ABSTRACT

Communicating essential research information to low literacy research participants in Africa is highly challenging, since this population is vulnerable to poor comprehension of consent information. Several supportive materials have been developed to aid participant comprehension in these settings. Within the framework of a pneumococcal vaccine trial in The Gambia, we evaluated the recall and decay of consent information during the trial which used an audio-visual tool called ‘Speaking Book’, to foster comprehension among parents of participating infants. The Speaking Book was developed in the 2 most widely spoken local languages.

Four-hundred and 9 parents of trial infants gave consent to participate in this nested study and were included in the baseline assessment of their knowledge about trial participation. An additional assessment was conducted approximately 90 d later, following completion of the clinical trial protocol.

All parents received a Speaking Book at the start of the trial. Trial knowledge was already high at the baseline assessment with no differences related to socio-economic status or education. Knowledge of key trial information was retained at the completion of the study follow-up. The Speaking Book (SB) was well received by the study participants. We hypothesize that the SB may have contributed to the retention of information over the trial follow-up. Further studies evaluating the impact of this innovative tool are thus warranted.

KEYWORDS: Africa, decay, Informed consent, knowledge, recall, speaking book

Introduction

Individual agreement, or informed consent, is a process by which a potential participant voluntarily confirms his or her willingness to participate in a clinical trial after having received necessary information about all aspects relevant to inform this decision. This is a critical requirement for participation in biomedical research and should include a demonstration of recall of the purpose of the trial, potential benefits and harm, and participants' obligations and responsibilities.1 The informed consent process does not end at signing off the consent form, but continues throughout the trial,2,3 and participants need to understand their rights including withdrawal at any time without the need to give a reason for doing so.

When clinical trials are conducted in populations with low literacy levels, the process of informed consent encounters several challenges related but not limited to the basic principles of autonomy, voluntariness and comprehension. It is especially difficult for illiterate participants to appreciate how clinical trials differ from medical care, since investigators perform research procedures with the same medical instruments that are used in standard care.4-6 The perceived authority of a physician in these settings also often makes potential participants reluctant to ask questions or express unwillingness to participate in the trial.7 In addition, misunderstanding of trial procedures such as randomization8 are common.

There are particular challenges faced during the consent process in sub-Saharan Africa, given the combination of low level of literacy in the population and high number of spoken rather than written local languages. In many instances in these settings, the ICD is written in English or the corresponding official language of the country and, for illiterate participants, it is verbally interpreted by trained study staff during the consent process using their spoken language.9 Consent of illiterate participants is also supported by the presence of a literate impartial witness who should be present throughout the discussion to attest that the information discussed is consistent with the ICD and the process follows internationally acceptable ethical standards. The literate witness should be independent of the trial and should read and translate any written information supplied to the potential participant.1 Identifying and recruiting independent, literate witnesses poses an additional challenge.

To enable research participants to make an informed decision based on understanding of consent information, several innovative techniques have been developed. These include use of flower diagrams, flip charts with pictures, audio or audio-visual recordings and person-to-person discussions among others.3,10-13 Speaking Books (SB) have been developed to aid understanding and recall of trial information in low literacy communities. The SB is A5 size, has hard covers and large pages with each page of the book graphically illustrated with simple text relevant to the illustration. Every SB also has a plastic panel with a built in battery, which hosts a series of push buttons, each of which corresponds to a specific page in the speaking book. When activated, the ‘push buttons’ trigger a soundtrack of the text on the relevant page. The soundtrack is narrated by a native speaker with the appropriate voice and tonal quality, and is thus vocalised to the person using the book.14 SB have been piloted among English speakers14,15 but no study has examined their role when provided in participants' local languages despite the fact that the book has been translated into several local languages in Africa and Asia.

