Abstract

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse can significantly reduce quality of life of affected women, with many cases requiring corrective surgery. The rate of recurrence is relatively high after conventional prolapse surgery. In recent years, alloplastic meshes have increasingly been implanted to stabilize the pelvic floor, which has led to considerable improvement of anatomical results. But the potential for mesh-induced risks has led to a controversial discussion on the use of surgical meshes in urogynecology. The impact of cystocele correction and implantation of an alloplastic mesh on patientsʼ quality of life/sexuality and the long-term stability of this approach were investigated.

Method

In a large prospective multicenter study, 289 patients with symptomatic cystocele underwent surgery with implantation of a titanized polypropylene mesh (TiLOOP ® Total 6, pfm medical ag) and followed up for 36 months. Both primary procedures and procedures for recurrence were included in the study. Anatomical outcomes were quantified using the POP-Q system. Quality of life including sexuality were assessed using the German version of the validated P-QoL questionnaire. All adverse events were assessed by an independent clinical event committee.

Results

Mean patient age was 67 ± 8 years. Quality of life improved significantly over the course of the study in all investigated areas, including sexuality and personal relationships (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test). The number of adverse events which occurred in the period between 12 and 36 months after surgery was low, with just 22 events reported. The recurrence rate for the anterior compartment was 4.5%. Previous or concomitant hysterectomy increased the risk of recurrence in the posterior compartment 2.8-fold and increased the risk of erosion 2.25-fold.

Conclusion

Cystocele correction using a 2nd generation alloplastic mesh achieved good anatomical and functional results in cases requiring stabilization of the pelvic floor and in patients with recurrence. The rate of recurrence was low, the patientsʼ quality of life improved significantly, and the risks were acceptable.

Key words: alloplastic mesh, pelvic organ prolapse, quality of life, sexuality, POP-Q

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung Der Descensus genitalis kann die Lebensqualität erheblich einschränken. In vielen Fällen ist deshalb eine operative Korrektur erforderlich. Da die Rezidivrate bei der konventionellen Deszensuschirurgie recht hoch ist, wurden in den letzten Jahren zunehmend alloplastische Netze zur Stabilisierung eingesetzt. Die anatomischen Resultate konnten hierdurch deutlich verbessert werden. Die möglichen netzinduzierten Risiken haben zu einer kontroversen Diskussion über deren Einsatz geführt. In einer großen multizentrischen Studie wurde der Einfluss einer Netzimplantation zur Zystozelenkorrektur auf die Lebensqualität/Sexualität, und Langzeitstabilität untersucht.

Methode 289 Patientinnen mit symptomatischer Zystozele wurden in einer prospektiven Studie mit einem titanisierten Polypropylennetz (TiLOOP ® Total 6, pfm medical ag) operiert und 36 Monate nachbeobachtet. Sowohl Primär- als auch Rezidiveingriffe wurden berücksichtigt. Das anatomische Resultat wurde mittels POP-Q-System quantifiziert. Die Lebensqualität inkl. Sexualität wurde mit dem validierten P-QoL-Fragebogen erfasst. Alle unerwünschten Ereignisse wurden von einem unabhängigen Komitee bewertet.

Ergebnisse Das Durchschnittsalter der Patientinnen betrug 67 ± 8 Jahre. Die Lebensqualität verbesserte sich im Verlauf der Studie signifikant in allen untersuchten Bereichen, auch hinsichtlich der Sexualität und Partnerschaft (p < 0,001, Wilcoxon-Test). Die Anzahl unerwünschter Ereignisse zwischen 12 und 36 Monaten war mit 22 Meldungen gering. Die Rezidivrate im anterioren Kompartiment betrug 4,5%. Eine vorbestehende oder begleitend durchgeführte Hysterektomie erhöhte das Risiko eines Rezidivs im posterioren Kompartiment um das 2,8-Fache, das einer Erosion um das 2,25-Fache.

Schlussfolgerung Die Zystozelenkorrektur mit einem alloplastischen Netz der 2. Generation erzielt in Fällen von gewünschter Stabilität oder in der Rezidivsituation ein gutes anatomisches und funktionelles Ergebnis. Die Rezidivrate ist gering, die Lebensqualität verbessert sich signifikant und die Risiken sind vertretbar.

Schlüsselwörter: alloplastisches Netz, Beckenbodensenkung, Lebensqualität, Sexualität, POP-Q

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse can significantly reduce the quality of life of affected women 1 . The most serious effect of pelvic organ prolapse is impairment of bladder and bowel function accompanied by incontinence and voiding disorders 2 , 3 . General well-being, personal relationships, particularly sexuality 4 , and physical and social activities often suffer from the effects of prolapse 5 , 6 . The incidence of pelvic organ prolapse in women has increased in parallel with the general increase in life expectancy, and the likelihood that women aged 80 years will require surgical intervention (e.g. hysterectomy, pelvic floor reconstruction) is 12.2% 7 . One in nine women is affected by prolapse 8 . Up to 30% of patients require a repeat operation for recurrence within 5 years of the original procedure 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 . Surgical correction of prolapse should not just reposition the prolapsed pelvic organs, it should also restore the patientʼs quality of life or at least improve it. As the recurrence rate after conventional anterior colporrhaphy with autologous tissue is high 1 , 13 , the aim is to improve the long-term stability of the pelvic floor through implantation of an alloplastic mesh. A Cochrane analysis of the data on alloplastic meshes in prolapse surgery showed significantly better results in terms of anatomical outcome 14 . But, particularly with 1st generation implants, a number of new adverse events occurred following the implantation of alloplastic meshes and included vaginal erosion, pain and dyspareunia 15 . These mesh-induced risks 16 have led to the benefits of alloplastic materials for patients in prolapse surgery still being controversially discussed, despite the positive data on the long-term stability reported in the Cochrane analysis. Improvements to the procedure such as lighter meshes, the improvement of dissection techniques, better apical fixation and the increased experience of surgeons has succeeded in significantly reducing the rate of complications 1 . This has also been confirmed by previously published results of the study reported on here 5 , 6 . This prospective study on the implantation of an alloplastic mesh aimed to investigate anatomical outcomes and the impact on patientsʼ quality of life over a period of 36 months. The final results for quality of life, sexuality, and anatomical outcomes are now available.

