Abstract

Conventional methods for intraoperative histopathologic diagnosis are labour- and time-intensive, and may delay decision-making during brain-tumour surgery. Stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy, a label-free optical process, has been shown to rapidly detect brain-tumour infiltration in fresh, unprocessed human tissues. Here, we demonstrate the first application of SRS microscopy in the operating room by using a portable fibre-laser-based microscope and unprocessed specimens from 101 neurosurgical patients. We also introduce an image-processing method – stimulated Raman histology (SRH) – which leverages SRS images to create virtual haematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slides, revealing essential diagnostic features. In a simulation of intraoperative pathologic consultation in 30 patients, we found a remarkable concordance of SRH and conventional histology for predicting diagnosis (Cohen's kappa, κ > 0.89), with accuracy exceeding 92%. We also built and validated a multilayer perceptron based on quantified SRH image attributes that predicts brain-tumour subtype with 90% accuracy. Our findings provide insight into how SRH can now be used to improve the surgical care of brain tumour patients.

The optimal surgical management of brain tumors varies widely depending on histologic subtype. Though some tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) have a distinct gross appearance, others are difficult to differentiate. Consequently, the importance of intraoperative histopathologic diagnosis in brain tumor surgery has been recognized for over 85 years1.

Existing intraoperative histologic techniques, including frozen sectioning and cytologic preparations, require skilled technicians and clinicians working in surgical pathology laboratories to produce and interpret slides2. However, the number of centers where brain tumor surgery is performed exceeds the number of board-certified neuropathologists, eliminating the possibility for expert intraoperative consultation in many cases. Even in the most advanced, well-staffed hospitals, turnaround time for intraoperative pathology reporting may delay clinical decision-making during surgery, highlighting the need for an improved system for intraoperative histopathology.

The ideal system for intraoperative histopathology would deliver rapid, standardized, and accurate diagnostic images to assist in surgical decision-making. Improved access to intraoperative histologic data would enable examination of clinically relevant histologic variations within a tumor and the assessment of the resection cavity for residual tumor. In addition, given that the percentage of tumor removed at the time of surgery is a major prognostic factor for brain tumor patients3, intraoperative techniques to accurately identify residual tumor are essential.

The development of stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy in 2008 created the possibility of rapid, label-free, high-resolution microscopic imaging of unprocessed tissue specimens4. While SRS has been shown to reveal key diagnostic histologic features in brain tumor specimens5-7, major technical hurdles have hindered its clinical translation. SRS microscopy requires two laser pulse trains that are temporally overlapped by less than the pulse duration (ie, <100fs) and spatially overlapped by less than the focal spot size (ie, <100nm). Achieving these conditions typically requires free-space optics mounted on optical tables and state-of-the-art, solid-state, continuously water-cooled lasers that are not suitable for use in a clinical environment4.

However, leveraging advances in fiber-laser technology8, we have engineered a clinical SRS microscope, allowing us to execute SRS microscopy in a patient care setting. Light guiding by the optical core of the fiber and the unique polarization-maintaining (PM) implementation of the laser source have enabled service-free operation in our operating room for over a year. The system also includes improved noise cancellation electronics for the suppression of high relative intensity noise, one of the major challenges of executing fiber-laser-based SRS microscopy.

Using this system, we show that SRS microscopy can serve as an effective, streamlined alternative to traditional histologic methods, eliminating the need to transfer specimens out of the operating room to a pathology laboratory for sectioning, mounting, dyeing, and interpretation. Moreover, because tissue preparation for SRS microscopy is minimal, key tissue architectural details commonly lost in smear preparations and cytologic features often obscured in frozen sections are preserved. We also report a unique method for SRS image processing that simulates hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, called stimulated Raman histology (SRH), which highlights key histoarchitectural features of brain tumors and enables diagnosis in near-perfect agreement with conventional H&E-based techniques. Finally, we demonstrate how a supervised machine learning approach, based on quantified SRH image attributes, effectively differentiates among diagnostic classes of brain tumors. Our study demonstrates that SRH may provide an automated, standardized method for intraoperative histopathology that can be leveraged to improve the surgical care of brain tumors in the future.

Engineering a Clinical SRS Microscope

To eliminate reliance on optical hardware incompatible with the execution of SRS microscopy in an operating room, we created a fully-integrated imaging system with 5 major components: 1) a fiber-coupled microscope with a motorized stage; 2) a dual-wavelength fiber-laser module; 3) a laser control module; 4) a microscope control module; and 5) a computer for image acquisition, display, and processing. The entire system is mounted in a portable, self-contained clinical cart, utilizes a standard wall plug, and does not require water-cooling (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Engineering a clinical SRS microscope.

(A) SRS microscope in the UMHS operating room. (B) Key components of the dual-wavelength fiber-laser-coupled microscope required to create a portable, clinically compatible SRS imaging system. The top arm of the laser diagram indicates the scheme for generating the Stokes beam (red), while the bottom arm generates the pump beam (orange). Both beams are combined (purple) and passed through the specimen. (C) Raw 2845cm−1 image of human tissue before, and (D) after balanced-detection-based noise cancellation. HNLF = highly non-linear fiber; PPLN = periodically poled lithium niobate; PD = photo diode.

The dual-wavelength fiber-laser is based on the fact that the difference frequency of the two major fiber gain media, Erbium (Er) and Ytterbium (Yb), overlaps with the high wavenumber region of Raman spectra. As previously described8, the two synchronized narrow-band laser pulse-trains required for SRS imaging are generated by narrow-band filtering of a broad-band super-continuum derived from a single fiber-oscillator and, subsequently, amplification in the respective gain media (Fig. 1B).

For clinical implementation, we developed an all-fiber system based on PM components, which greatly improved stability over the previous non-PM system. The system described here was stable throughout transcontinental shipping (from California to Michigan), and continuous, service-free, long-term (>1 year) operation in a clinical environment, without the need for realignment. To enable high-speed diagnostic-quality imaging (1Mpixel in 2sec per wavelength) with a signal-to-noise ratio comparable to what can be achieved with solid-state lasers, we scaled the laser output power to approximately 120mW for the fixed wavelength 790nm pump beam and approximately 150mW for the tunable Stokes beam over the entire tuning range from 1010nm to 1040nm at 40MHz repetition rate and 2 picosecond transform-limited pulse duration. We also developed fully custom laser controller electronics to tightly control the many settings of this multi-stage laser system based on a micro-controller. Once assembled, we determined that the SRS microscope had a lateral resolution of 360nm (full width of half maximum) and axial resolution of 1.8μm (Fig. S1).