The nested study presented here assessed the recall of parents of infants participating in a pneumococcal vaccine trial in a peri-urban setting in The Gambia, West Africa. This study was nested within a phase III randomized, open-label trial aimed at evaluating the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) formulated in multi-dose vials given with routine pediatric vaccinations in healthy infants.16 The adult female literacy rate in this setting is about 30%17 and health-seeking behavior is governed by traditions rather than modern health care norm.18 We also assessed factors associated with decay of knowledge of key information relating to the parent trial19 during the 3 month follow-up period using a descriptive study design. The consent process for the parent trial used the SB with information delivered in the main local languages in Western Gambia – Wollof and Mandinka.

Results

Between January and May 2014, 500 infants were recruited for the parent trial. 428 parents (85.6%) were approached for this nested study and 409 (95.6%) parents (all mothers in this case) gave oral consent to answer the questions of the Additional questionnaire (AQ) in addition to the Assessment of consent recall questionnaire (ACQ). The analysis was performed on information available at the 2 time points assessed from 377 respondents (92.1%).

Most respondents were unemployed women (70.6%); 17.2% had no formal education, over 40% had 5 or fewer years of formal education and approximately 3 quarters were in a monogamous family (Table 1),

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristicsof mothers of infants enrolled to answer additional questions on consent during parent trial.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age groups of Respondent (years) | |

| 18–24 | 147 (39.0%) |

| 25–29 | 104 (27.6%) |

| 30+ | 126 (33.4%) |

| Occupation | |

| Civil Servant | 14 (3.7%) |

| Farming | 1 (0.3%) |

| Others | 29 (7.7%) |

| Trading | 67 (17.8%) |

| Unemployed | 266 (70.6%) |

| Years Of Education | |

| 0 | 65 (17.2%) |

| 1–5 | 90 (23.9%) |

| 6–10 | 140 (37.1%) |

| 11–14 | 75 (19.9%) |

| 15+ | 7 (1.9%) |

| Family Type | |

| Monogamy | 273 (72.4%) |

| Polygamy | 100 (26.5%) |

| Single Parent | 4 (1.1%) |

| Total | 377 |

For the 10 ACQ questions, over 99% of women during pre-trial assessment answered all of the questions correctly at the first attempt and the remaining 1% at the second attempt. At the end of the trial, all women responded correctly to the 10 questions in the only attempt given (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of consent recall and decay in knowledge between visit 1 (D0) and visit 4 (D 90).

| Question | Day 0 (pre-trial) | Day 90 (post trial) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questions requiring correct answers before trial enrolment (ACQ) | |||

| N | 377 | 377 | |

| This study will assess the pneumococcal vaccine already used in Gambia. (attempts) | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 376 (99.7%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Your child will receive trial vaccines on 2 occasions during the study. (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| This study requires that you come to the clinic for a total of 4 visits. (attempts) | 0.25 | ||

| 1 | 374 (99.2%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 3 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| This new vaccine will protect your child against polio. (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| A participant in this trial may receive the trial vaccine (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 1 teaspoon of blood will be collected from your child at the 4th visit. (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| You are free to withdraw from this study at any time. (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Study nurses can tell anyone about your participation in the study (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| You will be visited by a field worker for 5 d after each vaccination (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Your child's participation in the study will be for a period of 4 months (attempts) | 0.50 | ||

| 1 | 375 (99.5%) | 377 (100.0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Additional questions to assess consent recall and decay (AQ) | |||

| Vaccines will help to protect your child against getting diseases caused by germs. | 0.75 | ||

| False | 4 (1.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | |

| True | 373 (98.9%) | 371 (98.4%) | |

| How Many Babies need to be Recruited, n (%) | 0.53 | ||

| (10–400) | 37 (9.8%) | 43 (11.4%) | |

| 500 | 333 (88.3%) | 330 (87.5%) | |

| (600–2000) | 7 (1.9%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| When your child receives vaccines his/her body produces super heroes to fight infection | 0.049 | ||

| False | 6 (1.6%) | 16 (4.2%) | |

| True | 371 (98.4%) | 361 (95.8%) | |

| Your child will not receive other vaccines for his/her age while in the study | 0.081 | ||

