Abstract

Correct myelination is crucial for the function of the peripheral nervous system. Both positive and negative regulators within the axon and Schwann cell function to ensure the correct onset and progression of myelination during both development and following peripheral nerve injury and repair. The Sox2 transcription factor is well known for its roles in the development and maintenance of progenitor and stem cell populations, but has also been proposed in vitro as a negative regulator of myelination in Schwann cells. We wished to test fully whether Sox2 regulates myelination in vivo and show here that, in mice, sustained Sox2 expression in vivo blocks myelination in the peripheral nerves and maintains Schwann cells in a proliferative non-differentiated state, which is also associated with increased inflammation within the nerve. The plasticity of Schwann cells allows them to re-myelinate regenerated axons following injury and we show that re-myelination is also blocked by Sox2 expression in Schwann cells. These findings identify Sox2 as a physiological regulator of Schwann cell myelination in vivo and its potential to play a role in disorders of myelination in the peripheral nervous system.

KEY WORDS: Schwann cell, Myelination, Sox2, Repair, Peripheral nervous system, Mouse

Summary: Sox2 promotes both Schwann cell proliferation and macrophage infiltration in peripheral nerves, demonstrating its potential involvement in disorders of myelination.

INTRODUCTION

Schwann cells (SC) are the myelinating glia of the peripheral nervous system (PNS); they myelinate large diameter axons and provide trophic support for both motor and sensory axons. The transcriptional programmes driving both myelination and the dedifferentiation of SCs following injury have been partially characterised and many positive regulators, such as Krox20 (Egr2), Oct6 (SCIP or Tst1), Sox10 and Nfatc4, have been identified by both in vitro and in vivo analysis. However, there is still little data on the potential negative regulators of myelination in vivo that play roles in both the correctly timed onset of myelination and possibly in the pathology of demyelinating neuropathies of the PNS (Topilko et al., 1994; Svaren and Meijer, 2008; Jaegle et al., 1996; Finzsch et al., 2010; Kao et al., 2009; Jessen and Mirsky, 2008).

Although the transcription factors Pax3, Jun (cJun) and Sox2, activation of the Notch pathway, and signalling through Erk1/2 and p38 mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinases have been shown to inhibit myelination of SCs in vitro, there is only direct genetic evidence available for Notch signalling, Erk1/2 and p38 activation regulating these processes in vivo (Yang et al., 2012; Le et al., 2005; Parkinson et al., 2008; Harrisingh et al., 2004; Woodhoo et al., 2009; Doddrell et al., 2012; Jessen and Mirsky, 2008; Napoli et al., 2012; Ishii et al., 2016, 2013; Roberts et al., 2016).

The high mobility group (HMG) domain transcription factor Sox2 has been shown in vitro, using SC/dorsal root ganglion (SC/DRG) co-cultures and adenoviral overexpression of Sox2 in SCs, to inhibit the induction of Krox20 and myelination of axons (Le et al., 2005), but a demonstration of the potential inhibitory role of Sox2 in vivo within the intact peripheral nerve has not yet been provided. In order to test the role of Sox2 in vivo, we have made use of a conditional Sox2IRESGFP allele (Lu et al., 2010), which is activated in a cell-specific manner by crossing with the SC-specific P0-CRE line, and have tested the effects of ongoing Sox2 expression upon PNS myelination and repair. These experiments show, for the first time, that in vivo Sox2 will suppress PNS myelination and re-myelination following injury. In addition, persistent Sox2 expression in the adult nerve is sufficient to induce SC proliferation and an ongoing inflammatory state within the intact peripheral nerve.

RESULTS

Sox2 blocks Krox20-driven expression of myelin-associated proteins

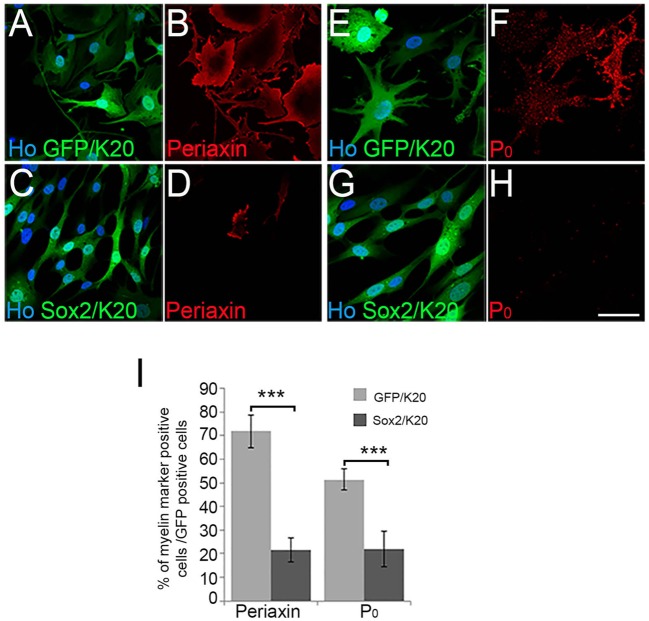

The analysis of mice with a hypomorphic allele of Krox20/Egr2 (Egr2Lo/Lo) showed PNS hypomyelination and continued postnatal expression of the Sox2 transcription factor in SCs (Le et al., 2005). This study also showed that high levels of Sox2 in SCs blocked the in vitro induction of Krox20 by cAMP and myelination in SC/DRG co-cultures. Previous analysis of inhibitors of myelination, e.g. Jun, have shown that Jun can both inhibit the induction of Krox20 in SCs as well as prevent the ability of exogenously expressed Krox20 to induce myelinating SC markers. In this way, Jun acts as an inhibitor of myelination both upstream and downstream of Krox20 function (Parkinson et al., 2004). While Sox2 has been shown to block Krox20 induction in SCs by cAMP (Le et al., 2005), we tested whether maintained Sox2 can also inhibit the action of the pro-myelinating transcription factor Krox20 in inducing myelinating SC markers (Parkinson et al., 2004). In adenoviral co-infection experiments, as expected, Krox20 induced both the expression of myelin protein zero (P0; Mpz) and the myelinating cell marker periaxin in SCs (Parkinson et al., 2003, 2004). Co-expression of Sox2 with Krox20 in SCs showed that Sox2 strongly antagonised Krox20-induced expression of both P0 and periaxin (Fig. 1A-I), confirming, in vitro, that maintained Sox2 expression blocks the myelination programme both upstream and downstream of Krox20 induction in SCs.

Fig. 1.

Sox2 antagonises Krox20-induced myelin protein expression in vitro. (A-H) Immunofluorescence of rat SCs infected with GFP/Krox20- (A,B,E,F) or Sox2/Krox20- (C,D,G,H) expressing adenovirus, showing inhibition of Krox20-driven periaxin (C,D) and P0 expression (G,H) by Sox2. Hoechst stain (Ho) is used to reveal SC nuclei. Scale bars: 20 µm. (I) Percentage of periaxin and P0-positive cells in GFP/K20 and Sox2/K20 adenoviral-infected SCs. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 biological replicate experiments; ***P<0.005.

Sox2 expression inhibits myelination in vivo

We next tested whether Sox2 can act as an inhibitor of myelination in vivo within the intact nerve. A conditional overexpressing allele for Sox2 (Sox2IRESGFP), inserted into the Rosa26 locus, has been described that, upon CRE-mediated recombination, expresses both Sox2 and enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Lu et al., 2010). In order to drive SC-specific expression of Sox2, we used the mP0TOTA-CRE (P0-CRE) line (Feltri et al., 1999) to remove the floxed ‘stop-cassette’ sequence and allow cell-specific expression of Sox2 and GFP in SCs. We have characterised nerves from transgenic CRE+ mice that have either one (Sox2HetOE) or both (Sox2HomoOE) recombinant Rosa26-Sox2IRESGFP alleles and the effects of Sox2 expression upon PNS myelination and repair.