While development of an all-fiber system was necessary for clinical implementation of SRS, relative intensity noise intrinsic to fiber lasers vastly degrades SRS image quality (Fig. 1C). To improve image quality, we developed a noise-cancelation scheme based on auto-balanced detection8, in which a portion of the laser beam is sampled to provide a measure of the laser noise that can then be subtracted in real-time. Here we demonstrate that we can achieve ~25x improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio in a clinical setting, without the need for adjustment, which is essential for revealing microscopic tissue architecture (Fig. 1D).

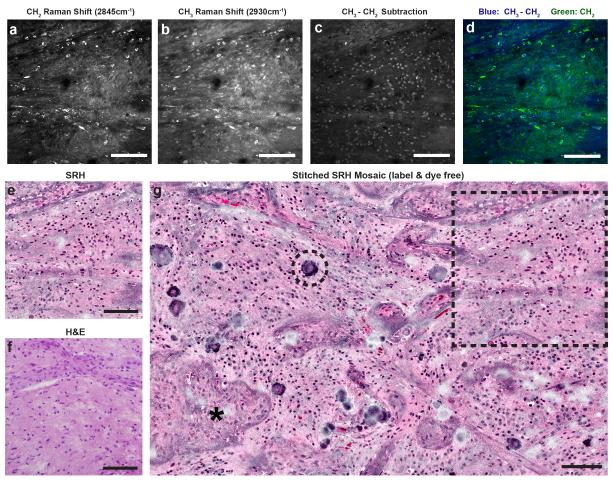

Processing of Clinical SRS Images

Histologic images of fresh, unstained surgical specimens are created with the clinical SRS microscope by mapping two Raman shifts: 2845cm−1, which corresponds to CH2 bonds that are abundant in lipids (Fig. 2A), and 2930cm−1, which corresponds to CH3 bonds that predominate in proteins and DNA (Fig. 2B). Assigning a subtracted CH3-CH2 image (Fig. 2C) to a blue channel and assigning the CH2 image to the green channel results in an image with contrast that is suitable for brain tumor detection (Fig. 2D)9. However, given the ultimate goal of creating an imaging system that produces histologic images that are familiar to clinicians10-12, we devised SRH, a method of processing SRS images that is reminiscent of H&E staining (Fig. 2E). Unlike previous methods for achieving virtual H&E images through hyperspectral SRS microscopy12, SRH relies on only two Raman shifts (2845cm−1 and 2930cm−1) to generate the necessary contrast. Though the colors in SRH images do not correspond exactly with the staining of acidic (hematoxylin) or basic (eosin) moieties, there is strong overlap between the two methods (Fig. 2F), simplifying interpretation. To produce SRH images, fields-of-view (FOVs) are acquired at a speed of 2 sec per frame in a mosaic pattern, stitched, and recolored. The end result is an SRH mosaic (Fig. 2G) resembling a traditional H&E-stained slide. The time of acquisition for the mosaic shown in Figure 2G is 2.5 min and it can be rapidly transmitted to any networked workstation directly from an operating room.

Fig. 2. Creating virtual H&E slides with the clinical SRS microscope.

(A) CH2 and (B) CH3 images are acquired and (C) subtracted. (D) The CH2 image is assigned to the green channel, and CH3-CH2 image is assigned to the blue channel to create a two-color blue-green image. Applying an H&E lookup table, SRH images (E) are comparable to a similar section of tumor (F) imaged after formalin-fixation, paraffin-embedding (FFPE), and H&E staining. (G) Mosaic tiled image of several SRH FOVs to create a mosaic of imaged tissue. Asterisk (*) indicates a focus of microvascular proliferation, dashed circle indicates calcification, and the dashed box demonstrates how the FOV in (E) fits into the larger mosaic. Scale bars = 100μm.

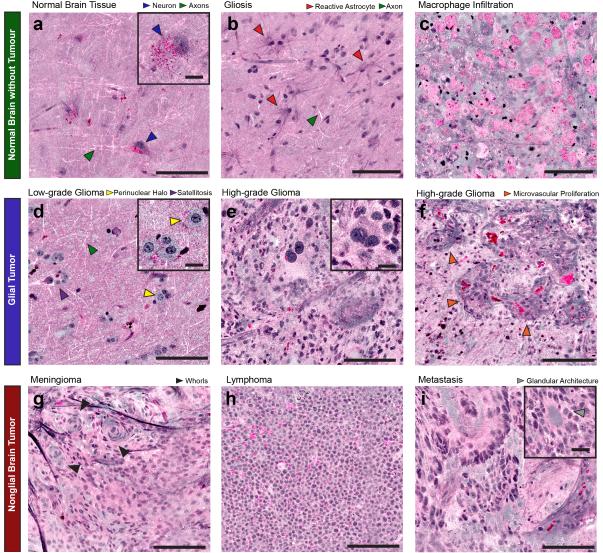

Detection of Diagnostic Histologic Features with SRH

We assessed the ability of SRH to reveal the diagnostic features required to detect and classify tumors of the CNS by imaging fresh surgical specimens from 101 neurosurgical patients (Table S1) via an institutional review board (IRB)-approved protocol (UM IRB HUM00083059). Like conventional H&E images, SRH images reveal the cellular and architectural features that permit differentiation of non-lesional (Fig. 3A-C) and lesional (Fig. 3D-I) and tissues. When imaged with SRH, architecturally normal brain tissue from anterior temporal lobectomy patients (patients 6, 11, and 93) demonstrates neurons with angular cell bodies containing lipofuscin granules (Fig. 3A), and lipid-rich axons that appear as white linear structures (Fig. 3A-B). Non-neoplastic reactive changes including gliosis (Fig. 3B) and macrophage infiltration (Fig. 3C) that may complicate intraoperative diagnosis are also readily visualized with SRH. Key differences in cellularity, vascular pattern, and nuclear architecture that distinguish low-grade (Fig. 3D; patient 3) from high-grade (Fig. 3E-F; patient 21) gliomas are apparent as well. Notably, SRH suggests that the perinuclear halos of oligodendroglioma cells (Fig. 3D), not typically seen on frozen section and thought to be an artifact of fixation13, are reflective of abundant protein-rich tumor cell cytoplasm. In addition, by highlighting the protein-rich basement membrane of blood vessels, SRH is well-suited for highlighting microvascular proliferation in high-grade glioma (Fig. 3F; patient 37).

Fig. 3. Imaging of key diagnostic histoarchitectural features with SRH.

