Abstract

Background

The aim of this investigation is to compare the postoperative renal outcomes after on-pump beating- heart versus conventional cardioplegic arrest coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Methods

Between January 2010 and December 2012, 254 patients who underwent isolated CABG were enrolled. The primary outcome was postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) within 7 days [defined by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline] and loss of kidney function at 1 year (defined as > 20% loss in estimated glomerular filtration rate from baseline preoperative creatinine level).

Results

There was less AKI found for the on-pump beating-heart CABG (30.2% versus 46.3%; p = 0.010) group; with significant less stage I AKI (17.6% versus 29.5%; p = 0.035); a trend of less stage II AKI (4.4% versus 10.5%; p = 0.088) and no significant difference in stage III AKI (8.2% versus 6.3%; p = 0.587). The on-pump beating-heart group also had less patients who have lost their kidney function at 1 year (24.8% versus 41.2%; p = 0.021). Furthermore, multivariate analysis identified conventional arrest CABG is an independent risk factor for postoperative AKI and loss of kidney function at 1 year.

Conclusions

On-pump beating-heart CABG has superior short-term and mid-term renal outcomes than conventional cardioplegic arrest CABG.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Coronary artery bypass grafting, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects 12 to 50% of patients who undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). This statistical variation is due to different classification systems and study population.1-5 Postoperative AKI contributes to increased in-hospital mortality and decreased long-term survival, and it can also result in high medical expenditure and dependence on dialysis.6-8 Recent research has shown that even a minimal increase in serum creatinine level after CABG is independently associated with long-term mortality and cardiovascular outcomes.9 Other studies have also demonstrated an association between AKI and long-term kidney function impairment.10,11

Several clinical trials have compared off-pump CABG with on-pump CABG with regards to postoperative outcomes including renal function.12-16 However, the benefits of off-pump CABG are still controversial. The recent CORONARY trial demonstrated that off-pump CABG results in reduced rates of postoperative AKI, even though there was no significant difference in renal failure requiring dialysis.17 However, no previous study has evaluated the impact of on-pump beating-heart CABG and its postoperative renal outcomes. We hypothesized that this hybrid procedure of beating-heart surgery with the concomitant utilization of cardiopulmonary bypass to provide mechanical support for systemic circulation without cardioplegic arrest maybe beneficial for postoperative renal outcomes.18 The aim of this investigation was to compare the incidence rate of postoperative AKI and kidney function loss at one year after on-pump beating-heart (OPBH) versus conventional cardioplegic arrest (CCC) CABG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population

This post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected data was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital, and the need for individual consent was waived. Between January 2010 and December 2012, the medical records of 254 consecutive patients, including 159 with OPBH CABG and 95 with conventional CABG, in a tertiary referral hospital were reviewed. During the study period, 186 patients who received off-pump CABG were excluded. In order to appraise renal outcomes, the patients undergoing dialysis before surgery or who lacked perioperative creatinine data were also excluded.

Data collection and definitions

The clinical characteristics, demographic data, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score were extracted from our database. Baseline creatinine level was defined as the preoperative value obtained closest to the date of the operation (within 7 days before the operation). The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated using the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation as follows: 186 × (serum creatinine/88.4)-1.154 × (age)-0.203 × (0.742 if female). The primary outcome was postoperative AKI within 7 days. Based on the recently developed Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines for AKI, which reconcile the differences between the risk, injury, failure, loss of kidney function, and end-stage kidney disease (RIFLE) and acute kidney injury network (AKIN) criteria, AKI was defined as any of the following: increase in Scar ≥ 0.3 mg/dl within 48 hours, or increase in Scar ≥ 1.5 times the baseline value within 7 days. Finally, the patients were categorized into three different severities as defined by the KDIGO guidelines.19,20 The incidence and severity of AKI, and loss of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) > 20% at 1 year were compared between the patients who underwent OBPH CABG and conventional CABG.