Material and Method

Patients and study design

This prospective study was carried out at nine German hospitals (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01084889). A total of 292 patients with cystocele or pelvic organ prolapse ≥ grade II (ICS [International Continence Society] classification using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification [POP-Q] system) or with grade I prolapse and symptoms requiring surgical intervention were included in the study. The study included both primary procedures and surgery for recurrence. Exclusion criteria were defined as status post pelvic radiation, status post mesh implantation in the anterior compartment, and previous systemic steroid therapy. Patients were briefed in detail about the study and were able to understand the nature, goals, benefits, results and risks of the study. The study participants had the right to revoke their consent at any time. Patient data were anonymized in accordance with the German Data Protection Act, making it impossible for third persons to identify patients. The multicenter study was only started after the study had been publicly registered in the registry of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the ethical votes required by the professional code were available for every participating center. The study was followed by 100% monitoring and supervision through external auditing.

Patients were examined at 6, 12 and 36 months postoperatively. The anatomical results were assessed using the POP-Q system 17 . Patientsʼ quality of life was recorded using the Prolapse Quality-of-Life (P-QoL) questionnaire 18 , 19 .

In addition to the primary (erosion rate after 12 months, quality of life after six months) and secondary study objectives (adverse events at six, 12 and 36 months, quality of life at 12 and 36 months, feasibility of mesh implantation), sexual function and the anatomical results over the course of the study were also analyzed.

Surgical method and mesh implant

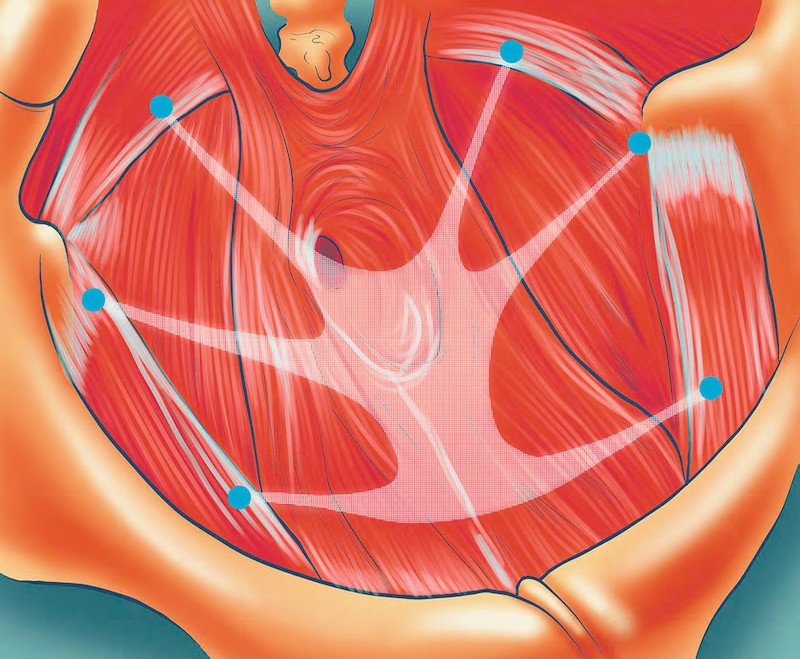

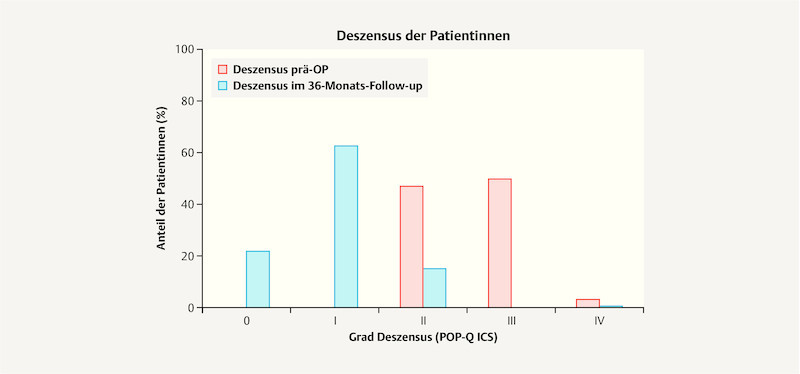

Cystocele correction was done using a vaginal approach with implantation of a titanized polypropylene mesh (TiLOOP ® Total 6, pfm medical ag) with a pore size > 1 mm. After performing a longitudinal incision of the anterior vaginal wall with dissection of the cystocele, the 6-armed mesh was placed using a tunneler for a transobturator and ischiorectal approach and fixed distally, laterally and apically ( Fig. 1 ). Apical fixation was done at the sacrospinal ligament. Vaginal estrogenization and a single-dose antibiotic were prescribed and administered. Some patients also underwent additional surgical procedures, e.g. correction of the posterior compartment, hysterectomy, or placement of a suburethral sling, and the data for these procedures were also recorded.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing six-point fixation of the TiLOOP ® Total 6 mesh implant. The mesh is fixed without tension distally, laterally and apically using a transobturator und ischiorectal approach. Apical fixation was done at the sacrospinal ligament. Source: pfm medical ag.

Prolapse Quality-of-Life questionnaire to determine quality of life and sexual function

Quality of life was assessed preoperatively with the validated German version of the P-QoL questionnaire 18 , 19 and at six, 12 and 36 months after surgery. The questionnaire consists of 40 questions. Topics covered include questions on the patientʼs perception of their general state of health, the impact of the prolapse, role limitations and physical limitations, questions about patientsʼ personal relationships including sexuality, emotions, sleep and other limitations. The scale ranges from zero (no limitations) to 100 (lowest quality of life). The following three questions were evaluated separately in an attempt to assess the impact of mesh implants on the patientsʼ sex life:

Does the prolapse negatively affect your personal relationship?