(A) Normal cortex reveals scattered pyramidal neurons (blue arrowheads) with angulated boundaries and lipofuscin granules, which appear red. White linear structures are axons (green arrowheads). (B) Gliotic tissue contains reactive astrocytes with radially directed fine protein-rich processes (red arrowheads) and axons (green arrowheads). (C) A macrophage infiltrate near the edge of a glioblastoma reveals round, swollen cells with lipid-rich phagosomes. (D) SRH reveals scattered “fried-egg” tumor cells with round nuclei, ample cytoplasm, perinuclear halos (yellow arrowheads), and neuronal satellitosis (purple arrowhead) in a diffuse 1p19q-co-deleted low-grade oligodendroglioma. Axons (green arrowhead) are apparent in this tumor-infiltrated cortex as well. (E) SRH demonstrates hypercellularity, anaplasia, and cellular and nuclear pleomorphism in a glioblastoma. A large binucleated tumor cell is shown (inset) in contrast to smaller adjacent tumor cells. (F) SRH of another glioblastoma reveals microvascular proliferation (orange arrowheads) with protein-rich basement membranes of angiogenic vasculature appearing purple. SRH reveals (G) the whorled architecture of meningioma (black arrowheads), (H) monomorphic cells of lymphoma with high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, and (I) the glandular architecture (inset; gray arrowhead) of a metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Large image scale bars = 100μm; inset image scale bars =20μm.

SRH also reveals the histoarchitectural features that enable diagnosis of tumors of non-glial origin (Fig. 3G-I), including the whorled architecture of meningiomas (Fig. 3G; patient 26), the discohesive monomorphic cells of lymphoma (Fig. 3H; patient 31), and the glandular architecture, large epithelioid cells, and sharp borders of metastatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3I; patient 57). SRH is also capable of visualizing morphologic features that are essential in differentiating the three most common pediatric posterior fossa tumors–juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma, medulloblastoma, and ependymoma–each of which have divergent goals for surgical management14. In pilocytic astrocytomas, SRH detects piloid (hair-like) architecture and Rosenthal fibers, which appear dark on SRH due to their high protein content (Fig. S2A; patient 98). SRH also reveals the markedly hypercellular, small, round, blue cell appearance and rosettes in medulloblastoma (Fig. S2B; patient 101), as well as the monomorphic round-to-oval cells forming perivascular pseudorosettes in ependymoma (Fig. S2C; patient 87).

Detection of Intratumoral Heterogeneity with SRH

Gliomas often harbor histologic heterogeneity, which complicates diagnosis and treatment selection. Heterogeneity is particularly common in low-grade gliomas suspected of having undergone malignant progression, and demonstration of anaplastic transformation is essential for making a diagnosis. SRH was successful in detecting heterogeneity of tumor grade within a specimen collected from a patient with a recurrent oligodendroglioma of the right frontal cortex. In that specimen, SRH revealed both low-grade architecture and areas of high-grade architecture characterized by hypercellular, anaplastic, and mitotically active tumor (Fig. 4A, patient 41).

Fig. 4. SRH reveals structural heterogeneity in human brain tumors.

(a) An MRI of a patient with a history of low-grade oligodendroglioma who was followed for an enlarging enhancing mass (yellow arrowhead) in the previous resection cavity (red circle). SRH imaging of the resected tissue reveals areas with low-grade oligodendroglioma architecture in some regions (left column) with foci of anaplasia (right column) in other areas of the same specimen. (b) Gangliogliomas are typically composed of cells of neuronal and glial lineage. SRH reveals architectural differences between a shallow tissue biopsy at the location indicated with a green arrowhead on the preoperative MRI where disorganized binucleated dysplastic neurons predominate (left), and a deeper biopsy (blue arrowhead) where architecture is more consistent with a hypercellular glioma (right). FFPE H&E images are shown for comparison.

In other tumors, such as mixed glioneuronal tumors, histologic heterogeneity is a necessary criterion for diagnosis: while any single histopathologic sample may reveal glial or neuronal architecture, the identification of both is necessary for diagnosis. In a patient with suspected ganglioglioma, a glioneuronal tumor, intraoperative SRH images of a superficial specimen (Fig 4B; patient 96) revealed clustered dysplastic neurons, while a deep specimen revealed hypercellular piloid glial architecture. Consequently, by providing a rapid means of imaging multiple specimens, SRH reveals intratumoral heterogeneity needed to establish clinically relevant variations in both grade and histoarchitecture during surgery.

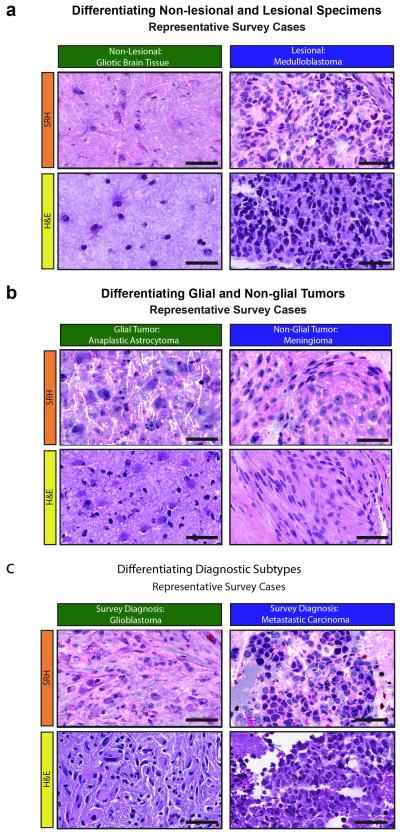

Quantitative Evaluation of SRH-Based Diagnosis

Given its ability to reveal diagnostic histologic features, we hypothesized that SRH could provide an alternative to existing methods of intraoperative diagnosis. To test this hypothesis, we imaged specimens from 30 neurosurgical patients where intraoperative diagnosis was rendered using routine frozen sectioning or cytological techniques (Table S1, patients 72-101). Adjacent portions of the same specimens were utilized for both routine histology and SRH.

To simulate the practice of intraoperative histologic diagnosis, a computer-based survey was created, in which three board-certified neuropathologists (K.A.M., S.R., M.S.), each practicing at different institutions, were presented with SRH or routine (smear and/or frozen) images, along with a brief clinical history regarding the patient’s age group (child/adult), lesion location, and relevant past medical history. The neuropathologists responded with an intraoperative diagnosis for each case the way they would in their own clinical practices. Responses were graded based on: 1) whether tissue was classified as lesional or non-lesional, 2) for lesional tissues, whether they had a glial or non-glial origin, and 3) whether the response contained the same amount of diagnostic information (lesional status, grade, histologic subtype) as the official clinical intraoperative diagnosis.

