Abstract

The progress on understanding the pharmacological basis of ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects has been substantial, but appears to have plateaued in the past decade. Further, the cross-species translational efforts are clear in laboratory animals, but have been minimal in human subject studies. Research findings clearly demonstrate that ethanol produces a compound stimulus with primary activity through GABA and glutamate receptor systems, particularly ionotropic receptors, with additional contribution from serotonergic mechanisms. Further progress should capitalize on chemogenetic and optogenetic techniques in laboratory animals to identify the neural circuitry involved in mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. These infrahuman studies can be guided by in vivo imaging of human brain circuitry mediating ethanol’s subjective effects. Ultimately, identifying receptors systems, as well as where they are located within brain circuitry, will transform the use of drug discrimination procedures to help identify possible treatment or prevention strategies for alcohol use disorder.

Keywords: Alcohol, Drug discrimination, Ethanol, Interspecies, Translational

1 Introduction

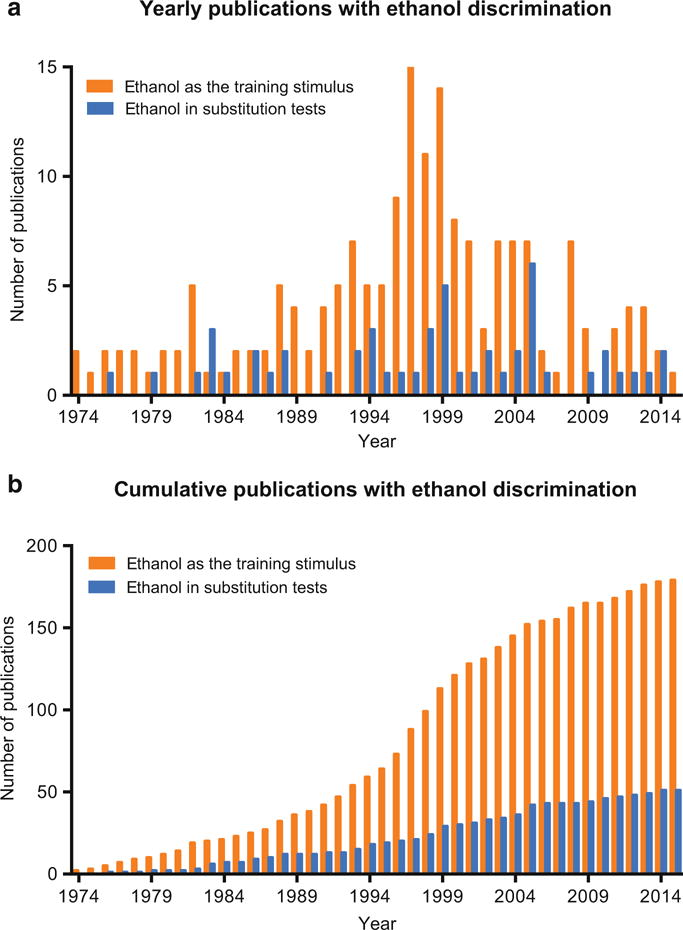

Although reports of state dependent learning using alcohol go back to the 1950s [1], the study of the pharmacological basis of the ethanol discriminative stimulus began in earnest in the early 1970s. The literature reviewed here comprises reports in which ethanol was used as a training stimulus as well as manuscripts that used ethanol in substitution tests for other drugs used as training stimuli. Studies that report only subjective effects or reinstatement procedures are not included in this review. In general, given that the cumulative dataset encompasses over four decades of research, the volume of studies addressing the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol is not large. Figure 1 depicts both the cumulative publications (Fig. 1a) and the yearly publication rate (Fig. 1b) reporting ethanol trained as a discriminative stimulus as well as ethanol substitution tests in other drug discriminations. Most of the substitution tests using ethanol were either to control for nonspecific drug effects (i.e., as a negative control for discriminative stimuli other than ethanol) or to test for cross-generalization. These contributions have been at a low, but fairly consistent rate over time (Fig. 1b). Overall, for studies that trained an ethanol discrimination there has been about 4–5 publications/year, but the timeframe of 1990–2005 was clearly the most productive (Fig. 1a). Publications have fallen off considerably since 2005. This trend is remarkably similar to the trend encompassing the entire drug discrimination literature as recently reviewed [2]. The reason for this decline in the use of ethanol discrimination in understanding the behavioral pharmacology of ethanol is not readily obvious. Given the utility of drug discrimination as an in vivo pharmacological assay, there clearly remain many important questions that can be addressed with an ethanol discrimination preparation, particularly in the context of recent advancements in brain-region specific targeting and genetic manipulations. Neurobiological approaches, including chemogenetic and optogenetic manipulations, have the potential to greatly expand our knowledge of dose-dependent mechanisms of ethanol in the brain and improve cross-species translational cohesion of the interoceptive effects of ethanol. In general, animal models of human behavior ultimately strive to provide data that inform the human condition. In alcohol discrimination procedures, this emphasis is on pharmacological variables and receptor mechanisms that mediate the stimulus effects and a rational approach to pharmacotherapeutic development for alcohol use disorders. However, specificity in terms of discrete neural circuitry to target and lower adverse off target effects has not been achieved, but represents an important avenue forward.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative (a) and yearly (b) publication rate for ethanol as a training stimulus and in substitution tests

Although circuitry and genomic approaches are only just beginning to be applied to ethanol discriminations, ethanol is one substance that has a relatively strong record in cross-species translational studies. Ethanol has been trained as a discriminative stimulus in pigeons, mice, rats, gerbils, monkeys, and humans, although not in a proportional fashion. Indeed, the contribution to the literature can be rank ordered by rodents (89%), monkeys (7%), pigeons (2%), and humans (2%). Somewhat perplexing, given the legal and historical status of alcohol, there are far fewer human subject studies of ethanol discrimination than there are of stimulant, opiate, or cannabinoid discriminations (reviewed in Bolin et al. [2] and in the section below).

