Abstract

Study Objective

Produce Girl Talk, a free smartphone application containing comprehensive sexual health information, and determine the application’s desirability and appeal among teenage girls.

Design, Setting and Participants

39 girls ages 12–17 from Rhode Island participated in a two-phase prospective study. In Phase I, 22 girls assessed a sexual health questionnaire in focus groups. In Phase 2, 17 girls with iPhones® used Girl Talk for two weeks and answered the revised sexual health questionnaire and interview questions before and after use.

Main Outcome Measures

Participants’ responses to the sexual health questionnaire, interviews and time viewing the application were used to determine feasibility and desirability of Girl Talk.

Results

Girl Talk was used on average for 48 minutes during participants’ free time on weekends for 10–15 minute intervals. Reported usefulness of Girl Talk as a sexual health application increased significantly from baseline to follow-up (35.3% vs. 94.1%; p < .001). Knowledge improved most in topics related to Anatomy and Physiology (4.2%), Sexuality and Relationships (3.5%) and STI Prevention (3.4%). Most participants (76.5%) were exposed to sexual health education prior to using Girl Talk, but 94.1% of participants stated that the application provided new and/or more detailed information than health classes.

Conclusion

Girl Talk can potentially connect teenage girls to more information about sexual health versus traditional methods, and participants recommended the application as a valuable resource to learn about comprehensive sexual health.

Keywords: Adolescent, Health Education, Prospective Studies, Reproductive Health, Sexual Behavior, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Surveys and Questionnaires, Healthcare Smartphone Applications

Background

The World Health Organization declared in 2010 that research should focus on the development of interventions related to comprehensive sexual health education for teenagers to combat unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1 Legislation in the United States does not mandate comprehensive sexual health education for teens despite previous research attesting to the success of such education in the classroom.2 National organizations have also recommended that doctors provide anticipatory sexual health education and guidance to teenagers. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that young women have an anticipatory sexual health information visit with a gynecologist between ages 13–15, but the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that physicians respond to sexual health questions when patients are between ages 15–17.3,4 Current efforts at early intervention do not reach teenagers who have already reached sexual debut by ages 14 and 15.5 New and innovative ways to deliver sexual health information are therefore needed to better support teenagers.

Smartphone usage has increased to 73% among American adolescents since 2013 alongside the widespread success of the Apple App Store®.6,7,8 Smartphone applications have been shown to be highly effective in providing health information to teenagers. Krishna, Boren, and Balas demonstrated in a 2009 systematic review that mobile phone usage incorporating abbreviated reminder services and general adolescent health education materials can improve health outcomes among teenagers.9 Many health-based smartphone applications already provide information to users, but few smartphone applications incorporate evidence-based theories for behavior change.10 Furthermore, there are few smartphone applications related to sexual and reproductive health that are available to users.10 Using a smartphone application to provide sexual health information to younger populations may aid in increasing awareness of sexual risk behaviors before sexual debut.11,12 Over 46% of surveyed websites in 2010 that provided sexual health information contained errors or inaccurate content. Providing accurate, comprehensive and up-to-date sexual health education materials to teenagers through smartphones versus websites may improve their sexual health outcomes.6,12

Teens in the United States, especially in Rhode Island, seek out information related to sexual health through electronic resources over other information outlets.13 In a prior survey, Rhode Island middle and high school students stated that they most often utilize social media and peers to obtain sexual health education, respectively.13 Neither age group stated that they sought out medical advice from medical practitioners.13 Parents and guardians were the least likely to be utilized as resources by male and female teenagers.13 Rhode Island’s state legislature required both public and private schools to implement “medically accurate, age-appropriate and culturally appropriate and unbiased” sexual health education for students upon approval through the state’s Department of Health.14,15 As of 2015, Rhode Island’s sexual health curriculum does not encourage teenagers discuss sexual health with parents or providers, and legislation does not contain information on how sexual health content in schools is regulated or evaluated.14 New methods are needed to encourage discussions on sexual health between teenagers and trusted adults. Smartphone usage has the potential to provide accurate and comprehensive sexual health information to teens that is supported by providers, parents and other trusted adults.16

Based on the growing use of social media and smartphones by teenagers to learn about sexual health, the evidence-based objectives of our research study were two-fold. Our first objective was to design Girl Talk, an Apple-compatible smartphone application providing comprehensive sexual health education materials to girls ages twelve to seventeen. We proposed that introducing age-appropriate, comprehensive and culturally representative sexual health materials through a free and readily accessible media format like Girl Talk would allow teenage girls to access information needed to improve knowledge of risky sexual behaviors. Our second objective was to test the feasibility and desirability of Girl Talk among female adolescents. We proposed that Girl Talk could provide appealing and comprehensive sexual health information to a wide audience of teenage girls.