Does the prolapse negatively affect your sex life?

Do you have a vaginal protrusion which makes sexual intercourse difficult?

Patients were free not to answer individual or all questions about their quality of life. For example, patients who were not sexually active when they completed the questionnaire because they did not have a partner or because of their age responded by ticking “no answer possible”.

Anatomical outcome

The anatomical result was defined preoperatively and over the course of the study using the POP-Q system. This system, which is now considered the standard international classification for prolapse surgery, was published by the ICS in 1996 17 . It assesses the location of the defective structures and quantifies the severity of the prolapse. Defined points in the anterior (Aa, Ba), apical (C, D; cervix or end of the vagina) and posterior compartment (Ap, Bp) are measured in terms of their distance to the hymenal ring. This validated system makes it possible to obtain a standardized, quantifiable and reproducible classification of the degree of pelvic organ prolapse 20 .

Clinical Event Committee

All adverse events recorded for the purposes of the study were presented to an independent external Clinical Event Committee (CEC) which assessed them using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 0.4) 21 . The experts in the committee were selected based on their medical and scientific experience and confirmed their independence by disclosing their (financial) interests.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS, version 22. Wilcoxon test was used for the statistical analysis of the difference in patientsʼ quality of life (including sexuality) between preoperative and the postoperative time points. Chi-square test was used for subgroup analysis of recurrence, and Mann-Whitney U-test was used for subgroup analysis of erosion, POP-Q values and quality of life.

Results

Demography

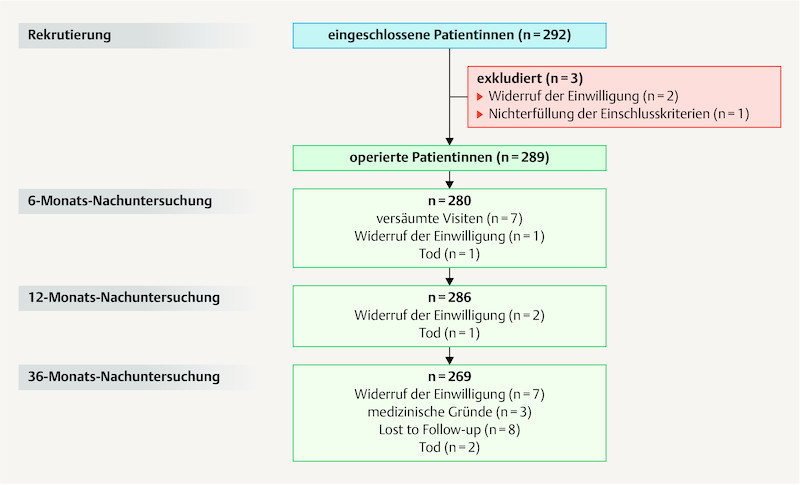

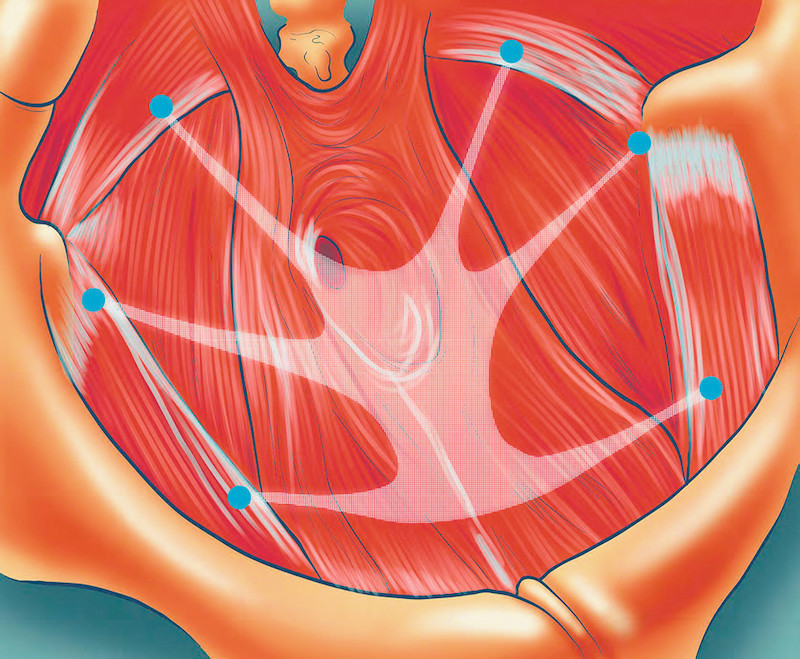

Between 2010 and 2012, 289 of the 292 patients included in the study underwent surgery. Two patients revoked their consent before the operation. Intraoperative findings in one patient who was originally included in the study showed that she did not require mesh implantation. Before the 6-month follow-up one patients revoked her consent for inclusion in the study, and one patient revoked her consent between the 6-month and 12-month follow-up. Five patients revoked their consent between the 12-month and the 36-month follow-up. Two patients died for reasons unconnected to the study. At six months, data was recorded for 280 patients, at 12 months data was recorded for 286 patients, and at 36 months data was recorded for 269 patients. Fig. 2 shows a chart of the patient population defined in accordance with the CONSORT 2010 Statement 22 .

Fig. 2.

Chart showing the patients who participated in the study as defined by the CONSORT 2010 Statement 22 .

Mean patient age was 67 ± 8 years (43 – 87 years), and mean BMI was 27 ± 4 kg/m 2 (17 – 37 kg/m 2 ). Mean number of children born to the patients was 2.3 ± 1.2 children. The demographic data of the operated patients corresponded to the mean of census data 23 or DRG (diagnosis-related groups) data from German hospitals 24 . 31.8% (92/289) of patients had had a hysterectomy; 14.9% (43/289) had previously been operated on for prolapse. 34.9% (101/289) of patients underwent conventional posterior colporrhaphy for correction of rectocele concomitantly with mesh implantation; 25.6% (74/289) had simultaneous placement of a posterior mesh and 36.3% (105/289) underwent concomitant hysterectomy.