Given the low rate of new data on ethanol discrimination in recent years, an in-depth review of the basic pharmacology underlying ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects would add little to available reviews on the subject [3–6]. Instead, this review focuses on more recent developments in refining the specific action of ethanol at each receptor target. Specifically, the receptor systems that are primarily identified in rodents will be compared and contrasted with findings from monkeys and humans in order to highlight whether this information has been translated across species. A major conclusion is that in order for ethanol discrimination studies to advance pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorders, a new approach is needed. Specifically, the future of translational ethanol discrimination studies must focus on region specific receptor mechanisms and how this fits into a cohesive understanding of brain circuitry. Over the last four decades, ethanol drug discrimination studies have established three primary receptor targets involved in ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects: GABAA, NMDA, and 5-HT1B/2C systems. There has also been some evidence for a secondary, modulatory role of both the opioid [7–11] and acetylcholine [12–16] receptor systems, but there is no evidence of direct mediation of ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects at these receptor sites. Ethanol is known to act as a positive modulator at the GABAA receptor to increase chloride conductance through the channel and decrease cellular excitability [17]. Additionally, ethanol has antagonist activity at the NMDA glutamate receptor, which appears selective for noncompetitive antagonism. Lastly, ethanol has activity at several 5-HT receptor systems, but agonism at the 5-HT1B/2C receptor subtypes is most prominent [4, 6, 18].

Somewhat unique to ethanol, the relative contribution of these stimulus components varies based on training dose magnitude, with GABAA receptors exerting greatest influence at low to moderate training doses (≤1.5 g/kg) and NMDA receptors playing a larger role at higher doses (≥1.5 g/kg) in rodents [6, 19, 20]. Similarly, the 5-HT component of the ethanol stimulus complex is most prominent at low to moderate training doses [21]. More recent work expands upon this foundation and emphasizes the selectivity of ethanol at different receptor subtypes and subunits by incorporating novel ligands. To compare data across species, findings from systemic administration are surveyed in the following sections, with an additional section emphasizing recent work with targeted brain-region approaches. At the conclusion, suggestions for future approaches are presented to maximize the utility of ethanol discrimination procedures for pharmacotherapy development.

1.1 Rodents

1.1.1 GABA

The GABAA receptor complex is integral to many of ethanol’s behavioral and physiological effects (e.g., [17, 22]). Consistent with ethanol’s action as a positive modulator at the GABAA receptor, drugs in the benzodiazepine and barbiturate classes, with a similar mechanism to modulate chloride flow through the GABAA receptor, consistently produce ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects (reviewed in Grant [4]). More recent work has expanded upon these findings in two primary ways. First, the specific action of ethanol at GABAA receptors with distinct subunit compositions has been investigated using a combination of genetic knockout and selective ligand approaches. Second, the selective role of neurosteroid activity at the GABAA receptor has been confirmed, and consistent with the action of neurosteroids as positive allosteric modulators at GABAA, they exhibit ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects similar to those generated by the benzodiazepine and barbiturate drug classes.

The GABAA receptor is a pentameric transmembrane receptor, classically made up of two alpha (α) subunits, two beta (β) subunits, and one gamma (γ) subunit. A delta (δ) subunit may substitute for a γ subunit in some receptor isoforms. Ethanol discrimination studies have primarily focused on isolating the role of α1-, α4/6-, and δ-subunit-containing receptors. Specifically, zolpidem, an α1 subunit-preferring benzodiazepine agonist, partially substitutes for ethanol in rats [23], but does not produce ethanol-like stimulus effects in mice [24], suggesting that activity at the α1 subunit is not sufficient to produce ethanol discriminative stimulus effects in rodents. Additionally, ethanol’s action at a4/6-subunits has been investigated using Ro 15-4513, an inverse agonist at the benzodiazepine binding site, with some selectivity for the α4/6-subunits. While Ro 15-4513 successfully antagonizes the discriminative stimulus effects of benzodiazepine, the results are mixed for ethanol-trained rodents, with some studies showing antagonism of ethanol’s discriminative effects [25, 26], and others showing no antagonism [27, 28]. The mixed effects of Ro 15-4513 as an ethanol antagonist are likely due to the differences in training doses and routes, suggesting that the prominence of the α4/6-subunits in ethanol discrimination is dependent on experimental parameters that might influence BEC. The δ-subunit of the GABAA receptor complex has also been isolated in ethanol discrimination using a constitutive δ-subunit knockout line of mice, and the results indicated that there were no differences in either the acquisition of ethanol discrimination or the substitution patterns of the GABAA receptor positive modulators compared to wild-type mice [24]. Therefore the δ-subunit of GABAA receptors is not necessary for mediating ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects or for the substitution of benzodiazepines, barbiturates, or neurosteroids. The δ-subunit is thought to be an identifying feature of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors that mediate tonic inhibitory currents and confer sensitivity to low doses of ethanol [29, 30], and thus, these findings suggest that either non-δ extrasynaptic or synaptic receptors associated with phasic inhibitory currents may be more prominent in producing the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol.

