Highlights

-

•

Gallstone sigmoid ileus is a rare condition caused by a stone obstructing the sigmoid colon.

-

•

Manual evacuation of an obstructing gallstone has not previously been documented before.

-

•

No center has reported more than one case; consequently no case series are documented in the literature.

-

•

Where conservative measures fail, endoscopy/lithotripsy appear valuable next line interventions.

-

•

Gallstone ileus can progress to gallstone sigmoid ileus.

Keywords: Gallstone sigmoid ileus, Cholelithiasis, Large bowel obstruction, Minimally invasive surgery, Lithotripsy, Endoscopy

Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Gallstone sigmoid ileus is a rare condition that presents with symptoms of large bowel obstruction secondary to a gallstone impacted within the sigmoid colon. This arises because of three primary factors: cholelithiasis causing a cholecystoenteric fistula; a gallstone large enough to obstruct the bowel lumen; and narrowing of the bowel.

We describe 3 patients treated in a district general hospital over a 3-year period, and discuss their management.

Methods

Cases were retrospectively analysed from a single center between 2015 and 2017 in line with the SCARE guidelines.

Results

3 patients – 2 female, 1 male. Age: 89, 68, 69 years. 2 cholecystocolonic fistulae, 1 cholecystoenteric (small bowel) fistula.

Patient 1: Unsuccessful endoscopic attempts to retrieve the (5 × 5 cm) gallstone resulted in surgery. Retrograde milking of the stone to caecum enabled removal via modified appendicectomy.

Patient 2: Endoscopy and lithotripsy failed to fragment stone. Prior to laparotomy the stone was palpated in the proximal rectum enabling manual extraction.

Patient 3: Laparotomy for gallstone ileus failed to identify a stone within the small bowel. Gallstone sigmoid ileus then developed. Conservative measures successfully decompressed the large bowel 6 days post-operation.

Conclusions

This is the first case series highlighting the differing strategies and challenges faced by clinicians managing gallstone sigmoid ileus. Conservative measures (including manual evacuation), endoscopy, lithotripsy and surgery all play important roles in relieving large bowel obstruction. It is essential to tailor care to individual patients’ needs given the complexities of this potentially life threatening condition.

1. Introduction

Gallstone sigmoid ileus is a rare condition that presents with symptoms of large bowel obstruction. The name is somewhat of a misnomer given that the condition relates to colon rather than small bowel. Gallstone sigmoid ileus arises as a result of three primary factors; cholelithiasis causing a cholecystoenteric fistula, a gallstone wide enough to obstruct a large bowel lumen and narrowing of the bowel.

Two mechanisms exist by which a gallstone can pass into the large bowel and obstruct the lumen, cholecystocolonic and cholecystoenteric fistulas. The cholecystocolonic route represents the more common pathway for gallstone sigmoid ileus to arise. The other being that the gallstone transits the small bowel via the ileocaecal valve before becoming lodged in the sigmoid colon.

Given the rarity of such presentations there is no guidance available to direct clinical management. Strategies to relive luminal obstruction vary extensively from conservative measures to endoscopy/lithotripsy to surgery. Management strategies appear to be tailored to the individual’s condition and center’s expertise.

We present 3 patients from a district general hospital within a 3-year period treated for gallstone sigmoid ileus. These cases add to literature by emphasizing the need for diagnostic awareness in patients with large bowel obstruction and highlighting what may be an under reported condition.

2. Methodology

Three patient presentations were analysed and reported inline with SCARE guidelines [1] from a single center.

3. Results

3.1. Patient 1

An 89-year-old woman presented as an emergency with an 8-day history of vomiting, abdominal pain and constipation [2]. Comorbidities included diverticulosis, hypothyroidism and hypertension.

Clinical findings elicited localised guarding in the left lower quadrant with a distended tympanic abdomen. Abdominal x-ray revealed dilated loops of both large and small bowel. A computerized tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1) showed cholecystitis; a cholecystocolonic fistula between gallbladder and hepatic flexure of colon; widespread diverticulosis and a high attenuation mass (representing a gallstone) in the proximal sigmoid colon.

Fig. 1.

Coronal CT image of abdomen demonstrating a hyperechoic mass in the sigmoid colon.