Quality of life and sexuality

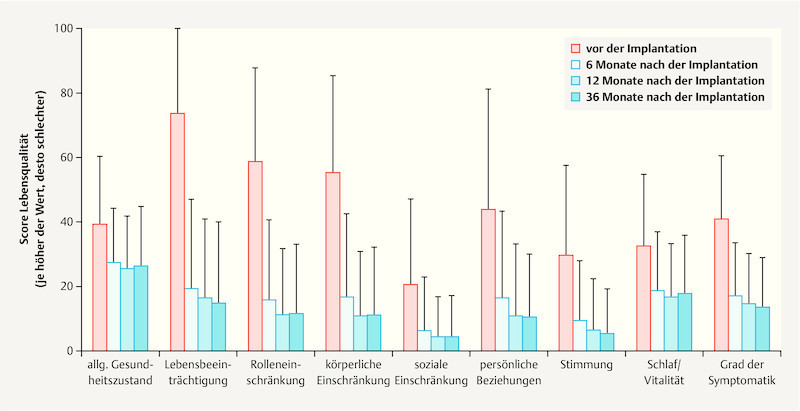

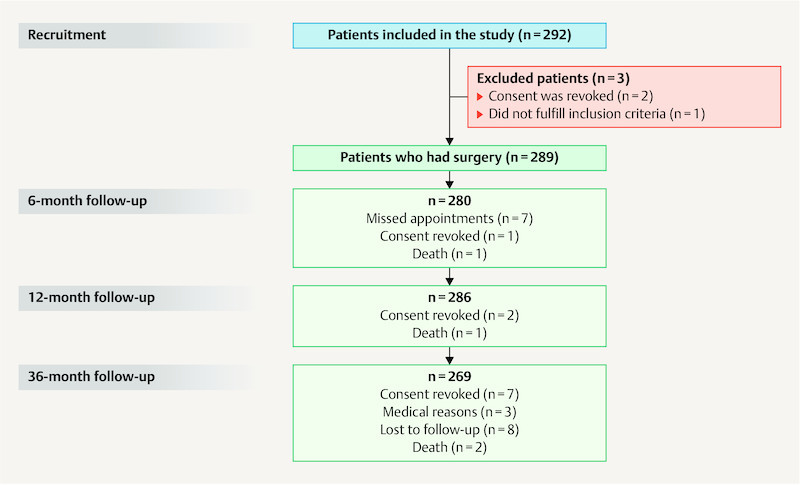

A significant improvement in quality of life was recorded over the course of the study (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 3 ). The strongest negative effect on patients in terms of the impact of the prolapse (73.5 of 100 points), the role limitations and physical limitations (58.5 and 55.0, respectively, out of 100 points), and the limitations on personal relationships (43.8 out of 100 points) was experienced preoperatively ( Table 1 , Fig. 3 ). A significant improvement (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test, Table 1 , Fig. 3 ) was recorded already after six months for the four areas listed above (19.4, 15.8 and 16.6, and 16.5, respectively, out of 100 points) as well as for five other investigated areas (general state of health: 39.3 vs. 27.2; social limitations: 20.6 vs. 6.0; emotions: 29.6 vs. 9.3; sleep/energy: 32.4 vs. 18.5; severity of symptoms: 40.8 vs. 17.1). The patients surveyed at 12 and 36 months continued to have a significantly better quality of life compared to their status prior to reconstruction of the pelvic floor (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test, Table 1 ). The results are summarized in Table 1 .

Fig. 3.

Quality of life before and after implantation of an alloplastic mesh. The bar chart shows the figures for quality of life at 6, 12 and 36 months after implantation compared to patientsʼ quality of life before the implantation, with 100 corresponding to the lowest quality of life. Quality of life was itemized into a number of different areas.

Table 1 Quality of life before and after implantation of an alloplastic mesh based on the validated P-QoL questionnaire 19 . The higher the recorded figure, the lower the quality of life. Mean values and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for the preoperative period, and at 6, 12 and 36 months after implantation.

| Preoperatively | At 6 months | p-value | At 12 months | p-value | At 36 months | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| General state of health | 39.3 | 21.0 | 27.2 | 17.0 | < 0.001 | 25.5 | 16.3 | < 0.001 | 26.5 | 18.2 | < 0.001 |

| Negative impact of prolapse | 73.5 | 26.7 | 19.4 | 27.6 | < 0.001 | 16.2 | 24.8 | < 0.001 | 14.7 | 25.1 | < 0.001 |

| Role limitations | 58.5 | 29.2 | 15.8 | 24.9 | < 0.001 | 11.3 | 20.1 | < 0.001 | 11.6 | 21.4 | < 0.001 |

| Physical limitations | 55.0 | 30.2 | 16.6 | 26.0 | < 0.001 | 10.9 | 19.9 | < 0.001 | 11.1 | 21.0 | < 0.001 |

| Social limitations | 20.6 | 26.5 | 6.0 | 16.7 | < 0.001 | 3.9 | 12.8 | < 0.001 | 4.2 | 12.7 | < 0.001 |

| Personal relationships | 43.8 | 37.5 | 16.5 | 26.8 | < 0.001 | 11.0 | 22.2 | < 0.001 | 10.4 | 19.5 | < 0.001 |

| Emotions | 29.6 | 27.7 | 9.3 | 18.6 | < 0.001 | 6.5 | 15.9 | < 0.001 | 5.4 | 13.7 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep/energy | 32.4 | 22.4 | 18.5 | 18.5 | < 0.001 | 16.7 | 16.3 | < 0.001 | 17.7 | 17.9 | < 0.001 |

| Severity of symptoms | 40.8 | 19.8 | 17.1 | 16.4 | < 0.001 | 14.4 | 16.0 | < 0.001 | 13.5 | 15.5 | < 0.001 |

