Abstract

MoodSwings 2.0 is a self-guided online intervention for bipolar disorder. The intervention incorporates technological improvements on an earlier validated version of the intervention (MoodSwings 1.0). The previous MoodSwings trial provides this study with a unique opportunity to progress previous work, whilst being able to take into consideration lesson learnt, and technological enhancements. The structure and technology of MoodSwings 2.0 are described and the relevance to other online health interventions is highlighted. An international team from Australia and the US updated and improved the programs content pursuant to changes in DSM-5, added multimedia components and included larger numbers of participants in the group discussion boards. Greater methodological rigour in this trial includes an attention control condition, quarterly telephone assessments, and red flag alerts for significant clinical change. This paper outlines these improvements, including additional security and safety measures. A 3 arm RCT is currently evaluating the enhanced program to assess the efficacy of MS 2.0; the primary outcome is change in depressive and manic symptoms. To our knowledge this is the first randomised controlled online bipolar study with a discussion board attention control and meets the key methodological criteria for online interventions

1. Introduction

Pharmacotherapy remains the foundation of treatment approach for bipolar disorder (BD). High relapse rates, and the recognition of the impact of psychosocial factors on illness episodes have seen the emergence of adjunctive psychotherapy as part of the treatment framework [1]. There is strong evidence for these interventions in improving relapse, symptoms and quality of life [1] Despite their utility, the real world application of these approaches is limited by assess issues including geography, program availability, time and cost [2, 3] It flags the need for easier access to specialist resources.

Evidence supporting the use of online interventions in the treatment of mental illness has grown [4]. Adding to this body of work are the outcomes for several online bipolar studies [5–9]. These studies have taken diverse approaches in applying psychoeducation [7, 8] and CBT principles [5, 6, 9] They target varied primary outcomes such as relapse [5, 6], mood symptoms [6, 7], quality of life [8, 9], and wellbeing [9]. Early findings are encouraging with evidence supporting improvement on quality of life [8], symptomatology [6, 7, 9], and wellbeing [9]. No study as yet has shown improvement on relapse. Limitations of this body of work include the use of attention control conditions that contain therapeutic elements [5, 7], modest sample sizes [6, 8, 9], the use of online tools for diagnosis [9], or a control that relies on treatment as usual as the comparator [8, 9].

The MoodSwings 1.0 program was one of the first bipolar online studies that targeted symptom severity and relapse as primary outcomes [6]. The head-to-head randomised trial compared two versions of the MoodSwings 1.0 program. Psychoeducation, plus interactive CBT features (referred to as MoodSwings Plus) was compared with psychoeducation only (referred to as MoodSwings), where the interactive CBT features were disabled [6]. A between treatment group difference in favour of MoodSwings Plus was found on mania symptoms at 12 months. Within treatment group improvements were found in both study arms, with the MoodSwings Plus group showing an impact on more of the study variables including symptom improvements, functionality, quality of life, social support and medication adherence [6]. Without a comparator control condition, this study was unable to provide an indication of any potential improvement of either MoodSwings version. The lack of a significant difference in relapse rates in this trial, may have been influenced by the limited by a modest sample size (n=156), high attrition and limited engagement in the online discussion boards [6].

Despite these limitations, the results of MoodSwing 1.0 were encouraging and qualitative feedback from participants was supportive of the program. An upgrade of the site, now known as MoodSwing 2.0 and its evaluation with a larger sample, using an attention control condition is currently being conducted. This is a critical element given recent evidence that waitlist controls are an unsuitable comparison as they markedly inflate effect sizes and may actually be a nocebo condition. [10]. This paper introduces MoodSwings 2.0 and the protocol of the current randomised controlled trial (RCT) aiming to assess its efficacy. It highlights the technological improvements, and notes additional security and safety measures that have relevance to all online health interventions.

