Abstract

Recently the TaMYC1 gene encoding bHLH transcription factor has been isolated from the bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genome and shown to co-locate with the Pp3 gene conferring purple pericarp color. As a functional evidence of TaMYC1 and Pp3 being the same, higher transcriptional activity of the TaMYC1 gene in colored pericarp compared to uncolored one has been demonstrated. In the current study, we present additional strong evidences of TaMYC1 to be a synonym of Pp3. Furthermore, we have found differences between dominant and recessive Pp3(TaMyc1) alleles. Light enhancement of TaMYC1 transcription was paralleled with increased AP accumulation only in purple-grain wheat. Coexpression of TaMYC1 and the maize MYB TF gene ZmC1 induced AP accumulation in the coleoptile of white-grain wheat. Suppression of TaMYC1 significantly reduced AP content in purple grains. Two distinct TaMYC1 alleles (TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w) were isolated from purple- and white-grained wheat, respectively. A unique, compound cis-acting regulatory element had six copies in the promoter of TaMYC1p, but was present only once in TaMYC1w. Analysis of recombinant inbred lines showed that TaMYC1p was necessary but not sufficient for AP accumulation in the pericarp tissues. Examination of larger sets of germplasm lines indicated that the evolution of purple pericarp in tetraploid wheat was accompanied by the presence of TaMYC1p. Our findings may promote more systematic basic and applied studies of anthocyanins in common wheat and related Triticeae crops.

Keywords: common wheat, purple pericarp, anthocyanin biosynthesis, bHLH transcription factor, Pp3

Introduction

Anthocyanin pigments (APs) constitute an important class of secondary metabolites synthesized by most plants. They are responsible for the pigmentation of different types of plant organs, and function as attractors for the vectors of pollens and seeds (Joaquin-Cruz et al., 2015). APs have been found to participate in non-specific disease resistance and the protection against biotic and abiotic stresses in plants (Treutter, 2006). Consequently, adverse environmental factors, such as high light, low temperature, high salinity, and/or drought stress, generally induce AP accumulation (Jayalakshmi et al., 2012). In recent years, anthocyanins have attracted wide attention owing to their anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-bacterial effects (Mazza, 2007; Wang and Stoner, 2008; Bowen-Forbes et al., 2010). In common wheat (Triticum aestivum, 2n = 6x = 42, AABBDD) and durum wheat (T. turgidum ssp. durum, 2n = 4x = 28, AABB) crops, APs accumulated in the grains represent a valuable source of dietary bioactive materials in the functional food industry (Li et al., 2007; Khlestkina et al., 2011; Revanappa and Salimath, 2011).

Anthocyanin biosynthesis and metabolic pathways have been studied in many plant species. The main structural genes for anthocyanin biosynthesis encode phenylalanine ammonia lyase, chalcone synthase, chalcone isomerase, flavanone 3-hydroxylase, flavonoid 3-hydroxylase, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase, leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase, and flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (Holton and Cornish, 1995). Two major classes of transcription factors (TFs), MYB and basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), have been found to regulate the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes (Zhang et al., 2014). Allelic variations of a number of MYB and bHLH TFs have been linked with differential accumulations of APs in different plant organs (Zhang et al., 2014). The MYB TF ZmC1 is well-known for its role in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in maize (McClintock, 1950; Pazares et al., 1987). DNA sequence variation in the promoter region of a functional MYB TF gene, VvmybA1, leads to changes in the flesh pigment content of grapes (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Porret et al., 2006; This et al., 2007). Similar MYB regulators have also been characterized in Arabidopsis (PAP1 and PAP2) (Borevitz et al., 2000), petunia (MYB3) (Solano et al., 1995), and sweet potato (MYB10) (Feng et al., 2010). The bHLH TFs affecting anthocyanin biosynthesis have also been identified in multiple plant species. In maize, the bHLH TFs, R, B, Sn, and Hopi, regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in specific tissues, including the aleurone layer, scutellum, pericarp, root, mesocotyl, leaf, and anther (Styles et al., 1973; Tonelli et al., 1991; Goff et al., 1992; Procissi et al., 1997; Petroni et al., 2000). In rice, a mutation in the bHLH domain of the RC protein is responsible for the white pericarp phenotype of the grain (Sweeney et al., 2006). Homologs of the maize R and B TFs controlling anthocyanin biosynthesis in specific tissues are also known in Antirrhinum (Delila) (Carpenter et al., 1991), petunia (Jaf13) (Quattrocchio et al., 1998), tomato (AH) (Qiu et al., 2016), and Ipomoea purpurea (bHLH2) (Park et al., 2007).

AP accumulation has frequently been found in many colored wheat tissues/organs, such as purple leaf blade, purple culm, purple glume, purple anther, purple pericarp, red coleoptile, red auricle, and red grain (Tereshchenko et al., 2013). These color traits have traditionally been used as visual markers for genetic analysis (Zeven, 1991). But in recent years there are increasing interests in developing the wheat cultivars with colored grains for manufacturing functional foods (Li et al., 2007; Khlestkina et al., 2011; Revanappa and Salimath, 2011). The molecular genetic basis controlling tissue/organ-specific accumulation of APs in wheat has been investigated by several studies. Two MYB TFs, R, and Rc, are found involved in the regulation of proanthocyanidin synthesis in wheat grains and coleoptiles (Himi et al., 2011; Himi and Taketa, 2015; Wang Y. Q. et al., 2016). Some insights have also been gained into the MYB and bHLH TFs controlling AP biosynthesis in purple pericarp, which is the main site of AP accumulation in purple wheat grains. Classic genetic analysis indicates that the homoeoallelic Pp1 genes on the short arms of group 7 chromosomes and the Pp3 gene on chromosome arm 2AL of common wheat control red pericarp (Knievel et al., 2009). Subsequent investigations suggest that Pp1 may be orthologous to ZmC1 of maize and OsC1 of rice, which encode MYB-like TFs responsible for the activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes (Saitoh et al., 2004; Khlestkina, 2013). Recently, a genetic analysis proposed that TaMYC1, a putative wheat MYC TF gene, may be Pp3, based on co-location of TaMYC1 with the Pp3 gene conferring purple pericarp color and the transcript level of the dominant TaMYC1 allele being much higher in purple pericarp tissues as a functional evidence (Shoeva et al., 2014). In our expression profile analysis, we also observed that the expression level of TaMYC1 was higher in purple wheat grains than in white wheat grains (Liu et al., 2016). Nevertheless, there is still no strong molecular genetic evidence supporting the function of TaMYC1 in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in purple wheat grains. Furthermore, it is not known if the TaMYC1 alleles in purple and white pericarp tissues may differ in structure and function.

Based on the information above, the main objectives of this work were to examine if TaMYC1 may regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in purple pericarp and to characterize the TaMYC1 alleles from purple- and white-grained wheat, respectively. By combining molecular and genetic investigations, we found that manipulation of TaMYC1 expression directly affected anthocyanin biosynthesis. We isolated two TaMYC1 alleles, TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w, from purple- and white-grained wheat cultivars, respectively, and found that their promoter regions differed substantially. These functional verification and association analysis data lead us to suggest that TaMYC1 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in the purple pericarp tissues of common wheat, and that TaMYC1p represents a novel bHLH TF gene allele.

