Abstract

The eukaryotic B-family DNA polymerases include four members: Polα, Polδ, Polϵ, and Polζ, which share common architectural features, such as the exonuclease/polymerase and C-terminal domains (CTDs) of catalytic subunits bound to indispensable B-subunits, which serve as scaffolds that mediate interactions with other components of the replication machinery. Crystal structures for the B-subunits of Polα and Polδ/Polζ have been reported: the former within the primosome and separately with CTD and the latter with the N-terminal domain of the C-subunit. Here we present the crystal structure of the human Polϵ B-subunit (p59) in complex with CTD of the catalytic subunit (p261C). The structure revealed a well defined electron density for p261C and the phosphodiesterase and oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding domains of p59. However, electron density was missing for the p59 N-terminal domain and for the linker connecting it to the phosphodiesterase domain. Similar to Polα, p261C of Polϵ contains a three-helix bundle in the middle and zinc-binding modules on each side. Intersubunit interactions involving 11 hydrogen bonds and numerous hydrophobic contacts account for stable complex formation with a buried surface area of 3094 Å2. Comparative structural analysis of p59–p261C with the corresponding Polα complex revealed significant differences between the B-subunits and CTDs, as well as their interaction interfaces. The B-subunit of Polδ/Polζ also substantially differs from B-subunits of either Polα or Polϵ. This work provides a structural basis to explain biochemical and genetic data on the importance of B-subunit integrity in replisome function in vivo.

Keywords: crystal structure, DNA replication, human, protein complex, zinc, B-subunit, DNA polymerase epsilon, Dpb2, zinc-binding module

Introduction

In eukaryotes, the bulk of replication is performed by the members of the B-family DNA polymerases Polδ and Polϵ,3 which participate in lagging and leading DNA strand synthesis, respectively (1–3). The other members of this family are Polα and Polζ. Polα extends RNA primers with a short patch of deoxyribonucleotides, and then synthesis is switching to Polδ and Polϵ (4–6). Polζ is one of the key players in replication of damaged DNA (7–9). The common architectural features of all four polymerases are the catalytic subunits with exonuclease/polymerase module(s) and the C-terminal domain (CTD) and the B-subunits (10). Historically, subunits in different organisms were named differently, and the current nomenclature of polymerase subunits is shown in Table 1. The B-subunits stabilize the catalytic subunit (11, 12), act as scaffolding proteins to mediate interactions with other components of the replication machinery (13–16), and regulate DNA-synthesizing activity in a cell cycle-dependent manner, during checkpoints, and telomere maintenance (17–21).

Table 1.

Nomenclature of subunits of B-family DNA polymerases

| Polymerase | Subunit | Protein name |

Alternative names (both organisms) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Yeast | Human | |||

| Primase-Polα | Small of primasea | PRIM1 | Pri1 | p49 | PriS; p48 |

| Large of primase | PRIM2 | Pri2 | p58 | PriL | |

| Aa | POLA1 | Pol1 | p180 | POLA; NSX; Cdc17 | |

| B | POLA2 | Pol12 | p70 | p68 | |

| Polϵ | Aa | POLE1 | Pol2 | p261 | POLE; CRCS12; FILS |

| B | POLE2 | Dpb2 | p59 | DPE2 | |

| Third | POLE3 | Dpb3 | p17 | CHRAC17 | |

| Fourth | POLE4 | Dpb4 | p12 | CHRAC16; YHHQ1 | |

| Polδ | Aa | POLD1 | Pol3 | p125 | Cdc2; MDPL; CRCS10 |

| B | POLD2 | Pol31 | p50 | Cdc1; HYS2 | |

| C | POLD3 | Pol32 | p66 | Cdc27 | |

| Fourth | POLD4 | Cdm1b | p12 | POLDS | |

| Polζ | Aa | REV3L | Rev3 | p353 | POLZ |

| B | POLD3 | Pol31 | p50 | Cdc1; HYS2 | |

| C | POLD4 | Pol32 | p66 | Cdc27 | |

| Small | REV7 | Rev7 | p30 | MAD2L2; MAD2B; FANCV; POLZ2 | |

a Small subunit of primase and A subunits of DNA polymerases contain the catalytic center(s).

b This gene exists in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and its homolog is absent in S. cerevisiae.

Human Polϵ consists of four subunits (Table 1): the catalytic subunit (p261) and the auxiliary subunits (the second subunit, p59, also referred to as the B-subunit, and the third and fourth subunits, p17 and p12, respectively) (10). p261 is a bi-lobe protein comprised of two tandem exonuclease/polymerase domains, the first of which is active, whereas the second is inactive and, along with CTD, plays an essential structural role (16, 22–24). CTD interacts with p59 and has eight conservative cysteines coordinating two zinc ions (25, 26). In yeast, deletion of CTD abolishes interaction between the catalytic and B-subunit and is lethal (23, 27). The integrity of the CTD–B-subunit complex is important for stability of the genome (28, 29). Auxiliary subunits play a regulatory role and guide Polϵ to different biological pathways. The B-subunit integrates Polϵ into the eukaryotic replisome, and in yeast, its N-terminal helical domain is essential for assembly of the Cdc45–MCM–GINS helicase (15). The small subunits p17 and p12 interact with each other through histone-fold motifs similar to those found in histones H2A and H2B (30). As a heterodimer, they bind p261 at the second, inactivated exonuclease/polymerase domain and increase Polϵ affinity to double-stranded DNA (31, 32). Small subunits are not essential for cell growth, but their deletion in yeast destabilizes the replication fork and elevates spontaneous mutagenesis (33).

The crystal structure of the human Polδ B-subunit (p50) in complex with the N-terminal domain of the C-subunit (p66N) provided the first view of the three-dimensional organization of B-subunits (34). The docking surface of Polδ CTD on the B-subunit has been predicted (25) using structural and mutational analyses (34, 35). Moreover, structural and biochemical studies led to a discovery that the CTD of human Polζ is capable of binding the p50–p66 complex of human Polδ in the same manner as the CTD of Polδ (25), meaning that both the Polζ and Polδ catalytic subunits form a complex with p50–p66. These studies led to experiments that confirmed this discovery in yeast (9). The crystal structures of the yeast and human Polα B-subunits in complex with CTDs of the catalytic subunits have also been reported as separate complexes (36, 37), as well as within the human primosome (38). Until now, the structure of the Polϵ B-subunit was the only one unsolved among the human B-family DNA polymerases. Here we report the crystallization, structure determination, and comparative structural analysis of the full-length human Polϵ B-subunit (p59) in complex with the CTD of the catalytic subunit (p261C).

Results

Overall structure of the human Polϵ CTD–B-subunit complex (p59–p261C)

