ABSTRACT

Nigeria has made remarkable progress against polio, but 2 wild polio virus cases were reported in August 2016; putting an end to 2 y without reported cases. We examined the extent of geographical disparities in childhren not vaccinated against polio and examined individual- and community-level predictors of non-vaccination in Nigeria. We applied multilevel logistic regression models to the recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. The percentage of children not routinely vaccinated against polio in Nigeria varied greatly and clustered geographically, mainly in north-eastern states, with a great risk of spread of transmission within these states and potential exportation to neighboring states and countries. Only about one-third had received all recommended 4 routine oral polio vaccine doses. Non-vaccinated children tended to have a mother who had no formal education and who was currently not working, live in poorer households and were from neighborhoods with higher maternal illiteracy rates.

Introduction

As recently as 2012, Nigeria accounted for more than half of all polio cases worldwide.1 However, due to concerted efforts by all levels of government, civil society, religious leaders, polio partners and thousands of dedicated health workers and community volunteers, Nigeria successfully stopped wild poliovirus transmission for 2 y. Between July 2014 and July 2016, Nigeria brought the world one major step closer to ending a disease that has paralysed millions of people worldwide. This monumental achievement was, however, short-lived because in August 2016 2 cases of wild polio virus were detected in children in Borno State in the north eastern part of the country.2,3 It is critical that we seize this opportunity to intensify immunisation and surveillance efforts to end polio for good and ensure that future generations of children are free from this devastating disease.1 This requires continued vigilance to protect the gains and ensure that the current transmission in Borno is interrupted and does not spread to other parts of Nigeria and neigbouring countries. Immunisation activities must continue to interrupt the transmission in Borno and surveillance must be strengthened to be able to rapidly detect potential re-introduction or re-emergence of the virus in any parts of the country. Since the poliovirus can lurk in sewage and elsewhere, and since there can be up to 200 asymptomatic cases of the disease for every paralytic one,4 there is no telling how many human virus reservoirs are still at large in Nigeria.

Minimising the risk of polio can be assisted by recognizing the geographical distribution of non-vaccinated children and identifying areas of high risk for non-vaccination. Policy makers and researchers often want to know the distribution of a disease incidence by geographical region or associated environmental factors.5 The need to map spatial variation in polio risk in Nigeria is more important now than ever.6 Such a focus is consistent with the National Routine Immunization Strategic Plan, NRISP (2013–2015)7 was set-up to improve delivery of routine immunization services in a collective, organized manner to reduce the number of unimmunised children in all localities; and to mobilizing the resources needed to provide high-quality immunization services using the Reaching Every Ward (REW) strategy. The vision of the Nigeria National Primary Health Care Development Agency is to achieve and sustain interruption of polio virus transmission, with special focus on the most vulnerable, high risk and insecure populations. In 2017, the National Polio Eradication Emergency Plan (NPEEP)8 outlines key strategic priorities to ensure that interruption of poliovirus transmission is achieved and sustained, by: (1) sustaining resilience; 2 increasing access to vaccination in security challenged areas and internally displaced populations; 3 enhancing Supplemental Immunisation Activities quality in prioritized vulnerable areas; 4 ensuring robust outbreak response across all states; 5 enhancing routine immunization; 6 intensifying surveillance; 7 strengthening cross border collaboration; and8 polio transition planning. A geographical risk analysis would also help to identify states and communities that have relatively high proportions of children who have received no polio vaccines, indicative of polio immunity gaps, which may in turn lead to the development and implementation of more effective geographically differentiated intervention programmes. In this regard, mapping and investigating risk variations in children not vaccinated against polio is an invaluable tool. Furthermore, mapping the variation in risk can help improve the targeting of scarce resources for public health interventions. This information would be useful for both micro-targeting future programmes and identifying locales where progress has been made to investigate interventional, socio-economic, and cultural conditions that may have contributed to the apparent progress.

As Nigeria continues to grapple with a range of program and policy challenges related to childhood immunisation, we believe that one important element in changing the status quo is a comprehensive and relevant evidence base that would equip states in the country to take informed actions. Without comprehensive information about the current patterns of non-vaccinated and undervaccinated children, and factors associated with failure to complete the full series of recommended vaccines, it is hard to plan substantial public health programmes that would improve the childhood immunisation program in the country. Much research in Nigeria has focused on individual compositional factors associated with childhood immunisation coverage9-11 Indeed, we found no published studies that had examined contextual factors associated with childhood polio non-vaccination. This neglect is important given the central role of neighborhoods in forming parental habits,12-17 as they shape individual opportunities and expose residents to multiple risks and resources over the life course.18,19 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine individual- and contextual factors associated with childhood polio non-vaccination in Nigeria. In addition, we used exploratory spatial analysis to identify Nigerian states with unusually high percentages of polio non-vaccinated children.

Results

Sample characteristics

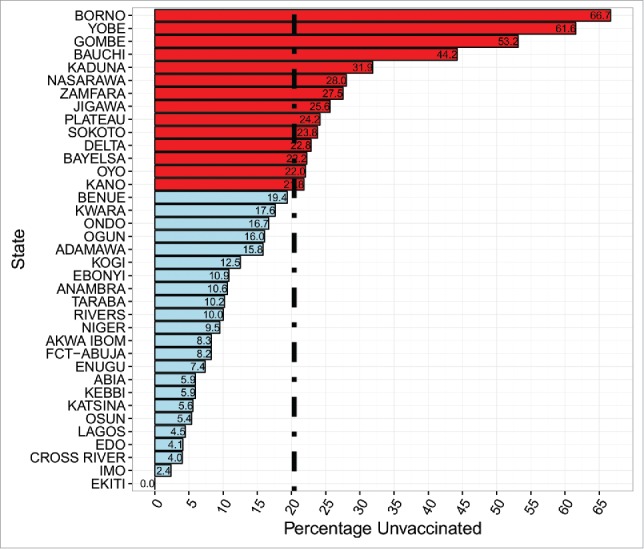

The summary characteristics of the included sample is shown in Table 1. Among 5,734 children aged 12 to 23 months included in this study, 52% were male. Most of the children were residing in rural areas. Half of the mothers were aged 25 to 34 years, and 48% of them had no formal education. Most (71%) of the mothers were currently working, and about one-third of them had no access to media (television, radio or newspaper). Only about one-third of children were vaccinated with all the 4 recommended doses of oral polio vaccine (i.e. at birth, 6 weeks, 10 weeks and 14 weeks), almost half were undervaccinated against polio and one in 5 have received none of the 4 doses. However, the percentage of non-vaccinated children varied greatly across the 37 states, ranging from zero percent in Ekiti to 67% in Borno State (Fig. 1). The proportion of non-vaccinated children were similar for either sexes (male vs female). Non-vaccinated children were more likely to come from poorer households compared with children from the richer households.

