Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is unique from other cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) subtypes because of dyspigmentation and scarring, which are associated with quality of life (QoL) impairment in other skin disorders.1, 2 While previous QoL studies have included heterogeneous cohorts of patients with CLE, we focused on patients with DLE to identify clinical and demographic features that correlate with QoL impairment. We hypothesized that greater skin disease activity, skin disease damage, dark skin type, female gender, low socioeconomic status (defined by annual income), and current smoking status would be associated with poorer QoL in patients with DLE.

A cross-sectional pilot study was performed of 117 DLE patients consecutively enrolled between April 2010 and April 2014 in outpatient dermatology clinics in University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Health and Hospital System. Patients with a diagnosis of DLE based on clinical and/or histologic evidence and over 18 years of age were included. This study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Institutional Review Board. We collected demographic information, medications, disease history, and disease severity assessments (e.g. Cutaneous Lupus Activity and Severity Index (CLASI)). Patients completed the QoL questionnaire SKINDEX-29+3, which contained three additional lupus-specific questions about concerns of sun exposure, hair loss, and limitation of outdoor activities. These scores were primary outcomes, and high scores represented poor QoL.3

Patient characteristics were summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and as medians and 25th–75th percentile (interquartile range (IQR)) for continuous variables. Relationships between SKINDEX-29+3 domain scores and predictor variables (listed in Supplemental Table 1) were evaluated by univariable and multivariable regression analyses. In addition to independent variables with p-values of <0.05 in the univariable analyses (Supplemental Table 2), we selected six variables (e.g. gender, smoking, annual income, CLASI activity, CLASI damage, and skin type) based on prior literature4, 5 and clinical experience, to be included a priori in the multivariable analyses for each SKINDEX-29+3 domain. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Multivariable analyses (Table 1) revealed that female gender and current smoking status were significantly associated with poorer QoL in the SKINDEX-29+3 emotions domain. In the SKINDEX-29+3 functioning domain, we identified significant predictor variables including current smoking status, and lower annual income. Higher CLASI activity scores, female gender, and current smoking status significantly correlated with higher SKINDEX-29+3 symptoms scores. Female gender was significantly associated with higher SKINDEX-29+3 lupus-specific scores. High SKINDEX-29+3 scores in all four domains did not correlate with dark skin types and high CLASI damage scores.

Table 1.

SKINDEX-29+3 scores in DLE patients – multivariable analyses

| Emotions* | Functioning** | Symptoms# | Lupus-specific## | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| β-Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | β-Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | β-Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | β-Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

|

||||||||

| CLASI activity | −0.25 (−1.24 to 0.73) | NS | 0.25 (−0.70 to 1.21) | NS | 0.92 (0.17 to 1.67) | 0.02 | 0.73 (−0.34 to 1.80) | NS |

| CLASI damage | 0.53 (−0.41 to 1.47) | NS | 0.19 (−0.75 to 1.12) | NS | −0.06 (−0.79 to 0.68) | NS | −0.46 (−1.49 to 0.57) | NS |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 17.36 (3.74 to 30.98) | 0.01 | 9.90 (−2.90 to 22.71) | NS | 13.99 (3.86 to 24.11) | 0.007 | 23.81 (8.82 to 38.79) | 0.002 |

| Smoking status (current smokers vs. non-smokers) | 18.32 (7.52 to 29.13) | 0.001 | 13.83 (3.48 to 24.19) | 0.009 | 9.99 (1.84 to 18.14) | 0.02 | 7.38 (−4.41 to 19.17) | NS |

| Skin type group | --- | NS | --- | NS | --- | NS | --- | NS |

| I–II vs. V–VI | 2.39 (−14.42 to 19.20) | NS | 4.64 (−11.17 to 20.45) | NS | 1.81 (−10.62 to 14.24) | NS | −0.52 (−18.92 to 17.88) | NS |

| III–IV vs V–VI | −5.19 (−17.56 to 7.19) | NS | −5.71 (−17.36 to 5.93) | NS | −7.07 (−16.28 to 2.14) | NS | −5.84 (−19.46 to 7.77) | NS |