| False | 268 (71.1%) | 290 (76.9%) | |

| True | 109 (28.9%) | 87 (23.1%) | |

| You can request a form to take home and discuss with your family | 0.75 | ||

| False | 6 (1.6%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| True | 371 (98.4%) | 373 (98.9%) | |

| A malaria test will never be done if your child develops fever | <0.001 | ||

| False | 305 (80.9%) | 357 (94.7%) | |

| True | 72 (19.1%) | 20 (5.3%) | |

| Which other person can sign the consent form? | 0.77 | ||

| Husband | 348 (92.3%) | 353 (93.6%) | |

| Mother | 9 (2.4%) | 8 (2.1%) | |

| Other | 20 (5.3%) | 16 (4.2%) | |

| Babies may have pain but not swelling when a vaccine is given | 0.24 | ||

| False | 70 (18.6%) | 57 (15.1%) | |

| True | 307 (81.4%) | 320 (84.9%) | |

| The doctor will stop the study for your child if he/she thinks that your baby could be hurt | <0.001 | ||

| False | 50 (13.3%) | 10 (2.7%) | |

| True | 327 (86.7%) | 367 (97.3%) | |

| If your baby is unwell 5 d after vaccination he must be admitted to hospital. | <0.001 | ||

| True | 47 (12.5%) | 9 (2.4%) | |

| False | 330 (87.5%) | 368 (97.6%) |

For the AQ, which was specific for the nested study, the frequency of correct answers was lower with 6 out of 10 questions having less than 90% of correct answers pre-trial; and only 2 out of 10 post-trial. Questions with double negative statements like ‘Your child will not receive other vaccines for his/her age while in the study’ were answered correctly by 71.1% of women pre-trial and 76.9% post-trial compared with over 98% correct responses at both time points, for more straightforward questions like ‘You can request a form to take home and discuss with your family’ (Table 2). Overall, the proportion of correct answers post-trial was higher than pre-trial, with significant differences for “A malaria test will never be done if your child develops fever” (pre: 80.9% correct versus post: 94.7%, p < 0.001); “the doctor will stop the study for your child if s/he thinks that your baby could be hurt” (pre: 86.7% correct vs. post: 97.3%, p < 0.001) and “If your baby is unwell 5 d after vaccination he/she must be admitted to hospital” (pre: 87.5% correct vs. post: 99.6%, p < 0.001).

No differences in level of trial knowledge were found by age, occupation, years of education, religion or family type either at pre or post-trial (Table 3). A difference between time points was only observed as an increase in knowledge among farmers (from 75% to 90%), which was the group with lowest knowledge pre-trial. This difference was however not statistically significant as the confidence intervals at both time points overlapped and the 95% confidence interval for the mean difference just crosses 0 (−30.2 – 0.2).

Table 3.

Assessment of consent recall and decay in knowledge based on socioeconomic parameters.

| Day 0 (pre trial) |

Day 90 (post trial) |

Difference (Visit1-Visit4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean(95%CI) | P value | Mean(95%CI) | P value | Mean(95%CI) |