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of the Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey, 2013.

| Non-vaccinated |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unweighted sample size | Weighted Percentage(95% CI) | No | Yes | p-value | |

| Polio vaccination | ||||||

| Non-vaccinated | 1,173 | 21.3 (19.5 to 23.2) | ||||

| Under vaccinated | 2,785 | 48.6 (46.7 to 50.6) | ||||

| Fully vaccinated | 1,796 | 30.1 (28.3 to 32.0) | ||||

| Individual-level | ||||||

| Sex | 0.327 | |||||

| Female | 2,744 | 48.0 (46.5 to 49.5) | 78.1 | 21.9 | ||

| Male | 3.010 | 52.0 (50.5 to 53.5) | 79.3 | 20.7 | ||

| Age (in years) | 0.0002 | |||||

| 15–24 | 1,613 | 28.8 (27.4 to 30.3) | 74.4 | 25.6 | ||

| 25–34 | 2,842 | 48.9 (47.3 to 50.5) | 81.1 | 18.9 | ||

| 35–49 | 1,299 | 22.3 (20.9 to 23.7) | 79.1 | 21.9 | ||

| Wealth index | 0.0001 | |||||

| Poorer | 1,866 | 33.6 (30.9 to 36.3) | 66.8 | 33.2 | ||

| Middle | 1,885 | 31.3 (29.0 to 33.4) | 77.7 | 22.3 | ||

| Richer | 2,003 | 35.1 (32.8 to 37.5) | 91.1 | 08.9 | ||

| Education | 0.0001 | |||||

| No education | 2,607 | 47.6 (45.0 to 50.2) | 67.6 | 32.4 | ||

| Primary | 1,116 | 18.0 (16.7 to 19.4) | 82.7 | 17.3 | ||

| Secondary+ | 2,301 | 34.4 (32.3 to 36.7) | 92.0 | 08.0 | ||

| Employment status | 0.0001 | |||||

| Current working | 3,816 | 71.1 (69.2 to 72.8) | 82.6 | 17.4 | ||

| Not working | 1,938 | 28.9 (27.2 to 30.7) | 69.3 | 30.7 | ||

| No media access | 0.0001 | |||||

| No | 4,106 | 67.2 (65.2 to 69.2) | 84.4 | 15.6 | ||

| Yes | 1,648 | 32.8 (30.8 to 34.8) | 67.2 | 32.8 | ||

| Neighborhood-level | ||||||

| Place of residence | 0.0001 | |||||

| Urban | 1,922 | 35.9 (33.5 to 38.2) | 85.9 | 14.1 | ||

| Rural | 3,832 | 64.1 (61.7 to 66.5) | 74.7 | 25.3 | ||

| Geopolitical region | 0.0001 | |||||

| North Central | 862 | 13.9 (12.4 to 15.6) | 82.2 | 17.8 | ||

| North East | 1,169 | 17.3 (15.7 to 19.1) | 53.7 | 46.3 | ||

| North West | 1,753 | 35.5 (33.2 to 37.8) | 79.1 | 20.9 | ||

| South East | 550 | 09.3 (07.9 to 10.9) | 92.2 | 07.8 | ||

| South South | 722 | 10.0 (08.9 to 11.3) | 89.7 | 10.3 | ||

| South West | 698 | 13.9 (12.3 to 15.6) | 88.8 | 11.2 | ||

| Poverty rate | 0.0001 | |||||

| Low | 2,965 | 50.6 (47.2 to 54.0) | 87.4 | 12.6 | ||

| High | 2,798 | 49.4 (46.0 to 52.7) | 69.8 | 30.2 | ||

| Unemployment rate | 0.0001 | |||||

| Low | 2,946 | 51.0 (47.0 to 55.0) | 85.6 | 14.4 | ||

| High | 2,808 | 49.0 (45.0 to 53.0) | 71.6 | 28.4 | ||

| Illiteracy rate | 0.0001 | |||||

| Low | 2,951 | 51.2 (48.1 to 54.3) | 88.7 | 11.3 | ||

| High | 2,803 | 48.8 (45.7 to 51.8) | 78.7 | 21.3 | ||

Figure 1.

Percentage of non-vaccinated (for polio) children by State, Nigeria 2013.