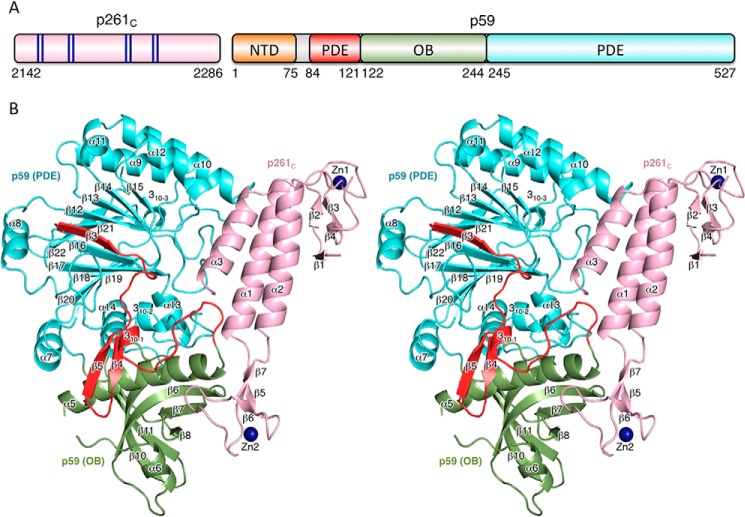

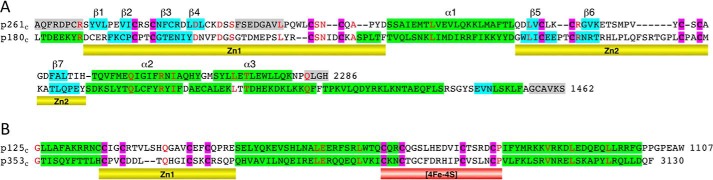

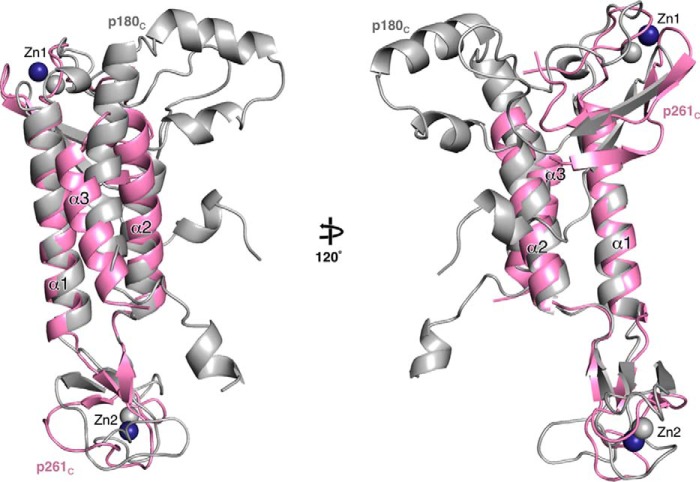

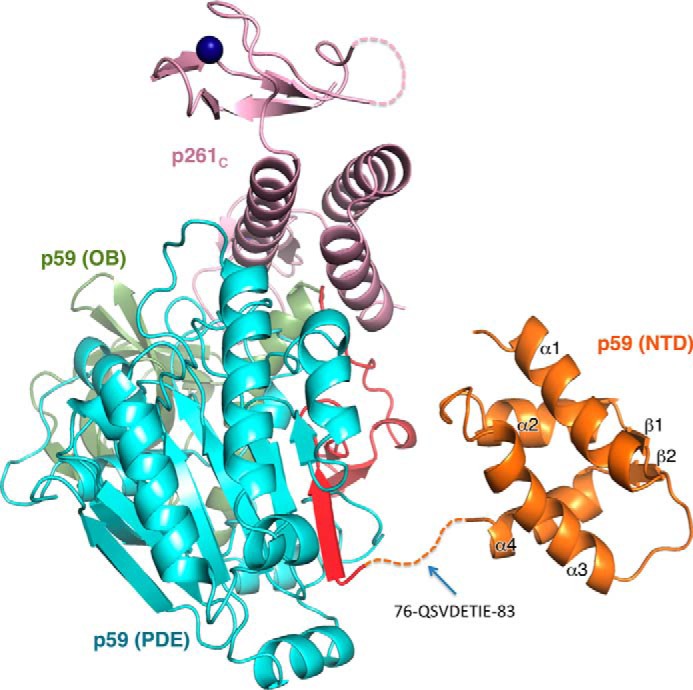

The crystal of the p59–p261C complex contains two independent molecules in an asymmetric unit with root mean square deviations (RMSD) of 0.25 Å for 552 superimposed α-carbons. Each molecule is comprised of p261C (residues 2142–2286) and full-length p59 (residues 1–527) (Fig. 1A). The density was absent for the N-terminal residues 1–83 and for the loop region 146–162 in both p59 subunits, as well as for the N- and C-terminal tails (2142–2149 and 2174–2182) and loop 2283–2286 in both p261C domains. The molecule has a slab-like shape with overall dimensions of 79 Å × 75 Å × 53 Å (Fig. 1B).

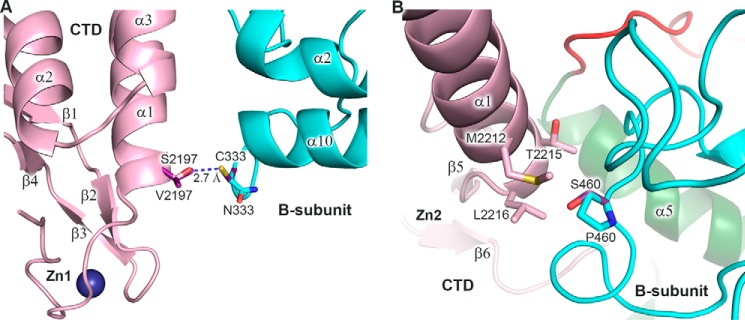

Figure 1.

Overall structure of Polϵ p59–p261C. A, schematic representation of the domain organization. The dark blue lines in the schematics of p261C present the relative positions of the zinc-coordinating residues in two zinc-binding modules: Zn1 (Cys2158, Cys2161, Cys2187, and Cys2190) and Zn2 (Cys2221, Cys2224, Cys2236, and Cys2238). B, stereo view of p59–p261C. p261C is colored light pink; the PDE domain (excluding region 84–121) and OB domain are colored cyan and green, respectively. The N-terminal portion of the PDE domain (residues 84–121) is colored red. Zinc atoms are depicted as dark blue spheres.

C-terminal domain of p261

p261C adopts an elongated asymmetric shape (Fig. 1) with a three-helix bundle (α1, α2, and α3) in the middle and zinc-binding modules (Zn1 and Zn2) on each side, where the highly conserved cysteine residues form the tetrahedral coordination geometries for the zinc ions. Zn1 contains two pairs of antiparallel β-strands: ↑β1↓β4 and ↑β2↓β3. Two zinc-coordinating cysteines, Cys2158 and Cys2161, are from strand β2 and loop β2-β3, respectively. The partially disordered loop β4–α1 provides the remaining two Zn-coordinating cysteines: Cys2187 and Cys2190. The position of Zn1 relative to the three-helix bundle is stabilized by a hydrophobic core formed between helices α1 and α2, strands β1 and β4, and loop β4–α1. The Zn2 module is more compact than Zn1 and contains a small antiparallel β-sheet, ↓β6↑β5↓β7, and two loops: β5–β6 with one zinc-coordinating cysteine, Cys2224; and β6–β7 with two zinc-coordinating cysteines: Cys2236 and Cys2238; remaining Cys2221 is located on the strand β5. Zn2 is connected to the three-helix bundle via two linkers, α1–β5 and β7–α2, but has no additional stabilizing interactions with the rest of p261C.

B-subunit

The p59 subunit is comprised of three domains: an N-terminal domain (NTD), residues 1–75; a phosphodiesterase-like (PDE) domain, residues 84–121 and 245–527; and an oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB) domain, residues 122–244 (Fig. 1). The absence of the density for residues 1–83 in the crystal suggests that the NTD is connected to the rest of the molecule with a flexible linker and lacks the stabilizing interdomain interactions with the PDE, the OB, and p261C. The NMR structure of the NTD revealed a globular four-helical bundle that resembles the C domain of AAA+ proteins (39). Because the residues 1–75 are well folded in solution, the flexible linker connecting the NTD with the rest of p59 should be within residues 76QSVDETIE83 (Fig. 2). The PDE domain is comprised of a central two-layer β-sheet (layer 1, ↑β19↓β20↓β18↓β17↑β16↓β3, and layer 2, ↓β22↑β21↓β12↓β13↓β14↓β15). Helices α7, α13, α14, and 310–2 are flanking layer 1, helices α9–α12 are flanking layer 2, and helix α8 is located on the side of both layers. The PDE is inactive because it lacks the conserved histidine and aspartate residues involved in metal coordination and catalysis. The OB domain contains a β-barrel (↑β6↓β7↑β8β9↑β11↓β10), a helix α5 on the side, and a helix α6 on the bottom of the barrel. The majority of residues in the loop linking helices α5 and α6 are disordered. One of the strands in the barrel is divided by an inserted loop into two strands: β8 and β9. Contrary to the NTD, the PDE and OB domains are well stabilized relative to each other. The interaction between them is dominated by polar contacts with 22 well defined interdomain hydrogen bonds.

Figure 2.

Model of the p59–p261C structure. The model comprised of the crystal structure of p59–p261C and the NMR structure of NTD (Protein Data Bank code 2v6z) (39). The dashed line indicates the linker between NTD and PDE. The domains are colored as in Fig. 1.