Surgical technique

All surgeons at our institution are familiar with both techniques. The choice of OBPH or CCC CABG depended on the surgeon’s preference. Cardiopulmonary bypass was established in a similar manner in both cohorts with the use of continuous flow. In the conventional CABG group, we cooled the patients to a core temperature of 28-30 °C. Myocardial protection was obtained using 1 L of cold blood cardioplegiain a crystalloid cardioplegia: blood ratio of 4:1 delivered antegradely or retrogradely; to maintain cardiac arrest, this process was repeated with 300-500 cm3 of cold blood cardioplegia every 20-30 minutes. Proximal anastomosis of the vein graft to the aorta was performed after distal anastomosis of the coronary artery and during aortic cross-clamping. In the OPBH group, commercially available stabilizers were used, and intracoronary artery shunts were used in all anastomoses. No conversion of OPBH to conventional CABG was performed during the study period.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as mean and standard error unless otherwise stated. The primary endpoint was the comparison of renal outcomes between OPBH and on-pump conventional arrest CABG. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normal distribution for each variable. The Student t-test was used to compare the means of continuous variables and normally distributed data; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Categorical data were tested using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Furthermore, risk factors for AKI and a loss of > 20% eGFR at one year were assessed using univariate analysis. Age, gender and risk factors which were statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included into multivariate logistic regression analysis. Categorical data were tested using the χ2 test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population: OPBH versus conventional CABG

A total of 254 adult patients (mean age 63.7 ± 1.7 years; 206 males and 48 females) were investigated. All baseline patient characteristics are listed according to different surgical methods in Table 1. There were no significant differences in any of the characteristics including age, sex, underlying disease, essential laboratory data such as serum creatinine level, preoperative heart condition such as congestive heart failure functional class (CHF Fc), ejection fraction, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) usage, and recent myocardial infarction (MI) among the patients. The mean STS scores for the risk of mortality and renal failure were 6.6 ± 0.8% and 7.7 ± 0.8%, respectively. The observed 30-day mortality rate in this study was 5.5%.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients underwent on-pump beating-heart and on-pump conventional arrest coronary artery bypass surgery (expression as mean ± standard error).

| All patients (n = 254) | Beating (n = 159) | Arrest (n = 95) | p-value | |

| Preoperative demographic data | ||||

| Age (years) | 63.7 ± 0.7 | 64.0 ± 0.9 | 63.1 ± 1.1 | 0.525 |

| Gender, female (%) | 48 (18.9) | 29 (18.2) | 19 (20.0) | 0.729 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 130 (51.2) | 86 (54.1) | 44 (46.3) | 0.231 |

| Hypertension | 201 (79.1) | 126 (79.2) | 75 (78.9) | 0.955 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 19 (7.5) | 11 (6.9) | 8 (8.4) | 0.660 |

| Smoker | 153 (60.2) | 93 (58.5) | 60 (63.2) | 0.462 |

| Old stroke | 35 (13.8) | 20 (12.6) | 15 (15.8) | 0.473 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 24 (9.4) | 15 (9.4) | 9 (9.5) | 0.992 |

| ALT (units/L) | 44.1 ± 8.4 | 42.8 ± 11.5 | 46.5 ± 11.5 | 0.832 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.730 |

| Creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 19 (7.5) | 12 (7.5) | 7 (7.4) | 0.958 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 0.658 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 ± 0.1 | 12.8 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.2 | 0.571 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 22.6 ± 2.8 | 24.7 ± 4.1 | 20.0 ± 3.5 | 0.386 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 0.710 |

| Pre-operative heart condition | ||||

| CHF Fc III/IV (%) | 42 (16.5) | 25 (15.7) | 17 (17.9) | 0.652 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 52 ± 1 | 51 ± 1 | 53 ± 1 | 0.432 |

| EF < 35% | 44 (17.3) | 29 (18.2) | 15 (15.8) | 0.618 |

| Recent MI (%) | 120 (47.2) | 79 (49.7) | 41 (43.2) | 0.313 |

| Previous PCI (%) | 62 (24.4) | 42 (26.4) | 20 (21.1) | 0.336 |

| Ventilator support (%) | 27 (10.6) | 21 (13.2) | 6 (6.3) | 0.085 |

| Inotropic agent support (%) | 36 (14.2) | 25 (15.7) | 11 (11.6) | 0.359 |

| IABP (%) | 34 (13.4) | 23 (14.5) | 11 (11.6) | 0.513 |

| ECMO support (%) | 5 (2.0) | 5 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0.094 |

| Pre-operative scores | ||||

| STS-risk of mortality | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 0.255 |

| STS-renal failure | 7.7 ± 0.8 | 8.5 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 0.253 |

