Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is increasingly viewed as a disease of synapses. Loss of synapses correlates better with cognitive decline than amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the hallmark neuropathological lesions of AD. Soluble forms of amyloid-β (Aβ) have emerged as mediators of synapse dysfunction. Aβ binds to, accumulates, and aggregates in synapses. However, the anatomical and neurotransmitter specificity of Aβ and the amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) in AD remain poorly understood. In addition, the relative roles of Aβ and AβPP in the development of AD, at pre- versus post-synaptic compartments and axons versus dendrites, respectively, remain unclear. Here we use immunogold electron microscopy and confocal microscopy to provide evidence for heterogeneity in the localization of Aβ/AβPP. We demonstrate that Aβ binds to a subset of synapses in cultured neurons, with preferential binding to glutamatergic compared to GABAergic neurons. We also highlight the challenge of defining pre- versus post-synaptic localization of this binding by confocal microscopy. Further, endogenous Aβ42 accumulates in both glutamatergic and GABAergic AβPP/PS1 transgenic primary neurons, but at varying levels. Moreover, upon knock-out of presenilin 1 or inhibition of γ-secretase AβPP C-terminal fragments accumulate both pre- and post-synaptically; however earlier pre-synaptically, consistent with a higher rate of AβPP processing in axons. A better understanding of the synaptic and anatomical selectivity of Aβ/AβPP in AD can be important for the development of more effective new therapies for this major disease of aging.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-beta, gamma-secretase, synapse

INTRODUCTION

Synapses are a unique characteristic of nerve cells and are increasingly seen as critical sites of pathogenesis in neurodegenerative diseases of aging. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), it has long been known that loss of synapses is a better brain correlate of cognitive decline than the number of amyloid plaques or neurofibrillary tangles [1, 2], the two neuropathological hallmark lesions. The high metabolic demands of the brain relate to the large amount of energy consumed by synaptic function. It has been hypothesized that this high-energy consumption at synapses could lead to their age-related vulnerability from reactive oxidant species [3, 4]. Further, synaptic activity stimulates amyloid-β (Aβ) generation and secretion [5], as well as degradation [6]. The observation that the anatomy of amyloid plaque pathology in the brain resembles metabolic activity in the default network has led to a hypothesis that synaptic activity via stimulated generation and secretion of Aβ may drive Aβ accumulation and thereby AD pathogenesis [7]. Several other findings point to synapses as critical mediators of the disease. Aβ in brain accumulates and aggregates particularly in synaptic terminals with Aβ pathogenesis, which occurs even prior to plaques [8, 9]. Aβ selectively binds to synapses when added to cultured neurons [10]. Further, Aβ oligomers in synaptosomes were shown to be increased in early AD but not in brains of cognitively normal individuals who showed amyloid pathology [11].

In contrast to several other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, the anatomic and neurotransmitter specificity of synaptic damage in AD remains poorly understood. Neurochemical and neuropathological studies on postmortem brain have provided some insights into the selective vulnerability in AD with evidence for preferential loss of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and basal forebrain cholinergic neurons [12–15]. Region-specific accumulation of intraneuronal Aβ42 was noted particularly in AD vulnerable neurons, such as layer II neurons of entorhinal cortex (ERC), CA1 pyramidal neurons of hippocampus and basal forebrain cholinergic neurons, which appeared to increase with age, but then decreased with severity of dementia and plaque deposition [16]. More recently, intracellular Aβ42 immunoreactivity was more carefully described in the cholinergic neuronal population in the basal forebrain and shown to be stronger compared to in the pyramidal neurons of the superior temporal and insular cortices [17]. Moreover, it is well known that tangle pathology in the hippocampal formation initiates in a set of projection neurons in layer II of ERC that then degenerate early in the disease [18, 19]. Early accumulation of Aβ42 in Reelin-positive neurons of ERC layer II was recently reported [20]. While these glutamatergic Reelin-positive ERC layer II neurons are destined for early tangle pathology and loss in AD, initial plaques in the hippocampus develop in their terminal fields in the outer molecular layer of the dentate, providing an explanation for the apparent anatomical disconnect between amyloid and tau pathologies. Studies on the subcellular distribution of intracellular Aβ accumulation in brain have emphasized post-synaptic accumulation and aggregation of Aβ, although marked pre-synaptic localization was also reported [8]. When it comes to extracellular Aβ, it was shown that added exogenous oligomeric Aβ1 - 42 appears to bind particularly to the post-synapse, where it overlapped with the post-synaptic marker PSD-95 [10], although this Aβ did not bind equally to all neurons. Further evidence for such selectivity of Aβ came from a report showing that not all neurons are equally sensitive to Aβ-induced synapse damage [21].

It also remains unclear whether amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) trafficking and generation of Aβ, occurs more in pre- compared to post-synaptic terminals [22, 23]. AβPP is known to be transported down both axons and dendrites and the proteases that cleave AβPP to generate Aβ have been localized to both pre- and post-synaptic sites. One recent report in primary neurons showed that one genetic risk factor for late onset AD, Bin1, promoted axonal Aβ generation in endosomes, while another genetic risk factor, CD2AP, promoted Aβ generation in dendrites [24]. Evidence also supports pre-synaptic Aβ generation in certain anatomical pathways such as the mossy fibers of the hippocampus, given accumulation of BACE1 and Aβ at these sites [25]. More than 150 familial AD-causing mutations in presenilin 1 (PS1), critical for the final cleavage to generate Aβ, have been identified and approximately 10 additional mutations have been found in the homologous gene PS2 (http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations). Conditional knock-out of PS1 was reported to lead to accumulation of AβPP CTFs to pre-synaptic sites of CA1 in hippocampus [26]. Interestingly, a recent report highlighted that PS1 and PS2 appear to differ in their trafficking and relative cleavage of AβPP in axons compared to dendrites [27]. Thus, current evidence supports that at anatomical, neuron-type and subcellular levels, there are differences in AβPP processing, Aβ generation and AD-related pathogenesis.

Here we set out to provide new evidence pertaining to the anatomic and synaptic selectivity of AβPP processing and Aβ accumulation. We also aim to highlight work that will be necessary to better define the subcellular site of Aβ involvement within neurons as well as the selective vulnerability of certain neurons in AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Primary neuronal cultures were generated from B6.Cg-Tg(AβPP swe,PSEN1dE9) 85Dbo/Mmjax mice (AβPP/PS1) AD transgenic (tg) and wild-type (wt) mouse embryos. The AβPP sequence in AβPP/PS1 encodes a chimeric mouse/human AβPP (Mo/Hu AβPP 695swe) that was humanized by modifying three amino acids, and introducing the Swedish AD mutation. The PS1 sequence encodes human presenilin 1 lacking exon 9 (dE9) that models AD-associated mutations in PS1. Both AβPPswe and PS1 are independently controlled by the prion protein promoter. Primary neuronal cultures were prepared from cortices including hippocampi of embryonic day 15 embryos as previously described [9]. In brief, E15 brain tissue was dissociated by trypsinization and trituration in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco). Dissociated neurons were cultured on poly-D-lysine (Sigma) coated plates or glass coverslips (Bellco Glass Inc.) and were maintained in neurobasal medium (Gibco), B27 supplement (Gibco), glutamine (Invitrogen) and antibiotics (ThermoScientific). All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee of Lund University.

