Abstract

Objective

To explore the impact of dual targeting of C-C motif chemokine receptor-2 (CCR2) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) on the metabolic and inflammatory consequences of high fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity.

Methods

C57BL/6J wild type (WT), Cx3cr1−/−, Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− double knockout male and female mice were fed a 45% HFD for up to 25 weeks starting at 12-weeks of age.

Results

All groups gained weight at a similar rate and developed similar degree of adiposity, hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance and impairment of insulin sensitivity in response to HFD. As expected, the circulating monocyte count was decreased in Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−, but not in Cx3cr1−/− Mice. Flow cytometric analysis of perigonadal adipose of male, but not female, mice revealed trends to lower CD11c+MGL1− M1- like macrophages and higher CD11c−MGL1+ M2- like macrophages as a percentage of CD45+F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages in Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice vs. WT mice, suggesting reduced adipose tissue macrophage activation. In contrast, single knockout of Ccr2 or Cx3cr1 did not differ in their adipose macrophage phenotypes.

Conclusion

Although CCR2 and CX3CR1 may synergistically impact inflammatory phenotypes, their joint deficiency did not influence metabolic effects of 45% HFD-induced obesity in these model conditions.

Keywords: Obesity, Glucose, Inflammation, Macrophages, Adipose Tissue

Introduction

Obesity-associated chronic inflammation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance, diabetes and cardiometabolic diseases (1). Obese adipose tissue demonstrates increased infiltration of immune cells (2). In particular, adipose macrophages, the most abundant inflammatory cells in obese adipose tissue and largely derived from infiltration of circulating monocytes, form “crown-like structures” around dead adipocytes, a feature associated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk (3).

Chemokines and their receptors play pivotal roles in tissue trafficking of leukocytes and therefore are of particular interest in obesity-associated inflammation and metabolic dysregulation (4). The chemokine receptor C-C receptor type 2 (CCR2) and its ligand C-C motif chemokine ligand-2 (CCL2, or monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) modulate monocyte/macrophage chemotaxis and local inflammatory responses (5). Adipose tissue expression and circulating levels of CCL2 were increased in obese rodents and humans (6, 7). In 60% high-fat diet (HFD; 60% calories from fat) fed mice, CCR2 deficiency attenuated the development of obesity, adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and systemic insulin resistance (5). Fractalkine (CX3CL1) is another adipocyte-derived inflammatory chemokine with higher expression in obese adipose tissue, and elevated plasma levels in diabetic subjects (8). Interaction of CX3CL1 and its receptor CX3CR1 mediates leukocyte adhesion (9).

CCR2 and CX3CR1 are differentially expressed on two major subsets of blood monocytes (10, 11). In mice, Ly6cLow monocytes lack CCR2 but express high levels of CX3CR1, and are long-lived, patrolling leukocytes that give rise to tissue macrophages under homeostatic conditions (12). Conversely, Ly6CHigh subsets of inflammatory monocytes express CCR2 and low levels of CX3CR1, and are short-lived and migrate rapidly from the circulation into inflamed tissues (13). CCR2 is the major regulator of Ly6CHigh monocyte trafficking (14), while CX3CR1 facilitates Ly6CLow monocyte adhesion to and patrolling of endothelial cells (12). Mice lacking either Ccl2, Cx3cr1 or Ccr5 have attenuated atherosclerosis with the combinations of knockouts of the three genes demonstrating a more pronounced protective phenotype (15), supporting the idea that these chemokine pathways act in an additive manner in atherogenesis.

The impact, however, of dual targeting of the CX3CR1/CX3CL1 and CCR2/CCL2 systems on the metabolic and inflammatory consequences of obesity have not been examined. We hypothesized that, because of the attenuation of monocyte tissue recruitment, dual targeting of CX3CR1 and CCR2 would exert additive effects on HFD-induced adipose tissue inflammation and related weight gain, glucose intolerance and systemic insulin resistance. To our surprise, although combined CCR2 and CX3CR1 deficiency showed reduction in circulating monocytes and modest reduction in proportion of M1-like adipose tissue macrophages coincident with reciprocal increase of M2-like macrophages, their joint deficiency had no impact on the metabolic consequences of HFD and obesity. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to address synergistic impact of dual targeting of CCR2 and CX3CR1 on obesity-related metabolic and inflammatory traits in mice.