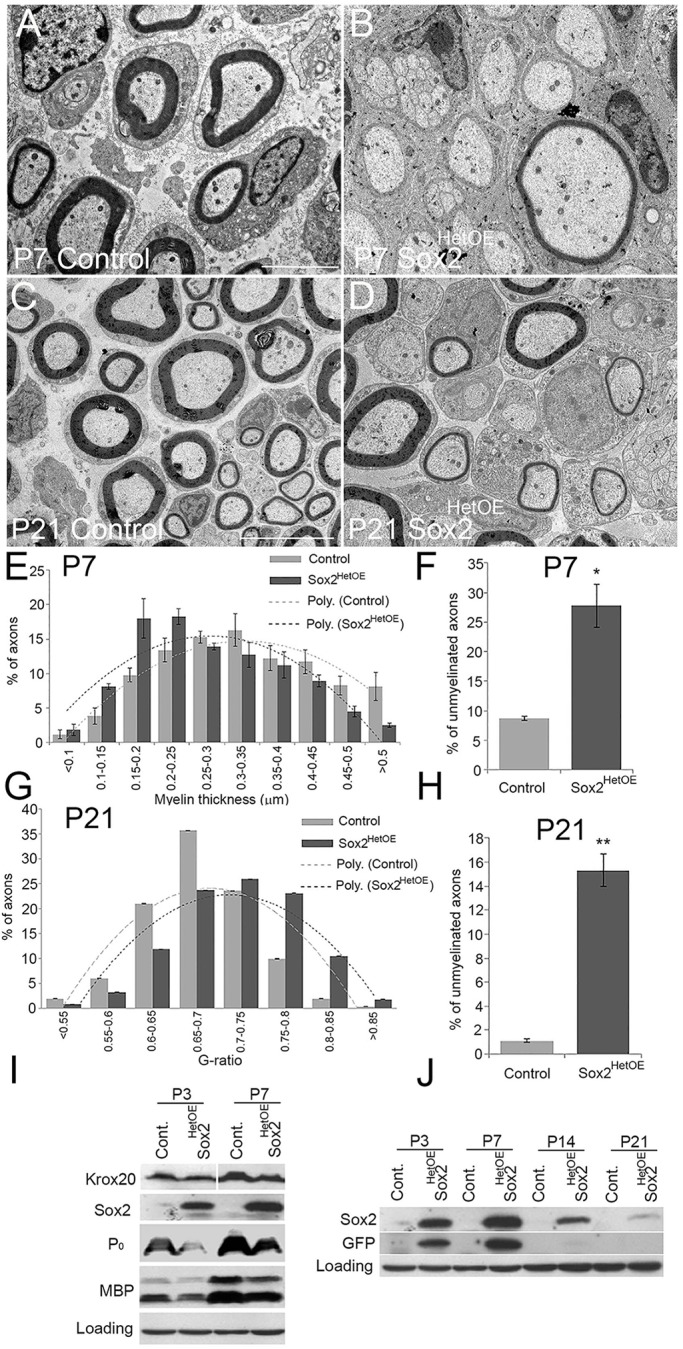

We first analysed sciatic nerves of mice carrying one copy of the Sox2IRESGFP transgene. Rosa26 wild-type/Sox2IRESGFP/CRE+ mice (Sox2HetOE) showed both Sox2 and GFP expression in SCs of the nerve. Sox2 expression in control and Sox2HetOE nerves was confirmed by western blot and immunolabelling (Fig. 2I,J; Fig. S1A-D). These nerves and controls were analysed at postnatal day (P) 7 and P21 by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 2A-D). Although there is no apparent defect at this stage in axonal sorting (SCs appear to make a normal 1:1 relationship with the axons), there is a substantial reduction in myelin thickness at P7 (Fig. 2B,E) and at P21 (Fig. 2D,G) resulting in an increased average G-ratio (0.71±0.003) for Sox2HetOE compared with control (0.68±0.002) at P21. Western blotting of sciatic nerve from control and Sox2HetOE at both P3 and P7 showed decreased Krox20 as well as reduced myelin proteins P0 and myelin basic protein (MBP, Fig. 2I). We also observed significant increases in the numbers of unmyelinated axons at both P7 and P21 in Sox2HetOE nerves compared with controls (Fig. 2F,H).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of myelination in Sox2-overexpressing mice in vivo. (A-D) TEM of sciatic nerves from control P7 control (A) and Sox2HetOE (B) mice, and P21 control (C) and Sox2HetOE (D) mice. Scale bars: 5 µm. (E) The distribution of myelin thickness in P7 control and Sox2HetOE mouse nerves. (F) There is a significant increase in the proportion of unmyelinated axons greater than 1 µm in diameter in the sciatic nerves of P7 Sox2HetOE mice compared with controls. (G) The distribution of the G-ratio of axons in P21 control and Sox2HetOE nerves. n=3 mice of each genotype. (H) There is a significant increase in the population of unmyelinated axons greater than 1 µm in diameter in nerves of P21 Sox2HetOE mice compared with control mice. (F,H) Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype; *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01. (I) Western blots showing the reduction in Krox20, P0 and myelin basic protein (MBP) proteins in P3 and P7 control and Sox2HetOE nerves. (J) Western blots showing Sox2 and GFP expression in postnatal control and Sox2HetOE mice.

Analysing Sox2HetOE animals at later timepoints, we observed that the myelination in the PNS appeared to return to normal. At P60 there was no significant difference in G-ratio compared with control animals (0.65±0.02 for Sox2HetOE compared with 0.66±0.02 for controls), nerve morphology of Sox2HetOE nerves was completely normal at P60 (Fig. 3L; Fig. S1J-L) and electrophysiology of Sox2HetOE nerves showed no changes in nerve conduction velocity at P90 compared with controls (Fig. S1I). We analysed expression of the Sox2IRESGFP transgene in these Sox2HetOE animals and found that the expression of both Sox2 and GFP was high at P7 but declined from P21 onwards and was undetectable at later time points, either by western blot or immunocytochemistry; this decrease in GFP expression was associated with onset of myelination in the Sox2HetOE nerves (Fig. 2J; Fig. S1A-H). We were unable to discern why expression levels of Sox2 and GFP decline in these Sox2HetOE mice, but it does show that loss of Sox2 overexpression in a hypomyelinated nerve from P21 onwards will allow myelination to proceed such that it appears normal by P60 in the mouse PNS.

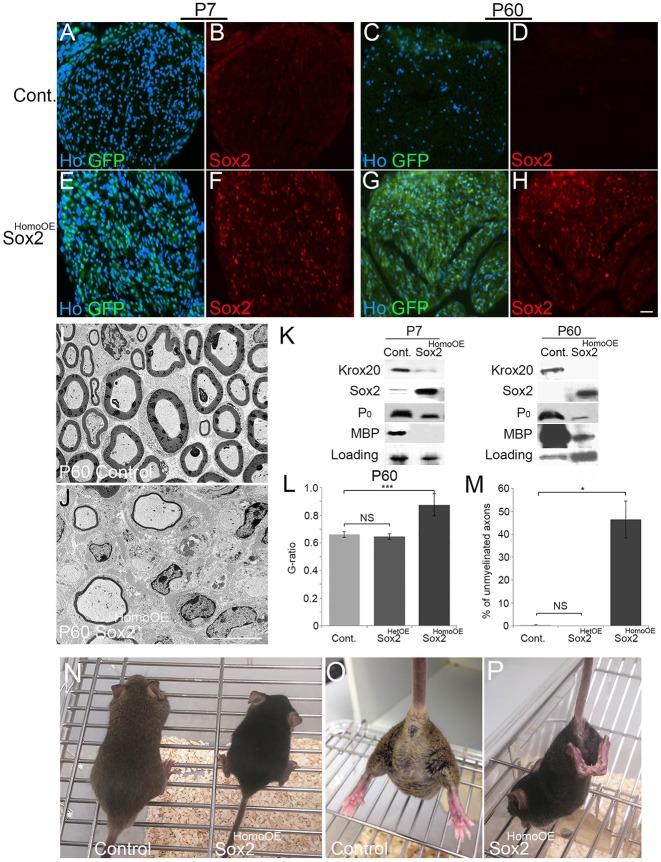

Fig. 3.

Analysis of Sox2 expression and myelination in Sox2HomoOE mice carrying two copies of the Sox2IRESGFP transgene. (A-H) Immunohistochemical analysis of sciatic nerves demonstrates that control nerves do not express GFP or Sox2 at P7 (A,B) or P60 (C,D), whereas Sox2HomoOE nerves have high levels of GFP and Sox2 expression at both P7 (E,F) and P60 (G,H). Scale bar: 40 µm. (I,J) TEM images of control (I) and Sox2HomoOE (J) nerves at P60. Scale bar: 5 µm. (K) Western blots of control and Sox2HomoOE nerves at P7 and P60 showing reduction in Krox20, P0 and MBP expression in vivo mediated by Sox2 expression in SCs. (L,M) G-ratio measurements (L) and numbers of unmyelinated axons greater than 1 µm in diameter (M) in control, Sox2HetOE and Sox2HomoOE nerves at P60. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype; *P<0.05, ***P<0.005. (N) Sox2HomoOE mice (black, on right of picture) were smaller at P60 compared with control animals. (O,P) Sox2HomoOE animals (P) show hind limb clasping when lifted by the tail, which is characteristic of peripheral hypomyelination, when compared with control littermate (O).

Next, we performed crosses to generate animals carrying two copies of the Sox2IRESGFP transgene and examined whether in this case Sox2 expression persisted in the nerve in CRE+ (Sox2HomoOE) animals and effects of such expression. Sox2HomoOE animals showed a similar hypomyelinating phenotype with ongoing Sox2 expression at P7, P14 and P21 time points in CRE+ animals and Sox2 continued to be expressed up to P60, as measured by either immunolabelling or western blot (Fig. 3A-H,K and data not shown).

P60 adult Sox2HomoOE animals were smaller in size compared with controls and showed a typical hindlimb clasping when lifted by the tail (Fig. 3N-P), indicating a possible reduction of PNS myelination. TEM analysis of P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves showed hypomyelination within the adult nerve (Fig. 3I,J), showing that ongoing Sox2 expression will inhibit myelination even at this later time point in vivo. Immunocytochemistry and western blotting of Sox2HomoOE nerves at both P7 and P60 showed reduced levels of Krox20 and of the myelin proteins P0 and MBP (Fig. 3K; Fig. S2A-F,I). Levels of the Sox10 transcription factor protein, a key driver of myelination (Finzsch et al., 2010; Fröb et al., 2012), were unchanged at P7, but actually increased in Sox2HomoOE nerves at P60 (Fig. S2G), presumably due to increased numbers of SCs within the nerve (see below and Fig. 7). Corresponding to the reduction in myelin protein expression, a significant increase in the G-ratio and numbers of unmyelinated axons was observed in Sox2HomoOE nerves at P60 compared with control and Sox2HetOE animals (Fig. 3L,M).