2. Design and methods

2.1 Overview of design

This study is an international collaboration, with research sites at the University of Melbourne in Australia, and Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo Alto, California. It uses a 3-arm randomized controlled trial involving a parallel group stepped design. The 3 arms involve a moderated peer discussion board only (level one), discussion board plus psychoeducation (level two) or discussion board, psychoeducation and online interactive psychosocial tools (level three).

The primary aims of the study are to investigate whether the MoodSwings intervention results in decreased mood symptoms of both depression and mania/hypomania and to determine the differential efficacy of the different treatment arms. In addition, the impact of the program on relapse of illness, functionality, social support, quality of life, medication adherence and treatment satisfaction will be evaluated. It is hypothesised that Level III (discussion board, psychoeducation, and psychosocial tools) will be superior in comparison to both Level II (discussion board + psychoeducation) and Level I intervention (discussion board only), which acts as an attention control group.

2.2 Participants and recruitment methods

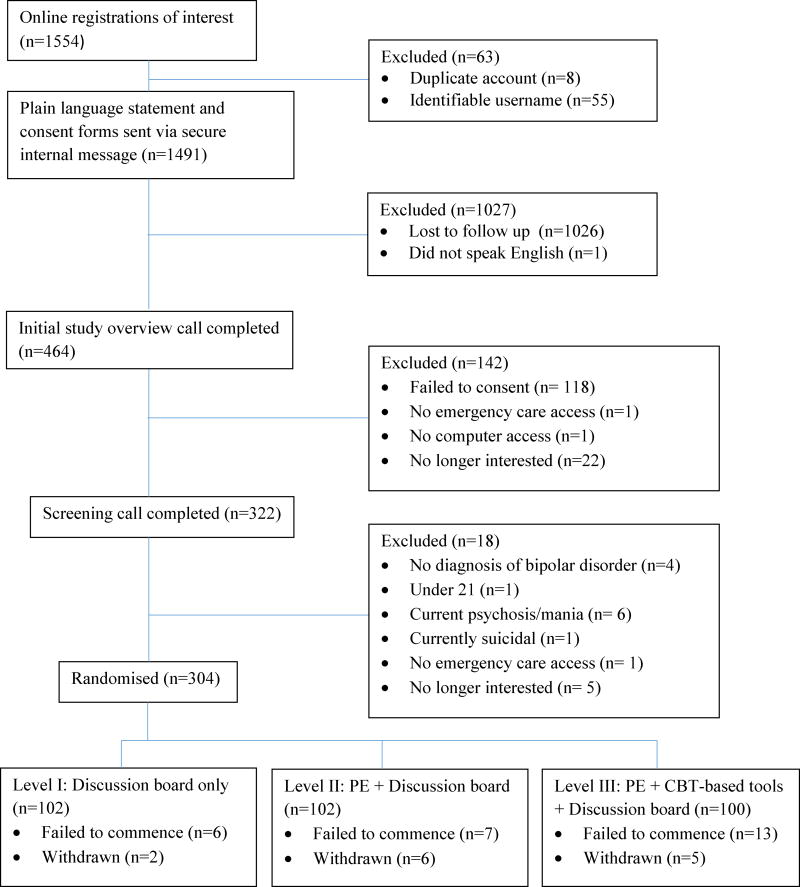

An international recruitment strategy was implemented in order to reach the target of 300 participants (150 per research site). Participants with a diagnosis of BD were recruited by posting on relevant websites and Facebook pages, such as the International Bipolar Foundation, DBSA CREST.BD, and Mental Health Awareness Australia. Existing waiting lists generated from other research projects, including MoodSwings 1.0, were contacted. Utilizing these approaches recruitment of 304 participants was reached in 13 months. Participant flow to date is presented in an interim consort diagram in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Recruitment Consort Flowchart

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation were as follows:

- Inclusion criteria:

- Meeting SCID criteria for BD I, II or NOS

- Aged between 21 – 65

- An absence of active suicidality, acute psychosis or mania at screening assessment. Those who fail this screening are eligible once symptoms are no longer acute

