Abstract

Trichloroethene (TCE) degradation by Fe(III)-activated calcium peroxide (CP) in the presence of citric acid (CA) in aqueous solution was investigated. The results demonstrated that the presence of CA enhanced TCE degradation significantly by increasing the concentration of soluble Fe(III) and promoting H2O2 generation. The generation of HO• and O2−• in both the CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems was confirmed with chemical probes. The results of radical scavenging tests showed that TCE degradation was due predominantly o direct oxidation by HO•, while O2−• strengthened the generation of HO• by promoting Fe(III) transformation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. Acidic pH conditions were favorable for TCE degradation, and the TCE degradation rate decreased with increasing pH. The presence of Cl−, HCO3−, and humic acid (HA) inhibited TCE degradation to different extents for the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. Analysis of Cl− production suggested that TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system occurred through a dechlorination process. In summary, this study provided detailed information for the application of CA-enhanced Fe(III)-activated calcium peroxide for treating TCE contaminated groundwater.

Keywords: Calcium peroxide, Trichloroethene (TCE), Citric acid, Ferric ion, Free radicals, oxidation

1. Introduction

Groundwater and soil contamination by chlorinated solvents throughout the world has imposed significant threats to the ecological environment and endangered human health. Trichloroethene (TCE), which was used extensively in metal degreasing, dry cleaning and used as extraction solvent and components for synthesis, is a ubiquitous contaminant at hazardous waste sites in America [1]. Due to its harmful characteristics such as carcinogenicity and reproductive toxicity, TCE has been identified as one of the priority existing chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act by US Environmental Protection Agency [2]. As a result, the development of remediation technologies for chlorinated-solvent contaminated sites has been a primary focus of research and development efforts for many years.

In situ chemical oxidation (ISCO) accomplished by injecting chemical oxidants directly into contaminated groundwater or soil to destroy contaminants is an increasingly popular technology possessing wide potential for contaminated site remediation. Among various in situ oxidants, Fenton’s reagent has attracted much attention due to its high potential to oxidize a wide range of contaminants and its minor impact on the environment. The Fenton or Fenton-like reactions use Fe(II) and Fe(III) to catalyze the reaction with H2O2, which produces various free radicals via the propagation reactions (Eqs. 1–5), including hydroxyl radical (HO•), perhydroxyl radicals (HO2•), superoxide radical anions (O2−•) and hydroperoxide anions (HO2−), etc. [3]. HO• generated by Eq. 1 possesses strong oxidizing properties, and can oxidatively decomposed a wide range of organic contaminants [4].

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Compared to the Fenton reaction, the rapid consumption of H2O2 can be avoided in Fenton-like reactions due to slow Fe(II) formation. However, the contaminant degradation rates for Fenton-like reactions are typically much slower and Fe(III) has the potential to precipitate under neutral pH conditions. To alleviate the precipitation of Fe(III) and enhance the degradation efficiency of contaminants, chelating agents, such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), oxalic acid (OA), nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), and citric acid (CA), have been employed in Fenton-like reactions [5–7].

EDTA is an efficient and commonly used chelating agent. However, its recalcitrant nature makes it difficult to be biodegraded, and its persistence in groundwater may result in an elevated risk due to metal leaching. OA and CA are organic multidentate compounds commonly present in nature. Citrate was found to be rapidly biodegraded in calcareous and non-calcareous soils while oxalate was resistant to microbial degradation [8]. It was also reported that the complexes of OA with ferric ion have weaker stability than that of CA [9]. In contrast to EDTA, NTA is easily biodegraded to CO2, H2O, and inorganic nitrogen [7]. However, NTA and its salts have acute toxicity and possible carcinogenicity to humans, which lead to negative effects [10]. As an important intermediate of the Krebs cycle in the metabolism of all aerobic organisms, CA can be easily biodegraded to CO2 and H2O without formation of toxic products. CA participates in the biodegradation of contaminants as nutrients for microorganisms thus making it harmless to the environment. Wen et al. investigated the biodegradation of rhamnolipid, EDTA and CA, and the most rapid degradation of CA was found in metal contaminated soils [11]. Compared with EDTA, OA and NTA, CA is more compatible with bioremediation and environmentally friendly. In addition, Liang et al. investigated the application of various chelating agents including EDTA, STPP, HEDPA, and CA in TCE degradation by an activated persulfate system to manipulate the quantity of ferrous ion in solution [12]. The results indicated that CA was the most effective activator for the destruction of TCE, and a CA/Fe(II) molar ratio of 1/5 was suitable to maintain sufficient quantities of soluble iron in solution. Lewis et al. reported that citrate modified Fenton reaction dechlorinated TCE effectively in aqueous solution and organic phases at near neutral pH and the decomposition rate of H2O2 was regulated with the dose of chelating agent [13].