Materials and Methods

Application Design

Girl Talk’s interface incorporated four guiding principles: inclusion of trusted sexual health information, visually appealing graphics, compatibility with iPhones® and age-appropriate, straightforward content. First, the application’s content included pre-existing and accurate sexual health information from government agencies (i.e. the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention17 and the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Adolescent Health18, and Rhode Island Departments of Education19 and Health20), national organizations (i.e. Planned Parenthood21, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy22 and the Representation Project23), community-based organizations (i.e. Brown University’s Office of Health Promotion24) and publications highlighting diverse identities in education such as Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice by Maurianne Adams.25

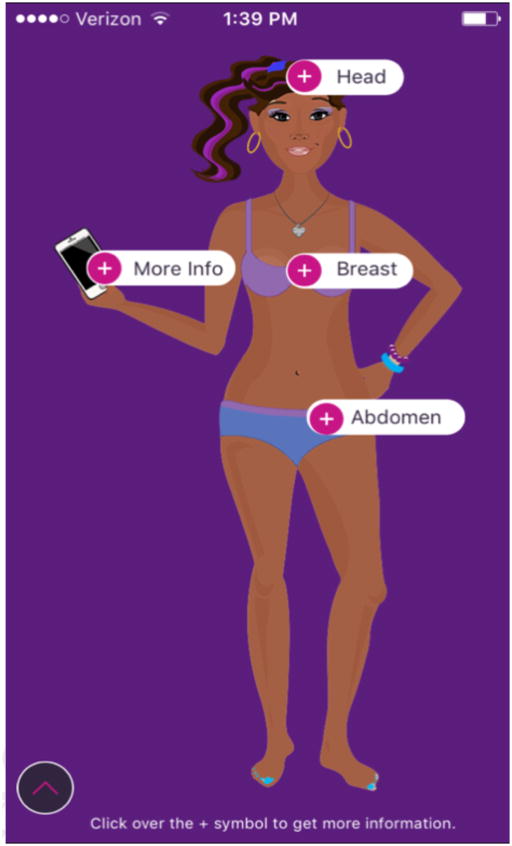

Second, the graphics, icons, and content within the Girl Talk application were visually appealing. Bold color schemes, based on the coding produced by software developers from Boston Technology Corporation, captured the attention of users. Figure 1 features images of Girl Talk’s interface.

Figure 1.

Girl Talk Navigation Menu

Third, Girl Talk was an Apple®-compatible smartphone application available to many teenage girls. Boston Technology Corporation designed the application to be viewed on iPhone® versions 4 and later.

Lastly, all content within Girl Talk was formatted to be easy to navigate and readily understood based on the age and grade level of users. Groupings of topics within Girl Talk included:

a “Head” section, which included information about mental health, body image, gender and sexuality, and relationships

a “Breast” section, which included information about breast health and self-examination

an “Abdomen” section, which included information about healthy lifestyles and reproductive health, including the menstrual cycle and contraception; and

a “More Info” section, which clarified common misconceptions about sexual health and provided additional resources such as websites and hotlines

Medical and undergraduate students wrote and updated content for Girl Talk on a collaborative writing platform (i.e. a “Wiki” online database). All students possessed knowledge in relevant areas including adolescent sexual health education, obstetrics, adult gynecology, and pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Students also consistently revised the Wiki in order to maintain the application’s accuracy.