Interaction between p59 and p261C

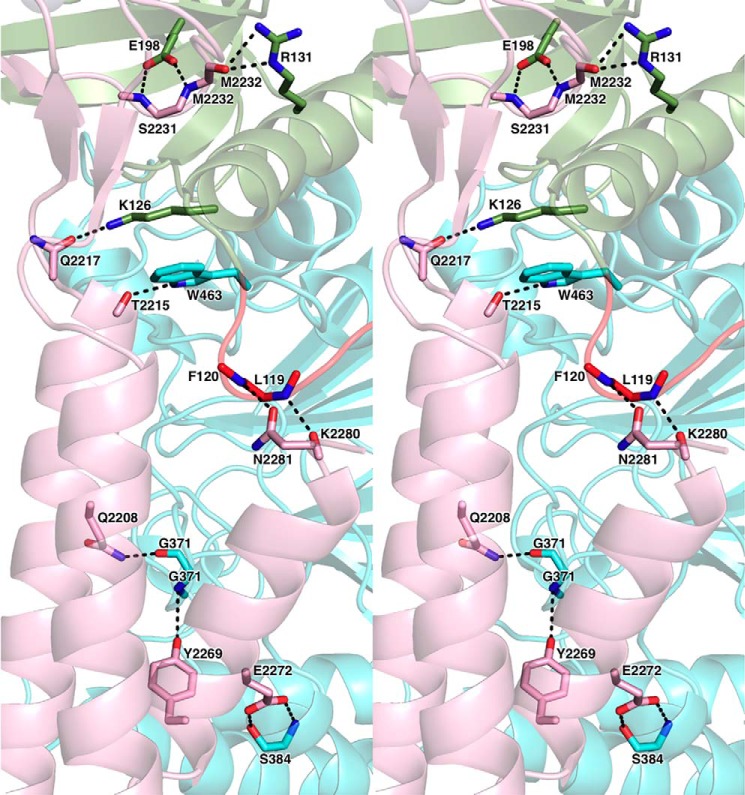

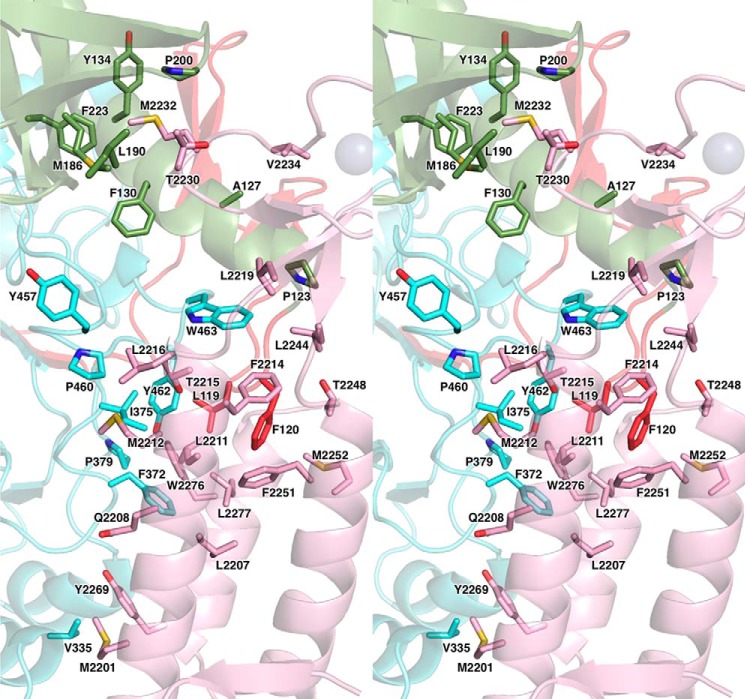

The p59–p261C interface has an elongated shape with complementary surfaces that bury the surface area of 3094 Å2. The subunits are tightly associated by 11 intersubunit hydrogen bonds and by extended hydrophobic areas (Figs. 3 and 4). The N-terminal part of the helix α2 and the entire helices α1 and α3 of the three-helix bundle of p261C interact mainly with the loops of 310–1–α5, β14–α12, and α14–310–2 of the p59 PDE domain. The most prominent feature of this interaction is the wedging of the p59 Phe120 side chain deep into the hydrophobic core of the p261C three-helix bundle (Fig. 4). In addition, the β-sheet and the loop β6-β7 of p261C Zn2 are engaged in interactions with the OB domain of p59, where the p261C Met2232 side chain is inserted into the hydrophobic depression between the helix α5 and the β-barrel of the OB domain. The modular architecture of p261C suggests the possibility of independent folding and p59 binding for Zn2 and the three-helix bundle. This structural feature may explain the effect of small deletions in the yeast ortholog of p261C on its affinity to the B-subunit. It was demonstrated by a two-hybrid assay that partial disruption of either Zn2 or the α-helices weakened intersubunit interaction but did not completely abolish it (27). Only the combined deletion of Zn2 and helices α2 and α3 completely eradicated the association between the catalytic and B-subunits; probably, in this case, the folding of the helix α1, as well as its interaction with the B-subunit were affected in the absence of helices α2 and α3. Unlike Zn2, the Zn1 module does not participate in intersubunit interaction, but it is important for the folding of a three-helix bundle, which explains the defect in cell growth upon partial deletion of Zn1 in CTD of yeast Polϵ (23, 27). In contrast to the Zn2 module and the helical bundle of CTD, the OB and PDE domains of the B-subunit are tightly associated, so a defect in either of these domains will affect the integrity of the other one and should completely abrogate the intersubunit interaction. Consistently, all truncation variants of Dpb2 were unable to interact with the catalytic subunit (40).

Figure 3.

Close-up stereo view of the hydrophilic contacts between p261C and p59. The secondary structure elements are shown with 60% transparency. The domains and carbons are colored according to Fig. 1. The side chains or main chains of the residues involved in intersubunit interactions are shown as sticks. The nitrogens, oxygens, and sulfurs are colored blue, red, and yellow, respectively.

Figure 4.

Close-up stereo view of the hydrophobic contacts between p261C and p59. The presentation details are described in the Fig. 3 legend.