Mice

PS1 cKO; AβPP Tg mice were generated as described [26].

Cell immunofluorescence

Cultured neurons at 12 and 19 DIV or N2a cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS with 0.12 M sucrose for 20 min, permeabilized and blocked in PBS containing 2% normal goat serum (NGS), 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% saponin at room temperature for 1 h, and then immunolabeled in 2% NGS in PBS overnight at 4°C. After appropriate washing, coverslips were mounted with SlowfadeGold (Invitrogen). For PSD-95 labeling cells were fixed 10 min in 4% PFA in PBS with 0.12 M sucrose followed by 5 min in ice-cold methanol in –20°C. Immunofluorescence was examined with epifluorescent microscope (Olympus IX70) (Fig. 1A only) or by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Leica TCS SP8). In multiple label experiments, channels were imaged sequentially to avoid bleed-through. Images were taken with Leica Confocal Software and analyzed with ImageJ or Imaris x64 8.3. Colocalization analysis was performed with Imaris with automatic thresholding based on point spread function width. For ImageJ analysis of localization of γ-secretase cleaved AβPP, thresholds were set by automatic thresholding by default on confocal images in the MAP2 or tau-1 channel. The mean intensity of the 369 channel was subsequently measured in the pixels that were above threshold in the MAP2 or tau-1 channel, respectively.

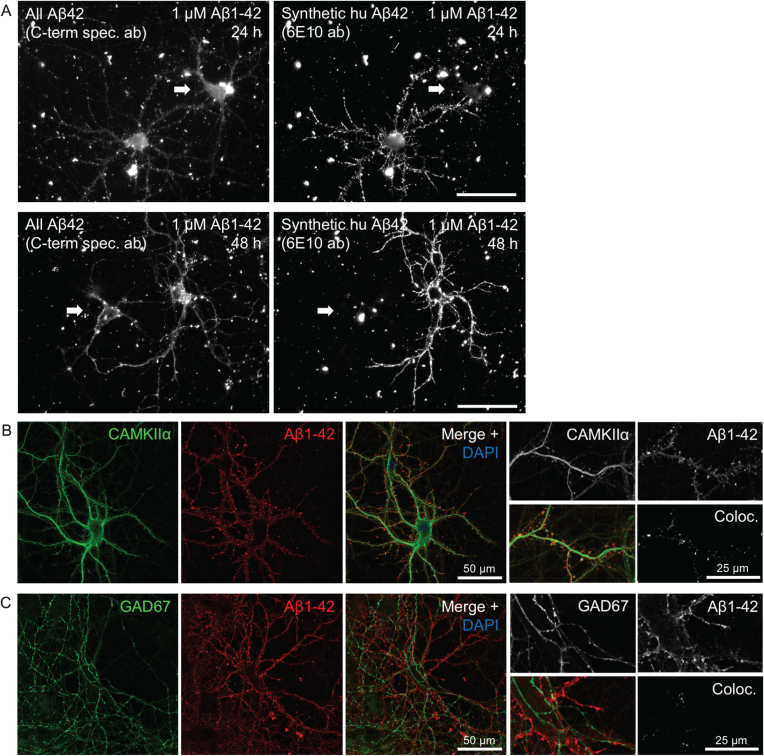

Fig.1.

Heterogeneity in Aβ1 - 42 binding and internalization. A) Only certain neurons in culture accumulate synthetic Aβ1 - 42 in a punctate pattern along the processes. Epifluorescent imaging of wt primary mouse neurons treated with 1 μM human Aβ1 - 42 for 24 h or 48 h. Labeling with a C-terminal specific Aβx - 42 antibody (left panels) showing both endogenous mouse Aβ42 and the added human synthetic Aβ1 - 42, displays two large neurons in each of these images. However, the exogenously added human Aβ1 - 42, recognized by antibody 6E10 (right panels), accumulates predominantly only in one of the two neurons, including their processes. Note the brighter labeling with the high affinity antibody 6E10 of only one of the two neurons in the right image panels. Scale bars 50 μm. B-C) Accumulation of exogenously added Aβ1 - 42 for 30 min is more pronounced in excitatory CamKII-positive compared to inhibitory GAD67-positive neurons. B) Aβ1 - 42 accumulation in some but not all, and not exclusively in, neurons labeled with CamKIIα. Higher magnification images (right) with Aβ1 - 42 in CamKIIα-positive synaptic terminals that appear more consistent with dendritic spines. C) Aβ1 - 42 was not seen accumulating in any GAD67-positive neurons.

Aβ

Aβ1 - 42 peptides (Tocris) or Aβ1 - 42 HiLytetrademark Fluor 555 labeled peptides (Aβ555) (AnaSpec) were reconstituted in DMSO to 250 μM, sonicated for 10 min and followed by 15 min of centrifugation at 12k rpm before adding the supernatant to the culture media in depicted final concentrations.

Antibodies and reagents

The following antibodies were used: 369 [28] IF 1:500; 6E10 (BioLegend, previously Covance SIG-39320) IF: 1:500; 12F4 (BioLegend, previously Covance SIG-39142) for immunofluorescence (IF) 1:250; Amyloidβ (1–42) (IBL, 18582); Amyloidβ (1–42) (Invitrogen, 700254) IF 1:1000; CAMKIIα (Millipore, 05–532) IF 1:500; DAPI (Sigma, D9542) IF 1:2000; drebrin (Abcam, ab11068) IF 1:1000; GAD67 (Millipore, MAB5406) IF 1:1000; MAP2 (Sigma, M4403) IF 1:1000; PSD-95 (Millipore, MAB1596) IF 1:200; somatostatin (Millipore, MAB354) IF 1:200; synapsin I (Sigma, S1939) IF 1:500; synaptophysin (Merck Millipore, MAB5258) IF 1:1000; tau-1 (Chemicon, MAB3420) IF 1:500; secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor-488, –546, –647 (IF 1:500; Invitrogen). γ-secretase inhibitor N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT; Calbiochem) was diluted in culture medium to 250 nM.

