ABSTRACT

Expansions of polyglutamine (polyQ) tracts in different proteins cause 9 neurodegenerative conditions, such as Huntington disease and various ataxias. However, many normal mammalian proteins contain shorter polyQ tracts. As these are frequently conserved in multiple species, it is likely that some of these polyQ tracts have important but unknown biological functions. Here we review our recent study showing that the polyQ domain of the deubiquitinase ATXN3/ataxin-3 enables its interaction with BECN1/beclin 1, a key macroautophagy/autophagy initiator. ATXN3 regulates autophagy by deubiquitinating BECN1 and protecting it from proteasomal degradation. Interestingly, expanded polyQ tracts in other polyglutamine disease proteins compete with the shorter ATXN3 polyQ stretch and interfere with the ATXN3-BECN1 interaction. This competition results in decreased BECN1 levels and impaired starvation-induced autophagy, which phenocopies the loss of autophagic function mediated by ATXN3. Our findings describe a new autophagy-protective mechanism that may be altered in multiple neurodegenerative diseases.

KEYWORDS: ataxin-3, autophagy, Beclin 1, Huntington's disease, polyglutamine, spinocerebellar ataxia

Expansions of polyglutamine (polyQ) tracts in different proteins cause 9 neurodegenerative conditions, such as Huntington disease and various ataxias. Importantly, the wild-type counterparts of these disease proteins have shorter polyglutamine tracts that are conserved in many species, suggesting that they have biological functions. The presence of the same expansion mutation in different proteins suggests a common pathogenic mechanism. One process shared across these diseases is the propensity of the mutant proteins to aggregate. While this process has been implicated in pathogenesis, soluble forms of these proteins have also been shown to be toxic. However, toxic molecular mechanisms of such soluble expanded polyQ-containing species have been elusive.

When these mutant proteins reside in the cytoplasm, they have a high dependence on autophagy for their clearance. This is likely because the aggregated-oligomeric species are inaccessible to the proteasome and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Induction of autophagy enhances clearance of polyQ-expanded mutant proteins, like mutant HTT (huntingtin) and ATXN3, thereby attenuating their toxicity in cell and mouse models of Huntington disease and spinocerebellar ataxia, respectively.

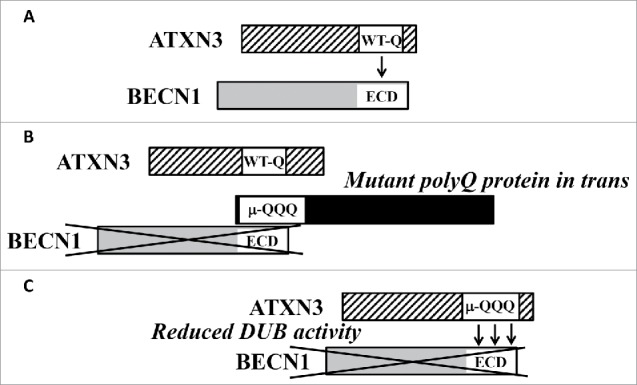

Our recent study revealed that wild-type ATXN3 is a deubiquitinase for BECN1. Importantly, we showed that the polyQ domain in wild-type ATXN3 is a key mediator of its interaction with the evolutionarily conserved domain of BECN1 (Fig. 1A). This interaction enables ATXN3 deubiquitination of BECN1, which protects it from degradation by the proteasome. BECN1 is a critical component of the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex that generates phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P) at autophagy initiation membranes and recruits autophagy proteins that are involved in autophagosome nucleation (i.e., the WIPI2-ATG16L1 complex). Thus, depletion of ATXN3 causes more rapid BECN1 degradation, resulting in decreased PtdIns3P formation and decreased autophagosome biogenesis.

Figure 1.

A proposed model describing ATXN3 activity in autophagy and its downregulation by mutant polyQ disease proteins. (A) The polyQ domain in wild-type ATXN3 (WT-Q) interacts with the evolutionarily conserved domain (ECD) of BECN1. This interaction allows the deubiquitinase activity of ATXN3 to protect BECN1 from degradation by the proteasome and thus enables autophagy. (B) Some expanded polyQ proteins (µ-QQQ) can compete in trans with the shorter polyQ stretch in wild-type ATXN3 for BECN1 binding. This competition destabilizes BECN1. (C) Expansion of the polyQ domain in ATXN3 decreases the deubiquitinase (DUB) activity toward BECN1 and enhances the interaction of mutant ATXN3 with BECN1. This would outcompete wild-type ATXN3 binding to BECN1 and destabilizes BECN1.