Methods

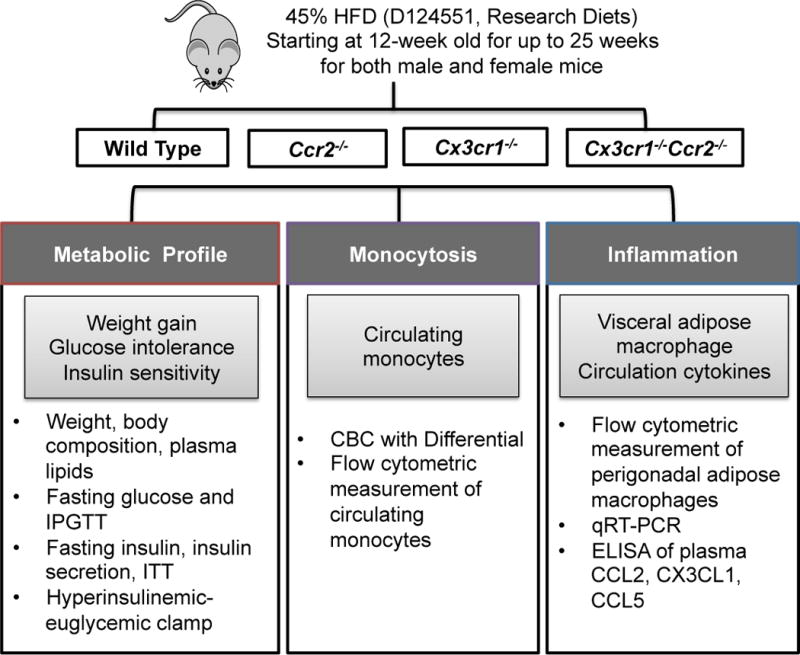

We compared metabolic and inflammatory phenotypes of mice with genetic deficiency of Cx3cr1, Ccr2, or both to their C57BL/6J Wild-Type (WT) littermates during extended periods of high-fat feeding (45% calories from fat for 25 weeks) as previously reported in studies utilizing single Ccr2−/− (5, 16) and Cx3cr1−/− mice (17). Specifically, we examined 1) body weight, body composition and plasma lipid profile, 2) fasting glucose concentrations and glucose intolerance, 3) baseline and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and peripheral insulin sensitivity by insulin tolerance test (ITT) and hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp; 4) circulating monocyte counts; 5) adipose tissue macrophage accumulation and activation and circulating levels of cytokines (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A schematic figure of the study design.

HFD, high-fat diet; IPGTT, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test; ITT, insulin tolerance test; CBC, complete blood count.

Diet-induced obesity

Ccr2−/− mice were generated by replacing the first 279 base pairs of the Ccr2 gene with a monomeric red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporter gene (18). Cx3cr1−/− mice were generated by replacing the first 390 base pairs of the Cx3cr1 gene with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter gene (19). Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− double knockout mice (a gift from Dr. Charo) were generated by crossing Ccr2−/− mice with Cx3cr1−/− mice (18). Both male and female mice were used and analyzed separately because of known sex differences in metabolic responses to high fat feeding in rodents. Beginning at 12-weeks of age, the mice were fed a high-fat high-sucrose diet with 45% calories from fat (45% HFD, D12451, Research Diets) for up to 25 weeks.

Body weight, body composition

Body weight was monitored and body composition was measured by 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Echo MRI, Houston, TX) after a 5-hour fasting (17).

Glucose homeostasis

Fasting blood glucose level and intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) with 20% glucose at 2 g/kg were measured in tail blood using glucometer (AlphaTRAK, Abbott Laboratories, Alameda, CA) at 8 AM after an overnight (16-hour) fast. Fasting insulin levels and glucose-induced insulin secretion (20% glucose at 1 g/kg) were measured after an overnight fast using tail blood plasma samples and ultra-sensitive mouse insulin ELISA (Crystal Chem Inc, Downers Grove, IL).

Insulin tolerance test (ITT) and hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp

Insulin tolerance test (ITT) (1 U/kg insulin) (17) and hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp were performed after a 5–6 hour fast as published (20, 21, 22).

Complete blood count analysis with differential

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential was analyzed with Sysmex XT-2000iV Automated Hematology Analyzer using EDTA-treated whole blood.

Adipose flow cytometry

As described (17), perigonadal adipose stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells were separated from mature adipocytes by digesting with Type I collagenase. After blocking by Fc block (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), cells were stained with the following antibodies: CD45-FITC, Ter119-PE, F4/80-PE-Cy7, CD11c-APCeF780, and CD11b-AF700 (eBioscience) and CD301(MGL1)-AF647 (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and run on a BD LSRII. Data were analyzed by FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc. Ashland, OR).

Statistical analyses

Sample size calculations were performed to determine the minimum number of mice per group. Based on results of a pilot study on 45% HFD-fed WT mice showing fasting blood glucose levels of 100.3±13.5 mg/dl (mean±SD), a sample size of n=8 would be adequate to ensure 80% power to detect a 20 mg/dl difference in mean fasting blood glucose levels, assuming a two-sided test and α of 0.05. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 and data were expressed as mean±SEM. For single time point measurement, statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t-test for two groups, and one-way ANOVA for more than two groups followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test to compare each group with WT mice unless otherwise documented. For repeated measurements (weight, IPGTT, glucose-induced insulin secretion and ITT), two-way ANOVA tests for repeated measurement followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test were performed.

The on-line supplement, including supplemental figures, provides additional methods and results.

Results

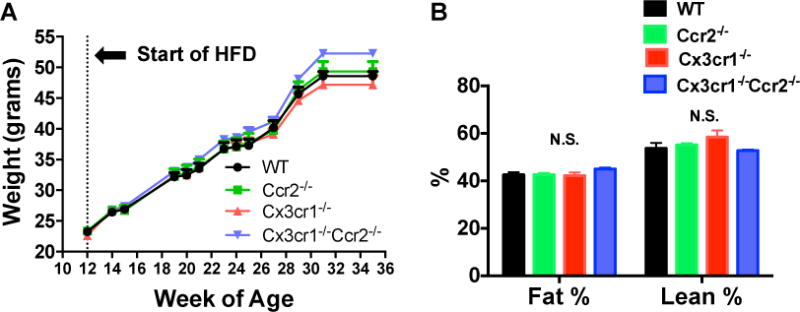

Deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both did not affect weight gain or body composition in male mice on HFD

We have previously shown that 45% HFD induced marked weight gain, glucose intolerance and increase visceral adipose tissue macrophage infiltration in male C57BL/6J WT mice (17). In the current study, male WT, Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice were fed with 45% HFD starting at 12-weeks of age, and body weight was recorded over time. All groups gained equal weight on HFD with no evidence of differences between groups (Figure 2A). The body composition was also similar between groups (Figure 2B). Plasma lipid profile showed marginal reduction in total cholesterol but not HDL-C and triglyceride in Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice vs. WT mice (Figure S1). The results suggested that in male mice, deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both had no meaningful impact on changes in body weight and body composition induced by a 45% HFD.

Figure 2. Deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both had no effects on weight gain or body composition in HFD-fed male mice.

