Abstract

Background

Patients with relapsed and refractory solid tumors have poor prognosis. Recent advances in genomic technology have made it feasible to screen tumors for actionable mutations, with the anticipation this may provide benefit to patients.

Methods

Pediatric oncologists were emailed an anonymous 34 question survey assessing their willingness to offer rebiopsy for patients with relapsed disease for the purpose of tumor genomic profiling. They were presented with two scenarios evaluating morbidity and invasiveness of the procedures using the clinical examples of medulloblastoma and Ewing sarcoma.

Results

195 pediatric oncologists responded to the questionnaire. Morbidity and invasiveness of the procedure demonstrated significant differences in provider willingness to refer their patients for rebiopsy. The pre-test probability was a major variable influencing provider willingness to offer rebiopsy. Respondents were more likely to offer rebiopsy if there is a high likelihood the results will impact clinical management than for histologic confirmation alone (mean 89% vs. 56% p=0.017). Compared to the rate of rebiopsy for histologic confirmation, significantly fewer providers are willing to offer rebiopsy if they are led to believe there is a low likelihood of finding an actionable mutation (mean 45% vs. 56%, p=0.021).

Conclusion

The scenario defined pre-test probability of finding an actionable mutation is influential in determining provider willingness to offer rebiopsy for the purpose of tumor genomic profiling. Further research is warranted to evaluate the benefit of tumor genomic profiling on patient outcomes.

Keywords: practice patterns, tumor genomic profiling, pediatric, relapsed cancer

Introduction

In contrast to the steep decline seen over the past several decades in the mortality rates for childhood leukemia and lymphoma, the decline in the mortality rates for pediatric solid tumors has been modest, and patients with relapsed and refractory solid tumors have a very poor prognosis.1,2 Particularly poor outcomes have been highlighted in recent pediatric phase II trials for patients with relapsed solid tumors, with a one-year progression-free survival of less than 20%.3,4,5 Given these poor outcomes and concern that conventional treatments may provide minimal benefit, novel approaches are needed to improve cure rates.

Recent advances in genomic technology have provided platforms to feasibly screen tumors for actionable mutations, or alterations in genes that can be targeted with novel drug therapy, with the anticipation that the knowledge of the molecular drivers of the disease may provide benefit to patients.6 An analysis of patients referred for tumor molecular profiling at MD Anderson revealed that patients treated with matched therapy, compared to those enrolled on clinical trials with nonmatched therapy, had a higher rate of objective response (12 vs. 5%), prolonged median progression-free survival (3.9 vs. 2.2 months), and prolonged median overall-survival (11.4 vs. 8.6 months).7

The assessment of tumors for actionable mutations requires adequate tissue in order to perform the analysis. This requires the child to undergo a biopsy, which may be an invasive procedure with risk of morbidity. Original tumor specimens are not always accessible, nor are they necessarily representative of the biology of the relapsed disease.

There are no established practice guidelines for biopsying the tumors of patients who have relapsed. There is precedent in pediatrics for requiring biopsy and submission of a specimen for biology companion studies for participation on clinical trials. However, in tumor profiling, while the biopsy is necessary for participation, it offers no guarantee that the analysis will guide the treatment plan.8,9 Benefits of tumor profiling must be weighed by the probability of finding an actionable mutation versus the risk of the procedure.10

This ethical dilemma is faced by practitioners on a daily basis due to the readily available commercial tumor profiling tests. Many of the commercially available tests are marketed directly to consumers. An internet content analysis study identified 32 websites marketing directly to consumers somatic tumor analysis for the purpose of personalized cancer care.11

This survey evaluates the views of pediatric oncologists on the role of biopsying relapsed tumors for the purpose of tumor genomic profiling and assesses the variables that impact providers’ decisions in referring their patients for rebiopsy of the relapsed disease.

