Abstract

Background

Data regarding the effect of a solitary kidney during pregnancy have come from studies of living kidney donors. We evaluated the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with a single kidney from renal agenesis.

Study Design

Matched cohort study.

Setting and Participants

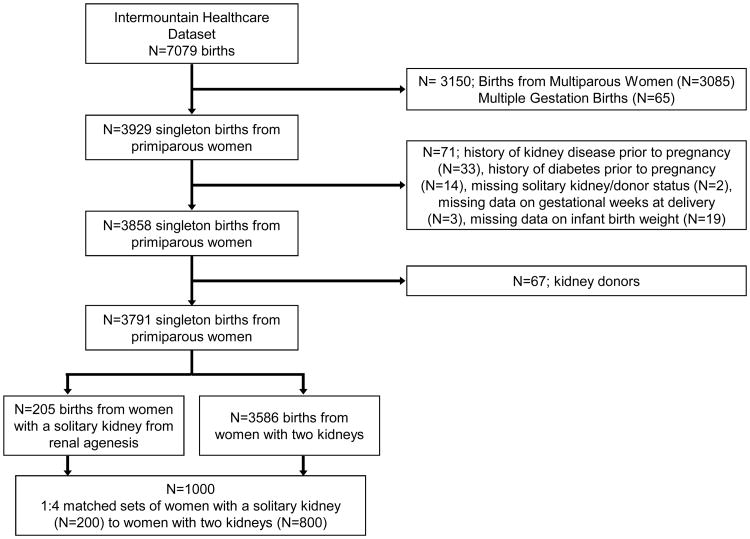

Using data from 7,079 childbirths from an integrated health care delivery system from 1996 through 2015, we identified births from women with renal agenesis. Only first pregnancies and singleton births were included. After excluding those with diabetes and kidney disease, a total of 200 women with renal agenesis were matched 1:4 by age (within 2 years), race, and history of hypertension to women with two kidneys.

Predictor

Renal agenesis defined by ICD-9 codes prior to pregnancy.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was adverse maternal outcomes including preterm delivery, delivery via cesarean section, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and length of stay at hospital. Adverse neonatal endpoints were considered as a secondary outcome and included low birth weight (<2,500 g) and infant death/transfer to acute inpatient facility.

Results

The mean gestational age at delivery was 37.9 ± 2.1 weeks for women with renal agenesis compared to 38.6 ± 1.8 weeks for women with two kidneys. Compared to women with two kidneys, those with renal agenesis had an increased risk of preterm delivery (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.86-4.45), delivery via cesarean section (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.49-2.99), preeclampsia/eclampsia (OR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.23-4.72), and length of stay >3 days (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.18-2.78). Renal agenesis was not significantly associated with an increased risk of infant death/transfer to acute facility (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 0.57-11.89) or with low birth weight after accounting for preterm delivery (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.76-5.88).

Limitations

Renal agenesis was identified by ICD-9 code not by abdominal imaging.

Conclusion

Women with unilateral renal agenesis have a higher risk of adverse outcomes in pregnancy.

Index words: solitary kidney, unilateral renal agenesis, pregnancy, adverse maternal outcome, preterm delivery, gestational age, low birth weight, adverse neonatal outcome, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, eclampsia, hospital length of stay, pregnancy complications

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health problem. It is estimated that the prevalence of CKD is around 3% in women of childbearing age,1 however, the presence of kidney disease is often underappreciated in pregnancy. CKD during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Recently, it has been shown that adverse outcomes occur even with only mild kidney damage and normal glomerular filtration rate (GFR).1-4

Women with a solitary kidney may be at high risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Data regarding the effect of a solitary kidney during pregnancy have come from studies of living kidney donors and kidney transplant recipients. Studies have found that maternal and neonatal outcomes in living donors is about equal to that of the general population.5,6 However, there is an increased risk of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia in kidney donors that in matched non-donors.5

The risk of complications in women with a solitary kidney from etiologies other than kidney donation may be different. There are important differences between the long-term renal outcomes of individuals with congenital solitary kidney and those of healthy adult kidney donors.7 Hence, despite normal kidney function, there may be subclinical defects of the congenital solitary kidney, which may lead to adverse outcomes. Using data from an integrated health care delivery system, we tested the hypothesis that women with a single kidney from renal agenesis have a higher risk of pregnancy complications compared to women with two functional kidneys.