Results

Molecular characteristics of TaMYC1

Previous studies indicated that TaMYC1 was located on 2AL (Shoeva et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Based on the information reported in these studies, we designed further experiments to investigate the molecular characteristics of TaMYC1. The genomic and cDNA sequences of TaMYC1 were isolated from the common wheat cultivars Gaoyuan 115 (purple-grained) and Opata (white-grained), respectively. The genomic region containing the TaMYC1 open reading frame (ORF) was found to be 4,584 bp in both Gaoyuan 115 and Opata.

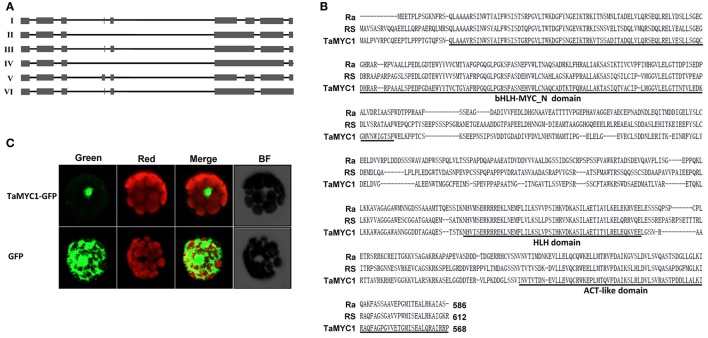

Sequencing TaMYC1 cDNAs amplified from Gaoyuan 115 grain tissues identified six different transcript isoforms (Isoforms I–VI, Figure 1A), with Isoform III accounting for ~86.6% of the total transcripts (Table S1). The ORF size of the six isoforms varied from 1,566 to 1,798 bp (Table S1), and the number of exons covered by them differed from five to nine (Figure 1A). The genomic ORF of TaMYC1 in Opata was identical to that of Gaoyuan 115. The six transcript isoforms of TaMYC1 were also found in the grain tissues of Opata, though in this cultivar the transcript level of TaMYC1 was much lower (see below).

Figure 1.

Molecular analysis of TaMYC1 transcripts and deduced protein. (A) The six transcript isoforms (I–VI) identified for TaMYC1. The number of exons (represented by filled boxes) covered by the six isoforms varied from five (Isoform IV) to nine (Isoform V). (B) Amino acid sequence comparison between TaMYC1 (deduced from Isoform III) and two representative bHLH regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis, RS from maize and Ra from rice. The three domains (bHLH-MYC_N domain, HLH domain and ACT-like domain) conserved among known bHLH TFs regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis are underlined. The GenBank accession numbers of the three sequences are NP_001106073 (RS), AAC49219 (Ra), or KX867111 (TaMYC1). (C) Localization of TaMYC1-GFP fusion protein in the nucleus of Arabidopsis protoplast. As a control, the free GFP protein was distributed throughout the cytoplasm of the protoplast. The images shown were taken under a confocal microscope using green (for GFP fluorescence) or red (for chlorophyll fluorescence) filters or under bright field (BF). The merged images depicted more clearly the relative positions of GFP and chlorophyll fluorescence in the photographed protoplasts.

Conceptual translation of the six isoforms yielded polypeptides containing 407–580 amino acids (Table S1). However, only the deduced protein of Isoform III contained all three domains (bHLH-MYC_N, HLH, and ACT-like) shared by the MYC TFs previously found involved in controlling AP biosynthesis (Figure 1B, Figure S1). On the other hand, the translated product of Isoform I had 47 amino acids deleted in the HLH domain; a stretch of 24 residues were deleted in the bHLH-MYC_N domain in the polypeptide derived from Isoform II; the deduced product of Isoform IV had 24 amino acids deleted in the bHLH-MYC_N domain and an insertion of “TRTRTPPKSKRKEKKYstop” in the HLH domain; the deduced polypeptide of Isoform V had an insertion of “GAHACYLCRLNQ” in the ACT-like domain; an insertion of “VWEstop” in the ACT-like domain was found for the polypeptide translated from Isoform VI (Figure S1).

A TaMYC1 (Isoform III)-GFP fusion cistron, directed by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, was constructed and transiently expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts. The results showed that the TaMYC1-GFP fusion protein was located in the nucleus, whereas the control GFP protein was distributed throughout the cell (Figure 1C).

Expression analysis of TaMYC1

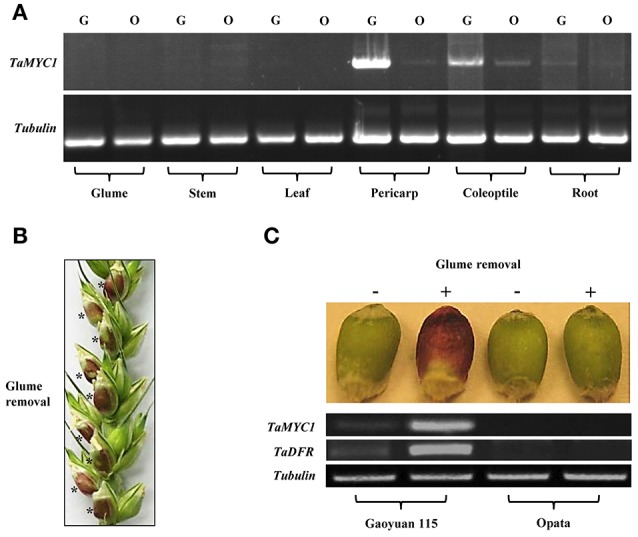

The transcriptional behavior of TaMYC1 in several different tissues of Gaoyuan 115 and Opata was investigated by semi-quantitative PCR with a pair of primers capable of recognizing all six transcript isoforms. As shown in Figure 2A, for both cultivars, the transcript level of TaMYC1 was highest in pericarp tissues, intermediate in coleoptile and root tissues, and undetectable in leaf, stem, and glume tissues. But notably, TaMYC1 transcripts were substantially more abundant in the pericarp, coleoptile, and root cells of Gaoyuan 115 than in those of Opata (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Transcriptional characteristics of TaMYC1. (A) Relative transcript levels of TaMYC1 in the different organs/tissues (glume, stem, leaf, pericarp, coleoptile, and root) of Gaoyuan 115 (G) and Opata (O) as assessed using semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The amplification of wheat tubulin gene served as an internal control. (B) Artificial removal of outer and inner glumes induced purple AP accumulation in the developing grains of Gaoyuan 115. Glume removal was conducted at 14 days after flowering, with AP induction becoming visible in the grains (indicated by asterisks) 2 days after the treatment. (C) Relative transcript levels of TaMYC1 and TaDFR in the grains of Gaoyuan 115 and Opata without (−) or with (+) glume removal treatment. The transcript levels were evaluated using semi-quantitative RT-PCR with the amplification of wheat tubulin gene as an internal control. The data displayed are representative of three separate tests.

Past studies have shown that artificial light exposure can stimulate AP accumulation in plant organs (Singh et al., 1999; Takos and Walker, 2006; Meng and Liu, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). Therefore, we tested the effects of removing outer and inner glumes on AP accumulation and TaMYC1 transcription in developing wheat grains. At 14 days after flowering (DAF), the glumes were carefully removed for one of the developing grains in a selected spikelet, with the glumes of the remaining grains retained as experimental controls (Figure 2B). Two days after the treatment, conspicuous purple AP accumulation was observed in the grains without glumes but not in the control ones with glume coverage in Gaoyuan 115 (Figure 2C). However, in Opata, no purple AP accumulation was found in either the grains with glume removal or the control ones (Figure 2C). The transcript level of TaMYC1 was substantially up-regulated in the Gaoyuan 115 grains with glume removal, which was paralleled by a strong increase in the transcripts of TaDFR, an important anthocyanin biosynthesis gene coding for the enzyme dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (Figure 2C). Neither TaMYC1 nor TaDFR were transcriptionally up-regulated in the grains of Opata irrespective of glume removal or retention (Figure 2C).