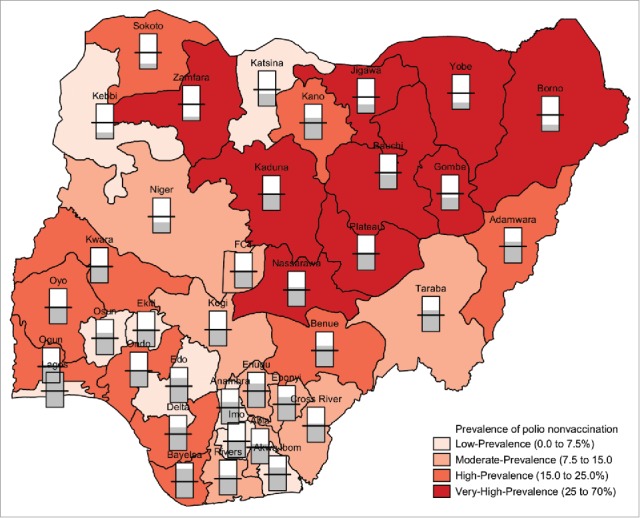

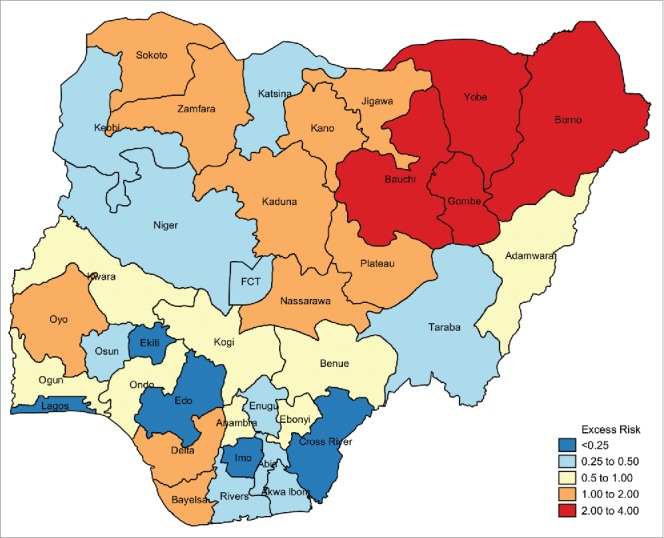

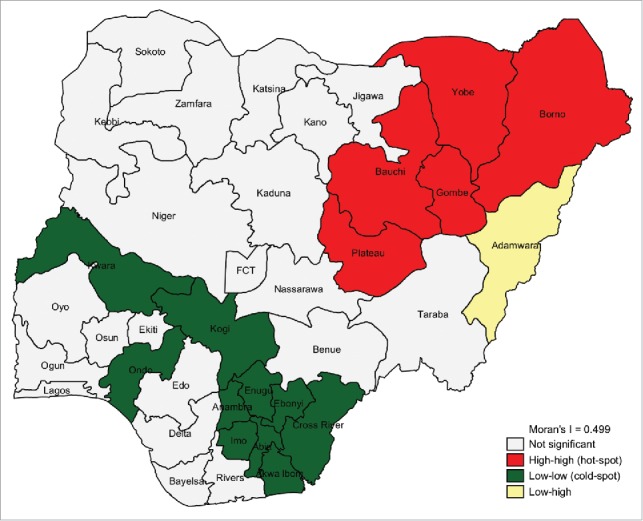

Spatial distribution and autocorrelation

The spatially smoothened percentile map is shown in Fig. 2. Nine states had the percentage of polio nonvaccinated children between 0% and 7.5%; 10 states had a medium prevalence of polio non-vaccination, between 7.5% and 15%; 9 states had a high prevalence of polio non-vaccination, between 15% and 25%; and 9 states had a very high prevalence of polio non-vaccination i.e., 25% to 70%. As shown in Fig. 2, there is a strong positive correlation between percentage of non-vaccinated childhood and maternal illiteracy rate. The ‘excess' hazard map depicted in Fig. 3 shows distribution of the excess risk, which was a ratio of the observed number over the expected number of non-vaccinated children. Five states marked in blue had lower rates than expected, as shown by risk values less than 0.5. In contrast, 4 states in red had rates higher than expected, with risk values greater than 2. Figure 4 shows results of global spatial autocorrelation analyses for polio non-vaccinated children. The results of Local Moran's I show statistically significant spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I = 0.499, p = 0.001). Fives states in North East Nigeria belong to High-high (hot-spot) clusters. These are states with high percentages of polio non-vaccinated children compared with similar neighboring states. The states marked in green belong to Low-low (cold-spot) clusters, mainly from the southern part of Nigeria. These are states with low percentages of polio non-vaccinated children compared with similar neighboring states. Adamawa state is the only Low-high cluster state in North Est Nigeria, potentially an outlier. In other words, Adamawa is a state with a low percentage of polio non-vaccinated children and a high percentage of neighboring states with substantial proportions of non-vaccinated children. The other states marked in white are locations with no statistically significant autocorrelation.

Figure 2.

Bivariate map of spatially smoothed percentile map of percentage of non-vaccinated (for polio) children and maternal illiteracy rates by State, Nigeria 2013.

Figure 3.

Excess risk map of non-vaccinated (for polio) children by State, Nigeria 2013.

Figure 4.

Spatial autocorrelation cluster map for non-vaccinated (for polio) children by State, Nigeria 2013.

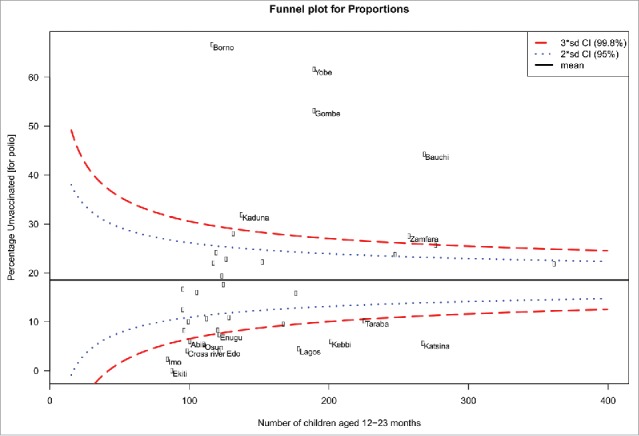

Special- and common-cause variations

As shown in Fig. 5, there is a wide variation in the non-vaccination rate between the 37 states. The funnel plot identifies 20 (54%) states within the 99% control limits indicating common-cause variation. Six (16%) states were above the upper control limit (higher than the average) and 11 (30%) states were below the lower control limit (lower than the average), indicating special-cause variation.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot showing common- and special-cause variations in childhood unvaccination for polio in Nigeria.

Factors associated with non-vaccination against polio

The results of different models are shown in Table 2. In the fully adjusted model controlling for the effects of individual- and neighborhood-level factors, we found that household wealth index, maternal educational attainment, maternal employment status, geopolitical region and neighborhood illiteracy rate were significantly associated with children being non-vaccinated against polio. Children from the poorer households were 88% more likely to be non-vaccinated compared with children from the richer households (OR = 1.88, 95% CrI 1.29 to 2.74). Children of mothers with no formal education were 178% more likely to be non-vaccinated compared with children of mothers with secondary or higher education (OR = 2.78, 95% CrI 2.07 to 3.70). Children of mothers not currently working were 46% more likely to be non-vaccinated compared with children of mothers currently working (OR = 1.46, 95% CrI 1.21 to 1.76). Compared with children from South East Nigeria, children from North East Nigeria were 4 timestimes more likely to be non-vaccinated for polio (OR = 4.27, 95% CrI 1.23 to 12.04). Children living in neighborhoods with high illiteracy rates were almost twice as likely to be non-vaccinated (OR = 2.46, 95% CrI 1.91 to 3.33).

Table 2.

Individual compositional and contextual factors associated with polio unvaccination, Nigerian Demographic and Health Surveys data, 2013.

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | Model 4d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | OR (95% CrI) | |

| Fixed-effect | ||||

| Individual-level factors | ||||

| Male (vs female) | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.13) | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.13) | ||

| Age (completed years) | ||||

| 18–24 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| 25–34 | 1.11 (0.88 to 1.37) | 1.09 (0.86 to 1.36) | ||

| 35+ | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.19) | 0.99 (0.80 to 1.21) | ||