Discussion

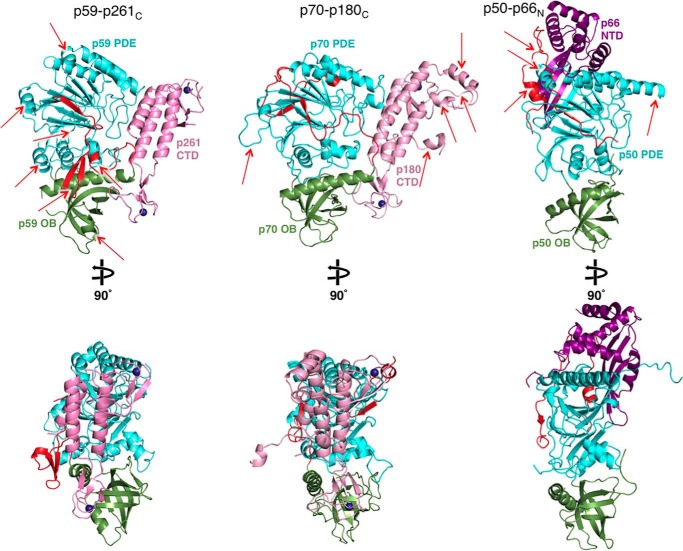

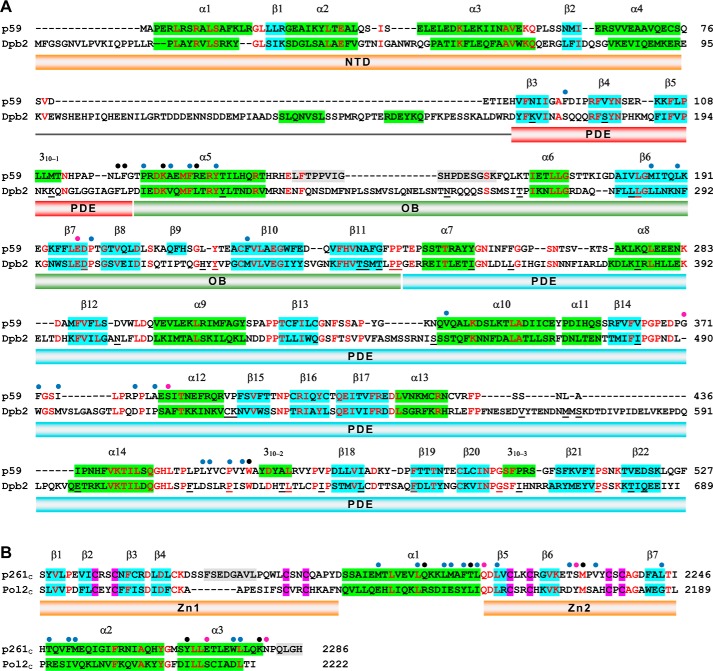

Comparison of the B-subunits of Polα, Polδ, Polϵ, and Polζ

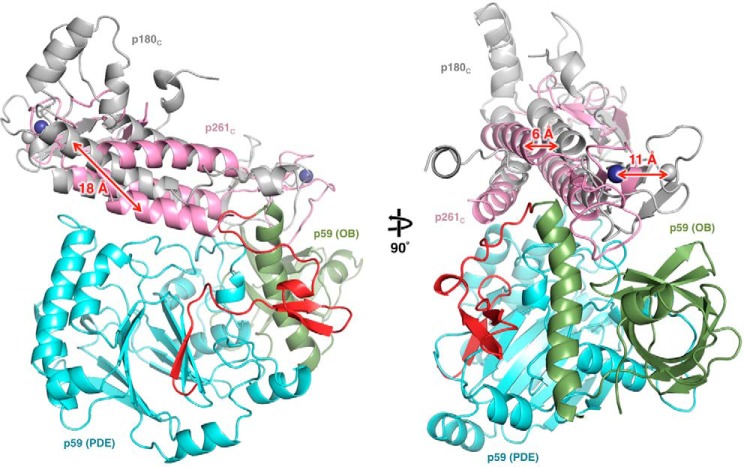

The crystal structures of B-subunit complexes from all human B-family DNA polymerases, including CTDs of catalytic subunits with B-subunits (p70–p180C of Polα and p59–p261C of Polϵ) and the B-subunit with a part of the C-subunit (p50–p66N of Polδ or Polζ), are available now for comparison (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Side-by-side comparison of the Polϵ p59–p261C, Polα p70–p180C, and Polδ/Polζ p50–p66N crystal structures. Red arrows indicate the structural elements contributing to significant differences between the three structures. The coloring of molecules is similar to Fig. 1, except the p66N domain of Polδ/Polζ C-subunit is colored purple. Two different orientations are shown for each molecule. The molecules are displayed using Protein Data Bank entries 5vbn, 5exr, and 3e0j.

The common features of the B-subunits are the presence of a PDE domain with a two-layer β-sheet and an OB domain with a β-barrel, the relative positioning of these two domains, and the surface for docking of the CTD (34, 36, 37). In addition, B-subunits contain some equivalents of helices α3, α4, α5, α9, and α10 (p59 secondary structure nomenclature is used in all comparisons). Despite the conservation of core elements, the B-subunits exhibit significant shifts in the positions of helices and the structures of loops. As a result, the RMSD between p59 and p70 is 2.9 Å2 for 352 matching residues of 427. The similarity between p50 and either p59 (2.9 Å2 for 329 residues) or p70 (3.1 Å2 for 341 residues) is low as well. Among the notable differences between p59 and p70 or p50 are the topologies of residues N- and C-terminal to the OB domain. The β-hairpin β2β3 and helix 310–1 from residues N-terminal to the OB domain, together with helix α7 and coil α7-α8 from residues C-terminal to the OB domain, form a bulky addition on the side of p59 (Fig. 5). This provides p59 a relatively globular shape compared with p70. The bulky addition of p59 is more prominent compared with p50, which also lacks the adjacent helix α8 (Fig. 5). The unique features of p50 are the interaction with p66N and the absence of a globular NTD linked with a PDE domain via a flexible linker in p59 and p70. The docking of p66N is performed mainly by p50 helices α9, α10, an α-helix that is inserted into the loop α9-β13, and the N-terminal residues that are folded as an α-helix, an extended coil, and a small β-strand. In addition, p50 has an elongated strand β22 that interacts with a β-sheet of p66N, resulting in a continuous nine-strand β-sheet (Fig. 5).

Comparison of CTDs

CTDs have significant differences in their size, structure, and sequence. For example, p125C of Polδ and p353C of Polζ are 107 and 100 amino acids (aa) long, respectively, and significantly shorter than p180C (195 aa) of Polα and p261C of Polϵ (144 aa). Both p261C and p180C contain a three-helix bundle with a Zn1 and a Zn2 on either side (Fig. 5). The aa identity between p125C and p353C is 18%, whereas the sequence identities for all other pairs are marginal and comparable with randomly selected sequences. Secondary structure predictions for p125C and p353C show that both contain a short (10-aa) α-helix N-terminal to Zn1 and two longer α helices (28 and 22 aa) (Fig. 6B) that supposedly fulfill the role of α1 and α2 in p261C and p180C (Fig. 6A). In contrast to p180 and p261, p125 and p353 coordinate a [4Fe-4S] cluster at the second metal-binding site of their CTDs (25, 41). Interestingly, two of the [4Fe-4S] coordinating cysteines are predicted to be from the C-terminal portion of helix α2, and both the Zn1 and [4Fe-4S]-binding modules contain short loops (10 aa or less) and no β-strands. Therefore, they acquire a compact structure that is different from the corresponding Zn1 and Zn2 modules of p180C and p261C. At present, only the latter two domains are available for detailed comparison. Their superimposition indicates the conservation of helix α1 and significant differences in the length, conformation, and relative positions of helices α2 and α3 (Fig. 7). The prominent feature of p180C is a longer helix α3 and two helices inserted between the helices α2 and α3 that stabilize an elongated loop in the Zn1. The corresponding loop is disordered in p261C. Additionally, p180C contains a C-terminal extension that forms a β-strand and an α-helix upon interaction with the large subunit of primase (38, 42).

Figure 6.

Structure-based sequence alignments of p261C with p180C (A) and p125C with p353C (B). Blue- and green-shaded boxes depict the α-helices and β-strands, respectively. The gray-shaded boxes indicate the residues that are disordered in the crystal structures of p261C and p180C. The secondary structure elements are from the crystal structures of p261C and p180C (A) and from Phyre (57) predictions for p125C and p353C (B). The conserved residues are highlighted in red. Magenta-shaded boxes depict the zinc-coordinating cysteines. Yellow bars indicate the sequences comprising the zinc-binding modules Zn1 and Zn2. The red bar indicates the sequences implicated in iron–sulfur cluster binding.

Figure 7.

Differences between the Polϵ p261C and Polα p180C structures. The molecules were aligned by superposition of the conservative helices α1 and α2. p261C and p180C are colored light pink and gray, respectively.

Structural insight into the Polϵ p59–p261C subcomplex confirms our previous observation that the Zn2 module of human Polϵ requires zinc for specific docking on p59 (25), which is important for the formation of a stable complex between the catalytic and the B-subunit. It is shown in Ref. 25 that p261C expressed and purified alone contains a substantial level of iron, whereas the pure and stoichiometric p59–p261C complex is iron-free. This indicates that the Zn2 module of p261C is able to coordinate the iron–sulfur cluster, but this prevents specific interaction with p59. According to the structure of [4Fe-4S] cluster-containing proteins, for example, human primase (43), coordination of the cluster by p261C would require the distances between zinc-binding cysteines to be increased by ∼3 Å, which would definitely change the Zn2 structure and result in steric hindrance with the OB domain. These peculiarities explain why an iron–sulfur cluster was seen in partially purified samples of yeast Polϵ and its CTD (41). In contrast to the other B-family DNA polymerases, an additional zinc-binding module is located in the catalytic domain of Polϵ (44), and the iron–sulfur cluster can be misincorporated at this position as well (45). Thus, all structural data support our previous conclusion (25) that Polϵ and Polα require only zinc for correct assembly (5, 44). Moreover, concentrated and very pure samples of human Polα and Polϵ, obtained in our laboratory, were iron-free and fully functional (46, 47), indicating that their operation in eukaryotic cells is not dependent on the iron–sulfur cluster assembly machinery.

Interactions between CTD and the B-subunit

The structures of Polα p70–p180C (36) and Polϵ p59–p261C (Fig. 1B) revealed the common features as well as significant differences in the mode of intersubunit interactions. In both molecules, Zn2 mainly interacts with the OB domain, whereas the helical bundle of CTD associates with the PDE domain of the B-subunit. In both cases, the contact area between Zn2 and the B-subunit composes ∼30% of the total interaction interface between the two subunits. With regard to the differences, it is worth noting the predominance of hydrophobic contacts at the CTD–B-subunit interaction interface and the reduction of the buried surface area by 30% in the case of Polϵ (Figs. 3 and 4). Superimposition of the B-subunits in p70–p180C and p59–p261C shows a significant shift in position of p261C relative to p180C with an average displacement of their central three-helix bundles exceeding 6 Å (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Comparison of CTD docking on the B-subunit between p59–p261C and p70–p180C. Both CTD–B-subunit complexes were aligned by superposition of the B-subunits; p70 is omitted for clarity. The p59–p261C domains are colored according to Fig. 1, and p180C is colored gray.