Methods

Subjects

The email addresses of 812 practicing pediatric oncologists were obtained via hospital websites and published manuscripts. Pediatric oncologists were emailed a link to an anonymous survey on surveymonkey.com. The pediatric oncologists were sent two subsequent reminder emails to maximize the response rate. The research protocol and survey were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Survey Instrument

The instrument consisted of an internet-based survey comprised of 34 questions involving clinical scenarios designed to address the following domains: physician willingness to biopsy relapsed tumors, invasiveness, morbidity, and ethical beliefs. The scenarios involved children with relapsed or refractory medulloblastoma or Ewing sarcoma, and included questions to evaluate the effect of variations of likelihood of benefit, invasiveness, and morbidity of the surgical procedures and the willingness of providers to offer rebiopsy for the purpose of genomic profiling (Supplementary Figure 1). A previously validated survey tool was also included to evaluate provider self-reported confidence and knowledge within specific areas of genomic profiling.12 Survey items were vetted with experts in pediatric oncology, clinical genomics, medical ethics, and survey methodology to establish face validity.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means, medians, standard deviations and ranges were computed for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. In addition, bivariate associations between provider demographic characteristics and provider views on genomic profiling of relapsed solid tumors were evaluated by means of t-test for continuous variables, and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Results

Demographics

The survey was sent to 812 pediatric oncologists, of whom 195 responded and 159 responders completed the entire survey, for an overall response rate and survey completion rate of 24% and 20%, respectively. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are described in Table 1. The respondents varied in their current usage of tumor genomic profiling: 30% reported referring greater than 5 patients, 49% referring 1–5 patients and 21% did not refer any patients in the past year (Figure 1). Providers are more likely to have referred greater than 5 patients in the past year for tumor genomic profiling if they spend more than 20% of their time performing basic science research (47% vs. 17%, p<0.0001, Supplementary Figure 2); work in divisions with greater than 100 newly diagnosed oncology patients per year (43% vs. 12%, p<0.0001); and, if they have greater confidence in their ability to interpret the results of genomic profiling (35% vs. 17%, p=0.03).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 92 (58.6) |

| Female | 65 (41.4) |

| Specialization | |

| General Oncology | 85 (54.5) |

| Hematology | 35 (22.4) |

| CNS tumors | 21 (13.5) |

| Germ Cell Tumors | 18 (11.5) |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | 55 (35.3) |

| Neuroblastoma | 33 (21.2) |

| Sarcoma | 55 (35.3) |

| Survivorship | 11 (7.1) |

| Transplant | 18 (11.5) |

| Wilms Tumor | 19 (12.2) |

| Years out of fellowship training | |

| <10 years | 77 (49.4) |

| >10 years | 79 (50.6) |

| Number of newly diagnosed patients seen annually at center | |

| <100 patients | 72 (46.2) |

| >100 patients | 84 (53.8) |

| Time dedicated to basic science research | |

| 0–20% | 93 (59.2) |

| >20% | 64 (40.8) |

| Time dedicated to clinical care | |

| 0–20% | 33 (21.1) |

| 21–40% | 27 (17.3) |

| 41–60% | 35 (22.4) |

| 61–80% | 30 (19.2) |

| >80% | 31 (19.9) |

Fig. 1.

Percent of providers who have referred patients with relapsed or refractory tumors for rebiopsy for tumor genomic studies in the past year.