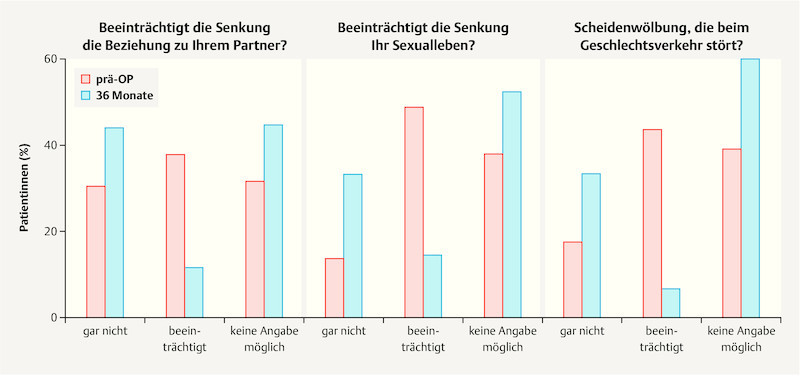

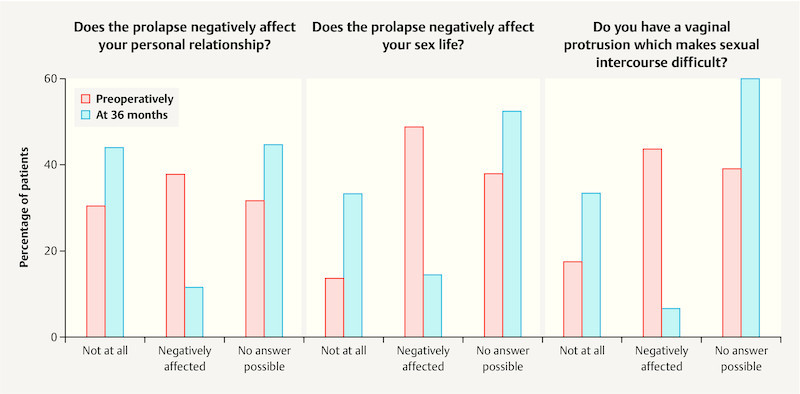

Sexuality and the relationship with their partner were assessed based on the evaluation of three questions of the P-QoL (Does the prolapse negatively affect your personal relationship?, Does the prolapse negatively affect your sex life?, Do you have a vaginal protrusion which makes sexual intercourse difficult?) ( Fig. 4 ). As regards the negative impact of the prolapse on the patientʼs personal relationship, the number of affected patients dropped from 37.9% (106/280) preoperatively to 11.4% (30/264) after 36 months (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test). Preoperatively, 31.8% (89/280) of patients answered the question with “no answer possible”; after 36 months the figure was 44.7% (118/264). Before undergoing surgery 48.6% (137/282) of patients stated that their sex life was negatively affected; after 36 months 14.4% (38/264) reported a negative impact on their sex life (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test). 37.9% (107/282) of patients stated preoperatively and 52.3% (138/264) of patients said at 36 months postoperatively that they could not provide any information about any limitations on their sex life. After surgery, significantly fewer patients reported that they had a vaginal protrusion which made sexual intercourse difficult (preoperatively: 43.5% (117/269); after 36 months: 6.6% (17/256); p < 0.001, Wilcoxon test; “no answer possible”: 39.0% (105/269) preoperatively and 60.2% (154/256) 36 months postoperatively) ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Improvement in sexual function after 36 months. Evaluation of the questions about the negative impact of prolapse on their personal relationship, the negative impact of prolapse on their sex life and whether the vaginal protrusion made sexual intercourse difficult. Available responses included: “not at all”, “negatively affected” and “no answer possible”. Responses were evaluated before the implantation and 6, 12 and 36 months after implantation.

Preoperatively 15.6% (45/289) of patients suffered from dyspareunia. At follow-up after 36 months postoperatively 6.4% (17/266) of surgically treated patients still experienced dyspareunia, with 4.5% (12/266) of patients suffering from de novo dyspareunia and 1.9% (5/266) from persisting dyspareunia.

Anatomical results

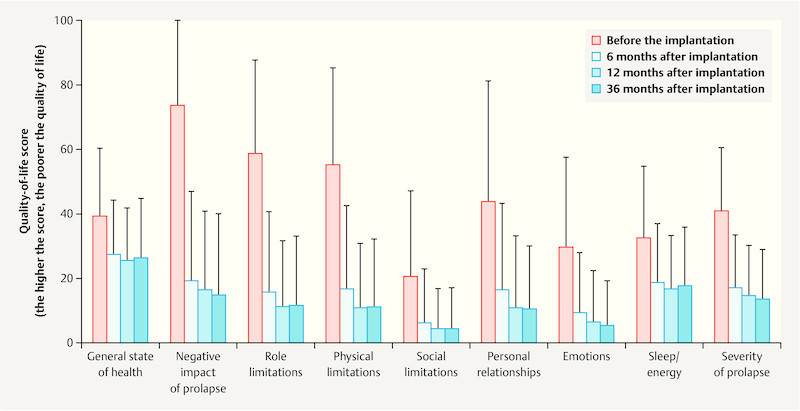

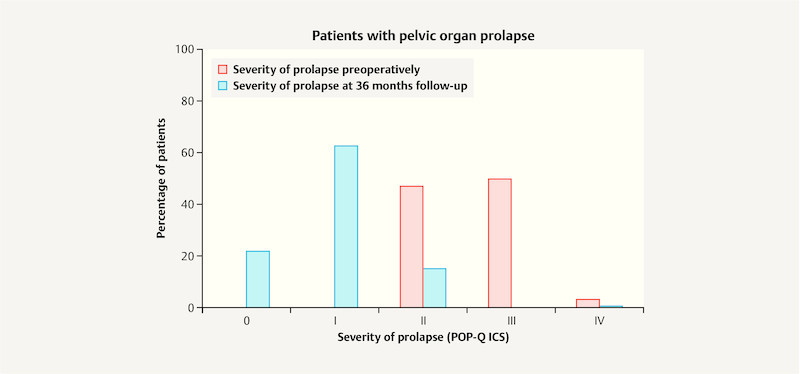

The severity of prolapse was determined preoperatively and postoperatively using the POP-Q system 17 . Grade II prolapse was diagnosed preoperatively in 47.1% (136/289) of patients; 49.8% (144/289) of patients had grade III prolapse, and 3.1% (9/289) of patients had grade IV prolapse. After 36 months 21.8% (55/252) of patients had no prolapse (grade 0); 62.7% (158/252) had grade I prolapse; grade II prolapse was diagnosed in 15.1% (38/252) of patients, and 0.4% (1/252) had grade IV prolapse ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Pelvic organ prolapse preoperatively and after 36 months. The bar chart shows the percentage of patients with grade 0, I, II, III or IV pelvic organ prolapse preoperatively and 36 months after implantation.