Methods

Study Design

Using data from the Intermountain Healthcare Enterprise Data Warehouse, which incorporates comprehensive electronic health and administrative data, we conducted a matched cohort study of female patients hospitalized for childbirth between the years 1996 to 2015. Intermountain Healthcare is a non-profit organization serving the states of Utah and Idaho. Its facilities range from adult tertiary-level care centers to small rural clinics and hospitals and averages 130,000 admissions annually.8 The Administrative Casemix (ICD Codes) database has been used at Intermountain Healthcare for years for research population selection and quality improvement processes. ICD coding is entered by the Health Information Management Department. This department has several steps of data validation. The corrected data then interfaces to populate the Administrative Casemix database which resides in the Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW).

This project was reviewed by the Intermountain Healthcare IRB, Protocol #1040486 and was determined to be exempt from the federal rules governing human subjects research and informed consent was not required.

Study Population

We included all female patients hospitalized for childbirth who had clinical and administrative data available in the Intermountain Healthcare system. We included all mother-infant pairs from singleton live births to primiparous women (Figure 1). Women with unilateral renal agenesis were identified by the ICD-9 code for renal agenesis (753.0). All women had a diagnosis of renal agenesis prior to pregnancy. Women with only one kidney due to kidney donation (n=75), those with a history of CKD (n=33), those with a history of diabetes (n=14), and those with multiple gestation (n=65) were excluded from the analysis. A woman was considered to have CKD if a Charlson ICD-9 code for kidney disease (582.x, 583-583.7, 585.x, 586.x, 588.x)9 existed prior to pregnancy or in the first trimester and/or if an ICD-9 code for proteinuria (791)9 existed prior to pregnancy.10 We identified 205 women with renal agenesis and normal kidney function. We performed a random chart review of 87 women included in this cohort to confirm the diagnosis of renal agenesis. Of the 37 patients with an ICD-9 code for renal agenesis, upon chart review we found that all had documentation of a single/solitary/absent kidney. Of the 50 patients that did not have an ICD-9 code for renal agenesis we found that two patients had physician documentation of a single functioning kidney, which in one case was due a previous nephrectomy. Hence we had approximate 4% (95% CI, **-**) miscoding of patients in our cohort.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram.

Matching

Using a pool of 3,586 women with two kidneys, women with unilateral renal agenesis were matched 1:4 to women with two kidneys by age at delivery (within 2 years), race, and history of chronic hypertension. A woman was considered to have chronic hypertension if an ICD-9 code for this comorbidity existed. Approach of nearest available neighbor matching without replacement was used.11 First, we randomly sorted cases (renal agenesis) and controls (two kidneys). Next, the first case was selected to find its closest control match based on age, race, and history of hypertension. The closest control was selected as a match and then that control was removed from the pool of available controls. This procedure was repeated for all of the women with renal agenesis. Of the 205 women with renal agenesis selected for matching, 200 (97.6%) could be matched to 4 women with two kidneys and were included in the analysis.

Outcomes

Outcomes were chosen based on previous studies examining adverse outcomes in pregnancy.12 Adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes were the primary and secondary outcome of this analysis, respectively. Adverse maternal outcomes included: 1) preterm delivery examined as: a) binary outcome (delivery <37 weeks vs. ≥ 37 weeks); and b) a three-category outcome: early preterm delivery (< 34 weeks) vs. late preterm delivery (34-36 weeks) vs. ≥ 37 weeks; 2) delivery via cesarean section; 3) longer length of maternal stay at the hospital (length of stay > 3 days); 4) combined outcome of preeclampsia and eclampsia identified by ICD-9 code (outcome was combined given the low number of patients with eclampsia). Adverse neonatal outcomes were defined as: 1) low infant birth weight (< 2500 grams); and 2) combined outcome of infant death and/or infant transfer to an acute inpatient facility.