| Annual income | --- | NS | --- | 0.04 | --- | NS | --- | NS |

| <$10K vs. $10–50K | 0.90 (−12.11 to 13.91) | NS | 10.60 (−1.96 to 23.16) | NS | 6.31 (−2.96 to 15.58) | NS | 13.72 (0.25 to 27.19) | 0.046 |

| <$10K vs. >$50K | 11.31 (−5.05 to 27.68) | NS | 20.61 (4.92 to 36.31) | 0.01 | 10.66 (0.41 to 20.92) | 0.04 | 7.33 (−7.69 to 22.35) | NS |

| Marital status (married vs. non-married) | −2.82 (−15.94 to 10.30) | NS | −1.47 (−13.91 to 10.98) | NS | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Generalized vs. localized DLE∧ | --- | --- | 2.86 (−8.99 to 14.71) | NS | 2.84 (−6.44 to 12.11) | NS | --- | --- |

Model included CLASI activity, CLASI damage, gender, smoking status, skin type group, annual income, and marital status.

Model included CLASI activity, CLASI damage, gender, smoking status, skin type group, annual income, marital status, and generalized vs. localized DLE.

Model included CLASI activity, CLASI damage, gender, smoking status, skin type group, annual income, and generalized vs. localized DLE.

Model included CLASI activity, CLASI damage, gender, smoking status, skin type group, and annual income.

Generalized DLE is defined as having discoid lesions below the neck. Localized DLE is defined as having discoid lesions in the head and/or neck only.

Abbreviations: CLASI, Cutaneous lupus disease area and severity index; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; NS, not significant

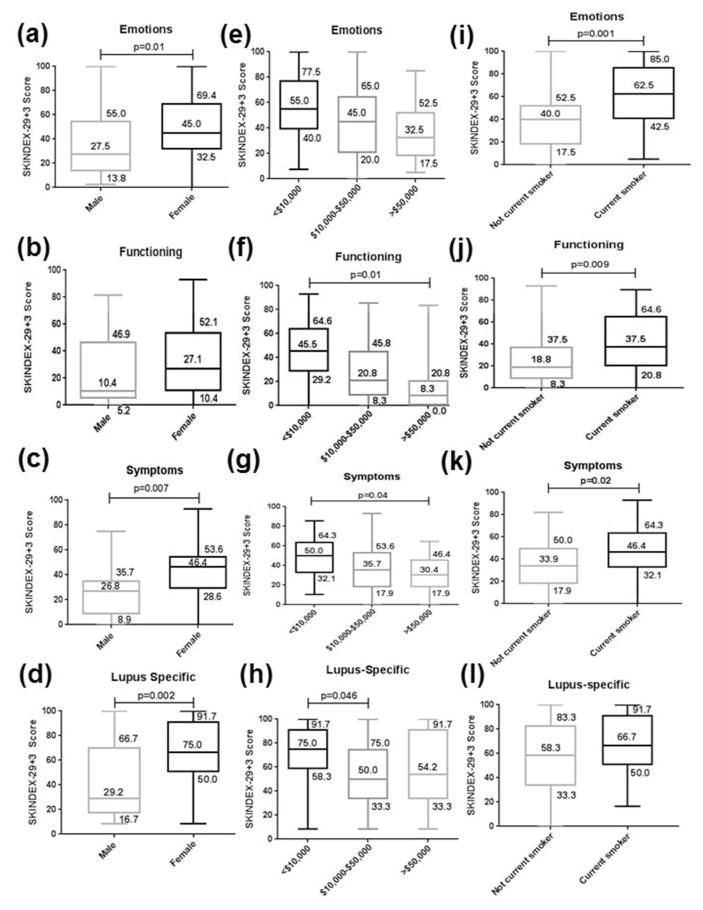

Fig. 1 provides box and whisker plots of significant predictor variables and their SKINDEX-29+3 scores. Female gender was associated with poorer QoL in DLE for the SKINDEX-29+3 emotions, symptoms, and lupus-specific domains (Fig. 1a–d). Reporting annual income less than $10,000 was associated with poorer QoL in the SKINDEX-29+3 functioning and symptoms domains versus those over $50,000, and in the SKINDEX-29+3 lupus-specific domain versus those between $10,000 and $50,000 (Fig. 1e–h). Current smokers had higher SKINDEX-29+3 scores than non-current smokers in the emotions, functioning, and symptoms domains (Fig 1i–l).