Induction of purple AP accumulation by overexpression of TaMYC1 and ZmC1

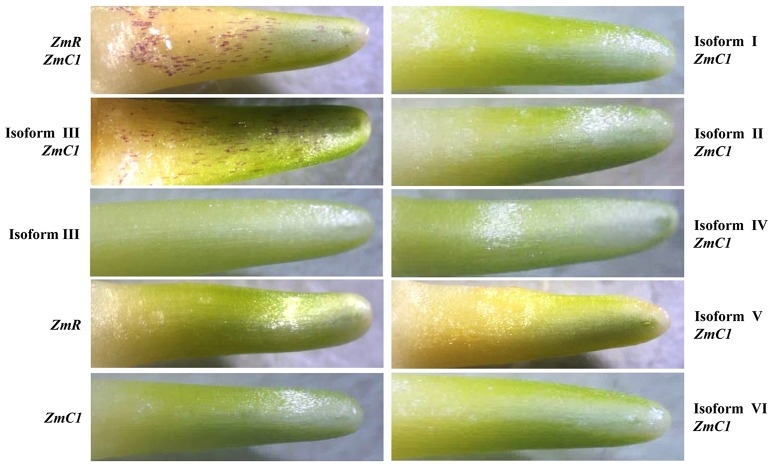

In previous research on maize anthocyanin regulators, coexpression of ZmC1 (encoding a MYB TF) and ZmR (coding for a bHLH TF) was shown to be sufficient for inducing AP accumulation (Ludwig et al., 1989). Therefore, in this work, we tested if overexpression of TaMYC1 and ZmC1 may confer anthocyanin biosynthesis. The six transcript isoforms of TaMYC1 was individually coexpressed with ZmC1 in wheat coleoptile cells via particle bombardment mediated gene transfer (see Methods). As anticipated, simultaneous expression of ZmC1 and ZmR conferred strong AP accumulation in the bombarded cells (Figure 3). Among the six transcript isoforms of TaMYC1, only Isoform III induced AP accumulation when coexpressed with ZmC1 (Figure 3). On the other hand, expression of ZmC1, ZmR, or Isoform III alone failed to induce AP accumulation in the bombarded cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis by TaMYC1 in combination with ZmC1. The expression constructs of ZmC1, ZmR, and the six transcript isoforms of TaMYC1 (Isoforms I–VI) were delivered into the coleoptile cells of the white-grain wheat Opata with particle bombardment in appropriate combinations or singularly. The presence of red colored cells in the bombarded coleoptiles indicates induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Of the six different types of transcripts of TaMYC1, only Isoform III induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in combination with ZmC1. The results shown are typical of three independent assays.

Silencing TaMYC1 expression inhibited purple AP accumulation in gaoyuan 115 grains

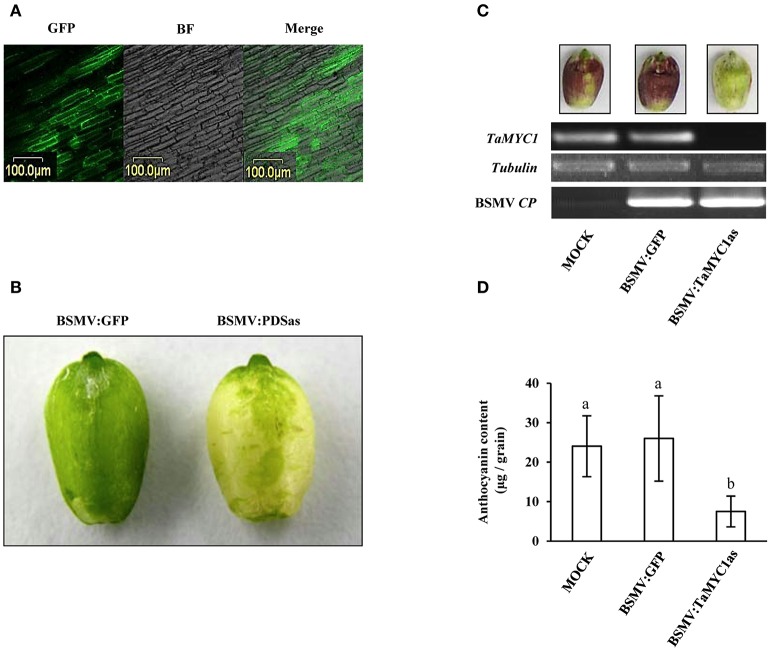

From the data present above, it became necessary to investigate if decreasing the expression of TaMYC1 may reduce AP accumulation in purple-grained wheat. A virus induced gene silencing (VIGS) approach mediated by barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV) was adopted for decreasing TaMYC1 expression, because BSMV-VIGS has frequently been employed for functional studies of wheat genes (Wang et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). Three recombinant BSMVs, including BSMV:GFP, BSMV:PDSas and BSMV:TaMYC1as, were used in this experiment. BSMV:GFP, expressing the green fluorescence protein (GFP) (Wang et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011), was used to monitor virus spread in the inoculated wheat plants. BSMV:PDSas, silencing wheat phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene and resulting photo bleaching (Scofield et al., 2005; Puri et al., 2007), provided a visual indication of positive gene silencing. BSMV:TaMYC1as was prepared in this work to silence TaMYC1 expression in developing wheat grains.

The three viruses were each introduced into Gaoyuan 115 plants through transcript inoculation of young flag leaves, with the buffer inoculated plants as mock controls (see Methods). The treated plants flowered at ~2.5 weeks post-inoculation. At 14 DAF, GFP fluorescence was detected in the pericarp cells of the plants inoculated by BSMV:GFP (Figure 4A). Photo bleaching was observed on the grains collected from the plants inoculated with BSMV:PDSas but not on those from the mock controls (Figure 4B). The grains in the BSMV:TaMYC1as plants did not show photo bleaching either. After glume removal and exposure to light, purple anthocyanins were strongly accumulated in the grains of mock controls and the plants infected by BSMV:GFP but not in those infected by BSMV:TaMYC1as (Figure 4C). In agreement this finding, TaMYC1 transcripts were found in the grains of mock controls and the plants infected by BSMV:GFP, but not detected by RT-PCR in the grains of the plants infected by BSMV:TaMYC1as (Figure 4C). Lastly, successful infection of the developing grains by BSMV:GFP or BSMV:PDSas was confirmed by positive detection of viral CP transcripts (Figure 4C). Quantitative measurement showed that the mean anthocyanin content of BSMV:TaMYC1as infected grains was reduced by 69.2% relative to that of BSMV:GFP infected grains, while there was no significant difference in this parameter between BSMV:GFP infected grains and those of mock controls (Figure 4D, Table S2).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the function of TaMYC1 in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis using virus induced gene silencing. Three recombinant barley stripe mosaic viruses (BSMV:GFP, BSMV:PDSas, and BSMV:TaMYC1as) were used in this experiment. Wheat plants (cv Gaoyuan 115) were inoculated with the three viruses, respectively. The developing grains were used for the experiment 14 days after the flowering. (A) GFP fluorescence was detected in the developing grains of the plants infected by BSMV:GFP. The images shown were taken under a confocal microscope in GFP channel and bright field (BF), respectively, followed by merging. (B) Photo bleaching was observed in the developing grains of the plants infected by BSMV:PDSas because of silencing the expression of phytoene desaturase gene. The bleaching phenotype did not occur in the developing grains of the plants infected by BSMV:GFP. (C) Evaluation of the relative transcript levels of TaMYC1 and BSMV CP gene in the developing grains of mock controls and the plants infected by BSMV:GFP or BSMV:PDSas. The grains were subjected to glume removal, and at 2 days after the treatment, they were collected for this analysis. Purple anthocyanin pigments were induced in the grains of mock controls and the plants infected by BSMV:GFP but not those infected by BSMV:TaMYC1as. Consistent with this finding, TaMYC1 transcripts accumulated in the grains of mock controls and the plants infected by BSMV:GFP, but were undetectable by RT-PCR in the grains of the plants infected by BSMV:TaMYC1as. Successful infection of the developing grains by BSMV:GFP or BSMV:PDSas was confirmed by positive detection of viral CP transcripts. The results depicted are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Comparison of anthocyanin contents among the developing grains of mock controls and the plants infected by BSMV:GFP or BSMV:TaMYC1as. The three sources of grains, as shown in (C), were individually assayed for anthocyanin content, with the averaged values (means ± SE, n = 20) being compared statistically. The means marked by different letters are statistically significant (P < 0.05). The data shown were reproducible in another two separate determinations.