Sensitivity Analysis

To determine if gestational age was driving low birth weight, we rematched the population by full-term birth, and performed a sensitivity analysis for low birth weight since lower birth weight may simply be due to earlier gestational age at delivery. If women with renal agenesis and full-term births did not have a significantly increased risk of having a low birth weight infant, this would suggest that the preterm births were primarily driving the low birth weight, since the other adverse pregnancy outcomes do not have as strong of a relationship to preterm delivery.

We excluded all of the women with preterm births and identified 162 women with renal agenesis and 3270 controls. We then matched full-term birth women 1:4 by age at delivery (within 2 years), race and history of hypertension to women with two kidneys. Four women with renal agenesis could not be matched to a control: two of them we could not identify a matched control, for one of them only 1 matched control could be found and for the other woman only 2 matched controls could be found.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of the women with unilateral renal agenesis and two kidneys. Means with standard deviations were used for continuous data and frequencies and proportions were used for categorical data. With matched set data, conditional logistic regression models were employed in analysis of binary outcome and multinomial logistic model (also known as multivariate binary model)13 was employed in analysis of outcome of three categories (early preterm birth if gestational weeks was <34 weeks, late preterm birth if gestational weeks was 34 to 36 weeks, and full-term birth if gestational weeks was 37 or greater). All analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). The reporting of this observational study was based on the recommendations in the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.14

Results

We identified 200 women with a solitary kidney from renal agenesis (Figure 1). These women were matched 1:4 by age, race, and history of chronic hypertension with women with two kidneys (N=800). The mean (SD) age was 26.9 ± 5.7 years in women with renal agenesis and 27.2 ± 5.3 years in women with two kidneys. As seen in Table 1, the women with unilateral renal agenesis were well matched with women with two kidneys. The majority of the women were white (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics (matching covariates) of Women with Unilateral Renal Agenesis or Women with Two Kidneys before and after matching.

| Characteristic | Women with Unilateral Renal Agenesis (N=200) | Matched Women with 2 Kidneys (N=800) | Entire Control Population of Women with 2 Kidneys (N=3586) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (y) | 26.9 ± 5.7 | 27.2 ± 5.3 | 27.7 ± 5.4 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 187 (93.5) | 748 (93.5) | 3230 (90.1) |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 18 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 12 (6.0) | 48 (6.0) | 199 (5.5) |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 16 (8.0) | 64 (8.0) | 211 (5.9) |

Values given as mean ± standard deviation or count (percentage).

The prevalence of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes is shown in Table 2. The mean gestational age at delivery was 37.9 ± 2.1 weeks for women with unilateral renal agenesis and 38.6 ± 1.8 weeks for women with two kidneys. Women with unilateral renal agenesis were more likely to have preterm delivery than women with two kidneys (20.5% vs. 8.5%, p< 0.001). The mean gestational age of preterm infants was 34.6 ± 2.0 weeks for women with unilateral renal agenesis compared to 34.4 ± 2.5 weeks for women with two kidneys. The majority of preterm births were late preterm births (87 late preterm births out of the total 109 preterm births). Women with unilateral renal agenesis had a higher prevalence of both late preterm birth (16.5% vs. 6.8%, p<0.001) and early preterm birth (4.0% vs. 1.8%, p<0.001) than women with two kidneys. Women with unilateral renal agenesis were also more likely to have delivery via cesarean section (33.5% vs. 19.6%, p<0.001), preeclampsia/eclampsia (7.0% vs. 3.0%, p=0.01) and a length of stay >3 days (18.5% vs. 11.4%, p=0.01) than women with two kidneys (Table 2). Women with unilateral renal agenesis had a higher prevalence of low birth weight (16.5% vs. 5.6%, p<0.0001). In addition, infant death/transfer to an acute inpatient facility was also higher in women with unilateral renal agenesis but it did not reach statistical significance (1.5% vs. 0.6%, p=0.2).