ALT, alanine transaminase; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF Fc, congestive heart failure functional class; ECMO, extracorporeal memebrane oxygenation; EF, ejection fraction; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; IABP, intraortic balloon pump; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Surgical data: OPBH versus conventional CABG

There were no significant differences in diseased coronary vessels, usage of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA), second arterial graft, or redo surgery between the two groups. Compared to the conventional arrest CABG group, more patients in the OPBH group had undergone emergent surgery (29.6% versus 14.7%; p = 0.007), had a shorter cardiopulmonary bypass time (110.1 ± 3.2 minutes versus 130.2 ± 5.5 minutes; p = 0.001), and had a higher minimal hemoglobin level during cardiopulmonary bypass (7.7 ± 0.1 g/dL versus 7.2 ± 0.1 g/dL; p = 0.007). Furthermore, fewer grafts were performed in the OPBH group than in the conventional arrest group (3.3 ± 0.1 versus 3.1 ± 0.1; p = 0.023). The OPBH procedure was technically more difficult, which may have caused incomplete revascularization. The detailed surgical information for the OPBH and conventional arrest groups are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Surgical data of different surgical methods (expression as mean ± standard error).

| All patients (n = 254) | Beating (n = 159) | Arrest (n = 95) | p-value | |

| Disease coronary vessels | ||||

| Left main (%) | 127 (50.0) | 80 (50.3) | 47 (49.5) | 0.897 |

| Triple (%) | 212 (83.5) | 131 (82.4) | 81 (85.3) | 0.551 |

| Double (%) | 41 (16.1) | 28 (17.6) | 13 (13.7) | 0.411 |

| Single (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.374 |

| Surgical detail | ||||

| Urgent or emergent operation (%) | 61 (24.0) | 47 (29.6) | 14 (14.7) | 0.007 |

| Redo operation (%) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2.1) | 0.558 |

| LIMA usage (%) | 234 (92.1) | 147 (92.5) | 87 (91.6) | 0.802 |

| Second arterial graft (%) | 69 (27.2) | 37 (23.3) | 32 (33.7) | 0.071 |

| Mean bypassed grafts | 3.1 ± 0.0 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 0.023 |

| Lowest Hb during CPB (g/dL) | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 0.007 |

| Aortic cross-clamping time (minutes) | - | 90.7 ± 3.4 | - | |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (minutes) | 110.1 ± 3.2 | 130.2 ± 5.5 | 0.001 |

CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; Hb, hemoglobin; LIMA, left internal mammary artery.

Postoperative outcomes: OPBH versus conventional CABG

Fourteen (5.5%) patients died within 30 days, with no statistical difference between the two groups (OPBH: 6.3% versus CCC: 4.2%; p = 0.579). Postoperative morbidity analysis including postoperative drainage amount, re-exploration for bleeding, stroke, and tracheostomy also showed similar results. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the duration of ventilator support, length of intensive care unit stay, and hospital stay between the two groups. Details postoperative mortalities and morbidities are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Postoperative outcomes of different surgical methods (expression as mean ± standard error).

| All patients (n = 254) | Beating (n = 159) | Arrest (n = 95) | p-value | |

| Postoperative outcomes | ||||

| Surgical mortality (%) | 14 (5.5) | 10 (6.3) | 4 (4.2) | 0.579 |

| Postoperative drainage amount (ml) | 793.4 ± 48.2 | 738.5 ± 62.6 | 881.1 ± 74.9 | 0.150 |

| Re-exploration for bleeding (%) | 8 (3.1) | 5 (3.1) | 3 (3.2) | 1.000 |

| Stroke (%) | 6 (2.4) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.415 |