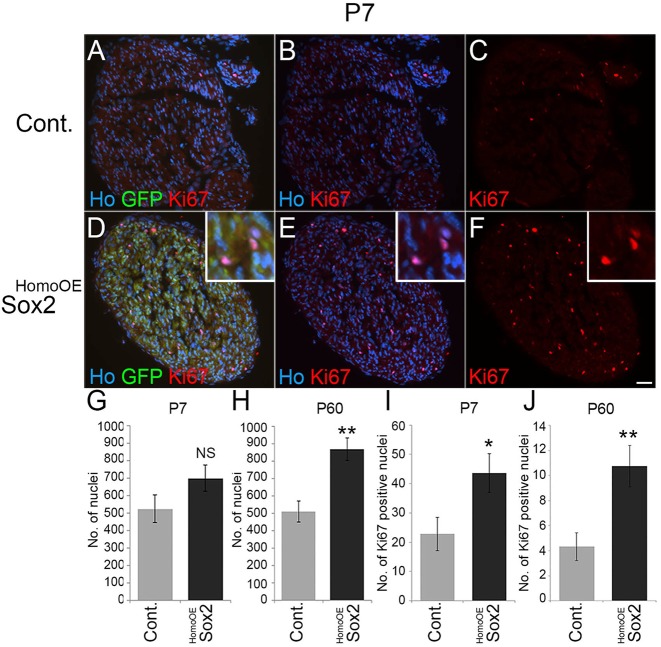

Fig. 7.

SC numbers and proliferation are increased in Sox2-overexpressing nerves. (A-F) Ki67 labelling of sciatic nerves taken from P7 control (A-C) and Sox2HomoOE (D-F) mice. Scale bar: 40 µm. Insets in D-F show higher magnification of Ki67/GFP-positive SCs. (G,H) There is an increase in the number of SC nuclei in P7 (G) and P60 (H) Sox2HomoOE sciatic nerves compared with controls. Numbers given are total nuclei per sciatic nerve transverse section. (I,J) There is a significant increase in the number of GFP/Ki67-positive nuclei in P7 (I) and P60 (J) Sox2HomoOE sciatic nerves. (G-J) Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype at each time point; *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

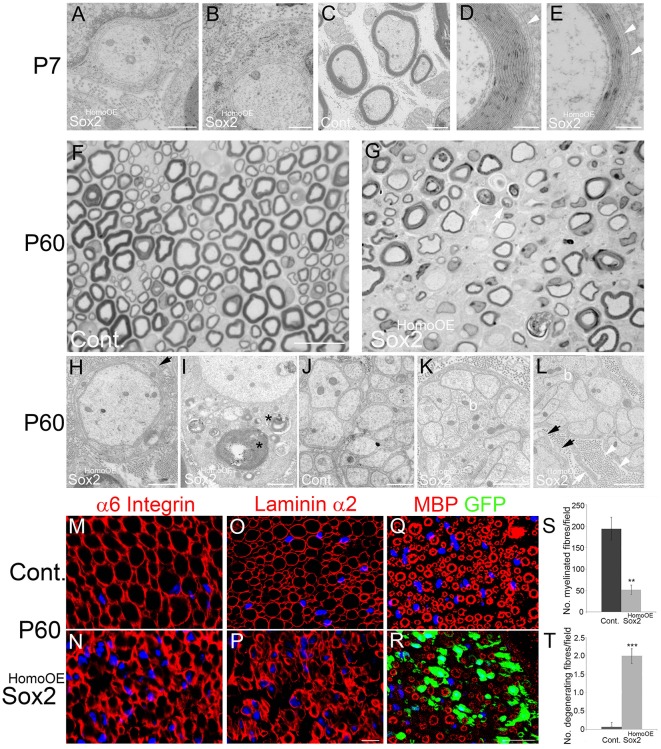

More-detailed examination of P7 and P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves showed a number of additional effects of Sox2 expression upon nerve morphology. At P7, although SCs are making a 1:1 relationship with axons, there is stalling of the ensheathment (Fig. 4A,B). In addition, at this age, where myelination is observed, we see an apparent lack of compaction in the outer myelin membrane layers of the SCs (Fig. 4D,E). At P60, semi-thin and cryostat sections of Sox2HomoOE nerves show reduced myelination, but also evidence of both axonal loss and ongoing myelin breakdown (Fig. 4F,G,Q-T). Additionally, at P60 we saw highly disorganised Remak bundles within the Sox2HomoOE nerves, with groups of small diameter axons not separated by SC cytoplasm, in contrast to control nerves, and observed SCs extending abnormal processes and engulfing collagen fibres (Fig. 4H-L). An examination of basal lamina structure in P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves with α6 integrin and laminin α2 staining showed an abnormal and diffuse staining pattern in Sox2HomoOE nerves when compared with controls (Fig. 4M-P). Similar behaviour was observed using in vitro SC/DRG myelinating co-cultures with Sox2-overexpressing SCs; 21 days after ascorbic acid addition to trigger myelination, Sox2-overexpressing SCs did not associate correctly with axons, produced many cellular processes and very little myelin when compared with controls (Fig. S3).

Fig. 4.

Morphology of P7 and P60 control and Sox2HomoOE nerves. (A-E) P7 sciatic nerves from control (C) and Sox2HomoOE animals (A,B,D,E). Whereas control nerve SCs have formed proper myelin (C), in Sox2HomoOE nerves most SCs are stalled in the 1:1 stage (A,B). (D,E) Where Sox2-overexpressing SCs do form myelin, they often show non-compaction of outer myelin layers (white arrowheads). Scale bars: 500 nm in A,B; 2 µm in C; 200 nm in D,E. (F,G) Semi-thin sections of P60 control (F) and Sox2HomoOE (G) nerves; arrows in G indicate possible axonal loss and demyelination. Scale bar: 20 µm. (H-L) P60 control (J) and Sox2HomoOE (H,I,K,L) nerves. At P60, most axons in Sox2HomoOE nerves are amyelinated and surrounded by redundant SC basal lamina (black arrows in H and L), and several SCs show myelin debris in the cytoplasm (asterisks in I). Remak bundles, which in control nerves show proper SC cytoplasm separating axons (J), show bundles of axons touching each other (‘b’ in K and L) and aberrant SC processes (white arrow in L), the basal lamina of which forms collagen pockets (white arrowheads in L). Scale bars: 1 µm in H-L. (M-R) P60 control (M,O,Q) and Sox2HomoOE (N,P,R) nerve sections immunolabelled with α6 integrin (M,N), laminin α2 (O,P) and myelin basic protein (MBP)/GFP (Q,R). Scale bars: 5 µm in M-P; 25 µm in Q,R. (S,T) Quantification of myelinated (S) and degenerating (T) fibres per field in P60 control and Sox2HomoOE nerves. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype; **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

Sox2 overexpression reduces nerve conduction velocity (NCV), motor function and sensory function

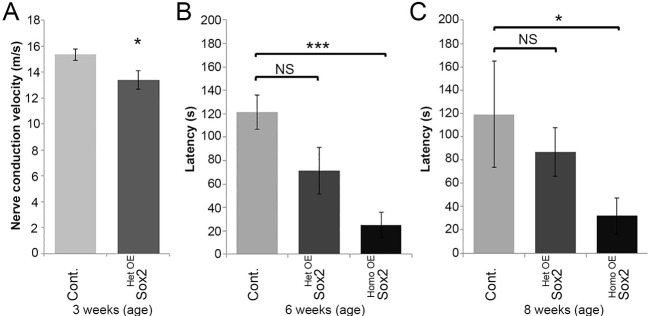

Following on from the molecular characterisation of nerves overexpressing Sox2, we next compared the NCV in control and Sox2HetOE animals. Analysis of compound action potentials revealed that Sox2HetOE nerves have significantly decreased NCVs compared with control nerves at P21 (Fig. 5A; see Fig. S4C for examples of original electrophysiological recordings), although this had corrected by P90 (Fig. S1I), consistent with the normal myelination at this timepoint in these animals (Fig. S1J-L). Next, motor functional analysis was tested using a rotarod with an increasing speed by recording the latency to fall (Saporta et al., 2012; Wrabetz et al., 2006). A significantly reduced latency was observed in Sox2HomoOE mice at both 6 weeks and 8 weeks of age. Although not significant, a slight reduction in latency was observed in Sox2HetOE mice at 6 weeks and 8 weeks of age (Fig. 5B,C).

Fig. 5.

Nerve conduction velocity and motor function is reduced in Sox2-overexpressing animals. (A) The nerve conduction velocities (NCV) of sciatic nerves taken from control (n=11) and Sox2HetOE (n=13) mice at P21. (B,C) Reduction in latency to fall using rotarod testing of control, Sox2HetOE and Sox2HomoOE mice at 6 weeks (B) and 8 weeks (C) of age. 6 weeks control, n=7; Sox2HetOE, n=4; Sox2HomoOE, n=6; 8 weeks control, n=4; Sox2HetOE, n=4; Sox2HomoOE, n=6. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; *P<0.05, ***P<0.005.

Further analysis of sensory function was carried out using toe pinch (pressure) and Von Frey filament (light touch) testing. At 6 weeks, toe pinch testing showed a reduction in the ability of Sox2HomoOE mice to response to pressure stimuli, compared with control and Sox2HetOE mice (Fig. S4A). In testing using Von Frey filaments, we found that Sox2HomoOE mice also had a significantly decreased ability to respond to light touch stimuli compared with control mice (Fig. S4B).