Sequence analysis of TaMYC1P and TaMYC1W alleles

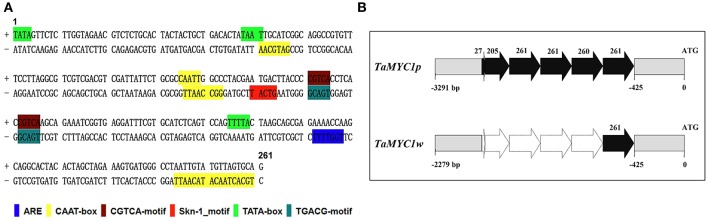

The 5′ proximal region of TaMYC1 was isolated from both Gaoyuan 115 and Opata. It was found to be 3,291 bp in Gaoyuan 115 and 2,279 bp in Opata. Analysis of the resultant sequences identified a repeated sequence element of 261 nucleotides (nts), which had three prefect (261 nts), one nearly intact (260 nts), and two incomplete copies (27 and 205 nts, respectively) in the promoter of the TaMYC1 allele in Gaoyuan 115 (designated as TaMYC1p), but was present only once (261 nts) in the corresponding region of the TaMYC1 allele in Opata (designated as TaMYC1w) (Figures 5A,B). By analysis with the software PlantCARE, this 261 nt element was found to contain 16 copies of previously identified cis-acting regulatory motifs (boxes), including one ARE motif, eight CAAT boxes, two CGTCA motifs, one Skn-1 motif, three TATA boxes, and one TGACG motif (Figure 5A, Table S3). Interestingly, this putative, compound cis-acting regulatory element had not been identified and characterized by past studies. Searching public nucleic acid and genomic databases indicated that it was present exclusively in the promoter region of predicted bHLH TF genes in Triticeae species (Table S4). However, in these predicted bHLH TF genes, the copy number of the 261 nt element was generally ≤ 2 (Table S4), which was much fewer than that found in the promoter region of TaMYC1p (Figure 5). Together, the results above indicated that TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w alleles differed strongly in the promoter region, despite that they had an identical coding sequence.

Figure 5.

Bioinformatic analysis of a putative, 261 nt cis-regulatory element in the promoter region of TaMYC1. (A) Presence of multiple cis-acting regulatory motifs (boxes) in the 261 nt element as predicted using the PlantCARE software. (B) A diagram illustrating copy number difference of the 261 nt element in the promoter regions of two TaMYC1 alleles (TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w) isolated from purple- and white-grained wheat cultivars, respectively. The 261 nt element had three perfect (261 nts), one nearly intact (260 nts) and two partial (27 or 205 nts) copies in the promoter of TaMYC1p, but was present only once (261 nts) in the corresponding region of TaMYC1w. ATG indicates the start codon of the coding sequence.

Segregation of pericarp colors and TaMYC1 alleles in a RIL population

A polymorphic PCR marker, Xtamyc1, was designed based on nucleotide sequence difference between the promoter regions of TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w. The amplicons yielded by Xtamyc1 were either 2,163 bp (for TaMYC1p) or 1,151 bp (for TaMYC1w) (Figure S2). A total of 185 RILs developed using Gaoyuan 115 and Opata as parents were examined for pericarp colors. The numbers of RILs with purple or white pericarp were 55 and 130, respectively (Table 1). When screened using Xtamyc1, the 55 purple-grained RILs all carried TaMYC1p, but for the 130 white-grained RILs, 90 had TaMYC1w, and the remaining 40 carried TaMYC1p (Table 1).

Table 1.

Segregation of pericarp colors and TaMYC1 alleles in the RILs derived from the cross between Gaoyuan 115 and Opata.

| Pericarp color | TaMYC1 allele | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaMYC1p | TaMYC1w | ||

| Purple | 55 | 0 | 55 |

| White | 40 | 90 | 130 |

| Total | 95 | 90 | 185 |

Association between purple pericarp color and TaMYC1P allele in diploid, tetraploid, and common wheat germplasm materials

It is well-known that common wheat was evolved through two polyploidization events (Nesbitt, 2001). The first one involved the diploid wheat T. urartu (AA, 2n = 2x = 14) and an Aegilops species (carrying the B genome), and formed tetraploid wheat (AABB, 2n = 4x = 28). The second one occurred between tetraploid wheat and the diploid goatgrass Ae. tauschii (DD, 2n = 2x = 14), and resulted in common wheat. Consequently, the A and D subgenomes of common wheat were donated by T. urartu and Ae. tauschii, respectively, and tetraploid wheat played an essential role in the evolution of common wheat. Both T. urartu and tetraploid wheat have many genetically different forms, which are important germplasm materials for wheat genetic, evolutionary and breeding studies (Salamini et al., 2002). Based on the above information, we investigated the allelic status of TaMYC1 in multiple lines of T. urartu, tetraploid wheat and common wheat using Xtamyc1 marker in order to explore potential association between purple pericarp color and TaMYC1p allele in wheat germplasm materials (Table 2). Because it has been suggested that purple pericarp in common wheat may be originally derived from tetraploid wheat (Zeven, 1991), we included three species of tetraploid wheat and relatively more purple-grained tetraploid wheat lines in this analysis (Table 2). The 98 T. urartu accessions all had white pericarp, and they were all found to carry TaMYC1w. Among the 256 durum wheat lines, 236 had purple pericarp and carried TaMYC1p; the remaining 20 lines had white pericarp and possessed TaMYC1w. For another two tetraploid wheat species (T. turgidum ssp. turgidum and T. turgidum ssp. polonicum), the 12 purple-grained lines were all found to host TaMYC1p, whereas the 20 white-grained lines all carried TaMYC1w. Of the 102 common wheat lines, 14 had purple pericarp and possessed TaMYC1p; 88 were white-grained with only TaMYC1w detected in them (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between pericarp colors and TaMYC1 alleles in diploid, tetraploid, and hexaploid wheat germplasm lines.

| Genome | Species | Pericarp color | Number of lines | TaMYC1 allele | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaMYC1p | TaMYC1w | ||||

| AA (Diploid) | T. urartu | White | 98 | 0 | 98 |

| AABB (Tetraploid) | T. turgidum ssp. durum | Purple | 236 | 236 | 0 |

| White | 20 | 0 | 20 | ||

| T. turgidum ssp. polonicum | Purple | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| White | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| T. turgidum ssp. turgidum | Purple | 10 | 10 | 0 | |

| White | 17 | 0 | 17 | ||

| AABBDD (Hexaploid) | T. aestivum | White | 88 | 0 | 88 |

| Purple | 14 | 14 | 0 | ||

| Total | 488 | 262 | 226 | ||

Discussion

In this work, we investigated the function of TaMYC1 in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis, and isolated two different alleles of TaMYC1 from purple- and white-grained wheat, respectively. The new insights obtained and their implications for further research are discussed below.