Two consultants initially attempted non-surgical management with flexible sigmoidoscopy. This proved unsuccessful in dislodging the stone owing to poor visibility, stone size and diverticular disease. Given the risk of iatrogenic perforation to the bowel, surgery was required.

The patient underwent a lower midline laparotomy during which the gallstone was found impacted within a diverticular segment of sigmoid colon. The cholecystocolonic fistula was identified but left alone. Attempts to pass the stone distally via the rectum were unsuccessful. The gallstone was milked back to the caecum. Appendicectomy was performed, with the appendiceal opening dilated enough to allow the gallstone to be extracted and the colon decompressed. The Aappendix base was closed with a linear stapling device and the staple line oversewn. The gallstone measured 5 × 5 cm. The patient recovered well and discharged six days post surgery.

3.2. Patient 2

A 69-year-old woman presented with a 7-day history of vomiting and absolute constipation for 24 h. The patient had undergone attempted laparoscopic cholecystectomy 2 months earlier. Surgery was abandoned because the gallbladder was covered by omentum and surrounded by dense adhesions.

Colonoscopy earlier in the year was normal, demonstrating no evidence of a cholecystocolonic fistula or diverticular disease. Past medical history included a hysterectomy 10yrs prior, bilateral knee replacements for osteoarthritis and cholelithiasis.

On examination the patient’s abdomen was tender in the left lower quadrant. Bloods on admission demonstrated raised inflammatory markers; white blood cell count (WBC) of 12.2 and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) of 156. Intravenous fluids and antibiotics were commenced for suspected diverticulitis.

CT (Fig. 2) demonstrated a large calcified gallstone (maximum diameter 4.8 cm) in the distal sigmoid colon, with mural thickening, oedema, and inflammatory stranding of the mesenteric fat. Bowel obstruction down to this level was noted, with a maximal caecal caliber of 9.1 cm.

Fig. 2.

Gallstone impacted within the sigmoid colon.

Symptoms failed to resolve spontaneously. Non-operative measures were attempted. The patient underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy (performed by two consultants). The stone was identified and found impacted within the sigmoid colon. Attempts to endoscopically grasp and withdraw the stone failed. Endoscopic lithotripsy was then performed but this proved ineffective at fracturing the gallstone. On 3 occasions the lithotripter broke, ultimately resulting in the procedure being abandoned.

2 days later the patient’s symptoms had not improved. Repeat CT (Fig. 3) one week after the initial presentation still demonstrated sigmoid gallstone ileus with only partial resolution of the bowel dilatation.

Fig. 3.

Gallstone remains impacted within the sigmoid colon.

Due to the ongoing ileus the patient became unstable and was booked for a laparotomy and a Hartmann’s procedure. Under anesthesia proctoscopy was performed prior to the laparotomy. The large stone was manually palpated within the proximal rectum and subsequently removed via manual evacuation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Large gallstone following manual evacuation.

The patient returned to the ward post procedure and was discharged 48-h later. A decision not to operate on the cholecystocolonic fistula was made in view of the problematic laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

3.3. Patient 3

A 68-year-old man presented with a 3-day history of vomiting, colicky pain and absolute constipation. Abdominal x-ray demonstrated dilated loops of small bowel. Bloods on admission showed raised inflammatory markers (WBC 12.1, neutrophils 10.2, CRP 84.7).

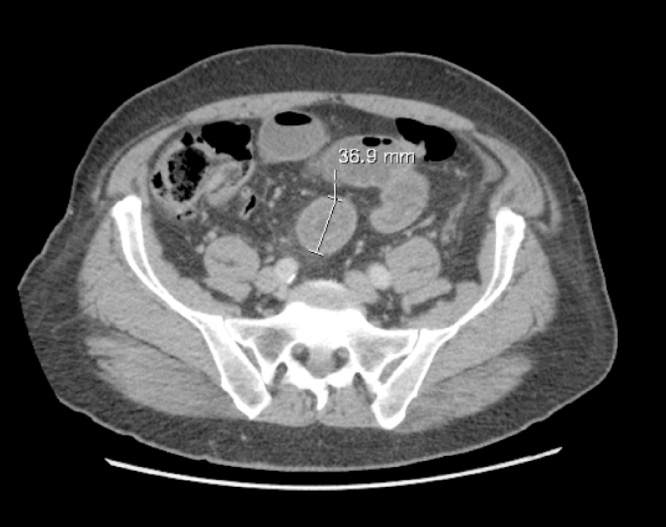

CT (Fig. 5) revealed a cholecystoenteric fistula between gallbladder and duodenum, extensive diverticular disease and a 3.6 cm diameter gallstone impacted within the distal ileum.