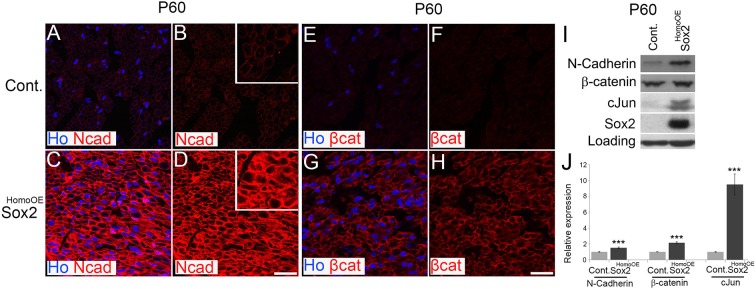

Increased levels of immature SC markers N-cadherin and Jun in adult Sox2HomoOE nerves

N-cadherin is expressed in developing nerve and declines during myelination with a reciprocal upregulation of E-cadherin, but is re-expressed following nerve injury (Crawford et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2006). Expression of Sox2 in SCs has been shown to drive re-localisation of N-cadherin, a cell-surface adhesion molecule, and allow SC clustering in the nerve bridge following injury (Parrinello et al., 2010). Such clustering is effected by the formation of adherens junctions through a calcium-dependent homophilic cadherin-cadherin interaction between SCs (Wanner and Wood, 2002). Immunolabelling of P60 sciatic nerve sections showed a clear increase in N-cadherin levels in SCs from Sox2HomoOE nerves compared with controls with an apparent cell membrane localisation (Fig. 6A-D). Western blotting confirmed an increase in N-cadherin levels in Sox2HomoOE nerves, as well as increased levels of the Jun transcription factor, a marker of promyelinating SCs (Parkinson et al., 2004) (Fig. 6I,J).

Fig. 6.

Expression and localisation of N-cadherin and β-catenin in P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves. (A-H) Immunolabelling of sciatic nerve sections from P60 control (A,B,E,F) and Sox2HomoOE (C,D,G,H) nerves showing localisation and levels of N-cadherin (Ncad; A-D) and β-catenin (βcat; E-H) in SCs. Sections are counterstained with Hoechst (Ho) to reveal nuclei. Scale bar: 20 µm. (I) Western blot showing elevated levels of Sox2, N-cadherin and Jun in P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves. (J) Quantification of western blots in I. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 blots; ***P<0.005.

β-Catenin is an N-cadherin binding partner and has been shown to both colocalise at the SC-axon interface to regulate SC polarity (Lewallen et al., 2011) and to positively regulate SC proliferation in SC-DRG co-cultures (Gess et al., 2008). β-Catenin immunolabelling and western blotting showed slightly raised levels of expression in P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves in vivo (Fig. 6E-J). Corresponding in vitro experiments with rat SCs showed that enforced Sox2 expression alters SC morphology (Fig. S5A,B), localises both N-cadherin and β-catenin to the SC membrane in a calcium-dependent manner (Fig. S5C-J), and increased the levels of both proteins (Fig. S5K); interestingly, expression of a 4-hydroxytamoxifen-regulatable Sox2 (Sox2-ER™) protein in 3T3 fibroblasts was sufficient to drive upregulation and membrane localisation of the N-Cadherin protein after the addition of tamoxifen to this heterologous cell type (Fig. S6A-E).

SC proliferation is increased by Sox2 expression in vivo

In Sox2HomoOE mice, we saw increased numbers of SCs within the nerve from P7 onwards (Fig. 7G,H; Fig. S7). To identify whether Sox2 increased SC proliferation in vivo, we immunolabelled P7 and P60 nerve sections with Ki67. The number of GFP/Ki67-positive nuclei was significantly increased in Sox2HomoOE mice at both P7 and P60 (Fig. 7A-F,I,J); however, no significant increase in Ki67 staining or nuclei number was detected at time points as early as P3 (Fig. S7A-E; data not shown).

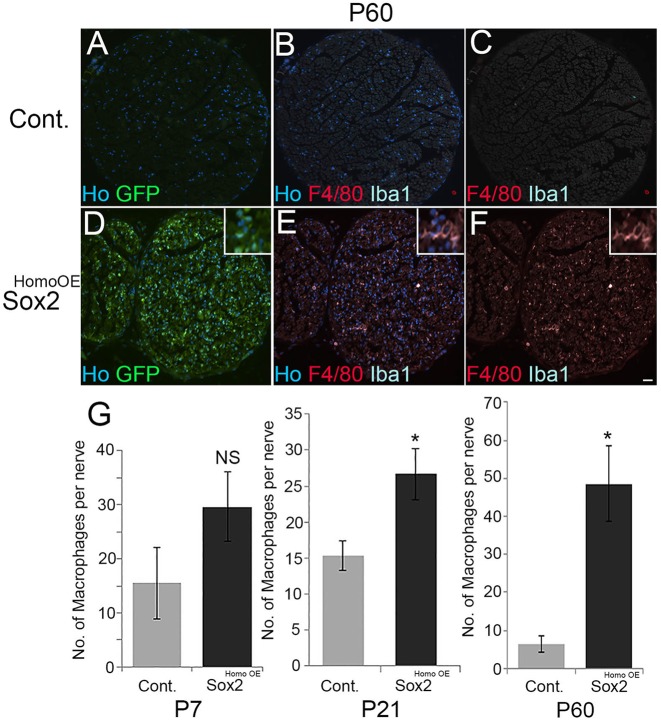

Increased numbers of macrophages in uninjured Sox2-overexpressing nerves

Having observed that increased Sox2 expression maintains SCs in a proliferative non-myelinating state in the adult nerve, and also some myelin breakdown and axonal degeneration, we next tested whether this was associated with any increase in macrophages and other immune cells within the intact nerve. By double labelling for Iba1 and F4/80, we checked macrophage numbers in P7, P21 and P60 control and Sox2HomoOE nerves, and found a significant increase in the numbers of macrophages within these intact Sox2HomoOE nerves at both P21 and P60 (Fig. 8A-G). An increase, although not significant, was also found in numbers of CD3-positive T-cells in intact P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves compared with controls (Fig. S8).

Fig. 8.

Increased numbers of macrophages in intact P60 Sox2HomoOE sciatic nerves. (A-F) Double immunolabelling of P60 control (A-C) and Sox2HomoOE (D-F) sciatic nerves with F4/80 and Iba1 to identify macrophages. Scale bar: 40 µm. Insets in D-F show higher magnification of F4/80/Iba1 double-positive macrophages. (G) Quantification of macrophage numbers at P7, P21 and P60; a significant increase in macrophage numbers is observed in both P21 and P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype at each time point; *P<0.05.

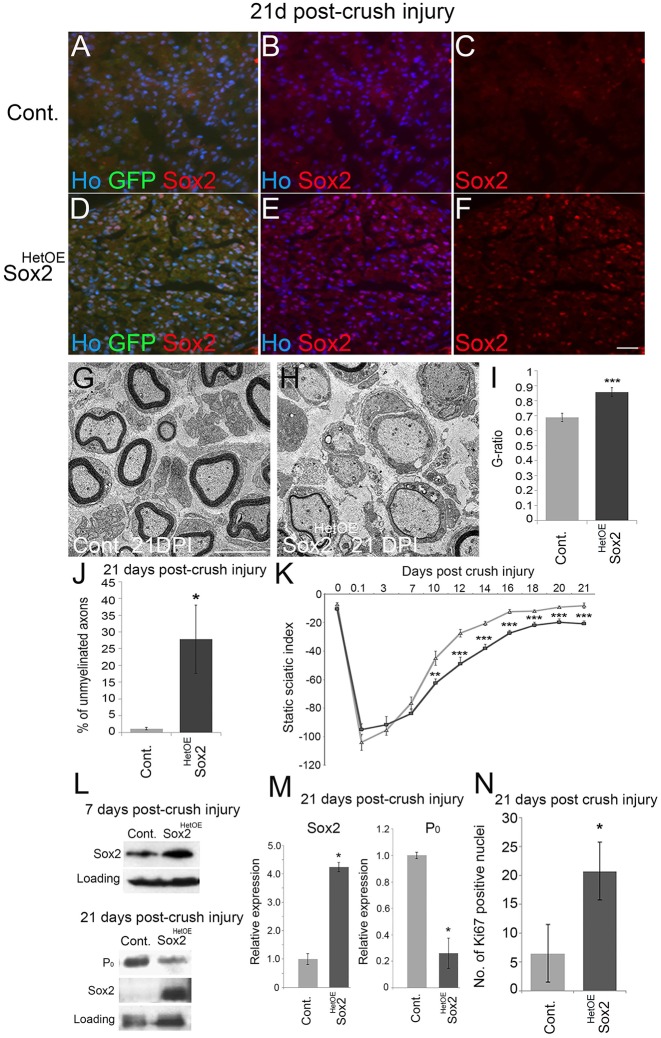

Sox2 over-expression impairs SC remyelination and functional recovery following nerve injury

Although Sox2 re-expression has been shown to drive cell sorting in the nerve bridge following transection injury (Parrinello et al., 2010), it is not known how maintained Sox2 expression in SCs will affect nerve repair and regeneration in the distal nerve following a crush injury. Thus, we next investigated the effect of maintained Sox2 expression on SC re-myelination up to 21 days post-crush injury (DPI). As Sox2HomoOE animals show profound hypomyelination even at P60, we used Sox2HetOE animals for these experiments. As described above, in Sox2HetOE mice, Sox2 and GFP expression begins to decline at P21 and myelination corrects to produce normal nerve morphology and G-ratios at P60; nerve conduction velocity is also unchanged at P90 in these animals (above and Fig. S1I-L).

