Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the importance of considering both fidelity and adaptation in assessing the implementation of evidence-based programs.

Design/methodology/approach

The current study employs a multi-method strategy to understand two dimensions of implementation (fidelity and adaptation) in the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program. Data were video recordings of program delivery and pre-test and post-test interviews from the efficacy trial. Multilevel regression in Mplus was used to assess the impact of fidelity to the manual, coded by independent observers, on racial socialization outcomes. One activity on racial socialization, a core component of the program, was selected for an in-depth examination using conversation analysis (a qualitative method of analyzing talk in interactions).

Findings

Results of the quantitative analyses demonstrated that fidelity of the selected activity was associated with increases in parent’s use of racial socialization from pre-test to post-test, but only when participant attendance was included in the model. Results of the qualitative analyses demonstrated that facilitators were making adaptations to the session and that these adaptations appeared to be in line with cultural competence.

Research limitations/implications

The development of quantitative fidelity measures can be problematic, with many decision points to consider. The current study contributes to the evidence base to develop a quantitative measure of adaptation for family-based parenting programs.

Originality/value

Many researchers examining implementation of evidence-based programs consider fidelity and adaptation to be polar ends of a single spectrum. This paper provides evidence for the importance of examining each independently.

Keywords: Evidence base, Prevention, Programs, Parenting, Implementation, Fidelity, Adaptation, African Americans, Rural, Quantitative methods, Qualitative, Mixed method

Introduction

According to an extensive body of empirical research, evidence-based programs (EBPs) are effective in reducing a wide range of health outcomes (NRC/IOM, 2009), but only if these interventions are implemented well (Wilson and Lipsey, 2001). Recent meta-analyses (Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Dane and Schneider, 1998; Dusenbury et al., 2003) have concluded that high-quality implementation across a range of dimensions is necessary to achieve intended effects on program outcomes. These dimensions include fidelity or adherence to delivering all of the components as prescribed, quality of the teaching and interactive skill used to deliver the program, additive adaptations, or additions beyond the instructions in the program manual to meet the local context, and participants’ level of responsiveness, or enthusiasm and active engagement with the program. Despite these conclusions, research in the area of implementation is limited by inconsistencies in theory, definition, and measurement (Berkel et al., 2011b).

The field of prevention has emphasized a concern for the avoidance of Type III errors, which are those which conclude a program is ineffective, when poor results are actually due to poor implementation (Helitzer et al., 2000). Consequently, much attention has been given to ensuring that program facilitators deliver the program with high levels of fidelity, that is, implementing all of the components of the program as designed. Despite the fact that fidelity is the most widely accepted and examined dimension of implementation, the majority of intervention studies fail to report data on fidelity or link fidelity with outcomes (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). Of the nearly 500 studies examined in their meta-analysis on implementation, Durlak and DuPre found that only 59 studies assessed relations between fidelity and program outcomes, 76 percent of which found that they were positively related. Explanations in those studies with null results have emphasized lack of variability and sensitivity of measures. Another explanation is that the impact of fidelity is dependent on attendance, such that if the participants do not show up, facilitators’ behaviors within the session are essentially irrelevant (Hansen et al., 1991). Few studies have taken attendance into account when examining fidelity. A lack of specificity in the analyses linking fidelity with outcomes may also be a problem (Berkel et al., 2011b). Most studies consider the global influence of fidelity, sampled, and averaged across sessions, on a range of program outcomes. A more precise approach is to link those program outcomes with the fidelity assessed for the pieces of the program which target the respective outcomes (Berkel et al., 2011a).

In addition to the dangers of a Type III error, there is also the potential to conclude inaccurately that a program is successful, when the expertise of program facilitators may be driving program effects (Sobol et al., 1989). Facilitators frequently add material which they believe will increase the relevance, clarity, or utility for their participants (e.g. Dusenbury et al., 2005); this practice is referred to as adaptation. Research on adaptation provides information that can inform how programs should be implemented across different contexts, which is highly relevant as the field transitions from efficacy to effectiveness and dissemination research. Adaptation is also one of the most highly debated and rarely studied dimensions of implementation (Durlak and DuPre, 2008), perhaps in part due to adaptation’s historical categorization as the polar opposite of fidelity on a single continuum (Berkel et al., 2011b). Of the three critical implementation meta-analyses (Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Dane and Schneider, 1998; Dusenbury et al., 2003), only the most recent defined adaptation as distinct from fidelity. In contrast to the uni-dimensional view of fidelity and adaptation as polar opposites on a single continuum, others have argued that adaptation should be conceptualized as additions to the program, rather than simply a lack of fidelity (e.g. Blakely et al., 1987; McGraw et al., 1996; Parcel et al., 1991). Doing so enables the disentanglement of what might be a potentially valuable facilitator contribution to the curriculum from an inability to implement the program as designed. This argument is well supported, as all of the studies examining a link between adaptation (conceptualized as additions to the curriculum) and outcomes revealed positive associations (Durlak and DuPre, 2008).

Examining the influence of adaptation and fidelity in a single study provides insight into whether these constructs are in fact distinct and uniquely predict outcomes. Parcel et al. (1991) examined the influence of fidelity and adaptation (operationalized as “adaptation of the curriculum to meet student needs”) on gains in health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors as a result of participating in the Teenage Health Teaching Modules. Adaptation was associated with greater change in the targeted attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors than was fidelity. Moreover, among new facilitators, fidelity, and adaptation were each associated with increases in participant knowledge, while for more experienced facilitators, only adaptation predicted outcomes. Blakely et al. (1987) separated these components into three dimensions of implementation, namely fidelity, additive adaptations (additions to the program), and modifications (delivering a prescribed component, but changing it substantially). They found that the association between adaptation and outcome was of the same magnitude as the association between fidelity and outcomes. Moreover, because the two types of adaptation subscales (modifications and additions) were measured separately, the study was able to compare them. Modifications were not significantly associated with program outcomes. Additions to the program, on the other hand, accounted for improvements, above and beyond the influence of fidelity. Further, additive adaptations occurred more frequently in the context of high fidelity. Thus, it may be that skilled facilitators are able to implement the program as designed while simultaneously bringing in additional material to address the needs of participants in the local context.

In addition to negative conceptualizations of adaptation, another issue limiting its inclusion in implementation research is measurement. Fidelity assessments typically answer the question, “Did or did they not do what was in the manual?” Even this seemingly simple question has plagued researchers who have noted that it is not as straightforward as it seems (Perepletchikova et al., 2009). Adaptation answers, “what did they do?” and sometimes the even more important “why?” and “was it good or bad?” These questions are infinitely more challenging to answer and researchers have only recently begun to create measures to address these issues (e.g. Dusenbury et al., 2005; Hansen et al., 2011; Pankratz et al., 2011). So far, these measures have been used for programs in school settings. It is likely that the context of the intervention (e.g. school-based vs family-based or adult vs child participants) will be important in influencing the extent to which an adaptation is negative or positive.

One of the important questions to consider about adaptation is the influence of culture. It is generally accepted that cultural mismatch can undermine the effectiveness of EBPs (Botvin, 2004). As contexts change over time and as EBPs are offered to new and distinct populations, adaptation may be necessary to preserve program effects (Castro et al., 2004; Rogers, 1995), especially to the extent that components of the program are confusing, irrelevant, or in conflict with the new population’s situation or values (Emshoff et al., 2003). In explaining reasons for their adaptation, facilitators often cite the need to make programs fit the ecological niche in which they are working (Dusenbury et al., 2005; Ringwalt et al., 2004). As the field of prevention becomes aware of the need for culturally appropriate interventions, researchers have reflected about how to adapt programs in ways that make them more relevant for a given population. Two of the strategies that have been advocated are community-based participatory approaches (Israel et al., 2008; Minkler, 2004) and cultural matching of facilitators to participants (e.g. Wilson and Miller, 2003; Castro et al., 2004). Underlying each of these strategies is the assumption that community members, in the role of program co-designers or implementers, possess cultural expertise that may enable them to adapt the program to increase its relevance for the population (Brach and Fraser, 2000; Palinkas et al., 2009). An important distinction between these two strategies is that participatory approaches are planned, systematic, and under the direction of program designers. However, this approach can require financial resources and an extensive amount of time, and is not always able to accommodate rapidly changing contexts. Further, culture depends on the local level (i.e. within the intervention delivery setting), to which facilitators with a deep understanding about the local context are able to adapt quickly and specifically. Even with planned adaptations which involve the community, each program setting is unique and adaptations will continue to occur beyond this planning process (Castro et al., 2004). Failing to document these adaptations through careful study of implementation precludes generalizations about programs across settings (Boruch and Gomez, 1977) and sacrifices important information about what might make programs culturally appropriate in different contexts (Backer, 2002). Finally, the material added by facilitators may be either constructive or iatrogenic (Dusenbury et al., 2005). Thus, it is essential to develop systems to measure adaptations occurring in the field.