Colocalization analysis

Colocalization analysis was performed using Imaris software. The colocalization channel displays the intensity of colocalized voxels as the square root of the product of the intensities of the original channels, hence the brightest pixels in the colocalization channel represent the pixels with the highest colocalization. Under conditions of proportional codistribution, the points of the scatter plot cluster around a straight line. However, lack of colocalization is reflected by distribution of points onto two separate groups, each showing varying levels of one probe with little or no signal from the other probe. Quantification of colocalization was done with automatic thresholding and was reported as percentage of colocalized material above threshold. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) is based on an algorithm developed by Costes and Lockett at the National Institute of Health, NCI/SAIC [29]. PCC values range from 1 for two images whose fluorescence intensities are perfectly linearly related, to –1 for two images whose fluorescence intensities are perfectly, but inversely, related to one another. Values near zero reflect distributions that are uncorrelated with one another. Because PCC subtracts the mean intensity from the intensity of each pixel value, it is independent of signal levels and background. Thus, PCC can be measured without any form of preprocessing, making it relatively safe from user bias. Manders’ Colocalization Coefficients (MCC) is the fraction of the total probe fluorescence of one protein that colocalizes with the fluorescence of a second protein. MCC strictly measures co-occurrence independent of signal proportionality. It is necessary to first eliminate the background and this is done automatically in Imaris by the method developed by Costes [29].

Immunogold electron microscopy

Paraffin embedded brain sections (10 μm) of PS1cKO; AβPP Tg mice were deparaffinized, alcohol-dehydrated, and free-floating sections were incubated with 369 antibody (AβPP C-terminal epitope) by the immunogold-silver procedure with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 1 nm gold particles (Amersham Biosciences, Arlington, IL) in 1.01% gelatin and 0.08% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Transmission electron microscopy was performed on a Philips CM10 electron microscope. Immunogold electron microscopic analysis were performed as previously described [8].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with PRISM 6 software (Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) by using unpaired t-test. Data are expressed as mean±SD. Differences were considered significant at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

RESULTS

Selective binding and internalization of exogenously added Aβ

Binding and uptake of synthetic human Aβ1 - 42 (huAβ1 - 42) added to primary mouse neurons in culture is remarkably heterogeneous for different neurons. As an example, two neurons side-by-side can show completely different abilities to accumulate exogenous huAβ1 - 42 added for 24 h and 48 h to the culture medium (Fig. 1A). While the whole dendritic tree is labeled by huAβ1 - 42 in a punctate pattern in one neuron, an adjacent neuron (white arrow) is completely devoid of huAβ1 - 42 along its processes. In some cases, neurons negative for huAβ1 - 42 in their dendrites, do however show strong huAβ1 - 42-signal in their cell bodies (Fig. 1A). In general, huAβ1 - 42 accumulation in the cell body increases with time, with more neurons showing large amounts of huAβ1 - 42 in their cell bodies at 48 h compared to 24 h.

Neurons can broadly be classified as either excitatory or inhibitory. We therefore first asked whether Aβ binds preferentially to certain types of neurons, based on whether they express excitatory or inhibitory markers. We first confirmed that primary neurons incubated with fluorescently tagged Aβ1 - 42 (Aβ555) for 30 min also preferentially accumulated only in select neurons consistent with the results obtained with untagged human Aβ shown in Fig. 1A. Immunofluorescent labeling of CAMKIIα, which recognizes the majority of glutamatergic neurons, shows that some but not all of the Aβ555-positive neurons co-label for CAMKIIα. However, not all CAMKIIα-positive cells have strong Aβ555-labeling. Figure 1B shows a CAMKIIα-positive cell with prominent Aβ555-labeling along its processes, with marked labeling also of terminals, which appear consistent with dendritic spines (Fig. 1B higher magnification). In contrast, no overlap was observed upon labeling Aβ555-treated cells with GAD67, a marker for GABAergic neurons, despite GAD67-positive processes often being very close or intertwined with Aβ555-positive processes (Fig. 1C).

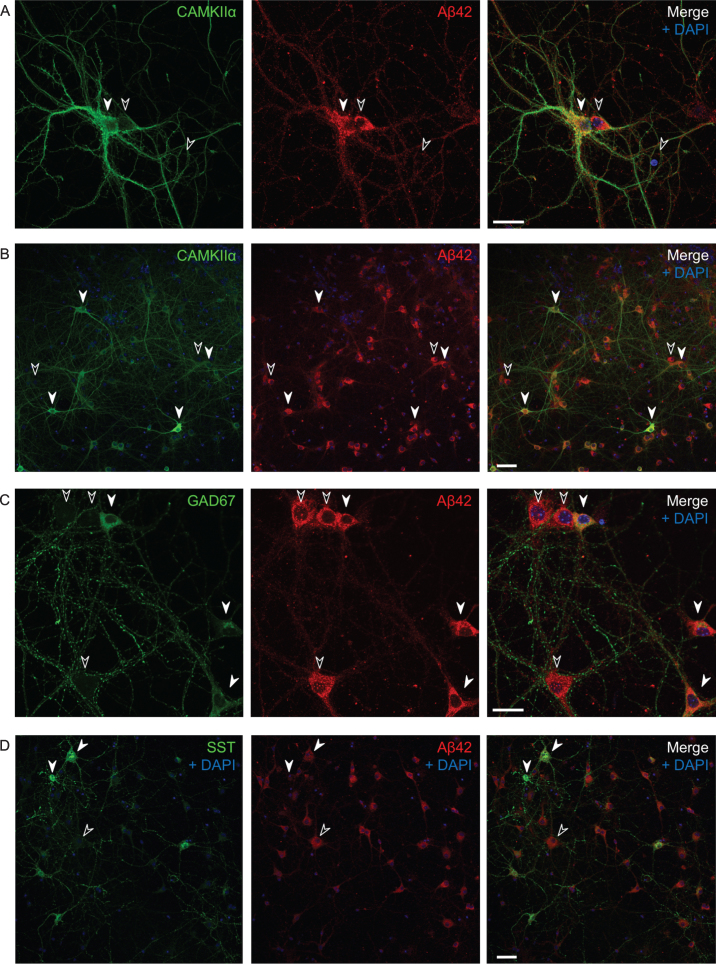

Untreated transgenic AβPP/PS1 primary neurons in culture also display varying levels of endogenous Aβ42 (Fig. 2), even though they all overexpress AβPPswe under the prion protein promoter. We therefore asked whether the excitatory or inhibitory type of individual neurons could affect the intracellular Aβ42 levels. All CAMKIIα-positive cells (white filled arrows) have high levels of Aβ42, with 27% of all Aβ42 positive cells being CAMKIIα-positive. However so do many, but not all, CAMKIIα-negative cells as well (black arrows) (Fig. 2A, B). Many GAD67-positive neurons show similar high levels of Aβ42 to CAMKIIα-positive neurons; in total about 26% of all Aβ42 positive cells were GAD67-positive (Fig. 2C). There was also variability in labeling of endogenous Aβ42 in somatostatin positive inhibitory neurons, which represent a subgroup of the GAD67-positive GABAergic neurons, with some showing low levels of Aβ42, with 2% of all Aβ42 positive cells being somatostatin positive and 44% of all somatostatin positive cells being positive for Aβ42 (Fig. 2D).

Fig.2.