Fig. 5.

Axial CT image – 3.6 cm gallstone impacted within distal ileum.

The patient underwent a midline laparotomy, which failed to identify the gallstone in the small bowel. It was thought that the stone had moved beyond the ileocaecal junction into the large bowel. There was no evidence that it had passed.

Sequential abdominal x-rays (Fig. 6) post laparotomy repeatedly demonstrated dilated loops of large and small bowel. Conservative treatment with laxatives and gastrograffin was implemented. The patient’s observations and condition remained stable throughout.

Fig. 6.

Abdominal X-Ray 5 days post laparotomy.

A large gallstone was expressed spontaneously per rectum 6 days post procedure and the patient was discharged home the following day. The patient was reviewed 8-weeks following discharge and had made a full recovery. No further surgery with regard to the fistula was planned.

4. Discussion

All patients were aged 68 or older, and 2 were female. Increasing age and female sex are known aetiological risk factors for gallstone disease[3]. These factors correlate with other reported cases of gallstone sigmoid ileus [4], [5], [6], [7].

The literature highlights that patients developing gallstone sigmoid ileus have pre-existing luminal narrowing, most commonly secondary to diverticular disease. However patient 2 underwent colonoscopy 4 months before presentation with no evidence of diverticulosis or stricturing. We hypothesize that the gallstone became impacted within the sigmoid colon due to its size and angulation. Subsequent colonic inflammation likely narrowed the lumen, preventing stone passage.

We adopted conservative management in Patient 3,where the gallstone was not identified intraoperatively, in the expectation that the stone would pass spontaneously soon after, but with a low threshold for further surgery.

Non-surgical management strategies such as lithotripsy and endoscopic snare/basket retrieval have yielded varying results. Several authors describe successful resolution of large bowel obstruction with lithotripsy [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13].

Endoscopic extraction avoids the potential morbidity associated with open or laparoscopic surgery. The most significant risk of endoscopy is bowel perforation. Colonic perforation necessitating a Hartmann’s procedure following failed endoscopy has been reported [14].

Endoscopic extraction and lithotripsy were attempted, unsuccessfully, in 2 of our patients. For patient 2 we hypothesize that intubation with the mechanical lithotripter sufficiently dilated the inflammatory stricture, enabling the stone to transit into the rectum.

Other authors report spontaneous passage of a gallstone following attempted endoscopy [15], [16]. Manual evacuation was necessary to extract the obstructing gallstone in Patient 2. This has not previously been reported. On table proctoscopy before laparotomy may prevent unnecessary surgery.

Gallstone ileus can progress to sigmoid gallstone ileus, as in Patient 3. Vaughan-Shaw describes a 70-year-old female with gallstone ileus secondary to 2 calculi in the jejunum. After successful initial management with enterolithotomy the patient represented 4 months later, again requiring surgery [5]. Halleran describes a 3.5 cm stone traversing the ileocaecal junction before obstructing the sigmoid colon [14].

Addressing each patient’s changing clinical state appears vital. We used surgery only after unsuccessful conservative management. Additional operative management of the cholecystoenteric/colonic fistulae was not undertaken in our patients (with comorbidities and surgical complexities highlighted. Patient follow-up (3–24 months) has identified no complications.

5. Conclusion

Our center has encountered three separate cases of sigmoid gallstone ileus within the last three years, with each case managed uniquely to meet each patient’s needs. Given that no other center has reported more than an individual case, our experience represents an up-to-date insight into the challenges and management strategies available to clinicians confronted by this rare condition.

The series highlights a number of unique aspects relating to gallstone sigmoid ileus. No previous case has utilised manual evacuation as a successful treatment. There have been no other cases where a negative laparotomy for small bowel obstruction has then resulted in large bowel obstruction secondary to a gallstone. Given that 3 patients have encountered this condition within 3 years highlights that in an ageing population gallstone sigmoid ileus may be more common than previously thought.