Male WT, Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice were fed with 45% HFD (45% calories from fat) starting at 12-weeks of age. A: Weight gain over 25 weeks of feeding with 45% HFD was identical between groups (n=12 WT, 12 Ccr2−/−, 9 Cx3cr1−/−, 16 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). B: After 25 weeks of HFD feeding, body fat and lean mass were measured by NMR after a 5-hour fast and there were no differences between groups (n=9 WT, 10 Ccr2−/−, 8 Cx3cr1−/−, 17 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). Data are mean±SEM. N.S., not significant.

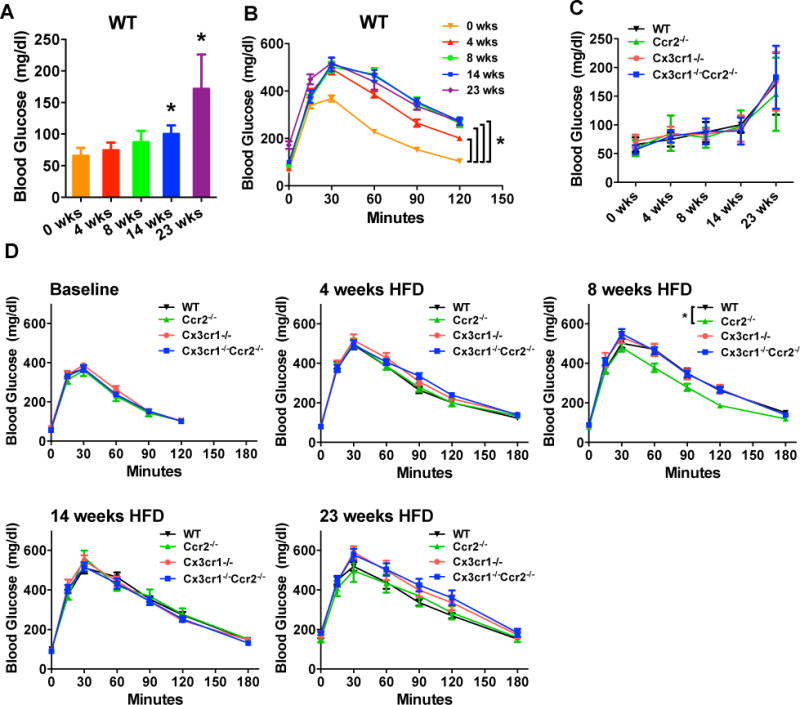

Deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both did not affect HFD-induced hyperglycemia or glucose intolerance in male mice

HFD feeding increased fasting glucose levels and impaired glucose tolerance in WT mice (Figure 3A–B). This HFD-induced hyperglycemia was also observed in Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice, and did not differ between groups (Figure 3C). Similarly, glucose intolerance, measured by IPGTT, in all groups did not differ by genotype at 4, 8, 12, and 23 weeks of HFD (Figure 3D). The only trend was in Ccr2−/− mice with slight attenuation of glucose intolerance at 8 weeks of HFD, but this effect was not observed outside this single time-point. Overall, the results suggest that deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both did not affect fasting hyperglycemia or glucose intolerance induced by HFD feeding in male mice.

Figure 3. Deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both did not modulate HFD-induced hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance in male mice.

Fasting blood glucose levels and IPGTT after an overnight fast were measured prior to and after 4, 8, 14 and 23 weeks of HFD in male WT, Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice (n=11 WT, 11 Ccr2−/−, 9 Cx3cr1−/−, 14 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). A and B: Fasting glucose levels were increased and glucose tolerance was impaired in WT mice by HFD. C and D: Fasting glucose levels or glucose tolerance were similarly affected by HFD between groups (two-way ANOVA analysis), although at 8 weeks of HFD, Ccr2−/− mice showed difference in glucose tolerance at a single-time point. Data are mean±SEM. *, P<0.05 vs. male WT mice.

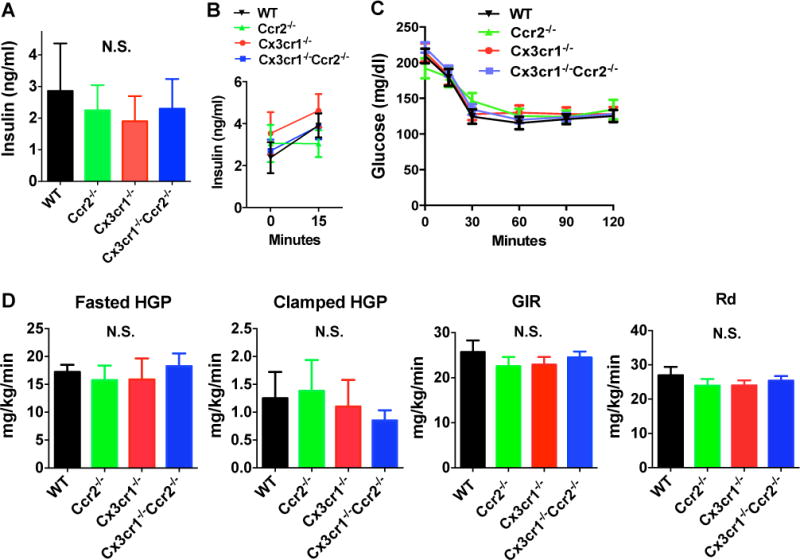

Deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both did not affect baseline and stimulated insulin secretion or insulin sensitivity in male mice

In the absence of effects of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 deficiency on HFD-induced fasting hyperglycemia or glucose intolerance, we next examined whether fasting insulin level, glucose-induced insulin secretion or insulin sensitivity were affected. There were no differences in fasting insulin levels (Figure 4A) and glucose-induced insulin secretion (Figure 4B). Insulin sensitivity assessed by ITT was also similar between groups (Figure 4C). To ascertain if Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 might play a role in peripheral insulin sensitivity on HFD, we examined the effects of their deficiency on glucose fluxes during a hyperinsulinic-eugylemic clamp (Figure 4D) in WT, Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice. The basal (fasting) glucose production was similar between groups. The glucose infusion rate (GIR) required to maintain euglycemia during the clamp and the rates of hepatic glucose production (HGP) and glucose disposal (Rd) were all similar between groups, indicating that hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity was not altered by deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both genes. There were no differences in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in perigonadal tissue; however, the Cx3cr1−/− mice showed reduced glucose uptake in gastrocnemius muscle (Figure S2). The latter may suggest a potential for selective muscle insulin resistance in Cx3cr1−/− mice, but this could be a spurious finding given the multiple testing and requires independent studies to replicate.