The current study examines fidelity and adaptation in the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program (Brody et al., 2004), a family-based preventive intervention to reduce adolescent substance use and sexual risk behavior in rural African American communities. The content of SAAF was developed through a decade-long program of strengths-based research on rural African American families and a collaborative partnership between researchers and community stakeholders (Murry and Brody, 2004). Specifically, it focusses on the development of positive parenting practices, including racial socialization, warmth, communication, and consistent discipline, that have characterized resilient families in a context marked by poverty and discrimination. These practices support children’s successful transition to adolescence, buffering them from the challenging circumstances they confront. In accordance with SAAF’s theoretical model, intervention-induced changes in racial socialization lead to an increase in children’s racial pride, body image, and values associated with risk behaviors (Murry et al., 2007, 2011). These protective factors, in turn, predict reductions in sexual risk behavior at the long-term follow up when children were 17 years old. Because racial socialization is pivotal to SAAF’s theoretical model, the implementation data presented in the current paper focus on SAAF Parent Session 6: Encouraging Racial Pride, and specifically, on Activity 6.2 which is designed to demonstrate different ways of responding to discrimination (see “Methods” for more details).

In the current study, we explore several research questions related to the implementation of the SAAF program:

RQ1. What was the range of fidelity to the curriculum as designed, at increasing degrees of specificity (i.e. on the whole, for the selected session (Session 6), and for the selected activity (6.2))?

RQ2. How did the fidelity, at increasing degrees of specificity, influence gains in racial socialization practices, the primary targeted outcome of this activity?

RQ3. Was the effect of fidelity, again at increasing degrees of specificity, dependent on participant attendance?

RQ4. How consistent were participant responses with the program definitions in this activity?

RQ5. What kinds of adaptations were made, especially when caregivers responded to the activity in a way that was inconsistent with the program’s definitions?

Methods

To address these questions, we applied a multi-method approach. First, associations between fidelity and racial socialization were assessed quantitatively through multilevel regression. Second, because we know little about how facilitators in a program designed to be culturally competent implement the curriculum in a way that respects the values and experiences of individual families, we employed conversation analysis (CA) to analyze transcriptions of videotaped. This enabled us to analyze interactions and examine how facilitators made adaptations made during delivery of the activity.

CA is a qualitative method of analyzing talk in interactions (Sacks, 1995; Ten Have, 2007). Founded in sociology, this method has been used widely for several decades across disciplines to study talk that occurs in both mundane and institutional settings. There is a robust body of literature that examines interaction in institutional educational and healthcare settings (e.g. McHoul and Rapley, 2001; Maynard, 2003; Llewellyn and Hindmarsh, 2010; Pilnick et al., 2010; Drew and Heritage, 1992; Heritage and Maynard, 2006; Hester and Francis, 2000).

SAAF program curriculum

Families meet for seven consecutive weekly sessions. After sharing a meal together as a group, youth and their caregivers (usually parents, but also grandparents and other extended family members) separate to attend their respective, hour-long concurrent sessions. Topics such as involved, nurturing parenting, and racial socialization are addressed in the caregiver sessions (led by one facilitator) through videotaped narration and vignettes and group discussions. Separate youth sessions (led by two facilitators) address goal setting, norms of risk behavior, and peer pressure resistance through a variety of games, activities, and role-plays. After the caregiver and youth sessions, families reconvene for an hour-long family session (led by the caregiver and youth facilitators), which consists of family discussions and games to reinforce weekly topics from the separate sessions.

SAAF Session 6: “Encouraging Racial Pride”

The curriculum promoted racial socialization and racial pride in many ways. For example, each caregiver, youth, and family session ended with the participants asserting a creed emphasizing racial pride. Throughout the sessions, caregivers and children discussed concerns and strengths specific to African American families. The sixth meeting of the program was exclusively devoted to dealing with discrimination and racial socialization. Caregivers discussed their experiences with racism and considered the implications of different approaches to dealing with racism for their children. Youth discussed and role-played different ways to deal with situations where they were treated unfairly. Families played a “Black Pride” board game, in which they worked together to answer trivia questions about famous African Americans and identify strengths of their communities.

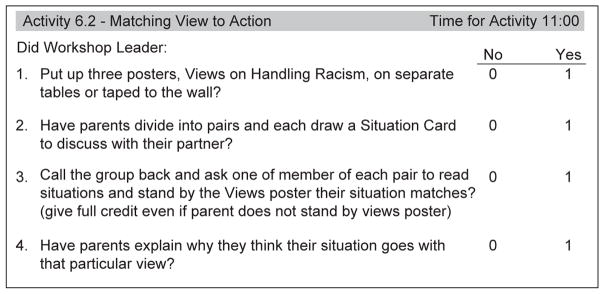

The current paper focusses on the implementation of one of these racial socialization activities, namely the Caregiver Session 6.2 activity, “Matching Views to Action,” in which caregivers discussed three approaches of responding to discrimination, the “Integrationist” (passive), the “Separatist” (aggressive), and the “Black Pride” (assertive) approaches (see Table I for definitions presented on the posters used within the session). The purpose of the activity was to familiarize caregivers with these three different approaches so that in the subsequent activity, they would be able to have a meaningful discussion about the consequences of each approach for their children. A video introduced the activity with two narrators explaining the three approaches. Next, facilitators displayed three posters with descriptions of each approach (Figure 1). Each caregiver received a card with one of 12 unique vignettes (see Table II). The first section of each card began with one out of four situations in which an African American child or caregiver experienced discrimination. The situations came from true accounts of experiences that community members shared during the design of the program. For each of the four situations, there were three possible responses which mapped on to the three approaches to dealing with discrimination (i.e. Separatist, Integrationist, or Black Pride). In pairs, participants discussed the situations and decided which of the three approaches matched the response on the card. Not all cards were addressed in the time provided and they were not discussed in any predetermined order. They then returned to the full group to read their cards, share which approach they believed the response reflected, and discuss the reasoning behind that decision.

Table I.

Definitions of “Views of Handling Racism” in the strong African American families program

| Integrationist | Separatist | Black Pride |

|---|---|---|

| Passive | Aggressive | Assertive |

| Teach children that all people are basically the same | Warn their children about other races | Have pride in being African American |

| Want to look and act like mainstream society | See the whole world as racist and unfair | Aware of racism and discrimination |

| Think others make too big of a deal about racism | Try to stay apart from other races | Act strong and assertive when dealing with racism |

Figure 1.

Excerpt from the SAAF Manual from Activity 6.2

Table II.