Willingness to Rebiopsy

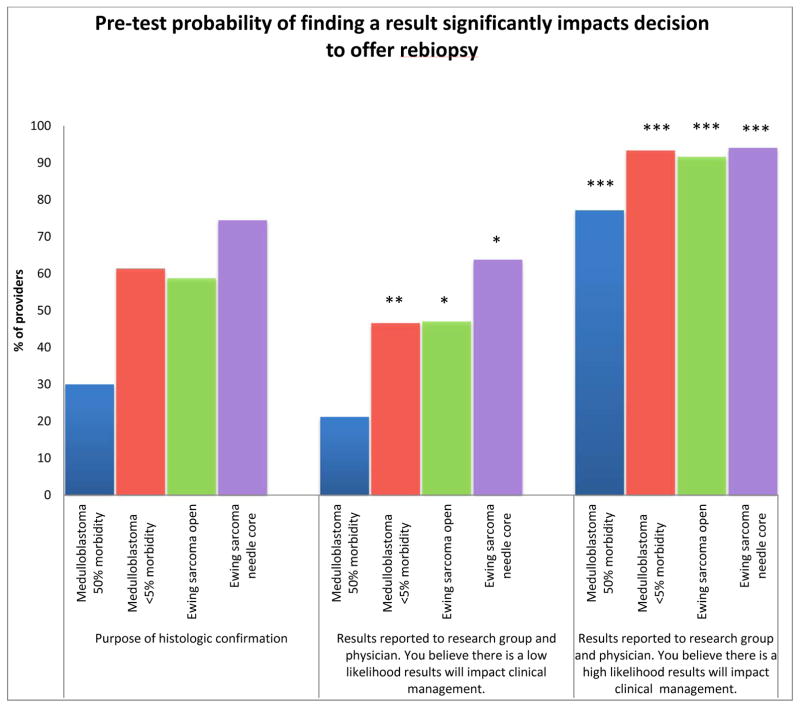

The respondents’ willingness to offer rebiopsy for the purpose of histologic confirmation is negatively correlated with the degree of morbidity and invasiveness presented in the scenario. In the scenario of medulloblastoma, 30% of respondents are willing to offer rebiopsy for histologic confirmation when there is high morbidity, compared to 61% when the morbidity is low (p<0.0001). Fewer respondents are likely to offer a more invasive open procedure for histologic confirmation of relapsed Ewing sarcoma, compared to those who would offer a needle or core biopsy for the same purpose (59% vs. 74%, p=0.0032).

The likelihood of finding an actionable mutation is a major variable influencing provider willingness to offer rebiopsy for the purpose of genomic profiling. The respondents are more likely to offer rebiopsy if they are told that there is a high likelihood the results will impact clinical management than for histologic confirmation alone (mean 89% vs. 56% p=0.017) (Figure 2). In contrast, significantly fewer providers are willing to offer rebiopsy if they are told there is a low likelihood of finding an actionable mutation when compared to the rate for the purpose of histologic confirmation alone, (mean 45% vs. 56%, p=0.021).

Fig. 2.

Pretest probability of finding an actionable result that will affect clinical management significantly impacts providers’ decision to offer rebiopsy of relapsed or refractory solid tumors for the purpose of genomic profiling in all presented scenarios. Compared to providers’ likelihood to offer rebiopsy for histologic confirmation within the same scenario. (***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05).

More providers are willing to offer a highly morbid procedure if they are told there is a high likelihood of finding an actionable mutation, when compared to a procedure associated with a low morbidity if they are told there is a low likelihood of finding an actionable mutation (77% vs. 47%, p<0.0001). Similarly, more providers would offer an invasive procedure in the Ewing sarcoma scenario if they believe that there is a high likelihood the results will impact clinical management, compared to a less invasive procedure with a low likelihood of finding a result (91% vs. 64% p<0.0001).