- Have received care (either routine or otherwise) for BD twice within the past 12 months

- Can read and speak English

- Access to emergency care

- Willing to provide emergency contact details

- Exclusion criteria:

- Current mania

- Current psychosis

In contrast to face-to-face multi-site trials where responsibility for participants is already defined via existing geographic boundaries, an online international study of this nature did not have pre-determined boundaries. To handle international participant assessments and recruitment responsibilities, the USA and Australian teams took responsibility for participants different geographic areas that were designated by ranking countries according to English speaking population numbers. The USA was responsible for North America, U.K., and Africa and the Australian team responsible for Australasia, Europe (excluding the U.K.) and South America.

2.3 Data Safety Monitoring Board DSMB

To ensure safety of participants, and the validity and integrity of data a DSMB has been established for this trial. This DSMB consists of four voluntary external consultants; three psychiatrists based in the US and a senior pharmacist based at the AUS site, all of who are independent of the trial. The DSMB undertakes a monitoring function, reviews procedures and decisions and advises on scientific and ethical issues regarding the study. In addition the DSMB monitors protocol breaches, oversees the confidentiality of data, quality of data collection, management and analysis. The DSMB also has a reporting responsibility to the NIH and each study sites IRB and ethics committee. Meetings of the DSMB via teleconferencing were scheduled throughout the trial, with additional meetings held as required.

2.4 Assessment Measures

A mixture of online and telephone assessments are used to provide greater methodological rigor than relying on self-report assessments alone. Table 1 outlines assessment time points and modality. All quarterly phone interviews are conducted with an independent rater blind to intervention level assignment.

Table 1.

Schedule of Assessments

| Screening | Baseline | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phone Assessment | ||||||

| SCID mood modules [11] | X | |||||

| SCID Psychosis module [11] | X | |||||

| HAM-D Item 3 [12] | X | |||||

| Cornell Service Index [13] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Young Mania Rating Scale [14] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale for Depression [15] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Time to Intervention (Relapse) [16] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Self-report online assessment | ||||||

| Demographics | X | |||||

| SF-12 (version 2) [17] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) [18] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Medical Outcomes Study - Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) [19] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) [20] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences [21] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) [22] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Motivation for Treatment (MTQ-8) [23] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Treatment Credibility Scale (modified) [24] | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Mood Symptom Tracking (online) | ||||||

| Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale for Depression – Self Report [25] | Completed every 4-weeks over the duration of the trial as part of the red flag protocol with feedback given directly to participants regarding mood symptom results | |||||

| Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale [26] | ||||||

| HAM-D (item 3) [12] | ||||||

Screening Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Research Version [SCID-5-RV; [11] mood modules is used to confirm bipolar diagnosis of bipolar I, II, or NOS via telephone interview. This is in line with previous online studies confirming diagnosis through a telephone clinical interview [27]. The Psychotic screen on this measure is used to exclude those currently with symptoms of psychosis. Suicidality is assessed by item 3 of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D; [12]. Participants scoring ≥ 3 are referred back to their service provider and excluded until their suicidal risk is reduced.

Baseline demographics and computer competency

Demographic details

These include gender, age, education, occupation, marital status, country of residence, ethnicity, living arrangements, current medications, clinical course, history of illness and treatment.

Computer and Internet Competency Assessment

This single item self-report scale was created for the MoodSwings 2.0 trial to provide a measure of participants use and comfort with the internet and social media. It lists 15 types of online activities, such as checking emails, online gaming and social networking. Participants check all the types of online activities they engage in.

Primary Outcomes

Mood Symptomatology

Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS; [14]

The YMRS is an 11-item scale, completed by the clinician to assess symptoms of mania. As this is rated on the telephone in this study, questions that traditionally require visual appraisal are asked directly. For example “how well do you keep up your appearance and grooming?”

Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale for Depression: [MADRS; [15]

The MADRS is a 10-item scale, completed by the clinician to assess symptoms of depression. It is sensitive to changes in depression over time.

Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

Relapse

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM 5 Research Version [SCID-5-RV; [11]

is conducted at each quarterly assessment to determine illness episodes.

Time to relapse [TIME; [16]

This measure assesses relapse or time to intervention, with intervention defined as initiation, discontinuation, or dose adjustment of a treatment, initiation of psychotherapy or ECT, visit to an emergency provider or hospitalization in response to new mood symptoms.

Service Utilisation

Cornell Service Index [CSI; [13]

The CSI is a brief assessment of health service use. It has good inter-rater and test-retest reliability and assesses four types of services: outpatient psychiatric or psychological services (e.g., psychotropic medication visits or psychotherapy), outpatient medical services (e.g., visits to medical providers), professional support services (e.g., home health nurse visits, meal delivery), and intensive services (e.g., emergency department visits or hospitalization).

Functionality

SF-12 (version 2): [SF-12; [17]

This scale is a short, multipurpose measure of perceived impairment due to health problems.

Quality of Life

Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: [Q-LES-Q; [18]

This measure assesses subjective quality of life (i.e. physical health, subjective feelings, leisure activities and social relationships).

Social Support

Medical Outcomes Study - Social Support Survey: [MOSS-SS; [19]

This social support scale was specifically designed for use with chronic disease populations. It consists of 4 subscales referring to different elements of perceived social support. These include emotional/informational support, tangible support, affectionate support, and positive social interaction.

Medication Adherence

Medication Adherence Rating Scale: [MARS; [20]

The MARS is a valid measure of medication adherence with significant correlations with other measures of medication adherence (p<.01) and with serum blood levels at p<.05 [20]

Stigma

Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences [ISE; [21]

This scale of stigmatising experiences consists of two subscales: Stigma Experiences Scale (measuring frequency and prevalence) and Stigma Impact Scale (measuring the intensity of psychosocial impact).

Treatment Related Assessments

Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire 18: [PSQ-18; [22]

This scale assesses overall satisfaction with current medical care.

Motivation for Treatment. [MTQ-8; [23]

This is an eight item scale assessing motivational reasons to seek treatment. All items were based on the Circumstances, Motivation, Readiness, and Suitability scales for substance abuse treatment.

Treatment Credibility Scale [24] - Modified

For the purposes of this study the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire was modified to specifically apply to bipolar disorder and the MoodSwings 2.0 program. This was done in a similar manner to Klein et. al who revised this questionnaire to suit their anxiety programs [28].

Incentive payments

Participants who complete each set of quarterly phone and online assessments will accrue an incentive payment of a $40.00 US gift card per assessment package (i.e. participants must complete both the online assessment and the phone assessment). These incentives will be sent to the participant via email or postal mail at the conclusion of the study period.

Use of MoodSwings – Activity Tracking

The MoodSwings 2.0 website is also setup to automatically track participant activity on the site. This includes: Individual page visits, log in and log out times, internal messages sent and received by the participant, interactions on the discussion forums, use of the interactive tools, and a calculation of total time spent on the site. The site is set up to time out after 15 minutes of inactivity, requiring the participant to log back in, providing some accuracy of time on site calculations. This information provides not only usage details regarding most popular pages, but allows for the calculation of dose effects.

The MoodSwings Program

MoodSwings is a 5 module program delivered over 10 weeks (one module released every 2 weeks), followed by a series of 3 booster modules delivered monthly. Table 2 provides an outline of these modules, the content and changes made in MoodSwings 2.0 (a detailed description of the MoodSwings program has been reported in Lauder et al., 2012 [29]).

Table 2. Summary of the MoodSwings program and Enhancements made in MoodSwings 2.0.