Study Design

Phase I of the study was conducted at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island in Providence, Rhode Island after IRB review and included twenty-two enrolled participants. To meet eligibility criteria, participants were required to be female Rhode Island residents between the ages of twelve and seventeen. Recruitment sites for participants included local clinics, youth community centers, private pediatric practices, obstetrician-gynecologist offices, advertisements on local bus routes, school-based nurses and health educators, and a Spanish-language radio talk show. All youth participants signed an assent form in the presence of two investigators and a parent/guardian who also signed a consent form. Participants were separated into two age-specific, moderator-led focus groups during Phase I to validate a sexual health questionnaire for clarity, comprehension and age-appropriate language. Feedback from Phase I focus groups shaped revisions to the questionnaire before use in Phase II. The questionnaire was divided into five distinct categories: anatomy and physiology, mental and physical health, pregnancy prevention, sexuality and relationships and prevention of sexually transmitted infections. The Rhode Island Department of Education Comprehensive Health Instructional Outcomes released in 2015 also guided the separation of questions into the listed sections for analysis. Participants in Phase I were compensated with $20 in iTunes gift cards.

Phase II of the study was also conducted at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island and included twenty enrolled participants. Phase II participants were required to meet Phase I’s eligibility criteria and also owned an Apple iPhone® versions 4S, 5, 5S, 6 or 6 Plus. The same recruitment strategies used for Phase I were utilized for Phase II. Participation included attending two appointments with the study team as well as use of the Girl Talk application. During the first appointment, participants answered qualitative interview questions regarding smartphone usage and the sexual health questionnaire developed in Phase I to test sexual health knowledge. All interview questions were standardized by investigators through the use of an interview script. Participants then downloaded Girl Talk, created a user account within the application and completed the questionnaire within the application. After completing the questionnaire, participants were able to select the ethnicity of their Girl Talk character and were given a tutorial of the application’s functions. All participants used the application for a two-week period and were sent notifications on their iPhones® every 72 hours to encourage self-elected use of the application. At the close of two weeks, participants were scheduled for a second appointment during which they evaluated all content featured in Girl Talk as well as the application’s overall appeal. Participants also provided suggestions to improve the application’s content and format. Prior to deleting the application at the conclusion of the study, participants were asked to retake the sexual health questionnaire to determine any improvements in sexual health knowledge. Three participants were lost to follow-up during Phase II resulting in the analysis of 17 respondents at baseline and follow-up. Participants in Phase II were compensated with $30 iTunes® gift cards.

Statistical Evaluation

Phase I focus groups provided feedback for the sexual health questionnaire, but the responses were not statistically analyzed. Only responses provided by participants during Phase II were analyzed. Phase II participants’ responses to the 45 questions in the sexual health questionnaire were compiled into an online database maintained by Boston Technology Corporation on a GoDaddy™ secure server. All responses were downloaded and assigned quantitative values (i.e. 1 = correct, 0 = incorrect) in Microsoft Excel 2013. Survey questions were then divided into the five categories determined in Phase I: anatomy/physiology (7 items), mental/physical health (6 items), pregnancy prevention (15 items), sexuality and relationships (10 items) and STI prevention (7 items). R Studio, an open-source statistical software package, was used to conduct statistical analyses and create graphical representations of all collected data.26

Descriptive statistics were computed from participants’ interview responses and in-application survey responses. Participants’ mean hourly use of their iPhones® and the application was based on self-reported data. Correct responses to the sexual health questionnaire items were summed to form a total knowledge score as well as individual domain scores for each of the five domains of the scale. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level readability scores in Microsoft Word 2013 were used as a literary assessment tool to evaluate age appropriateness of Girl Talk by measuring the grade level and length (i.e. word count) of questions and content presented to participants.27 Flesch-Kincaid scores and changes in participants’ response accuracy were then compared to evaluate each section of Girl Talk.

Results

Participant Information

The average age of Phase I participants was 14.6 years. Among 10 participants in the focus groups of 12–14 year olds, the average age was 13.4 years. Of 12 participants in the focus groups of 15–17 year olds, the average age was 15.7 years.

The average age of Phase II participants was 15.8 years. Almost all (94.1%) of participants from Phase II stated that they had received at least some form of sexual health information within the 12 months prior to study enrollment. The majority (76.5%) of participants who had received sexual health information reported receiving the information from either an educator at their school or a health class provided by their school.