| Age of Respondent (years) | 0.570 | 0.768 | |||

| 18–24 | 87.8(86.7; 88.9) | 89.3(88.6; 90.0) | −1.5(−2.7; −0.2) | ||

| 25–29 | 88.7(87.4; 90.0) | 89.0(88.2; 89.8) | −0.3(−1.8; 1.2) | ||

| 30+ | 89.8(88.6; 91.1) | 89.0(88.3; 89.7) | 0.8(−0.5; 2.2) | ||

| Occupation | 0.144 | 0.821 | |||

| Civil Servant | 89.6(86; 93.3) | 88.9(86.7; 91.1) | 0.7(−3.4; 4.8) | ||

| Farming | 75.0(61.4; 88.6) | 90.0 (81.8; 98.2) | −15.0(−30.2; 0.2) | ||

| Other | 86.7(84.2; 89.2) | 88.6(87.1; 90.1) | − 1.9(−4.7; 0.9) | ||

| Trading | 89.1(87.4; 90.8) | 89.6(88.6; 90.6) | − 0.5 (−2.4; 1.3) | ||

| Unemployed | 88.9(88.0; 89.7) | 89.1(88.6; 89.6) | − 0.2 (−1.1; 0.7) | ||

| Education Level | 0.786 | 0.14 | |||

| Arabic Only | 89.3(88; 90.7) | 88.5(87.7; 89.3) | 0.8(−0.7; 2.3) | ||

| None | 88.5(86.8; 90.2) | 89.1(88.1; 90.1) | −0.6(−2.5; 1.3) | ||

| Part Primary | 87.9(85.3; 90.4) | 88.8(87.2; 90.3) | −0.9(−3.8; 2) | ||

| Part Secondary | 88.8(87.4; 90.1) | 89.8(89.0; 90.5) | −1.0(−2.5; 0.4) | ||

| Part Tertiary | 86.9(82.0; 91.7) | 86.9(84.0; 89.7) | 0.0(−5.4; 5.4) | ||

| Primary | 85.9(81.8; 90) | 90.9(88.5; 93.4) | −5.0(−9.6; −0.4) | ||

| Secondary | 89.4(87.2; 91.6) | 88.7(87.4; 90) | 0.6(−1.8; 3.1) | ||

| Tertiary | 89.0(85.5; 92.5) | 90.3(88.2; 92.4) | −1.3(−5.3; 2.6) | ||

| Years Of Education (caretaker) | 0.86 | 0.496 | |||

| 0 | 88.5(86.8; 90.2) | 89.1(88.1; 90.1) | −0.6(−2.5; 1.3) | ||

| 1–5 | 89.2(87.7; 90.6) | 88.7(87.9; 89.6) | 0.4(−1.2; 2.1) | ||

| 6–10 | 88.3(87.2; 89.5) | 89.5(88.8; 90.2) | −1.1(−2.4; 0.1) | ||

| 11–14 | 89.2(87.6; 90.8) | 89.2(88.3; 90.1) | 0.0(−1.8; 1.8) | ||

| 15+ | 89.3(84.1; 94.5) | 87.1(84.1; 90.2) | 2.1(−3.6; 7.9) | ||

| Religion | 0.252 | 0.524 | |||

| Christianity | 86.1(81.6; 90.7) | 90.0(87.3; 92.7) | −3.9(−9.0; 1.2) | ||

| Islam | 88.8(88.1; 89.5) | 89.1(88.7; 89.5) | −0.3(−1.1; 0.5) | ||

| Family Type | 0.808 | 0.257 | |||

| Monogamy | 88.6(87.8; 89.4) | 89.1(88.6; 89.6) | −0.5(−1.4; 0.4) | ||

| Polygamy | 89.1(87.7; 90.4) | 89.0(88.2; 89.8) | 0.1(−1.5; 1.6) | ||

| Single Parent | 90.0(83.2; 96.8) | 92.5(88.4; 96.6) | −2.5(−10.1; 5.1) | ||

Participant responses to open ended questions

Most women (95.5%) did not recommend any change. Among those suggesting improvements (multiple answers permitted), the most common suggestions were addition of other local languages such as Fula, or Jola (2.7%); followed by increasing the speaker volume (0.8%), the need for extra batteries (0.5%) and reduction in the size of the book (0.5%). 97.9% shared the book with other family and friends.

The key messages stated by respondents to the open ended questions relating to their recall from the SB are summarized as follows;

-

1)

It provided a better recall of research ethics e.g. [“your child's confidential information will be protected," “it is your decision to participate in the trial”].

-

2)

It provided a better recall of clinical research e.g., [“the field worker will visit for 5 d after vaccination, “checking the blood is the most important part to me because without this it's impossible to know what effect the vaccine has had”].