The steroid binding site on GABAA receptors and its modulation by neuroactive steroids has received considerable attention because these endogenous compounds respond to stress and are implicated in a number of behavioral disorders [31]. Neuroactive steroids that act at GABAA receptors do so through binding sites that are distinct from the benzodiazepine and barbiturate sites, and the conformation of the steroid A-ring 3′ and 5′ carbon hydroxyl groups is the key to receptor activation (see Chen et al. [32]). Select neuroactive steroids generalize from an ethanol training stimulus in rodents, including the reduced metabolites of progesterone (allopreg-nanolone or 3α,5α-P; pregnanolone or 3α,5β-P; and epipregnanolone or 3β,5β-P) and deoxycorticosterone (allotetrahydro-deoxycorticosterone or 3α,5α-THDOC) [33, 34]. Substitution was more prominent at a lower training dose (1 g/kg, i.g.) versus a higher one (2 g/kg, i.g.) [34]. The ethanol route of administration may also play a role in substitution patterns as 3β,5β-P has mixed effects in ethanol discriminations. 3β,5β-P produced no generalization with ethanol trained via an intraperitoneal route [34] but produced complete substitution, as well as potentiation of the ethanol cue, when trained with an intragastric route [33, 35]. Finally, the neurosteroid substitution patterns for ethanol suggest sex differences in sensitivity. For example, in contrast to earlier studies in male rats [33, 34], female rats showed only partial substitution of allopregna-nolone and pregnanolone for a 1 g/kg ethanol training dose [36]. This latter finding is consistent with earlier work demonstrating that females were less sensitive to the modulatory effects of allopregnanolone on ethanol drinking behavior when compared to males [37]. Collectively, these and other studies (e.g., [38]) suggest that GABAA receptors that contain a neurosteroid binding site contribute to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Similar to barbiturates and benzodiazepines, neuroactive steroids asymmetrically cross-generalize with ethanol, with only partial substitution when ethanol is substituted in pregnanolone-trained rats [39–41] and mice [42]. This asymmetrical cross-generalization likely reflects the inability of pregnanolone and related neuroactive steroids to encompass other aspects of the compound ethanol cue.

1.1.2 Glutamate

The NMDA glutamatergic receptor is also well established in contributing to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol, particularly at higher doses in rodents [8]. Consistent with ethanol’s known action as an NMDA antagonist at the synapse [17], drug discrimination studies have established that antagonism of the NMDA receptor produces ethanol-like discriminative effects. One of the earliest studies determined that the noncompetitive channel blocker dizocilpine (i.e., MK-801) fully substituted for ethanol in pigeons [43], and this finding has been replicated in rodents, including multiple strains of rats [19,44–48] and mice [24, 49]. Other NMDA channel blockers such as memantine, phencyclidine (PCP), and ketamine have yielded similar degrees of substitution for ethanol in rats [19, 45, 47]. Often, however, substitution requires doses of the NMDA antagonists that also attenuate response rates [44, 50] to the extent that full substitution by these compounds is precluded [51].

In addition to the channel blocker site, multiple binding sites on the NMDA receptor have been examined, including the glutamate, glycine, and polyamine sites. Overall, ligands for each of these other binding sites have been far less effective in producing ethanol-like stimulus effects, indicating that ethanol’s action is most similar to the non-competitive activity at the channel pore. Competitive antagonists at the glutamate site have generalized from ethanol in some cases (CGS 19755) [47], but have only partially substituted in other cases (CPPene, NPC-17742) [44, 51]. Similar results have been found with glycine site antagonists, with some ligands producing full substitution (L701,324) [50, 52], and others not substituting at all (MRZ2-502 and MRZ2-576) [45, 50]. Lastly, polyamine binding site antagonists (eliprodil and arcaine) produce stimulus effects that do not generalize from ethanol [45, 47]. In conclusion, the contribution of the glutamate, glycine, and polyamine binding sites of the NMDA receptor appears minimal in ethanol discrimination, particularly when compared to the channel pore site. However, it is noteworthy that aforementioned studies were all conducted in rats trained to discriminate a low to moderate dose of ethanol (i.e., 1 g/kg), and it is possible that inconsistent findings between studies may be partially attributable to the training dose studied, as previous work indicates that NMDA receptors contribute more predominantly to the ethanol stimulus at higher doses (>1.5 g/kg) in rodents [6, 19, 52].

In addition to the NMDA receptor, recent studies have begun to examine the metabotropic glutamate system (mGluR1, mGluR2/3, and mGluR5) based on findings that the mGluR5 receptor might modulate activity at the GABAA receptor [53]. Selective mGluR5 antagonist MPEP antagonized the ethanol dose-response function by decreasing the potency for ethanol to substitute for itself [53–55]. An mGluR2/3 agonist also decreased the potency of ethanol discrimination [56], but no effect was observed with any of the mGluR1 antagonists tested [54]. These studies have provided a novel pharmacological target for ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects, although it should be noted that these effects are modulatory in nature, and they are not sufficient to produce ethanol-like effects on their own. Thus, the direct glutamatergic activity of ethanol remains primarily at the NMDA receptor.

1.1.3 Serotonin

The importance of serotonergic neurotransmission in ethanol discriminative stimulus effects was first reported with the observation that pretreatment with a tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor (p-chlorophenylalanine; which depletes brain 5-HT) reduces compartment choice between ethanol and water to chance levels in rats studied within a shock avoidance-based discrimination paradigm [57]. Since then, there have been several studies to manipulate levels of synaptic 5-HT, through enhancing 5-HT release (fenfluramine), a nonselective 5-HT receptor agonist (5-MeODMT), and selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine and paroxetine). In general, only SSRIs have produced ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects [58], but this may be mediated through a non-serotonergic mechanism via their augmentation of brain allopregnanolone levels [59], which would be expected to exert positive modulation of GABAA receptors.