Figure 4. Deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both did not affect fasting insulin levels, glucose-induced insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity measured by ITT and hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in HFD-fed male mice.

A: Fasting plasma insulin levels were similar between groups (n=7 WT, 6 Ccr2−/−, 6 Cx3cr1−/−, 6 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). B: Glucose-induced insulin secretion (2g/kg glucose by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection) was similar between groups after 13 weeks of HFD. (n=5 WT, 5 Ccr2−/−, 5 Cx3cr1−/−, 5 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). C: ITT test showed similar insulin sensitivity between groups (n=11 WT, 9 Ccr2−/−, 9 Cx3cr1−/−, 14 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). D: Hyperinsulinic euglycemic clamp was performed in a representative subgroup of mice (n=6 WT, 5 Ccr2−/−, 6 Cx3cr1−/−, 6 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). Fasting hepatic glucose production (HGP) and HGP in response to insulin infusion during the clamp were similar between groups. Glucose infusion rate (GIR) required to maintain euglycemia and Rate of Glucose Disposal (Rd) were also not different. Data are mean±SEM. N.S., not significant.

Overall, our results suggested that the fasting blood glucose concentration, glucose tolerance, baseline and glucose-induced insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity were not affected by deletion of Ccr2 or Cx3cr1 or both during extended periods of HFD in male mice (Figures 2–4).

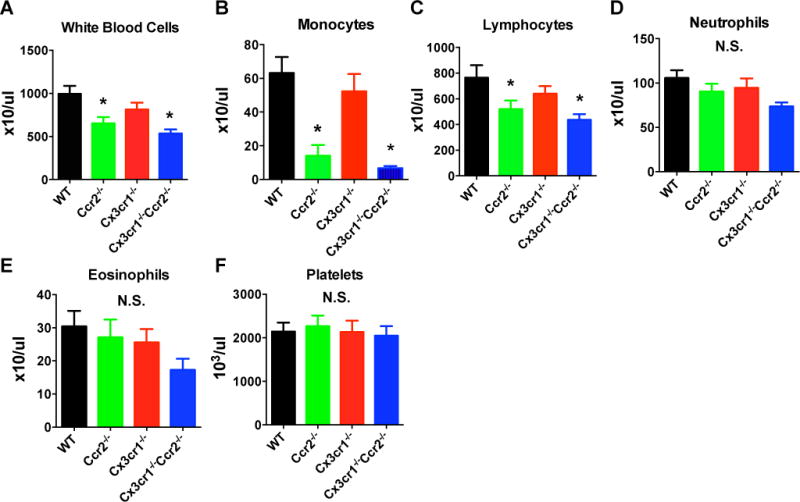

Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice but not Cx3cr1−/− mice have reduced circulating monocytes

Blood cell counts (Figure 5) showed expected reduction in total white blood cell and monocyte population in Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− male mice, but no significant difference was found between WT and Cx3cr1−/− mice as previously reported (17). The Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− double knockout mice also showed modest reduction in lymphocyte populations. Flow cytometry of blood was consistent showing lower CD115+ monocytes as a percentage of CD45+ leukocytes in Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice but not in Cx3cr1−/− mice (Figure S3).

Figure 5. Total blood levels of white blood cells and monocytes were reduced in Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− male mice, but not in Cx3cr1−/− male mice.

Blood counts with differential were performed after 15 weeks of HFD. The results showed lower numbers of total white blood cells (A) and monocytes (B) in Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice, but not in Cx3cr1−/− mice. Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice also had lower levels of lymphocytes (C), but the effects were less marked. There were no differences in the numbers of neutrophils, eosinophils and platelets between groups (D–F). Data are mean±SEM. *, P<0.05 vs. male WT mice; n=7 WT, 7 Ccr2−/−, 4 Cx3cr1−/−, 8 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−. N.S., not significant.