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorer | 2.19 (1.56 to 3.01) | 1.88 (1.29 to 2.74) | ||

| Middle | 1.85 (1.42 to 2.38) | 1.69 (1.27 to 2.21) | ||

| Richer | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Education | ||||

| No education | 3.26 (2.32 to 4.40) | 2.78 (2.07 to 3.70) | ||

| Primary | 1.99 (1.46 to 2.60) | 1.94 (1.47 to 2.52) | ||

| Secondary or higher | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Current not working | 1.50 (1.24 to 1.81) | 1.46 (1.21 to 1.76) | ||

| No media access | 1.19 (0.99 to 1.43) | 1.16 (0.96 to 1.39) | ||

| Neighborhood-level factors | ||||

| Geopolitical region | ||||

| North Central | 2.40 (0.55 to 5.83) | 2.64 (0.73 to 7.81) | ||

| North East | 4.36 (0.90 to 12.21) | 4.27 (1.23 to 12.04) | ||

| North West | 1.12 (0.37 to 3.98) | 1.10 (0.32 to 2.93) | ||

| South East | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| South South | 2.29 (0.62 to 6.13) | 2.60 (0.92 to 6.49) | ||

| South West | 1.95 (0.42 to 5.56) | 2.33 (0.53 to 7.79) | ||

| Rural (vs urban) | 1.44 (1.03 to 1.90) | 1.12 (0.80 to 1.54) | ||

| High (vs low) poverty rate | 1.61 (1.13 to 2.20) | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.62) | ||

| High (vs low) unemployment rate | 1.46 (1.10 to 1.90) | 1.27 (0.97 to 1.64) | ||

| High (vs low) illiteracy rate | 3.36 (2.29 to 4.81) | 1.92 (1.29 to 2.75) | ||

| Random effects | ||||

| State-level | ||||

| Variance (95 CrI) | 1.66 (0.94 to 2.85) | 0.98 (0.55 to 1.71) | 0.95 (0.50 to 1.69) | 0.89 (0.46 to 1.59) |

| VPC (%) | 26.2 (17.8 to 36.0) | 18.7 (12.0 to 27.3) | 17.9 (10.8 to 26.4) | 17.3 (10.3 to 25.8) |

| MOR (%, 95% CrI) | 3.42 (2.52 to 5.00) | 2.57 (2.03 to 3.48) | 2.54 (1.96 to 3.46) | 2.46 (1.91 to 3.33) |

| Explained variation (%) | reference | 41.0 (40.0 to 41.9) | 42.5 (40.6 to 47.2) | 46.4 (44.2 to 51.3) |

| Neighborhood-level | ||||

| Variance (95 CrI) | 1.38 (1.07 to 1.78) | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.27) | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.42) | 0.98 (0.70 to 1.28) |

| VPC (%, 95% CrI) | 48.0 (37.9 to 58.5) | 37.1 (27.7 to 47.5) | 38.1 (28.4 to 48.6) | 36.2 (26.0 to 46.6) |

| MOR (%, 95% CrI) | 3.07 (2.68 to 3.57) | 2.55 (2.24 to 2.93) | 2.69 (2.36 to 3.11) | 2.57 (2.22 to 2.95) |

| Explained variation (%) | reference | 30.5 (28.9 to 33.0) | 22.2 (20.6 to 24.3) | 29.4 (28.0 to 34.9) |

| Model fit statistics | ||||

| DIC | 4600 | 4513 | 4564 | 4502 |

| Sample size | ||||

| State-level | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 |

| Neighborhood-level | 890 | 890 | 890 | 890 |

| Individual-level | 5,754 | 5,754 | 5,754 | 5,754 |

Model 1 – empty null model, baseline model without any explanatory variables (unconditional model)

Model 2 – adjusted for only individual-level factors

Model 3 – adjusted for only neighborhood-level factors

Model 4 – adjusted for individual-, and neighborhood-level factors (full model)

OR – odds ratio, CrI – credible interval, MOR – median odds ratio, VPC – variance partition coefficient, DIC – Bayesian Deviance Information Criteria

Neighborhood effect and clustering

As shown in Table 2, in Model 1 (unconditional model), there was a significant variation in odds of non-vaccination against polio across the states ( 1.66, 95% CrI 0.94 to 2.85) and across the neighborhoods ( 1.38, 95% CrI 1.07 to 1.78). According to the intra-state and intra-neighborhood correlation coefficient, 26.2% and 48.0% of the variance in odds of being non-vaccinated against polio could be attributed to the state- and neighborhood-level factors, respectively. Results from the median odds ratio (MOR) also confirmed evidence of neighborhood and state contextual phenomena shaping childhood non-vaccination against polio.

From the full model (Model 4), it was estimated that if a child moved to another neighborhood or another state with a higher probability of childhood non-vaccination, the median increase in their odds of being non-vaccinated would be 2.46 (95% CrI 1.96 to 3.33) and 2.57-fold (95% CrI 2.22 to 2.95) respectively. As judged by the proportion change in variance between the full and empty models, more than half and almost one third of the variance in the odds of non-vaccination across the states and neighborhoods respectively were explained by individual- and neighborhood factors.

Discussion

Main findings

Drawing upon multilevel and spatial analyses perspectives, in this paper we have offered an alternative to more traditional ways of thinking about the variations and factors associated with childhood polio vaccination coverage in Nigeria. In particular, we have demonstrated that individual and neighborhood contexts in which children live are associated with their immunisation status. We found that there is wide variation in the burden of polio non-vaccinated childhren in Nigeria, with almost half of the states showing evidence of special-cause variation which merits further investigation to identify possible causes. More importantly, the findings uncover new evidence about geographical clustering in children who have not received any of the 4 routine doses of oral polio vaccines. About 26% and 48% of the variation in non-vaccinated childhren is conditioned by differences between neighborhoods and states, respectively. For example, if a child moves from areas with a low percentage of non-vaccinated children to another neighborhood or another state with a higher probability of children being non-vaccinated, their odds of becoming non-vaccinated would increase by about 146% and 157%, respectively. It is instinctual that people from the same neighborhood may be more similar to each other in relation to their attitudes and opportunities toward childhood immunisation than to others from different neighborhoods.20 On these grounds, we might conclude that there is some evidence for a possible neighborhood and state contextual phenomenon shaping a common childhood vaccination status. These findings underscore the need to implement public health prevention strategies not only at the high-risk children level, but also high-risk neighborhoods.

Comparison with other studies

As household wealth decreases, the percentage of non-vaccinated children increases. The influence of poverty on child immunisation has been well documented.21 Although polio and other childhood vaccines are administered free of charge to children in Nigeria, the inability of mothers to raise money for transport to the immunisation center could constitute an obstacle to vaccination uptake for children. This is a challenge that is likely to be faced by women living in the remote communities. The issue of lack of transport fare for poor women can be taken care of by organizing regular outreach vaccination sessions in under-served areas. Maternal education is an important correlate of immunisation uptake. The proportion of non-vaccinated children is higher among non-educated women compared with those who are educated. This finding has been reported in previous studies.22,23 Results further showed that women's employment status is associated with child non-vaccination.24 Children of non-working mothers are more likely to be non-vaccinated compared with children of working mothers. This may be attributed to the fact that working mothers have the financial means to reach the facility where the vaccines are administered. They may also be exposed to information on vaccination through interactions at their places of occupation. The neighborhood has been described to influence childhood immunisation.25 This was revealed in our study in that children living in the North East Region are more likely to be non-vaccinated compared with children in the South East Region of the country. More so, children living in neighborhoods with high rates of illiteracy are more likely to be non-vaccinated.