The structure of p50 with either p125C of Polδ or p353C of Polζ has not been reported yet. The mapping of the p50 surface area responsible for the docking of p125C was performed with data obtained for the fission yeast ortholog using random and directed mutagenesis techniques (35). This revealed that the p50 residues responsible for p125C interaction are disordered. It was proposed and confirmed that disordered loops provide the ability of p50 to adopt the binding of both p125C and p353C despite their low amino acid sequence identity (25). Unlike p50, p70 of Polα and p59 of Polϵ accept only one CTD: p180C or p261C, respectively.

The p59–p261C structure helps to explain phenotypes of the yeast Dpb2 mutants

A set of temperature-sensitive Dpb2 alleles was previously generated by using direct and random mutagenesis techniques (Table 2). Some Dpb2 mutants exhibited a mutator phenotype comparable to that of mismatch-repair-defective strains (msh6), indicating that defects in the B-subunit of the human Polϵ gene can induce genomic instability. The structure of p59–p261C provides a rationale for explanation of the effects of amino acid changes in the yeast Polϵ B-subunit, characterized by weakened interaction with the catalytic subunit and the GINS complex, elevated spontaneous mutagenesis, and the affected Nrm1 branch of the DNA replication checkpoint (11, 21, 28, 29, 40, 48).

Table 2.

Correlation between predicted effect on protein integrity and phenotypes of Dpb2 mutants

The data for cell growth, mutability, and interaction between the catalytic and B-subunits of yeast Polϵ were obtained from Refs. 11, 28, and 40. Amino acid changes resulting in steric hindrance are indicated by an asterisk. Mutations resulting in hydrophobic pocket disturbance caused by hydrophobic amino acid replacement by a charged or significantly smaller residue are shown in bold type. p59 residues near the intersubunit interaction interface (when the distance to the closest p261C residue is <10 Å) are underlined; p59 resides at the interaction interface are underlined and italicized. It was assumed that mutations resulting in steric hindrance or affecting a hydrophobic pocket have a moderate effect on B subunit integrity; otherwise, they have a minor effect.

| Dpb2 allelea | Amino acid substitutions in Dpb2 (homologous amino acid of p59 is in parenthesis) | Cell growth at 37 °Cb | Pol2 bindingc | Mutability increase at CanRd | Integrity losse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||||

| 1 | D300 (D199)N, K521 (P394)R, V565 (L435)F*, G662 (G500)R* | +f | 17 | (2.4)g | ++ |

| 100 | L284 (V183)P*, T345 (G241)A | − | 0.6 | 7 (5.4) | ++ |

| 101 | L284 (V183)P* | ± | 83 | 4 (2.6) | ++ |

| 102 | T345 (G241)A | + | 106 | (1.4) | + |

| 103 | T342 (N238)I, S343 (A239)F, T345 (G241)I, P347 (P243)S, P348 (P244)S | − | 53 | 5 (5.2) | ++ |

| 104 | I484 (V364)S, L630 (L469)S, F649 (F487)C | − | 15 | 3 | ++ |

| 107 | K171 (N87)E, S182 (V98)P*, L284 (V183)P*, I385 (K276)T, M572 (L435)V, S574 (A436)T | − | 5 | 7 | ++ |

| 108 | T269 (K166)A, H318 (L217)R*, Y320 (Y218)S, I359 (Y255)V, T629 (A468)A, I635 (V474)V | − | 47 | 2 | ++ |

| 109 | K197 (M111)M, N258 (H155)S, S453 (N333)C, C520 (V393)L*, F615 (L454)S | ± | 27 | 2 | ++ |

| 110 | L285 (L184)W*, L365 (F261)S, N405 (D292)I*, M572 (L435)K | − | 3 | 4 | ++ |

| 111 | Y223 (T135)H | + | 103 | 1.3 | + |

| 112 | E598 (I437)D, P621 (P460)S, L641 (I480)H*, I665 (P503)V, T682 (V519)A | − | 2 | 7 | ++ |

| 113 | K171 (N87)E, S182 (V98)P*, L284 (V183)P* | − | 0.7 | 8 | ++ |

a Alleles dpb2-105 and dpb2-106 containing more than 11 mutations are not listed.

b Normal and slow cell growth at elevated temperature is designated as + and ±, respectively; − indicates very slow or no cell growth.

c Binding experiments were conducted using the yeast two-hybrid system; β-galactosidase activity measured at 23 °C was taken for 100% in the case of a wild-type protein.

d The frequency of forward mutations was measured at the CAN1 locus (the numbers indicate the fold increase compared with a wild-type protein); the DPB2 variants were integrated into the DPB2 chromosomal locus (ΔI(-2)I-7BYUNI300).

e Integrity loss is a degree of fold disturbance defined as minor (+) or moderate (++).

f In one study, cells demonstrated normal growth at 37 °C when the allele dpb2-1 was located on a centromeric plasmid, but the authors were unable to obtain viable integrants of this allele on the chromosome (28). In an earlier study, cells with a chromosomal copy of dpb2-1 stopped division within 4 h after a temperature shift up to 38 °C and exhibited slow growth even at 24 °C (11).

g The values in parentheses are obtained from experiments where DPB2 variants are located on a centromeric plasmid.

High secondary structure conservation between p59–p261C and its yeast ortholog (Fig. 9) implies similar three-dimensional organization, allowing for mapping the residues changed in Dpb2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the structure of p59 and for predicting the effect of these mutations on the integrity of Dpb2 and its interaction with the catalytic subunit (Table 2). Structural analysis of 38 mutations revealed that two residues, Ser453 and Pro621, are located at the CTD–B-subunit interface. According to modeling, Asn333 of p59, which corresponds to Ser453 of Dpb2, is located at the edge of the intersubunit interface and does not participate in the interaction with p261C (Fig. 10A); there is also low probability that the hydroxyl of Dpb2 Ser453 makes a hydrogen bond with any surrounding residue. It is likely that the appearance of a cysteine at this position does not affect the B-subunit folding in yeast and human Polϵ but can result in moderate steric hindrance with Val2140 of Pol2C, which corresponds to Ser2197 of p261C (Fig. 9B). In the case of the Dpb2-112 mutant, Pro460 of p59, which corresponds to Pro621 of Dpb2, participates in hydrophobic interactions with three amino acids of p261C: Met2212, Thr2215, and Leu2216 (Fig. 10B), which correspond to Glu2155, Leu2158, and Ile2159 of Pol2C, respectively (Fig. 9B). Therefore, the replacement of proline by serine at this position affects the hydrophobic pocket at the CTD–B-subunit interface. Pro460 also plays a structural role for the coil α14–310–2, and its substitution may affect the position of amino acids Leu456, Tyr457, Tyr462, and Trp463, which interact with p261C (Fig. 9A). Thus, P621S substitution should have stronger effect on intersubunit interaction than S453C, which is well correlated with more pronounced effects on viability, affinity to Pol2, and spontaneous mutagenesis in cells expressing Dpb2-112 mutant versus Dpb2-109 (Table 2). Interestingly, several other Dpb2 mutants do not have amino acid substitutions, which can directly affect the association with a catalytic subunit, but some of them have a phenotype similar to the Dpb2-112 mutant (Table 2). It is likely that Dpb2 folding is affected in these mutants. All temperature-sensitive mutants listed in Table 2 have a minor to moderate effect on B-subunit integrity. Two alleles with predicted minor effect on Dpb2 folding (dpb2-102 and dpb2-111) have phenotypes close to the wild type.

Figure 9.

Structure-based sequence alignments of the B-subunits (A) and CTDs (B) of human and yeast Polϵ. The α-helices and β-strands are depicted by green- and blue-shaded boxes, respectively. The gray-shaded boxes indicate the residues that are disordered in the crystal structure of p59–p261C. The conserved residues are shown in red. The blue, pink, and black circles indicate amino acids involved in intersubunit hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and both types of interactions, respectively. The Dpb2 residues listed in Table 2 are underlined. The fold prediction for the yeast Polϵ subunits was performed using Phyre (57).