Girl Talk and iPhone® Usage

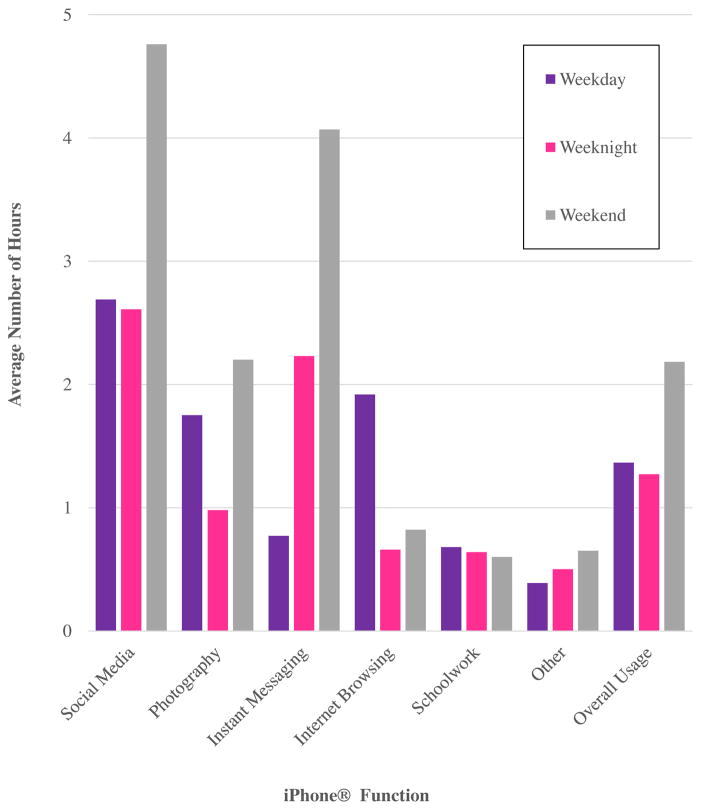

Participants reported average iPhone® usage of 5.7 hours during weekdays, 7.6 hours on weeknights and 13.1 hours on weekends. Participants reported using social media and instant messaging capabilities on their iPhones® more than any other function. On average, social media applications were used for 2.6–4.8 hours each week, and instant messaging was utilized for 0.7–4.1 hours during the week. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of participants’ hourly use of iPhone® functions by time of day. Note that features listed under “other” were reported by participants and include playing music, games or reading electronic books. During the follow-up session, participants reported using Girl Talk for 48 minutes on average over the two-week period. Most participants (82.4%) stated that they used the application in increments of ten to fifteen minutes, and 88.2% of participants noted increased usage (i.e. twenty minutes) of Girl Talk during weekends.

Figure 2.

Participants’ Weekly iPhone® Usage by iPhone® Function

Categorical Changes in Knowledge Based on Grade Level and Word Count

Improvements in knowledge among Phase II participants were noted for anatomy and physiology (4.2%), sexuality and relationships (3.5%) and STI prevention (3.4%) which all exceed the 2.0% overall change in knowledge. No changes in knowledge were noted for mental and physical health or pregnancy prevention. Based on Flesch-Kincaid scores, the average grade level of survey questions was 6.5 versus 8.4 for content. Questions for each category consisted of 14.5 words on average, with a range 12.8 to 16.7. The average number of words for content directly related to one or more survey questions was 52; however, content related to questions on mental and physical health was an outlier with an average of 127 words per content area while the other question categories averaged between 32 and 45 words per content area. “Mental and physical health” and “Pregnancy Prevention” were the only categories that did not show improvement in knowledge. Table 1 provides a summary of word counts, grade level and changes in knowledge for all sections in Girl Talk.

Table 1.