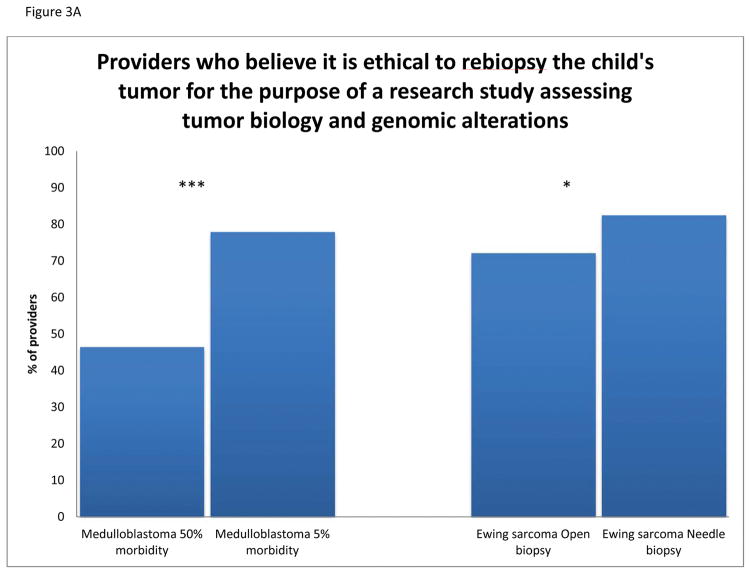

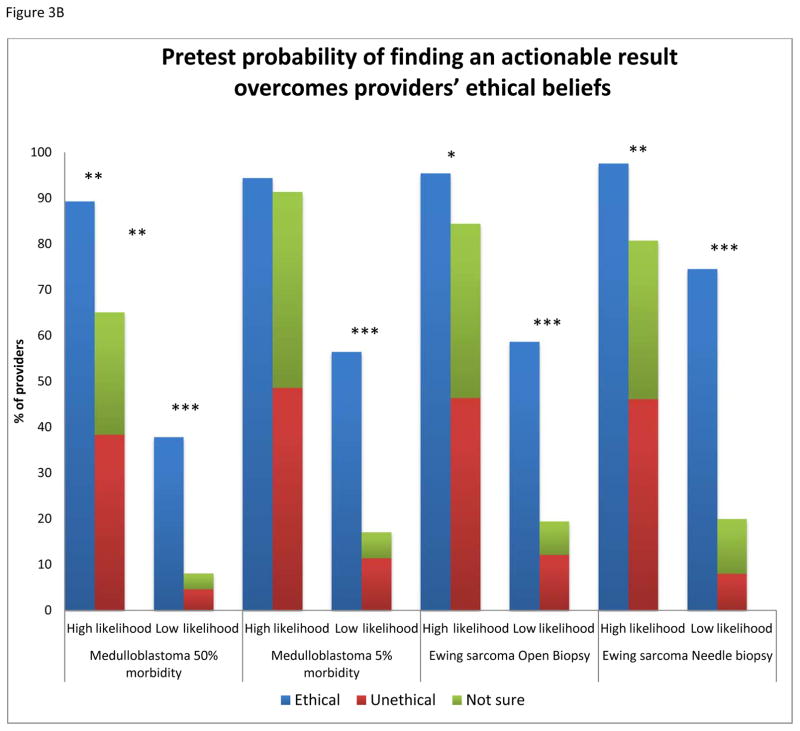

Ethics

More respondents feel that it is ethical to offer rebiopsy if the procedure is associated with a low rate of morbidity versus a high rate of morbidity (78% vs. 47%, p<0.0001) (Figure 3A). Likewise, fewer respondents find it ethical to offer an open biopsy versus a less invasive procedure for the purpose of genomic profiling (72% vs. 83%, p=0.039). Of the 47% of providers who believe it is ethical to offer rebiopsy in the scenario with high morbidity, 89% would offer rebiopsy if there is a high likelihood of finding an actionable mutation. Of the providers who deem rebiopsy of a medulloblastoma with 50% morbidity as unethical or unsure, 65% are willing to offer rebiopsy when they are told there is a high likelihood of finding an actionable mutation (Figure 3B). In the high and low morbidity medulloblastoma scenarios as well as the more invasive Ewing sarcoma scenario, if the respondents thought the procedure to be unethical or were uncertain, they were more likely to offer rebiopsy if they were led to believe there is a high likelihood of finding an actionable mutation than those who considered the procedure ethical but were led to believe there was a low likelihood of finding an actionable mutation (p=0.008, p<0.0001, p=0.007, respectively).

Fig. 3.

A: Providers (%) who believe it is ethical to rebiopsy a solid tumor in a pediatric patient for the purpose of a research study assessing tumor biology and genomic alterations, compared by morbidity and invasiveness. B: Providers’ ethical opinions of rebiopsy displayed by scenario, with the effect of pretest probability on their beliefs and willingness to offer rebiopsy. (***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05).

Genomic Confidence

Providers overall expressed confidence in their ability to incorporate tumor genomic profiling in their practice in the following domains: identifying consultants with expertise in integrating genomic information into patient care (87%), explaining genomic concepts to patients (80%), providing psychosocial support to patients coping with adverse prognostic implications from genomic results (78%), interpreting genomic results within their specific specialty (72%) and making treatment recommendations based on genomic information (62%) (Supplementary Figure 3A). Provider confidence in interpreting genomic results was not associated with a statistically significant change in physician decision to offer their patients rebiopsy.

Pediatric oncologists who spend greater than 20% of their time performing basic science or translation research are more confident in their ability to explain genomic concepts to patients (91 vs. 72%, p=0.002), to interpret genomic results within their specialty (87% vs. 62%, p=0.03) and to make treatment recommendations based on genomic information (76% vs. 53%, p=0.006) compared with those who spend less time in research (Supplementary Figure 3B). The number of years of experience and the number of newly diagnosed patients treated annually were not significantly associated with the providers’ confidence in interpreting genomic data in any of the parameters. Men were more confident than women in their abilities to explain genomic concepts to patients (86% vs. 72%, p=0.04) and to provide psychosocial support (87% vs. 66%, p=0.003) (Supplementary Figure 3C).