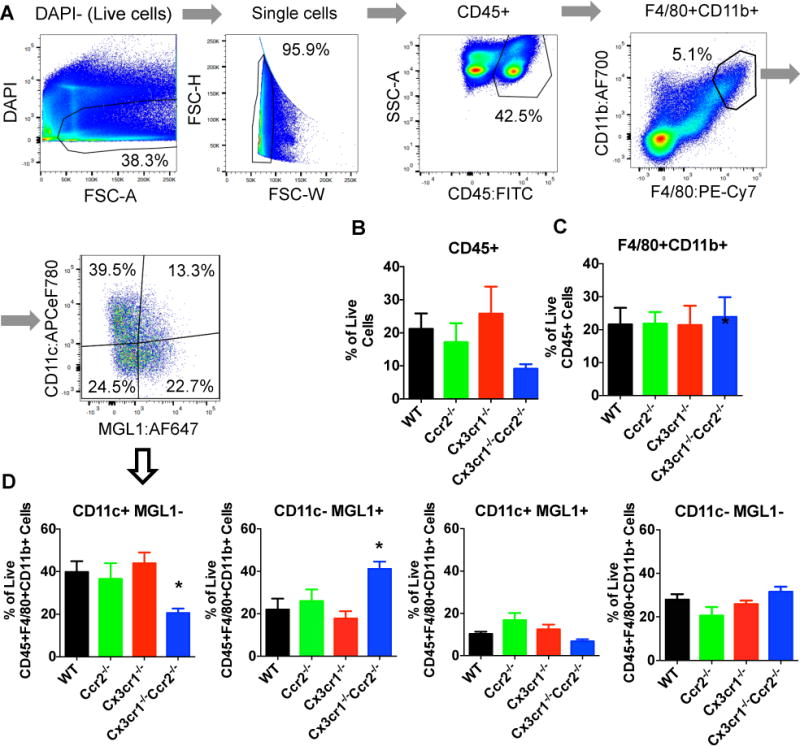

Double knockout of Cx3cr1 and Ccr2, but not single knockout of either gene, modulated the relative proportion of M1 to M2 macrophages in adipose of male mice

The gating strategies for adipose flow cytometry were shown in Figure 6A. The percentages of live and single CD45+ leukocytes in SVF of male mice epididymal adipose tissue were not statistically different between groups, though Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice showed a trend toward lower values (Figure 6B). Total F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages as a percentage of live CD45+ leukocytes were identical between groups (Figure 6C), suggesting that knockout of Ccr2 or Cx3cr1 or both did not specifically affect macrophage accumulation in visceral adipose tissue. However, CD11c+MGL1− M1-like macrophages as a percentage of live CD45+F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages were reduced, coincident with reciprocal increase of CD11c-MGL1+ M2-like macrophages, in Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice but not in Ccr2−/− or Cx3cr1−/− mice (Figure 6D). CD11c−MGL1− double negative, and CD11c+MGL1+ double positive macrophages were similar between groups. The results suggest that in males deficiency of both Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 may ameliorate adipose tissue inflammation during HFD feeding by modulating the relative proportion of M1 vs. M2 macrophages.

Figure 6. In male mice, double knockout of Cx3cr1 and Ccr2, but not their individual deletion, reduced M1-like but increased M2-like macrophages in epididymal adipose tissue.

A: Gating strategies for flow cytometric analysis of the stromal vascular fraction of epididymal adipose tissue was performed in male mice. B: CD45+ adipose leukocytes as a percentage of live single cells were not statistically different between groups, but trended lower in Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice vs. WT mice. C: F4/80+CD11b+ adipose macrophages as a percentage of live CD45+ cells were not different between groups. D: CD11c+MGL1− M1-like macrophages as a percentage of live CD45+F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages were lower, while CD11c−MGL1+ M2-like macrophages were higher in the Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice vs. WT mice. In contrast, a single knockout of Cx3cr1 or Ccr2 did not affect macrophage proportions in adipose. Data are mean±SEM of representative data from 9 WT, 8 Ccr2−/−, 9 Cx3cr1−/−, 8 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−. *, P<0.05 vs. male WT mice.

Despite the effects of double knockout of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 on the ratio of M1/M2 macrophages, the knockout showed no consistent effects on modulating expression of a handful of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes (Ccl2, Cx3cl1, Il1b, Il12a, Il6, Tnf, Il10, Tgfb1) in epididymal adipose tissue and in liver (Figure S4 and S5). We also explored whether knockout of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 affected systemic inflammation. Circulating levels of CCL2, but not CX3CL1 and CCL5, were increased by HFD feeding (Figure S6). Knockout of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 did not affect plasma CCL5 levels but did lead to an expected compensatory increase in plasma CCL2 and CX3CL1 levels respectively (Figure S6).