TaMYC1 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis

Prior to this work, TaMYC1 had been implicated in the control of purple pericarp in wheat (Shoeva et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016), although no strong molecular evidence was available for its function in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Here, we obtained complementary molecular and genetic evidence for the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by TaMYC1. First, TaMYC1 encoded a bHLH protein that was targeted to plant nucleus, and homologous to the bHLH TFs (e.g., Ra and RS) known to be involved in the control of anthocyanin biosynthesis (Figure 1). Second, the transcript level of TaMYC1 was substantially higher in purple pericarp tissues relative to white pericarp tissues (Figure 2A), which consistent with earlier studies (Shoeva et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Our result was based on the transcript comparison of TaMYC1 between the white grain cultivar Opata and the purple grain cultivar Gy115, while the earlier study was carried out in NILs (Liu et al., 2016). Furthermore, our glume removal experiment showed clearly a parallel between light enhanced transcription of TaMYC1 and increased accumulation of purple APs in the pericarp tissues of purple-grained, but not white-grained, wheat (Figure 2B). Third, simultaneous overexpression of TaMYC1 and ZmC1 mimicked the effects of coexpression of ZmR and ZmC1, both of which are validated regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis (Pazares et al., 1987; Ludwig et al., 1989), on the induction of purple AP accumulation in wheat coleoptile cells (Figure 3). Lastly, decreasing the transcript level of TaMYC1 through VIGS inhibited the accumulation of APs, and dramatically reduced anthocyanin content in a purple-grained wheat cultivar (Figure 4). Collectively, the above evidence suggests that (1) TaMYC1 is a functional analog of ZmR in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in plant cells, (2) TaMYC1, with a relatively higher transcript level in the purple pericarp tissues, is necessary for AP accumulation in purple-grained wheat, and (3) The lower transcript level of TaMYC1 in the white pericarp tissues may contribute to the lack of AP accumulation in white-grained wheat. Nevertheless, the higher expression level of TaMYC1 is unlikely the solely promoter of anthocyanin accumulation in the purple pericarp tissues of Gaoyuan 115; the lower expression level of TaMYC1 may not be the only reason for the lack of anthocyanin accumulation in the white pericarp tissues of Opata. By analogous to previous studies (Khlestkina, 2013; Tereshchenko et al., 2013; Shoeva et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016), a MYB TF gene is required for the promotion of anthocyanin accumulation by TaMYC1 (see also below). This MYB TF gene should be functional in Gaoyuan 115 grains. Further study is required to isolate this gene and to examine its functional interaction with TaMYC1.

Although TaMYC1 had multiple transcript isoforms (Figure 1A), the dominant isoform (Isoform III) accounted for more than 80% of the transcripts, and encoded a functional bHLH protein capable of promoting AP accumulation in wheat coleoptile cells with the aid of ZmC1 (Figure 3). Unlike Isoform III, the other minor transcript isoforms could not cause AP accumulation when coexpressed with ZmC1 (Figure 3). These results, plus the observation that an identical set of TaMYC1 transcript isoforms was present in both purple and white pericarp tissues, indicate that the minor transcript isoforms may not play a significant role in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by TaMYC1. However, more efforts are needed to investigate if there might be additional and functional transcript isoforms of TaMYC1 in the pericarp tissues.

It is interesting to note that a low level of TaMYC1 transcripts was also present in the root tissues of Gaoyuan 115 and Opata (Figure 2A), although no purple anthocyanin pigments were visible in this organ. One possibility is that TaMYC1 may be involved in the activation of flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in the roots, but the function of this pathway does not result in purple anthocyanin pigments in the root tissues owing to the lack of other gene(s). In line with this possibility, previous studies have shown that flavonoid biosynthesis pathway is active, and various flavonoid compounds are accumulated, in the roots of many plant species (Buer et al., 2006; Hernández-Mata et al., 2010; Wang H. et al., 2016).

TaMYC1p represents a novel BHLH TF gene allele

Aside from confirming the function of TaMYC1 in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis, this work identified two distinct alleles of TaMYC1 (i.e., TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w) from purple- and white-grained wheat, respectively. Interestingly, among the RILs segregating for pericarp color, purple pericarp co-segregated with TaMYC1p, but TaMYC1p was not strictly linked with purple pericarp (Table 1). This indicates that in the examined RIL population TaMYC1p is necessary but not sufficient for conferring purple pericarp. This may not be surprising considering that multiple TF genes (e.g., MYB and bHLH TF genes) have been found to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants (Zhang et al., 2014). Additionally, molecular variations in the structural genes of anthocyanin biosynthesis can also affect AP accumulation in plant organs (Kim et al., 2009; Ho and Smith, 2016). It is possible that the white-grained parent (i.e., Opata) lacks not only a functional TaMYC1 allele but also additional genetic determinant(s) required for AP accumulation (e.g., a MYB TF gene). In this context, the RILs carrying TaMYC1p but with different pericarp colors are useful for identifying the additional genetic determinant(s) functioning in AP accumulation in further research.

TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w differed clearly in the promoter region with respect to the copy number of the 261 nt element (Figure 5). This putative, complex cis-acting regulatory element was present in multiple copies (three perfect and three partial) in the promoter region of TaMYC1p but only once in that of TaMYC1w. The homologs of the 261 nt element existed in only Triticeae species (barley, wheat, and related species), and were present exclusively in the promoter region of predicted bHLH TF genes (Table S4). Moreover, the homologous elements were present generally in low copy numbers (≤ 2) in the promoter region of these bHLH TF genes (Table S4). Thus, presence of multiple intact copies (≥3) of the 261 nt element in the promoter region was not found in any of the previously identified genes involved in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis; it is unique for TaMYC1p, and makes this allele a novel genetic variant capable of enhancing AP accumulation in the purple pericarp of wheat. Since TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w did not differ in the coding sequence, it is tempting to suggest that variation in the copy number of the 261 nt element in the promoter region may be responsible for the functional difference between TaMYC1p and TaMYC1w in regulating AP accumulation in the pericarp. We are now in the process of testing this possibility.

Origin of TaMYC1p in wheat

Previous genetic studies have suggested that purple pericarp is absent in diploid wheat, and that this trait may have evolved in the tetraploid wheat populations (Zeven, 1991). In this work, neither purple pericarp nor TaMYC1p allele were observed in the diploid wheat T. urartu, but purple pericarp was readily found in three species of tetraploid wheat examined, and all of the examined varieties with purple pericarp harbored TaMYC1p (Table 2). Our findings are consistent with the suggestions made by past studies on purple pericarp in wheat and closely related species, and further point out that the evolution of purple pericarp in tetraploid wheat is caused by the differentiation of TaMYC1p allele. Remarkably, TaMYC1p was present in all 15 purple-grained common wheat lines examined in this work. This indicates that the purple pericarp and TaMYC1p allele in these lines may be originally derived from tetraploid wheat through interspecific hybridization. However, the number of purple-grained common wheat lines investigated in this work is limited. Further study, involving the analysis of more diverse purple-grained common wheat materials, is needed to verify the above observation and speculation.

