg NJC, Steer A, Steiner T, Stolk WA, Stovner LJ, Sudfeld C, Syed S, Tamburlini G, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Taylor JA, Taylor WJ, Thomas B, Thomson WM, Thurston GD, Tleyjeh IM, Tonelli M, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris MK, Ubeda C, Undurraga EA, van der Werf MJ, van Os J, Vavilala MS, Venketasubramanian N, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weatherall DJ, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Weisskopf MG, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiebe N, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams SRM, Witt E, Wolfe F, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh P-H, Zaidi AKM, Zheng Z-J, Zonies D, Lopez AD, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. The Lancet. 2005;365:1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blazer DG. Depression in Late Life: Review and Commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M249–M265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC. The Effects of Stressful Life Events on Depression. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraaij V, Arensman E, Spinhoven P. Negative Life Events and Depression in Elderly Persons A Meta-Analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P87–P94. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.p87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol Bull. 1991;110:406–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silberg J, Rutter M, Neale M, Eaves L. Genetic moderation of environmental risk for depression and anxiety in adolescent girls. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:116–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic Sensitivity to the Environment: The Case of the Serotonin Transporter Gene and Its Implications for Studying Complex Diseases and Traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyrot WJ, Milaneschi Y, Abdellaoui A, Sullivan PF, Hottenga JJ, Boomsma DI, Penninx BWJH. Effect of polygenic risk scores on depression in childhood trauma. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:113–119. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullins N, Power RA, Fisher HL, Hanscombe KB, Euesden J, Iniesta R, Levinson DF, Weissman MM, Potash JB, Shi J, Uher R, Cohen-Woods S, Rivera M, Jones L, Jones I, Craddock N, Owen MJ, Korszun A, Craig IW, Farmer AE, McGuffin P, Breen G, Lewis CM. Polygenic interactions with environmental adversity in the aetiology of major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2016;46:759–770. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musliner KL, Seifuddin F, Judy JA, Pirooznia M, Goes FS, Zandi PP. Polygenic risk, stressful life events and depressive symptoms in older adults: a polygenic score analysis. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1709–1720. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okbay A, Baselmans BML, De Neve J-E, Turley P, Nivard MG, Fontana MA, Meddens SFW, Linnér RK, Rietveld CA, Derringer J, Gratten J, Lee JJ, Liu JZ, de Vlaming R, Ahluwalia TS, Buchwald J, Cavadino A, Frazier-Wood AC, Furlotte NA, Garfield V, Geisel MH, Gonzalez JR, Haitjema S, Karlsson R, van der Laan SW, Ladwig K-H, Lahti J, van der Lee SJ, Lind PA, Liu T, Matteson L, Mihailov E, Miller MB, Minica CC, Nolte IM, Mook-Kanamori D, van der Most PJ, Oldmeadow C, Qian Y, Raitakari O, Rawal R, Realo A, Rueedi R, Schmidt B, Smith AV, Stergiakouli E, Tanaka T, Taylor K, Wedenoja J, Wellmann J, Westra H-J, Willems SM, Zhao W, Amin N, Bakshi A, Boyle PA, Cherney S, Cox SR, Davies G, Davis OSP, Ding J, Direk N, Eibich P, Emeny RT, Fatemifar G, Faul JD, Ferrucci L, Forstner A, Gieger C, Gupta R, Harris TB, Harris JM, Holliday EG, Hottenga J-J, De Jager PL, Kaakinen MA, Kajantie E, Karhunen V, Kolcic I, Kumari M, Launer LJ, Franke L, Li-Gao R, Koini M, Loukola A, Marques-Vidal P, Montgomery GW, Mosing MA, Paternoster L, Pattie A, Petrovic KE, Pulkki-Råback L, Quaye L, Räikkönen K, Rudan I, Scott RJ, Smith JA, Sutin AR, Trzaskowski M, Vinkhuyzen AE, Yu L, Zabaneh D, Attia JR, Bennett DA, Berger K, Bertram L, Boomsma DI, Snieder H, Chang S-C, Cucca F, Deary IJ, van Duijn CM, Eriksson JG, Bültmann U, de Geus EJC, Groenen PJF, Gudnason V, Hansen T, Hartman CA, Haworth CMA, Hayward C, Heath AC, Hinds DA, Hyppönen E, Iacono WG, Järvelin M-R, Jöckel K-H, Kaprio J, Kardia SLR, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Kraft P, Kubzansky LD, Lehtimäki T, Magnusson PKE, Martin NG, McGue M, Metspalu A, Mills M, de Mutsert R, Oldehinkel AJ, Pasterkamp G, Pedersen NL, Plomin R, Polasek O, Power C, Rich SS, Rosendaal FR, den Ruijter HM, Schlessinger D, Schmidt H, Svento R, Schmidt R, Alizadeh BZ, Sørensen TIA, Spector TD, Steptoe A, Terracciano A, Thurik AR, Timpson NJ, Tiemeier H, Uitterlinden AG, Vollenweider P, Wagner GG, Weir DR, Yang J, Conley DC, Smith GD, Hofman A, Johannesson M, Laibson DI, Medland SE, Meyer MN, Pickrell JK, Esko T, Krueger RF, Beauchamp JP, Koellinger PD, Benjamin DJ, Bartels M, Cesarini D LifeLines Cohort Study. Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nat Genet. 2016;48:624–633. doi: 10.1038/ng.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 2000;55:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss A, Bates TC, Luciano M. Happiness is a personal (ity) thing the genetics of personality and well-being in a representative sample. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant F, Guille C, Sen S. Well-being and the risk of depression under stress. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium. Ripke S, Wray NR, Lewis CM, Hamilton SP, Weissman MM, Breen G, Byrne EM, Blackwood DHR, Boomsma DI, Cichon S, Heath AC, Holsboer F, Lucae S, Madden PAF, Martin NG, McGuffin P, Muglia P, Noethen MM, Penninx BP, Pergadia ML, Potash JB, Rietschel M, Lin D, Müller-Myhsok B, Shi J, Steinberg S, Grabe HJ, Lichtenstein P, Magnusson P, Perlis RH, Preisig M, Smoller JW, Stefansson K, Uher R, Kutalik Z, Tansey KE, Teumer A, Viktorin A, Barnes MR, Bettecken T, Binder EB, Breuer R, Castro VM, Churchill SE, Coryell WH, Craddock N, Craig IW, Czamara D, De Geus EJ, Degenhardt F, Farmer AE, Fava M, Frank J, Gainer VS, Gallagher PJ, Gordon SD, Goryachev S, Gross M, Guipponi M, Henders AK, Herms S, Hickie IB, Hoefels S, Hoogendijk W, Hottenga JJ, Iosifescu DV, Ising M, Jones I, Jones L, Jung-Ying T, Knowles JA, Kohane IS, Kohli MA, Korszun A, Landen M, Lawson WB, Lewis G, Macintyre D, Maier W, Mattheisen M, McGrath PJ, McIntosh A, McLean A, Middeldorp CM, Middleton L, Montgomery GM, Murphy SN, Nauck M, Nolen WA, Nyholt DR, O’Donovan M, Oskarsson H, Pedersen N, Scheftner WA, Schulz A, Schulze TG, Shyn SI, Sigurdsson E, Slager SL, Smit JH, Stefansson H, Steffens M, Thorgeirsson T, Tozzi F, Treutlein J, Uhr M, van den Oord EJCG, Van Grootheest G, Völzke H, Weilburg JB, Willemsen G, Zitman FG, Neale B, Daly M, Levinson DF, Sullivan PF. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, Weir DR. Cohort Profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:576–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlson CS, Matise TC, North KE, Haiman CA, Fesinmeyer MD, Buyske S, Schumacher FR, Peters U, Franceschini N, Ritchie MD, et al. Generalization and dilution of association results from European GWAS in populations of non-European ancestry: the PAGE study. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudbridge F. Power and predictive accuracy of polygenic risk scores. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conley D, Laidley T, Belsky D, Fletcher J, Boardman J, Domingue B. Assortative mating and differential fertility by phenotype and genotype across the 20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523592113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wray NR, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Prediction of individual genetic risk to disease from genome-wide association studies. Genome Res. 2007;17:1520–1528. doi: 10.1101/gr.6665407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci [Internet] Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13595. advance online publication[cited 2014 Jul 22] Available from: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nature13595.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zisook S, Shuchter SR. Depression through the first year after the death of a spouse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1346–1352. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74:829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindstrom MJ, Bates DM. Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models for Repeated Measures Data. Biometrics. 1990;46:673–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turvey CL, Carney C, Arndt S, Wallace RB, Herzog R. Conjugal Loss and Syndromal Depression in a Sample of Elders Aged 70 Years or Older. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1596–1601. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Anttila V, Gusev A, Day FR, Loh P-R, Duncan L, Perry JRB, Patterson N, Robinson EB, Daly MJ, Price AL, Neale BM ReproGen Consortium, Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Genetic Consortium for Anorexia Nervosa of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 3. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1236–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng.3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uher R. Gene–environment interactions in severe mental illness. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:48. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wray NR, Yang J, Hayes BJ, Price AL, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Pitfalls of predicting complex traits from SNPs. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:507–515. doi: 10.1038/nrg3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Foland-Ross LC. Understanding familial risk for depression a 25-year perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2014;9:94–108. doi: 10.1177/1745691613513469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smoller JW, Craddock N, Kendler K, Lee PH, Neale BM, Nurnberger JI, Ripke S, Santangelo S, Sullivan PF. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zisook S, Paulus M, Shuchter SR, Judd LL. The many faces of depression following spousal bereavement. J Affect Disord. 1997;45:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, Speller H, Chan G, Gelernter J, Guille C. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:557–565. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belsky DW, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Genetics in population health science: strategies and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 1):S73–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plomin R, Haworth CM, Davis OS. Common disorders are quantitative traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:872–878. doi: 10.1038/nrg2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boardman JD, Domingue BW, Blalock CL, Haberstick BC, Harris KM, McQueen MB. Is the gene-environment interaction paradigm relevant to genome-wide studies? The case of education and body mass index Demography. 2014;51:119–139. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessing LV, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Does the impact of major stressful life events on the risk of developing depression change throughout life? Psychol Med. 2003;33:1177–1184. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Psychiatric Association, others. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kendler KS, Myers J, Zisook S. Does bereavement-related major depression differ from major depression associated with other stressful life events? Am. J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1449–1455. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.