Discrimination vignettes

| Possible responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Integrationist | Separatist | Black Pride |

| Jay was waiting in her car in the line at the drive-through with her two children at a fast food chain. After she had paid for her food, the cashier, who was white, threw the sack of food at Jay and it fell onto the ground | Jay was upset but she told her children that the cashier was probably just having a bad day and she didn’t want to make a fuss. She picked up the bag and drove off | Jay picked up the sack, parked her car, and took her children into the fast food restaurant. She went behind the counter into the area where the cashier was and gave her a piece of her mind. When the cashier tried to explain, Jay turned to the manager and started calling him names | Jay picked up the sack, parked her car, and took her children into the fast food restaurant. She asked to speak to the person who had thrown the food at her but that person was disrespectful and rude and would not listen to her. Next, she asked to speak to the manager |

| Rosa was browsing in a department store looking for a shirt when the sales person came up and asked her if she needed help. When Rosa said she was just looking, the sales person, who was white, stayed in the same area and watched every move she made, following her from one rack to the other | Rosa was uncomfortable but she was afraid to say anything. She figured the sales person was just doing her job | Rosa stopped dead in her tracks and told the clerk, “Get out of my face, bitch. I should have expected to be treated this way by a person like you” | Rosa turned to the clerk and said, “when I need your help I will find you. Until then, I am just looking” |

| 15-year-old Robert comes home to tell his parents that the police were harassing him and his friends in front of the neighborhood convenience store. Robert says that they were not doing anything wrong, just talking and having a good time, but the police broke up the group and made them move on | Robert’s parents tell him that it’s probably not a good idea to hang out with his friends at that place – that he should probably just avoid going to that store | Robert’s father says, “That racist son-of-a-bitch. Whites are always out to get us and the police are the worst of the bunch. I’d like to punch him out” | Robert’s parents tell him that sometimes police do treat African Americans unfairly and talk with him about what he could do next time in a similar situation |

| 12-year-old Keisha came home very upset because of an incident that happened at school. The teacher had accused her of stealing some carnival tickets from her desk. Keisha told her mama that she had nothing to do with it and, in fact, she had seen one of the other kids, who was white, take the tickets | Mama told her, “Well you have to understand how busy teachers are. They have so much to deal with and I’m sure she didn’t mean anything by it” | Mama said, “That’s just like those White teachers to accuse a Black child. This is what you expect. Stay away from those Whites whenever you can. I’m going to give her a piece of my mind!” | Keisha’s mama asked her for some more details about what happened and told Keisha she would got to the school tomorrow to meet with the teacher and the principal |

A critical component of culturally appropriate programs is respect for participants’ lived experiences (Cross et al., 1989). SAAF promotes the idea that all families have their own values by which they make decisions about what is best for their families. On the other hand, the foundational research guiding the program demonstrates an advantage for African Americans who follow the “Black Pride” approach, where discrimination is recognized and handled assertively (Hughes, 2003). Without explicitly telling participants how they should respond to racism, the curriculum is designed to provide caregivers the opportunity to consider costs and benefits of the different approaches. Program designers formulated the curriculum to achieve this goal by labeling and categorizing the approaches and encouraging caregivers to think about the consequences for children in vignettes. However, as with all program implementation, it is dependent on individual facilitators to implement the curriculum according to the framework in which it was created (Ringwalt et al., 2004). Rough measures of fidelity allow for an understanding of whether the facilitator implemented the main components of an activity, but they do not demonstrate how facilitators interacted with participants or what additional material may be added. Because the activity “Encouraging Racial Pride” is somewhat difficult conceptually, and of a sensitive nature, it is essential to understand the interaction that occurs between facilitators and caregivers, especially when caregivers provide an answer that is inconsistent with the position promoted by the program.

Program participants

African American primary caregivers with 11-year-old children were recruited from school rosters in nine counties in rural Georgia. These counties ranked amongst the highest for poverty in the country (Dalaker, 2001). From these rosters, 521 families were randomly invited to participate and 332 agreed to participate, resulting in a recruitment rate of 64 percent. Almost half (46.3 percent) of the participating families’ household incomes were below the poverty threshold (average of =$1,655 per month), despite having completed high school (78.7 percent) and working almost full time (average of =39.4 hours). These rates are representative of families in this area (Boatright and Bachtel, 2000).

Program facilitators

Hiring criteria for program facilitators was being African American, having prior experience in working with adolescents or families, and having grown up in communities similar to those served by the SAAF program. Facilitators were trained on the manualized curriculum over the course of four full days. During this training, they observed the delivery of the program activities, learned about the theory guiding the program, and practiced delivering sections of the curriculum to their peers and supervisors. Before implementing the program, they demonstrated mastery in delivering the content of the selected sections. For the caregiver groups included in the current study, ten facilitators led between one and three groups each. Eight facilitators were female and two were male.

Video data and transcriptions

Sessions of SAAF were digitally videotaped for the purposes of conducting implementation assessments. As previously mentioned, CA was used to analyze the interactions between facilitators and participants. CA is examines fine-grained details of talk-in-interaction, including turn-taking, sequential structure, and the actions accomplished by speakers through talk and non-verbal interactions, like pauses (Pomerantz and Fehr, 1997). Consequently, what is gained in depth must be sacrificed in breadth. For the current paper, we take an in depth examination of recordings and materials from Caregiver Session 6: “Encouraging Racial Pride,” Activity 6.2: “Matching Views to Action.” This activity was selected for analysis because of the very relevant, yet sensitive nature of the discussion of how to handle discrimination.

While the curriculum was designed to be responsive to the values of participants, the goal of cultural competence requires that facilitators also use empathy and skill so as not to condemn or alienate caregivers whose experiences result in responses to racism that may run contrary to the suggested approach. Being African American and from similar communities may provide facilitators with a similar cultural frame of reference and experiences from which to draw; however, this is not guaranteed. Observations of this activity allow for an examination of the strategies facilitators drew on to encourage processing of the program material in a way that respected families’ lived experiences.

Across the first cohort of SAAF (n =20 groups), all introductions and 91 vignettes that were discussed as part of Activity 6.2 were selected from digital video recordings of program sessions. Segments were downloaded using Windows Movie Maker 5.1. Video recordings are a strength of this study and are a form of data that is becoming prevalent in CA for many (Heath et al., 2010). Primarily, recordings are preferable to data sources such as field notes because data become part of the permanent record, available for verification by future researchers. Because reliability in qualitative research can be thought of as the extent to which another researcher would come to similar conclusions if the study was conducted again in the same way, this adds to the study’s credibility (Peräkylä, 2004). Second, much of CA depends on a “second-turn proof procedure,” interpreting the meaning of a prior utterance by the way other participants respond to it. MacMartin and LeBaro (2006) suggest that this type of analysis is useful in the sense that it provides some indication about how parties to the interaction demonstrate (e.g. through gaze, bodily movement, or gesture) how they have analyzed ongoing talk relative to their own agendas. Video data provides visual cues through which reactions to the initial talk can be studied concurrently. Third, video data also enhances analysis by allowing for the consideration of body language that, paired with utterances, provides additional layers of meaning to what was said (MacMartin and LeBaro, 2006). Of course, the advantages of video data are limited by what is visible on-screen, depending on the view of the camera.

Sequences were transcribed according to Jeffersonian conventions (Psathas and Anderson, 1990). These conventions result in a much more fine-grained transcript than do those conducted for a thematic analysis (see Table III). Because they convey meaning within interaction, CA transcripts capture the paralinguistic features of talk, such as repetitions, breaths, and intonation, and when possible, visual information (Pomerantz and Fehr, 1997), often neglected in traditional transcripts. Moreover, as video data are becoming more widely used within CA (Heath et al., 2010), transcription conventions are expanding to include physical interactions. The current study situated actions and physical descriptions (e.g. direction of gaze, the use of props, and gesturing) within the transcriptions, which were organized in tables for clarity. Tables also included an analysis column for recording the characterization of actions accomplished during the talk.

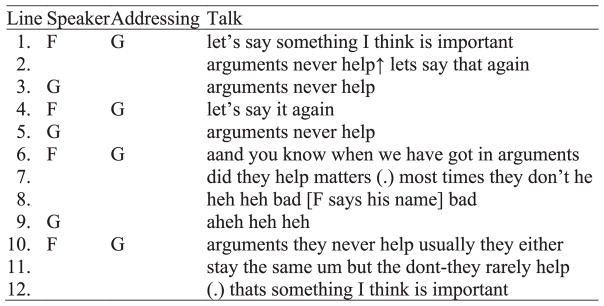

Table III.

Transcription conventions

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| F | Facilitator |

| P1 (etc.) | Parent 1 (etc.) |

| G | Whole group |

| (.) | Pause |

| heh heh ha hah | Laughter |

| underlining | Emphasis |

| ↑ | Upward intonation |

| ↓ | Downward intonation |

| [ | Overlapping speech |

| [ | |

| = | No pause between turns |

| ∘ | Low volume |

An undergraduate psychology student conducted initial transcriptions of half of the vignettes, which the first author refined to produce more detailed transcripts. The remaining half was transcribed entirely by the first author.