Assessing the pathologists’ diagnostic performance when utilizing SRH versus clinical frozen sections revealed near-perfect concordance (Cohen’s kappa) between the two histological methods for distinguishing lesional and non-lesional tissues (κ=0.84-1.00) (Table 1) and for distinguishing lesions of glial origin from non-glial origin (κ=0.93-1.00) (Table 1). There was also near-perfect concordance between the two modalities in predicting the final diagnosis (κ=0.89-0.92) (Table 1). Inter-rater reliability among reviewers and concordance between SRH and standard H&E-based techniques for predicting diagnosis was also nearly perfect (κ=0.89-0.92). Notably, with SRH, the pathologists were highly accurate in distinguishing lesional from non-lesional tissues (98%), glial from non-glial tumors (100%), and predicting diagnosis (92.2%). These findings suggest that pathologists’ ability to derive histopathologic diagnoses from SRH images is both accurate and highly concordant with traditional histological methods.

Table 1.

SRH vs Conventional Histology Survey Results

| Specimen Type | Imaging Modality | NP1 | NP2 | NP3 | Combined Accuracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | |||

| Differentiating Non-lesional and Lesional Specimens | ||||||||

| Normal | SRH | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 93% |

| H&E | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 86% | |

| Glial Tumor | SRH | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 100% |

| H&E | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 100% | |

| Non-Glial Tumor | SRH | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 100% |

| H&E | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 100% | |

| Total | SRH | 29 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 98% |

| H&E | 28 | 2 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 97.7% | |

| Combined accuracy | 90% | 100% | 100% | 95% | ||||

| Concordance (k) | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Differentiating Glial and Non-glial Tumors | ||||||||

| Glial Tumor | SRH | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 100% |

| H&E | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 100% | |

| Non-Glial Tumor | SRH | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 100% |

| H&E | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 100% | |

| Total | SRH | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 100% |

| H&E | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 100% | |

| Combined accuracy | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||

| Concordance (k) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Differentiating Diagnostic Subtypes | ||||||||

| Normal | SRH | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 93% |

| H&E | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 86% | |

| Glial Tumor | SRH | 14 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 86.6% |

| H&E | 14 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 95.5% | |

| Non-Glial Tumor | SRH | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 100% |

| H&E | 10 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 96.6% | |

| Total | SRH | 28 | 1 | 27 | 3 | 28 | 2 | 92.2% |

| H&E | 27 | 3 | 28 | 2 | 30 | 0 | 94.4% | |

| Combined accuracy | 91.6% | 91.6% | 97% | 94% | ||||

| Concordance (k) | 0.924 | 0.855 | 0.923 | |||||

While both methods were highly accurate in predicting diagnosis, six of the SRH-based diagnostic discrepancies occurred in the classification of glial tumors (Table 1, Fig. 5C and Fig. S3A). In three separate instances, pathologists were able to correctly identify a specimen as being glioma, but did not provide a specific grade. Two specimens classified as “Glioma” with SRH were classified as “High-Grade Glioma” with H&E based techniques. High-grade features in gliomas include: significant nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation and necrosis. Assessment of nuclear atypia and mitotic figures is subjective and requires ample expertise based on review of hundreds of cases to set up a threshold of “normal” vs atypical morphology in a specimen. Given the subtle difference in appearance of nuclear architecture in H&E and SRH, pathologists may have been more conservative in terms of rendering atypical and mitotic attributions to tumor cells with SRH.

Fig. 5. Simulation of intraoperative histologic diagnosis with SRH.

A web-based survey consisting of specimens from 30 patients (patients 72-101) imaged with both SRH and conventional H&E methods was administered to three neuropathologists. Neuropathologists recorded free-form responses as they would during a clinical intraoperative histologic consult. Responses were graded based on whether tissue was judged as (A) lesional or non-lesional, (B) glial or non-glial, and (C) on the accuracy of diagnosis. SRH and H&E preparations for six examples of portions of specimens presented in the survey are shown: gliotic brain tissue (patient 91), medulloblastoma (patient 101), anaplastic astrocytoma (patient 76), meningioma (patient 95), glioblastoma (patient 82), and metastatic carcinoma (patient 74). Scale bars = 50μm.

Differences in tissue preparation between conventional techniques (i.e., sectioning) and SRH (i.e., gentle squash) result in differences in the appearance of vascular architecture. Microvascular proliferation is defined as intraluminal endothelial proliferation (several layers of endothelial cells in a given vessel) and is essential in grading gliomas at the time of intraoperative consultation. This can be easier to observe when tissue is sectioned and analyzed in two dimensions (Fig. S3B). In contrast, while SRH is able to highlight basement membranes nicely, in some cases, it does not reveal the classic architectural features of microvascular proliferation (Fig. S3C).

Undersampling from specimens may have also contributed to the discrepancies observed. In three survey items, pathologists misdiagnosed ependymoma as “pilocytic astrocytoma” or gave a more general description of the tumor as “low-grade glioma” using SRH images (Fig. S3A). Ependymomas and pilocytic astrocytomas may have similar nuclear morphology of monotonous elongated nuclei embedded in a background composed of of thin glial processes (piloid-like). In the absence of obvious perivascular pseudorosettes, ependymal rosettes or hyalinized vessels, which were not obvious in the survey items, and may be unevenly distributed throughout a tumor, it is understandable that an ependymoma could be misclassified as a pilocytic astrocytoma. Given the concordance of SRH-images with traditional H&E images in our patients, we hypothesize that these errors might have been avoided if larger specimens were provided to reviewers.

Machine Learning-Based Tissue Diagnosis

Intraoperative image data that is most useful for clinical decision-making is that which is rapidly obtained and accurate. Interpretation of histopathologic images by pathologists is labor- and time-intensive and prone to inter-observer variability. Consequently, a system rapidly delivering prompt, consistent, and accurate tissue diagnoses would be greatly helpful during brain tumor surgery. While we have previously shown that tumor infiltration can be predicted by quantitative SRS images through automated analysis of tissue attributes6, we hypothesized that more robust computational processing would be required to predict tumor diagnostic class.

We employed a machine learning process called a multilayer perceptron (MLP) for diagnostic prediction because it is 1) easy to iterate, 2) easy to verify, and 3) efficient with current computational power. To create the MLP, we incorporated 12,879 400×400μm SRH FOVs from our series of 101 patients. We used WND-CHRM, an open-source image classification program that calculates 2,919 image attributes for machine learning15 to assign quantified attributes to each FOV. Normalized quantified image attributes were fed into the MLP for training, iterating until the difference between the predicted and observed diagnoses was minimized (see Methods section).