The finding that BECN1 contains polyQ binding pockets led us to test whether it could bind to proteins with polyQ expansions, and if such proteins would compete with the shorter polyQ stretch in ATXN3 for BECN1 binding (Fig. 1B). Our data suggest that isolated polyQ tracts are able to bind BECN1, whereas the longer expansions, which cause polyQ diseases, bind BECN1 to a greater extent than the shorter forms. Indeed, overexpression of disease proteins with polyQs (other than ATXN3) increases BECN1 ubiquitination and its degradation. This BECN1 degradation leads to impaired starvation-induced autophagy, a phenotype characteristic of BECN1 depletion. For example, we provided evidence, at least by overexpression studies, that the HTT exon 1 has these deleterious effects on autophagy. N-terminal fragments of HTT containing expanded polyQ domains are found in brains of Huntington disease patients and cause toxicity in cells and in Huntington disease mouse models. Furthermore, full-length mutant HTT binds BECN1 and competes for BECN1 binding with ATXN3, and fibroblasts from Huntington disease patients have impaired starvation-induced autophagy. Importantly, our data suggest that these competition effects can be mediated by soluble forms of proteins with polyQ stretches, thereby revealing a possible toxic function of nonaggregated mutant proteins with polyQ expansions.

The effects described above relate to mutant polyQ proteins competing with ATXN3 in trans, and these may be relevant to diverse polyglutamine diseases. However, because spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, also known as Machado-Joseph disease, is caused by a polyQ expansion in the ATXN3 protein itself, we studied its effects. We found that expansion of the polyQ tract in ATXN3 decreased its deubiquitinase activity toward BECN1 in an in vitro deubiquitination assay. However, the expanded disease-causing polyQ tract makes ATXN3 interact much more strongly with BECN1 (Fig. 1C). Thus, mutant ATXN3 would outcompete the wild-type-protein in this autosomal dominant disease, but the mutant protein would have decreased deubiquitinating activity, resulting in decreased BECN1 levels and impaired starvation-induced autophagy. Indeed, previous studies have shown that autophagosome formation is compromised in fibroblasts from patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 and that phenotypes in rodent models of this disease can be ameliorated by BECN1 overexpression.

The phenomena we have described are likely to be one of many mechanisms contributing to toxicity by mutant polyQ proteins. Indeed, there may be features of these proteins that affect autophagy via distinct mechanisms, as has been reported for mutant HTT. Furthermore, our proposed mechanisms will probably be nuanced due to the vast heterogeneity of the genetic landscapes associated with these diseases. First, the length of the polyQ tract in wild-type ATXN3 is polymorphic in humans, and it would be interesting to understand the extent to which this affects binding and activity. Furthermore, the disease alleles in all these conditions are also polymorphic in polyQ length, with longer expansions causing earlier disease onset. Further work will be required to test if shorter polyQ disease alleles have similar effects to longer disease alleles. An additional variable that is likely to have an impact on disease is the relative expression levels of ATXN3, the polyQ disease protein (e.g., mutant HTT) and BECN1 in different neuronal populations. This may contribute to the differential vulnerabilities of different brain regions in these diseases. Finally, it would be interesting to test if polyQ-containing cleavage products of some of the disease proteins are more toxic in this paradigm, compared with their uncleaved full-length counterparts.

These data raise the question of whether and to what extent polymorphisms in the wild-type and expanded polyQ stretches may contribute to the variabilities in clinical onset, presentation and progression of these devastating diseases.

Abbreviations

- DUB

deubiquitinase

- ECD

evolutionarily conserved domain

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- PtdIns3P

phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate

Disclosure of potential conflicts of Interest

F.M.M. is currently an employee of Eli Lilly & Co. Ltd.

Funding

We are grateful to Wellcome Trust (Principal Research Fellowship to DCR.) (095317/Z/11/Z), Wellcome Trust Strategic Grant to Cambridge Institute for Medical Research (100140/Z/12/Z)), National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Center at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Addenbrooke's Charitable Trust and Federation of European Biochemical Societies (FEBS Long-Term Fellowship to A.A.) for funding.