Summary of the MoodSwings program and content changes

| MoodSwings content | Content changes as part of MoodSwings upgrade |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Modules | 1. What is bipolar disorder? | Reviews symptoms and criteria for diagnosis | Each module now contains video vignettes using consumer consultant related. Material is directly linked to module content | |

| 2. Stress and triggers | Outlines common stressors and triggers, and offers information about mood monitoring and stress reduction. | Upgrading of interactive mood monitor. Sleep data is now graphed along with mood, anxiety and irritability Relaxation audio included in module | ||

| 3. Medication | Covers the biological basis for bipolar disorder and the role of medication. | |||

| 4. Depression | Covers symptoms and warning signs of depression, as well as information about helpful strategies. | |||

| 5. Elevated mood | Covers symptoms and warning signs of hypomania and mania, as well as information about helpful strategies. | Previously separate elevated mood modules or mania and hypomania are now combined | ||

| Booster Modules | 3 months | Reviews the core module content. | ||

| 6 months | Reviews the role of lifestyle factors in illness management (e.g. diet, exercise, smoking). | |||

| 9 months | Review the role of relationships and communication styles. | An additional booster at 9 month time point | ||

| 12 months | Concludes the MoodSwings program and thanks participants for their involvement. | |||

| Additional program elements in upgrade | Participants have access to discussion board 1 per each study arm Monthly discussion topics posted by the moderator | |||

| Participants can view progress within program via progress bar tracking where they are up to in the program | ||||

| Safety red flag protocol also provides feedback to participants when there is reported mood changes | ||||

| Internal messaging system within the program enables secure and confidential communication between researchers and participants | ||||

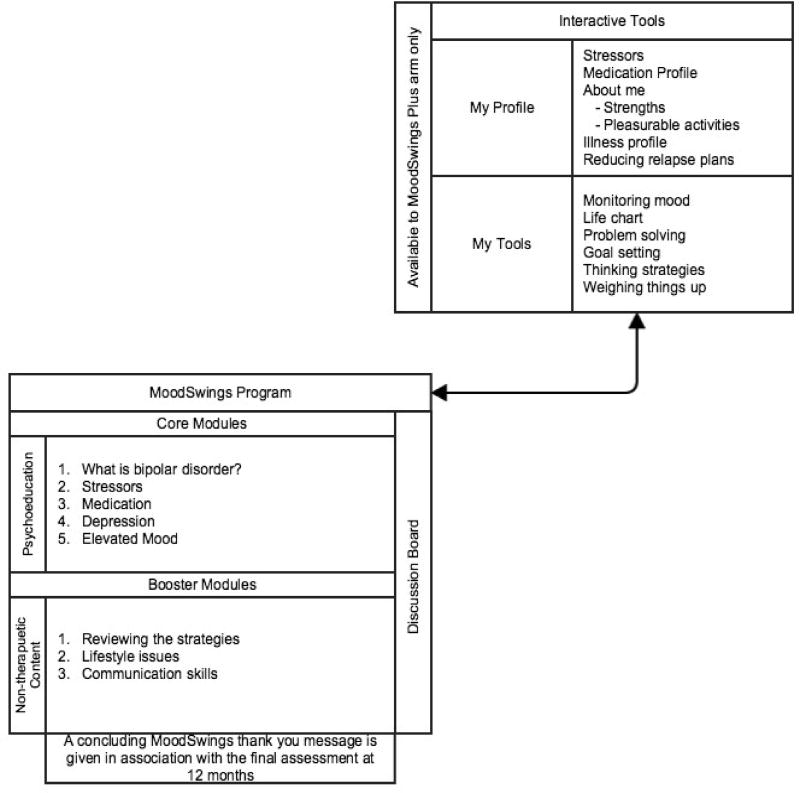

The booster modules provide an incentive for the assessments at these time points and were not designed as primary therapeutic content. The MoodSwings platform hosts 2 online programs on a single website www.moodswings.net.au. The base version referred to as MoodSwings (MS) consists of text based psychoeducation material, supported by video content as part of the MS 2.0 upgrade. The second program is more interactive, and known as MoodSwing Plus (MS-Plus). This program combines the psychoeducation material of MS with interactive elements of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy [6]. Figure 2 provides a site diagram of MoodSwings 2 and the different content available to the two versions of the program, MoodSwings and MoodSwings Plus.