To test the accuracy of the MLP, we used a leave-one-out approach, wherein the training set contained all FOVs except those from the patient being tested. This method maximizes the size of the training set and eliminates possible correlation between samples in the training and test sets. The MLP makes predictions on an individual FOV level, yielding probabilities that a given FOV belongs to one of the four diagnostic classes: non-lesional, low-grade glial, high-grade glial, or non-glial tumor (including metastases, meningioma, lymphoma, and medulloblastoma) (Fig. 6A). The four diagnostic classes were selected because they provide critical information for informing decision-making during brain tumor surgery.

Fig. 6. MLP classification of SRH images.

The specimen from patient 87, a low-grade ependymoma, was classified by the MLP as a low-grade glial tumor. (A) An SRH mosaic depicting the low-grade glial tumor diagnostic class with individual FOVs designated by dashed lines (center). Four individual FOVs are depicted at higher scale, with the MLP diagnostic probability for all four categories listed above: P(NL) = probability of non-lesional; P(LGG) = probability of low-grade glial; P(HGG) = probability of high-grade glial; P(NG) = probability of non-glial. Representative FOVs include a FOV with a small number of ovoid tumor cells (arrowhead) classified as low-grade glioma (top left, orange outline), a FOV with high cellularity with frequent hyalinized blood vessels (arrowheads) classified as non-glial tumor (top right, green outline), a FOV with moderate cellularity and abundant piloid processes (bottom right, yellow outline) classified as a low-grade glioma, and a FOV with higher cellularity and several prominent vessels (arrowheads) classified as high-grade glial tumor (bottom left, blue outline). Scale bars are 100μm for the individual FOVs and 500μm for the mosiac image. (B) Probability heatmaps overlaid on the SRH mosaic image indicate the MLP-determined probability of class membership for each FOV across the mosaic image for the four diagnostic categories. Colored boxes correspond to the FOVs highlighted in A.

Given the histoarchitectural heterogeneity of CNS tumors and the fact that some specimens may contain a mixture of normal and lesional FOVs, we judged the diagnostic accuracy of the MLP based on the most common or modal-predicted diagnostic class of FOVs within each specimen (Fig. 6B). For example, while the specimen from patient 87 exhibited some features of all diagnostic classes in various SRH FOVs (Fig. 6A), the MLP assigned the low-grade glial category as the highest probability diagnosis in a preponderance of the FOVs (Fig. 6B), resulting in the correct classification of this specimen as a low-grade glial tumor.

To evaluate the MLP in a test set of cases read by multiple pathologists, we applied the leave-one-out approach on each of the 30 cases included in the survey administered to pathologists, as described above. Based on modal diagnosis, the MLP accurately differentiated lesional from non-lesional specimens with 100% accuracy (Fig. 7A). Additionally, the diagnostic capacity of the MLP for classifying individual FOVs as lesional or non-lesional was excellent, with 94.1% specificity and 94.5% sensitivity (AUC=0.984 [Fig. S4]). Among lesional specimens, the MLP differentiated glial from non-glial specimens with 90% accuracy at the sample level (Fig. 7B). The modal diagnostic class predicted by the MLP was 90% accurate in predicting the diagnostic class rendered by pathologists in the setting of our survey (Fig. 7C).

Fig 7. MLP-based diagnostic prediction.

(A) Heat map depiction of the classification of cases as lesional or non-lesional via MLP. Green checks indicate correct MLP prediction, red circles indicate incorrect prediction. (B) Heat map depiction of the classification of cases as glial or non-glial via MLP. Green checks indicate correct MLP prediction, red circles indicate incorrect prediction. (C) Summary of MLP results from test set of 30 neurosurgical cases (patients 72-101). The fraction of correct tiles is indicated by the hue and intensity of each heat map tile, as well as the predicted diagnostic class.

The cases misclassified by the MLP included a minimally hypercellular specimen with few Rosenthal fibers from a pilocytic astrocytoma (patient 84) classified as non-lesional, rather than low-grade glioma. In this specimen, many of the FOVs resemble normal glial tissue (Fig. S5A). Another misclassified specimen from a patient with leptomeningeal metastatic carcinoma (patient 72) contained only 2 FOVs containing tumor (Fig. S5B). The glioblastoma specimen from patient 82 (Fig. S5C), misclassified as a non-glial tumor by the MLP, contained protein-rich structural elements that resembled the histoarchitecture of metastatic tumors imaged with SRH (Fig. S5D, patient 85). Despite these errors, the accuracy and overall ability of the MLP in automated detection of lesional status and diagnostic category provides proof-of-principle for how the MLP could be used for automated diagnostic predictions.

DISCUSSION

Accurate intraoperative tissue diagnosis is essential during brain tumor surgery. Surgeons and pathologists rely on trusted techniques such as frozen sectioning and smear preparations that are reliable but prone to artifacts that limit interpretation and may delay surgery. A simplified standardized method for intraoperative histology would create the opportunity to use intraoperative histology to ensure more efficient, comprehensive sampling of tissue within and surrounding a tumor. By ensuring high quality tissue is sampled during surgery, SRH raises the yield on testing biopsies for molecular markers (e.g. IDH and ATRX mutation, 1p19q co-deletion, MGMT and TERT-promoter alteration) that are increasingly important in rendering final diagnosis. In this manuscript, we report the first demonstration of SRS microscopy in a clinical setting and show how it can be used to rapidly create histologic images from fresh specimens with diagnostic value comparable to conventional techniques.

Fluorescence-guided surgery16, mass spectrometry17, Raman spectroscopy18, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy19,20, and optical coherence21 tomography, which exploit histologic and biochemical differences between tumor-infiltrated and normal tissues, have been proposed as methods for guiding excision of brain and other types of tumors22,23. To date, however, no microscopic imaging modality tested in a clinical setting has been successful in rapidly creating diagnostic-quality images to inform intraoperative decision-making. Here we show that by leveraging advances in optics and fiber-laser engineering, it is possible to create an SRS microscope that is easy to operate, durable, and compatible with a patient care environment, which rapidly provides diagnostic histopathologic images.

SRH is well-suited for integration into the existing workflow for brain tumor surgery. A surgical instrument that can simultaneously collect biopsies for SRH and be tracked by a stereotactic navigational system would enable the linkage of histologic and positional information in a single display, as previously suggested24. Integration of SRH and surgical navigation would create the possibility of verifying that maximal safe cytoreduction has been executed throughout a surgical cavity. In situations where tumor is detected by SRH but cannot be safely removed, it might be possible to serve as a way to better focus the delivery of adjuvant therapies.

As medical data become increasingly computer-based, the opportunity to acquire virtual histologic sections via SRS microscopy creates numerous opportunities. For example, in many clinical settings where brain tumor surgery is carried out, neuropathology services are not available. Currently there are 785 board-certified neuropathologists serving the approximately 1,400 hospitals performing brain tumor surgery in the United States (Table S2). A networked SRS microscope, like the prototype introduced here, streamlines both sample preparation and imaging and creates the possibility of connecting expert neuropathologists to surgeons–either within the same hospital or in another part of the world–to deliver precise intraoperative diagnosis during surgery.