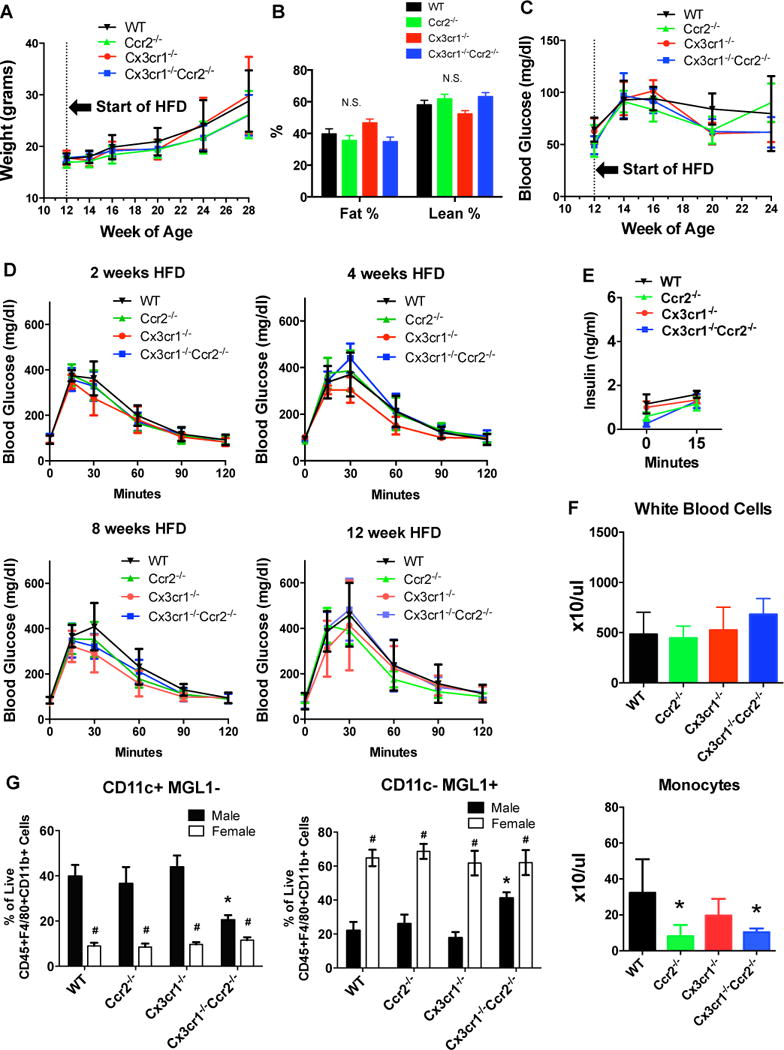

Female mice differ in their response to HFD and chemokine receptor deficiency

Sex differences in the metabolic impact of high-fat diet have been reported (23). To probe whether the role of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 in diet-induced obesity was similar in females and males, we examined the metabolic and inflammatory phenotypes in a cohort of female WT, Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice. Body weight (Figure 7A), body composition (Figure 7B), fasting hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance (Figure 7C–7D), and glucose-induced insulin secretion (Figure 7E) were similar between groups. Compared to HFD-fed male mice, however, female mice had lesser weight gain (e.g. at 16 weeks of HFD, body weight was 41.0±1.1g for male WT mice and 27.5±1.2g for female WT mice, P<0.001) and lower fasting glucose levels (e.g. at 12 weeks of HFD, fasting glucose level was 149±11 mg/dl for male WT mice and 79±11 mg/dl for female WT mice, P<0.001). As expected and similar to males, female Ccr2−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice also showed reduced blood monocyte levels (Figure 7F). Females showed generally lower percentage of M1-like macrophages, and higher percentage of M2-like macrophages compared to male mice of the same genotype (Figure 7G). In contrast to male Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice, female Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice did not demonstrate altered adipose macrophage distribution vs. female WT mice. These results confirm that, relative to males, female mice are protected from HFD-induced metabolic dysregulation and inflammation, and reveal that genetic deficiency of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 in female mice, does not attenuate further the more modest metabolic and inflammatory impact of HFD than that observed in males.

Figure 7. Effects of deficiency of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or both on metabolic and inflammatory phenotypes in female mice.

Female WT, Ccr2−/−, Cx3cr1−/− and Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− mice were fed a 45% HFD starting at 12-weeks of age (n=10 WT, 10 Ccr2−/−, 5 Cx3cr1−/−, 5 Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−). A: Body weight was measured every 2–4 week. B: Body composition was measured by NMR after 21 weeks of HFD. C and D: Fasting blood glucose and IPGTT were examined in female mice using the same protocols as in male mice. E: Glucose-induced insulin secretion was measured after 13 weeks of HFD after an overnight fast and was not different between groups. F: Blood count with differential was performed after 19 weeks of HFD. *, P<0.05 compared with female WT mice. G: Flow cytometric analysis of stromal vascular fraction of perigonadal adipose tissue was performed in female mice and data were compared with male mice. *, P<0.05 when comparing male WT mice with male mice of other genotypes; #, P<0.05 when comparing male and females mice of the same genotype. Data are mean±SEM. n=6 female WT, 6 female Ccr2−/−, 4 female Cx3cr1−/−, 5 female Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/−. N.S., not significant.

Discussion

This is the first study examining the combined impact of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 chemokine receptor deletion on HFD-induced obesity and related phenotypes in mice. Surprisingly, genetic deficiency of Ccr2 or Cx3cr1, or combined deletion of both, failed to attenuate 45% HFD-induced obesity, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in either male or female mice. As expected (14), knockout of Ccr2 lowered blood monocytes in both sexes, yet despite this, deficiency of Ccr2 alone did not alter the distribution of M1-like or M2-like macrophages in obese adipose tissue in our studies. Combined deficiency of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 in male mice reduced the proportion of M1-like to M2-like adipose macrophages, suggesting potential cooperative effects of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 on adipose macrophage phenotypes in males on HFD. Compared to males, females were relatively resistant to HFD-induced obesity and glucose intolerance as has been reported (23), and had lower percentage of M1-like and higher percentage of M2-like macrophages in perigonadal adipose tissue. In the context of this sex differences, dual deletion of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 in female mice had no apparent impact on adipose macrophage phenotypes.

Overall, our findings suggest that the apparent attenuation of adipose macrophage activation in the combined Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 deficiency does not translate to improved metabolic profile. This was likely due to the rather modest impact of combined Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 deficiency on systemic inflammation in our studies. The lack of association between altered polarization of adipose macrophages and adipose gene expression may be because whole adipose was used for the qRT-PCR analysis, potentially masking a modest effect on expression in adipose macrophages, which represent a minority portion of adipose SVF (Figure 6A). Future studies may specifically determine the gene expression profile of isolated adipose macrophages. In addition, examining circulating levels of a broad spectrum of cytokines and chemokines implicated in obesity (24, 25) may reveal further incremental insights. Nonetheless, our results cast doubt on a physiologically important role of these chemokine receptors and signaling pathways in diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders, at least in the specific rodent model contexts that we employed.

Our findings, however, raise further concerns for the reproducibility and design of rodent model studies of inflammatory pathways in obesity and its metabolic complications (26). Many factors may contribute to conflicting findings in these rodent studies including differences in diet, environment (e.g., ambient temperature and microbiome), the sex distribution, and genetic manipulation or background of mice. Dietary composition, in particular, is an important consideration (27). High-fat diets used in laboratory research can contain 32% to 60% calories from fat (28), with varying amounts and sources of protein and carbohydrate. From a nutritional perspective, a human diet of 60% calories from fat is extreme and not relevant to typical clinical settings (29). However, such diets are commonly used to induce obesity in rodents because the rapid weight gain allows researchers to screen effects of interventions after a shorter period of time (28). Previous studies have shown that global (5) or hematopoietic (16) Ccr2 deficiency ameliorated the metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue inflammation in mice with extended periods of 60% HFD feeding (D12492, Research Diets Inc.) for up to 20 to 24 weeks. By contrast, in our study using 45% HFD for up to 25 weeks, we did not observe metabolic and adipose inflammatory modulation with Ccr2 deficiency. It is possible that differences in diet – with protective effects of Ccr2 deletion being more apparent under more extreme metabolic stress – contributed to conflicting findings. Unmeasured environmental difference or distinct genetic targeting might also have contributed. Indeed, Weisberg et al. (5), used mice with deletion of Ccr2 by replacing all but the first 39 base pairs of the coding region (30) whereas in our study, the Ccr2−/− mice were generated by replacing the first 279 base pairs with a RFP transgene (18).