Varying endogenous Aβ42 levels in AβPP/PS1 primary neurons in culture. Immunofluorescent labeling of AβPP/PS1 primary neurons. A, B) All CAMKIIα-positive cells (white filled arrows) have high levels of Aβ1 - 42; however, so do many, but not all, CAMKIIα-negative cells as well (black arrows). Also note that the two side by side neurons in (A) with varying levels of CAMKIIα (the positive to the left and the negative to the right) have comparable high levels of Aβ1 - 42. C, D) Many GAD67-positive neurons show high levels of Aβ42 (C), however, some somatostatin positive cells have lower levels of Aβ42 (D). Scale bars 25 μm (A and C) and 50 μm (B and D).

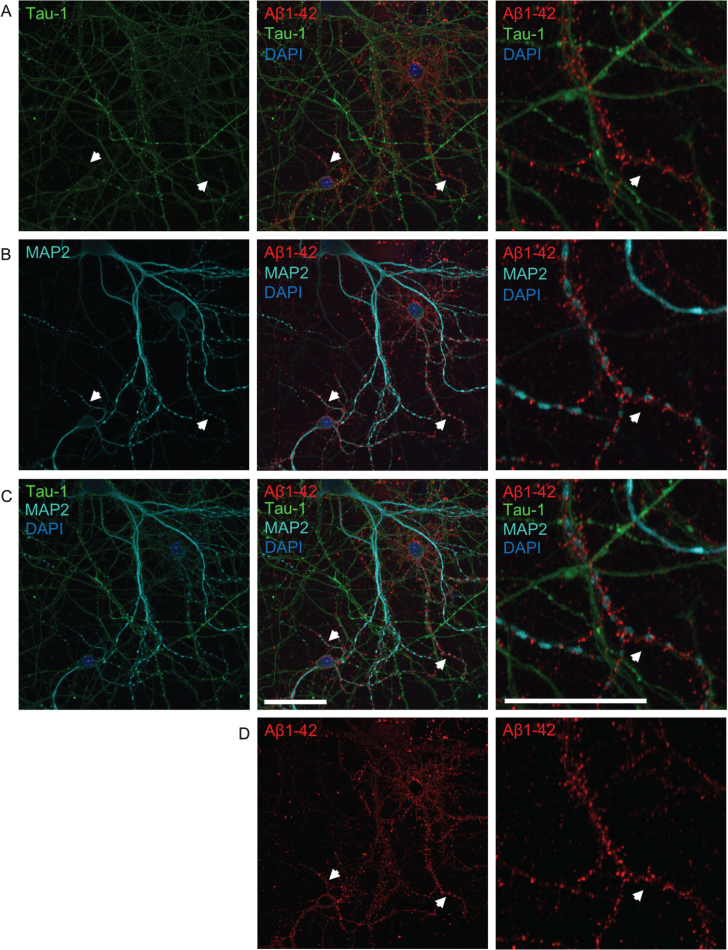

The pattern of Aβ accumulation in neurons is more consistent with dendritic labeling

To determine whether added human Aβ1 - 42 preferentially localizes to axons or dendrites, primary neurons were treated with 0.5 μM fluorescently-tagged Aβ1 - 42 (Aβ555) for 30 min and subsequently labeled with tau-1 and MAP2 antibodies to label axons and dendrites, respectively (Fig. 3). Aβ555 did not clearly co-localize well with either tau-1 or MAP2, which could be due to these proteins not extending fully into synaptic terminals. However, the overall pattern of Aβ labeling appeared more similar to that observed with dendritic MAP2 rather than axonal tau-1 labeling. It appeared that Aβ1 - 42 was present near to MAP2, or between MAP2 and tau-1 positive processes, suggesting accumulation at synaptic terminals and in particular dendritic spines.

Fig.3.

The pattern of Aβ accumulation in neurons is more consistent with dendritic labeling. A-D) Double-labeling with axonal tau-1 (A) and dendritic MAP2 (B) markers of primary neurons treated with 0.5 μM of fluorescently tagged Aβ1 - 42 (Aβ555) for 30 min. All images show the same field of view. Merged images of both tau-1, MAP2, Aβ1 - 42, and DAPI are shown in row C. The panel to the far right show higher magnification images of the middle panel. The pattern of Aβ labeling (shown separately in row D) is more consistent with that of dendritic MAP2 than tau-1 labeling. White arrows denote MAP2-positive dendrites accumulating Aβ555, which are not positive for tau-1. High magnification images (right) show tau-1-positive axons devoid of Aβ555. Scale bars 50 μm.

Aβ binds and accumulates at pre- and post-synaptic sites

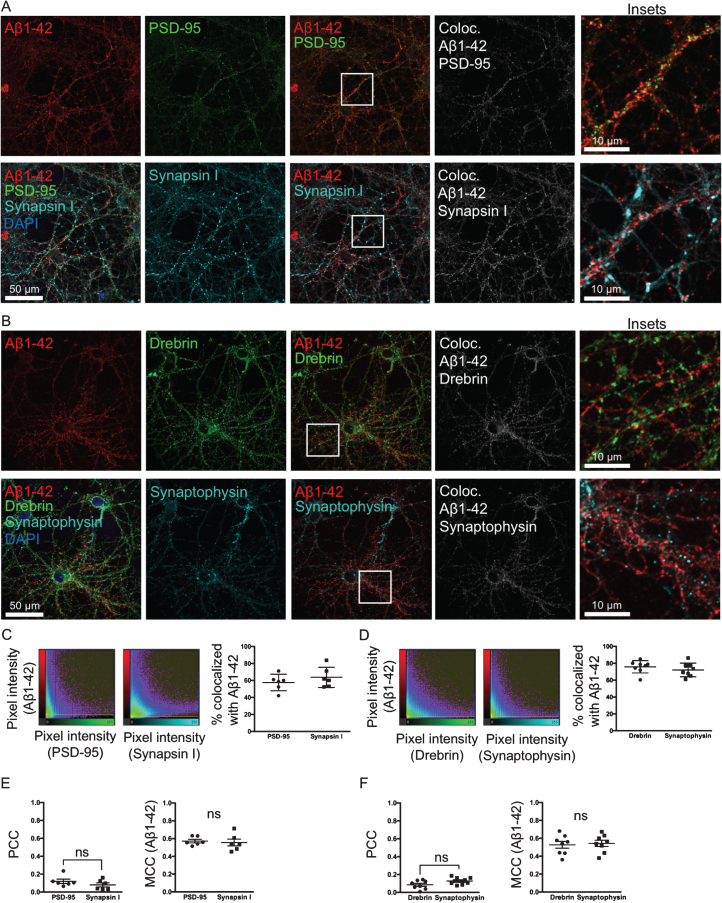

To test if Aβ1 - 42 is accumulating at synapses and whether it has a preference to the pre- or post-synaptic side, neurons were treated with Aβ555 for 30 min and labeled with two sets of pre- and post-synaptic markers, respectively: synapsin I and PSD-95 (Fig. 4A) or synaptophysin and drebrin (Fig. 4B). Aβ555 was co-labeled with one pre- and one post-synaptic marker on the same coverslip. Two different sets of pre-and post-synaptic markers were used, since the intensity and prevalence of a specific marker could potentially influence the colocalization analysis. In the colocalization images (Fig. 4A, B, right panel) the brightest pixels in the colocalization channel represent the pixels with the highest colocalization. The scatter plots (Fig. 4C, D) show the intensity of the Aβ1 - 42 channel plotted against the intensity of the respective pre- or post-synaptic channel for each pixel. Quantification of colocalization revealed that there is no significant difference in the percentage of material above threshold colocalized with Aβ555 between pre- and post-synaptic markers (Fig. 4C, D). PCC values between PSD-95 and synapsin I, and drebrin and synaptophysin, respectively, are not significantly changed (Fig. 4E, F). MCC values of Aβ1 - 42 are also not significantly changed between pre- and post-synaptic markers (Fig. 4E, F). Taken together, these results with two different sets of pre- and post-synaptic markers support that Aβ555 does not have a clear-cut preference for either the pre- or post-synaptic site.