Computer-aided diagnosis may ultimately reduce the inter-reader variability inherent in pathologic diagnosis and might provide guidance in settings where an expert neuropathologist is not available. Our results and the work of others suggest that machine learning algorithms can be used to detect and diagnose brain tumors. Prior work in computer-aided diagnosis in neuropathology has shown promise in differentiating diagnostic entities in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, H&E-stained whole slide images25,26. The ideal computer-aided diagnostic system for intraoperative histology would reliably predict diagnosis in small fresh tissue samples. The classifier reported here is capable of distinguishing lesional from non-lesional tissue samples and in predicting diagnostic class based on pooled tile data. In the future, we anticipate that a machine learning approach will be capable of finer diagnostic classification. We also hypothesize that the accuracy of diagnostic classifiers might also be improved via 1) exploring alternative neural network configurations and systems for convolution; 2) employing feature-based classification; 3) utilizing support vector machines or statistical modeling approaches; and 4) applying rules for data interpretation that account for demographic factors and medical history.

OUTLOOK

SRS microscopy can now be utilized to provide rapid intraoperative assessment of tissue architecture in a clinical setting with minimal disruption to the surgical workflow. SRH images may ultimately be used to render diagnosis in brain tumor specimens with a high degree of accuracy and near-perfect concordance with standard intraoperative histologic techniques. Prospective, randomized clinical studies will be necessary to validate these results and define how SRH can be used to expedite clinical decision-making and improve the care of brain tumor patients.

METHODS

Study Design

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1) males and females; 2) subjects undergoing brain tumor resection at the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS); 3) subjects (or designee) able to provide informed consent; and 4) subjects in which there was excess tumor tissue beyond what was needed for routine diagnosis. The sample size was estimated at 100 patients to ensure adequate representation of all major tumor types for analysis and based on the design of prior studies comparing SRS and H&E. The central goals of this study were: 1) to build and verify the first clinical SRS microscope; 2) to judge SRH as a means of providing diagnostic histopathologic images; 3) to determine if machine learning could accurately classify SRH images fresh human brain tumor specimens. We began by collecting biopsies (N=125) from neurosurgical patients undergoing tumor resection (n=98) or anterior temporal lobectomy (n=3). Each specimen was imaged immediately after removal with SRS microscopy. A trained neuropathologist (S.C.P) then classified each biopsy based on WHO diagnostic criteria13. We then quantified the correlation between SRH and H&E tissue imaging through a survey administered to neuropathologists (S.R., M.S., K.M.). To quantify the SRH images, we utilized WND-CHRM, which assigns 2,919 attributes to each image. We then used the quantified image attributes to build and train an MLP to classify the images based on diagnostic class. Diagnostic predictions were rendered based on the diagnostic class predicted most commonly by the MLP for FOVs in a given specimen.

Tissue Collection and Imaging

All tissues were collected in the context of a University of Michigan Medical School IRB-approved protocol from patients who provided informed consent (HUM0000083059). Tissues in excess of what was needed for diagnosis were eligible for imaging. In a subset of patients where the frozen section was large enough to split (patients 72-101), half of the specimen was routed for SRH imaging, while half of the specimen became the tissue for clinical frozen section diagnosis.

To image tissue with the clinical SRS microscope, a small (approximately 3mm thick) portion of fresh tissue was placed on a standard uncoated glass slide in the center of a small piece of two-sided tape and flattened to a thickness of 120μm in a manner similar to a standard squash preparation. Normal saline (50μL) was applied to the tissue and a coverslip was applied to the tissue and adhered to the slide, creating a chamber for imaging. This slide was then placed on a motorized stage and focused using standard transmission light microscopy. Using custom scripts in μ-Manager software and ImageJ software, two-channel (2845cm−1 and 2930cm−1) images were obtained in a mosaic fashion.

Our prototype system is built on an Olympus microscope body, and we developed a fully custom beam-scanning unit that seamlessly integrates the laser source through fiber delivery. We also developed control electronics for both the laser and the microscope. Our custom imaging software is based on the open-source microscopy platform μ-Manager. The imaging system appears as a “camera,” allowing us to leverage all the automated microscopy features provided by the μ-Manager environment to enable multi-color mosaic imaging.

Virtual H&E Coloring

Generating a virtual H&E image from the 2845cm−1 and 2930cm−1 images acquired from the SRS microscope utilizes a simple linear color-mapping of each channel. After channel subtraction and flattening (described in the following section), a linear color remapping is applied to both the 2845cm−1 and the 2930cm−1 channel. The 2845cm−1 image, a grayscale image, is linearly mapped such that a strong signal in the 2930cm−1 image maps to an eosin-like reddish-pink color instead of white. A similar linear mapping is applied to the 2930cm−1 image with a hematoxylin-like dark-blue/violet color mapped to a strong signal. Finally, these two layers are linearly added together to result in the final virtual-colored H&E image.

The exact colors for the H&E conversion were selected by a linear optimization based on a collection of true H&E-stained slides created by the UMHS Department of Pathology. An initial seed color was chosen at random for both H&E conversions. The previously described linear color-mapping and addition process was completed with these initial seed colors. The ensuing image was hand-segregated into a cytoplasmic and nuclear portion. These portions were compared with the true H&E images and a cytoplasmic and nuclear hue difference between generated false-colored H&E and true H&E was elucidated. The H&E seed colors were modified by these respective hue differences and the process was repeated until the difference between generated and true images was less than 1% different by hue.

Image Acquisition and Stitching

The procedure for generating a virtual-colored H&E image from the SRS microscope consists of 6 discrete steps:

A mosaic acquisition script is started on the control computer that acquires an (NxN) series of 1024×1024 pixel images from a pre-loaded tissue sample. These images are acquired at the 2845cm−1 and 2930cm−1 Raman shifts and saved as individual two-channel FOVs to a pre-specified folder.

The two-channel image is duplicated and a Gaussian blur is applied to the duplicated image. The original two-channel image is then divided by the Gaussian blur to remove artifacts of acquisition and tissue preparation.

The 2845cm−1 channel is subtracted from the 2930cm−1 channel in each FOV.

New FOVs are created with the 2845cm−1 channel and the 2930cm−1 minus 2845cm−1 channel.

The virtual-color H&E script (described in the above section) is run to create an H&E version of the subtracted and flattened tile.