Conflicting findings also are apparent in studies examining the effects of Cx3cr1 deficiency on diet-induced metabolic traits in mice. In the current study using Cx3cr1−/− mice with knock-in of EGFP replacing the first 390 base pairs of the Cx3cr1 gene, we did not observe impact of Cx3cr1 deficiency on 45% HFD-induced metabolic phenotypes (19). This is in contrast to our prior report, using the same diet and mouse facility, but in a distinct Cx3cr1−/− mouse model generated by replacing the entire coding region with a neomycin-resistance gene, showed a modest protection from diet-induced insulin resistance (17). There have been several additional reports of inconsistent metabolic findings in HFD-fed Cx3cr1 deficient mice with different diet or distinct genetic background (31, 32, 33). Overall, disparate findings in these studies of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 deficient models suggest effects may be specific to the genetic strategies and that subtle metabolic and tissue inflammatory effects may be revealed or absent depending on the intensity and time-course of the high-fat diet.

Sex differences in the susceptibility to obesity and obesity-associated diseases are well established but poorly understood (23, 34, 35). Previous studies revealed that C57BL/6 male but not female mice (B&K Universal, Scanbur, Stockholm, Sweden) fed a 60% HFD developed visceral adipose inflammation, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance (23). In our study using a 45% HFD, female mice showed less weight gain and lower fasting glucose compared to male mice, coincident with lower percentage of M1-like macrophages and higher percentage of M2-like macrophage in adipose. These findings provide further evidence that female mice are protected from HFD-induced weight gain and metabolic disturbance and also reveal the lack the apparent impact of Ccr2, Cx3cr1 or dual Ccr2/Cx3cr1 deficiency in female mice. How these sex-differences and chemokine receptor genetic studies in rodent models translate to the human cardiometabolic setting has been unclear.

Yet, increasing human data are becoming available. Prior small human genetic studies have variably linked variation in the CCR2 and CX3CR1 genes to cardiometabolic traits (36, 37). Recently, however, our group interrogated very large genome-wide association, exome sequencing, and exome array genotyping datasets and found no association of genetic variation in these chemokine receptor genes with obesity, glucometabolic traits, or coronary artery disease (38, 39). In a South Asian cohort, we identified variants associated with myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes mellitus but these did not meet significance in much larger cohorts of European ancestry (39). In light of these human genetic data and our current rodent studies, it appears unlikely that functional genetic variation in CCR2 and CX3CR1 that modestly alters the balance of adipose macrophage activation has physiologically meaningful impact on HFD induced metabolic alterations including obesity and its metabolic complications. By inference, limited clinical utility is likely to be derived from therapeutic targeting CCR2 and CX3CR1 in obesity-associated metabolic diseases in humans.

Conclusion

In summary, a single knockout or double knockout of Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 did not attenuate weight gain, glucose intolerance or insulin resistance in response to HFD. Male Cx3cr1−/−Ccr2−/− double knockout mice, but not mice with single knockout of Ccr2 or Cx3cr1, had apparent modulation of adipose macrophage activation yet there was no impact on diet-induced metabolic derangements. Our study also underscores the known sex differences in obesity and metabolic responses to HFD and the need to perform studies that specifically address such sex differences in inflammation and metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance Questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Experimental evidence points toward the C-C motif chemokine receptor-2 (CCR2) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) as important modulators of inflammatory and metabolic phenotypes in diet-induced obesity in mice.

What does your study add?

Dual targeting of CCR2 and CX3CR1 on the metabolic and inflammatory consequences of obesity have not been examined.

CCR2 and CX3CR1 synergistically impact adipose tissue macrophage inflammatory phenotypes, but their joint deficiency does not influence metabolic effects of high fat diet-induced obesity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Israel F. Charo for providing the Ccr2−/−/Cx3cr1−/− mice (Ccr2rfp/rfp/Cx3cr1gfp/gfp)

Funding: This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-DK-090505 (to MPR) and the Penn Diabetes Research Center Mouse Phenotyping Core grant P30-DK-19525. HZ is supported by NIH grant K99-HL-130574. RS is supported by K23-DK-095913. MPR is also supported by R01-HL-111694, and R01-HL-113147, and K24-HL-107643. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author contributions: Conception and design: HZ SMO RSA MPR; data acquisition: HZ CCH SMO JS JC EL GL MG ASDT; data analysis: HZ CCH RSA MPR; manuscript writing: HZ MPR; editing of manuscript; RS JFF RSA; final approval of manuscript: HZ MPR.