As we observe transgene expression of both Sox2 and GFP at early developmental timepoints in the Sox2HetOE animals, we hypothesized that following PNS injury the accompanying de-differentiation of SCs distal to the injury site may be sufficient to cause re-activation of transgenic Sox2 and GFP expression in the Sox2HetOE animals, allowing us to study effects of ongoing Sox2 expression in a repairing nerve. This idea proved correct and western blot and immunolabelling showed higher levels of Sox2 induction in Sox2HetOE animals compared with controls at 7 DPI and that Sox2 and GFP expression were maintained at 21 DPI in these animals compared with controls (Fig. 9A-F,L,M). Using TEM, we evaluated SC re-myelination by analysing distal nerve sections from control and Sox2HetOE mice at 21 DPI. Sox2HetOE sciatic nerves distal to the site of injury were hypomyelinated (Fig. 9G,H), with a significantly increased average G-ratio of 0.86±0.028 compared with control nerves, which had an average G-ratio of 0.69±0.028 at this timepoint (Fig. 9I; see Fig. S9A for G-ratio scatter plot). A significant increase in the percentage of unmyelinated axons and a decrease in P0 protein expression were observed in Sox2HetOE mouse nerves at 21 DPI (Fig. 9J,M).

Fig. 9.

Sustained Sox2 expression results in hypomyelination and reduced functional recovery following nerve injury. (A-F) Immunolabelling of distal nerve sections 21 days post-crush injury (DPI) revealed that nerves from control animals no longer expressed Sox2 at this time point (A-C), whereas Sox2 (and GFP) levels remained elevated in the distal sciatic nerves of injured Sox2HetOE mice (D-F). Scale bar: 40 µm. (G,H) TEM pictures of distal nerve sections at 21 DPI revealed that axons in control nerves are remyelinated (G), whereas few axons are remyelinated in Sox2HetOE nerves (H). Scale bar: 5 µm. (I) G-ratio measurements revealed that Sox2HetOE sciatic nerves were significantly hypomyelinated compared with control nerves at 21 DPI. (J) There is a significant increase in the percentage of unmyelinated axons in Sox2HetOE nerves compared with controls at 21 DPI. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype. (K) Quantification of functional recovery by static sciatic index (SSI). Control, n=5; Sox2HetOE, n=7. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test. (L) Western blot showing high levels of Sox2 at 7 and 21 DPI and a reduction in P0 expression in Sox2HetOE mice at 21 DPI. (M) Quantification of western blots from L. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 independent blots. (N) There is significant increase in the number of Ki67-positive nuclei in distal Sox2HetOE sciatic nerves at 21 DPI. Two-sided two-sample Student's t-test; data from n=3 mice of each genotype. *P<0.05, ***P<0.005.

Although numbers of regenerated axons were apparently unchanged, as visualised by neurofilament staining, further analysis of regenerated nerves at 21 DPI did show a significant increase in the axonal diameter of repaired nerves in Sox2HetOE animals compared with controls (Fig. S9B), as well as significantly increased numbers of macrophages still present within the nerve at this timepoint (Fig. S9C-G). No significant difference in macrophage numbers was observed between uninjured nerves from control and Sox2HetOE animals (Fig. S9G).

Having observed that Sox2 overexpression post-injury leads to a marked reduction in SC re-myelination in Sox2HetOE mice following injury, we next tested functional recovery of these animals. Tests of functional recovery using a Static Sciatic Index (SSI) measurement showed that recovery in Sox2HetOE mice was significantly reduced up to 21 DPI compared with control mice (Fig. 9K). This experiment confirmed that, in addition to impairing remyelination, prolonged Sox2 expression in SCs following injury also attenuates functional recovery in these animals.

We next quantified re-myelination by analysing myelin protein re-expression following sciatic nerve injury. Corresponding to TEM analysis (Fig. 9G,H), western blotting confirmed that continued expression of Sox2 in the SCs of Sox2HetOE nerves following injury reduced the re-expression of P0 at 21 DPI in the distal nerve (Fig. 9L,M). Analysis of SC proliferation in Sox2HetOE mice at 21 DPI also showed an ongoing and significantly increased proliferation in the nerve even at this timepoint after injury (Fig. 9N), once more showing the potential for Sox2 to maintain SCs in an undifferentiated and proliferative state in vivo within the nerve.

DISCUSSION

Within SCs, the onset of myelination is controlled by a network of transcription factors that cooperate to ensure a timely and appropriate ensheathment and myelination of axons (Svaren and Meijer, 2008). Mutations in many of these factors, such as those in the zinc-finger protein Krox20 (Egr2), cause hypomyelinating neuropathies in both humans and rodent models (Funalot et al., 2012; Baloh et al., 2009; Desmazieres et al., 2008; Arthur-Farraj et al., 2006; Warner et al., 1999, 1998). Although there are a number of positive transcriptional regulators of myelination in SCs, such as Krox20, Sox10, Nfatc4 and Oct6, an increasing number of negative regulators of myelination, such as MAP kinase signalling through p38 and ERK1/2 pathways, Notch signalling and the transcription factors Pax3 and Jun, have been shown to block the myelination of SCs (Doddrell et al., 2012; Harrisingh et al., 2004; Woodhoo et al., 2009; Napoli et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Parkinson et al., 2004, 2008).

The initial description of Sox2 as an inhibitor of PNS myelination came from the finding that mice with a hypomorphic Krox20 (Egr2) allele (Egr2Lo/Lo), and thus reduced Krox20 expression, showed hypomyelination and increased expression of Sox2 in SCs. Further experiments, which aimed to determine the function of Sox2 as a negative regulator of myelination have used a virally mediated expression system in vitro. These experiments showed that overexpression of Sox2 in vitro prevents both the induction of myelinating SC markers such as Krox20 and P0, and enhanced the proliferation of SCs to the mitogen neuregulin (Le et al., 2005). Although this gives a good indication of Sox2 function, assays of myelination in vitro may not fully reflect the situation in vivo (Lewallen et al., 2011; Golan et al., 2013). Thus, the aim of this study was to fully characterise the effects of maintained Sox2 expression upon both myelination and functional repair within the intact nerves of the PNS in vivo. In addition, this in vivo approach allows us to measure effects of maintained Sox2 expression in SCs upon immune cell influx into the nerve, both following injury and in the intact nerve.

Our experiments show a strong inhibitory effect of Sox2 on the myelination programme of SCs at all timepoints examined. The expression of myelinating SC markers such as Krox20, myelin basic protein and P0 are all reduced, and morphological analysis shows a severe hypomyelination of postnatal nerves. Correspondingly, an analysis of SC-specific Sox2 nulls has shown a slight acceleration of early postnatal myelination (M.D. and X.P.D., unpublished), confirming the inhibitory role of Sox2 in controlling developmental myelination. However, in contrast to experiments with SC-specific Jun and p38αMAP kinase nulls (Parkinson et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2016), we do not observe a function for Sox2 in the downregulation of myelin proteins following injury. Injury experiments in Sox2-null nerves showed a similar profile of myelin protein loss compared with controls (X.P.D., unpublished). Thus, the role of Sox2 appears to be more important in regulating the onset of myelination both during development and following injury, rather than in the events of SC dedifferentiation following axotomy.

An analysis of other potential Sox2 targets showed, both in vitro and in vivo, that Sox2 decreased mRNA and protein levels of the nectin-like protein Necl4 (also known as Cadm4) in SCs (Fig. S10). Inhibition of Necl4 function in SCs, either by shRNA knockdown or expression of a dominant-negative form of the protein, prevents normal SC-axon interaction, Krox20 induction and myelination in vitro (Maurel et al., 2007; Golan et al., 2013; Spiegel et al., 2007), but loss of Necl4 in vivo is associated with focal hypermyelination and a phenotype resembling several CMT subtypes (Golan et al., 2013). It is therefore unclear at present what role, if any, decreased Necl4 levels may play in the phenotype we observe in our Sox2 overexpressing animals.

Overexpression of the mammalian Lin28 homologue B (Lin28B) RNA-binding protein and reduction in the levels of the let-7 family of microRNAs in SCs has been shown to inhibit peripheral nerve myelination in vivo (Gokbuget et al., 2015). As Sox2 has been shown to increase Lin28B levels in embryonic stem cells and neural progenitors (Cimadamore et al., 2013; Marson et al., 2008), we measured Lin28B protein levels in control and Sox2HomoOE nerves at P60. We do not detect Lin28B expression in either control or Sox2HomoOE adult nerve (Fig. S2H); therefore, seemingly eliminating the Lin28B/let-7 signalling axis as mediating the Sox2-induced hypomyelination.

It is still unclear why the expression of the Sox2IRESGFP transgene declines in the Sox2HetOE animals up to P21, as the construct is inserted into the Rosa26 locus and the construct also contains a synthetic cytomegalovirus early enhancer/chicken beta actin (CAG) promoter (Lu et al., 2010); but these issues of silencing of the transgene expression were not seen in the Sox2HomoOE animals, allowing us to monitor the effects of Sox2 expression up to P60 in these animals. Analysis of Sox2HetOE nerves up to P60 allowed us to measure the effects of the removal of Sox2 overexpression in SCs from P21 onwards. In this case, the nerves continued their myelination and by P60 they appeared normally myelinated with G-ratios similar to control nerves, once again underlining a remarkable ability of SCs within the nerve to resume and complete their myelination programme.