Figure 10.

Modeling of the amino acid changes mapped to the intersubunit interface. A, modeling of p59 Cys333 and p261C Val2197 in place of asparagine and serine, respectively. Only one conformation of Cys333 is allowed to avoid steric hindrance with main-chain atoms. In both allowed conformations of Val2197 (only one is shown for clarity), there is a clash with Cys333. B, modeling of p59 Ser460 in place of proline. The p59–p261C domains are colored according to Fig. 1. Carbons of the modeled residues are colored purple. A blue dashed line depicts the distance between atoms. Zn1 and Zn2 labels show the position of corresponding zinc-binding modules.

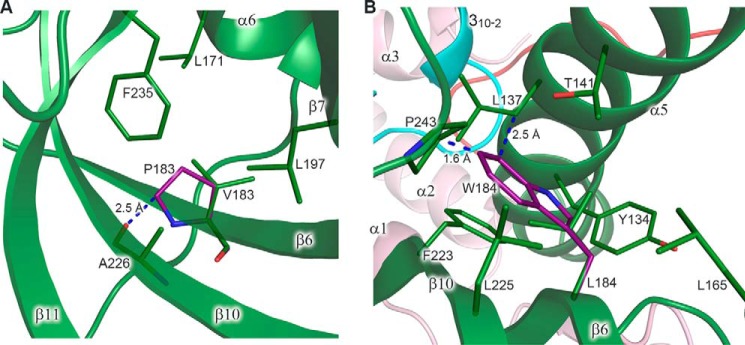

We propose that mutations affecting hydrophobic pockets or resulting in steric hindrance can lead to local disturbance of the protein fold, and the effect on association of subunits should be stronger as the distance between the mutated residue and the interaction interface becomes shorter. The exact effect of amino acid substitution on the Dpb2 structure depends on many factors, such as location, involvement in interactions with other residues, degree of steric hindrance, and how the molecule can tolerate this change. The contribution of some of these factors, as well as the cumulative effect of several mutations on Dpb2 integrity, is difficult to estimate accurately, especially from the structure of a homologous but diverged protein. Despite these complications, it was possible to make unambiguous structural predictions for several Dbp2 mutants. For example, the Dpb2-113 mutant has a strongest mutator effect coinciding with disrupted binding to the catalytic subunit (Table 2). This mutant has substitution of two residues located on β4 and β6 strands to proline, which results in steric hindrance with a main-chain oxygen of an amino acid located on the neighbor strand. For example, Val183 of p59, corresponding to Leu284 of Dpb2, is located in the hydrophobic pocket inside of the β-barrel of the OB domain (Fig. 11A). Steric hindrance between proline in this position and Ala226 will result in disruption of at least two hydrogen bonds and local disturbance of the β-barrel nearby the CTD–B-subunit interface. These two proline substitutions in the Dpb2-113 mutant have an additive effect, because the Dpb2-101 mutant with only one proline substitution shows mild phenotype (Table 2). It is likely that only these two proline substitutions define the phenotype of the Dpb2-107 mutant, which has four additional mutations with predicted minor effects on protein integrity. The other allele with a severe defect in intersubunit association is a dpb2-110, which has three mutations with a predicted moderate effect on the protein fold. Probably, the L285W change is the main determinant of the phenotype of this allele. The conservative Leu285 is located inside of a hydrophobic pocket between the α-helix and the β-barrel of the OB domain, close to the intersubunit interface. Modeling of a bulky tryptophan at this position reveals strong steric hindrance with surrounding hydrophobic residues, which will disturb the OB domain, as well as its interaction with the PDE domain and CTD (Fig. 11B).

Figure 11.

Modeling of the amino acid changes inducing steric hindrance. A, close-up view of a hydrophobic pocket with modeled proline in place of Val183. Val183 makes two main-chain–to–main-chain hydrogen bonds with Ala226 (not shown). Leu171, Val183, Leu197, Ala226, and Phe235 of p59 correspond to Leu274, Leu284, Leu298, Val328, and Phe339 of Dpb2, respectively. B, close-up view of a hydrophobic pocket with modeled tryptophan in place of Leu184. In the shown conformation, tryptophan clashes with the side chains of Pro243 and Leu137. Tyr134, Leu137, Thr141, Leu165, Leu184, Phe223, Leu225, and Pro243 of p59 correspond to Tyr222, Thr225, Val229, Ile268, Leu285, Met325, Leu327, and Pro347 of Dpb2, respectively. p59 and p261C are colored according to Fig. 1. Carbons of the modeled residues are colored purple. The residues are shown as sticks. The secondary structure elements are shown with 20% transparency. Blue dashed lines depict the closest distance between the residues. Proline and tryptophan rotamers, shown in A and B, respectively, correspond to minimal steric hindrance.

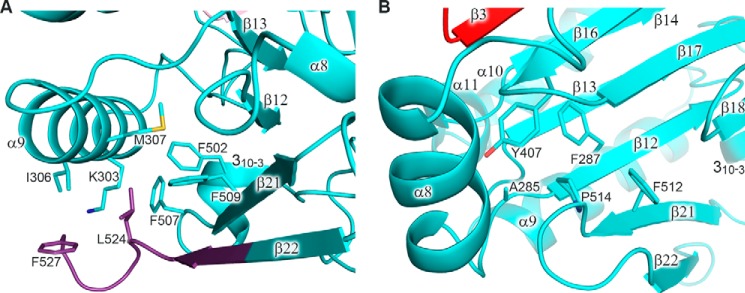

The most interesting example of the influence of B-subunit integrity on the replisome function in vivo is a dpb2-200 mutation, which results in lethality at all temperatures and corresponds to deletion of the last six residues (QEEIYI) from the C terminus of the yeast Polϵ B-subunit and to substitution of conservative Pro677 by serine (49). Mapping of these mutations on the p59 structure led to the conclusion that this change induces severe destabilization of the protein fold (Figs. 9A and 12). The C-terminal deletion disrupts the last β-strand, which is a part of a central two-layer β-sheet of the PDE domain. Moreover, Pro514 and Leu524 of p59, which correspond to Pro677 and Ile687 of Dpb2, participate in the formation of two hydrophobic pockets tethering different parts of the PDE domain (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Analysis of the role of Pro514 and the extreme C-terminal region on p59 folding. A, close-up view of a hydrophobic pocket containing Leu524 and Phe527. The carbons of p59 residues corresponding to the deleted region in the Dpb2-200 mutant are colored purple. Lys303, Ile306, Met307, Phe502, Phe507, and Phe509 of p59 correspond to Ala416, Lys419, Ile420, Phe664, Ala670, and Tyr672 of Dpb2, respectively. B, close-up view of a hydrophobic pocket containing Pro514. Ala285, Phe287, Tyr407, and Phe512 of p59 correspond to His397, Phe399, Tyr534, and Tyr675 of Dpb2, respectively. The p59 domains are colored according to Fig. 1. Side chains of the residues are shown as sticks.

These observations support the idea that the effect of Dpb2 mutations on genomic stability is due to disturbance of replication initiation and elongation because of affected polymerase integrity and tethering to the replisome (29). Indeed, mutations of Psf1, which is a component of the GINS complex and interacts with NTD of the Polϵ B-subunit, also increase spontaneous mutagenesis (48). Probably, in Dbp2 mutants with compromised binding to the catalytic subunit, NTD is folded correctly and supports CMG assembling (15) if solubility of the B-subunit and its transport to the nucleus are not significantly affected.

Conclusions

The B-subunits of B-family DNA polymerases have evolved as the hubs for a variety of regulatory protein-protein interactions. The analysis of their crystal structures helps to evaluate the possible mechanisms for the involvement of such hubs during various stages of DNA replication. Recent cryo-EM structure of the yeast CMG-Polϵ-Ctf4-Polα complex indicates that Polϵ interacts directly with the CMG helicase, whereas Polα is located at a distance from the CMG and has more mobility (50). Contrary to the short NTD-PDE linker in human Polϵ, the corresponding linker in human and yeast Polα can be extended to >200 Å, enabling the primosome to reach the priming sites on both the lagging strand and distantly located leading strand (51). Although the role of p70 NTD in Polα tethering to the replisome has not been ascertained thus far, the potential replisome-anchoring site on the N terminus of the catalytic subunit is connected with the rest of the molecule by a 190-aa linker (5). The NTD-PDE linker in Dpb2 is longer than in p59, but it might be structured and compact, because secondary structure prediction shows the presence of two α-helices (Fig. 9A).