References

- 1.Lumeng CN, Saltiel AR. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2111–2117. doi: 10.1172/JCI57132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brestoff JR, Artis D. Immune regulation of metabolic homeostasis in health and disease. Cell. 2015;161:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apovian CM, Bigornia S, Mott M, Meyers MR, Ulloor J, Gagua M, et al. Adipose macrophage infiltration is associated with insulin resistance and vascular endothelial dysfunction in obese subjects. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:1654–1659. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.170316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity. 2012;36:705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisberg SP, Hunter D, Huber R, Lemieux J, Slaymaker S, Vaddi K, et al. CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:115–124. doi: 10.1172/JCI24335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruun JM, Lihn AS, Pedersen SB, Richelsen B. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 release is higher in visceral than subcutaneous human adipose tissue (AT): implication of macrophages resident in the AT. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2005;90:2282–2289. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K, Mizuarai S, Araki H, Mashiko S, Ishihara A, Kanatani A, et al. Adiposity elevates plasma MCP-1 levels leading to the increased CD11b-positive monocytes in mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:46654–46660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah R, Hinkle CC, Ferguson JF, Mehta NN, Li M, Qu L, et al. Fractalkine is a novel human adipochemokine associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:1512–1518. doi: 10.2337/db10-0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong AM, Robinson LA, Steeber DA, Tedder TF, Yoshie O, Imai T, et al. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 mediate a novel mechanism of leukocyte capture, firm adhesion, and activation under physiologic flow. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:1413–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas G, Tacke R, Hedrick CC, Hanna RN. Nonclassical patrolling monocyte function in the vasculature. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2015;35:1306–1316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, et al. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science (New York, NY) 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annual review of immunology. 2008;26:421–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, et al. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Combadiere C, Potteaux S, Rodero M, Simon T, Pezard A, Esposito B, et al. Combined inhibition of CCL2, CX3CR1, and CCR5 abrogates Ly6C(hi) and Ly6C(lo) monocytosis and almost abolishes atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Circulation. 2008;117:1649–1657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.745091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez DA, Kennedy A, Orr JS, Anderson EK, Webb CD, Gerrald WK, et al. Aberrant accumulation of undifferentiated myeloid cells in the adipose tissue of CCR2-deficient mice delays improvements in insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2011;60:2820–2829. doi: 10.2337/db11-0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah R, O’Neill SM, Hinkle C, Caughey J, Stephan S, Lynch E, et al. Metabolic Effects of CX3CR1 Deficiency in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. PloS one. 2015;10:e0138317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saederup N, Cardona AE, Croft K, Mizutani M, Cotleur AC, Tsou CL, et al. Selective chemokine receptor usage by central nervous system myeloid cells in CCR2-red fluorescent protein knock-in mice. PloS one. 2010;5:e13693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, et al. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. Considerations in the design of hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in the conscious mouse. Diabetes. 2006;55:390–397. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGuinness OP, Ayala JE, Laughlin MR, Wasserman DH. NIH experiment in centralized mouse phenotyping: the Vanderbilt experience and recommendations for evaluating glucose homeostasis in the mouse. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2009;297:E849–855. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90996.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khor VK, Dhir R, Yin X, Ahima RS, Song WC. Estrogen sulfotransferase regulates body fat and glucose homeostasis in female mice. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;299:E657–664. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00707.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettersson US, Walden TB, Carlsson PO, Jansson L, Phillipson M. Female mice are protected against high-fat diet induced metabolic syndrome and increase the regulatory T cell population in adipose tissue. PloS one. 2012;7:e46057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke SJ, Karlstad MD, Regal KM, Sparer TE, Lu D, Elks CM, et al. CCL20 is elevated during obesity and differentially regulated by NF-kappaB subunits in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1849:637–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panchal SK, Brown L. Rodent models for metabolic syndrome research. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2011;2011:351982. doi: 10.1155/2011/351982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buettner R, Scholmerich J, Bollheimer LC. High-fat diets: modeling the metabolic disorders of human obesity in rodents. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2007;15:798–808. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston SL, Souter DM, Tolkamp BJ, Gordon IJ, Illius AW, Kyriazakis I, et al. Intake compensates for resting metabolic rate variation in female C57BL/6J mice fed high-fat diets. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2007;15:600–606. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dandona P, Ghanim H, Abuaysheh S, Green K, Batra M, Dhindsa S, et al. Decreased insulin secretion and incretin concentrations and increased glucagon concentrations after a high-fat meal when compared with a high-fruit and -fiber meal. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;308:E185–191. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00275.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boring L, Gosling J, Chensue SW, Kunkel SL, Farese RV, Jr, Broxmeyer HE, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100:2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris DL, Oatmen KE, Wang T, DelProposto JL, Lumeng CN. CX3CR1 deficiency does not influence trafficking of adipose tissue macrophages in mice with diet-induced obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2012;20:1189–1199. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polyak A, Ferenczi S, Denes A, Winkler Z, Kriszt R, Pinter-Kubler B, et al. The fractalkine/Cx3CR1 system is implicated in the development of metabolic visceral adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2014;38:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee YS, Morinaga H, Kim JJ, Lagakos W, Taylor S, Keshwani M, et al. The fractalkine/CX3CR1 system regulates beta cell function and insulin secretion. Cell. 2013;153:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauvais-Jarvis F. Sex differences in metabolic homeostasis, diabetes, and obesity. Biology of sex differences. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer K, Maley N, Mergian T, DelProposto J, Cho KW, Zamarron BF, et al. Differences in Hematopoietic Stem Cells Contribute to Sexually Dimorphic Inflammatory Responses to High Fat Diet-induced Obesity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290:13250–13262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.634568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDermott DH, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Merrell MN, Epstein N, et al. Association between polymorphism in the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 and coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Circulation research. 2001;89:401–407. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.095642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Zhang W, Li S, Song W, Chen J, Hui R. Genetic variants of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene and its receptor CCR2 and risk of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deloukas P, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Farrall M, Assimes TL, Thompson JR, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nature genetics. 2013;45:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golbus JR, Stitziel NO, Zhao W, Xue C, Farrall M, McPherson R, et al. Common and Rare Genetic Variation in CCR2, CCR5, or CX3CR1 and Risk of Atherosclerotic Coronary Heart Disease and Glucometabolic Traits. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2016;9:250–258. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.