Of the patients who had surgery of the anterior compartment, 2.4% (7/286) had recurrence after 12 months and a further 1.9% (5/269) had recurrence after 36 months. Five patients also had prolapse of the posterior compartment, and two patients who initially experienced posterior prolapse also presented with anterior defects during a later examination. The anterior recurrences therefore occurred in combination with posterior defects.

By the time of the follow-up examination at 12 months after surgery, 10.1% (29/286) of patients had developed recurrent prolapse in the posterior compartment; at the time of the follow-up at 36 months postoperatively 3.7% (10/269) had developed recurrence. Recurrence in the apical compartment developed in 2.8% (8/286) of patients after 12 months, and in a further 1.9% (5/269) of patients after 36 months.

Posterior colporrhaphy was done in 34.9% (101/289) of patients; 25.6% (74/289) of patients underwent mesh-based repair of the posterior compartment. Some individual patients had several concomitant procedures. 42.9% (124/289) of patients did not have concomitant surgery of the posterior compartment. Concomitant posterior colporrhaphy reduced the risk of recurrence from 28% (no concomitant posterior reconstruction) to 11.1% (p < 0.004, χ 2 -test). Patients who had concomitant posterior plasty and mesh reinforcement had the lowest risk of recurrence (6.3%) (p < 0.001, χ 2 -test). The recurrence rate after 12 months across all compartments was 14.0% (40/286). In the period between 12 months and 36 months after surgery, 5.2% (14/269) of patients suffered repeat prolapse.

When patients reported their previous medical history, 31.8% (92/289) stated that they had already had a hysterectomy. A hysterectomy was carried out concomitantly with cystocele correction in 36.3% (105/289) of patients. Concomitant or existing hysterectomy increased the risk of recurrence in the posterior compartment 2.8-fold.

Adverse events

Adverse events were documented at every time point during the course of the study. The recorded adverse events were assessed by an independent CEC using the CTCAE codes. As described in previous publications, intraoperative and perioperative complications were rare 5 , 6 : bladder lesions occurred in 1.7% (5/289) of cases, and ureteral injury or bleeding requiring transfusion was reported in 0.3% (1/289) of cases, respectively. Urinary tract infection or infected hematoma were diagnosed in 0.3% (1/289) of cases, respectively, after discharge from hospital. In both cases the infection was treated conservatively. 0.3% (1/289) of patients experienced positional pain.

Twenty-two adverse events were recorded in 21 patients between the follow-up at 12 months and the follow-up at 36 months, although none of the events could be definitively associated with the mesh implant. However, 8 of the reported events were definitively linked to the surgical method: one patient suffered from pain in the area of the mesh and 7 patients had mesh erosion (first reports). The mesh implant of the patient experiencing pain was mobilized during an outpatient procedure, three patients with erosion were treated in an outpatient setting under local anesthesia, and no treatment was indicated in four patients with erosion. Patients who underwent hysterectomy concomitantly with cystocele correction had a 2.25-fold higher risk of developing erosion. Other recorded complications included urinary tract infection (n = 1), hematuria (n = 1), thrombosis and hernia (n = 1), fecal incontinence (n = 2), urinary incontinence (n = 3), pain (n = 4) and recurrence in the operated compartment (n = 5, cf. “Anatomical results”).

The previously published study data showed that at follow-up after 12 months 10.5% (30/286) of patients presented with erosion as measured against the primary study objective 5 , 6 . In 56.7% (17/30) of these erosions, medication or an outpatient procedure performed under local anesthesia were sufficient. 43.3% (13/30) of cases with erosion required surgical intervention under general anesthesia, although none of the patients required explantation of the mesh. 46.7% (14/30) of all erosions were described as asymptomatic.

Discussion

This long-term, prospective, multicenter study with 289 patients investigated the impact of implanting an alloplastic mesh for cystocele correction on patientsʼ quality of life and sexuality and the anatomical outcome. Well-known risks for all methods used for pelvic floor reconstruction include chronic pain, dyspareunia and recurrent prolapse 1 , 14 , 25 . These factors can significantly reduce the quality of life of affected patients even after surgery. Moreover, it was suspected that 1st generation alloplastic implants used since the early 2000s had a negative impact on patientsʼ quality of life, particularly on their sex life 16 . The continuous improvements in mesh implants and the increased experience of surgeons has led to a reduction in mesh-induced side-effects 1 .

According to current census and DRG data, the patient population of this study reflected a typical patient group 23 , 24 . These results therefore are an interesting contribution to the treatment of pelvic floor prolapse in a group of patients who are typically most affected by prolapse.

The patient survey about their quality of life showed a significant improvement for all investigated areas over the course of the study. Patients already had a significantly lower impairment of their quality of life at six months after surgery. At 12 and 36 months after the procedure, the quality of life of the surveyed study participants had improved even more, and the difference to the preoperative figures remained significant. Further studies have also confirmed that mesh-based correction of pelvic organ prolapse can significantly improve patientsʼ quality of life, despite mesh-associated side-effects 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 .