In summary, we generated convincing evidence for the function of TaMYC1 in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis in the pericarp tissues of common wheat. The novel TaMYC1 allele, TaMYC1p, is a necessary genetic determinant of purple pericarp in wheat. TaMYC1 and its alleles may aid further studies on the molecular mechanisms underlying anthocyanin biosynthesis and genetic enhancement of AP accumulation in wheat grains.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Two main sets of wheat materials were used in this work. The first set included the common wheat varieties Gaoyuan 115 and Opata and the 185 RILs (at F8 generation) derived from a cross between the two varieties (with Gaoyuan 115 as female parent). Gaoyuan 115 was a stable and homozygous cultivar with red coleoptile and purple grain (Liu et al., 2016). The RIL population segregating for pericarp colors was developed using the single seed descent method (Tee and Qualset, 1975). The second set contained the wheat germplasm materials used for investigating the association between pericarp colors and TaMYC1 alleles. These lines, including 98 accessions of T. urartu, 256 accessions of T. turgidum ssp. durum, 5 accessions of T. turgidum ssp. polonicum, 27 accessions of T. turgidum ssp. turgidum, and 102 accessions of T. aestivum (Table S5), were obtained from the National Plant Germplasm System of the US Department of Agriculture (http://www.ars-grin.gov/) and the Chinese Crop Germplasm Resource Center located in Xining, China.

Preparation of genomic DNA, total RNA, and cDNA samples

Genomic DNA was isolated from the desired wheat samples using 1 g of 10-day-old seedlings (Yan et al., 2002). The coleoptile, husk, root, leaf, stem, and pericarp samples were collected from wheat plants as described previously (Tereshchenko et al., 2013). Total RNA was extracted from ~0.5 g of desired wheat tissues using the Tiangen RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Company, Beijing, China). The synthesis of cDNA from total RNA was accomplished using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR and semi-quantitative PCR

PCR was conducted using the high-fidelity Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Beijing, China) under the following conditions: 2 min of denaturation at 98°C; 35 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 61°C, and 30 s at 72°C; followed by a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. The PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector plasmid (Promega Corporation, Madison, USA). The recombinant plasmids were then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α cells, with the positive clones sequenced commercially (Huada Gene, Shenzheng, China). All primers used in this study are listed in Table S6.

The semi-quantitative RT-PCR experiments in this work were conducted following a previous publication (Zhou et al., 2011). The amplification of wheat tubulin gene transcripts was used to normalize the cDNA contents of various reverse transcription mixtures before PCR, and to monitor the kinetics of thermo-amplification during PCR. The reproducibility of the transcriptional patterns revealed by semi-quantitative PCR was tested by at least three independent assays.

Glume removal treatment and response of TaMYC1 transcription to light

Gaoyuan 115 and Opata plants were grown in a greenhouse at 25°C (day)/20°C (night), with a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark. At 14 days after anthesis, both the outer and inner glumes were carefully removed from 9 to 10 grains using forceps, with the remaining grains in the same spike untreated as controls. Afterwards, the plants were maintained under the same growth conditions. At 2 days after glume removal, the light exposed grains and the controls were photographed, and then used for investigating the transcriptional response of TaMYC1 to light with semi-quantitative RT-PCR as described above.

Transient expression experiments

For investigating the nuclear localization of TaMYC1, an expression construct (p35S-TaMYC1-GFP) was prepared by cloning TaMYC1 coding region upstream of that of GFP in the plasmid p35S-GFP (Liu et al., 2006). The two constructs (p35S-TaMYC1-GFP and p35S-GFP) were each delivered into Arabidopsis protoplasts using polyethylene glycol as reported previously (Liu et al., 2006). After 18 h of culture at 25°C, the protoplasts were examined under a Leica TCS SP2 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany).

To test if TaMYC1 may promote anthocyanin biosynthesis in the presence of ZmR, the six transcript isoforms (I–VI) of TaMYC1 and the coding sequences of ZmR and ZmC1 were each cloned downstream of the ubiquitin gene promoter in the plasmid vector pBRACT214 (Soltész and Vágújfalvi, 2013), resulting in the expression constructs pUbi-TaMYC1-I, pUbi-TaMYC1-II, pUbi-TaMYC1-III, pUbi-TaMYC1-IV, pUbi-TaMYC1-V, pUbi-TaMYC1-VI, pUbi-ZmR, and pUbi-ZmC1. These constructs were introduced into the coleoptile cells of Opata in the desired combinations or individually using particle bombardment (Ahmed et al., 2003). The coleoptiles were examined for purple AP accumulation at 2 days after bombardment, with the photographs taken under a stereoscope (Leica Co., Oskar-Barnack-Straße, Germany).

Knocking down TaMYC1 transcript level by VIGS

Among the three recombinant BSMVs used in this work, BSMV:GFP and BSMV:PDSas were prepared previously (Wang et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011), whereas BSMV:TaMYC1as was newly constructed following the method detailed in our prior study (Wang et al., 2011). A 200 bp cDNA fragment of TaMYC1 was obtained by RT-PCR using the oligo nucleotide primers containing NheI sites (Table S6). This fragment replaced GFP coding sequence in the BSMV plasmid RNAγgammab:GFP, giving rise to RNAγgammab:TaMYC1as. The combination of RNAγgammab:TaMYC1as with the RNAα and RNAβ clones of BSMV formed BSMV:TaMYC1as. In vitro transcripts were prepared for the RNAα, RNAβ, and RNAγ clones of the three BSMVs, and inoculated onto the immature flag leaves of Gaoyuan 115 (Wang et al., 2011). Twenty plants were inoculated for each recombinant virus, and the same number of plants was buffered inoculated as mock controls. The inoculated plants were grown under normal greenhouse conditions (see above), with the developing grains used for the experiment 14 days after flowering. BSMV spread in the developing grains of the plants inoculated with BSMV:GFP was checked by examining GFP fluorescence under confocal microscope (see above). The progress of gene silencing was monitored through observing photo bleaching in the developing grains infected by BSMV:PDSas.

For assessing the transcript levels of TaMYC1 and BSMV CP and the effects of knocking down TaMYC1 on anthocyanin accumulation, glume removal was conducted for 240 grains in the mock control plants (80) and those infected by BSMV:GFP (80) or BSMV:TaMYC1as (80). Two days after glume removal, the light exposed grains were collected for subsequent analysis. Evaluation of the transcript levels of TaMYC1 and BSMV CP was carried out by semi-quantitative RT-PCR as outlined above. The anthocyanin content of each grain was measured using the method for determining the total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of plant juices and derivative products (AOAC Official Method 2005.02). For either the mock controls or the plants infected BSMV:GFP or BSMV:TaMYC1as, the assay of anthocyanin content was performed using three separate sets of grains (with 20 grains in each set). Statistical analyses of the data were performed using the software package SPSS for Windows 17. The method was UNIANOVA, and The POST-HOC was DUNCAN ALPHA (0.05).