Participants’ change in accuracy about sexual health topics from baseline to follow-up based on application category relative to grade level and word count

| Category | Average change in accuracy among participan ts (%) | Average Grade Level of Questions | Average Word Count of Questions | Average Grade Level of Related Content | Average Word Count of Related Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomy and Physiology | 4.2 | 7.2 | 16.7 | 7.3 | 43.0 |

| Sexuality and Relationships | 3.5 | 6.3 | 12.8 | 9.2 | 45.5 |

| STI Prevention | 3.4 | 6.3 | 13.7 | 8.8 | 32.3 |

| Mental and Physical Health | 0.0 | 6.1 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 127.0 |

| Pregnancy Prevention | 0.0 | 6.7 | 14.7 | 8.4 | 41.3 |

| All Categories | 2.0 | 6.5 | 14.5 | 8.4 | 52.5 |

Seeking Advice

When asked to select their top 3 sources of information on sexual intercourse, contraception and pregnancy, participants were most likely to select doctors (82.4%) followed by nurses (76.5%) and Planned Parenthood (52.9%) at baseline. At follow-up, participants had an increased preference in consulting doctors (88.2%) and a slight decrease in preference for nurses (64.7%). No changes at follow-up were noted for participants’ preference to consult Planned Parenthood.

When asked to select their top 3 sources of information on love and sexual relationships at baseline, participants were most likely to select parents or guardians (58.8%) followed by doctors (52.9%) or friends (41.1%). At follow-up, participants’ preference for doctors (70.6%) and parents/guardians increased (64.7%). In addition, preference for nurses increased significantly between baseline and follow-up (17.6% versus 41.1%; p < .05).

When participants were asked if they shared information from Girl Talk with their family during Phase II, participants were more likely to report that they shared information on mental health with family members than other content areas. When participants were asked what topics in Girl Talk they discussed with friends, participants were more likely to report sharing information on contraception than other content areas.

Participants’ Impressions of Girl Talk

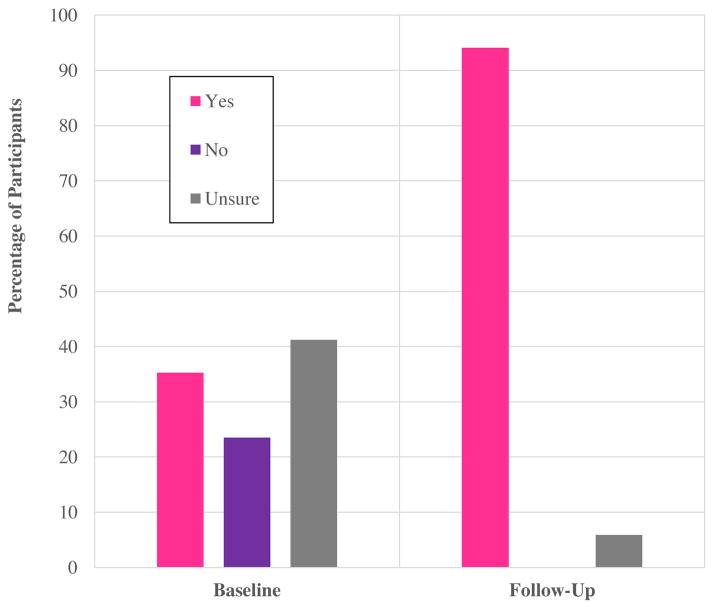

Nearly all participants in Phase II (94.1%) stated that most or all of their friends owned smartphones that could support Girl Talk. When asked if they or other teenage girls would use Girl Talk to learn about sexual health, there was a statistically significant increase from baseline to follow-up (35.3% vs 94.1%; Fisher’s Exact p = 0.0008). Changes in participants’ responses are outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Reported usefulness of Girl Talk by participants at baseline and follow-up

Content strongly favored by participants included topics such as healthy lifestyles (76.5%), body image (58.8%) and pregnancy prevention (52.9%). While 76.5% of participants had previous exposure to sexual health education prior to study enrollment, 94.1% of participants stated during interviews that Girl Talk provided new and/or more detailed information compared to health classes, especially in relation to breast health, contraception and STI prevention.

Suggested Additions to Girl Talk

When asked if any additional features should be included in Girl Talk, participants were interested in adding features to the application that offered resources through additional interactive formats. Features such as calendars or tracking systems for menstrual cycles were suggested by participants in order to further apply knowledge received related to anatomy and physiology. Inclusion of live chat rooms, forums or messaging within Girl Talk was also proposed in order to quickly answer remaining questions about sexual health. Providing region-specific information such as maps with locations of offices providing gynecological services was also strongly encouraged by participants after using the application.