Policy implications

The study revealed that most children not vaccinated against polio in Nigeria live in the northern part of the country. This part is home to: all the 9 states with very high percentages (25% to 70%) of non-vaccinated children; the 4 states with observed number of non-vaccinated children greater than the expected number, and; all the 5 states regarded as the hot spots for non-vaccination against polio. These states also have numerous camps of internally displaced persons that have poor public health settings which mostly do not cater for the need of the children.26 It is importan to note that at the time of survey, “much of Borno was under the control of the terrorist group Boko Haram and vaccinators had been unable to reach hundreds of thousands of children thus disrupting the surveillance of the virus.”2 This puts this part of the country in the top priority for targeted interventions to make Nigeria a polio-free country. The success recorded in the southern part of the country may, in the long run, be overshadowed by the poor state of polio vaccinations in the north if appropriate interventions are not implemented. Polio transmission could become more widesepread in the north and transmission could be exported to the currently polio-free southern part.

We identified Borno, Yobe, Gombe and Bauchi as the states with high percentages of polio non-vaccinated children when compared with other states. There is a need to further explore the risk factors for non-vaccination that are peculiar to these areas. These states may require both universal and targeted approaches to tackling polio non-vaccination. This in effect will help prevent ‘prevention paradox' that is associated with a universal approach. One of these states, i.e., Borno State, has an ongoing outbreak of wild polio virus transmission. States such as Ekiti, Edo and Lagos appear to have the lowest percentages of polio non-vaccinated childhren in Nigeria. Inference that could be drawn from this finding is that there are ‘special practices' from these states that could be identified as good practice. This should also warrant further investigation to identify what these practices are.

The substantial progress in polio edradication efforts in Nigeria would have been impossible without the support and commitment of donors and development partners. Their continued support, along with continued domestic funding from Nigeria, will be essential to interrupt polio transmission in Nigeria and render Africa polio-free. As long as polio exists anywhere, it's a threat to children everywhere. The 2 recent cases of wild polio virus in Nigeria particularly highlight the need to prioritise immunisation of children in hard-to-reach areas such as the Lake Chad region, which includes North East Nigeria and spans several countries and is often affected by conflict and large population movements. Reaching these children requires vaccinating populations as they move in and out of inaccessible areas and using local groups and organisations, such as religious institutions and community based organisations, to negotiate access for vaccination teams. Nigeria has experience in implementing similar interventions, known as the “hit and run strategy,”3,27 which should be rolled out more extensively in the north-eastern states.

Limitations and strengths of this study

Our findings should be considered in light of the following potential limitations. We did not have longitudinal neighborhood measurements, which may generate selection bias; therefore, these relationships should be interpreted as associations only.13,28 In addition, demographic and health surveys do not collect data on household income or expenditure, the traditional indicators used to measure wealth. The assets-based wealth index used here is only a proxy indicator for household economic status, and it may not produce results identical to those obtained from direct measurements of income and expenditure.29,30 Another important limitation is that the study did not assess the delivery of oral polio vaccines during supplementary immunisation activities (SIAs), which are also crucial part of the polio endgame. Our study focused only on polio vaccination. We did not incorporate an assessment of the possible effect of interactions between knowledge of vaccines generally, and whether families that have received other vaccines are more likely to vaccinate their children against polio significantly more. Further research using structural equation modeling approach may be necessary to assess such interaction or moderating effects. Finally, there may be potential reporting bias due to education status of mothers. It is possible the childhood polio vaccination status was more accurately reported in households with higher economic status and superior literacy.

Despite these limitations, the study's strengths are significant. It is a large, population-based study with national coverage and high response rates. Demographic and health surveys have some important advantages when compared with other surveys. They are nationally representative, allowing for conclusions that cover the entire nation. The 2013 NHDS was designed to provide population and health indicator estimates at the national, zonal, and state levels. The sample design allowed for specific indicators to be calculated for each of the 6 zones, 36 states, and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. In addition, with the 3-stage sampling survey design, selection bias and increased sampling error and reduction in precision were minimised using stratification, multistaging and the systematic selection of households from each cluster. We explored the variation in childhood polio non-vaccination by using an innovative ‘within-data analysis triangulation method'. We used 3 analytical methods to analyze data from the survey - multilevel, funnel plots and spatial cluster analyses. This facilitated the validation and reliability of analyses through cross verification of methods used. In addition, there are advantages to studying factors associated with childhood non-vaccination using a multilevel approach; neighborhood level analyses identify social, cultural, and economic contexts in which an individual lives and experiences ‘healthy' behavioral outcomes. Understanding the relative contribution of individual, community and societal factors is important for policymakers to design and target public health interventions. Finally, the Bayesian approach we adopted has the additional advantage of being able to produce a far more robust estimate with better properties and yields unbiased estimates.31,32

In conclusion, the percentage of children who have not received routine oral polio vaccines varied greatly across Nigeria and clustered geographically, mainly in the northern part of the country, thereby increasing the risk of transmitting polio virus to both non-vaccinated and undervaccinated children. Furthermore, individual-level and community contextual characteristics were independently associated with childhood vaccination status, suggesting that interventions to reduce childhood polio non-vaccination should focus on high-risk groups of people as well high risk places.

Methods

Study setting

Nigeria covers a total area of about 923,768 km2s. It is the 32nd largest country in the world in terms of land mass and the most populous country in Africa with a recent estimate of its population as 140,431,790.33 About 68% of the Nigerian population lives in rural areas. There are 374 identifiable ethnic groups in Nigeria with varying languages, customs and cultures.33 The largest ethnic groups are the Yoruba, Hausa/Fulani and Igbo which collectively account for about 68% of the population.33

Nigeria is divided into 37 states and further divided into 774 local government areas (LGAs) all within 6 geopolitical zones (South West, South South, South East, North West, North Central and North East). The sampling frame for this study was made up of a list of all enumeration areas (clusters)33 established by the General Population and Housing Census conducted in 2006 i.e., the census that preceded the survey on which this study is based.