The evaluation of the questions on sexuality in the P-QoL questionnaire showed a significant improvement in sexual function after cystocele correction. Sexual function of patients with dyspareunia was severely affected preoperatively. The average rate for dyspareunia reported in the literature is 12% 31 . In our study, 15.6% of women had dyspareunia before undergoing surgery. After 6 and 12 months, 2.5 and 2.4% of patients, respectively, had dyspareunia 5 , 6 ; after 36 months only 1.9% of patients still suffered from dyspareunia. At follow-up after 36 months, de novo dyspareunia was only reported in 4.5% (12/266) of cases. However, it should be noted that the majority of patients reported that they were not sexually active. This could be due to advanced age, co-morbidities or lack of interest. Both the patients and their partners need to be considered here. The reports in the literature on sexual function after (mesh-based) surgery of the pelvic floor are inconsistent 15 , 32 , 33 , and further research into dyspareunia after different surgical procedures is urgently required.

Patients benefited from a highly significant improvement of their quality of life in all areas and the procedure-related risks are acceptable. The good anatomical results reported in this study can be explained by the lateral and apical adjustable fixation of the mesh implant in the middle compartment. In a retrospective cohort study, Yang and colleagues compared transobturator mesh implants (multipoint fixation) with a single incision procedure. The rate of recurrence at two years after surgery was the same for both methods. Mesh erosion was less common for the single incision method, but the rate of postoperative stress incontinence was lower with the transobturator fixation method 34 . There are few comparative studies, and further studies to differentiate between the results for the available mesh implantation methods are necessary. The results of our study confirm the low rate of recurrence after implantation of an alloplastic mesh for cystocele repair described in the AWMF guidelines compared to conventional anterior colporrhaphy, which has a recurrence rate of up to 30% 1 , 25 . In contrast, the recently published PROSPECT study found no benefit for mesh-based procedures compared to conventional methods 26 . They found no significant differences with regard to undesirable events, rates of dyspareunia and recurrence, and the number of repeat operations. However, the authors reported that a repeat operation for mesh-induced complications was necessary in 9% of women 26 . It should be noted that 75% of patients with erosion which required surgical removal of the visible aspect were asymptomatic. In our study, most erosions occurred in the period up to 12 months after surgery. An erosion relevant for the objective of the study was reported in 10.5% (30/286) of patients. Erosions were only found in 2.6% (7/269) of patients in the period between 12 and 36 months postoperatively. These results confirmed the early occurrence of erosion reported in the literature 35 . Patients who underwent hysterectomy concomitantly with cystocele correction had a 2.25-fold higher risk of developing erosion. This observation accords with the reports given in the literature 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 . It has been assumed that this is due to the larger wound area 37 . This study has also shown that previous or concomitantly performed hysterectomy increases the risk of rectocele almost threefold. It is known from the literature that hysterectomy increases the incidence of re-operation 40 . These associations require further observation and analysis to improve the assessment of therapy options in individual cases.

Twenty-two adverse events were reported between the follow-up at 12 months and the follow-up at 36 months. None of these were previously unknown events. The patient survey on quality of life showed that there was only limited improvement after 12 months. This indicates that future studies could be designed with shorter observation periods. Study results could then be applied earlier to improve the treatment options of affected patients. However, data on the long-term impact of alloplastic implants are lacking, and longer observation periods are therefore still necessary.

The choice of the appropriate surgical procedure to treat pelvic organ prolapse should be made after careful urogynecological examination and in accordance with the current guidelines 1 , 25 , 41 . Patients should additionally receive a detailed individual briefing about the different surgical procedures available with and without implantation of an alloplastic mesh, the different surgical approaches, and the respective benefits and drawbacks. It is important that the surgeon also considers his own surgical expertise when advising the patient.

The study design was limited to an examination of a single group of patients. An examination of the results and a comparison with other methods is only possible using the current literature. Moreover, the patient survey based on questions about their sexuality is limited as the statements were obtained from the P-QoL survey. An additional questionnaire for the evaluation of sexual function is planned for future studies.

Conclusion

This prospective multicenter examination into the use of a titanized mesh with distal, lateral and apical fixation found that the anatomical results were very stable and the rate of recurrence was very low (4.5%) for the operated anterior compartment. It was significantly lower than for conventional anterior plasty operations 1 . In terms of quality of life, highly significant improvements were recorded for all areas, including the much discussed area of personal relationships and sexuality. As with every surgical procedure, mesh-based pelvic floor reconstruction has its specific risks. These risks are acceptable if the surgeon is sufficiently experienced. The procedure can therefore be offered to patients when advising them about possible surgical options; it is suitable both to treat recurrence and in a primary setting for patients with high-grade prolapse who require long-term pelvic floor stability 25 , 41 .

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Lutz Sternfeld for his support during the conception and design of the study and Arim Shukri for his analysis of the statistical data. Our thanks also go to Dr. Angelika Greser and Dr. Elke Nolte for their critical review of the manuscript.

Danksagung

Wir danken Dr. Lutz Sternfeld für die Unterstützung bei der Konzeption und dem Studiendesign und Arim Shukri für die statistischen Datenanalysen. Bei Dr. Angelika Greser und Dr. Elke Nolte bedanken wir uns für die kritische Überprüfung des Manuskripts.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest beyond the activities listed below. The activities listed here had and have no effect on the results of the study or the studyʼs publication. Christian Fünfgeld: speakerʼs fees from pfm medical, Serag Wiessner, BARD, AMS, AMI, Astellas, Recordati, Promedon; Mathias Mengel: speakerʼs fees from pfm medical, AMI; Markus Grebe: speakerʼs fees from pfm medical; Dirk Watermann: speakerʼs fees for research from Serag Wiessner, fees from AMS and Johnson & Johnson; Margit Stehle, Brigit Henne, Jan Kaufhold: none./ Die Autoren versichern, dass über die nachfolgend genannten Interessenkonflikte hinaus keine weiteren Konflikte bestehen. Die aufgeführten Tätigkeiten hatten und haben keinen Einfluss auf die Studienergebnisse oder deren Publikation. Christian Fünfgeld: Vortragshonorare von pfm medical, Serag Wiessner, BARD, AMS, AMI, Astellas, Recordati, Promedon; Mathias Mengel: Vortragshonorare von pfm medical, AMI; Markus Grebe: Vortragshonorare von pfm medical; Dirk Watermann: Vortragshonorare für Forschung von Serag Wiessner, Honorare von AMS und Johnson & Johnson; Margit Stehle, Brigit Henne, Jan Kaufhold: keine.