Quantitative measures

Fidelity

Fidelity is defined as the amount of content prescribed in the program manual that was covered by program facilitators. The development of fidelity measures is not a straightforward process. Decisions must be made as to the level of detail in fidelity items. Micro-level codes assess more concrete actions and thus facilitate inter-rater reliability. An example of a micro-level fidelity item is, “did the facilitator put up the three posters?” Macro-level codes are at a more abstract level, possibly providing a more externally valid assessment of whether the point of an activity was conveyed. However, these types of codes include a higher level of interpretation, deterring inter-rater reliability. An example of a macro-level fidelity item is, “did the facilitator teach the group about different ways of handling racism?” For the SAAF fidelity measures, it was decided to create questions at a more “micro” level to assess concrete behaviors, adding to the rigor of the assessment. Instruments for coding fidelity were created based on the SAAF program manual. Most actions described in the manual were turned into an item with either a yes/no response. Some items included a partial completion or a count when appropriate. The score was calculated as the total number of fidelity items completed divided by the total possible and multiplied by 100 to get a percent. Multiple coders (including the first author) observed video recordings of the program sessions to assess the extent to which facilitators covered the points outlined in the material. Double coding 20 percent of the videos, these coders reached an inter-rater reliability of 80 percent. In the current study, we employed the fidelity scores for the program on the whole (based on an average across sessions), the fidelity scores for Session 6 only, and the fidelity scores for Activity 6.2 in Session 6.

Attendance

Caregiver attendance was dummy coded for each session as a 0 for absent and a 1 for present.

Program outcome: racial socialization

African American interviewers received 27 hours of training in the administration of the computer-based research protocol. Pretesting occurred one month before sessions began, before group assignment to intervention (n =157) or control (n =127) conditions. Posttesting began three months after the program, producing a seven-month interval between pretest and posttest. Primary caregivers provided informed consent for themselves and adolescents at each assessment. Adolescents also provided assent. All interviews were conducted with adolescents and caregivers in the families’ homes and lasted approximately two hours. To reduce literacy concerns, interviewers read aloud self-report questionnaires that were displayed, one item at a time, on laptop computers that both the interviewer and the participant could see. Interviews were conducted privately with no other family members able to overhear. Families were compensated $100 at each data collection point.

Caregiver report of racial socialization was assessed via the racial socialization scale (Hughes and Johnson, 2001) at the pretest and posttest. The measure includes 15 items, rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 3 (three to five times), concerning the frequency with which caregivers engaged in specific racial socialization behaviors during the past month. These behaviors included talking with children about the possibility that some people might treat them badly or unfairly because of their race, talking to children about important people or events in African American history, and doing or saying things to encourage children to learn more about African American history or traditions. Cronbach’s α’s at both waves exceeded 0.75.

Analytic plan

Because families were nested within intervention groups, to examine the impact of fidelity (at the group level) on racial socialization outcomes (at the participant level), it was necessary to use multilevel modeling, which was conducted in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2010). As this study examines the impact of implementation, participants randomly assigned to the control condition were excluded. First we used an intent-to-treat model, with all participants in the intervention condition were included in the analyses. We examined impact of fidelity scores on posttest racial socialization, controlling for pretest scores. Analyses were conducted repeated the analyses three times to examine the impact at increasing degrees of specificity: overall, with fidelity scores averaged across all sessions, for the session on racial socialization, with fidelity scores for Session 6, and for the activity on responding to discrimination, with fidelity scores for Activity 6.2. Because including participants who were not exposed to the delivery can falsely dilute the effects of fidelity, we repeated these analyses and added the effect of attendance. In the first analysis, dummy coded attendance scores for each session were multiplied by the fidelity score for each session to create an exposure × fidelity score for each session. Then these scores were averaged across sessions to produce an overall score. For the second and third analyses, attendance at Session 6 was multiplied by the fidelity score for the session and the activity, respectively. Missing data were handled with full information maximum likelihood. Multiple practical fit indices (χ2, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR) were used to evaluate the extent to which the model fit the data because no single indicator is unbiased in all analytic conditions. Model fit was considered good if the χ2 was non-significant or the SRMR≤0.05 and either a RMSEA≤0.05 or a CFI≥0.95 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). R2 was used to determine the level of variance accounted for.

CA was employed to analyze the interactions between facilitators and participants and obtain an in-depth understanding of facilitators adaptations, defined as content or strategies that facilitators used that were not prescribed in the manual. The first step of the analysis process was to review each transcript successively. A line-by-line analysis within each transcript allowed for the characterization of the actions accomplished in each actor’s turn. Coding focussed specifically on the actions accomplished through facilitators’ speech. These actions were coded for adaptations, with special attention to when material was added to the curriculum in terms of methods or content. Participant speech was also coded to provide context for facilitator actions. A CA study group, as well as two caregivers who were unaffiliated with the SAAF program, but who had African American adolescent children, participated in data sessions, giving feedback about study analyses.

Results

Fidelity

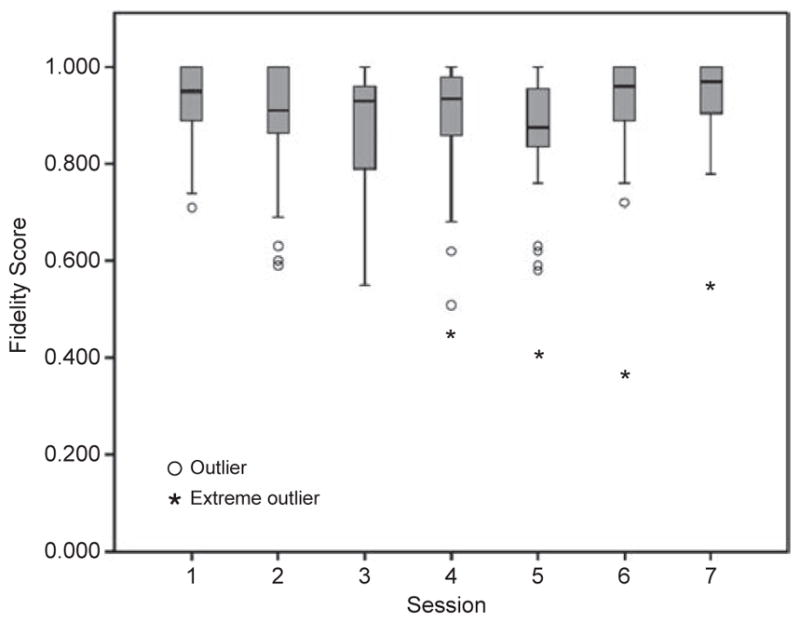

Range of fidelity

Across the seven caregiver sessions, fidelity scores ranged from 40 to 100 percent, with a mean of 88 percent (SD =14 percent). As displayed in Figure 2, Session 6 had among the highest fidelity scores and the lowest variability. However, for the four fidelity items within Activity 6.2: “Matching Views to Action,” fidelity ranged from 50 to 100 percent, with a mean of 81 percent (SD =17 percent).

Figure 2.

Fidelity ratings across parent sessions

Influence of fidelity on program outcomes

The next set of analyses assesses the impact of fidelity on changes from pretest to posttest in caregivers’ racial socialization practices. In assessing the impact of overall fidelity, without accounting for attendance, fit indices provided support for model fit (see Table IV), however, average fidelity scores did not significantly predict increases in racial socialization from pretest to posttest. Comparable results were found when examining the impact of Session 6 fidelity, as well as the impact of fidelity exclusively within Activity 6.2.

Table IV.