Fig.4.

Aβ binds and accumulates at both pre- and post-synaptic sites. A, B) Double-labeling with two different pre-synaptic and post-synaptic markers synapsin I and PSD-95 (A) and synaptophysin and drebrin (B), respectively, of primary neurons treated with 0.5 μM of fluorescently tagged Aβ1 - 42 for 30 min. In the colocalization channel (right panel) the amount of colocalization is represented as such as the brighter the pixels, the higher the colocalization at that particular pixel. Scale bars 50 μm. C, D) The scatter plots show the intensity of the Aβ1 - 42 channel plotted against the intensity of the respective pre- or post-synaptic channel for each pixel. Quantification shows no significant difference in the percentage of colocalization above threshold between Aβ555 and pre- or post-synaptic markers. E, F) Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) values between PSD-95 and synapsin I, and drebrin and synaptophysin, respectively, are not significantly different. Manders’ Colocalization Coefficients (MCC) values for Aβ1 - 42 are also not significantly different between pre- and post-synaptic markers.

γ-secretase inhibition leads to earlier AβPP CTF accumulation at pre- than post-synaptic sites

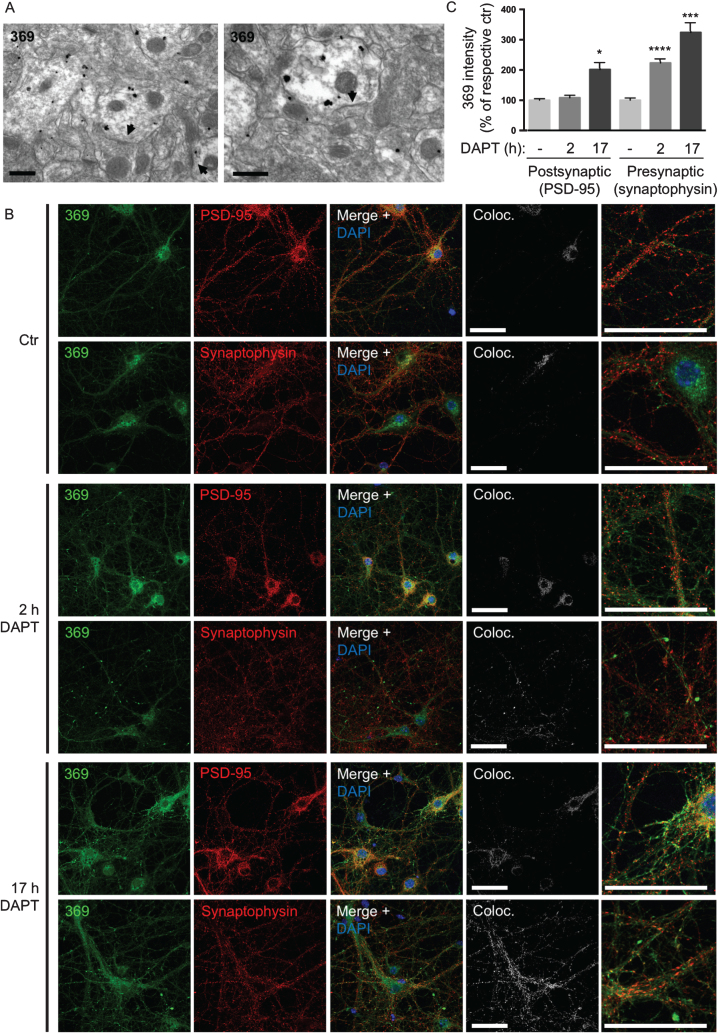

The complex subcellular localization and anatomy in the brain of AβPP processing is further evident with the anatomically and pre- versus post-synaptic selective accumulation of AβPP CTFs with γ-secretase inhibition or absence of PS1. Accumulation of AβPP CTFs in pre-synaptic compartments in the CA1 region of hippocampus was previously reported in conditional PS1 knock-out mice over-expressing AβPP (cKO; AβPP Tg mice) [26]. However, there is an anatomy to this AβPP CTF accumulation, since in the CA3 region of hippocampus AβPP CTFs mainly accumulate in post- rather than pre-synaptic compartments in these PS1 cKO; AβPP Tg mice (Fig. 5A). This shows that AβPP CTF accumulation due to lack of PS1 activity can occur both at the pre- and post-synaptic sites. To further explore this selective accumulation of CTF, we next used immunofluorescent labeling of AβPP/PS1 cortical, including hippocampal, primary neurons treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Of note, 17 h of DAPT treatment revealed AβPP CTF-accumulation with the C-terminal specific AβPP antibody 369 in both pre- and post-synaptic compartments as labeled with synaptophysin and PSD-95, respectively. However, at early time points AβPP CTFs upon DAPT treatment were evident only in pre-synaptic compartments. Specifically, after 2 h with DAPT there was a marked increase of AβPP CTFs in pre-synaptic compartments of treated compared to untreated neurons (223% of untreated control, p < 0.0001). After 17 h of DAPT treatment, AβPP CTFs were further increased in pre-synaptic compartments (324% of untreated control, p = 0.0001) and were now also evident in post-synaptic compartments (202% of untreated control, p = 0.02) (Fig. 5B, C). Further, labeling with markers for axons and dendrites indicated that AβPP CTFs accumulate in a pattern more consistent with axons in neurons treated with DAPT for 17 h (Supplementary Figure 2). Taken together these data support the conclusion that γ-secretase cleavage of AβPP, as measured by AβPP CTF-accumulation after γ-secretase inhibition, occurs earlier and/or to a larger extent in pre-synaptic compartments compared to post-synaptic compartments in cortical primary neurons.

Fig.5.