The original tile is stitched as previously described27. The user is presented with an option to re-stitch with different stitching parameters if the initial stitch produces an unacceptable image. Upon successful stitching, a layout file is generated from the terminal positions of the individual tiles in the stitched image.

The virtual-color H&E images are stitched using the layout file generated in step #6, a significantly faster process than re-computing the stitching offsets and merges from scratch.

Survey Methodology

A computer-based survey consisting of 30 patients was developed and given to blinded neuropathologists (K.A.M, S.R., M.S.), who were presented with standard frozen H&E images and SRH images. All cases included in the survey were judged to have SRH and conventional H&E preparations that contained the essential architectural features required for diagnosis. Each image was accompanied by a short clinical history that included age group, sex, and presenting symptom(s). Survey responses were recorded automatically by the survey software. The intraoperative frozen and final pathologic diagnoses determined by standard clinical protocol employed by the UMHS Department of Pathology were also recorded. The survey responses were scored for accuracy on four levels: 1) for all specimens, whether tissue was lesional vs. non-lesional; 2) for lesional tissues, whether the origin was glial or non-glial; 3) for glial tumors, whether the tumor was low- or high-grade; and 4) for all tumors, the predicted diagnosis. Responses were considered concordant if accuracy scores were equal. The maximum possible score for each case was determined by the clinical frozen section diagnosis. For each case, the following diagnoses were used for statistical analysis: UMHS frozen section diagnosis, survey frozen section diagnosis, survey SRH diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

For each pathologist, we calculated Cohen’s kappa28 for SRH vs. H&E for lesion/no lesion and for glioma/no glioma. This provides information on how well SRH and H&E agree. Kappa was also calculated for final diagnosis from SRH vs. truth (clinical frozen section diagnosis) and for H&E vs. truth (clinical frozen section diagnosis), where final diagnosis was one of eleven categories, which tells us how well each pathologist was able to detect the truth from either SRH or H&E. Lastly, we calculated the three-reader inter-rater reliability (Fleiss’ kappa29) for SRH lesion/no lesion, SRH glioma/no glioma, H&E lesion/no lesion, and for H&E glioma/no glioma. R software was used for all statistical analyses.

No distributional assumptions are necessary for the kappa statistic. The only assumption is that the data are categorical and that SRH and H&E are measured on the same data, which they are. There is no estimate of variance for groups.

Generation of the MLP

The MLP was programmed with two software libraries: Theano and Keras. Theano (http://deeplearning.net/software/theano/index.html) is a high-performance low-level mathematical expression evaluator used to train the MLP. Keras (http://keras.io) is a high-level Python framework that serves as a wrapper for Theano, allowing rapid iteration and testing of different MLP configurations.

The MLP is designed as a fully-connected, 1,024-unit, 1 hidden layer, neural network. It comprises 8 sequential layers in the following order: 1) dense input layer with uniform initialization; 2) hyperbolic tangent activation layer; 3) dropout layer with dropout probability 0.2; 4) dense hidden layer with uniform initialization; 5) hyperbolic tangent activation layer; 6) dropout layer with dropout probability 0.2; 7) dense output layer with uniform initialization; and 8) a softmax activation layer corresponding to the number of classifications (Fig. S6).

Training of the MLP was performed using a training set that was exclusive from the survey test set. Loss was calculated using the multiclass log-loss strategy. The selected optimizer was the “Adam” optimizer. The optimizer’s parameters were as follows: learning rate= 0.001, beta_1=0.9, beta_2=0.999, and epsilon=1×10−8.

Image Processing and Analysis by the MLP

The process to convert a raw SRH image to a probability vector for each of the diagnoses is as follows:

Use FIJI to subtract the CH2 layer from the CH3 layer and flatten the image as described in the subsection “Tissue Collection and Imaging.”

Use FIJI to split the two-channel image into a separate CH2 layer and a CH3-CH2 layer.

For each of the previous tiles, create 4 duplications of the tile with 90-degree rotations (“rotamers”).

Use WNDCHRM (http://scfbm.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1751-0473-3-13) to generate signature files for each of the tiles from the previous step.

Normalize the signature files such that all of the feature values are uniformly and linearly mapped to the range (−1.0, 1.0).

(CH2). For each of the tiles that correspond to CH2-channel tiles, run the MLP as described above.

(CH2). Gather all of the rotamers for a given tile and average (arithmetic mean) the prediction values from them to create one consolidated diagnosis-probability vector for a given CH2-channel tile.

Repeat steps 6-7 for the CH3-CH2 channel.

For a given tile, compare the CH2-channel and the CH3-CH2 channel and discard the diagnosis-probability vector for the tile that has a lower maximal probability value.

For a case-by-case diagnosis, group all of the tiles for a case, remove any tile that doesn’t have a diagnosis probability of >0.25, and diagnose the case with the most prevalent (mode) diagnosis among the set of tiles.

MLP Evaluation with the Leave-One-Out Approach

To test the diagnostic accuracy of the MLP, we used a leave-one-out approach for the 30 patients that were used in the survey administered to neuropathologists. For each of the 30 patients used to evaluate the MLP, all FOVs (n) from that patient were placed in the test set. The training set was composed of the 12,879-n remaining FOVs. The 12,879 FOVs were screened by a neuropathologist to ensure they were representative of the diagnosis they were assigned to. FOVs were classified as non-lesional, pilocytic astrocytoma, ependymoma, oligodendroglioma, low-grade diffuse astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma, meningioma, lymphoma, metastatic tumor, and medulloblastoma.

The MLP was trained for 25 iterations, with the following 26 iteration weights recorded to use for validation of the test set. The test set was fed into each of these 26 weights with the resulting probabilities of each of the 12 diagnostic classes averaged to create a final probability for each diagnosis for each FOV. The 12 diagnoses were condensed to four classes (non-lesional, low-grade glial, high-grade glial, and non-glial) to achieve diagnostic predictions. The low-grade glial category included FOVs classified as pilocytic astrocytoma, ependymoma, oligodendroglioma, and low-grade diffuse astrocytoma. The high-grade glial category included FOVs classified as anaplastic oligodendroglioma, anaplastic astrocytoma, and glioblastoma. The non-glial category included FOVs classified as meningioma, lymphoma, metastatic tumor, and medulloblastoma.

Nationwide Inpatient Sample Query

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, was queried for years 2010 and 2011. The NIS for these years contains discharge data for all discharges from a sample of hospitals representing 20% of all nationwide discharges from nonfederal hospitals using a stratified random sampling technique.