Table 2. Association of Unilateral Renal Agenesis with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes.

| Outcome | N (%) | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal Agenesis (N=200) | Two Kidneys (N=800) | |||

|

| ||||

| Preterm Delivery (< 37 weeks) | 41 (20.5) | 68 (8.5) | <0.001 | 2.88 (1.86 to 4.45) |

| Early preterm (< 34 weeks) | 8 (4.0) | 14 (1.8) | 2.34 (0.95 to 5.74) | |

| Late preterm (34-36 weeks) | 33 (16.5) | 54 (6.8) | 2.73 (1.70 to 4.38) | |

| Delivery via Cesarean Section | 67 (33.5) | 157 (19.6) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.49 to 2.99) |

| Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | 14 (7.0) | 24 (3.0) | 0.01 | 2.41 (1.23 to 4.72) |

| Length of stay > 3 days | 37 (18.5) | 91 (11.4) | 0.01 | 1.81 (1.10 to 2.78) |

| Infant death/transfer to facility | 3 (1.5) | 5 (0.6) | 0.2 | 2.60 (0.57 to 11.89) |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 33 (16.5) | 45 (5.6) | <0.001 | 3.39 (2.08 to 5.54) |

Note: ORs and their 95% CIs were not calculated directly based on number in the table but from conditional logistic regression models because of the nature of matched set data.

The association of unilateral renal agenesis with adverse outcomes is shown in Table 2. Compared to women with two kidneys, those with unilateral renal agenesis had over a two-fold increased odds of preterm delivery (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.86-4.45). When preterm delivery was categorized as late preterm, compared to women with two kidneys, those with unilateral renal agenesis had a higher risk of having a late preterm delivery (OR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.70-4.38). Women with unilateral renal agenesis had a nominally increased risk of early preterm delivery compared to women with two kidneys, but this finding did not reach statistical significance (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 0.95-5.74; p=0.06). Women with unilateral renal agenesis also had a two-fold increased risk both of delivery via cesarean section and also of preeclampsia/eclampsia compared to women with two kidneys. Women with unilateral renal agenesis also had a higher risk of a length of stay in the hospital > 3 days compared to women with two kidneys. Women with unilateral renal agenesis had a 3-fold increased risk of having a low birth weight infant compared to women with two kidneys. Unilateral renal agenesis was not significantly associated with an increased risk of infant death or transfer to an acute facility (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 0.57-11.89).

We performed a sensitivity analysis to examine whether the higher risk of lower birth weight in women with unilateral renal agenesis was independent of gestational age. After excluding all preterm births, we identified 162 full-term birth mothers with unilateral renal agenesis and were able to match 158 of these women 1:4 by age at delivery (within 2 years), race and history of hypertension with women with two kidneys. Women with renal agenesis no longer had a significantly increased risk of a low birth weight infant compared to women with two kidneys (p=0.2); however, the magnitude of the association was consistent with a 2-fold increased risk (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.76-5.88).

Discussion

We found that non-diabetic women with a solitary kidney from renal agenesis with normal kidney function have a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes then women with two kidneys after matching by age, race and history of hypertension. Unilateral renal agenesis was significantly and independently associated with preterm delivery, delivery via cesarean section, preeclampsia/eclampsia, length of stay > 3 days, and low birth weight.

Pregnancy after kidney donation is associated with a small risk of adverse outcomes compared to women who are very low risk, but overall the risk of adverse complications is similar to that in the general population.5,6 Our data show that women with unilateral renal agenesis have a much higher risk of pregnancy-related complications compared to other women of similar age and comorbidities despite normal kidney function and lack of proteinuria.