The crystal structure of p59–p261C as provided here is the first high-resolution three-dimensional view of the Polϵ CTD–B-subunit complex. Together with the structure of the polymerase/exonuclease domain of a yeast ortholog (44), this is the only high-resolution structural information for eukaryotic Polϵ available to date. The structures of small subunits (p17, p12) and a catalytically inactive polymerase domain between the catalytic core and p261C are required to build an accurate model of the whole four-subunit complex including the data from electron microscopy studies of Polϵ or its complex with CMG. Unfortunately, the current resolution of electron microscopy data for Polϵ is not sufficient for unambiguous docking of the better-resolved crystal structures of its parts (16, 24, 50). Further research will be required to evaluate the function of p59 and to find the exact position of p59–p261C relative to the catalytic core and other domains of Polϵ in the replicating complex. It will also be interesting to see the detailed mechanism of p59–p261C participation in recruitment of Polϵ to the CMG helicase.

Experimental procedures

Protein expression and purification

Cloning, expression, and purification to homogeneity of the full-length human Polϵ B-subunit (p59; residues 1–527) in complex with the C-terminal domain of the catalytic subunit (p261C; residues 2142–2286) have been described elsewhere (25). The peak fractions were combined and concentrated to 11 mg ml−1 in buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, and 1 mm DTT. The concentrated protein solution was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 193 K until use.

Crystallization

The aliquots of protein solution were defrosted and centrifuged, and the absence of aggregation was verified with dynamic light scattering. Initial crystallization screening was performed by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 295 K by mixing 1 μl of protein solution with 1 μl of reservoir solution. The reservoirs contained 2-fold diluted Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 (Hampton Research) solutions with the addition of 2 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, pH 7.5. Clusters of crystals appeared in the 32nd condition of Crystal Screen. The optimized reservoir solution with 50 mm sodium citrate, pH 5.6, 0.70 m ammonium sulfate, and 2 mm Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine resulted in well shaped single crystals (Fig. 13) growing at 295 K in 3–5 days.

Figure 13.

Photomicrograph of the p59–p261C crystal.

Data collection

For diffraction data collection, the crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant solution (50 mm sodium citrate, pH 5.6, 1 m ammonium sulfate, and 32% (v/v) glycerol) for a few seconds, scooped in a nylon-fiber loop, and flash-cooled in a dry nitrogen stream at 100 K. Diffraction data sets were collected using synchrotron X-rays on the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon source beamline 24ID-C equipped with a Pilatus 6M detector. All intensity data were indexed, integrated, and scaled with DENZO and SCALEPACK from the HKL-2000 program package (52). The crystals belong to tetragonal space group P21212 and diffract up to 2.35 Å resolution. The crystal parameters and data processing statistics of the best data set are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P21212 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | |

| a, b, c | 92.26, 201.46, 78.34 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.35 (2.39–2.35)a |

| Rmerge | 0.072 (0.481) |

| I/σI | 21.5 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.6 (98.2) |

| Unique reflections | 61,804 (3044) |

| Redundancy | 3.3 (3.1) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.75–2.35 (2.5–2.35) |

| No. reflections | 58,410 (8677) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.225/0.264 (0.329/0.374) |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 8829 |

| Ligand/ion | 14 |

| Water | 212 |

| Mean B-factors (Å2) | 46.0 |

| R. M. S. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.5 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Core | 87.7 |

| Allowed | 11.0 |

| Generously allowed | 1.3 |

| Disallowed | 0 |

a The numbers in parentheses refer to the highest-resolution shell.

Crystal structure determination

The crystal structure of the p59–p261C complex was determined by the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion method. The positions of four zinc ions were located from anomalous difference Patterson maps, indicating the presence of two independent p59–p261C molecules in asymmetric unit. Initial automated model building performed with Phenix (53) revealed about 65% of correctly built structure. The rest of the crystallographic computing was performed with CNS version 1.1 (54) using phases from the automatically built partial model. Non-crystallographic symmetry restraints and density modification with 2-fold averaging were applied during the initial stages of model refinement and map calculations for manual model building with Turbo-Frodo. Application of zonal scaling (55) slightly improved the quality of the electron density maps. After the addition of solvent molecules, the model was refined to an Rcryst of 22.2% and an Rfree of 26.28% at the highest resolution of 2.35 Å. The final refinement statistics are provided in Table 3. The figures containing molecular structures were prepared using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (version 1.8; Schrödinger) (56); amino acids were modified using the mutagenesis tool and the library of backbone-dependent rotamers included in this software.

Author contributions

A. G. B. and J. G. expressed and purified the p59–p261C complex. N. D. B. and J. G. crystallized the complex. I. K., N. D. B., and T. H. T. collected the diffraction data. Y. I. P. analyzed genetic data. T. H. T. initiated the project and determined the crystal structure. T. H. T. and A. G. B. wrote the manuscript, with contributions and critical comments from the other authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Jordan for editing of this manuscript. The Eppley Institute's X-ray Crystallography Core Facility is supported by Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA036727. This work is also based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) beamline at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory, which is supported by NIGMS, National Institutes of Health Grant P41 GM103403. The Pilatus 6M detector on the 24-ID-C Beamline is funded by National Institutes of Health High-End Instrumentation Grant S10 RR029205 from the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This work was supported by NIGMS, National Institutes of Health Grant GM101167 (to T. H. T.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 5vbn) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- Pol

- DNA polymerase

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- OB

- oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding domain

- PDE

- phosphodiesterase domain

- aa

- amino acid

- CMG

- Cdc45–Mcm–GINS

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation.