γ-secretase inhibition leads to earlier AβPP CTF accumulation at pre- than post-synaptic sites. A) In the CA3 region of hippocampus AβPP CTFs are mainly accumulating in post-synaptic compartments in PS1 cKO; AβPP Tg mice. Arrowheads denote post-synaptic densities. Scale bars 500 nm. B) Immunofluorescent labeling of AβPP/PS1 primary cortical neurons treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. AβPP CTF-accumulation is seen by C-terminal specific AβPP antibody 369 in both axons and dendrites after 17 h. However, with only 2 h of DAPT treatment, AβPP CTF-accumulation is evident only in pre-synaptic compartments. Scale bars 50 μm. C) Quantification of the intensity of antibody 369 labeling in post-synaptic compared to pre-synaptic compartments with DAPT-treatment indicates a relatively greater increase in pre-synapses, which is also evident earlier (at 2 h). Thresholds were set by automatic thresholding by default on confocal images in the MAP2 or tau-1 channel. The mean intensity of the antibody 369 channel was subsequently measured in the pixels that were above threshold in the MAP2 or tau-1 channel respectively. Values are presented as percentage of respective untreated control.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we discuss and further explore the more complex anatomy in brain and subcellular localization in neurons of Aβ and AβPP. Specifically, we show that exogenous Aβ1 - 42 accumulates in a punctate pattern along processes in a subset of CamKII-positive neurons but not in GAD67-positive neurons. We also demonstrate that exogenous Aβ1 - 42 does not clearly have a selective preference to either the pre- or post-synaptic side in cultured neurons. However, the overall pattern of exogenous Aβ1 - 42 accumulation in neurons is more consistent with dendritic labeling. Finally, we show with EM that γ-secretase inhibition leads to AβPP CTF accumulation at either the pre- or post-synaptic site depending on the anatomical localization in the hippocampus.

Amyloid deposition in the AD brain during the progression of the disease generally follows a similar pattern [30, 31], although variants occur such as the visual variant of AD [32]. It is possible that the specific vulnerability of certain brain areas and neurons in the AD brain are attributed to a preference of Aβ to accumulate in and/or bind to specific types of neurons. In fact, laser capture micro-dissection of individual neurons pooled from human brains showed that CA1 pyramidal neurons show much higher levels of endogenous Aβ42 compared to cerebellar Purkinje neurons [33]. Moreover, it was also shown that less Aβ binds to cerebellar compared to cortical synaptosomes [34]. We show that added human Aβ1 - 42 only accumulates in a subset of neurons in culture initially in a punctate pattern along their processes. This corroborates a previous study where Aβ diffusible oligomers (ADDLs) were shown to only bind at most half of neurons in hippocampal culture [10].

We demonstrate that accumulation of exogenously added Aβ1 - 42 occurs in certain, but not all, excitatory CamKII-positive neurons. We did not find any such accumulation in processes of inhibitory GAD67-positive neurons, supporting previous studies [10, 34]. Many factors may play a role in the affinity of Aβ binding and uptake in different types of neurons. Aβ has been proposed to interact with numerous different putative receptors, including among many others the PrPC receptor, metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5), a7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, immunoglobulin G Fcγ receptor II-b (FcγRIIb), mouse paired immunoglobulin- like receptor B (PirB), leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor (LilrB2) and Ephrin-like B receptor 2 (EphB2) [35–40]. In addition, AβPP has been shown to be important in the binding [42], toxicity [42, 43] and synapse altering effects of Aβ [6].

Overall, the pattern of Aβ accumulation in neurons treated with exogenous Aβ1 - 42 appears to be more consistent with dendritic labeling compared to axonal. However, as dendrites are thicker than axons, the greater surface area might give the impression of more Aβ in dendrites, no matter whether it is due to “unspecific” binding and/or uptake via the plasma membrane or via a more regulated mechanism via one or several specific target molecules. Moreover, using two different sets of pre-and post-synaptic markers, we found no selective preference of exogenous Aβ42 to either the pre- or post-synaptic side in cultured neurons. In contrast to our study, Lacor et al. [10] found that ADDLs colocalized with PSD-95. It is important to note that, colocalization analysis of Aβ with the pre- or post-synaptic site is very much dependent on the particular pre- or post-synaptic marker chosen to represent the synaptic sites. It is also likely that the concentration and conformation of Aβ will have an impact on the precise spatial targeting of added Aβ to synapses. Corroborating our results, a recent study showed endogenous non-fibrillar oligomeric Aβ within a subset of both pre- and post-synaptic sites in AβPP/PS1 mouse brains (labeled with synaptophysin and PSD-95, respectively) by transmission electron microscopy and array tomography [44]. It has been suggested that Aβ might have differential effects on the pre- and post-synaptic sides and that this effect depends on the concentration of Aβ [45]. Within a physiological range, small increases in Aβ might primarily facilitate pre-synaptic functions, resulting in synaptic potentiation [46, 47]. However, at abnormally high levels, Aβ could enhance LTD-related mechanisms, resulting in post-synaptic depression and loss of dendritic spines [48, 49].

As well as being endocytosed from the extracellular compartment, Aβ is also produced within neurons after γ-secretase cleavage of AβPP CTFs. Frykman et al. [50] reported the presence of active γ-secretase in preparations of synaptic vesicles and pre-synaptic membranes of rat brain. Sannerud et al. [27] reported that PS2 was exclusively present in the somatodendritic compartments, while PS1 localized to both axons and dendrites. Here we show by immuno-gold EM that AβPP CTF accumulation, due to lack of γ-secretase cleavage, occurs mainly in post-synaptic compartments in the CA3 region of hippocampus in PS1 cKO; AβPP Tg mice, while a previous report focusing on CA1 hippocampus described pre-synaptic accumulation [26]. This suggests an anatomical difference in the pre- versus post-synaptic γ-secretase activity in the brain. As the axons of CA3 neurons terminate in the CA1 region, a possible explanation for our results could be that CA3 neurons have particularly high γ-secretase cleavage of AβPP. This would in PS1 cKO; AβPP Tg mice leads to accumulation of AβPP CTFs both in the axon terminals of the CA3 neurons that terminate in pre-synaptic compartments in CA1 and in the dendrites of CA3 neurons in post-synaptic compartments of CA3. We also show by short term (2 h) treatment of chemical γ-secretase inhibitor that AβPP CTFs first and/or to a larger extent accumulate in pre-synaptic compartments in cortical neurons. However, after longer time points of DAPT treatment (17 h), AβPP CTFs are also evident in post-synaptic compartments. This suggests that either (1) only a small fraction of neurons accumulates AβPP CTFs in their post-synaptic compartments which is initially drowned out by most neurons not showing this, (2) a longer treatment duration being necessary to impact post-synaptic AβPP CTFs, and/or that AβPP CTFs first accumulate in pre-synaptic compartments that then only with time are transported to post-synaptic compartments. Another possible explanation of the preferential buildup of AβPP CTFs in the pre-synaptic compartment with γ-secretase inhibition could be faster degradation of AβPP CTFs in the post-synaptic compartment compared to the pre-synaptic compartment. AβPP CTFs have been shown to be degraded by the lysosome and since lysosomes are only found in the cell body of the neuron and not in the axon or dendrite, it appears less likely that the AβPP CTFs are degraded in either the axon or the dendrites. An additional possibility is that retrograde transport of AβPP CTF-containing multivesicular bodies to the cell body for degradation might be slower in axons compared to dendrites. However, vesicular trafficking of AβPP bearing a C-terminal tag typically appears more rapid in axons than dendrites [6].