Genotyping RILs with Xtamyc1

To distinguish TaMYC1p from TaMYC1w, the polymorphic PCR marker, Xtamyc1, was designed according to nucleotide sequence difference between the promoter regions of the two alleles. The primers of Xtamyc1 are listed in Table S6. The amplicons produced by Xtamyc1 were 2,163 bp for TaMYC1p and 1,151 bp for TaMYC1w (Figure S2). The templates for genotyping with Xtamyc1 were the genomic DNA samples of Gaoyuan 115, Opata, and derivative RILs extracted as above. The PCR conditions were also described as above, except that the extension time was changed to 2 min.

Bioinformatic analysis

The exons covered by the six transcript isoforms of TaMYC1 were analyzed using the Gene Structure Display Server (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/). Amino acid sequence alignment was generated using the Vector NTI 10 software (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Tandem Repeats Finder (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html) was used to identify repeats in the promoter region of TaMYC1. The cis-acting regulatory motifs (boxes) in the 261 nt element were predicted with the PlantCARE software (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). Finally, the oligonucleotide primers used in this study were designed with the aid of Primer 5 software (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Additional information

Accession codes: The genomic sequences of TaMYC1 from Gaoyuan 115 and Opata had been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers KX867111 and KX867112, respectively. The sequences of the six transcript isoforms of TaMYC1 from Gaoyuan 115 were also submitted to GenBank with the accession numbers being KY499898–KY499903.