Long-term renal outcomes are strikingly different in those with congenital single kidneys and those with single kidneys due to kidney donation. The risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease after kidney donation is less than 0.6% at 12 years.15 In children with a congenital cause of solitary kidney, nearly 50% require dialysis by 30 years of age.7 In a study of adults with renal agenesis with normal kidney function, absence of proteinuria and no structural abnormalities of the remaining kidney at the time of diagnosis, 47% developed hypertension, 13% had a decrease in GFR, and 4% died of kidney failure.16 These data suggest that renal agenesis is associated with subclinical defects that result in adverse renal outcomes as well as adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Several studies have found an association between CKD and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Not surprisingly, more pronounced kidney function decline is associated with more severe pregnancy complications. However, even women with mild kidney damage and normal kidney function (CKD stage 1) still have an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. In a recent study of normotensive pregnant women who were not obese, not diabetic, and did not have nephrotic-range proteinuria, those with CKD stage 1 (evidence of kidney damage (e.g. urinalysis or radiologic findings) but preserved GFR) had a higher risk of preterm birth, lower birth weight and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.4 In our cohort, we also did not have any women with diabetes and all of the participants had normal kidney function. Additionally, in our study none of the women had proteinuria at baseline. Hence, these women had no kidney disease progression risk factors at the start of pregnancy. In a sensitivity analysis we found that the higher risk of low birth weight was mainly driven by preterm births. However, in women with renal agenesis who had full-term births, there was still a nominal association an increased risk of low birth weight. The lack of a significant association may be due to the low number of events.

While the cause of the increased pregnancy complications is unknown, it may be due to lack of kidney function reserve during pregnancy. Pregnancy is associated with a dramatic increased in GFR and renal blood flow that begins early in gestation (first 2 weeks) and continues until delivery. This phenomenon is known as the hyperfiltration response. A decrease or perhaps lack of this hyperfiltration response in pregnant women with kidney disease might lead to poor pregnancy outcomes.17-19 However, a recent study of pregnant patients with CKD stage 1 did not find any difference in pregnancy-related outcomes between patients with or without a hyperfiltration response.4 Hence, other mechanisms such as endothelial damage, inflammation, and oxidative stress (all of which occur even with mild kidney damage) may be contributing to adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with early stage CKD.

Our study has some limitations. Since this is an observational study, a causal relationship between a congenital solitary kidney and adverse pregnancy outcomes cannot be established. Second, since this is a secondary analysis, we identified women with renal agenesis by ICD-9 code not abdominal imaging and used administrative data to identify the maternal and neonatal outcomes. Additionally, we identified hypertension, diabetes, proteinuria, and kidney function by ICD-9 code. The importance of these variables on pregnancy outcomes has been well described1-4,12,20,21 and miscoding of these data may have occurred in the dataset. Approximately 30% of women with unilateral renal agenesis have associated uterine/mullerian anomalies,22 which can contribute to preterm births and to increased cesarean sections (due to malpresentation).23 We did not have information on whether any of the women had associated uterine/mullerian anomalies nor did we have information on the indication for cesarean section. Additionally, it is possible that the increased rate of preterm delivery in women with renal agenesis was due to physician intervention rather than preterm labor24 and we do not have any information on whether the preterm births were indicated or spontaneous deliveries. However, since multiple sites from the Intermountain Healthcare system were included, the higher rate of preterm births is unlikely due to individual center practice. We recognize that body mass index (BMI) and smoking may play a role in pregnancy outcomes but unfortunately these variables were not available in our database. Since we identified preeclampsia/eclampsia by ICD-9 code it is possible that women were misclassified. We also lacked information on reflux nephropathy. Finally, the majority of women in the study were of white race so caution should be used when extrapolating these results to other populations.

Not withstanding these limitations, our study also has several strengths. First, we were able to examine the association between a solitary kidney from an etiology other than kidney donation and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Second, we were able to match women on parity and only include primiparous women to reduce bias towards delivery modes, since women who have had a prior preterm birth are at a higher risk of a recurrent preterm birth and women who have had a prior cesarean section may not be a candidate for an attempt at a vaginal birth after cesarean section. Additionally, we excluded women with reduced kidney function, diabetes, or proteinuria, thus removing additional important confounders that may affect pregnancy outcomes. We used data from a large healthcare system with complete laboratory and administrative data; this database has been used for other published studies.12,25 Hence, we were able to identify over 200 women with renal agenesis and match them to 800 women with two kidneys.