-

3)

It provided information on improving child health e.g., [“attending monthly maternal child health clinics for vaccination can improve the health of your child”],

-

4)

It explained the importance of vaccination e.g., [“I now understand why we take our children for the monthly clinics and the importance of participating in research studies," “monthly vaccination is important, can protect your child from diseases]

-

5)

It stimulated interest in the trial e.g., [One 25year old respondent said “I listened to the book in my neighbors' home and decided to come and find out more about the trial”].

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that trial participants receiving a speaking book had a good knowledge of the trial procedures at the start of the trial and retained this information during the 90 d of trial procedures.

Although trial information was generally well understood, the answers to more difficult questions, such as those with double negative statements or related to clinical care, were less accurate (70–80% correct answers compared with over 90%). This is probably a consequence of the generally low educational levels in our study population. In both developed and developing country contexts it has been shown that educational level was an independent predictor of comprehension.20,21 In contrast, however, educational level was not associated with comprehension in our study as previously shown in The Gambia, within a largely illiterate population.22,23 It may be that differences in education within the study population are too lean to detect differences and is a subject for future research.

Interestingly, we noted that there was a trend of improvement of trial knowledge over the course of the follow-up period for all age groups, occupations, educational levels, religions and family types. We speculate that this trend (though not statistically significant) may, in part, have been due to the use of the SB which encouraged continuous exposure to key trial information.23 Our statement is supported by the reports of high SB use and the sharing of the SB with other family members and friends which implies continuous exposure to the trial information. Studies with comparator groups where some participants do not receive the SB would however be necessary to confirm this hypothesis as mere participation in the trial and other trial procedures could also account for this trend. Previous studies which have assessed the use of multimedia tools10,22 to assess recall of key trial information one week after initial consent have also shown improvements in trial participants knowledge of clinical trials, and their rights and responsibilities. Our study differs as the follow-up period was longer (90 days) compared with the shorter follow-up of 1 week in other studies.

Most of the women appeared satisfied with the SB and did not suggest any improvements (95.5%). Among suggested improvements were changes to portability of the book and increased battery life. The suggestion to include other major oral languages in the SB, although ideal, it would be impractical for logistical reasons due to the number of minor languages in the country. Still, in countries with several local languages the limitation of the number of languages to be added to the SB would always be a limitation to consider. We also observed that the SB is an additional tool for expanding the information of an ongoing trial in the community, based on the responses of one of our trial participants indicating that she first heard about our trial at a neighbors' home by listening to her SB.

Beyond the limitations of the SB, this ancillary study has some limitations based on the study design, given that all study participants had access to the SB before the assessment and thus there was no comparator group to assess the real advantages of the book. We only included participants who had passed the baseline assessment to the parent trial. We note however that only 2 out of 526 participants were excluded from the main trial for failing the baseline comprehension test. In addition, the follow-up period was short and studies with longer follow up may reveal some decay in consent information. The population in the Gambia also has long-term exposure to clinical research with the presence of the Medical Research council Unit for over 70 y. This may also have impacted understanding and subsequent recall of information.

Conclusion

The awareness of trial information was generally high in this illiterate population.

There was no apparent decay in consent information or change in recall in any of the sociodemographic subgroups.

The SB has potential to educate low literacy communities regarding participation in clinical trials in settings where written language translation is a challenge and may have benefits beyond education for the specific trial.

Methods

Study design and population

The parent trial enrolled healthy infants aged 42 to 70 d weighing 3·5 kg or more who presented for vaccination at Fajikunda Major Health Centre (FKHC), a government run health facility in western Gambia that vaccinates approximately 5,000 children per year. Details of entry and exclusion criteria are available at (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01964716). Children were recruited before the first dose of PCV13 and were visited daily for 5 d after each vaccination to assess for local and systemic adverse vaccine reactions, and seen monthly at the health facility until one month after the third dose of PCV13. Parents who gave consent for their infants to participate in the trial were approached to participate in this descriptive nested study.