Author contributions

HZ, BL, and DW designed the research. YZ, XX, and SL performed the experiments. WC and BZ contributed reagents and greenhouse facility to the work. YZ, XX, SL, BL, DL, and HZ analyzed the data. BL, DW, HZ, and YZ wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFD0100500), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA08030106), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31071417, 31260322), the Project of Qinghai Science & Technology Department (2016-ZJ-Y01), the West Light Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Plateau Ecology and Agriculture, Qinghai University (2017-KF-06). We thank Professor Hongjie Li (Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for constructive comments on our research.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01645/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ahmed N., Maekawa M., Utsugi S., Himi E., Ablet H., Rikiishi K., et al. (2003). Transient expression of anthocyanin in developing wheat coleoptile by maize Cl and B-peru regulatory genes for anthocyanin synthesis. Breed. Sci. 53, 29–34. 10.1270/jsbbs.53.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz J. O., Xia Y., Blount J., Dixon R. A., Lamb C. (2000). Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 12, 2383–2394. 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen-Forbes C. S., Zhang Y. J., Nair M. G. (2010). Anthocyanin content, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties of blackberry and raspberry fruits. J. Food Compos. Anal. 23, 554–560. 10.1016/j.jfca.2009.08.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buer C. S., Sukumar P., Muday G. K. (2006). Ethylene modulates flavonoid accumulation and gravitropic responses in roots of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140, 1384–1396. 10.1104/pp.105.075671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter R., Doyle S., Luo D., Goodrich J., Romero J. M., Elliot R., et al. (1991). Floral homeotic and pigment mutations produced by transposon-mutagenesis in Antirrhinum majus. Plant Mol. Biol. 212, 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Wang Y., Yang S., Xu Y., Chen X. (2010). Anthocyanin biosynthesis in pears is regulated by a R2R3-MYB transcription factor PyMYB10. Planta 232, 245–255. 10.1007/s00425-010-1170-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff S. A., Cone K. C., Chandler V. L. (1992). Functional analysis of the transcriptional activator encoded by the Maize-B gene - evidence for a direct functional interaction between 2 classes of regulatory proteins. Gene Dev. 6, 864–875. 10.1101/gad.6.5.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Mata G., Mellado-Rojas M. E., Richards-Lewis A., Lopez-Bucio J., Beltran-Pena E., Soriano-Bello E. L. (2010). Plant immunity induced by oligogalacturonides alters root growth in a process involving flavonoid accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Growth Regul. 29, 441–454. 10.1007/s00344-010-9156-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Himi E., Taketa S. (2015). Isolation of candidate genes for the barley Ant1 and wheat Rc genes controlling anthocyanin pigmentation in different vegetative tissues. Mol. Genet. Genomics 290, 1287–1298. 10.1007/s00438-015-0991-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himi E., Maekawa M., Miura H., Noda K. (2011). Development of PCR markers for Tamyb10 related to R-1, red grain color gene in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122, 1561–1576. 10.1007/s00122-011-1555-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho W. W., Smith S. D. (2016). Molecular evolution of anthocyanin pigmentation genes following losses of flower color. BMC Evol. Biol. 16:98. 10.1186/s12862-016-0675-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton T. A., Cornish E. C. (1995). Genetics and biochemistry of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7, 1071–1083. 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayalakshmi N. R., Saraswathi K. T. T., Vijaya B., Raman D. N. S., Suresh R. (2012). Establishment of enhanced anthocyanin production in malva sylvestris l. with different induced stress. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 3, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Joaquin-Cruz E., Duenas M., Garcia-Cruz L., Salinas-Moreno Y., Santos-Buelga C., Garcia-Salinas C. (2015). Anthocyanin and phenolic characterization, chemical composition and antioxidant activity of chagalapoli (Ardisia compressa K.) fruit: a tropical source of natural pigments. Food Res. Int. 70, 151–157. 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.01.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khlestkina E. K. (2013). Genes determining the coloration of different organs in wheat. Russ. J. Genet. Appl. Res. 3, 54–65. 10.1134/S2079059713010085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khlestkina E. K., Antonova E. V., Pershina L. A., Soloviev A. A., Badaeva E. D., Borner A., et al. (2011). Variability of Rc (red coleoptile) alleles in wheat and wheat-alien genetic stock collections. Cereal Res. Commun. 39, 465–474. 10.1556/CRC.39.2011.4.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Baek D., Dong Y. C., Lee E. T., Yoon M. K. (2009). Identification of two novel inactive DFR-A alleles responsible for failure to produce anthocyanin and development of a simple PCR-based molecular marker for bulb color selection in onion (Allium cepa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 118, 1391–1399. 10.1007/s00122-009-0989-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knievel D. C., Abdel-Aal E. S. M., Rabalski I., Nakamura T., Hucl P. (2009). Grain color development and the inheritance of high anthocyanin blue aleurone and purple pericarp in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Cereal Sci. 50, 113–120. 10.1016/j.jcs.2009.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S., Yamamoto N. G., Hirochika H. (2005). Association of VvmybA1 gene expression with anthocyanin production in grape (Vitis vinifera) skin - color mutants. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 74, 196–203. 10.2503/jjshs.74.196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. D., Pickard M. D., Beta T. (2007). Effect of thermal processing on antioxidant properties of purple wheat bran. Food Chem. 104, 1080–1086. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Li S., Chen W., Zhang B., Liu D., Liu B., et al. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of purple pericarps in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 11:e0155428 10.1371/journal.pone.0155428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. P., Liu X. Y., Zhang J., Xia Z. L., Liu X., Qin H. J., et al. (2006). Molecular and functional characterization of sulfiredoxin homologs from higher plants. Cell Res. 16, 287–296. 10.1038/sj.cr.7310036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig S. R., Habera L. F., Dellaporta S. L., Wessler S. R. (1989). Lc, a member of the maize R gene family responsible for tissue-specific anthocyanin production, encodes a protein similar to transcriptional activators and contains the myc-homology region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 7092–7096. 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza G. (2007). Bioactivity, absorption and metabolism of anthocyanins, in Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Human Health Effects of Fruits and Vegetables (Québec: ), 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. (1950). The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 36, 344–355. 10.1073/pnas.36.6.344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L. S., Liu A. (2015). Light signaling induces anthocyanin biosynthesis via AN3 mediated COP1 expression. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e1001223. 10.1080/15592324.2014.1001223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt M. (2001). Wheat evolution: integrating archaeological and biological evidence. Linnean 3, 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Park K. I., Ishikawa N., Morita Y., Choi J. D., Hoshino A., Iida S. (2007). A bHLH regulatory gene in the common morning glory, Ipomoea purpurea, controls anthocyanin biosynthesis in flowers, proanthocyanidin and phytomelanin pigmentation in seeds, and seed trichome formation. Plant J. 49, 641–654. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02988.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazares J., Ghosal D., Wienand U., Peterson P. A., Saedler H. (1987). The regulatory c1 locus of Zea mays encodes a protein with homology to myb proto-oncogene products and with structural similarities to transcriptional activators. EMBO J. 6, 3553–3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroni K., Cominelli E., Consonni G., Gusmaroli G., Gavazzi G., Tonelli C. (2000). The developmental expression of the maize regulatory gene Hopi determines germination dependent anthocyanin accumulation. Genetics 155, 323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porret N., Cousins P., Owens C. (2006). DNA sequence variation within the promoter of VvmybA1 associates with flesh pigmentation of intensely colored grape varieties. Hortscience 41, 1049–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Procissi A., Dolfini S., Ronchi A., Tonelli C. (1997). Light-dependent spatial and temporal expression of pigment regulatory genes in developing maize seeds. Plant Cell 9, 1547–1557. 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri A., Macdonald G. E., Altpeter F., Haller W. T. (2007). Mutations in phytoene desaturase gene in fluridone-resistant Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) biotypes in Florida. Weed Sci. 55, 412–420. 10.1614/WS-07-011.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z., Wang X., Gao J., Guo Y., Huang Z., Du Y. (2016). The tomato Hoffman's anthocyaninless gene encodes a bHLH transcription factor involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis that is developmentally regulated and induced by low temperatures. PLoS ONE 11:e0151067. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocchio F., Wing J. F., van der Woude K., Mol J. N. M., Koes R. (1998). Analysis of bHLH and MYB domain proteins: species-specific regulatory differences are caused by divergent evolution of target anthocyanin genes. Plant J. 13, 475–488. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revanappa S. B., Salimath P. V. (2011). Phenolic acid profiles and antioxidant activities of different wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties. J. Food Biochem. 35, 759–775. 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2010.00415.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh K., Onishi K. I., Thidar K., Sano Y. (2004). Allelic diversification at the C (OsC1) locus of wild and cultivated rice: nucleotide changes associated with phenotypes. Genetics 168, 997–1007. 10.1534/genetics.103.018390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamini F., Ozkan H., Brandolini A., Schäferpregl R., Martin W. (2002). Genetics and geography of wild cereal domestication in the near east. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 429–441. 10.1038/nrg817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield S. R., Huang L., Brandt A. S., Gill B. S. (2005). Development of a virus-induced gene-silencing system for hexaploid wheat and its use in functional analysis of the Lr21-mediated leaf rust resistance pathway. Plant Physiol. 138, 2165–2173. 10.1104/pp.105.061861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoeva O. Y., Gordeeva E. I., Khlestkina E. K. (2014). The regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in the wheat pericarp. Molecules 19, 20266–20279. 10.3390/molecules191220266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Selvi M. T., Sharma R. (1999). Sunlight-induced anthocyanin pigmentation in maize vegetative tissues. J. Exp. Bot. 50, 1619–1625. 10.1093/jxb/50.339.1619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solano R., Nieto C., Avila J., Canas L., Diaz I., Paz-Ares J. (1995). Dual DNA binding specificity of a petal epidermis-specific MYB transcription factor (MYB.Ph3) from Petunia hybrida. EMBO J. 14, 1773–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltész A., Vágújfalvi A. (2013). Transgenic barley lines prove the involvement of TaCBF14 and TaCBF15 in the cold acclimation process and in frost tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1849–1862. 10.1093/jxb/ert050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styles E. D., Ceska O., Seah K. T. (1973). Developmental differences in action of R and B alleles in maize. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 15, 59–72. 10.1139/g73-007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney M. T., Thomson M. J., Pfeil B. E., McCouch S. (2006). Caught red-handed: Rc encodes a basic helix-loop-helix protein conditioning red pericarp in rice. Plant Cell 18, 283–294. 10.1105/tpc.105.038430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takos A. M., Walker A. R. (2006). Light-induced expression of a MYB gene regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples. Plant Physiol. 142, 1216–1232. 10.1104/pp.106.088104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee T. S., Qualset C. O. (1975). Bulk populations in wheat breeding: comparison of single-seed descent and random bulk methods. Euphytica 24, 393–405. 10.1007/BF00028206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tereshchenko O. Y., Arbuzova V. S., Khlestkina E. K. (2013). Allelic state of the genes conferring purple pigmentation in different wheat organs predetermines transcriptional activity of the anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes. J. Cereal Sci. 57, 10–13. 10.1016/j.jcs.2012.09.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- This P., Lacombe T., Cadle-Davidson M., Owens C. L. (2007). Wine grape (Vitis vinifera L.) color associates with allelic variation in the domestication gene VvmybA1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 723–730. 10.1007/s00122-006-0472-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli C., Consonni G., Dolfini S. F., Dellaporta S. L., Viotti A., Gavazzi G. (1991). Genetic and molecular analysis of Sn, a light-inducible, tissue specific regulatory gene in maize. Mol. Gen. Genet. 225, 401–410. 10.1007/BF00261680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutter D. (2006). Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 4, 147–157. 10.1007/s10311-006-0068-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. F., Wei X., Fan R., Zhou H., Wang X., Yu C., et al. (2011). Molecular analysis of common wheat genes encoding three types of cytosolic heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90): functional involvement of cytosolic Hsp90s in the control of wheat seedling growth and disease resistance. New Phytol. 191, 418–431. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yang J., Min Z., Fan W., Firon N., Pattanaik S., et al. (2016). Altered phenylpropanoid metabolism in the maizelc-expressed sweet potato (ipomoea batatas) affects storage root development. Sci. Rep. 6:18645. 10.1038/srep18645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. S., Stoner G. D. (2008). Anthocyanins and their role in cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 269, 281–290. 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Q., Hou X. J., Zhang B., Chen W. J., Liu D. C., Liu B. L., et al. (2016). Identification of a candidate gene for Rc-D1, a locus controlling red coleoptile colour in wheat. Cereal Res. Commun. 44, 35–46. 10.1556/0806.43.2015.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z. H., Wan Y. F., Liu K. F., Zheng Y. L., Wang D. W. (2002). Identification of a novel HMW glutenin subunit and comparison of its amino acid sequence with those of homologous subunits. Chinese Sci. Bull. 47, 220–225. 10.1360/02tb9053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeven A. C. (1991). Wheats with purple and blue grains: a review. Euphytica 56, 243–258. 10.1007/BF00042371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. N., Li W. C., Wang H. C., Shi S. Y., Shu B., Liu L. Q., et al. (2016). Transcriptome profiling of light-regulated anthocyanin biosynthesis in the pericarp of Litchi. Front. Plant Sci. 7:963. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Butelli E., Martin C. (2014). Engineering anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 19, 81–90. 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. B., Li S. F., Deng Z. Y., Wang X. P., Chen T., Zhang J. S., et al. (2011). Molecular analysis of three new receptor-like kinase genes from hexaploid wheat and evidence for their participation in the wheat hypersensitive response to stripe rust fungus infection. Plant J. 52, 420–434. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.