Perception of Benefit

Over half of providers believe that 20% or less of patients will directly benefit from tumor genomic profiling (Supplementary Figure 4A). In all scenarios, regardless of the perceived benefit to patients, providers are more likely to offer rebiopsy if there is a high likelihood of finding an actionable mutation (p<0.0001 for all scenarios) (Supplementary Figure 4B). Providers who completed fellowship less than 10 years ago are more likely to feel that greater than 20% of their patients are likely to benefit from tumor genomic profiling (53% vs. 35%, p=0.035).

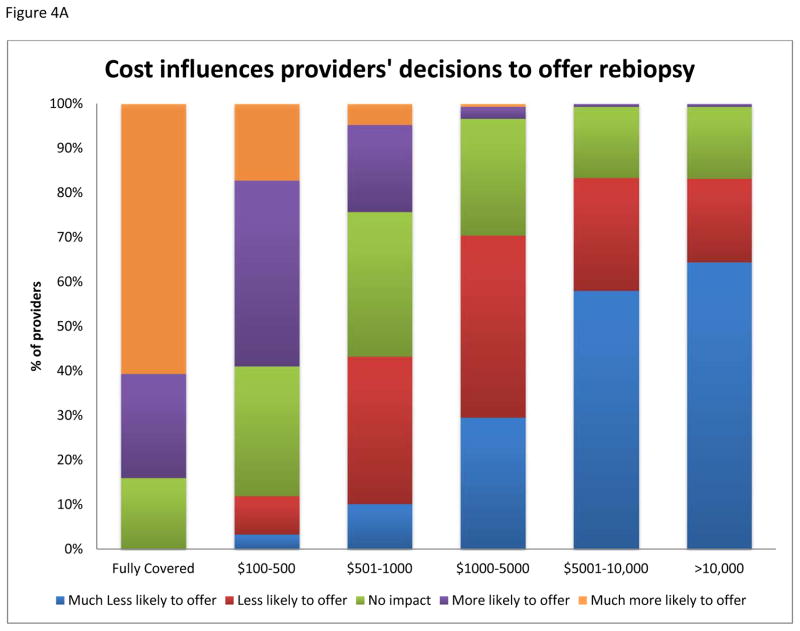

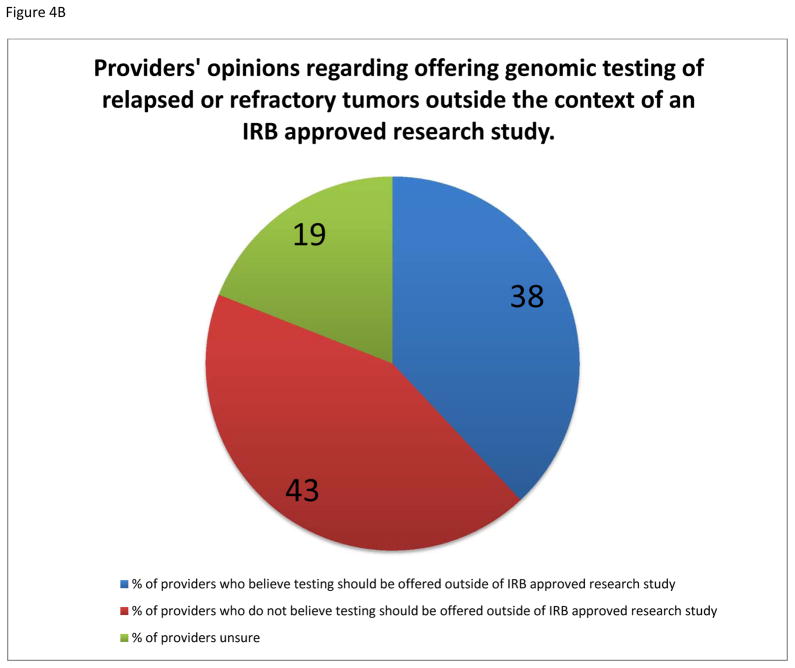

Respondents were divided regarding the appropriateness of performing genomic profiling of relapsed tumors outside the context of an IRB approved study, with 38% agreeing, 43% disagreeing, and 19% unsure of the importance (Figure 4B). The majority of providers agree that it is imperative for the genomic profiling to be performed in a CLIA approved laboratory.