| Tracheostomy (%) | 8 (3.1) | 6 (3.8) | 2 (2.1) | 0.714 |

| Ventilator duration (hours) | 41.9 ± 5.9 | 41.3 ± 8.5 | 42.9 ± 7.0 | 0.918 |

| ICU duration (days) | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 0.761 |

| Hospital stays (days) | 21.7 ± 1.6 | 21.7 ± 2.1 | 21.6 ± 2.7 | 0.967 |

| Postoperative renal outcome at seven days | ||||

| Postoperative acute kidney injury (%) | 92 (36.2) | 48 (30.2) | 44 (46.3) | 0.010 |

| New renal failure requiring dialysis (%) | 15 (5.9) | 11 (6.9) | 4 (4.2) | 0.425 |

| Renal outcome at one year | (n = 181) | (n = 113) | (n = 68) | |

| Post OP eGFR/Pre OP eGFR ratio | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.404 |

| > 20% loss in eGFR (%) | 56 (30.9) | 28 (24.8) | 28 (41.2) | 0.021 |

| New event of ESRD (%) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (4.4) | 0.366 |

EGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end stage renal disease; ICU, intensive care unit; OP, operative.

Renal outcomes

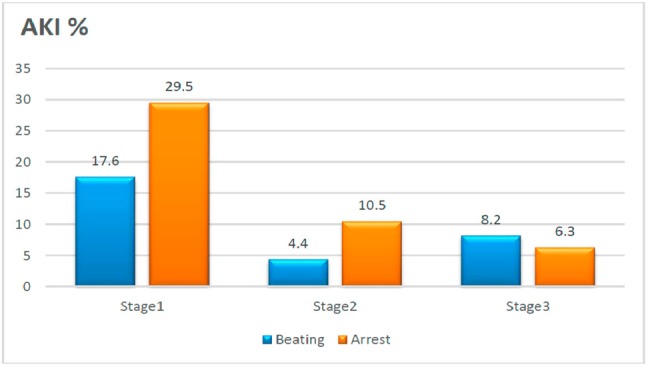

AKI of any severity occurred in 92 patients (36.2%) within 7 days, with stage 1 accounting for most of the cases (Figure 1). There was less AKI in the OPBH (30.2% versus 46.3%; p = 0.010) group, with significantly less stage I AKI (17.6% versus 29.5%; p = 0.035), a trend of less stage II AKI (4.4% versus 10.5%; p = 0.088), and no significant difference in stage III AKI (8.2% versus 6.3%; p = 0.587). The incidence rates of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy were also similar between the groups (6.9% and 4.2% for the OPBH and conventional arrest CABG groups, respectively; p = 0.425).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the stage of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) and the corresponding surgical method (p = 0.035 for stage 1, p = 0.088 for stage 2, and p = 0.587 for stage 3).

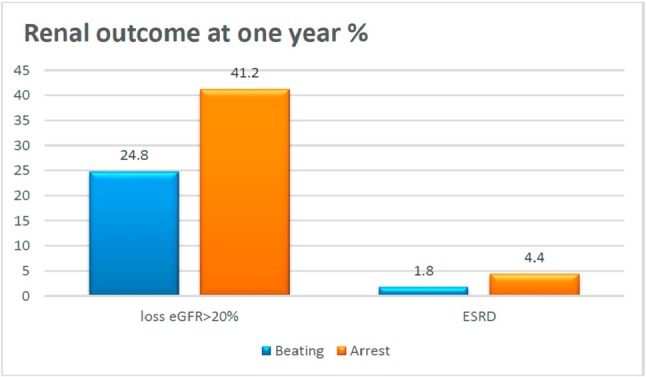

Figure 2 illustrates the comparisons of > 20% loss of eGFR and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) at one year for the different surgical methods. Fewer patients lost their kidney function at 1 year in the OPBH group (24.8% versus 41.2%; p = 0.021). However, there was no significant difference in new events of ESRD (1.8% versus 4.4%; p = 0.366) between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Comparison of loss of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥ 20% and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) at one year according to surgical method. p = 0.021 at loss eGFR ≥ 20%, p = 0.366 at ESRD.