Impact of fidelity on racial socialization outcomes

| Model fit indices | Fidelity on post-test racial socialization scoresa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2(df =1) | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | ||

| Intent-to-treat | |||||

| Overall program fidelity | 1.2, p>0.1 | 0.02 | 0.998 | 0.02 | −0.02, p>0.1 |

| Session 6 fidelity | 0.9, p>0.1 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.00, p>0.1 |

| Activity 6.2 fidelity | 0.8, p>0.1 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.00 | −0.08, p>0.1 |

| Accounting for attendance | |||||

| Overall program fidelity | 1.2, p>0.1 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.07, p>0.1 |

| Session 6 fidelity | 0.7, p>0.1 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.10, p≤0.001 |

| Activity 6.2 fidelity | 0.1, p>0.1 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.19, p≤0.001 |

Notes:

Standardized β; controlling for pre-test racial socialization scores

Influence of fidelity and attendance on program outcomes

In the next set of analyses (see Table IV), attendance was taken into account by multiplying the dummy coded attendance variable for each session by the appropriate fidelity score. An average across sessions was taken to assess the impact of the overall fidelity, and again, while fit indices provided support for the model fit, average fidelity scores were not associated with gains in racial socialization. However, in a model examining the impact of fidelity scores for Session 6, which specifically dealt with the targeted outcome, exposure to high fidelity significantly predicted increases in racial socialization from pretest to posttest. Moreover, assessing fidelity specific to Activity 6.2 resulted in positive fit indices, and a significantly link between exposure to fidelity and posttest racial socialization, controlling for pretest scores. The amount of variance in posttest racial socialization scores accounted for the model with attendance included and fidelity specific to activity 6.2 was 30 percent. Without attendance, R2 went down to 13 percent.

Consistency between program definitions and participant responses

Participants’ responses in the activity were examined to determine whether they were consistent with the program’s definition (see Table V). Vignettes with “Black Pride” reactions to discrimination were the most straightforward for participants, with a concordance rate of 79 percent. “Integrationist” vignettes were identified as such by participants 65 percent of the time. In the discrepant cases, “Integrationist” vignettes were more likely to be identified as “Separatist” than “Black Pride.” The vignette responses which appeared to be most problematic in achieving agreement between program definitions and participant understandings were those designed to reflect the “Separatist” viewpoint, with an agreement rate of only 50 percent between program definitions and participant responses. Of the 14 discrepant responses, 79 percent were viewed as “Black Pride” and 21 percent as “Integrationist.”

Table V.

Participant responses to the vignettes in Activity 6.2

| Curriculum-defined answer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Pride (assertive) | Integrationist (passive) | Separatist (aggressive) | Total | |

| Participant response | ||||

| Black Pride | 23 (79%) | 4 | 11 | 38 |

| Integrationist | 3 | 22 (65%) | 3 | 28 |

| Separatist | 3 | 8 | 14 (50%) | 25 |

| Total | 29 | 34 | 28 | 91 |

Sources of trouble and facilitator adaptations

Although fidelity in Session 6, and especially in Activity 6.2, played a significant role in increasing caregivers’ racial socialization, it fell short of completely explaining the change from pretest to posttest. Further, discrepancies between program definitions of the responses to discrimination and the caregivers’ responses indicated a need to better understand the interactions in this activity, in terms of participants’ understandings and facilitators’ adaptations. Using CA, we probed video transcripts to explore the interactions that occurred during the activity, with special attention to what was added beyond manual instructions. Results suggested that facilitators added methods or content to the program when participants experienced difficulties with the activity. Analyses across the transcripts pointed out consistent areas of trouble, which were marked by questions, pauses, and back and forth interactions where participants and facilitators attempted to make sense of the activity, referred to as “repair” in the CA literature (Schegloff et al., 2002). In the sections that follow, we present these interactions, focussing on sources of trouble and facilitators’ adaptations to increase participant understanding.

The first source of trouble within the talk was confusion about whose actions the activity was designed to evaluate. Each situation card shared the actions of at least two parties, a person or group committing an act of discrimination and an African American caregiver responding to the situation. Confusion was present when participants attempted to evaluate the act of discrimination, as opposed to the caregiver’s response to that situation. It was not the point of the program to say that discrimination should not be examined, but to emphasize that those experiencing discrimination can only be responsible for their own reactions to the situation. For example, in Group 20 (Jay-Black Pride), Participant 5’s initial answer (Separatist) was divergent from the program’s definition (Black Pride). After the facilitator asked her why she chose that response, the participant backtracked and asked for clarification as to whose behavior they were supposed to be interpreting. As was typical in the data, once clarification was provided (either by facilitators or other participants), the participant corrected her response. In two other groups, facilitators avoided confusion by modeling the activity before the participants engaged in it.

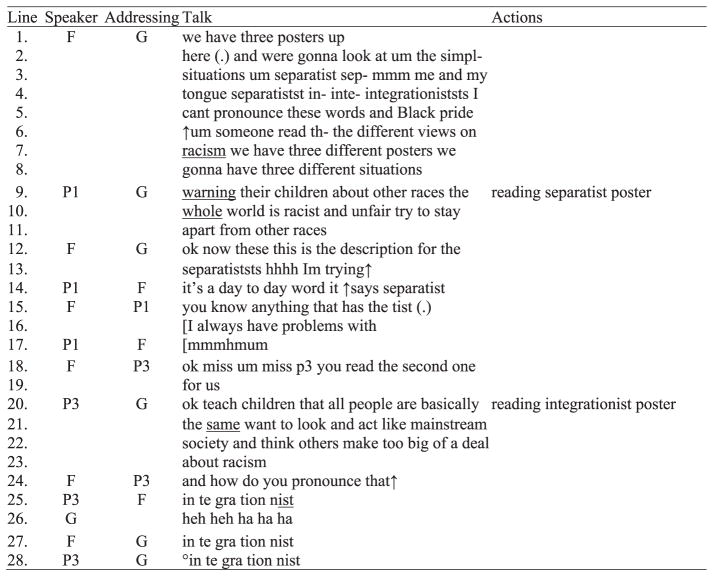

A second source of trouble was the difficult terminology employed in a context where many of the parents had limited literacy. In accordance with the manual, facilitators partnered non-reading caregivers with caregivers. This was not assessed as part of fidelity for two reasons: first, it was conditional on having limited readers in the group and second, a coder might be unaware of this action or the reason behind it. Beyond partnering, the manual did not direct facilitators in how to manage the activity for non-readers. Unscripted ways facilitators assisted with limited literacy were by reading, or having another caregiver read, the definitions on the posters aloud (rather than simply posting them) and by asking the partner with higher literacy to read both of the cards that the pair had discussed. In some groups, the facilitator identified the terms “Integrationist” and “Separatist” as problematic. For example, in the activity’s introduction in each of the three groups that one facilitator led, she mispronounced these labels and apologized repeatedly for her difficulties (see Figure 3, Lines 3–5, 13, 15–16). Caregivers critiqued the facilitator’s struggle with the terms in a tone that could be perceived as condescending (Lines 14; 25–28). It appeared that this mispronunciation may have been intentional because, later in each of these three groups, she pronounced the terms effortlessly and assisted others who struggled with them.

Figure 3.

Difficult terminology (Group 9, instructions)

The fact that “Integrationist” vignettes were more likely to be identified as “Separatist” than “Black Pride” appeared to be due to everyday usage of the term “separate” and was especially apparent with the Robert-Integrationist situation card. Six out of the 12 discrepant cases for the Robert cards occurred when participants interpreted the Robert-“Integrationist” approach as “Separatist.” In the Robert vignette, the police had Robert vacate a store where he and his friends were innocuously congregating. On the “Integrationist” version of the card, Robert’s parents responded by telling him to avoid going to the store in the future. This vignette was considered “Integrationist” by the program because it depicted caregivers who taught their child to ignore the racial undertones of the situation and to relinquish his right to frequent what may have been the only store in his community. On the other hand, many participants with the Robert-“Integrationist” card used a common sense understanding of the word “separate,” meaning to stay apart from, and answered “Separatist.” In discussing the Robert-”Integrationist” card in Group 13, the facilitator asked P4 for reasoning as to why she responded “Separatist.” P4 responded, “because she was trying to tell to separate and they just not go to that place and stuff.” This account served to define not the curriculum-defined meaning of “Separatist” (as on the poster), but the everyday definition of what the word “separate” means, as in “stay apart from.” In response, the facilitator formulated the talk, adding to this definition by providing possible reasoning as to why one would separate from others: “the world is unfair (.) maybe you shouldn’t hang around with them (.) ok↑.”