Consent process

Community leaders including household heads, women and youth leaders and local religious leaders were visited to give information regarding the trial. This was followed by large community sensitization meetings at which the trial team explained key trial information and addressed concerns raised on the cultural and social appropriateness of some of the trial procedures such as frequency of appointments and what each clinic/home visit would entail.

The trial staff subsequently approached potential participants at the Infant Welfare clinic located within FKHC, and held discussions about the parent trial with parents who brought their infants for routine immunisations/care. The parents were encouraged to seek clarity on any aspect of the parent trial. The trial staff then asked the parent a set of questions to ensure understanding, and provided a copy of the ICD to be taken home to discuss with other family members. These steps are in accordance with the routine consent process for trials of this nature in this setting.

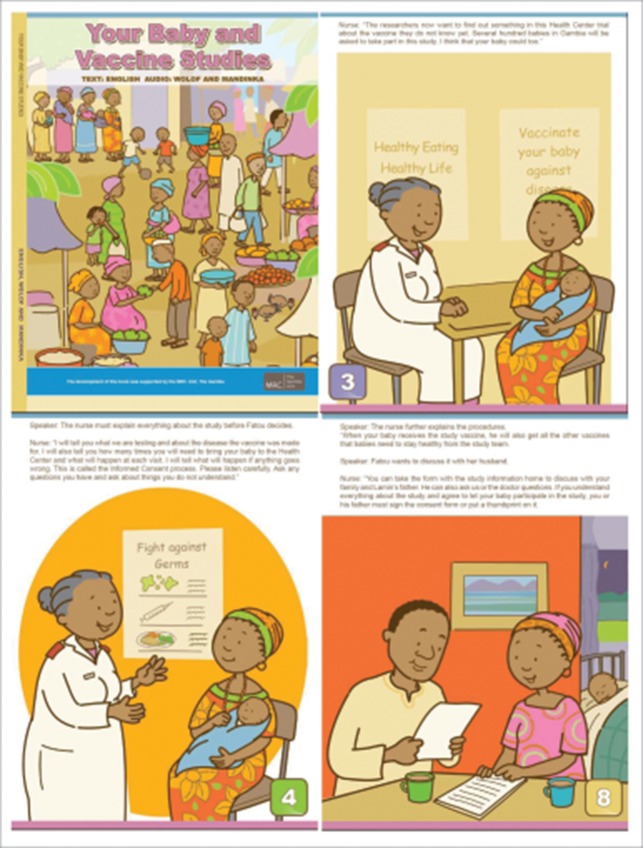

Following this, meetings to discuss the contents of the ICD and answer any questions from other family members identified by the parent were arranged. Individuals who continued to express willingness to participate in the study received a copy of the SB as required by the parent trial. The SB was developed in 2 major Gambian languages: - Mandinka and Wolof. The book explained in clear local dialect the basic elements of the trial participation including trial purpose, participant rights, and their roles and responsibilities (Figure 1). The research staff further explained to parents who gave consent how to use the book, including how to switch between the 2 local language recordings.

Figure 1.

Excerpt from speaking book: Front cover and select pages. © Pfizer. Reproduced by permission of Pfizer. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

Parents were then requested to visit the FKHC for informed consent procedure (including another explanation of the consent document and an opportunity to ask questions). Assessment of eligibility was also performed by the trial clinicians during this visit. Consent information was given only in Mandinka, Wolof or English, based on participant preference.

Following these procedures, participant recall of key trial information was assessed using an interviewer-administered Assessment of Consent recall Questionnaire (ACQ).

The ACQ was a 10-item questionnaire with a ‘true’ or ‘false’ response. Domains covered by this questionnaire included purpose of the trial, confidentiality, voluntariness and trial procedures. A score of 1 was assigned for each question answered correctly and 0 for questions answered incorrectly. If the total score was 10 the participant was enrolled. If the score was 9, the question wrongly answered was reviewed with the parent and the participant enrolled. A score of 8 or below required a review of trial information followed by a second attempt at the ACQ. If any error was made at the second attempt, the participant was not eligible for enrolment into the parent trial.