Logistic regression analysis for AKI and loss of renal function at one year according to perioperative variables

Univariate analysis revealed that the predictors of postoperative AKI were conventional arrest CABG, advanced heart failure [NYHA (Fc) III/IV], longer cardiopulmonary bypass time, postoperative bleeding amount, renal insufficiency (creatinine > 2 mg/dl), and recent MI. However, multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that only conventional CABG (p = 0.024; odds ratio = 1.917) and longer bypass time (p = 0.035; odds ratio = 1.007) were significant risk factors. For predictors of loss of renal function at one year (loss 20% in eGFR), only conventional CABG (p = 0.039; odds ratio = 2.029) and recent MI (p = 0.002; odds ratio = 2.857)\demonstrated a significant impact in multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate analyses of risk factors for postoperative AKI and loss of eGFR > 20% at 1 year.

| Parameter | Beta coefficient | Standard error | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p |

| Risk factors for postoperative AKI | ||||

| Conventional arrest CABG | 0.651 | 0.288 | 1.917 (1.089-3.373) | 0.024 |

| CHF Fc III/IV | 0.456 | 0.370 | 1.578 (0.764-3.258) | 0.218 |

| Bypass time | 0.007 | 0.003 | 1.007 (1.001-1.012) | 0.035 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.542 | 0.285 | 1.720 (0.984-3.006) | 0.057 |

| Creatinine > 2 mg/dL | 0.317 | 0.520 | 1.373 (0.495-3.804) | 0.542 |

| Recent MI | 0.378 | 0.282 | 1.459 (0.839-2.537) | 0.181 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 0.740 | 0.535 | 2.095 (0.734-5.983) | 0.167 |

| Constant | -2.927 | 0.601 | ||

| Risk factors for loss in eGFR 20% at one year | ||||

| Conventional arrest CABG | 0.708 | 0.343 | 2.029 (1.036-3.974) | 0.039 |

| Recent MI | 1.050 | 0.345 | 2.857 (1.452-5.623) | 0.002 |

| Preoperative shock | 0.762 | 0.494 | 2.143 (0.814-5.644) | 0.123 |

| Constant | -2.426 | 0.557 | - | - |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHF Fc, congestive heart failure functional class; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MI, myocardial infarction.

DISCUSSIONS

In this study, we compared the renal outcomes between OPBH CABG with conventional arrest CABG among 254 patients. The incidence of all severities of AKI was 36.1% (defined according to the KDIGO guidelines). Reductions in postoperative AKI and loss of renal function at one year were found in the OPBH CABG group. Furthermore, multivariate analysis identified that conventional arrest CABG was an independent risk factor for postoperative AKI and loss of kidney function at 1 year.

The relatively higher incidence of postoperative AKI (36.1%) may be due to our high-risk population who had STS scores for the risk of morality and renal failure of 6.6% and 7.7%, respectively. It could also be because we excluded patients with off-pump CABG, which is usually performed electively in stable patients. Furthermore, different study definition criteria may also have had an impact on the incidence of AKI. The recently developed KDIGO guidelines for AKI attempt to consolidate the differences between the RIFLE and AKIN criteria.16,21 The guidelines have been validated in studies with patients who underwent cardiac surgery, with the incidence of all severities of AKI ranging from 24-42%, which is compatible with our results.22,23

The development of AKI is associated with unfavorable outcomes and high mortality in patients undergoing isolated CABG. The mechanisms of AKI after cardiac surgery are multifactorial and can include ischemia-reperfusion, cytokine release, hemolysis, oxidase stress, and nephrotoxic exposure. Convincing evidence now exists demonstrating that off-pump CABG surgery reduces the risk of mild to moderate AKI.24 However, this finding is not universal.25 The recent CORONARY trial subgroup analysis demonstrated a reduced risk of postoperative AKI, however, it failed to show better preserved kidney function at 1 year.26 A possible reason is that the risk of hemodynamic instability during surgery, with the possibility of incomplete and suboptimal quality of revascularization due to inherent technical difficulties, may negate the benefits of avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass.25