Fig. 1.

SKINDEX-29+3 scores in DLE patients sub-divided by gender, income level, and smoking status. SKINDEX-29+3 scores in emotions, functioning, symptoms, and lupus-specific domains were compared between DLE patients who were males (N=20) and females (N=97) (a–d), had annual incomes <$10,000 (N=41), $10,000–$50,000 (N=35), and >$50,000 (N=26) (e–h), and were current smokers (N=49) and not current smokers (N=68) (i–l). The lower and upper limits of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles (with values indicated), the line within the box depicts the median (with values indicated), and the whiskers (error bars) below and above the box indicate the minimum and maximum values.

Social factors may play a role in greater QoL impairment seen in female DLE patients. Females are more negatively affected by their hair loss and dyspigmentation in other skin diseases that present with these features such as cicatricial alopecias and vitiligo.6, 7 The negative effect of smoking on QoL in patients with DLE may reflect poor responsiveness to therapy such as anti-malarials,8 and a heightened inflammatory response.9 DLE patients with low socioeconomic status are at risk for poor QoL likely due to limited access to medical care, difficulty with transportation, lack of insurance, or inability to afford medications.

The lack of significant correlation between CLASI damage scores and SKINDEX-29 scores may be due to patients’ adjustment to their disease over time, as DLE patients may be impacted by disease activity more than by the permanent sequelae of their disease.10 The non-significant association of dark skin type and high SKINDEX-29 scores may reflect limitations in the SKINDEX-29+3 questionnaire, which does not contain numerous questions specific to dyspigmentation. In focus group sessions with patients with DLE, in which several had dark skin types, many noted the negative impact of their dyspigmentation and scarring through negative social perceptions and daily lifestyle adjustments to mask them (MO, BFC – unpublished observations). Thus, we are devising a disease-specific questionnaire for CLE that probes more into these concerns and would help track disease improvement in future clinical trials.

Our results highlight predictors of QoL impairment in DLE patients, including female gender, being a current smoker, and of lower socioeconomic status. Limitations include its cross-sectional nature, and location at two outpatient clinics, which restricted generalizability. Providers can ask those at risk for worse QoL additional questions probing emotions about their DLE, impact on daily life activities such as going outdoors, and severity of skin symptoms such as itching.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgements: The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AR061441, and by the National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001105. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas and its affiliated academic and health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to thank Rose Ann Cannon and Jack O’Brien for assisting in manuscript preparation and Drs. Rebecca Vasquez, Andrew Kim, Daniel Grabell, and Tina Vinoya for help in recruitment of patients.

Abbreviations

- CLASI

Cutaneous Lupus Disease Area and Severity Index

- CLE

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- DLE

Discoid lupus erythematosus

- QoL

Quality of life

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Chong is an investigator for Daavlin Corporation and Biogen Incorporated.

References

- 1.Bock O, Schmid-Ott G, Malewski P, Mrowietz U. Quality of life of patients with keloid and hypertrophic scarring. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:433–8. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ongenae K, Van Geel N, De Schepper S, Naeyaert JM. Effect of vitiligo on self-reported health-related quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein R, Moghadam-Kia S, Taylor L, et al. Quality of life in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:849–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasquez R, Wang D, Tran QP, et al. A multicentre, cross-sectional study on quality of life in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pradhan P, D’Souza M, Bade BA, Thappa DM, Chandrashekar L. Psychosocial impact of cicatricial alopecias. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:684–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amer AA, Gao XH. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo: an analysis of the dermatology life quality index outcome over the past two decades. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:608–14. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chasset F, Frances C, Barete S, Amoura Z, Arnaud L. Influence of smoking on the efficacy of antimalarials in cutaneous lupus: A meta-analysis of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:634–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills CM, Hill SA, Marks R. Altered inflammatory responses in smokers. BMJ. 1993;307:911. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6909.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma SM, Okawa J, Propert KJ, Werth VP. The impact of skin damage due to cutaneous lupus on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:315–21. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.