Study design and sampling technique

This study was based on secondary analyses of cross-sectional population-based data from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey.33 The survey33 was conducted to collect data on demographic, environmental, socioeconomic, and health issues (family planning, infertility, immunisation, nutritional and health status of children, their mothers and the fathers). The sample for the 2013 NDHS was nationally representative and covered the entire population in the country. The most recent the list of enumeration areas (EAs) prepared for the 2006 Population Census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria was used as the sampling frame. The participants were selected using a stratified 3-stage cluster design consisting of 904 clusters, 372 in urban areas and 532 in rural areas (Box 1). A representative sample of 40,680 households was selected for the survey, with a minimum target of 943 completed interviews per state. In the first stage, 893 localities were selected with probability proportional to size and with independent selection in each sampling stratum. In the second stage, one EA was randomly selected from most of the selected localities with an equal probability selection. In the third stage of selection, a fixed number of 45 households were selected in every urban and rural cluster through equal probability systematic sampling based on the newly updated household listing. All women age 15–49 who were either permanent residents of the households in the 2013 NDHS sample or visitors present in the households on the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed. In a subsample of half of the households, all men age 15–49 who were either permanent residents of the households in the sample or visitors present in the households on the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed.

| Box 1. Nigeria NDHS 3-Stage Cluster Sampling | ||

| Stage |

Approach |

Outcome |

| 1st Stage Selection of localities | • Sampling frame:2006 National census Enumeration Areas (EA) • Stratification of states into urban /rural • Independent selection in each stratum with probability of selection proportional to size. | 893 localities nationally |

| 2nd Stage Selection of EAs/clusters | • Random selection of EAs (equal probability selection). • Mapping and household listing of selected clusters. • Household lists as Secondary sampling units (SSU). | 904 clusters based on EAs 372 (urban) and 532 (rural) |

| 3rd Stage Selection of households | 45 Households selected in each rural /urban cluster | 40,680 Households (Urban 16,740, Rural 23,940) |

Data collection

Data collection procedures have been published elsewhere.33 Data were collected by conducting face-to-face interviews with women and men who met the eligibility criteria. Among all eligible individuals and households, participation rates were 98% for household, 98% for women and 95% for men.33 Each woman was asked to provide a detailed history of all her live births in chronological order, including whether a birth was single or multiple, assigned sex of the child, date of birth, survival status, age of the child on the date of interview if alive and age at death of each live birth, if the child was not still alive.

Ethical consideration

This study is based on an analysis of existing survey data with all identifier information removed. The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the ICF Macro at Calverton in the USA and by the National Health Research Ethics Committee in the Federal Ministry of Health in Nigeria. All study participants gave informed consent before participation and all information was collected confidentially.

Outcome variable

We defined non-vaccinated child for polio as a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if a child aged 12 to 23 months has not received any of the 4 routine doses of oral polio vaccine (polio 0 at birth, polio 1 at 6 weeks, polio 2 at 10 weeks and polio 3 at 14 weeks) and 0, otherwise.

Determinant variables

Individual level factors

The following individual-level factors were included in the models: sex of the child (male versus female), mother's age in completed years (15 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44 or 45 or older), mothers's educational attainment (no education, primary, secondary or higher) and mother's employment status (currently working or not). Access to media such as radio, television or magazine (yes vs. no). NDHS did not collect direct information on household income and expenditure. We used NDHS wealth index as a proxy indicator for socioeconomic position. The methods used in calculating NDHS wealth index have been described elsewhere.30,34 Briefly, an index of economic status for each household was constructed using principal components analysis based on the following household variables: number of rooms per house, ownership of car, motorcycle, bicycle, fridge, television and telephone as well as any kind of heating device. From these criteria the NDHS wealth index tertiles (poor, middle and rich) were calculated and used in the subsequent modeling.

Neighborhood-level factors

We used the term neighborhood to describe clustering within the same geographical living environment. Neighborhoods were based on sharing a common primary sample unit within the NDHS data. The sampling frame for identifying primary sample unit in the NDHS is usually the most recent census. The unit of analysis was chosen for 2 reasons. First, primary sample unit is the most consistent measure of neighborhood across all the surveys,35 and thus the most appropriate identifier of neighborhood for this cross-region comparison. Second, for most of the NDHS conducted, the sample size per cluster meet the optimum size with a tolerable precision loss.36

The following neighborhood-level factors were included in the models: place of residence (rural or urban area), geopolitical region (North Central, North East, North West, South East, South South or South West) neighborhood poverty-, illiteracy- and unemployment rates. We categorised neighborhood poverty-, illiteracy- and unemployment rates into 2 categories (low and high), to allow for non-linear effects and provide results that were more readily interpretable in the policy arena. Median values served as the reference group for comparison.

Descriptive analyses

In the descriptive statistics the distribution of respondents by key variables were expressed as percentages. All cases in the NDHS data were given weights to adjust for differences in probability of selection and to adjust for non-response to produce the proper representation. Individual weights were used for descriptive statistics in this study, using Stata 14 for Windows.37

Multilevel modeling approaches

Given the hierarchical structure of the sample and the binaryoutcome, a logistic multilevel modeling approach was adopted.38 A 3-level model with a binary response (y, non-vaccinated for polio or not) for child i living in community j in state k of the form:

| (1) |

The probability was relatedto a set of categorical predictors, X; and a random effect foreach level, by a logit-link function as

| (2) |

The linear predictor on the right-hand side ofthe equation consisted of a fixed part () estimating the conditional coefficients for the explanatory, and 2 random intercepts attributable tocommunities () andstates () with each assumed to have an independent and identicaldistribution and variance estimated at each level.

We constructed 4 models. The first model, an empty or unconditional model without any explanatory variables, was specified to decompose the amount of variance that existed between state and neighborhood levels. The second model contained only individual-level factors, and the third model contained only neighborhood-level factors. Finally, the fourth model simultaneously controlled for individual-, and neighborhood-level factors (Full Model).

Fixed effects (measures of association)

The results of fixed effects (measures of association) were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% credible intervals (CrIs). Bayesian statistical inference provides probability distributions for measures of association (ORs), which can be summarized with 95% credible intervals (95% CrI), rather than 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Random effects (measures of variation)

The possible contextual effects were measured by the intraclass correlation (ICC) and median odds ratio (MOR). We measured similarity between respondents in the same neighborhood and within the same state using ICC. The ICC represents the percentage of the total variance in the probability of reporting childhood unvaccination for polio that is related to the neighborhood- and state-level, i.e., measure of clustering of odds of reporting childhood unvaccination for polio in the same neighborhood and state. The ICC was calculated by the linear threshold (latent variable method).38 Following the ideas of Larsen et al. on neighborhood effects,39 we reported the random effects in terms of odds. The MOR measures the second or third level (neighborhood or state) variance as odds ratio and estimates the probability of childhood unvaccination for polio that can be attributed to neighborhood and state context. MOR equal to one indicates no neighborhood or state variance. Conversely, the higher the MOR, the more important are the contextual effects for understanding the probability of childhood unvaccination for polio.

Multilevel model fit and specifications

We checked for multi-collinearity among explanatory variables examining the variance inflation factor (VIF),40 all diagonal elements in the variance-covariance (τ) matrix for correlation between -1 and 1, and diagonal elements for any elements close to zero. None of the results of the tests provided reasons for concern. Thus, the models provide robust and valid results. The MLwinN software, version 2.36, was used for the analyses.41,42 Parameters were estimated using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo procedure.41 The Bayesian Deviance Information Criterion was used as a measure of how well our different models fitted the data. A lower value on Deviance Information Criterion indicates a better fit of the model.43

Common- and special-cause variations

We generated scatter plots of performance, as a percentage, against the number of non-vaccinated children (the denominator for the percentage). The mean state performance and exact binomial 3 sigma limits were calculated for all possible values for the number of cases and used to create a funnel plot using the method described by Spiegelhalter.44,45 If a state lies with the 99% CI, it has crude unvaccination rate that is statistically consistent with the average rate (common-cause variation). If a state lies outside the 99% CI, then it has crude unvaccination rate that is statistically different from the average rate (special-cause variation).