Fig. 4.

A: Influence of costs on providers’ willingness to offer rebiopsy of relapsed or refractory solid tumors for genomic profiling to families of pediatric patients. B: Providers’ opinions regarding the need for IRB approved study to offer tumor genomic profiling to their patients.

Discussion

In surveying pediatric oncology views about the role of rebiopsy for the purpose of genomic profiling of relapsed disease, this study finds that the scenario defined likelihood of finding an actionable mutation was highly influential on the providers’ decision to offer rebiopsy. The degree of morbidity and invasiveness associated with the procedure, as well as the ethical beliefs of the provider, also influence the providers’ willingness to offer rebiopsy to their patients.

The majority of the respondents in this survey indicated their willingness to offer their patients rebiopsy if they are told that there is a high probability of finding an actionable mutation. Yet, greater than half of the respondents believe that less than 20% of their patients will benefit from tumor genomic profiling. This discrepancy might be explained by understanding that the probability of finding an actionable mutation may vary by diagnosis. When told the patient has a high likelihood of finding an actionable mutation, there is the supposition that this patient has features which place him in the subset likely to derive benefit. Another possible explanation for this disparity may be the respondents’ concerns regarding access to therapeutic agents targeting the actionable mutations, especially in the pediatric population, or that the agents currently available may not necessarily generate a response in their patients even if they have an actionable mutation.

At baseline, we found that providers who devote greater than 20% of their time conducting basic science research are significantly more likely to have referred more than five patients for tumor genomic profiling. A significantly greater number of these individuals were also likely to report confidence in their abilities to “explain genomic concept to patients”, “interpret genomic results”, and “make treatment recommendations based on genomic information”. This implies that the providers’ confidence in their ability to interpret the results of genomic profiling may play a role in the number of patients they refer to genomic testing. Given the number of respondents, a multivariate analysis could not be performed to validate this relationship. However, it does suggest a possible role of education or streamlining the reporting of the results to improve the understanding of the providers.

In this survey, men were more likely than women to report confidence with their ability to explain genomic concepts to patients as well as provide psychosocial support. This in part may be explained by the fact that men comprised a much larger proportion (72%) of the individuals who spent greater than 20% of their time conducting basic science research (data not shown). However, there are may be other factors, beyond the scope of this instrument, that may explain this finding: while men were significantly more likely to report confidence in providing psychosocial support, respondents who spent greater than 20% of their time conducting basic science research were less likely to report confidence in that domain, which did not reach the level of statistical significance.

This study examines the possible forces influencing the decision of pediatric oncologists to refer their patients for biopsy for the purpose of tumor genomic profiling. Prior manuscripts have examined the ethical considerations of tissue collection for research purposes.8–10,13 Children as protected subjects pose an even greater ethical concern, as any additional procedure above minimal risk for the purpose of research merits greater scrutiny.

However, in the case of biopsy for tumor genomic profiling the purpose of the biopsy is not just for research, but also for the direct benefit of the patient. This is complicated further by the expectation an actionable mutation will be found in only a subset of patients. Furthermore, while there have been encouraging results in some disease such as lung cancer in respects to targeted therapy for patients with EGFR or ALK mutations, there have been limited data for the outcomes of tumor genomic profiling in pediatric cancer.

Recently, a survey of medical oncologists at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital examined physicians’ attitudes about tumor genomic profiling. Similar to their pediatric oncology counterparts in this survey, the majority of medical oncologists were confident in their ability to interpret the results of tumor genomic profiling. Also similarly, the physicians varied in their belief of the percentage of patients for which this testing would be applicable.12 This may reflect the yet undefined role and benefit of this evolving technology.