References/Literatur

- 1.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG) Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Diagnostik und Therapie des weiblichen Descensus genitalis 2016. Online:http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-006l_S2e_Descensus_genitalis-Diagnostik-Therapie_2016-11.pdflast access: 15.08.2017

- 2.Slieker-ten Hove M C, Pool-Goudzwaard A L, Eijkemans M J. The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse symptoms and signs and their relation with bladder and bowel disorders in a general female population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1037–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0902-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mengel M, Henne B, Fünfgeld C. Entwicklung des Miktionsverhaltens unter Belastungsbedingungen und Lebensqualität nach netzgestützter Zystozelenkorrektur. Gynäkologische Praxis. 2015;39:10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber A M, Walters M D, Piedmonte M R. Sexual function and vaginal anatomy in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1610–1615. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fünfgeld C, Mengel M, Henne B. Zystozelenkorrektur mit alloplastischen Netzen. Frauenarzt. 2015;56:1068–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farthmann J, Fuenfgeld C, Mengel M. Improvement of pelvic floor-related quality of life and sexual function after vaginal mesh implantation for cystocele: primary endpoint of a prospective multicentre trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Fattah M, Akinbowale F, Schinee B. Primary and repeat surgical treatment for female pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in parous women in the UK: a register linkage study. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000206. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slieker-ten Hove M C, Pool-Goudzwaard A L, Eijkemans M JC. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:1840–1.84E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen A L, Smith V J, Clark A L. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Julian T M. The efficacy of Marlex mesh in the repair of severe, recurrent vaginal prolapse of the anterior midvaginal wall. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1472–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shull B L, Benn S J, Kuehl T J.Surgical management of prolapse of the anterior vaginal segment: an analysis of support defects, operative morbidity, and anatomic outcome Am J Obstet Gynecol 19941711429–1436.discussion 1436–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD003882. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003882.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denman M A, Gregory W T, Boyles S H. Reoperation 10 years after surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:5550–5.55E7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(02):CD012079. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barski D T, Otto T, Gerullis H. Systematic review and classification of complications after anterior, posterior, apical, and total vaginal mesh implantation for prolapse repair. Surg Technol Int. 2014;24:217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UPDATE on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: FDA Safety Communication 2011. Online:http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htmlast access: 15.08.2017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bump R C, Mattiasson A, Bo K. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Digesu G A, Khullar V, Cardozo L. P-QOL: a validated questionnaire to assess the symptoms and quality of life of women with urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:176–181. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenz F, Stammer H, Brocker K. Validation of a German version of the P-QOL Questionnaire. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:641–649. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0809-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schar G, Kolbl H, Voigt R. [Recommendations by the Urogynecology Working Group for sonography of the lower urinary tract within the scope of urogynecologic functional diagnosis] Ultraschall Med. 1996;17:38–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1003144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Cancer Institute . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/National Institutes of Health; 2010. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) 4.03. N.C. Institute, ed. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz K F, Altman D G, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistisches Bundesamt Results of Microcensus 2013 2013. Online:https://www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/SocietyState/Health/HealthStatusBehaviourRelevantHealth/Tables/BodyMassIndex.htmlLast access: 19.06.2017

- 24.Institut für das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus G-DRG V2013 Browser 2012 § 21 KHEntgG 2013. Online:http://www.g-drg.de/content/view/full/4887last access: 19.06.2017

- 25.Chapple C R, Cruz F, Deffieux X. Consensus statement of the European Urology Association and the European Urogynaecological Association on the use of implanted materials for treating pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glazener C M, Breeman S, Elders A. Mesh, graft, or standard repair for women having primary transvaginal anterior or posterior compartment prolapse surgery: two parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled trials (PROSPECT) Lancet. 2017;389:381–392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Haddad R, Svabik K, Masata J. Womenʼs quality of life and sexual function after transvaginal anterior repair with mesh insertion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;167:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yesil A, Watermann D, Farthmann J.Mesh implantation for pelvic organ prolapse improves quality of life Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014289817–821.doi:10.1007/s00404-013-3052-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomin A, Touboul C, Hequet D. Genital prolapse repair with Avaulta Plus mesh: functional results and quality of life. Prog Urol. 2013;23:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hefni M, Barry J A, Koukoura O. Long-term quality of life and patient satisfaction following anterior vaginal mesh repair for cystocele. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287:441–446. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2583-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(04):CD004014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zyczynski H M, Rickey L, Dyer K Y. Sexual activity and function in women more than 2 years after midurethral sling placement. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:4210–4.21E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers R G, Kammerer-Doak D, Darrow A. Does sexual function change after surgery for stress urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse? A multicenter prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang T H, Wu L Y, Chuang F C. Comparing the midterm outcome of single incision vaginal mesh and transobturator vaginal mesh in treating severe pelvic organ prolapse. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Khawand D, Wehbe S A, OʼHare P G. Risk factors for vaginal mesh exposure after mesh-augmented anterior repair: a retrospective cohort study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:305–309. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold K P, Ward R M, Zimmerman C W. Factors associated with exposure of transvaginally placed polypropylene mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1461–1466. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farthmann J, Watermann D, Niesel A. Lower exposure rates of partially absorbable mesh compared to nonabsorbable mesh for cystocele treatment: 3-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iyer S, Botros S M. Transvaginal mesh: a historical review and update of the current state of affairs in the United States. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:527–535. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caliskan E, Özdamar Ö. Should uterus be removed at pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a reappraisal of the current propensity. Pelviperineology. 2017;36:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridgeway B, Chen C C, Paraiso M F. The use of synthetic mesh in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:136–152. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318161e6c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly-Identified Health Risks SCENIHR Opinion on the safety of surgical meshes used in urogynecological surgery 2015Online:https://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/emerging/docs/scenihr_o_049.pdflast access: 19.06.2017