Figure 2.

Site Diagram of MoodSwings 2.0

Following the experiences of the first trial of the MoodSwings program [6], a number of program improvements were implemented, and these are detailed below.

The Technological Changes

MoodSwings 2.0 was moved to the widely used WordPress Content Management System (CMS). Key to the site functionality was the ability to easily monitor participant progress and site usage, greater flexibility for adding and editing site content, and improved navigation and usability for users. This upgrade also allowed the automation of a number of features, including participant randomization and secure private messaging within the site, in accordance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines.

Other technical enhancements include the use of video to supplement the text based material. The flash objects were also upgraded to HTML5 so the site could be viewed on a wide range of internet browsers and electronic devices such as tables and smart phones. The interactive tools included within the program were re-built to improve usability. The mood monitoring tool was also modified to include a measure of sleep hours. This allows users to generate a visual display of the influence sleep can have on mood disturbance, along with monitoring mood, anxiety and irritability.

Another monitoring improvement in MoodSwings 2.0 is the red flag alert system, which is used to monitor participant safety throughout the trial. Participants scoring above clinical cut offs are flagged and researchers notified. A detail of the MoodSwings 2.0 safety monitoring is noted later in this paper.

Content changes

A summary of the MoodSwings program content and the upgraded changes have been noted in table 2. Content updates were minimal and were confined to the revised DSM-5 [30] criteria for bipolar disorder, and updated lists of commonly prescribed medications.

Design changes

Design changes

There were a number of limitations and lessons learnt from the MS 1.0 trial that are able to be addressed in the current study. As a head-to-head trial MS 1.0 did not include a control comparator, the study relied solely on self-report data, was not a replication study, and had a significant loss to follow up which had consequences to the study’s’ power. Points noted as not meeting all Kiluk et al’s [31] quality criteria of methodological strength were addressed. Kiluck et al identified 14 quality criteria for randomised controlled trials, seven of which apply generally to all controlled trials, and seven that relate specifically to online interventions. The quality criteria include; a clear description of the randomisation, follow-up assessment on at least 80% of the sample, the use of validated assessments with the use of raters blinded to participant allocation. Studies need to be adequately powered, and assessed using appropriate statistical analysis and have replication in an independent sample. Quality criteria that apply to online study quality criteria include; appropriate diagnostic measures, intervention is evidence-based, adequate control condition, independent assessments (such as blind ratings), measure of adherence, equivalence across conditions, and include a measure of credibility.

MS 2.0 aimed to address these criteria. The MS 2.0 study provides an independent sample replication of the MS 1.0 content. Additional steps have also been taken to address adherence and follow up attrition. Firstly, the use of phone assessments provide independent assessment of outcomes and also have potential to reduce follow up attrition, as has been noted in previous trials [32]. In addition the follow up independent assessments by blind raters adds to the methodological rigor. Interrater reliability will be conducted annually throughout the trial.

Secondly, the moderated discussion boards as used in MoodSwings 1.0 were designed to assist in engagement in the trial through social support mechanisms. While the boards showed the potential for supportive communication between participants, it was clear that the small groups of six participants per board were not large enough to sustain discussion [6]. The current study includes capacity for three large discussion boards with up to 100 participants. Like MS 1.0 these boards are moderated and posts with inappropriate or concerning content are not made public to the group.

Statistical Methods

The a-priori sample size calculation of 300 with 80% power, assumed a significance level alpha of 0.05, four post assessments, serial correlation equal to 0.4, standard deviation of 10 points and 20% attrition provides confidence that the study is adequately powered

Monitoring Safety

The researchers in internet self-guided studies and interventions do not take on the responsibility of clinical care of the participants. As part of a duty of care as researchers, a number of safety protocols (in addition to the access to care requirement in the inclusion criteria) are utilized within this study.