The first 5-HT receptor to be examined in an ethanol discrimination preparation was the 5-HT3 receptor [60], which is an ionotropic receptor, and therefore from the same superfamily of receptors as the GABAA and NMDA receptors. Although studies in rats have found that 5-HT3 receptor agonists (mCPBG) and antagonists (ICS 205–930) do not generalize from ethanol [61, 62], there is some limited evidence in pigeons that 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (ICS 205-930 and MDL 72222) block the discriminative stimulus effects of low to moderate ethanol doses [63]. These data suggest that contribution of 5-HT3 receptors in producing discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol is likely minimal. This conclusion is also supported by data from transgenic mice that overexpress 5-HT3 receptors and show no differences in their ability to acquire an ethanol discrimination or in the substitution profiles with GABAA receptor positive modulators and an NMDA receptor antagonist when compared to wild-type mice [64].

In contrast to nonselective or selective 5-HT3 receptor agonists, there is sufficient evidence to indicate a role for agonism at metabotropic 5-HT receptor subtypes in ethanol discrimination. From an initial characterization of several 5-HT receptor agonists in rats, the only compound to yield full substitution for ethanol in rats was TFMPP, a relatively nonselective 5-HT1 agonist with slightly greater affinity for the 1A isoform [65]. This finding with TFMPP was replicated in both male [21] and female [36] rats. Subsequent evaluations of multiple compounds with various 5HT receptor agonist profiles in male rats revealed that CGS 12066B and CP 94,253 (both selective for 5-HT1B) or mCPP and RU 24969 (both selective for 5-HT1B/2C) fully generalized from ethanol (1 g/kg), whereas 8-OH DPAT (5-HT1A) and DOI (5-HT2A) did not 66–68]. A parallel set of antagonism studies used subtype selective antagonists to completely block the ethanol-like effects of CP 94,253 and mCPP [67], leading to an overall conclusion that 5-HT1B and 5-HT2C receptors contribute to the ethanol cue. However, there are inconsistencies in the generalizability of 5-HT1B/2C agonists to substitute for ethanol across sex and species, as RU 24969 only partially substituted for ethanol in female rats [36] and mCPP did not generalize from ethanol in mice [64]. Refinement of receptor ligands with increased selectivity for 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptor isoforms (e.g., [69, 70]) coupled with a rapid expansion of novel ligand development for 5-HT4 receptors, which also function to regulate neurotransmission in conjunction with 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors [71, 72], should prompt a fresh look at the involvement of metabotropic 5-HT receptors in modulating the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol.

1.2 Nonhuman Primates

Ethanol discrimination in monkeys has built upon findings from rodents in several key ways. In general, nearly all of the receptor targets of ethanol in monkeys have been taken from the rodent literature and are largely consistent across species. However, there are several important differences between the rodent and the monkey that may inform future clinical work and shed light on potential limitations of smaller laboratory animals in ethanol discrimination. Nonhuman primate studies have primarily focused on ethanol’s action at the GABAA and NMDA receptors, with some work on the opioid system. Additionally, nonhuman primate work has examined other biological variables that may contribute to ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects, such as sex [73–76], age [77], and menstrual cycle [78].

Ethanol’s action at the GABAA receptor is highly selective in nonhuman primates. Specifically, studies in monkeys have examined subunit-selective ligands and antagonists at the GABAA receptor [75, 79–81], as well as neuroactive steroid activity [74, 78, 82, 83]. Additionally, cross-generalization analysis was possible by studies that trained ethanol-like GABAA ligands and examined ethanol in substitution tests [79, 84–86]. Similar to rodents, direct agonists at the GABAA receptor fail to produce ethanol discriminative stimulus effects, but positive allosteric modulators reliably substitute for ethanol [73]. Specifically, positive modulators at the benzodiazepine and barbiturate binding sites produce the most robust ethanol-like effects [73]. In contrast to rodents, however, GABAA modulators produce full substitution at low and high training doses (1.0–2.0 g/kg), rather than just predominantly at lower doses. Converging evidence from multiple studies suggests that α5 subunit-containing receptors are particularly important in ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects [75, 80, 81], as well as some contribution of the α1 and α2/3 subunits. Alpha-5 and alpha-1 selective agonists substitute for ethanol, but only inverse agonists selective for α5 (L-655,708) and α5 + α4/6 (Ro-154513) are able to antagonize ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects [75, 87]. Ro-154513 is also able to antagonize the substitution of benzodiazepines and barbiturates for ethanol, suggesting a shared action at the GABAA subunit level [76]. Neuroactive steroids also selectively produce ethanol-like discriminative effects based on their pharmacological effect at the GABAA receptor. Specifically, 3-alpha-hydroxy metabolites of progesterone such as allopregnanolone and pregnanolone are positive modulators at the GABAA receptor and produce ethanol-like stimulus effects in male and female monkeys [74, 82, 83]. However, 3-beta-hydroxy metabolites do not reliably substitute for ethanol at any training dose [80]. Several studies in monkeys have trained GABAA ligands and tested ethanol for substitution. To summarize this work, ethanol only cross-substituted with pentobarbital [85], but did not substitute for midazolam [86] or lorazepam [84]. These data suggest that ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects in the monkey are more similar to barbiturates, as compared to benzodiazepines.

Ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects are also mediated by antagonist activity at the NMDA receptor, and may be modulated by the opioid system. Noncompetitive antagonists at the channel pore MK-801 (or dizocilpine) and PCP produce full substitution for ethanol in male and female monkeys, but (unlike rodents) ketamine has not produced full substitution [76]. NMDA antagonist substitution was most potent and efficacious at a lower training dose, which is also in contrast to studies in rodents suggesting that a higher ethanol training dose conferred greater NMDA antagonism substitution [6] (see Sect. 1.1 above). These data are consistent with rodent data in characterizing ethanol as a compound stimulus in the monkey, with activity at both GABAA and NMDA receptors. Further, there has been a limited attempt to characterize the role of mu and delta opioid receptors in mediating the ethanol cue in monkeys. This examination found that selective agonists at both the mu (i.e., morphine and fentanyl) and delta (i.e., SNC 80 and SNC 162) receptors did not produce ethanol-like stimulus effects [73, 87], indicating that the opioid system is likely not aprimary target in ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects. However, nonselective antagonist naltrex-one antagonized the ethanol dose-response relationship [87], suggesting that the opioid system may function as a modulator of the ethanol stimulus, adding to the complex basis of the ethanol cue.

Lastly, nonhuman primate studies have taken advantage of the overlapping physiology between humans and monkeys to examine biological variables that may contribute to ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects. Most notably, a few of the nonhuman primate studies have directly compared male and female subjects in the analysis of GABAA and NMDA receptor involvement in ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects [73, 76]. Though there are small differences between male and female monkeys, in general the pharmacological basis of the ethanol cue is shared across the sexes. One exception relates to neurosteroid substitution for ethanol, which appears dependent on the phase of the menstrual cycle in female monkeys [78, 83]. In the luteal phase, when progesterone levels are high, allopregnanolone is more potent in its substitution for ethanol, consistent with greater levels of allopregnanolone in the plasma. Lastly, one study examined the effect of age on ethanol discriminative stimulus effects and determined that ethanol served as a relatively weaker stimulus in middle-aged monkeys, despite elevated blood ethanol concentrations relative to when the same monkeys were young adults [77]. Additionally, this study demonstrated that ethanol discrimination was persistent and demonstrated up to 3 years without any intermediate training [77].

1.3 Humans

To our knowledge, there are only five reports of training ethanol as a discriminative stimulus in human subjects [88–92] and one report of ethanol substitution in a nicotine-trained discrimination, in which it did not substitute [93]. These studies primarily demonstrated that ethanol can be trained with equal sensitivity in male and female subjects [88, 91], but the acquisition is sensitive to baseline weekly alcohol intake [89, 90] and ethanol generalization occurs in a dose-dependent manner [88, 89, 92]. The only study to test a compound other than ethanol examined the benzodiazepine lorazepam and found complete substitution [91]. Thus, the only receptor system directly implicated in the basis of an ethanol discrimination in humans is the GABAA receptor system.

1.4 Neuroanatomical Targets

In the last 20 years, there have been a handful of laboratories that have investigated the neuroanatomical basis of ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects. These studies have been conducted exclusively in rodents and have focused on the GABA and glutamate components of the ethanol cue using intracranial site-specific microinjections. Additionally, some work has been done measuring c-Fos activation after performance of an ethanol discrimination to identify the primary brain regions involved in ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects and the direction (activation or inactivation) of their involvement. A majority of these studies are based on an initial finding that agonism of the GABAA receptor in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) produced full substitution for ethanol [94]. Since then, GABAA positive modulators such as pentobarbital and allopregnanolone administered into the NAc core have also produced full ethanol substitution [94–96]. However, ethanol substitution is not blocked by the GABAA antagonist bicuculline in the NAc indicating that GABAA receptors within the NAc are sufficient, but not necessary to produce ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects [94]. This is supported by work demonstrating that NMDA antagonist MK-801 in the NAc also produces full substitution for ethanol [96], and there appears to be some secondary contribution of mGlu5 receptors in the NAc, consistent with systemic administration of these compounds [54]. Thus, it appears that within the NAc, ethanol is acting as a compound cue on GABA and glutamate systems. It is important to note that these findings are highly consistent with ethanol’s known action to activate GABAA and inhibit NMDA activity within the NAc in slice electrophysiology studies [17, 97, 98], resulting in an overall suppression of neuronal firing. This is further supported by c-Fos studies in discrimination-trained rats demonstrating decreased c-Fos activity within the NAc after ethanol [99, 100].

In addition to the NAc, there have also been select studies examining the role of the amygdala, several cortical areas (mPFC, prelimbic, and insula), hippocampus, and thalamus (rhomboid nucleus). In general, these primarily limbic brain regions have been demonstrated to contribute to some extent to ethanol’s discriminative stimulus effects. Interestingly, these brain areas appear to have some selectivity for whether they are involved primarily in ethanol’s GABAergic or glutamatergic component. Specifically, GABAA modulation in the amygdala produces ethanol-like effects, but there is no evidence for this brain region in the NMDA component [96, 101]. Conversely, NMDA the antagonist MK-801 in the prelimbic cortex and hippocampus produced full ethanol substitution, but GABAA agonists did not substitute [96]. The mPFC, insula, and rhomboid thalamus have also been shown to contribute to the GABA component through pharmacological inactivation using a GABAA + GABAB cocktail [100]. This fairly limited body of literature raises some important questions that can be addressed with future research. A differential contribution of different brain structures to the compound ethanol cue strongly suggests that our focus should be redirected to understanding sensitive circuitry mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Because the preliminary data on sensitive brain areas (not circuitry per se) is exclusively derived in rodent subjects, replicating and extending these results to the primate brain is needed.