Brain tumor resections or biopsies were identified using combinations of International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and treatment codes that were previously used for studies of adult tumors30, pediatric tumors31, and pituitary tumors32. Primary tumor ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure code codes used include 191.0-191.9, 225.0, 237.5, and 01.53, 01.59, 01.13, 01.14, respectively. Meningioma ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes used include 225.2, 192.1, 237.6, and 01.51, 01.13, and 01.14, respectively. Diagnosis code 198.3 and procedure codes 01.53, 01.59, 01.13, and 01.14 were used for metastases. Diagnosis code 225.1 and procedure code 04.01 was used for vestibular schwannomas. Diagnosis code 227.3 and procedure codes 07.62 and 07.65 were used for pituitary tumors.

The SRS microscopy system described in this publication is a prototype system that is intended for research use only. It does not comply with international safety standards nor has it received approval or clearance from any government agency such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Code availability

The computer code used to generate the results of this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, with the exception of proprietary portions of code used for the generation of the virtual H&E color scheme.

Data Availability

All raw and processed-image data generated in this work, including the representative images provided in the manuscript, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank H. Wagner for manuscript editing. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01EB017254 to X.S.X. and D.A.O.), National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (K08NS087118 to S.H.R.), the NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award Program T-R01 of the National Institutes of Health (R01EB010244-01 to X.S.X.), and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (P30CA046592). This work was also supported by Fast Forward Medical Innovation, the U-M Michigan Translational Research and Commercialization for Life Sciences Program (U-M MTRAC), the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (2UL1TR000433).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.A.O., B.P., Y.S.N., C.W.F., J.K.T., T.C.H., and S.C.P. conceived the study, designed the experiments, and wrote the paper, and were assisted by M.G. X.S.X. provided guidance on study design. D.A.O., S.L., and M.G. performed SRH imaging of all specimens. C.W.F. and J.K.T. built the SRS microscope. B.P., Y.S.N., J.B., and T.D.J. analyzed the data. S.C.P., K.A.M., S.H.R., M.S., S.V., A.P.L., and A. F.-H. interpreted microscopic images and revised the manuscript. T.D.J., D.A.W., and Y.S.N. performed statistical analyses. D.A.O, S.H.J, H.J.L.G., J.A.H., C.O.M., and O.S. provided surgical specimens for imaging. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

X.S.X. and D.A.O. are advisors and shareholders of Invenio Imaging, Inc., a company developing SRS microscopy systems. C.W.F. and J.K.T are employees and shareholders of the same company.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenhardt L, Cushing H. Diagnosis of Intracranial Tumors by Supravital Technique. Am J Pathol. 1930;6:541–552. 547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somerset HL, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Approach to the intraoperative consultation for neurosurgical specimens. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2011;18:446–449. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182169934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanai N, Polley M-Y, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. Journal of neurosurgery. 2011;115:3–8. doi: 10.3171/2011.2.JNS10998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freudiger CW, et al. Label-free biomedical imaging with high sensitivity by stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Science. 2008;322:1857–1861. doi: 10.1126/science.1165758. doi:322/5909/1857 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu FK, et al. Label-Free Neurosurgical Pathology with Stimulated Raman Imaging. Cancer Res. 2016 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji M, et al. Detection of human brain tumor infiltration with quantitative stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:309ra163. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji M, et al. Rapid, label-free detection of brain tumors with stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:201ra119. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freudiger CW, et al. Stimulated Raman Scattering Microscopy with a Robust Fibre Laser Source. Nat Photonics. 2014;8:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freudiger CW, et al. Multicolored stain-free histopathology with coherent Raman imaging. Lab Invest. 2012 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bini J, et al. Confocal mosaicing microscopy of human skin ex vivo: spectral analysis for digital staining to simulate histology-like appearance. Journal of biomedical optics. 2011;16:076008. doi: 10.1117/1.3596742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobbs J, et al. Confocal fluorescence microscopy for rapid evaluation of invasive tumor cellularity of inflammatory breast carcinoma core needle biopsies. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2015;149:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozeki Y, et al. High-speed molecular spectral imaging of tissue with stimulated Raman scattering. Nat Photon. 2012;6:845–851. doi: http://www.nature.com/nphoton/journal/v6/n12/abs/nphoton.2012.263.html-supplementary-information. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Classification of Tumours : WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th Edition World Health Organization (WHO); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson EM, et al. Prognostic value of medulloblastoma extent of resection after accounting for molecular subgroup: a retrospective integrated clinical and molecular analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00581-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlov N, et al. WND-CHARM: Multi-purpose image classification using compound image transforms. Pattern recognition letters. 2008;29:1684–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stummer W, et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2006;7:392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eberlin LS, et al. Classifying human brain tumors by lipid imaging with mass spectrometry. Cancer Research. 2012;72:645–654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jermyn M, et al. Intraoperative brain cancer detection with Raman spectroscopy in humans. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:274ra219. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2384. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camp CH, Jr, et al. High-Speed Coherent Raman Fingerprint Imaging of Biological Tissues. Nat Photonics. 2014;8:627–634. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2014.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans CL, et al. Chemically-selective imaging of brain structures with CARS microscopy. Opt Express. 2007;15:12076–12087. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kut C, et al. Detection of human brain cancer infiltration ex vivo and in vivo using quantitative optical coherence tomography. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:292ra100. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, et al. Differential diagnosis of breast cancer using quantitative, label-free and molecular vibrational imaging. Biomedical optics express. 2011;2:2160–2174. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.002160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao L, et al. Differential diagnosis of lung carcinoma with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2012;136:1502–1510. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0238-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanai N, et al. Intraoperative Confocal Microscopy for Brain Tumors: A Feasibility Analysis in Humans. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:ons282–ons290. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318212464e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barker J, Hoogi A, Depeursinge A, Rubin DL. Automated classification of brain tumor type in whole-slide digital pathology images using local representative tiles. Med Image Anal. 2016;30:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mousavi HS, Monga V, Rao G, Rao AU. Automated discrimination of lower and higher grade gliomas based on histopathological image analysis. Journal of pathology informatics. 2015;6:15. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.153914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1463–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleiss J, J C. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1973;33:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curry WT, Jr., Carter BS, Barker FG., 2nd Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in patient outcomes after craniotomy for tumor in adult patients in the United States, 1988-2004. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:427–437. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000365265.10141.8E. discussion 437-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith ER, Butler WE, Barker FG., 2nd Is there a "July phenomenon" in pediatric neurosurgery at teaching hospitals? J Neurosurg. 2006;105:169–176. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brinjikji W, Lanzino G, Cloft HJ. Cerebrovascular complications and utilization of endovascular techniques following transsphenoidal resection of pituitary adenomas: a study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2001-2010. Pituitary. 2014;17:430–435. doi: 10.1007/s11102-013-0521-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw and processed-image data generated in this work, including the representative images provided in the manuscript, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.