Parents of infants recruited in the parent trial were subsequently approached to participate in this nested study by giving oral consent. Where consent was given, an Additional Questionnaire (AQ) comprising of 10 question items (8 true or false and 2 open ended) was then administered on the day of enrolment) asking more in-depth questions regarding the trial. Only one attempt was allowed to respond at these questions and the results did not compromise the participation in the parent trial. Additional questions on experience of use of the SB were asked post trial (90 d post enrolment) along with the re- administration of the ACQ and AQ.

The knowledge of informed consent information was determined by the responses to questions in the 2 questionnaires.

This study used a speaking book narrated in the well known voice of a popular local media personality.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis

Data analysis

Twenty items from both questionnaires were used to assess the knowledge of participants, estimated by the proportion of correct responses given by the participants. Socio-demographic factors (age, education level, religion, family type and occupation) and each knowledge assessment item, all categorical, were summarized by proportion. Fisher's exact tests for association were applied to compare the proportions of correct answers for each item between visits.

Further, ordinary least square (OLS) linear regression analysis was applied to estimate and compare mean proportions of correct answers (with their 95% confidence intervals) between and within different levels of socio-demographic factors. Separate analyses were conducted at the 2 time points and for the paired differences between the 2 visits (knowledge decay). Overall p values of associations were estimated for the outcomes (visit one and visit 4), as well as specific p values for within socio-demographic group knowledge decay.

All analyses were conducted in Stata version 12 (StataCorp, USA). A 2-sided p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Open ended questions were analyzed through content analysis of participant responses.19

Ethical consideration

The Gambia Government/MRC Joint Ethics Committee approved the parent trial and this nested study. Written informed consent was obtained for parent trial while verbal consent was obtained for the nested study. Participation was voluntary and confidentiality maintained.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the field team led by Abdou Gibba and Jereba Darboe, the Fajikunda Health centre The Gambia who hosted the study and the study communities and participants. Thanks to Alejandra Gurtman, France Laudat, Kimberley Center and Lisa Pereira at Pfizer for the development and introduction of the speaking book and collaboration on development of the overall consent process. We also acknowledge the Medical Research Council's Clinical Trial Support Office led by Jenny Mueller and Research Support office led by Elizabeth Batchilly and Adrameh Gaye for their contribution to the development of the speaking book and James Jafali for statistical advice.

Funding

The parent trial was funded by Pfizer Inc.