Geographical mapping and variations

For conducting a GIS (geographic information system)-based analysis on the spatial distribution of non-vaccinated children for polio, the state-level polygon map was obtained, on which the state-level point layer containing information regarding latitudes and longitudes of central points of each county was created. All non-vaccinated children for polio were geocoded and matched to the state-level layers of polygon and point by administrative code. Spatial rate smoothing was performed using empirical Bayes approach. Smoothing geographically-defined data can uncover unexpected features, patterns, or gradients that one might not otherwise detect from a display.46,47 Geographically-defined data are often amenable to smoothing, since data in one region are likely affected, to a greater or lesser extent, by data in neighboring regions.46,47 Smoothing borrows neighboring information in a flexible way to permit exploratory analyses and provide indications of possible patterns that one might otherwise find difficult to detect.46,47,48,49 In addition, smoothing can reduce attention to unusual values or outliers.46,47,48,49 Based on prevalence of unvaccination for polio, all states were grouped into quartiles-based categories: low-prevalence area (1st quartile); medium-prevalence area (2nd quartile); high-prevalence area (3rd quartile); and very high-prevalence area (4th quartile). The 4 categories of state were color coded on maps. To assess the risk of polio non-vaccinated children in each state, an excess hazard map was produced. The map represents the ratio of the observed number of non-vaccinated children for each state over the expected number of non-vaccinated children. A likelihood function was used to test for elevated risk within the state in comparison with risk outside the state. The likelihood function for any given state was proportional to:

| (1) |

where D is the total number of non-vaccinated children, d is the number of non-vaccinated children within the state and n is the expected number of non-vaccinated children. The indicator function I() is 1 when non-vaccinated children in the state are more than expected; otherwise it is 0. The excess risk is a non-spatial measure, which ignores the influence of spatial autocorrelation.50

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

The Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) was used as a measure of the overall clustering and is assessed by a test of a null hypothesis51,52 Local measures of spatial association provide a measure of association for each unit and help identify the type of spatial correlation. The nature of spatial autocorrelation between states so they can be categorised into 4 groups:

-

•

High-high: high value of non-vaccinated children in a state, neighboring states have high values of non-vaccinated children (‘hot-spot').

-

•

Low-high: low value of non-vaccinated children in a state, neighboring states have high values of non-vaccinated children (spatial outliers).

-

•

Low-low: low value of non-vaccinated childrenin a state, neighboring states have low values of non-vaccinated children (‘cold-spot').

-

•

High-low: high value of non-vaccinated children in a state, neighboring states have low values of non-vaccinated children (spatial outliers).

After computing the appropriate statistic from the smoothed rates, a Monte Carlo Randomisation (MCR) procedure was used to recalculate the statistic from the randomized data observations to generate a reference distribution using 999 permutations. The p-values were computed by comparing the observed statistic to the distribution generated by the MCR process and significance level was set as .001. The Exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) was performed through the GeoDa software.53 GeoDa provides a very user-friendly environment to implement ESDA methods and is freely downloadable.54

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].WHO WHO Removes Nigeria from Polio-Endemic List Only 2 countries remain endemic to this paralysing disease. [url- http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/nigeria-polio/en/]. 2015. (accessed August26, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Roberts L. Infectious Disease. New polio cases in Nigeria spur massive response. Science (New York, NY) 2016; 353(6301):738; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.353.6301.738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].WHO Government of Nigeria reports 2 wild polio cases, first since July 2014. [url http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/nigeria-polio/en/]. 2016. (accessed August26, 2016.

- [4].Mehndiratta MM, Mehndiratta P, Pande R. Poliomyelitis: historical facts, epidemiology, and current challenges in eradication. Neurohospitalist 2014; 4(4):223-9; PMID: 25360208; https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1941874414533352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kandala NB, Magadi MA, Madise NJ. An investigation of district spatial variations of childhood diarrhoea and fever morbidity in Malawi. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62(5):1138-52; PMID: 16139938; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tanser FC, Le Sueur D. The application of geographical information systems to important public health problems in Africa. Int J Health Geogr 2002; 1(1):4; PMID: 12537589; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1476-072X-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health. National Routine Immunization Strategic Plan (2013-2015). Abuja, Nigeria: National Primary Health Care Development Agency; http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Nigeria/ri_strategic_plan_combined_mahmud_draft_1.pdf (accessed June 16, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health. 2017 Nigeria Polio Eradication Emergency Plan. Abuja, Nigeria: National Primary Health Care Development Agency; http://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NPEEP-2017-March-2017-FINAL.pdf (accessed June 16, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gidado S, Nguku P, Biya O, Waziri NE, Mohammed A, Nsubuga P, Akpan H, Oyemakinde A, Nasidi A, Suleman I, et al.. Determinants of routine immunization coverage in Bungudu, Zamfara State, Northern Nigeria, May 2010. Pan Afr Med J 2014; 18(Suppl 1):9. PMID: 25328628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mohammed A, Sabitu K, Nguku P, Abanida E, Sheidu S, Dalhat M, Dankoli R, Gidado S, Suleiman I. Characteristics of persons refusing oral polio vaccine during the immunization plus days - Sokoto, Nigeria 2011. Pan Afr Med J 2014; 18(Suppl 1):10. PMID: 25328629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Waziri NE, Ohuabunwo CJ, Nguku PM, Ogbuanu IU, Gidado S, Biya O, Wiesen ES, Vertefeuille J, Townes D, Oyemakinde A, et al.. Polio eradication in Nigeria and the role of the National Stop Transmission of Polio program, 2012–2013. J Infect Dis 2014; 210(Suppl 1):S111-7; PMID: 25316824; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/infdis/jiu199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chaix B, Guilbert P, Chauvin P. A multilevel analysis of tobacco use and tobacco consumption levels in France: are there any combination risk groups? Eur J Public Health 2004; 14(2):186-90; PMID: 15230507; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/eurpub/14.2.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chuang YC, Li YS, Wu YH, Chao HJ. A multilevel analysis of neighborhood and individual effects on individual smoking and drinking in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2007; 7(147):151; PMID: 17623053; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-7-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Duncan C, Jones K, Moon G. Smoking and deprivation: are there neighbourhood effects? Soc Sci Med (1982) 1999; 48(4):497-505; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00360-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Frohlich KL, Potvin L, Gauvin L, Chabot P. Youth smoking initiation: disentangling context from composition. Health Place 2002; 8(3):155-66; PMID: 12135639; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1353-8292(02)00003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Karvonen S, Sipila P, Martikainen P, Rahkonen O, Laaksonen M. Smoking in context - a multilevel approach to smoking among females in Helsinki. BMC Public Health 2008; 8:134; PMID: 18435839; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-8-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mathur C, Erickson DJ, Stigler MH, Forster JL, Finnegan JR Jr. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status effects on adolescent smoking: a multilevel cohort-sequential latent growth analysis. Am J Public Health 2013; 103(3):543-8; PMID: 23327273; https://doi.org/ 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull 2000; 126(2):309-37; PMID: 10748645; https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sampson RJ. The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspect Biol Med 2003; 46(3 Suppl):S53-64; PMID: 14563074; https://doi.org/ 10.1353/pbm.2003.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Merlo J, Chaix B, Yang M, Lynch J, Rastam L. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: linking the statistical concept of clustering to the idea of contextual phenomenon. J Epidemiol Commu Health 2005; 59(6):443-9; PMID: 15911637; https://doi.org/ 10.1136/jech.2004.023473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kawakatsu Y, Tanaka J, Ogawa K, Ogendo K, Honda S. Effects of Three Interventions and Determinants of Full Vaccination among Children Aged 12–59 Months in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Public Health 2015; 129(11):1530-8; PMID: 26278475; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Abuya BA, Onsomu EO, Kimani JK, Moore D. Influence of Maternal Education on Child Immunization and Stunting in Kenya. Matern Child Health J 2011; 15(8):1389-99; PMID: 20848172; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10995-010-0670-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shrivastwa N, Gillespie BW, Kolenic GE, Lepkowski JM, Boulton ML. Predictors of Vaccination in India for Children Aged 12–36 Months. Am J Prevent Med 2015; 49(6):S434-S44; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Subhani S, Anwar S, Khan MA, Jeelani G. Impact of Mother's Employment on Child Vaccination (A Case of Bangladesh). J Fin Eco 2015; 3(4):64-6 [Google Scholar]