1.5 New Paradigm for Advancing Knowledge and Pharmacotherapeutic Development with Ethanol Discriminations

From a translational perspective, these brain circuitry studies in rodents provide a strong foundation for potential target sites for future work in monkeys and humans. The recent development of chemogenetic or optogenetic approaches, using viral-based molecular targeting strategies, will allow for repeated manipulation of specific brain nuclei to understand their role in mediating the ethanol cue. Additionally, application of fMRI techniques in humans can examine the connectivity patterns of brain activation in mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. The combination of human brain mapping and functional testing of identified areas in animal models with molecular targeting approaches will open up a new understanding of how the subjective effects of ethanol are mediated. Overall, although the number of laboratories involved in ethanol discrimination studies appears to be declining, these new technologies are likely to revive interest in knowing how the ethanol cue is mediated and its role in the subjective effects that maintain human alcohol consumption.

Contributor Information

Daicia C. Allen, Department of Behavioral Neurosciences, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA

Matthew M. Ford, Division of Neuroscience, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA

Kathleen A. Grant, Division of Neuroscience, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA

References

- 1.Conger JJ. Alcoholism: theory, problem and challenge. II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolin BL, Alcorn JL, Reynolds AR, Lile JA, Rush CR. Human drug discrimination: a primer and methodological review. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;24:214–228. doi: 10.1037/pha0000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry H. Distinctive discriminative effects of ethanol. NIDA Res Monogr. 1991;116:131–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant KA. Emerging neurochemical concepts in the actions of ethanol at ligand-gated ion channels. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:383–404. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodge CW, Grant KA, Becker HC, Besheer J, Crissman AM, Platt DM, Shannon EE, Shelton KL. Understanding how the brain perceives alcohol: neurobiological basis of ethanol discrimination. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolerman IP, Childs E, Ford MM, Grant KA. Role of training dose in drug discrimination: a review. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:415–429. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328349ab37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mhatre M, Holloway F. Micro1-opioid antagonist naloxonazine alters ethanol discrimination and consumption. Alcohol. 2003;29:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middaugh LD, Kelley BM, Cuison ER, Jr, Groseclose CH. Naltrexone effects on ethanol reward and discrimination in C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:456–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middaugh LD, Kelley BM, Groseclose CH, Cuison ER., Jr Delta-opioid and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist effects on ethanol reward and discrimination in C57BL/6 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shippenberg TS, Altshuler HL. A drug discrimination analysis of ethanol-induced behavioral excitation and sedation: the role of endogenous opiate pathways. Alcohol. 1985;2:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(85)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter JC. The stimulus properties of morphine and ethanol. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;44:209–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00428896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bienkowski P, Kostowski W. Discrimination of ethanol in rats: effects of nicotine, diazepam, CGP 40116, and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)-biguanide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford MM, McCracken AD, Davis NL, Ryabinin AE, Grant KA. Discrimination of ethanol-nicotine drug mixtures in mice: dual interactive mechanisms of overshadowing and potentiation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;224:537–548. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2781-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford MM, Davis NL, McCracken AD, Grant KA. Contribution of NMDA glutamate and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mechanisms in the discrimination of ethanol-nicotine mixtures. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24:617–622. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283654216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korkosz A, Taracha E, Plaznik A, Wrobel E, Kostowski W, Bienkowski P. Extended blockade of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine with low doses of ethanol. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;512:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Ethanol does not affect discriminative-stimulus effects of nicotine in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;519:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovinger DM, Roberto M. Synaptic effects induced by alcohol. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2013;13:31–86. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stolerman IP, Mariathasan EA, White JA, Olufsen KS. Drug mixtures and ethanol as compound internal stimuli. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grant KA, Colombo G. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol: effect of training dose on the substitution of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colombo G, Grant KA. NMDA receptor complex antagonists have ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654:421–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant KA, Colombo G. Substitution of the 5-HT1 agonist trifluoromethylphenylpipera-zine (TFMPP) for the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol: effect of training dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113:26–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02244329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breese GR, Criswell HE, Carta M, Dodson PD, Hanchar HJ, Khisti RT, Mameli M, Ming Z, Morrow AL, Olsen RW, Otis TS, Parsons LH, Penland SN, Roberto M, Siggins GR, Valenzuela CF, Wallner M. Basis of the gabamimetic profile of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:731–744. doi: 10.1111/j.0145-6008.2006.00086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bienkowski P, Iwinska K, Stefanski R, Kostowski W. Discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol in the rat: differential effects of selective and nonselective benzodiazepine receptor agonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:969–973. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon EE, Shelton KL, Vivian JA, Yount I, Morgan AR, Homanics GE, Grant KA. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in mice lacking the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor delta subunit. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:906–913. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128227.28794.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees DC, Balster RL. Attenuation of the discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol and oxazepam, but not of pentobarbital, by Ro 15-4513 in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatto GJ, Grant KA. Attenuation of the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol by the benzodiazepine partial inverse agonist Ro 15-4513. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8:139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiltunen AJ, Järbe TUC. Effects of Ro 15-4513, alone or in combination with ethanol, Ro 15-1788, diazepam, and pentobarbital on instrumental behaviors of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;31:597–603. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middaugh LD, Bao K, Becker HC, Daniel SS. Effects of Ro 15-4513 on ethanol discrimination in C57BL/6 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;38:763–767. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carver CM, Reddy DS. Neurosteroid structure-activity relationships for functional activation of extrasynaptic δGABA(A) receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;357:188–204. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul SM, Purdy RH. Neuroactive steroids. FASEB J. 1992;6:2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen ZW, Manion B, Townsend RR, Reichert DE, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Sieghart W, Fuchs K, Evers AS. Neurosteroid analog photolabeling of a site in the third transmembrane domain of the β3 subunit of the GABAA receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:408–419. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.078410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ator NA, Grant KA, Purdy RH, Paul SM, Griffiths RR. Drug discrimination analysis of endogenous neuroactive steroids in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;241:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowen CA, Purdy RH, Grant KA. Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of endogenous neuroactive steroids: effect of ethanol training dose and dosing procedure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginsburg BC, Lamb RJ. Alphaxalone and epiallopregnanolone in rats trained to discriminate ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1621–1629. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179374.39554.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helms CM, McCracken AD, Heichman SL, Moschak TM. Ovarian hormones and the heterogeneous receptor mechanisms mediating the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in female rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24:95–104. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32835efc5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finn DA, Beckley EH, Kaufman KR, Ford MM. Manipulation of GABAergic steroids: sex differences in the effects on alcohol drinking- and withdrawal-related behaviors. Horm Behav. 2010;57:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bienkowski P, Kostowski W. Discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol in the rat: effects of neurosteroids and picrotoxin. Brain Res. 1997;753:348–352. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engel SR, Purdy RH, Grant KA. Characterization of discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerak LR, Moerschbaecher JM, Winsauer PJ. Overlapping, but not identical, discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone and ethanol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vanover KE. Effects of benzodiazepine receptor ligands and ethanol in rats trained to discriminate pregnanolone. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:483–487. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shannon EE, Porcu P, Purdy RH, Grant KA. Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of the neuroactive steroid pregnanolone in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J inbred mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:675–685. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grant KA, Knisely JS, Tabakoff B, Barrett JE, Balster RL. Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of non-competitive n-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists. Behav Pharmacol. 1991;2:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shelton KL, Balster RL. Ethanol drug discrimination in rats: substitution with GABA agonists and NMDA antagonists. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:441–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hundt W, Danysz W, Hölter SM, Spanagel R. Ethanol and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex interactions: a detailed drug discrimination study in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;135:44–51. doi: 10.1007/s002130050484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kotlinska J, Liljequist S. The NMDA/glycine receptor antagonist, L-701,324, produces discriminative stimuli similar to those of ethanol. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;332:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanger DJ. Substitution by NMDA antagonists and other drugs in rats trained to discriminate ethanol. Behav Pharmacol. 1993;4:523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schechter MD, Meehan SM, Gordon TL, McBurney DM. The NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 produces ethanol-like discrimination in the rat. Alcohol. 1993;10:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90035-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shelton KL, Grant KA. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:747–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bienkowski P, Danysz W, Kostowski W. Study on the role of glycine, strychnine-insensitive receptors (glycineB sites) in the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in the rat. Alcohol. 1998;15:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(97)00103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shelton KL. Substitution profiles of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists in ethanol-discriminating inbred mice. Alcohol. 2004;34:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grant KA, Colombo G. Pharmacological analysis of the mixed discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1993;2:445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Besheer J, Hodge CW. Pharmacological and anatomical evidence for an interaction between mGluR5- and GABA(A) alpha1-containing receptors in the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:747–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Besheer J, Grondin JJ, Salling MC, Spanos M, Stevenson RA, Hodge CW. Inter-oceptive effects of alcohol require mGlu5 receptor activity in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9582–9591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2366-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Besheer J, Stevenson RA, Hodge CW. mGlu5 receptors are involved in the discriminative stimulus effects of self-administered ethanol in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;551:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cannady R, Grondin JJ, Fisher KR, Hodge CW, Besheer J. Activation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits the discriminative stimulus effects of alcohol via selective activity within the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2328–2338. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schechter MD. Ethanol as a discriminative cue: reduction following depletion of brain serotonin. Eur J Pharmacol. 1973;24:278–281. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(73)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maurel S, Schreiber R, De Vry J. Substitution of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors fluoxetine and paroxetine for the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130:404–406. doi: 10.1007/s002130050257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A. Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:362–372. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lovinger DM. Ethanol potentiation of 5-HT3 receptor-mediated ion current in NCB-20 neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci Lett. 1991;122:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90192-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mhatre MC, Garrett KM, Holloway FA. 5-HT 3 receptor antagonist ICS 205-930 alters the discriminative effects of ethanol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:163–170. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stefanski R, Bienkowski P, Kostowski W. Studies on the role of 5-HT3 receptors in the mediation of the ethanol interoceptive cue. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;309:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grant KA, Barrett JE. Blockade of the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;104:451–456. doi: 10.1007/BF02245648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shelton KL, Dukat M, Allan AM. Effect of 5-HT3 receptor overexpression on the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1161–1171. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000138687.27452.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Signs SA, Schechter MD. Nicotine-induced potentiation of ethanol discrimination. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24:769–771. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grant KA, Colombo G, Gatto GJ. Characterization of the ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of 5-HT receptor agonists as a function of ethanol training dose. Psycho-pharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:133–141. doi: 10.1007/s002130050383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maurel S, Schreiber R, De Vry J. Role of 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in the generalization of 5-HT receptor agonists to the ethanol cue in the rat. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Szeliga KT, Grant KA. Analysis of the 5-HT2 receptor ligands dimethoxy-4-indophenyl-2-aminopropane and ketanserin in ethanol discriminations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:646–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gupta S, Villalón CM. The relevance of preclinical research models for the development of antimigraine drugs: focus on 5-HT(1B/1D) and CGRP receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;128:170–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jensen NH, Cremers TI, Sotty F. Therapeutic potential of 5-HT2C receptor ligands. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1870–1885. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bureau R, Boulouard M, Dauphin F, Lezoualc’h F, Rault S. Review of 5-HT4R ligands: state of art and clinical applications. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:527–553. doi: 10.2174/156802610791111551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fink KB, Göthert M. 5-HT receptor regulation of neurotransmitter release. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:360–417. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grant KA, Waters CA, Green-Jordan K, Azarov A, Szeliga KT. Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of GABA A receptor ligands in Macaca fascicularis monkeys under different ethanol training conditions. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152:181–188. doi: 10.1007/s002130000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grant KA, Helms CM, Rogers LSM, Purdy RH. Neuroactive steroid stereospecificity of ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:354–361. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Helms CM, Rogers LSM, Grant KA. Antagonism of the ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol, pentobarbital, and midazolam in cynomolgus monkeys reveals involvement of specific GABA(A) receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:142–152. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vivian JA, Waters CA, Szeliga KT, Jordan K, Grant KA. Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate ligands under different ethanol training conditions in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;162:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Helms CM, Grant KA. The effect of age on the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol and its GABA(A) receptor mediation in cynomolgus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:333–343. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2219-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Green KL, Azarov AV, Szeliga KT, Purdy RH, Grant KA. The influence of menstrual cycle phase on sensitivity to ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of GABA(A)-positive modulators. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:379–383. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Licata SC, Platt DM, Rüedi-Bettschen D, Atack JR, Dawson GR, Van Linn ML, Cook JM, Rowlett JK. Discriminative stimulus effects of L-838,417 (7-tert-butyl-3-(2,5-difluoro-phenyl)-6-(2-methyl-2H-[1,2,4]triazol-3-ylmethoxy)-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-b]pyridazine): role of GABA(A) receptor subtypes. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Platt DM, Duggan A, Spealman RD, Cook JM, Li X, Yin W, Rowlett JK. Contribution of alpha 1GABAA and alpha 5GABAA receptor subtypes to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:658–667. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.080275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Helms CM, Rogers LS, Waters CA, Grant KA. Zolpidem generalization and antagonism in male and female cynomolgus monkeys trained to discriminate 1.0 or 2.0 g/kg ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1197–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grant KA, Azarov A, Bowen CA, Mirkis S, Purdy RH. Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of the neurosteroid 3 alpha-hydroxy-5 alpha-pregnan-20-one in female Macaca fascicularis monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:340–346. doi: 10.1007/BF02247439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grant KA, Azarov A, Shively CA, Purdy RH. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol and 3 alpha-hydroxy-5 alpha-pregnan-20-one in relation to menstrual cycle phase in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s002130050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Selectivity in the generalization profile in baboons trained to discriminate lorazepam: benzodiazepines, barbiturates and other sedative/anxiolytics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:1442–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Massey BW, Woolverton WL. Discriminative stimulus effects of combinations of pentobarbital and ethanol in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;35:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McMahon LR, France CP. Combined discriminative stimulus effects of midazolam with other positive GABAA modulators and GABAA receptor agonists in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;178:400–409. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Platt DM, Bano KM. Opioid receptors and the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in squirrel monkeys: mu and delta opioid receptor mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;650:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Duka T, Stephens DN, Russel C, Tasker R. Discriminative stimulus properties of low doses of ethanol in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;136:379–389. doi: 10.1007/s002130050581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Duka T, Jackson A, Smith DC, Stephens DN. Relationship of components of an alcohol interoceptive stimulus to induction of desire for alcohol in social drinkers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jackson A, Stephens D, Duka T. A low dose alcohol drug discrimination in social drinkers: relationship with subjective effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;157:411–420. doi: 10.1007/s002130100817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jackson A, Stephens D, Duka T. Gender differences in response to lorazepam in a human drug discrimination study. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:614–619. doi: 10.1177/0269881105056659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kelly TH, Stoops TH, Perry AS, Prendergast MA, Rush CR. Clinical neuropharmacology of drugs of abuse: a comparison of drug-discrimination and subject-report measures. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev. 1997;2:227–260. doi: 10.1177/1534582303262095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Perkins K. Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in humans. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;192:369–400. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hodge CW, Aiken AS. Discriminative stimulus function of ethanol: role of GABAA receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1221–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hodge CW, Nannini MA, Olive MF, Kelley SP, Mehmert KK. Allopregnanolone and pentobarbital infused into the nucleus accumbens substitute for the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1441–1447. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hodge CW, Cox AA. The discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol are mediated by NMDA and GABA(A) receptors in specific limbic brain regions. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;139:95–107. doi: 10.1007/s002130050694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nie Z, Madamba SG, Siggins GR. Ethanol inhibits glutamatergic neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens neurons by multiple mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1566–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nie Z, Madamba SG, Siggins GR. Ethanol enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid responses in a subpopulation of nucleus accumbens neurons: role of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:654–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Besheer J, Schroeder JP, Stevenson RA, Hodge CW. Ethanol-induced alterations of c-Fos immunoreactivity in specific limbic brain regions following ethanol discrimination training. Brain Res. 2008;1232:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jaramillo AA, Randall PA, Frisbee S, Besheer J. Modulation of sensitivity to alcohol by cortical and thalamic brain regions. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;44:2569–2580. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Besheer J, Cox AA, Hodge CW. Coregulation of ethanol discrimination by the nucleus accumbens and amygdala. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:450–456. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057036.64169.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]