1 Data Safety Monitoring Board DSMB

To ensure safety of participants, and the validity and integrity of data, a DSMB was established for this trial. The MoodSwings study’s DSMB consists of four external consultants; three psychiatrists based in the USA and a senior pharmacist based at the Australian site, all of who are independent of the trial. The DSMB undertakes a monitoring function, reviews procedures and decisions and advises on scientific and ethical issues regarding the study. In addition the DSMB monitors protocol breaches, oversees the confidentiality of data, quality of data collection, management and analysis. The DSMB also has a reporting responsibility the NIH and sites IRB and ethics committee. Meetings of the DSMB via teleconferencing are scheduled throughout the trial, with additional meetings on an as needed basis.

2 Moderation of all discussion board posts

Prior to any discussion posts appearing on the board, they are reviewed by one of the research moderators (usually within 24 to 48 hours). Moderating the posts enables moderators to prevent inappropriate and distressing material being posted, but also ensures that all posts are reviewed for content that may indicate concerning mood changes. This is a shared responsibility across both sites, and time zone differences enable good coverage of posts.

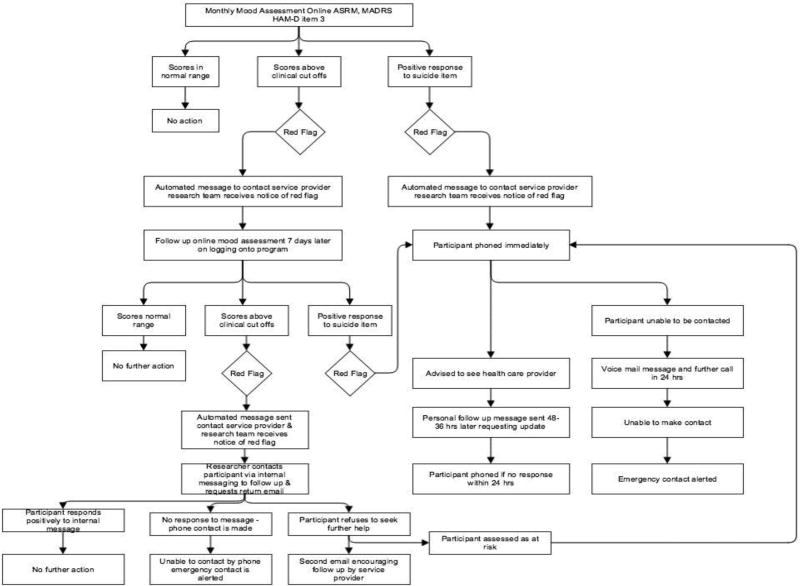

3 The Red flag alert system

The red flag alert system is a detailed algorithm to monitor and respond to mood changes, similar to that employed by other online interventions [5]. Participants are required each month during the trial to respond to brief online mood self-report assessments. Specifically these include the Montgomery Asberg Rating Scale for Depression – Self Report [MADRS-S; [25]. The MADRS-S is a 9 item self rating form of the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; [15] and has high concordance with clinician rated MADRS (r = 0.83–0.93). The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM; [26] is a 5 item multiple-choice scale assessing manic symptoms. It is also reported to be unaffected by self-rater’s level of insight, and is highly correlated with clinical interview [33]. Finally, the HAM-D (item 3) indexes suidicality [12]. The program cannot be accessed until these measures are completed. Each of the measures of this alert system will trigger a ‘red flag’ alert to the researchers if scores exceed the algorithms pre-set thresholds. Figure 3 summarises the MoodSwings 2.0 red flag protocol, which provides guidance to participants who may be clinically unstable. A participant may receive a “Red Flag” via either the online monitoring (including the discussion boards) or telephone assessments. Scores above a validated cut-off on the self-report mood-related measures generate a Red Flag, sending an automated internal email with instructions to the participant to contact his or her health care provider. Most of these alerts are consequent upon elevated overall scores on ratings of depression or mania; in such cases the automated online assessment reassesses mood in seven days. Red Flags generated as a result of clearly expressed suicidal ideation or intent results in a member of the study team calling the participant, and if unsuccessful at making contact, the emergency contact. Those who score highly on assessment measures or expression suicidal ideations at phone assessment are advised to seek appropriate care (e.g. service provider, emergency department). A discussion board moderator also has discretionary ability to generate a Red Flag for participants who express suicidal ideation, plan, or intent via a post. In this case, a participant is contacted via phone.