Discussion

Our study results show that Girl Talk is a feasible sexual health educational tool that is appealing to teenage girls. Increased usage of the application in small increments during participants’ free time mirrors their self-reported use of other features on their iPhones®. This finding suggests that Girl Talk can be integrated into the daily use of smartphones amongst teenagers for quick access to reliable sexual health information. Since our study sample was recruited from a wide variety of locations, our findings mirror the prevalent use of smartphone applications among adolescents as noted in past research.28 Participants’ enthusiasm and interest in recommending the application to their friends also mirrors trends in previous research and highlights the opportunity to expand the use of Girl Talk to a larger adolescent population.16 We demonstrated Girl Talk’s ability to convey more sexual health information than traditional sexual health education in a private, timely and accurate manner. Providing content directly related to community-based resources also gave participants new information that was related to their daily experiences. The application also has the potential to bridge the gap between teenagers, medical providers and parents by encouraging girls to initiate conversations about contraception use, body image, healthy lifestyles and holistic well-being with trusted adults.

The limitations to the study were the short-term exposure to Girl Talk, English-only content within the smartphone application, iPhone-only access, and the exclusion of interactive features due to medical-legal confidentiality challenges with integrating features such as real-time question and answer texting services. Inclusion of application features desired by our participants such as resource maps, period trackers and live messaging/chat forums would have provided additional health communication opportunities for participants. Long-term versus short-term exposure to Girl Talk is needed to further evaluate potential improvements in knowledge. Small improvements in knowledge during Phase II may be attributed to the presentation of content at higher grade levels than the questions posed to participants in the sexual health questionnaire. Variance in the length of content of each section of Girl Talk might also impact short-term knowledge improvements among participants. Such limitations can be easily overcome in the future by revising sections in Girl Talk with outliers in content length and readability score before expanding long-term usage of the application to a larger population through a multi-site trial. Continuing to expand our collaborations with community-based organizations throughout the country can also provide the support necessary to include more features in the application that were noted by participants.

Our future directions are to focus on (1) revising sections of the application, (2) expanding availability to Android platforms and in multiple language formats, (3) extending the amount of time that participants spend on the application, and (4) including features recommended by participants. Making the grade level and length of each Girl Talk section more consistent will provide an opportunity for girls to continue receiving age-appropriate and straightforward information about sexual health. Expanding the availability of Girl Talk’s content to both iPhone® and Android® platforms will allow for more girls to access clear sexual health education materials on their phones. Providing this information in multiple languages will also aid in promoting widespread use of the application across a diverse group of adolescents. Providing longer-term access to Girl Talk may provide the information needed to determine long-term changes in sexual health knowledge. Expanding use of the application to a larger group of teenage girls throughout the country will allow for study findings to be generalized to larger populations of girls in the United States. Adding additional interactive features that were recommended by participants may also encourage girls to continue engaging in learning about sexual health after using Girl Talk.

Summary

Developing a smartphone application for comprehensive sexual health education is feasible and practical. The application is well-liked, accessible and can provide opportunities for clear, factual transmission of information to teenage girls.

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgments

The work described in this manuscript was funded through the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) – Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Research Fellowship in Contraceptive Benefit/Risk Communication.

Additonal Acknowledgments

In addition to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, we thank the Reproductive Scientist Development Program, Boston Technology Corporation, Youth in Action RI, the Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) program sponsored by Rhode Island chapter of the National Coalition of 100 Black Women (NCBW-RI) and 1290 AM Latino Public Radio. We also thank Aida Manduley, Andrea Rollins, MD, Amy Corrado, RN, Roxannne Vrees, MD, Noah Bickford, Kim Cotter, Jeff Fernandez, Kimber-lee Palermo, Ashley Parker, Keomarney Phan, Crystal Ware, Gary Wessel, PhD, Christina Raker, PhD, Amber Lau, Susan Elmore, Jacqueline Dryer, Andrea Pacheco-Medeiros, Ruben Alvero, MD and Maureen G. Phipps, MD, MPH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interests were involved in the work described in this manuscript.