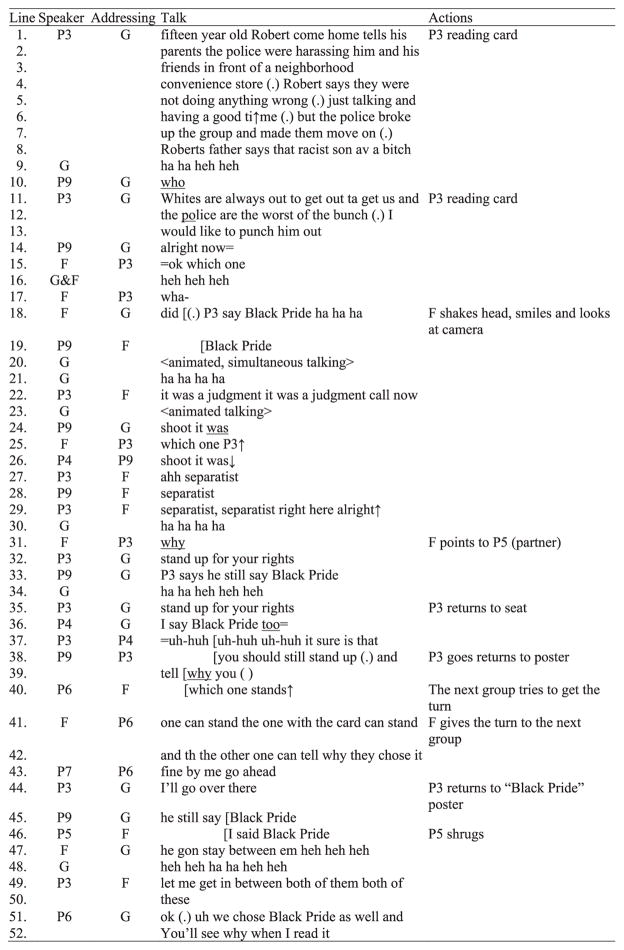

When participants responded to “Separatist” vignettes as “Black Pride,” the following conversations were typically characterized by dynamic, simultaneous talk, and the use of change-of-state tokens (Heritage, 1984), such as “ooohs” and laughter on the part of the group as a whole, which often marks sensitive topics and ambiguity (Haakana, 2001; Jefferson, 1984). An example of this ambiguity is presented in an extended sequence in Figure 4, in which the facilitator and participants laughed in response to P3’s “Black Pride” answer. P3 reasons that it was a judgment call; however, the reason for the ambiguity was never explicitly stated. The laughter and unexplained ambiguity characterizes the interaction as an insider’s joke, which the facilitator was clearly in on. P3 received support for his interpretation from other participants (Lines 33, 36, 46, and 51). This solidarity around interpreting this vignette as “Black Pride” was not disputed by the facilitator. Finally, the facilitator tried to give the turn to the next group, but P3 retained his turn by returning to the poster. The facilitator laughed at his persistence and then P6 succeeded in taking the floor with the next turn.

Figure 4.

Ambiguity of Separatist vs Black Pride (Group 13, Vignette 3, Robert-Separatist)

Directions for how to evaluate participants’ answers were not prescribed in the manual or assessed as part of fidelity. Facilitators often avoided providing an evaluation of participants’ answers, especially when participants’ answers disagreed with the curriculum-defined answer. Research on assessments in conversational talk has found that negative evaluations are preceded by extended pauses or turn prefaces, marking them as dispreferred or problematic actions compared to positive assessments, which are generally accentuated and stated directly with minimum or no delay (Pomerantz, 1984). Similarly, facilitators employed a variety of strategies to avoid explicitly disagreeing with participants’ answers. This is unsurprising, since conversation analysts have found that the preference structure of talk is designed to “maximize cooperation and affiliation and to minimize conflict in conversational activities” (Pomerantz, 1984, p. 55). Many times, facilitators would simply give the turn to speakers in the next group; omitting any assessment of participants’ answers. In other cases, facilitators would not dispute the answer, but would point out what was similar between caregiver answers and the program definitions. In Group 15’s discussing of the Jay-“Separatist” card, P4 reasoned the card demonstrated “Black Pride” because “they went in there and gave ‘em a piece of their mind about throwing the food on the ground.” The facilitator redefined the P4’s answer as “handling the situation,” which is characteristic of the “Black Pride” response. The facilitator then integrated another common strategy, asking for consensus from the group. This strategy was generally ineffective as caregivers rarely disagreed with their peers. In this case, P6 asked for clarification as to what the answer was, to which the facilitator hedged by saying there is no right or wrong answer.

Another strategy facilitators commonly used to resolve disagreements was to compare and contrast the different ways of responding to the same opening situation. In Group 2, P4 classified Robert’s father’s “Integrationist” response to discrimination as “Separatist.” The “Separatist” card had already been discussed by another pair (P1 and P2). The facilitator compared the “Integrationist” response to the previous “Separatist” response: “remember their situation and how that hit-how that child’s father handled that and called them a racist sonnafa you-know-what.” P4 then held her ground, by invoking the everyday use of the term “separate.” With assistance from P1 and P2, the facilitator clarified the differences between the perspectives.

In delineating the differences between perspectives, especially between “Black Pride” and “Separatist” (the most commonly confused responses), facilitators and participants invoked language related to moral reasoning. This technique typically pitted what you should do (represented as Black Pride) with what you want to do (represented as Separatist). In Group 17, the facilitator introduced the moral implications of each response type in the instructions for the activity by sharing her hopes and expectations for caregivers’ behavior. She said:

[…] ok we’ve got the three different types separatist (.) which I’m sure none of y’all are like that (.) integrationist (.) sometimes we be a little bit like that sometimes and Black pride (.) which I’m sure we all ah-are really good with that.

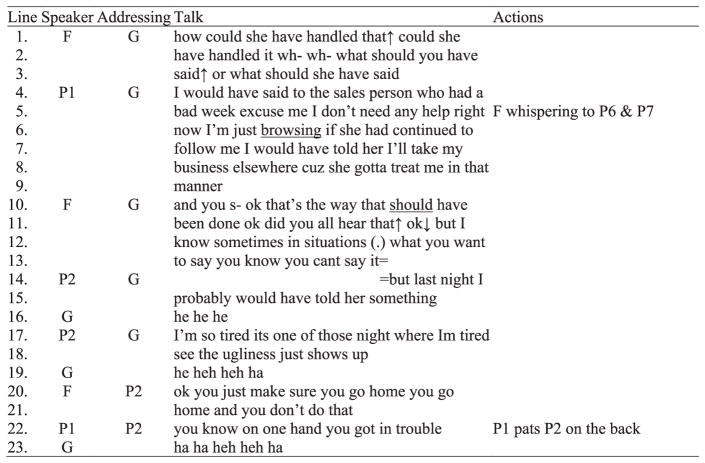

In Group 6, the facilitator moved the discussion beyond labeling the responses to brainstorming about “better” ways to handle discrimination (Figure 5). In Lines 10–12, the facilitator acknowledged the challenge in maintaining a “Black Pride” approach. P2 agreed by sharing how difficult it is when she is tired (Lines 14–18). In Lines 20–21, the facilitator admonished her to just go home in those situations. In Group 1, the facilitator normalized this common experience as a personal struggle she had also faced, but framed it in the past tense, as something that had been overcome: “I’ve done that before I used to be bad about it.” Her sharing inspired participants to share their own ideas about ways to positively deal with discrimination.

Figure 5.