No previous study has evaluated the impact of OPBH CABG on postoperative renal outcomes. We hypothesized that this hybrid procedure of beating-heart surgery with the concomitant utilization of cardiopulmonary bypass to provide mechanical support to the systemic circulation without cardioplegic arrest maybe beneficial for postoperative renal outcomes.18 This procedure provides optimal operative exposure with adequate drainage of the heart, stable hemodynamics during anastomosis, and allows the surgeon to feel comfortable with performing complete revascularization even with poor quality coronary vessels. No conversion procedures to conventional CABG, a risk factor for a poor prognosis, were performed during our study. Compared to conventional CABG, OPBH CABG can avoid cardiac arrest and ischemia-reperfusion injury, which are related to the release of free radicals and have been demonstrated to be risk factors for AKI.27 In addition, pulsatile flow is provided by the patient’s cardiac output when using a beating heart technique. Organ damage has been demonstrated to be attenuated in pulsatile cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) compared with non-pulsatile CPB.28 Therefore, the OPBH group had pulsatile CPB, which may have improved the clinical renal outcomes. Furthermore, the OPBH CABG group had a shorter CPB time than the conventional CABG group. The reduction in CPB time resulted from the avoidance of systemic hypothermia and cardiac arrest due to a reduced time of systemic temperature rewarming, recovery from myocardial stunning, and weaning from CPB. Rewarming on CPB has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for postoperative AKI,29,30 and a longer CPB time has been reported to contribute to the incidence of AKI. Finally, there was a clear relationship between the lowest hemoglobin level during CPB and postoperative AKI, possibly because of a decrease in oxygen delivery due to reduced oxygen transport capacity of the blood as well as a disturbed microcirculation.31,32 The lowest hemoglobin level during CPB was higher in the OPBH CABG group (7.7 ± 0.1 mg/dl for OPBH, 7.2 ± 0.1 mg/dl for CCC-CABG, p = 0.007) as no cardioplegia solution was used, which has been shown to contribute to hemodilution. However, because incomplete revascularization may cause long-term inferior results, surgeons should consider the benefits of renal function and the disadvantages of a lower bypass graft number in OPBH-CABG.

Study limitations

Despite the favorable results, there are several important limitations to this study. First, our study is limited by its post-hoc analysis nature and all of its inherent limitations. Although all of the surgeons at our institute are familiar with both surgical techniques, for most patients, the surgeons tended to perform the procedures they were most familiar with, and as such selection bias could not be eliminated by our retrospective design. Additional randomized trials are warranted, to overcome this limitation. Second, this series has a relatively small number of cases with heterogeneity of urgent and elective surgery. Third, this study was conducted at a single tertiary care medical center in Asia, and regional and ethnic differences should be considered, and the results may not be directly extrapolated to other patient populations. Finally, since the etiology of AKI is often multifactorial, postoperative care that was not involved in this study may have caused inaccuracies in the results.

CONCLUSIONS

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first assessment of postoperative AKI and kidney function at one year after OPBH versus conventional cardioplegic arrest CABG. The principle findings of the current study are as follows. First, OPBH CABG reduced the risk of postoperative AKI, and contributed to less mild and moderate AKI compared to conventional CABG. Second, OPBH CABG also resulted in better preserved kidney function than conventional CABG at one year. Finally, multivariate analysis identified conventional CABG and longer CPB time as independent risk factors for postoperative AKI. Recent MI and conventional CABG were shown to be independent risk factors for the loss of renal function at one year. In conclusion, OPBH CABG had superior short- and mid-term renal outcomes than conventional arrest CABG.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from the grant CORPG3C0182 Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

FUNDING

The work was supported by grants from the grant CORPG3C0182 Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. The funders had no role in study design, data collecon and analysis, decision to publish, or preparaon of the manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

SWC and CHC contributed to the conception of the study. SWC, CHC and FCT did the design of the work. YC, PJL and CTH did the acquisition of the study. SWC and CHC did the analysis and interpretation of data for the work, literature search, and drafting the work. CCL and YYN did the revising and approving the final version of the article for submission. VCCW, DYC and FCT contributed to critically revising the article for important intellectual content.

COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This post-hoc analysis of a prospectively collected database was approved by the institution’s research bureau (IRB), where individual consents were waived.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gallagher S, Jones DA, Lovell MJ, et al. The impact of acute kidney injury on midterm outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a matched propensity score analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:989–995. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryden L, Ahnve S, Bell M, et al. Acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting and long-term risk of myocardial infarction and death. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosner MH, Okusa MD. Acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:19–32. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YC, Tsai FC, Chang CH, et al. Prognosis of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: the impact of acute kidney injury on mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reents W, Hilker M, Borgermann J, et al. Acute kidney injury after on-pump or off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:9–14, discussion 14-5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y, et al. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen TH, Chang CH, Lin CY, et al. Acute kidney injury biomarkers for patients in a coronary care unit: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin CY, Tsai FC, Tian YC, et al. Evaluation of outcome scoring systems for patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liotta M, Olsson D, Sartipy U, et al. Minimal changes in postoperative creatinine values and early and late mortality and cardiovascular events after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pannu N, Hemmelgarn B. The acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease continuum: comment on "The magnitude of acute serum creatinine increase after cardiac surgery and the risk of chronic kidney disease, progression of kidney disease, and death". Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:233–234. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012;81:442–448. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellke FW, DiMaio JM, Caplan LR, et al. Comparing on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: numerous studies but few conclusions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association council on cardiovascular surgery and anesthesia in collaboration with the interdisciplinary working group on quality of care and outcomes research. Circulation. 2005;111:2858–2864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.165030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puskas JD, Williams WH, Mahoney EM, et al. Off-pump vs conventional coronary artery bypass grafting: early and 1-year graft patency, cost, and quality-of-life outcomes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1841–1849. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathoe HM, van Dijk D, Jansen EW, et al. A comparison of on-pump and off-pump coronary bypass surgery in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:394–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Straka Z, Widimsky P, Jirasek K, et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary surgery: final results from a prospective randomized study PRAGUE-4. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai YT, Lai CH, Loh SH, et al. Assessment of the risk factors and outcomes for postoperative atrial fibrillation patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2015;31:436–443. doi: 10.6515/ACS20150609A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, et al. Off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 30 days. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1489–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai YT, Lin FY, Lai CH, et al. On-pump beating-heart coronary artery bypass provides efficacious short- and long-term outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2059–2065. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:649–672. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okusa MD, Davenport A. Reading between the (guide)lines--the KDIGO practice guideline on acute kidney injury in the individual patient. Kidney Int. 2014;85:39–48. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.References. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2013;3:136–150. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastin AJ, Ostermann M, Slack AJ, et al. Acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery according to Risk/Injury/Failure/Loss/End-stage, Acute Kidney Injury Network, and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes classifications. J Crit Care. 2013;28:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machado MN, Nakazone MA, Maia LN. Prognostic value of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery according to kidney disease: improving global outcomes definition and staging (KDIGO) criteria. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seabra VF, Alobaidi S, Balk EM, et al. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery and acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1734–1744. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02800310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwann NM, Horrow JC, Strong MD, 3rd, et al. Does off-pump coronary artery bypass reduce the incidence of clinically evident renal dysfunction after multivessel myocardial revascularization? Anesth Analg. 2004;99:959–964, table of contents. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000132978.32215.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg AX, Devereaux PJ, Yusuf S, et al. Kidney function after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2191–2198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Billings FTt, Ball SK, Roberts LJ, 2nd, et al. Postoperative acute kidney injury is associated with hemoglobinemia and an enhanced oxidative stress response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1480–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salameh A, Kuhne L, Grassl M, et al. Protective effects of pulsatile flow during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boodhwani M, Rubens FD, Wozny D, et al. Effects of mild hypothermia and rewarming on renal function after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newland RF, Baker RA, Mazzone AL, et al. Rewarming temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass and acute kidney injury: a multicenter analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karkouti K, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN, et al. Hemodilution during cardiopulmonary bypass is an independent risk factor for acute renal failure in adult cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermeer H, Teerenstra S, de Sevaux RG, et al. The effect of hemodilution during normothermic cardiac surgery on renal physiology and function: a review. Perfusion. 2008;23:329–338. doi: 10.1177/0267659109105398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.