In recent years, attempts have been made to search for stable alternatives for H2O2 to avoid the drawback of H2O2 instability. Calcium peroxide (CaO2, CP) is considered as a versatile and effective solid source of H2O2 that can liberate H2O2 via Eq. 6 [14, 15].

| (6) |

The generation of H2O2 from CP can be regulated by adjusting the solution pH and the inefficient parallel reactions can be reduced. The characteristics of CP make it convenient for transport and storage, and to improve the persistence of oxidants in groundwater. However, it should be noted that excessive addition of calcium could increase the hardness of water and affect its quality for public and industrial use.

Calcium peroxide has been used in a few prior cases for soil and groundwater remediation. The application of CP in the remediation of PCB-contaminated soil showed significant contaminant removal and minimal impact on soil microbial activity [16]. Zhang et al. studied the effective treatment of waste activated sludge containing EDCs (Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals) by CP [17], and CP has also been used as an oxidant to stimulate the degradation of TCE in modified Fenton chemistry in our previous study [18].

However, to the best of our knowledge, the ability of CA to enhance the Fe(III)-catalyzed oxidative capacity of CP has not been investigated. In this study, TCE was selected as the target contaminant to investigate its degradation by CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems. The specific purposes are (1) to assess the enhanced effect of CA on TCE degradation; (2) to elucidate free radicals generated and the TCE degradation mechanisms for the CP/Fe(III)/CA system; and (3) to evaluate the influence of solution matrix on TCE degradation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Calcium peroxide (75% CP), trichloroethene (TCE, 99.0%), and humic acid (HA, fulvic acid > 90%) were purchased from Aaladdin Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Carbon tetrachloride (CT, 99.5%), n-hexane (C6H14, 97%), and anhydrous ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3, 99.0%) were acquired from Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Citric acid (CA, 99.0%), sodium chloride (NaCl, 99.5%), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, 99.5%), sodium phosphate dibasic dodecahydrate (Na2HPO4·12H2O, 99.0%), sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate (NaH2PO4·2H2O, 99.0%), 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (C12H8N2•H2O, 98%), hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl, 99.0%), isopropanol (IPA, 99.5%), trichloromethane (CF, 99.0%), and nitrobenzene (NB, 99.0%) were purchased from Shanghai Jingchun Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals were used without further purification and all solutions in the experiments were prepared with ultrapure water from a Milli-Q water process (Classic DI, ELGA, Marlow, UK.). Groundwater used in selected experiments was obtained from a site in Minhang, Shanghai, China. It was collected from a well screened approximately 10 m below the ground surface. Water quality characteristics are provided in Table S3 (Supporting information).

2.2. Experimental procedures

Stock solutions of TCE, NB, and CT were prepared by dissolving pure TCE, NB or CT liquid in ultrapure water with gentle agitating. Various stock solutions were diluted to the desired concentrations and added to the reactor for different tests. The reactor used for all reactions was a customized cylindrical glass container (250 mL) with two ground glass mouths for dosing and sampling, respectively, in which a magnetic stirrer was used to maintain well-mixed conditions. The reaction temperature was held at 20 ± 0.5°C by a thermostat circulating water bath (Scientz SDC-6, Ningbo, China) and the solution pH was measured and recorded with a pH meter (Mettler-Toledo DELTA 320, Greifensee, Switzerland). After all of the chemicals (e.g. Fe2(SO4)3 and CA) except for CP were homogeneously mixed in the reactor, CP was added to the system to initiate TCE degradation. Sampling was conducted for TCE degradation or chloride anion production analysis at time intervals determined beforehand. Control tests were carried out in parallel without addition of CP. All experiments were performed twice and the mean values were reported. The standard deviations were also shown as error bars in each figure.