The normal myelination observed in P60 Sox2HetOE nerves and re-activation of Sox2 expression following injury in these animals also allowed us to confirm that Sox2 negatively regulates both developmental myelination and re-myelination following injury, in contrast to some regulators within SCs that have developmental or repair-specific functions (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012; Fontana et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2000; Jessen and Mirsky, 2016; Mindos et al., 2017).

Whether negative regulators of myelination play roles in the pathology of human peripheral neuropathies or mouse models of these conditions has been recently examined. Increased expression of the Jun transcription factor in SCs has been observed in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy, and in mouse models of CMT (Saporta et al., 2012; Hutton et al., 2011; Hantke et al., 2014; Klein et al., 2014). Although it has been suggested that abnormal expression of Jun may be involved in the pathology of the hypomyelination seen (Saporta et al., 2012), recent work using the C3 mouse model of CMT1A showed that Jun expression was actually protective. Genetic removal of Jun in the C3 mouse, which models human CMT1A, led to a progressive loss of myelinated sensory axons and increasing sensory-motor loss (Hantke et al., 2014). Thus, as opposed to driving the neuropathy in these animals, raised expression of Jun in SCs is a protective mechanism that ameliorates the disease state. Recent reports have shown that levels of Sox2 mRNA are elevated in mouse models of CMT types 1A and 1B (D'Antonio et al., 2013; Giambonini-Brugnoli et al., 2005), but any potential roles for this increased expression are currently unknown.

The finding of increased macrophage numbers within both the intact Sox2HomoOE nerve at P60 and within the Sox2HetOE nerve following injury suggests a role for Sox2 in the control of macrophage entry to the nerve, although it is not clear whether this is a direct effect, or is due to the lack of myelination or the apparent ongoing myelin breakdown and axonal loss seen in the adult P60 Sox2HomoOE nerves (Fig. 4F,G). In conclusion, we have identified that Sox2 acts as an in vivo inhibitor of the myelinating phenotype of SCs and have shown new roles for this protein in both controlling the proliferation of SCs and recruitment of macrophages to the nerve.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Adenoviruses expressing Krox20/GFP, Sox2/GFP and GFP control have been previously described (Le et al., 2005; Nagarajan et al., 2001; Parkinson et al., 2004, 2008). Antibodies against Sox2 were from Novus Biological (NB 110-37235SS) for western blotting and from Millipore (AB5603) for immunostaining. Antibodies against myelin basic protein (MBP) (sc-13912), β2A tubulin (sc-134229) and α6 integrin (F6) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies to N-cadherin (610920), β-catenin (610163) and Jun (610327) were from Becton-Dickinson. Antibodies to Ki67 (Ab15580) and Sox10 (Ab155279) were from Abcam. Krox20 antibody (PRB-236P) was from Covance. Anti-laminin α2 antibody (ALX-804-190) was from Enzo. Antibodies against myelin protein zero (P0), periaxin, Iba1, F4/80 and CD3 were as described previously (Archelos et al., 1993; Gillespie et al., 1994; Mindos et al., 2017; Napoli et al., 2012). For further details of primary antibodies used, see the supplementary Materials and Methods. Biotinylated antibodies, AlexaFluor fluorescently conjugated antibodies and fluorescently conjugated streptavidin were as previously described (Doddrell et al., 2013).

Transgenic mice and genotyping

Transgenic mouse breeding and experiments were carried out according to Home Office regulations under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Ethical approval for experiments was granted by Plymouth University Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Board. To identify effects of Sox2 overexpression in SCs in vivo, we crossed homozygous Rosa26R-Sox2IRESGFP mice (Lu et al., 2010) with P0-CRE (mP0-TOTACRE) mice (Feltri et al., 1999). This generated heterozygous Rosa26 Sox2IRESGFP CRE-positive (+) and CRE-negative (−) offspring. Heterozygous Rosa26 Sox2IRESGFP CRE+ animals were then backcrossed with homozygous Rosa26 Sox2IRESGFP CRE– mice to generate heterozygous and homozygous Rosa26R-Sox2IRESGFP CRE– and CRE+ mice. CRE+ animals carrying one copy of the Rosa26 Sox2IRESGFP transgene are referred to as Sox2HetOE; CRE+ animals carrying two copies of the Rosa26 Sox2IRESGFP transgene are referred to as Sox2HomoOE mice. For analysis of both Sox2HetOE and Sox2HomoOE mice, age and sex-matched CRE− animals of the same Rosa26 Sox2IRESGFP transgene status are used as controls. For mouse genotyping, genomic DNA was extracted using the HotSHOT method and analysed as previously described (Lu et al., 2010; Feltri et al., 1999; Truett et al., 2000).

Nerve injury

For nerve crush injury, the right sciatic nerve was compressed using round end forceps, as previously described (Dun and Parkinson, 2015). The left sciatic nerve was left uninjured. Mice were euthanized at the indicated time, and both uninjured contralateral and injured distal sciatic nerves collected for analysis.

Cell culture and adenoviral/retroviral infection

Rat SCs were prepared from postnatal day 3 rats, as described previously (Brockes et al., 1979; Parkinson et al., 2001). SCs were infected with GFP/Krox-20 (GFP/K20) (Parkinson et al., 2004; Nagarajan et al., 2001), control GFP or GFP/Sox2 adenovirus (Le et al., 2005) or both GFP/Sox2 and GFP/K20 (Sox2/K20) adenovirus for 24 h in defined medium (DM) (Jessen et al., 1994) then incubated for a further 24 h in DM before fixing and immunolabelling. For details of DRG/Schwann cell culture and co-culture, retroviral/lentiviral constructs and infection, RNA preparation and semi-quantitative PCR, please see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Immunocytochemistry, immunohistochemistry and western blotting

SCs were cultured on poly L-lysine/laminin-coated glass coverslips as previously described (Jessen et al., 1994). For immunohistochemical analysis of sections, nerves were fixed in 4% w/v paraformaldehyde and embedded for cryosectioning. All staining, antibodies, counts and confocal and fluorescence microscopy were as described previously (Doddrell et al., 2013; Parkinson et al., 2008, 2003). Anti-MBP (1:100) and anti-Ki67 (1:200) antibodies were diluted in antibody diluting solution with 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight at 4°C. For western blotting, nerve samples were lysed in SDS buffer and electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Doddrell et al., 2013; Parkinson et al., 2004, 2008, 2003). β2A tubulin was used as loading control for western blots.

Transmission electron microscopy

Nerves were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated and embedded in resin. Semi-thin sections were cut using a glass knife and stained with Toluidine Blue. Ultra-thin sections were cut and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were photographed using a JEOL 1200EX or 1400 TEM microscope. For details of electron microscopy analysis of SC/DRG co-cultures and SCs, see the supplementary Materials and Methods. For quantification of the G ratio in intact and injured nerves, axon diameter and fibre (axon+myelin) diameter were measured from 200 axons from each animal using Image J, which allowed for myelin thickness and G-ratio calculation. For quantification of numbers of myelinated/degenerated fibres per field, average counts were made from five separate fields from both P60 control and Sox2HomoOE nerves.

Functional testing

Motor capacity in 6- and 8-week-old mice was assessed by rotarod analysis. Rotarod training and final testing was as previously described (Saporta et al., 2012; Kuhn et al., 1995). (Rods accelerated from 2 to 30 rotations per minute over 250 s.)

For nerve conduction velocity (NCV) measurements, sciatic nerves from P21 or P90 animals were dissected and placed into a perfusion chamber for 30-45 min before measurements were initiated. During this time the sciatic nerves were incubated at 37°C, and perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) as described previously (Fern et al., 1998; Alix and Fern, 2009). The distal ends of the sciatic nerves were positioned within an aCSF-filled glass stimulating electrode and compound action potentials (CAP) were induced (Alix and Fern, 2009). CAPs were recorded by the second recording aCSF-filled glass electrode surrounding the proximal end of the sciatic nerve (Fern et al., 1998) and displayed using Signal software (Cambridge Electronic Design). NCVs were calculated using two parameters: (1) the length of the stimulated nerve; and (2) the time difference between the start of the stimulus artefact to the peak of the CAP. Measurements of sensory function on control and Sox2HomoOE animals were performed using Von Fray filament and toe pinch tests; for more details see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Functional recovery was measured on mice following injury using the static sciatic index (SSI) measurement. Paw print measurements were taken using a video camera from each mouse before surgery (0 days) and up to 21 days following injury to calculate the SSI (Baptista et al., 2007).

Statistics

For all experiments, n=3 unless otherwise stated. Graphs display the arithmetic mean with error bars representing one standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t-test and P values are used to denote significance: *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P<0.005.