- [25].Antai D. Gender Inequities, Relationship Power and Childhood Immunization Uptake in Nigeria: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Infect Dis 2012; 16(2):e136-e45; PMID: 22197748; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].iDMC Nigeria IDP Figures Analysis. [url http://www.internal-displacement.org/sub-saharan-africa/nigeria/figures-analysis]. 2016. (accessed August29, 2016 2016)

- [27].Callaway E. Smart shots bring Nigeria to brink of polio eradication. Nature 2015; 523(7560):263-4; PMID: 26178940; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/523263a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tienda M. Poor people and poor places: deciphering neighborhood effects on poverty outcomes In: Huber J, ed. Macro-micro linkages in sociology. Newbury Park, CA Sage Publication; 1991: 204-12 [Google Scholar]

- [29].Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001; 38(1):115-32; PMID:11227840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Montgomery MR, Gragnolati M, Burke KA, Paredes E. Measuring living standards with proxy variables. Demography 2000; 37(2):155-74; PMID: 10836174; https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2648118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Browne WJ, Draper D. A comparison of Bayesian and likelihood-based methods for fitting multilevel models. Bayesian Analysis 2006; 1(3):473-514 [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stegmueller D. How many countries for multilevel modeling? A comparison of frequentist and bayesian approaches. Am J Political Sci 2013; 57(3):748-61; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/ajps.12001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].NPC, ICF International Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, 2013-Final Report 10-6-2014 2014. http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR293-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm

- [34].Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: How to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan 2006; 21(6):459-68; PMID: 17030551; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/heapol/czl029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Griffiths P, Madise N, Whitworth A, Matthews Z. A tale of two continents: a multilevel comparison of the determinants of child nutritional status from selected African and Indian regions. Health Place 2004; 10(2):183-99; PMID: 15019912; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kravdal O. A simulation-based assessment of the bias produced when using as contextual variables in multilevel models. Demographic-Research 2006; 15(1):1-20; https://doi.org/ 10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- [38].Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis - an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- [39].Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 161(1):81-8; PMID: 15615918; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/aje/kwi017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tu YK, Kellett M, Clerehugh V, Gilthorpe MS. Problems of Correlations Between Explanatory Variables in Multiple Regression Analyses in the Dental Literature. Br Dent J 2005; 199(7):457-61; PMID: 16215581; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Browne WJ. MCMC Estimation in MLwiN v2.31. University of Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rasbash J, Charlton C, Browne WJ, Healy M, Cameron B. MLwiN Version 2.31. University of Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- [43].Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, Van Der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J Royal Stat Soc 2002; 64(4):583-639; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1467-9868.00353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Spiegelhalter D. Funnel plots for institutional comparison. Qual Saf Health Care 2002; 11(4):390-1; PMID: 12468705; https://doi.org/ 10.1136/qhc.11.4.390-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Spiegelhalter DJ. Funnel Plots for Comparing Institutional Performance. Stat Med 2005; 24(8):1185-202; PMID: 15568194; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/sim.1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kafadar K. Smoothing geographical data, particularly rates of disease. Stat Med 1996; 15(23): 2539-60; PMID: 8961462; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19961215)15:23%3c2539::AID-SIM379%3e3.0.CO;2-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kafadar K. Geographic trends in prostate cancer mortality: an application of spatial smoothers and the need for adjustment. Ann Epidemiol 1997; 7(1):35-45; PMID: 9034405; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00101-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Maude RJ, Socheat D, Nguon C, Saroth P, Dara P, Li G, Song J, Yeung S, Dondorp AM, Day NP, et al.. Optimising strategies for Plasmodium falciparum malaria elimination in Cambodia: primaquine, mass drug administration and artemisinin resistance. PLoS One 2012; 7(5):e37166; PMID: 22662135; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0037166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour RT, Haugh MC, Henry D, et al.. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Bmj 2004; 328(7454):1490; PMID: 15205295; https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Fang L, Yan L, Liang S, de Vlas SJ, Feng D, Han X, Zhao W, Xu B, Bian L, Yang H, et al.. Spatial analysis of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China. BMC Infect Dis 2006; 6:77; PMID: 16638156; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2334-6-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Anselin L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geo Anal 1995; 27:93-115; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Anselin L, Sridharan S, Gholston S. Using exploratory spatial data analysis to leverage social indicator databases: The discovery of interesting patterns. Soc Indicators Res 2007; 82(2):287-309; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11205-006-9034-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Anselin L, Syabri I, Kho Y. GeoDa: An introduction to spatial data analysis. Geo Anal 2006; 38(1):5-22; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.0016-7363.2005.00671.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Windows Gf GeoDA 0.9.5-i for Windows. http://geodacenter.asu.edu/software/downloads