References

- [1].Expert Working Group. Guidance for Industry E6 Good Clinical Practice; Consolidated Guidance; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) 1996. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm073122.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [2].Scott S, Odutola A, Mackenzie G, Fulford T, Afolabi MO, Lowe Jallow Y, Jasseh M, Jeffries D, Dondeh BL, Howie SR, et al.. Coverage and timing of children's vaccination: an evaluation of the expanded programme on immunisation in The Gambia. PLoS One 2014; 9(9):e107280; PMID:25232830; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0107280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vallely A, Lees S, Shagi C, Kasindi S, Soteli S, Kavit N, Vallely L, McCormack S, Pool R, Hayes RJ. How informed is consent in vulnerable populations? Experience using a continuous consent process during the MDP301 vaginal microbicide trial in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Med Ethics 2010; 11:10; PMID:20540803; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1472-6939-11-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Miller FG RD. The therapeutic orientation to clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2003; 14(348):1383-6; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMsb030228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pappelbaum PS RL, Lidz CW, Benson P, Winslade W. False Hopes and Best Data: Consent to research and the Therapeutic misconception. Hestings Center Report 1987; 17(2):20-4; https://doi.org/ 10.2307/3562038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Niels Lynoe MS, Dahlqvist G, Jacobsson L. informed consent; study of quality of information given to participants in a clinical trial BMJ 1991; 303:610-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fitzgerald DW, Marotte C, Verdier RI, Johnson WD, Pape JW. Comprehension during informed consent in a less-developed country. Lancet 2002; 360(9342):1301-2; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11338-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Carvalho AA, Costa LR. Mothers' perceptions of their child's enrollment in a randomized clinical trial: Poor understanding, vulnerability and contradictory feelings. BMC Med Ethics 2013; 14:52; PMID:24325658; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1472-6939-14-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yauba S. Contextualizing the informed consent process in vaccine trials in developing countries. J Clin Res Bioethics 2013; 04:01; https://doi.org/ 10.4172/2155-9627.1000141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Castelnuovo B, Newell K, Manabe YC, Robertson G. Multi-Media Educational Tool Increases Knowledge of Clinical Trials in Uganda. J Clin Res Bioeth 2014; 5:165; PMID:24795832; https://doi.org/ 10.4172/2155-9627.1000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sonne SC, Andrews JO, Gentilin SM, Oppenheimer S, Obeid J, Brady K, Wolf S, Davis R, Magruder K. Development and pilot testing of a video-assisted informed consent process. Contemp Clin Trials 2013; 36(1):25-31; PMID:23747986; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bhutta ZA. Beyond informed consent. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 2004; 82: 771–777 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wood SY, Friedland BA, McGrory CE. Informed consent: From good intentions to sound practices: A report of a seminar. New York: Population Council; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dhai A, Etheredge H, Cleaton-Jones P. A pilot study evaluating an intervention designed to raise awareness of clinical trials among potential participants in the developing world. J Med Ethics 2010; 36(4):238-42; PMID:20338937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Castelnuovo B, Newell K, Manabe YC, Robertson G. Multi-media Educational Tool Increases Knowledge of Clinical Trials in Uganda. J Clin Res Bioethics 2014; 5:165; PMID:24795832; https://doi.org/ 10.4172/2155-9627.1000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Idoko O, Mboizi R, Okoye M, Laudat F, Ceesay B, Liang J, Ledren-Narayanin N, Jansen K, Gurtman A, Center K, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) formulated with 2-phenoxyethanol in multidose vials given with routine vaccination in healthy infants: An open-label randomized controlled trial. Vaccine 2017; (e-published ahead of print); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].The Gambia Demographic Profile 2013. Available at: http://www.indexmundi.com/the_gambia/demographics_profile.html (accessed 3 May 2014) [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fairhead J, Leach M, Small M. Public engagement with science? Local understandings of a vaccine trial in the Gambia. J Biosoc Sci 2006; 38(1):103-16; PMID:16266443; https://doi.org/ 10.1017/S0021932005000945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Philipp M. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qulitative Social Res 2000; 1:2. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hutchison C, Cowan C, McMahon T, Paul J. A randomised controlled study of an audiovisual patient information intervention on informed consent and recruitment to cancer clinical trials. Br J Cancer 2007; 97(6):705-11; PMID:17848908; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hutchison C, Cowan C, Paul J. Patient understanding of research: developing and testing of a new questionnaire. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2007; 16(2):187-95; quiz 195-6; PMID:17371430; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Afolabi MO, Bojang K, D'Alessandro U, Imoukhuede EB, Ravinetto RM, Larson HJ, McGrath N, Chandramohan D. Multimedia Informed Consent Tool for a Low Literacy African Research Population: Development and Pilot-Testing. J Clin Res Bioeth 2014; 5(3):178; PMID:25133065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Afolabi MO, McGrath N, D'Alessandro U, Kampmann B, Imoukhuede EB, Ravinetto RM, Alexander N, Larson HJ, Chandramohan D, Bojang K. A multimedia consent tool for research participants in the Gambia: a randomized controlled trial. Bulletin World Health Organization 2015; 93:320-328A; https://doi.org/ 10.2471/BLT.14.146159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dhai A, Etheredge H, Cleaton-Jones P. A pilot study evaluating an intervention designed to raise awareness of clinical trials among potential participants in the developing world. J Med Ethics 2010; 36(4):238-42; PMID:20338937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]