Owing to small sample sizes (n<5 for most comparisons), how well normality and equal variances fitted the data could not be reliably assessed. Sample size was not predetermined by statistical methods and randomisation was not applied. For functional testing using the SSI, the evaluation was made by an individual blinded to the animal genotype. No samples or data were excluded from the analysis. The n value for each experiment is stated in the appropriate figure legend.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for excellent technical support from Mr Peter Bond, Mr Glenn Harper and Dr Roy Moate in the Plymouth University EM Centre and to Ms Cinzia Ferri and Dr Mariacarla Panzeri at the ALEMBIC service at the San Raffaele for help with TEM sample processing and imaging. We thank Prof. Bob Fern, Dr Angelo de Rosa and Mr Sean Doyle (Plymouth University) for help with electrophysiology measurements. We also thank Profs Laura Feltri and Larry Wrabetz (University of New York at Buffalo, USA) for providing the mP0-TOTACRE mice. We are grateful to Mr W. Woznica for excellent technical support with animal husbandry for the study.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: D.B.P., X.P.D., S.L.R., A.C.L.; Methodology: D.B.P., X.P.D., F.F., M.D., S.L.R.; Validation: D.B.P., M.D., S.L.R.; Formal analysis: D.B.P., X.P.D., L.K.D., M.D., S.L.R.; Investigation: D.B.P., X.P.D., R.D.S.D., T.M., L.K.D., F.F., A.Q., M.D., S.L.R.; Resources: D.B.P., X.P.D., M.W.O.; Data curation: D.B.P., X.P.D., R.D.S.D., T.M., L.K.D., S.L.R.; Writing - original draft: D.B.P.; Writing - review & editing: D.B.P., X.P.D., M.D., S.L.R.; Visualization: D.B.P., X.P.D., R.D.S.D., T.M., A.Q., S.L.R.; Supervision: D.B.P., M.D.; Project administration: D.B.P., X.P.D.; Funding acquisition: D.B.P., M.D., A.C.L.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (088228/Z/09/Z to D.B.P.; A.C.L.). M.D. is supported by Fondazione Telethon (GGP14147) and the Italian Ministry of Health (Ministero della Salute) (GR-2011-02346791). Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.150656.supplemental