Chemical probe tests were conducted in accordance with TCE degradation procedure in which TCE was replaced with chemical probe compounds. NB and CT were selected as the probes of HO• and O2−• respectively. Ahmad et al. used NB as a probe for HO• in an activated persulfate system due to its high reactivity with HO• (kHO• = 3.9 × 109 M−1s−1) [19]. CT was used as a O2−• probe in previous studies owing to its low reactivity with HO• (kHO• < 2 × 106 M−1 s−1) but high reactivity with O2−• (ke− = 1.6 × 1010 M−1s−1) [20].

Free radical scavenging tests were conducted with the addition of free radical scavengers to the TCE degradation procedure to observe their impact on TCE degradation. According to the previous study of Buxton et al., IPA reacts with HO• at high rates (kHO• = 1.9 × 109 M−1 s−1), whereas CF is highly reactive with O2−• (ke− = 3.0 × 1010 M−1 s−1) [4]. Therefore, IPA and CF were selected as radical scavengers to scavenge HO• and O2−•, respectively.

The effect of pH on TCE degradation for the CP/Fe(III)/CA system was investigated at pHs of 6, 7, and 8. Solution pH was maintained with phosphate buffer (0.1 mol·L−1) and pH values varied within 0.1 units during the experiments. The impact of the solution matrix on TCE degradation was investigated in separated tests wherein NaCl, NaHCO3, and HA were added individually to the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. An additional experiment was conducted using real groundwater, wherein all solutions were prepared with groundwater rather than ultrapure water. All other procedures were in accordance with TCE degradation in ultrapure water.

TCE degradation by CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA could be described by the pseudo-first-order kinetic model. According to the pseudo-first-order kinetic, reaction rate is linearly dependent on the concentration of contaminant as follows:

| (7) |

which could be further modified as:

| (8) |

where C0 is the initial TCE concentration (mmol·L−1); Ci is the TCE concentration at time t (mmol·L−1); kobs is the pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant (min−1).

2.3. Analytical methods

Aqueous samples (1.0 mL) containing TCE, CT, or NB were extracted with n-hexane (1.0 mL) for gas chromatograph (GC) analysis. The average extraction recovery rates of TCE, CT, and NB are 89.7%, 87.5%, and 93.1%, and the relative standard deviations are 3.1%, 1.9% and 1.2%, respectively. The organic phase was injected to a gas chromatograph for quantification (Agilent 7890A, Palo Alto, CA, USA). DB-VRX column (60 m length, 250 μm i.d., and 1.4 μm thickness) and electron capture detector (ECD) was used for detection of TCE and CT while the temperatures of the injector, detector and oven were set at 240, 260 and 75°C respectively. HP-5 column (30 m length, 250 μm i.d., and 0.25 μm thickness) and flame ionization detector (FID) were used to quantify NB while the injector, detector and oven temperatures were 250, 300 and 175°C, respectively. The detection limit of the above method for TCE is 1 μg·L−1, and the linear range is 0.1–25 mg·L−1, with a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.9992. Chloride anions released from TCE were analyzed by ion chromatography (Dionex ICS-I000, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Soluble ferric ion (Fe(III)) in aqueous solution was reduced to ferrous ion (Fe(II)) by hydroxylamine chloride and then determined with the 1,10-phenanthroline method [21]. H2O2 concentration in aqueous solution was quantified spectrophotometrically with the titanium sulfate method [22].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. TCE degradation performance in CP/Fe(III) system

The degradation of TCE by CP activated with Fe(III) is presented in Fig. 1. The experiments were carried out with fixed TCE concentration (0.15 mmol·L−1) at various CP/Fe(III)/TCE molar ratios from 4/8/1 to 20/40/1, corresponding to the initial pH values of 3.1, 3.0 and 2.8 in these conditions. The fixed initial CP/Fe(III) molar ratio of 1/2 was based on our previous study for the CP/Fe(II) system [18]. The control test without CP addition showed 5.2% loss of TCE due to volatilization, as shown in Fig. 1. Approximately 20%, 47% and 96% of TCE was degraded in 180 min at the CP/Fe(III)/TCE molar ratios of 4/8/1, 10/20/1, and 20/40/1, respectively, indicating that TCE could be effectively degraded when appropriate dosages of CP and Fe(III) were applied.