Figure 3.

Summary of Red Flag Procedure

Discussion

MoodSwings 2.0 builds upon the earlier MoodSwings 1.0 trial with a more rigorous methodology in using both telephone and self report assessments and an attention control condition. It has updated content to be current in line with DSM-5 changes, has discussion boards with greater participant numbers to provide a greater critical mass to enable social support and engagement, and includes technological enhancements of multimedia and graphic displays on a range of devices (computer, ipad, mobile phone). By extending and replicating elements of the earlier trial as well as incorporating recommended methodological standards, MoodSwings 2.0 aims to contribute further to the understanding of the efficacy and role online interventions have in the adjunctive treatment of BD.

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R34MH091384/R34MH091284. MB is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship 1059660.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Uncategorized References

- 1.Castle D, Berk L, Lauder S, Berk M, Murray G. Psychosocial Interventions for Bipolar Disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2009;21:275–284. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauder S, Chester A, Berk M. Net-effect? Online psychological interventions. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2007;19(6):386–388. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohr DC, et al. Perceived barriers to psychological treatments and their relationship to depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;66(4):394–409. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barak A, Hen L, Boniel-Nissim M, Shapira Na. A Comprehensive Review and a Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Internet-Based Psychotherapeutic Interventions. Journal of Technology and Human Services. 2009;26(2/4):109–160. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes CW, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Wilhelm K, Mitchell PB. A web-based preventive intervention program for bipolar disorder: Outcome of a 12-months randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauder S, et al. A randomized head to head trial of MoodSwings.net.au: an Internet based self-help program for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proudfoot J, et al. Effects of adjunctive peer support on perceptions of illness control and understanding in an online psychoeducation program for bipolar disorder: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1–3):98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DJ, et al. Beating Bipolar: exploratory tiral of a novel internet-based psychoeducational treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2011;13:571–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd N, Jones S, Hart A, Lobban F. A web-based self-management intervention for Bipolar Disorder "Living with Bipolar": A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;169:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furukawa TA, et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(3):181–92. doi: 10.1111/acps.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirey JA, et al. The Cornell Service Index as a measure of health service use. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(12):1564–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calabrese J, et al. Lamotrigine demonstrates long-term mood stabilization in bipolar patents with recent episode of mania or hypomania. Eurpoean Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;11(S3) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):321–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2000;42(3):241–7. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart H. Fighting the stigma caused by mental disorders: past perspectives, present activities, and future directions. World Psychiatry. 2008:185–188. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall G, Hays R. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Beek N, Verheul R. Motivation for Treatment in Patients With Personality Disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008:89–100. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental. 2000:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svanborg P, Asberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):21–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman EG, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. The Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(10):948–55. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlbring P, Furmark T, Steczkó J, Ekselius L. An open study of Internet-based bibliotherapy with minimal therapist contact via email for social phobia. Clinical. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein B, et al. Internet-based treatment for panic disorder: does frequency of therapist contact make a difference? Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(2):100–13. doi: 10.1080/16506070802561132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauder SD, et al. Development of an online intervention for bipolar disorder. Psychology Health and Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.689840. http://www.moodswings.net.au. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiluk BD, et al. A methodological analysis of randomized clinical trials of computer-assisted therapies for psychiatric disorders: toward improved standards for an emerging field. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):790–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman E, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. A comparative evaluation of three self-rating scales for acute mania. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(6):468–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]