AD is a complex disease of aging that is only gradually becoming better understood. The precise role of the Aβ peptide, which has been linked by pathological, genetic and biological lines of evidence to the disease, remains to be understood. Increasing evidence supports that like in other neurodegenerative diseases where synapses are sites of attack, the misfolding proteins linked to AD, Aβ and tau, also target synapses in this disease [8, 51]. How fundamental processes of aging make synapses vulnerable sites requires further work, although the wear and tear of synaptic activity and resulting oxidative, inflammatory, vascular and other stressors likely drive the vulnerabilities of synapses in age-related proteinopathies [52, 53].

Here we underscore the challenges in clearly differentiating Aβ binding to pre- compared to post-synaptic compartments and highlight anatomical differences in accumulation of AβPP metabolites. Synapse loss is considered the best pathological correlate of cognitive deficits in human AD [2]. Aβ accumulates at synapses and is associated with synaptic pathology [9] and leads to loss of synaptic markers such as PSD-95, GluR1 and synaptophysin [54]. Hence a better understanding of the subcellular site of Aβ involvement within neurons in AD will be important to understand the selective vulnerability and anatomical specificity of AD.

Supplementary Material

Gray level images of Fig. 1B, C. Accumulation of exogenously added Aβ1-42 is more pronounced in (A) excitatory CamKII-positive compared to (B) inhibitory GAD67-positive neurons.

γ-secretase inhibition leads to greater AβPP CTF accumulation in axons compared dendrites in cortical primary neurons. Immunofluorescent labeling of AβPP/PS1 primary cortical neurons treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. AβPP CTF-accumulation, as seen by C-terminal specific AβPP antibody 369, is increased in both tau-1 positive axons and MAP2 positive dendrites after 17 h DAPT treatment compared to control. However, the increase in AβPP CTF labeling after 17 h DAPT treatment is greater in axons compared to dendrites. Scale bars 50 μm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Carlos Saura and Jie Shen for their generation of the PS1cKO. This study was supported by MultiPark, the Swedish Research Council and NIH grant R01-AG027140.

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/17-0262r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170262.