Fig. 1.

TCE degradation in CP/Fe(III) system at various CP/Fe(III)/TCE molar ratios ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1)

TCE degradation was adequately described by the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, and kobs values are summarized in Table S1. The kobs increased from 0.001 to 0.003 and 0.017 min−1 when the CP/Fe(III)/TCE molar ratios changed from 4/8/1 to 10/20/1 and 20/40/1, respectively.

Comparison of the results presented in Figure 1 for the CP/Fe(III) system to the results obtained from our previous study using Fe(II)-catalyzed CP [18] shows that TCE degradation was much slower for the CP/Fe(III) system. The rate-determining step in the CP/Fe(III) system was deduced to be the transformation of Fe(III) to Fe(II) (Eq. 2), which is particularly slow. The considerable distinction in the rate constants of Eq. 1 and Eq. 2 resulted in the huge variation between the degradation rates of TCE in the CP/Fe(II) and CP/Fe(III) systems. This resulted in a much higher dosage of CP and Fe(III) required to achieve efficient TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III) system due to the relatively low catalytic activity of Fe(III). However, compared to the CP/Fe(II) system, the reaction rate in the CP/Fe(III) system was slower, which prevented the rapid consumption of oxidants and accumulation of heat. The extended the duration of TCE degradation for the CP/Fe(III) system, which is an advantage of the CP/Fe(III) system. In the following section, the use of CA to improve the efficiency of Fe(III)-catalyzed CP and enhance TCE degradation is investigated.

3.2. TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system

The impact of CA on TCE degradation was investigated by testing different concentrations of CA for a fixed CP/Fe(III)/TCE molar ratio of 4/8/1 (see Fig. 2). It was observed that the magnitudes of TCE degradation increased from 20% to 63%, 99.9%, 99.7%, and 80% with the increase of CA dosage from 0 to 0.15, 0.30, 0.60, and 1.20 mmol·L−1, respectively (the CP/Fe(III)/CA/TCE molar ratio varied from 4/8/0/1 to 4/8/1/1, 4/8/2/1, 4/8/4/1 and 4/8/8/1, respectively). The results for the 1.2 mmol·L−1 treatment indicate that TCE degradation was less effective at the highest CA dose. The rate constants obtained from a pseudo-first-order kinetic model are presented in Table S1. kobs varied from 0.001 min−1 to 0.006, 0.053, 0.045 and 0.009 min−1 respectively in the presence of CA from 0 to 1.20 mmol·L−1. The results demonstrate that TCE degradation by the Fe(III) activated CP system was enhanced in the presence of CA. This is consistent with the previous study of Vicente in Fenton-like process [23].

Fig. 2.

Effect of CA dosage on TCE degradation in CP/Fe(III)/CA system ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1, [CP]0 = 0.60 mmol·L−1, [Fe(III)]0 = 1.20 mmol·L−1)

The solution pH dropped from 3.15 to 3.02, 2.86, 2.54 and 2.35 in the presence of 0.15, 0.30, 0.60, and 1.20 mmol·L−1 CA, respectively. The decrease in solution pH may have promoted the dissolution of CP, which would benefit the CP/Fe(III) system. Conversely, the positive effect of CA in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system could be explained by the chelation of Fe(III) by CA, which would enhance the stability of Fe(III) in solution. Xu et al. reported that CA could chelate metal ions to form soluble complexes that could catalyze Fenton oxidation [24]. There are three carboxyl groups and one hydroxyl group available in the CA structure, therefore CA is considered as having four dissociable protons in the dissociation process. The equilibrium reactions of citrate and Fe(III) and hydrolysis reactions of Fe(III) are given in Eqs. 9–18, where L represents citrate and Fe3+ is free ferric ion [6].