References

- Alix J. J. P. and Fern R. (2009). Glutamate receptor-mediated ischemic injury of premyelinated central axons. Ann. Neurol. 66, 682-693. 10.1002/ana.21767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archelos J. J., Roggenbuck K., Scheider-Schaulies J., Linington C., Toyka K. V. and Hartung H. P. (1993). Production and kcharacterization of monoclonal antibodies to the extracellular domain of P0. J. Neurosci. Res. 35, 46-53. 10.1002/jnr.490350107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur-Farraj P., Mirsky R., Parkinson D. B. and Jessen K. R. (2006). A double point mutation in the DNA-binding region of Egr2 switches its function from inhibition to induction of proliferation: A potential contribution to the development of congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 24, 159-169. 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur-Farraj P. J., Latouche M., Wilton D. K., Quintes S., Chabrol E., Banerjee A., Woodhoo A., Jenkins B., Rahman M., Turmaine M. et al. (2012). c-Jun reprograms Schwann cells of injured nerves to generate a repair cell essential for regeneration. Neuron 75, 633-647. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh R. H., Strickland A., Ryu E., Le N., Fahrner T., Yang M., Nagarajan R. and Milbrandt J. (2009). Congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy with lethal conduction failure in mice carrying the Egr2 I268N mutation. J. Neurosci. 29, 2312-2321. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2168-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista A. F., Gomes J. R. D. S., Oliveira J. T., Santos S. M. G., Vannier-Santos M. A. and Martinez A. M. B. (2007). A new approach to assess function after sciatic nerve lesion in the mouse – Adaptation of the sciatic static index. J. Neurosci. Methods 161, 259-264. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockes J. P., Fields K. L. and Raff M. C. (1979). Studies on cultured rat Schwann cells. I. Establishment of purified populations from cultures of peripheral nerve. Brain Res. 165, 105-118. 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimadamore F., Amador-Arjona A., Chen C., Huang C. T. and Terskikh A. V. (2013). SOX2-LIN28/let-7 pathway regulates proliferation and neurogenesis in neural precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E3017-E3026. 10.1073/pnas.1220176110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. T., Desai D., Gokina P., Basak S. and Kim H. A. (2008). E-cadherin expression in postnatal Schwann cells is regulated by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase a pathway. Glia 56, 1637-1647. 10.1002/glia.20716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Antonio M., Musner N., Scapin C., Ungaro D., Del Carro U., Ron D., Feltri M. L. and Wrabetz L. (2013). Resetting translational homeostasis restores myelination in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1B mice. J. Exp. Med. 210, 821-838. 10.1084/jem.20122005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmazieres A., Decker L., Vallat J.-M., Charnay P. and Gilardi-Hebenstreit P. (2008). Disruption of Krox20-Nab interaction in the mouse leads to peripheral neuropathy with biphasic evolution. J. Neurosci. 28, 5891-5900. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5187-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doddrell R. D. S., Dun X.-P., Moate R. M., Jessen K. R., Mirsky R. and Parkinson D. B. (2012). Regulation of Schwann cell differentiation and proliferation by the Pax-3 transcription factor. Glia 60, 1269-1278. 10.1002/glia.22346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doddrell R. D. S., Dun X.-P., Shivane A., Feltri M. L., Wrabetz L., Wegner M., Sock E., Hanemann C. O. and Parkinson D. B. (2013). Loss of SOX10 function contributes to the phenotype of human Merlin-null schwannoma cells. Brain 136, 549-563. 10.1093/brain/aws353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun X. P. and Parkinson D. B. (2015). Visualizing peripheral nerve regeneration by whole mount staining. PLoS One 10, e0119168 10.1371/journal.pone.0119168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri M. L., D'Antonio M., Previtali S., Fasolini M., Messing A. and Wrabetz L. (1999). P0-Cre transgenic mice for inactivation of adhesion molecules in Schwann cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 883, 116-123. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fern R., Davis P., Waxman S. G. and Ransom B. R. (1998). Axon conduction and survival in CNS white matter during energy deprivation: a developmental study. J. Neurophysiol. 79, 95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finzsch M., Schreiner S., Kichko T., Reeh P., Tamm E. R., Bösl M. R., Meijer D. and Wegner M. (2010). Sox10 is required for Schwann cell identity and progression beyond the immature Schwann cell stage. J. Cell Biol. 189, 701-712. 10.1083/jcb.200912142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana X., Hristova M., Da Costa C., Patodia S., Thei L., Makwana M., Spencer-Dene B., Latouche M., Mirsky R., Jessen K. R. et al. (2012). c-Jun in Schwann cells promotes axonal regeneration and motoneuron survival via paracrine signaling. J. Cell Biol. 198, 127-141. 10.1083/jcb.201205025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröb F., Bremer M., Finzsch M., Kichko T., Reeh P., Tamm E. R., Charnay P. and Wegner M. (2012). Establishment of myelinating Schwann cells and barrier integrity between central and peripheral nervous systems depend on Sox10. Glia 60, 806-819. 10.1002/glia.22310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funalot B., Topilko P., Arroyo M. A., Sefiani A., Hedley-Whyte E. T., Yoldi M. E., Richard L., Touraille E., Laurichesse M., Khalifa E. et al. (2012). Homozygous deletion of an EGR2 enhancer in congenital amyelinating neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 71, 719-723. 10.1002/ana.23527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gess B., Halfter H., Kleffner I., Monje P., Athauda G., Wood P. M., Young P. and Wanner I. B. (2008). Inhibition of N-cadherin and beta-catenin function reduces axon-induced Schwann cell proliferation. J. Neurosci. Res. 86, 797-812. 10.1002/jnr.21528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giambonini-Brugnoli G., Buchstaller J., Sommer L., Suter U. and Mantei N. (2005). Distinct disease mechanisms in peripheral neuropathies due to altered peripheral myelin protein 22 gene dosage or a Pmp22 point mutation. Neurobiol. Dis. 18, 656-668. 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie C. S., Sherman D. L., Blair G. E. and Brophy P. J. (1994). Periaxin, a novel protein of myelinating schwann cells with a possible role in axonal ensheathment. Neuron 12, 497-508. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90208-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokbuget D., Pereira J. A., Bachofner S., Marchais A., Ciaudo C., Stoffel M., Schulte J. H. and Suter U. (2015). The Lin28/let-7 axis is critical for myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nat. Commun. 6, 8584 10.1038/ncomms9584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan N., Kartvelishvily E., Spiegel I., Salomon D., Sabanay H., Rechav K., Vainshtein A., Frechter S., Maik-Rachline G., Eshed-Eisenbach Y. et al. (2013). Genetic deletion of Cadm4 results in myelin abnormalities resembling Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. J. Neurosci. 33, 10950-10961. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0571-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantke J., Carty L., Wagstaff L. J., Turmaine M., Wilton D. K., Quintes S., Koltzenburg M., Baas F., Mirsky R. and Jessen K. R. (2014). c-Jun activation in Schwann cells protects against loss of sensory axons in inherited neuropathy. Brain 137, 2922-2937. 10.1093/brain/awu257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrisingh M. C., Perez-Nadales E., Parkinson D. B., Malcolm D. S., Mudge A. W. and Lloyd A. C. (2004). The Ras/Raf/ERK signalling pathway drives Schwann cell dedifferentiation. EMBO J. 23, 3061-3071. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton E. J., Carty L., Laura M., Houlden H., Lunn M. P., Brandner S., Mirsky R., Jessen K. and Reilly M. M. (2011). c-Jun expression in human neuropathies: a pilot study. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 16, 295-303. 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00360.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A., Furusho M. and Bansal R. (2013). Sustained activation of ERK1/2 MAPK in oligodendrocytes and schwann cells enhances myelin growth and stimulates oligodendrocyte progenitor expansion. J. Neurosci. 33, 175-186. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4403-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A., Furusho M., Dupree J. L. and Bansal R. (2016). Strength of ERK1/2 MAPK activation determines its effect on myelin and axonal integrity in the adult CNS. J. Neurosci. 36, 6471-6487. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0299-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegle M., Mandemakers W., Broos L., Zwart R., Karis A., Visser P., Grosveld F. and Meijer D. (1996). The POU factor Oct-6 and Schwann cell differentiation. Science 273, 507-510. 10.1126/science.273.5274.507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen K. R. and Mirsky R. (2008). Negative regulation of myelination: relevance for development, injury, and demyelinating disease. Glia 56, 1552-1565. 10.1002/glia.20761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen K. R. and Mirsky R. (2016). The repair Schwann cell and its function in regenerating nerves. J. Physiol. 594, 3521-3531. 10.1113/jp270874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen K. R., Brennan A., Morgan L., Mirsky R., Kent A., Hashimoto Y. and Gavrilovic J. (1994). The Schwann cell precursor and its fate: a study of cell death and differentiation during gliogenesis in rat embryonic nerves. Neuron 12, 509-527. 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90209-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao S. C., Wu H., Xie J., Chang C. P., Ranish J. A., Graef I. A. and Crabtree G. R. (2009). Calcineurin/NFAT signaling is required for neuregulin-regulated Schwann cell differentiation. Science 323, 651-654. 10.1126/science.1166562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. A., Pomeroy S. L., Whoriskey W., Pawlitzky I., Benowitz L. I., Sicinski P., Stiles C. D. and Roberts T. M. (2000). A developmentally regulated switch directs regenerative growth of Schwann cells through cyclin D1. Neuron 26, 405-416. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D., Groh J., Wettmarshausen J. and Martini R. (2014). Nonuniform molecular features of myelinating Schwann cells in models for CMT1: distinct disease patterns are associated with NCAM and c-Jun upregulation. Glia 62, 736-750. 10.1002/glia.22638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn P. L., Petroulakis E., Zazanis G. A. and Mckinnon R. D. (1995). Motor function analysis of myelin mutant mice using a rotarod. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 13, 715-722. 10.1016/0736-5748(96)81215-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le N., Nagarajan R., Wang J. Y., Araki T., Schmidt R. E. and Milbrandt J. (2005). Analysis of congenital hypomyelinating Egr2Lo/Lo nerves identifies Sox2 as an inhibitor of Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2596-2601. 10.1073/pnas.0407836102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewallen K. A., Shen Y. A., De la Torre A. R., Ng B. K., Meijer D. and Chan J. R. (2011). Assessing the role of the cadherin/catenin complex at the Schwann cell-axon interface and in the initiation of myelination. J. Neurosci. 31, 3032-3043. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4345-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Futtner C., Rock J. R., Xu X., Whitworth W., Hogan B. L. and Onaitis M. W. (2010). Evidence that SOX2 overexpression is oncogenic in the lung. PLoS ONE 5, e11022 10.1371/journal.pone.0011022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson A., Levine S. S., Cole M. F., Frampton G. M., Brambrink T., Johnstone S., Guenther M. G., Johnston W. K., Wernig M., Newman J. et al. (2008). Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell 134, 521-533. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel P., Einheber S., Galinska J., Thaker P., Lam I., Rubin M. B., Scherer S. S., Murakami Y., Gutmann D. H. and Salzer J. L. (2007). Nectin-like proteins mediate axon Schwann cell interactions along the internode and are essential for myelination. J. Cell Biol. 178, 861-874. 10.1083/jcb.200705132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindos T., Dun X. P., North K., Doddrell R. D., Schulz A., Edwards P., Russell J., Gray B., Roberts S. L., Shivane A. et al. (2017). Merlin controls the repair capacity of Schwann cells after injury by regulating Hippo/YAP activity. J. Cell Biol. 216, 495-510. 10.1083/jcb.201606052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan R., Svaren J., Le N., Araki T., Watson M. and Milbrandt J. (2001). EGR2 mutations in inherited neuropathies dominant-negatively inhibit myelin gene expression. Neuron 30, 355-368. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00282-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli I., Noon L. A., Ribeiro S., Kerai A. P., Parrinello S., Rosenberg L. H., Collins M. J., Harrisingh M. C., White I. J., Woodhoo A. et al. (2012). A central role for the ERK-signaling pathway in controlling Schwann cell plasticity and peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo. Neuron 73, 729-742. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. B., Dong Z., Bunting H., Whitfield J., Meier C., Marie H., Mirsky R. and Jessen K. R. (2001). Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) mediates schwann cell death in vitro and in vivo: examination of c-Jun activation, interactions with survival signals, and the relationship of TGFβ-mediated death to schwann cell differentiation. J. Neurosci. 21, 8572-8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. B., Dickinson S., Bhaskaran A., Kinsella M. T., Brophy P. J., Sherman D. L., Sharghi-Namini S., Duran Alonso M. B., Mirsky R. and Jessen K. R. (2003). Regulation of the myelin gene periaxin provides evidence for Krox-20-independent myelin-related signalling in Schwann cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 23, 13-27. 10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00024-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. B., Bhaskaran A., Droggiti A., Dickinson S., D'antonio M., Mirsky R. and Jessen K. R. (2004). Krox-20 inhibits Jun-NH2-terminal kinase/c-Jun to control Schwann cell proliferation and death. J. Cell Biol. 164, 385-394. 10.1083/jcb.200307132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson D. B., Bhaskaran A., Arthur-Farraj P., Noon L. A., Woodhoo A., Lloyd A. C., Feltri M. L., Wrabetz L., Behrens A., Mirsky R. et al. (2008). c-Jun is a negative regulator of myelination. J. Cell Biol. 181, 625-637. 10.1083/jcb.200803013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello S., Napoli I., Ribeiro S., Digby P. W., Fedorova M., Parkinson D. B., Doddrell R. D. S., Nakayama M., Adams R. H. and Lloyd A. C. (2010). EphB signaling directs peripheral nerve regeneration through Sox2-dependent Schwann cell sorting. Cell 143, 145-155. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. L., Dun X. P., Dee G., Gray B., Mindos T. and Parkinson D. B. (2016). The role of p38alpha in Schwann cells in regulating peripheral nerve myelination and repair. J. Neurochem. 141, 37-47. 10.1111/jnc.13929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saporta M. A., Shy B. R., Patzko A., Bai Y., Pennuto M., Ferri C., Tinelli E., Saveri P., Kirschner D., Crowther M. et al. (2012). MpzR98C arrests Schwann cell development in a mouse model of early-onset Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1B. Brain 135, 2032-2047. 10.1093/brain/aws140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel I., Adamsky K., Eshed Y., Milo R., Sabanay H., Sarig-Nadir O., Horresh I., Scherer S. S., Rasband M. N. and Peles E. (2007). A central role for Necl4 (SynCAM4) in Schwann cell-axon interaction and myelination. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 861-869. 10.1038/nn1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaren J. and Meijer D. (2008). The molecular machinery of myelin gene transcription in Schwann cells. Glia 56, 1541-1551. 10.1002/glia.20767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topilko P., Schneider-Maunoury S., Levi G., Baron-Van Evercooren A., Chennoufi A. B., Seitanidou T., Babinet C. and Charnay P. (1994). Krox-20 controls myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature 371, 796-799. 10.1038/371796a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truett G. E., Heeger P., Mynatt R. L., Truett A. A., Walker J. A. and Warman M. L. (2000). Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT). BioTechniques 29, 52-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner I. B. and Wood P. M. (2002). N-cadherin mediates axon-aligned process growth and cell-cell interaction in rat Schwann cells. J. Neurosci. 22, 4066-4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner L. E., Mancias P., Butler I. J., Mcdonald C. M., Keppen L., Koob K. G. and Lupski J. R. (1998). Mutations in the early growth response 2 (EGR2) gene are associated with hereditary myelinopathies. Nat. Genet. 18, 382-384. 10.1038/ng0498-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner L. E., Svaren J., Milbrandt J. and Lupski J. R. (1999). Functional consequences of mutations in the early growth response 2 gene (EGR2) correlate with severity of human myelinopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1245-1251. 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner I. B., Guerra N. K., Mahoney J., Kumar A., Wood P. M., Mirsky R. and Jessen K. R. (2006). Role of N-cadherin in Schwann cell precursors of growing nerves. Glia 54, 439-459. 10.1002/glia.20390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhoo A., Alonso M. B., Droggiti A., Turmaine M., D'antonio M., Parkinson D. B., Wilton D. K., Al-Shawi R., Simons P., Shen J. et al. (2009). Notch controls embryonic Schwann cell differentiation, postnatal myelination and adult plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 839-847. 10.1038/nn.2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrabetz L., D'Antonio M., Pennuto M., Dati G., Tinelli E., Fratta P., Previtali S., Imperiale D., Zielasek J., Toyka K. et al. (2006). Different intracellular pathomechanisms produce diverse Myelin Protein Zero neuropathies in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 26, 2358-2368. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3819-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. P., Kim J., Syed N., Tung Y. J., Bhaskaran A., Mindos T., Mirsky R., Jessen K. R., Maurel P., Parkinson D. B. et al. (2012). p38 MAPK activation promotes denervated Schwann cell phenotype and functions as a negative regulator of Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. J. Neurosci. 32, 7158-7168. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5812-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]