REFERENCES

- [1]. DeKosky ST, Scheff SW (1990) Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: Correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol 27, 457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Hansen LA, Katzman R (1991) Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: Synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 30, 572–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Rajmohan R, Reddy PH (2016) Amyloid-beta and phosphorylated tauaccumulations cause abnormalities at synapses of Alzheimer’sdisease neurons. J Alzheimers Dis 57, 975–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Li F, Calingasan NY, Yu F, Mauck WM, Toidze M, Almeida CG, Takahashi RH, Carlson GA, Flint Beal M, Lin MT, Gouras GK (2004) Increased plaque burden in brains of APP mutant MnSOD heterozygous knockout mice. J Neurochem 89, 1308–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R (2003) APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37, 925–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Tampellini D, Rahman N, Gallo EF, Huang Z, Dumont M, Capetillo-Zarate E, Ma T, Zheng R, Lu B, Nanus DM, Lin MT, Gouras GK (2009) Synaptic activity reduces intraneuronal Abeta, promotes APP transport to synapses, and protects against Abeta-related synaptic alterations. J Neurosci 29, 9704–9713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, Sheline YI, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Morris JC, Mintun MA (2005) Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J Neurosci 25, 7709–7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Takahashi RH, Milner TA, Li F, Nam EE, Edgar MA, Yamaguchi H, Beal MF, Xu H, Greengard P, Gouras GK (2002) Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. Am J Pathol 161, 1869–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Takahashi RH, Almeida C, Kearney PF, Yu F, Lin MT, Milner TA, Gouras GK (2004) Oligomerization of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid within processes and synapses of cultured neurons and brain. J Neurosci 24, 3592–3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, Lambert MP, Velasco PT, Bigio EH, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL (2004) Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer’s-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci 24, 10191–10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Bilousova T, Miller CA, Poon WW, Vinters HV, Corrada M, Kawas C, Hayden EY, Teplow DB, Glabe C, Albay R 3rd, Cole GM, Teng E, Gylys KH (2016) Synaptic amyloid-β oligomers precede p-Tau and differentiate high pathology control cases. Am J Pathol 186, 185–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Davies P, Maloney AJ (1976) Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2, 1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Styren SD, Beckett L, Wisniewski S, Bennett DA, Cochran EJ, Kordower JH, Mufson EJ (2002) Upregulation of choline acetyltransferase activity in hippocampus and frontal cortex of elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 2, 145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Perry EK, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Perry RH, Crow TJ, Cross AJ, Dockray GJ, Dimaline R, Arregui A (1981) Neurochemical activitiesin human temporal lobe related to aging and Alzheimer-typechanges. Neurobiol Aging 2, 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Mesulam M (2004) The cholinergic lesion of Alzheimer’s disease: Pivotal factor or side show? Learn Mem 11, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Gouras GK, Tsai J, Naslund J, Vincent B, Edgar M, Checler F, Greenfield JP, Haroutunian V, Buxbaum JD, Xu H, Greengard P, Relkin NR (2000) Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in humanbrain. Am J Pathol 156, 15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Baker-Nigh A, Vahedi S, Davis EG, Weintraub S, Bigio EH, Klein WL, Geula C (2015) Neuronal amyloid-β accumulation within cholinergic basal forebrain in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138, 1722–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Braak H, Braak E (1995) Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-relatedneurofibrillary changes.271-278; discussion. Neurobiol Aging 16, 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Gómez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW Jr, Morris JC, Growdon JH, Hyman BT (1996) Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 16, 4491–4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Kobro-Flatmoen A, Nagelhus A, Witter MP (2016) Reelin-immunoreactive neurons in entorhinal cortex layer II selectively express intracellular amyloid in early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 93, 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P (2005) Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci 8, 1051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. DeBoer SR, Dolios G, Wang R, Sisodia SS (2014) Differential release of β-amyloid from dendrite- versus axon-targeted APP. J Neurosci 34, 12313–12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Gouras GK (2013) Convergence of synapses, endosomes, and prions in the biology of neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Cell Biol 2013, 141083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Ubelmann F, Burrinha T, Salavessa L, Gomes R, Ferreira C, Moreno N, Guimas Almeida C (2017) Bin1 and CD2AP polarise the endocytic generation of beta-amyloid. EMBO Rep 18, 102–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Sadleir KR, Kandalepas PC, Buggia-Prévot V, Nicholson DA, Thinakaran G, Vassar R (2016) Presynaptic dystrophic neuritessurrounding amyloid plaques are sites of microtubule disruption,BACE1 elevation, and increased Aβ generation in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 32, 235–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Saura CA, Chen G, Malkani S, Choi SY, Takahashi RH, Zhang D, Gouras GK, Kirkwood A, Morris RG, Shen J (2005) Conditionalinactivation of presenilin 1 prevents amyloid accumulation andtemporarily rescues contextual and spatial working memoryimpairments in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. JNeurosci 25, 6755–6764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Sannerud R, Esselens C, Ejsmont P, Mattera R, Rochin L, Tharkeshwar AK, De Baets G, De Wever V, Habets R, Baert V, Vermeire W, Michiels C, Groot AJ, Wouters R, Dillen K, Vints K, Baatsen P, Munck S, Derua R, Waelkens E, Basi GS, Mercken M, Vooijs M, Bollen M, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Bonifacino JS, Van Niel G, De Strooper B, Annaert W (2016) Restricted location of PSEN2/γ-secretase determines substrate specificity and generates an intracellular Aβ pool. Cell 166, 193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Buxbaum JD, Gandy SE, Cicchetti P, Ehrlich ME, Czernik AJ, Fracasso RP, Ramabhadran TV, Unterbeck AJ, Greengard P (1990) Processing of Alzheimer beta/A4 amyloid precursor protein: Modulation by agents that regulaterotein phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87, 6003–6006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Costes SV, Daelemans D, Cho EH, Dobbin Z, Pavlakis G, Lockett S (2004) Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein-protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys J 86, 3993–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82, 239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H (2002) Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 58, 1791–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Levine DN, Lee JM, Fisher CM (1993) The visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease: A clinicopathologic case study. Neurology 43, 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Hashimoto M, Bogdanovic N, Volkmann I, Aoki M, Winblad B, Tjernberg LO (2010) Analysis of microdissected human neurons by a sensitive ELISA reveals a correlation between elevated intracellular concentrations of Abeta42 and Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol 119, 543–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, Viola KL, Klein WL (2007) Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 27, 796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Wang HY, Lee DH, D’Andrea MR, Peterson PA, Shank RP, Reitz AB (2000) beta-Amyloid(1-42) binds to alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with high affinity. Implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Biol Chem 275, 5626–5632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Laurén J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM (2009) Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synapticplasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature 457, 1128–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Cissé M, Halabisky B, Harris J, Devidze N, Dubal DB, Sun B, Orr A, Lotz G, Kim DH, Hamto P, Ho K, Yu GQ, Mucke L (2011) Reversing EphB2 depletion rescues cognitive functions in Alzheimermodel. Nature 469, 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Kam TI, Song S, Gwon Y, Park H, Yan JJ, Im I, Choi JW, Choi TY, Kim J, Song DK, Takai T, Kim YC, Kim KS, Choi SY, Choi S, Klein WL, Yuan J, Jung YK (2013) FcγRIIb mediates amyloid-β neurotoxicity and memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Invest 123, 2791–2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Kim T, Vidal GS, Djurisic M, William CM, Birnbaum ME, Garcia KC, Hyman BT, Shatz CJ (2013) Human LilrB2 is a β-amyloid receptor and its murine homolog PirB regulates synaptic plasticity in an Alzheimer’s model. Science 341, 1399–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Renner M, Lacor PN, Velasco PT, Xu J, Contractor A, Klein WL, Triller A (2010) Deleterious effects of amyloid β oligomers acting as an extracellular scaffold for mGluR5. Neuron 66, 739–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Fogel H, Frere S, Segev O, Bharill S, Shapira I, Gazit N, O’Malley T, Slomowitz E, Berdichevsky Y, Walsh DM, Isacoff EY, Hirsch JA, Slutsky I (2014) APP homodimers transduce an amyloid-β-mediated increase in release probability at excitatory synapses. Cell Rep 7, 1560–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Zhang Z, Paganetti PA, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Staufenbiel M, Mautino J, Vigo FS, Sommer B, Yankner BA (2000) Amyloid beta interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: Aotential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 3, 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Shaked GM, Kummer MP, Lu DC, Galvan V, Bredesen DE, Koo EH (2006) Abeta induces cell death by direct interaction with its cognate extracellular domain on APP (APP 597-624). FASEB J 20, 1254–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Pickett EK, Koffie RM, Wegmann S, Henstridge CM, Herrmann AG, Colom-Cadena M, Lleo A, Kay KR, Vaught M, Soberman R, Walsh DM, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL (2016) Non-fibrillar oligomericamyloid-β within synapses. J Alzheimers Dis 53, 787–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Palop JJ, Mucke L (2010) Amyloid-beta-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: From synapses toward neural networks. Nat Neurosci 13, 812–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Abramov E, Dolev I, Fogel H, Ciccotosto GD, Ruff E, Slutsky I (2009) Amyloid-beta as a positive endogenous regulator of release probability at hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci 12, 1567–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Puzzo D, Privitera L, Leznik E, Fà M, Staniszewski A, Palmeri A, Arancio O (2008) Picomolar amyloid-beta positively modulatessynaptic plasticity and memory in hippocampus. JNeurosci 28, 14537–14545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Wang HW, Pasternak JF, Kuo H, Ristic H, Lambert MP, Chromy B, Viola KL, Klein WL, Stine WB, Krafft GA, Trommer BL (2002) Soluble oligomers of β amyloid (1-42) inhibit long-term potentiation but not long-term depression in rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res 924, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Frykman S, Hur JY, Frånberg J, Aoki M, Winblad B, Nahalkova J, Behbahani H, Tjernberg LO (2010) Synaptic andendosomal localization of active gamma-secretase in rat brain. PLoS One 5, e8948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Takahashi RH, Capetillo-Zarate E, Lin MT, Milner TA, Gouras GK (2010) Co-occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease ß-amyloid and τ pathologies at synapses. Neurobiol Aging 31, 1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Lin MT, Beal MF (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443, 787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Clark TA, Lee HP, Rolston RK, Zhu X, Marlatt MW, Castellani RJ, Nunomura A, Casadesus G, Smith MA, Lee HG, Perry G (2010) Oxidative stress and its implications for future treatments and management of Alzheimer disease. Int J Biomed Sci 6, 225–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Almeida CG, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, Greengard P, Lin MT, Snyder EM, Gouras GK (2005) Beta-amyloid accumulation in APP mutant neurons reduces PSD-95 and GluR1 in synapses. Neurobiol Dis 20, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gray level images of Fig. 1B, C. Accumulation of exogenously added Aβ1-42 is more pronounced in (A) excitatory CamKII-positive compared to (B) inhibitory GAD67-positive neurons.

γ-secretase inhibition leads to greater AβPP CTF accumulation in axons compared dendrites in cortical primary neurons. Immunofluorescent labeling of AβPP/PS1 primary cortical neurons treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. AβPP CTF-accumulation, as seen by C-terminal specific AβPP antibody 369, is increased in both tau-1 positive axons and MAP2 positive dendrites after 17 h DAPT treatment compared to control. However, the increase in AβPP CTF labeling after 17 h DAPT treatment is greater in axons compared to dendrites. Scale bars 50 μm.