Better ways to handle discrimination (Group 6, Vignette 1, Rosa-Separatist)

Facilitators picked up on participants’ anger in response to discrimination. They used “mini-lectures,” or what might be referred to here as “mini-sermons,” on a variety of topics to encourage caregivers to take the high road when faced by discriminatory situations. Some facilitators attempted to create understanding by pointing out how the family of origin acts as a socializing agent in transmitting racist attitudes. Other culturally based topics were to call on a higher power for strength or remembering Dr King’s teaching of non-violence: “it’s like uh what Dr King always says […] nonviolence that’s what I’m trying to say,” to which participants responded positively with their own ideas. Many facilitators brought up examples of self-talk that participants could use to remain calm in confronting discrimination. In Group 6, the facilitator makes three attempts to correct confusion about the Keisha-”Separatist” card by asking, “what you are supposed to do though” and “what is the right way.” After this attempt was unsuccessful, she offered examples of self talk to practice restraint:

[…] cuz we can’t always say cuz sometimes you’ve gotta bridle your tongue and you wanna say I’m a better person than that I got more pride in myself just because you acting that way doesn’t mean I have to act that way.

In response, P2 makes of extended demonstration of her self-improvement which seems to be directed at teaching P1 the difference between how she currently is and what she should aspire to in the future:

[…] but see you gotta use that self control to that because when you go to the school you gotta say a little prayer you gotta say and hell bridle your tongue and you won’t say no thing cuz some of that stuff I used to do↑ if I do that before I go up there I’m a better person but you know back a couple years ago now I ain’t gonna lie to you I could get ugly

It was common for caregivers to unabashedly claim their previous indiscretions in this manner, and as was typical, the group laughed in understanding. The facilitator made a point to reinforce the high ground by leaning over the desk toward P2 and saying, “I’m so glad you do I’m so glad you bridle your tongue.”

The most notable use of self talk was throughout the activity in Group 14. At the beginning of the activity (Figure 6), the facilitator recited a piece of self talk (arguments never help), and invited the participants to say it with him several times in a call-and-response format reminiscent of interactions in the Black church. This simple phrase, which was repeated throughout that group’s activity, served to drive home the message that racism must be addressed, but that it can be handled in a way that supports one’s dignity and self-respect while deescalating conflict and the negative consequences that can occur. The facilitator reminded the group of the phrase after the final participant’s turn. To which one of the caregiver’s responded by sharing a story of an acquaintance who had reacted with a “Separatist” response that the caregiver defined as “reflex.” Through an animated and entertaining presentation on the facilitator’s part, which included humorous pantomime, the group came around to agreement on the point that while it is challenging to remain calm, and stressful situations will arise sometimes at the most inopportune times, handling the situation calmly is what has to be done. By the end of the activity, the facilitator needed to simply wave his hands and the group would testify, “arguments never help.”

Figure 6.

Call and response (Group 14, instructions)

Discussion

Preventive interventions have demonstrated powerful effects across a wide range of outcomes and populations (NRC/IOM, 2009), yet they only produce these effects to the extent that they are implemented well (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). Between the design of a program and its implementation by program facilitators, there is infinite room for variability. Fidelity is the most commonly examined dimensions of implementation and most (but not all) studies analyzing the association between fidelity and outcomes have uncovered positive effects. However, limiting implementation assessments to whether or not facilitators completed the actions prescribed in the manual neglects a substantial part of the delivery. It is necessary to also examine adaptations that facilitators bring to the table based on their experience and expertise. When programs are implemented with new populations, cultural matching of facilitators with participants can be used as a strategy for supporting cultural relevance. In this case, examining adaptations is especially important, both to examine the nature of adaptations, which can be positive or iatrogenic, and to acquire information that can be used for refining the program in future iterations. Further, beyond the facilitators’ implementation practices, it is also important to consider the nature of participants’ engagement. Clearly, if participants do not attend, it cannot be expected that implementation will affect their outcomes. Examining the participants’ responsiveness to the facilitators’ implementation can also inform whether attempts at engaging them are appropriate and effective.

Impact of fidelity

Results of the quantitative analyses had important implications for the study of fidelity in EBPs. As hypothesized, there was no effect of fidelity without taking into account participant attendance, yet most studies of fidelity do not account for attendance (see Hansen et al., 1991 for an exception). Further, taking a global approach to assessing fidelity was a poor predictor of outcomes, whereas the more specific assessments lead to significant associations. Implementation assessments in most EBPs are based on a sampling of sessions or activities within sessions and the average is taken to examine the influence on outcomes. Evidence in the current study suggests the need to conduct outcome specific analyses, where program outcomes are linked to implementation of the specific components of the program which target that specific outcome. The increasing effect of fidelity with increasing levels of specificity supports the hypothesis that this activity is theoretically important for achieving program effects on racial socialization. Failure to consider attendance and lack of specificity may both be reasons for some of the null findings in the fidelity literature (Berkel et al., 2011b). Each of these practices is also important for understanding the theoretical underpinnings of the program and producing strong claims about causation.

Types of adaptations

Quantitative analyses confirmed the theoretical importance of Activity 6.2 to the conceptual model guiding the SAAF program. Qualitative analyses revealed the sensitive, and at times confusing nature of the activity, through the extended discussions that went beyond the manual, talk about moral judgments, and facilitators’ artful resolution of confusion (see Table VI). The study of adaptation is critical in making claims about the efficacy of the program. Some researchers have made very important gains in developing measures of adaptation, which are much more complex than fidelity assessments (e.g. Hansen et al., 2013). These measures have been used in school-based programs with children. It is likely that the types of adaptations made and whether those adaptations may be positive or negative in promoting engagement and supporting program outcomes may vary greatly across different contexts. The SAAF program was the first EBP developed for African American families in the rural south. Consequently, we elected to conduct qualitative analyses to understand the types of adaptations that might occur in this setting with unique stressors, strengths, and cultural conventions.

Table VI.

Summary of qualitative findings

| Sources of trouble | Facilitator strategies |

|---|---|

| Target of activity | Clarification from facilitator or from other participants |

| Difficult terminology | Modeling activity |

| Everyday usage of terms | Affected pronunciation |

| Reformulation of participant responses | |

| Linking what was similar in participant responses and program definitions | |

| Humor | |

| Giving the turn to the next pair | |

| Hedging | |

| Compare and contrast | |

| Moral reasoning | |

| Normalization | |

| “Mini-sermons” | |

| Self-talk | |

| Call-and-response |

A limitation of the qualitative study is that conclusions can only be drawn about what the facilitators did in this single activity. Previous to this activity, participants and facilitators had a history of five sessions together. The temporality of their relationship can get lost when only examining one time point (Peräkylä, 2004) and this history unquestionably influences the current activity. That noted, CA provided rich information about the implementation of SAAF the program. Through their empathy, shared laughter, and common experiences, it appears that, at least to some extent, facilitators did in fact share worldviews with participants as a result of cultural matching. Across situations, facilitators demonstrated reluctance to correct participants. Consequently, in some cases, participants were never exposed to the answer as defined by the curriculum. This finding may frustrate program designers if they expected participants to be able to use the terms “Integrationist” or “Separatist” in their everyday vocabulary. However, it is likely that participants came away from the program with the understanding that there are different ways to handle experiences with racism, which may be a more meaningful goal of the activity. Moreover, African American caregivers are inundated with messages from society that they are deficient in their ability to parent their children (Murry et al., 2004). Programs that reinforce these negative messages will certainly not be effective in engaging participants or providing the kind of support they need to feel efficacious in their caregiving. We cannot attempt to make definitive claims that certain strategies are culturally competent across all situations. As Silverman and Peräkylä (1990) affirm, there is no right or wrong way to respond to a participant because each interaction is locally devised. Simply put, understanding the rules guiding any interaction depend on a deep understanding of the context and its constituents. However, the strategies employed by facilitators to avoid negative evaluations (e.g. clarification, humor, giving the turn to the next group, reformulation of the participant’s response, compare and contrast, moral reasoning, mini-lectures, and self-talk, especially using call-and-response) appear to be culturally competent for this unique context by avoiding the negation of African American caregivers’ competence and thereby increasing caregivers’ engagement with the program (Murry et al., 2004). This engagement was especially visible as they came up with their own examples and ideas as a result of the facilitators’ adaptations.