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

The mass balances of Fe(III) and citrate can be ascribed as Eqs. 19–20, where [Fe(III)]t and [L]t represent the total concentration of Fe(III) and citrate in solution respectively:

| (19) |

| (20) |

According to the pH values measured and the equilibrium constants for various reactions, the distribution of Fe(III)-CA in the presence of different CA dosages were calculated with Eqs. 19–20. The results in Table S2 demonstrate that the main species was free Fe3+, Fe(III)(OH)2+ and Fe(III)(OH)2+ in the absence of CA. While in the presence of CA, the hydrolysis reactions of Fe(III) were inhibited, and Fe(III)(OH)2+ and Fe(III)(OH)2+ species converted to chelated Fe(III) species (i.e. Fe(III)L− and Fe(III)HL) gradually. As CA concentration increased to 1.20 mmol·L−1, approximately 94% of Fe(III) was present as chelated species.

As noted above, the addition of 1.20 mmol·L−1 CA decreased the efficiency of TCE degradation. It was speculated that excess CA in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system competed with TCE to scavenge HO• and induced lower TCE degradation rate according to the previous study of Xue et al. [25]. In addition, excess chelate reduced the availability of Fe(II) and Fe(III), which diminished the generation of free radicals in a modified Fenton reaction [9]. This is consistent with the calculated speciation results discussed above, wherein 94% of Fe(III) was predicted to be chelated at 1.2 mmol·L−1 of CA. Consequently, an optimum molar ratio of Fe(III) and CA was obtained as 4/1 in this study.

The concentrations of Fe(III) and H2O2 in solution were measured to illustrate the enhanced effect of CA. With the addition of CP and the generation of Ca(OH)2, soluble Fe(III) precipitated to Fe(OH)3 gradually and the concentration decreased significantly to 0.34 mmol·L−1 within the initial 10 min in the absence of CA. The presence of CA (0.30 mmol·L−1) in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system prevented the precipitation of Fe(III) and the concentration of soluble Fe(III) in solution was elevated to over 1.0 mmol·L−1 for the entire reaction period.

Fig. 3 shows the generation of H2O2 due to CP dissolution, its increase and then its decomposition in the absence and presence of CA. The concentration of H2O2 increased in the initial 15 min, then H2O2 decomposed very slowly for the remainder of the test period in the CP/Fe(III) system. The presence of CA increased the dissolution rate of CP, as shown in Fig. 3, wherein the concentration of H2O2 increased to 0.55 mmol·L−1 at 10 min compared to the CP/Fe(III) system. This could be due to the decline of solution pH by adding CA. The initial solution pH decreased from 3.15 in the CP/Fe(III) system to 2.86 in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. After 10 min, CP transformed to H2O2 completely, and H2O2 decomposed along with the degradation of TCE to 0.06 mmol·L−1 at 90 min. These results demonstrate that the addition of CA improved the efficiencies of both Fe(III) and CP in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system.

Fig. 3.

Variations of H2O2 in CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1, [CP]0 = 0.60 mmol·L−1, [Fe(III)]0 = 1.20 mmol·L−1, [CA]0= 0.30 mmol·L−1)

3.3. Free radicals generated in CP/Fe(III)/CA system

3.3.1. Identification of radicals with chemical probes

Chemical probe tests were conducted to identify the primary radicals for the CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the degradation of NB reflects the continuous generation of HO• for both the CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems. However, only 20% removal of NB was observed within 120 min for the CP/Fe(III) system while NB was almost completely degraded for the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. The pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant of NB degradation increased over 23 fold (from 0.002 min−1 to 0.039 min−1) in the presence of CA. Gautier-Luneau et al. achieved similar results in Fenton-like chemistry with spin trapping methods [26].

Fig. 4.

Degradation of probe compounds in CP/Fe(III)/CA system ([NB]0 = 0.30 mmol·L−1, [CT]0 = 0.01 mmol·L−1, [CP]0 = 0.60 mmol·L−1, [Fe(III)]0 = 1.20 mmol·L−1, [CA]0= 0.30 mmol·L−1)

The presence of O2−• in the CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems was assessed using CT as a chemical probe (Fig. 4(b)). Approximately 19% and 22% declines in CT concentration were observed for the CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems, respectively, which demonstrated the generation of O2−• in both systems. However, no significant positive effect on O2−• generation was found with the addition of CA. O2−• was reported as a common product from the reaction between HO• and organic compounds in the Fenton-like process [27]. In our previous study, O2−• has been proven to be generated in the CP/Fe(II) system and promoted the degradation of TCE. Ma et al. also found that both HO• and O2−• existed on the surface of CaO2 suspension and confirmed the results with chemiluminescence [28].