-

Category 1: The following authors contributed to the study’s conception and design, data acquisition and data analysis/interpretation.Lynae M. Brayboy, MD, Lucy Schultz, MA, Benedict S. Landgren Mills, MD, Noelle Spencer, BA, Alexandra Sepolen, BA Candidate, Taylor Mezoian, BS, Carol Wheeler, MD and Melissa A. Clark, PhD

-

Category 2: The following authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript.Lynae M. Brayboy, MD, Lucy Schultz, MA, Benedict S. Landgren Mills, MD, Noelle Spencer, BA, Alexandra Sepolen, BA Candidate, Taylor Mezoian, BS, Carol Wheeler, MD and Melissa A. Clark, PhD

-

Category 3: The following authors contributed to the final approval of the manuscript upon submission.Lynae M. Brayboy, MD, Lucy Schultz, MA, Benedict S. Landgren Mills, MD, Noelle Spencer, BA, Alexandra Sepolen, BA Candidate, Taylor Mezoian, BS, Carol Wheeler, MD and Melissa A. Clark, PhD

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Developing Sexual Health Programmes: A Framework for Action (PDF) World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alford S. Sex Education Programs: Definitions & Point-by-Point Comparison. Transitions: The Controversy over Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Programs. 2001;12:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanfilippo JS, Davis A, Hertweck SP. Obstetrician gynecologists can and should provide adolescent health care. ACOG Clin Rev. 2003;8(7):1,15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adolescence 11–21 Years (PDF) Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents. 2015:231–298. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2013. Surveillance Summaries. 2014;63(4):1–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alptraum L. Are Smartphone Apps the Sexual Health Tech of the Future? (webpage) Boinkology. 2013;101 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins RL, Martino SC, Shaw R. Influence of New Media on Adolescent Sexual Health: Evidence and Opportunities (PDF) RAND Health. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apple. App Store® Rings in 2015 with New Records (webpage) Apple; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA. Healthcare via Cell Phones: A Systematic Review. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009;15(3):231–240. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West JH, Hall PC, Hanson CL, et al. There’s an App for That: Content Analysis of Paid Health and Fitness Apps. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frost JJ, Forrest JD. Understanding the Impact of Effective Teenage Pregnancy Prevention Programs. Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;27:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buhi ER, Daley EM, Oberne A, et al. Quality and accuracy of sexual health information web sites visited by young people. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:206–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosengard C, Tannis C, Dove DC, et al. Family Sources of Sexual Health Information, Primary Messages, and Sexual Behavior of At-Risk, Urban Adolescents. Am J Health Ed. 2013;43(2):83–92. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2012.10599223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.State Policies in Brief: Sex and HIV Education (PDF) Guttmacher Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rules and Regulations for School Health Programs (PDF) Rhode Island Department of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawni A, Cederna-Meko C, LaChance J. Feasibility & Perception of Cell Phone Based, Health Related Communication with Teens in an Economically Depressed Area. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(2):S28–S29. doi: 10.1177/0009922816645516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sexual Risk Behaviors: HIV, STD, & Teen Pregnancy Prevention (Web) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adolescent Health Topics (Web) Department of Health and Human Services Office of Adolescent Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gist DA. Comprehensive Health Instructional Outcomes (PDF) Rhode Island Department of Education; 2015. pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adolescent Health Publications (Web) Rhode Island Department of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Planned Parenthood. 2015. Sexual Health Topics (Web) [Google Scholar]

- 22.The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. 2012. What Works: Curriculum-Based Programs That Help Prevent Teen Pregnancy (PDF) [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Representation Project. 2015. Miss Representation Screening Guide (PDF) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown University BWell Health Promotion. 2015. Sexual Health (Web) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams M, Bell LA, Goodman DJ, et al. Sexism, Heterosexism and Trans* Oppression: An Integrated Perspective. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice. 2016;3:183–212. [Google Scholar]

- 26.RStudio. 2016. Why RStudio? (Web) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callan J, Si L. A Statistical Model for Scientific Readability (PDF) Assoc Comp Mach. 2000:574–576. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenhart A. Teens, Social Media and Technology Overview 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. A Majority of Teens Report Access to a Computer, Game Console, Smartphone and Tablet. [Google Scholar]