The perception of direct benefit of genomic profiling of relapsed / refractory solid tumors from the pediatric oncologists surveyed is in line with preliminary results of tumor profiling studies in this patient population.14,15 This suggests a relatively high level of proficiency with genomic data in the pediatric oncology community. However, providers who completed fellowship less than 10 years ago were more likely to believe that greater than 20% of their patients will benefit from tumor genomic profiling. This may be revealing of gap in the education of trainees about the potential value and limitations of this powerful technology for their patients.

There are several potential limitations to this study. One limitation is the small sample size, which is in part due to the limited number of pediatric oncologists, and the response rate, which may impart a degree of non-response bias. Another limitation is the scope of the instrument used in the survey. The data reflect the participants’ responses to hypothetical situations and may not accurately reflect their practice patterns. Furthermore, the study was cross-sectional analyzing bivariate relationships, so no causal inferences can be made, but this work can inform future inquiries in this area of research.

Tumor genomic profiling plays an increasing role in the care of pediatric oncology patients. The President’s announcement of the Precision Medicine Initiative heralds the arrival of a new era in cancer research in which molecular diagnostics will play an integral role in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.16 This study provides an early step toward understanding providers’ perceptions and potential barriers to rebiopsy for the purpose of acquiring this new variety of clinical data.

Further research is necessary to evaluate the practice patterns of oncologists with respect to use of this evolving technology. Likewise, further research is warranted to evaluate the benefit of tumor genomic profiling on patient outcomes with the understanding that such studies will be complicated by issues with design.

Supplementary Material

SYNOPSIS.

This study reports the results of a survey evaluating the factors that determine the willingness of pediatric oncologist to offer rebiopsy to their patients for the purpose of tumor genomic profiling.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None. No conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for Children and Adolescents With Cancer: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(15):2625–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, Reaman GH, Seibel NL. Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer. 2014;120(16):2497–2506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendy B, London RB, Weigel Brenda, Fox Elizabeth, Van Ryn Collin, Naranjo Arlene, Mark D, Krailo CHA, Park Julie R. Historical gold standard for time to progression (TTP) and progression-free survival (PFS) from relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma modern era (2002–2014) patients. 2014 ASCO Annual Meeting. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leary SE, Wozniak AW, Billups CA, et al. Survival of pediatric patients after relapsed osteosarcoma: the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. Cancer. 2013;119(14):2645–2653. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald TJ, Vezina G, Stewart CF, et al. Phase II study of cilengitide in the treatment of refractory or relapsed high-grade gliomas in children: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(10):1438–1444. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran B, Dancey JE, Kamel-Reid S, et al. Cancer Genomics: Technology, Discovery, and Translation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(6):647–660. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, Hong DS, et al. Personalized medicine for patients with advanced cancer in the phase I program at MD Anderson: validation and landmark analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(18):4827–4836. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson BD, Adamson PC, Weiner SL, McCabe MS, Smith MA. Tissue Collection for Correlative Studies in Childhood Cancer Clinical Trials: Ethical Considerations and Special Imperatives. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(23):4846–4850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peppercorn J. Toward Improved Understanding of the Ethical and Clinical Issues Surrounding Mandatory Research Biopsies. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(1):1–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peppercorn J, Shapira I, Collyar D, et al. Ethics of Mandatory Research Biopsy for Correlative End Points Within Clinical Trials in Oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(15):2635–2640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray SW, Cronin A, Bair E, Lindeman N, Viswanath V, Janeway KA. Marketing of personalized cancer care on the web: an analysis of internet websites. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray SW, Hicks-Courant K, Cronin A, Rollins BJ, Weeks JC. Physicians’ Attitudes About Multiplex Tumor Genomic Testing. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(13):1317–1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Protection of Human Subjects, Part 46 Code of Federal Regulations, §46.102 (2009).

- 14.Parsons DW. Evaluating the implementation and utility of clinical tumor exome sequencing in the pediatric oncology clinic: Early results of the BASIC3 study. Cancer Res; Proceedings of the AACR Special Conference on Pediatric Cancer at the Crossroads: Translating Discorvery into Improved Outcomes; Nov 3–6, 2013.2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janeway KA. Clinical genomics. Cancer Res; Proceedings of the AACR Special Conference on Pediatric Cancer at the Crossroads: Translating Discovery into Improved Outcomes; Nov 3–6, 2013.2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):793–795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.