Finally, this study produced implications for the design of programs and implementation assessments. In terms of the program, observations of this session served as a reminder to use simple, straightforward language when working with caregivers. In addition, facilitators appeared to have success with when they compared and contrasted the different perspectives. Having each team choose one situation and decide which of the three worldviews corresponded with the three responses depicted on the cards would likely help clarify this type of activity. The program has since been revised to simplify this activity. In terms of developing manuals, not everything can be scripted and to the extent that a program developer tries to over-script, the relationships between facilitators and participants and participant engagement with the material can be stifled. On the other hand, instructions or suggestions for how to handle pitfalls are very important. Some facilitators may have decided not to correct participants’ responses because it was not in the manual to do so. Fidelity can only be assessed in terms of what is scripted, which makes careful consideration of what to include all the more important. Finally, in terms of what “counts” as completing an action when assessing fidelity can be a challenging issue. For example, if the group is small, should it count against facilitators if they work with the whole group instead of dividing up into pairs (see the instructions in the manual in Figure 1, Number 2)? If participants (especially those who are elderly or have a disability) prefer to share their answers sitting down instead of standing by the appropriate poster (Number 3), does that really matter? What are the implications if the facilitator says the answer instead of the participant (Number 4)? If the group is large and some participants do not share their answers with the whole group, does that count as incomplete for Numbers 3 and 4? These are important questions that must be addressed in terms of the program theory with the developers of the program. It is also necessary to consider the purpose of the assessment, which could be for at least two reasons, to judge the skills of facilitator or to assess the content to which participants were exposed for analyses of program effects. The answers to questions about “what counts” depend highly on the purpose of the assessment.

In summary, the components of this mixed-method study complemented one another to provide a unique understanding of fidelity, attendance, and adaptation in the SAAF program. Although widely used, quantitative methods of assessing fidelity require a large degree of decision making as to the scope of the assessment. As each program is different, each fidelity measure is also different, limiting our ability to make comparisons across programs. However, results of the fidelity study were invaluable in supporting the underlying theory of the program, that is, exposure to material about how to assertively manage discrimination (i.e. through fidelity to the content and attendance during the session where the content was covered) increases caregivers’ use of racial socialization practices with their children. On the other hand, while CA proved to be a useful tool in examining how the facilitators adapted the program to assist participants in a difficult, yet theoretically important activity in the program, the method is extremely time consuming. It is necessary to choose a limited section of data when employing this type of in-depth analysis. This study represents a first step in the development of system for categorizing adaptations in a group-based parenting program for rural African American caregivers and illuminated adaptations made in a section of the session that was found to be difficult for participants and facilitators. Thus, the methods functioned together to provide an in-depth and unique picture of implementation in this important and underserved context.

Acknowledgments

Support for the Strong African American Families program was provided by grants from NIMH (RO1MH6304305) and NIAAA (RO1AA1276805). The first author’s time on the manuscript was partially supported by the University of Georgia Presidential Graduate Fellowship. This manuscript is based on a chapter from the first author’s doctoral dissertation. We also acknowledge support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) for this work through the Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology for Drug Abuse and Sex Risk Behavior, P30DA027828. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Biographies

Cady Berkel is a Faculty Research Associate at the Prevention Research Center at Arizona State University. She received a PhD in Child and Family Development from the University of Georgia in 2006. Her primary research interests relate to translational research to reduce health and social disparities. Specifically, her work focuses on importing evidence-based programs into real world settings and research that would enhance the cultural relevance of EBPs through the multidimensional study of implementation, with specific attention to cultural adaptations. She is also interested in basic research on the impact of discrimination on adolescent health and social disparities, and the protective influence of cultural factors. Cady Berkel is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: cady.berkel@asu.edu

Velma McBride Murry is an Endowed Chair, Education and Human Development, and Professor of Human and Organizational Development, Peabody College at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee. She received her PhD in Human Development and Family Relations, University of Missouri-Columbia, 1988. She has extensive expertise on adversity that includes race, ethnicity, and poverty; with a background in the role that parenting plays in addressing the needs of rural African American youth. She has completed an efficacy trial, the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program, designed to enhance parenting and family processes to in turn encourage youth to delay age at sexual onset and the initiation and escalation of alcohol and drug use. Currently, Dr Murry is implementing a randomized control trial of the Pathways for African American Success Program, a second generation version of the SAAF program, that is designed to test the feasibility and efficacy of delivering a family-based randomized prevention trial via computer-based interactive technology. This RCT aims to provide information about the potential of a computer-based versus a group-based intervention to increase the accessibility and diffusion potential of a HIV risk reduction programming for rural African Americans.

Kathryn J. Roulston is a Professor in the Qualitative Research Program in the Department of Lifelong Education, Administration, and Policy at the University of Georgia, where she teaches qualitative research methodology. Her research interests include qualitative research methods, qualitative interviewing, analyses of talk-in-interaction, and the preparation of qualitative researchers. She is author of Reflective interviewing: A Guide to Theory and Practice (2010), and has published articles and chapters on methodological issues in doing interview research and analyzing interview data.

Gene H. Brody is a Regent’s Professor at the Department of Child and Family Development, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia and Director of the Center for Family Research. His research focuses on the identification of family processes that contribute to academic and socioemotional competence in children and adolescents.

Contributor Information

Cady Berkel, Prevention Research Center, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, USA.

Velma McBride Murry, Center for Research on Rural Families and Communities, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Kathryn J. Roulston, Department of Lifelong Education, Administration, and Policy, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA

Gene H. Brody, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA

References

- Backer TE. Finding the Balance: Program Fidelity and Adaptation in Substance Abuse Prevention. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Ayers TS, Sandler IN. Untangling the effects of multiple dimensions of implementation in understanding the success of evidence-based programs. Presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN. Putting the pieces together: an integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science. 2011b;12(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely CH, Mayer JP, Gottschalk RG, Schmitt N, Davidson WS, Roitman DB, Emshoff JG. The fidelity-adaptation debate: implications for the implementation of public sector social programs. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15(3):253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Boatright SR, Bachtel DC, editors. The Georgia County Guide. The University of Georgia, Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development, University of Georgia Cooperative Extension, and Carl Vinson Institute of Government; Athens, GA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boruch RF, Gomez H. Sensitivity, bias and theory in impact evaluations. Professional Psychology. 1977;8(4):411–434. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Advancing prevention science and practice: challenges, critical issues, and future directions. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):69–72. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013984.83251.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research & Review. 2000;57(S1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, Mcnair L, Brown AC, Wills TA, Spoth RL, Luo Z, Chen Y-F, Neubaum-Carlan E. The strong African American families program: translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75(3):900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR. Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children who are Severely Emotionally Disturbed: Volume I. National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health, Georgetown University Child Development Center; Washington, DC: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dalaker J. Poverty in the United States, 2000. US Census Bureau Current Population Reports Series; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(1):23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew P, Heritage J. Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J, DuPre E. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury LA, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research. 2003;18(2):237–256. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury LA, Brannigan R, Hansen WB, Walsh J, Falco M. Quality of implementation: developing measures crucial to understanding the diffusion of preventive interventions. Health Education Research. 2005;20(3):308–313. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emshoff J, Blakely C, Gray D, Jakes S, Brounstein P, Coulter J, Gardner S. An ESID case study at the federal level. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32(3):345–357. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004753.88247.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haakana M. Laughter as a patient’s resource: dealing with delicate aspects of medical interaction. Text. 2001;21(1/2):187–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Graham JW, Wolkenstein BH, Rohrbach LA. Program integrity as a moderator of prevention program effectiveness: results for fifth-grade students in the adolescent alcohol prevention trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(6):568–579. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Bishop DC, Dusenbury L, Pankratz M, Albritton J, Albritton L, Strack J. Feeding information learned from adaptations back into program design. Presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Pankratz MM, Dusenbury L, Giles SM, Bishop DC, Albritton J, Albritton LP, Strack J. Styles of adaptation: the impact of frequency and valence of adaptation on preventing substance use. 2013 doi: 10.1108/09654281311329268. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath C, Hindmarsh J, Luff P. Video in Qualitative Research: Analysing Social Interaction in Everyday Life. Sage; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Helitzer D, Yoon S-J, Wallerstein N, Dow Y, Garcia-Velarde L. The role of process evaluation in the training of facilitators for an adolescent health education program. The Journal of School Health. 2000;70(4):141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]