There is currently no pathway to help guide the management of gallstone sigmoid ileus; conservative management, endoscopy, lithotripsy and surgery all appear to have a valuable place in the arsenal available to clinicians. All methods of stone extraction need to be considered prior to any intervention. Assessing the rectum under anaesthesia (as in Patient 2) appears a sensible adjunct prior to surgery. Utilizing less invasive measures where possible avoids the potential morbidity of surgery. However, surgery remains an important tool in managing non-resolving sigmoid ileus and in the emergency setting.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

NF – data collection, data analysis, writing paper

RK – data analysis, writing paper

TL – data analysis, writing paper

JR – data collection

SF – study concept, data analysis, consultant in charge of patient care − input regarding patient 2

AZ – study concept, data analysis, consultant in charge of patient care − input regarding patient 3

NW – study concept, data analysis, consultant in charge of patient care − input regarding patient 1.

Guarantor

Nicholas Farkas, Ravindran Karthigan, Nicholas West.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., Afifi R., Al-Ahmadi R., Albrecht J., Alsawadi A., Aronson J., Ather M.H., Bashashati M., Basu S., Bradley P., Chalkoo M., Challacombe B., Cross T., Derbyshire L., Farooq N., Hoffman J., Kadioglu H., Kasivisvanathan V., Kirshtein B., Klappenbach R., Laskin D., Miguel D., Milburn J., Mousavi S.R., Muensterer O., Ngu J., Nixon I., Noureldin A., Perakath B., Raison N., Raveendran K., Sullivan T., Thoma A., Thorat M., Valmasoni M., Massarut S., D’cruz A., Baskaran V., Giordano S., Roy G., Machado-Aranda D., Healy D., Carroll B., Rosin D. The SCARE Statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2017;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cargill A., Farkas N., Black J., West N. A novel surgical approach for treatment of sigmoid gallstone ileus. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-209229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaffer E.A. Epidemiology and risk factors for gallstone disease: has the paradigm changed in the 21 st century? Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2005;7:132–140. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.P. Patel, T. Raiyani, D. Nunley-Gorman, Deadly Gallstone!, in: Am. J. Gastroenterol., NATURE PUBLISHING GROUP 75 VARICK ST, 9TH FLR, NEW YORK, NY 10013-1917 USA, 2012: pp. S320–S320.

- 5.Vaughan-Shaw P.G., Talwar A. Gallstone ileus and fatal gallstone coleus: the importance of the second stone. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008008. (bcr2012008008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventham N.T., Eves T., Raje D., Willson P. Sigmoid gallstone ileus: a rare cause of large bowel obstruction. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2010.2886. (bcr0420102886) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaney R.M. Colonic gallstone ileus: the rolling stones. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkhusheh M., Tonsi A.F., Reiss S., Owen E.R.T.C., Reddy K. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy for gallstone large bowel obstruction. Int. J. Case Rep. Images. 2011;2:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiss G., Gopi R., Ramrakhiani S. Unusual cause of colonic obstruction: gallstone impaction requiring mechanical lithotripsy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009;7:A20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterland P., Khan F.S., Durkin D. Large bowel obstruction due to gallstones: an endoscopic problem? BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201652. (bcr2013201652) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zielinski M.D., Ferreira L.E., Baron T.H. Successful endoscopic treatment of colonic gallstone ileus using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG. 2010;16:1533. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butruk E. Sigmoid laser lithotripsy for gallstone ileus. Folia Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;4:30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balzarini M., Broglia L., Comi G., Calcara C. Large bowel obstruction due to a big gallstone successfully treated with endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy. Case Rep. Gastrointest. Med. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/798746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halleran D.R., Halleran D.R. Colonic perforation by a large gallstone: a rare case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014;5:1295–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anagnostopoulos G.K., Sakorafas G., Kolettis T., Kotsifopoulos N., Kassaras G. A case of gallstone ileus with an unusual impaction site and spontaneous evacuation. J. Postgrad. Med. 2004;50:55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maltz C., Zimmerman J.S., Purow D.B. Gallstone impaction in the colon as a result of a biliary-colonic fistula. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53:776. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]