In conclusion, our data indicate that a solitary kidney from renal agenesis is a significant and independent risk factor for adverse outcomes in pregnancy. Women with renal agenesis with normal kidney function and absence of proteinuria should be considered at high risk for adverse pregnancy-related complications and pre-conception counseling should be similar to that performed in women with kidney disease and reduced GFR.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Qing Li for her assistance in editing the manuscript.

This work was presented as a poster presentation at the American Society of Nephrology Annual Meeting in San Diego, CA, November 2015.

Support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) grants K23 DK087859 (Kendrick) and 1R01DK081473 (Chonchol). The NIDDK did not have any role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, writing the report or the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: JK, MC; Data acquisition: JH, JK, MC; Data analysis and interpretation: JK, MC, ZY, JH; Statistical analysis: ZY, GS; Supervision or mentorship: JK, MC. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Williams D, Davison J. Chronic kidney disease in pregnancy. BMJ. 2008;336(7637):211–215. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39406.652986.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piccoli GB, Attini R, Vasario E, Conijn A, et al. Pregnancy and chronic kidney disease: a challenge in all CKD stages. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5):844–855. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07911109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nevis IF, Reitsma A, Dominic A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(11):2587–2598. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10841210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piccoli G, Attini R, Vigotti FN, et al. Is renal hyperfiltration protective in chronic kidney disease-stage 1 pregnancies? A step forward unraveling the mystery of the effect of stage 1 chronic kidney disease on pregnancy outcomes. Nephrology. 2015;20(3):201–208. doi: 10.1111/nep.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg AX, McArthur E, Lentine KL. Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):124–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1501450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim HN, Akkina SK, Lesiter E, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(4):825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanna-Cherchi S, Ravani P, Corbani V, et al. Renal outcome in patients with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int. 2009;76(5):528–533. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Intermountain Healthcare. Annual Report. [Last accessed October 14 2016];2015 Available at: https://intermountainhealthcare.org/assets/PDF/annualreport2015.pdf.

- 9.American Medical Association. Hospital International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification Codes. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coca-Perraillon M. Matching with propensity scores to reduce bias in observational studies. Proceedings of the Northeast SAS Users Group (NESUG); September 2006; [Accessed September 14, 2016]. Available at: http://www.lexjansen.com/nesug/nesug06/an/da13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendrick J, Sharma S, Holmen J, Palit S, Nuccio E, Chonchol M. Kidney disease and maternal outcomes in pregnancy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(1):55–59. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuss O, McLerran D. A note on the estimation of the multinomial logistic model with correlated responses in SAS. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;87(3):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzshe PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Norden G, Lennerling A, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease among live kidney donors. Transplantation. 2006;82(12):1646–1648. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250728.73268.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argueso LR, Ritchey ML, Boyle ET, Jr, Milliner DS, Bergstrailh EJ, Kramer SA. Prognosis of patients with unilateral renal agenesis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1992;6(5):412–416. doi: 10.1007/BF00873996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baylis C. Glomerular filtration rate in normal and abnormal pregnancies. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19(2):133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heguilen RM, Liste AA, Belllusci AD, Lapidus AM, Bernasconi AR. Renal response to an acute protein challenge in pregnant women with borderline hypertension. Nephrolgy (Carlton) 2007;12(3):254–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livi R, Guiducci S, Perfetto F, et al. Lack of activation of renal functional reserve predicts the risk of significant renal involvement in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1963–1967. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.152892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ankumah NE, Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy: Diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60(1):206–214. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh H, Murphy HR, Hendrieckx C, Ritterband L, Speight J. The challenges and future considerations regarding pregnancy-related outcomes in women with preexisting diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(6):869–876. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0417-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S. Association of renal agenesis and mullerian duct anomalies. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24(6):829–834. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein AL, March CM. Pregnancy outcome in women with mullerian duct anomalies. J Reprod Med. 1990;35(4):411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccoli GB, Cabiddu G, Attini R, et al. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8):2011–2022. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones J, Holmen J, De Graauw J, Jovanovich A, Thornton S, Chonchol M. Association of complete recovery from acute kidney injury with incident CKD stage 3 and all-cause mortality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):402–408. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]