References

- 1. Nick McElhinny S. A., Gordenin D. A., Stith C. M., Burgers P. M., and Kunkel T. A. (2008) Division of labor at the eukaryotic replication fork. Mol. Cell 30, 137–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pavlov Y. I., and Shcherbakova P. V. (2010) DNA polymerases at the eukaryotic fork-20 years later. Mutat. Res. 685, 45–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burgers P. M., and Kunkel T. A. (2017) Eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 417–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pellegrini L. (2012) The Pol alpha-primase complex. Subcell. Biochem. 62, 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baranovskiy A. G., and Tahirov T. H. (2017) Elaborated action of the human primosome. Genes (Basel) 8, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muzi-Falconi M., Giannattasio M., Foiani M., and Plevani P. (2003) The DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex: multiple functions and interactions. ScientificWorldJournal 3, 21–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawrence C. W. (2004) Cellular functions of DNA polymerase zeta and Rev1 protein. Adv. Protein Chem. 69, 167–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gan G. N., Wittschieben J. P., Wittschieben B. O., and Wood R. D. (2008) DNA polymerase zeta (pol zeta) in higher eukaryotes. Cell Res. 18, 174–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Makarova A. V., and Burgers P. M. (2015) Eukaryotic DNA polymerase zeta. DNA Repair (Amst.) 29, 47–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johansson E., and Macneill S. A. (2010) The eukaryotic replicative DNA polymerases take shape. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Araki H., Hamatake R. K., Johnston L. H., and Sugino A. (1991) DPB2, the gene encoding DNA polymerase II subunit B, is required for chromosome replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 4601–4605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou J. Q., He H., Tan C. K., Downey K. M., and So A. G. (1997) The small subunit is required for functional interaction of DNA polymerase delta with the proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1094–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uchiyama M., and Wang T. S. (2004) The B-subunit of DNA polymerase alpha-primase associates with the origin recognition complex for initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7419–7434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou B., Arnett D. R., Yu X., Brewster A., Sowd G. A., Xie C. L., Vila S., Gai D., Fanning E., and Chen X. S. (2012) Structural basis for the interaction of a hexameric replicative helicase with the regulatory subunit of human DNA polymerase alpha-primase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26854–26866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sengupta S., van Deursen F., de Piccoli G., and Labib K. (2013) Dpb2 integrates the leading-strand DNA polymerase into the eukaryotic replisome. Curr. Biol. 23, 543–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou J. C., Janska A., Goswami P., Renault L., Abid Ali F., Kotecha A., Diffley J. F. X., and Costa A. (2017) CMG-Pol epsilon dynamics suggests a mechanism for the establishment of leading-strand synthesis in the eukaryotic replisome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 4141–4146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nasheuer H. P., Moore A., Wahl A. F., and Wang T. S. (1991) Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of human DNA polymerase alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 7893–7903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foiani M., Liberi G., Lucchini G., and Plevani P. (1995) Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the yeast DNA polymerase alpha-primase B subunit. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 883–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grossi S., Puglisi A., Dmitriev P. V., Lopes M., and Shore D. (2004) Pol12, the B subunit of DNA polymerase alpha, functions in both telomere capping and length regulation. Genes Dev. 18, 992–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kesti T., McDonald W. H., Yates J. R. 3rd, and Wittenberg C. (2004) Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the DNA polymerase epsilon subunit, Dpb2, by the Cdc28 cyclin-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14245–14255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dmowski M., Rudzka J., Campbell J. L., Jonczyk P., and Fijalkowska I. J. (2017) Mutations in the non-catalytic subunit Dpb2 of DNA polymerase epsilon affect the Nrm1 branch of the DNA replication checkpoint. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tahirov T. H., Makarova K. S., Rogozin I. B., Pavlov Y. I., and Koonin E. V. (2009) Evolution of DNA polymerases: an inactivated polymerase-exonuclease module in Pol epsilon and a chimeric origin of eukaryotic polymerases from two classes of archaeal ancestors. Biol. Direct 4, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dua R., Levy D. L., and Campbell J. L. (1999) Analysis of the essential functions of the C-terminal protein/protein interaction domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae pol epsilon and its unexpected ability to support growth in the absence of the DNA polymerase domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22283–22288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Asturias F. J., Cheung I. K., Sabouri N., Chilkova O., Wepplo D., and Johansson E. (2006) Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baranovskiy A. G., Lada A. G., Siebler H. M., Zhang Y., Pavlov Y. I., and Tahirov T. H. (2012) DNA polymerase delta and zeta switch by sharing accessory subunits of DNA polymerase delta. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 17281–17287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dua R., Levy D. L., Li C. M., Snow P. M., and Campbell J. L. (2002) In vivo reconstitution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon in insect cells: purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 7889–7896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dua R., Levy D. L., and Campbell J. L. (1998) Role of the putative zinc finger domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon in DNA replication and the S/M checkpoint pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30046–30055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jaszczur M., Flis K., Rudzka J., Kraszewska J., Budd M. E., Polaczek P., Campbell J. L., Jonczyk P., and Fijalkowska I. J. (2008) Dpb2p, a noncatalytic subunit of DNA polymerase epsilon, contributes to the fidelity of DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178, 633–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kraszewska J., Garbacz M., Jonczyk P., Fijalkowska I. J., and Jaszczur M. (2012) Defect of Dpb2p, a noncatalytic subunit of DNA polymerase varepsilon, promotes error prone replication of undamaged chromosomal DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 737, 34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y., Pursell Z. F., and Linn S. (2000) Identification and cloning of two histone fold motif-containing subunits of HeLa DNA polymerase epsilon. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsubota T., Tajima R., Ode K., Kubota H., Fukuhara N., Kawabata T., Maki S., and Maki H. (2006) Double-stranded DNA binding, an unusual property of DNA polymerase epsilon, promotes epigenetic silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32898–32908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bermudez V. P., Farina A., Raghavan V., Tappin I., and Hurwitz J. (2011) Studies on human DNA polymerase epsilon and GINS complex and their role in DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 28963–28977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aksenova A., Volkov K., Maceluch J., Pursell Z. F., Rogozin I. B., Kunkel T. A., Pavlov Y. I., and Johansson E. (2010) Mismatch repair-independent increase in spontaneous mutagenesis in yeast lacking non-essential subunits of DNA polymerase epsilon. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baranovskiy A. G., Babayeva N. D., Liston V. G., Rogozin I. B., Koonin E. V., Pavlov Y. I., Vassylyev D. G., and Tahirov T. H. (2008) X-ray structure of the complex of regulatory subunits of human DNA polymerase delta. Cell Cycle 7, 3026–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sanchez Garcia J., Baranovskiy A. G., Knatko E. V., Gray F. C., Tahirov T. H., and MacNeill S. A. (2009) Functional mapping of the fission yeast DNA polymerase delta B-subunit Cdc1 by site-directed and random pentapeptide insertion mutagenesis. BMC Mol. Biol. 10, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Suwa Y., Gu J., Baranovskiy A. G., Babayeva N. D., Pavlov Y. I., and Tahirov T. H. (2015) Crystal structure of the human Pol alpha B subunit in complex with the C-terminal domain of the catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 14328–14337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klinge S., Núñez-Ramírez R., Llorca O., and Pellegrini L. (2009) 3D architecture of DNA Pol alpha reveals the functional core of multi-subunit replicative polymerases. EMBO J. 28, 1978–1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baranovskiy A. G., Babayeva N. D., Zhang Y., Gu J., Suwa Y., Pavlov Y. I., and Tahirov T. H. (2016) Mechanism of concerted RNA-DNA primer synthesis by the human primosome. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 10006–10020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nuutinen T., Tossavainen H., Fredriksson K., Pirilä P., Permi P., Pospiech H., and Syvaoja J. E. (2008) The solution structure of the amino-terminal domain of human DNA polymerase epsilon subunit B is homologous to C-domains of AAA+ proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5102–5110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jaszczur M., Rudzka J., Kraszewska J., Flis K., Polaczek P., Campbell J. L., Fijalkowska I. J., and Jonczyk P. (2009) Defective interaction between Pol2p and Dpb2p, subunits of DNA polymerase epsilon, contributes to a mutator phenotype in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 669, 27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Netz D. J., Stith C. M., Stümpfig M., Köpf G., Vogel D., Genau H. M., Stodola J. L., Lill R., Burgers P. M., and Pierik A. J. (2011) Eukaryotic DNA polymerases require an iron–sulfur cluster for the formation of active complexes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kilkenny M. L., Longo M. A., Perera R. L., and Pellegrini L. (2013) Structures of human primase reveal design of nucleotide elongation site and mode of Pol alpha tethering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15961–15966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baranovskiy A. G., Zhang Y., Suwa Y., Babayeva N. D., Gu J., Pavlov Y. I., and Tahirov T. H. (2015) Crystal structure of the human primase. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 5635–5646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hogg M., Osterman P., Bylund G. O., Ganai R. A., Lundström E. B., Sauer-Eriksson A. E., and Johansson E. (2014) Structural basis for processive DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase varepsilon. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jain R., Vanamee E. S., Dzikovski B. G., Buku A., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash S., and Aggarwal A. K. (2014) An iron–sulfur cluster in the polymerase domain of yeast DNA polymerase epsilon. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 301–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang Y., Baranovskiy A. G., Tahirov T. H., and Pavlov Y. I. (2014) The C-terminal domain of the DNA polymerase catalytic subunit regulates the primase and polymerase activities of the human DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 22021–22034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zahurancik W. J., Baranovskiy A. G., Tahirov T. H., and Suo Z. (2015) Comparison of the kinetic parameters of the truncated catalytic subunit and holoenzyme of human DNA polymerase varepsilon. DNA Repair (Amst.) 29, 16–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garbacz M., Araki H., Flis K., Bebenek A., Zawada A. E., Jonczyk P., Makiela-Dzbenska K., and Fijalkowska I. J. (2015) Fidelity consequences of the impaired interaction between DNA polymerase epsilon and the GINS complex. DNA Repair (Amst.) 29, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Isoz I., Persson U., Volkov K., and Johansson E. (2012) The C-terminus of Dpb2 is required for interaction with Pol2 and for cell viability. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 11545–11553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun J., Shi Y., Georgescu R. E., Yuan Z., Chait B. T., Li H., and O'Donnell M. E. (2015) The architecture of a eukaryotic replisome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 976–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Georgescu R., Yuan Z., Bai L., de Luna Almeida Santos R., Sun J., Zhang D., Yurieva O., Li H., and O'Donnell M. E. (2017) Structure of eukaryotic CMG helicase at a replication fork and implications to replisome architecture and origin initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E697–E706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Otwinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., et al. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., and Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vassylyev D. G., Vassylyeva M. N., Perederina A., Tahirov T. H., and Artsimovitch I. (2007) Structural basis for transcription elongation by bacterial RNA polymerase. Nature 448, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kelley L. A., and Sternberg M. J. (2009) Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]