Based on the discussion above, it was concluded that CP dissolved in solution to yield H2O2 (Eq. 6) and the generated H2O2 reacted with Fe(III) spontaneously which led to the formation of Fe(II) (Eq. 2) in both the CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems. As a consequence, HO• and O2−• were generated through modified Fenton-like reactions (Eqs. 3–5).

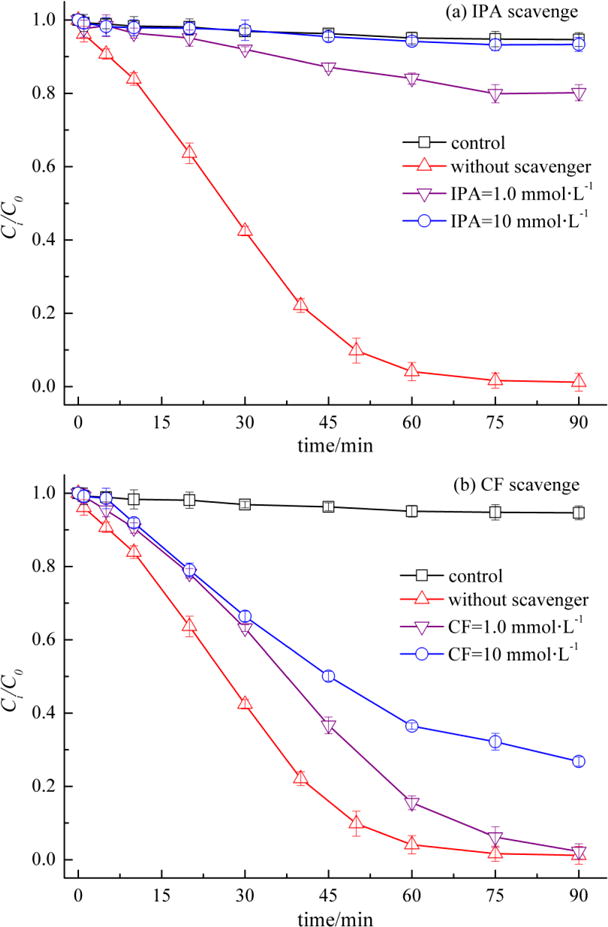

3.3.2 Free radical scavenging tests

Free radical scavenging tests were conducted to verify the contribution of HO• and O2−• to TCE degradation. As shown in Fig. 5(a), a significant reduction in TCE degradation was observed in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system amended with the addition of IPA. In the absence of IPA, TCE was completely degraded in 90 min. With the addition of 1.0 and 10 mmol·L−1 IPA, TCE degradation efficiencies within 90 min deceased greatly to 19.8% and 6.7%, respectively. As the concentration of IPA was much higher than that of TCE, HO• generated in the system was scavenged by IPA effectively. The decline in TCE degradation elucidated that TCE degradation was caused predominantly by the strong oxidation activity of HO•, and HO• was identified as the dominant radical responsible for TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. IPA was also used as a HO• scavenger by Northup and Cassidy in a CP system activated with EDTA chelated Fe(III) and results consistent to those reported herein were achieved [14].

Fig. 5.

Effect of radical scavengers on TCE degradation in CP/Fe(III)/CA system ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1, [CP]0 = 0.60 mmol·L−1, [Fe(III)]0 = 1.20 mmol·L−1, [CA]0= 0.30 mmol·L−1)

TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system in the presence of CF is shown in Fig. 5(b). As can be seen, the degradation efficiencies of TCE were decreased from 99.9% to 97.7% and 73.2% respectively with the addition of 1.0 and 10 mmol·L−1 CF. When the CF added increased to 10 mmol·L−1, an obvious inhibition for TCE degradation was observed. The scavenging effect of CF demonstrated that the presence of O2−• in the CP/Fe(III)CA system contributed to the degradation of TCE. HO• was mainly responsible for TCE degradation, according to the results presented in Fig. 5(a). However, it is speculated that O2−• actually participated in the transformation of Fe(III) to Fe(II), which was of vital importance to the generation of HO•, as shown in Eqs. 21–22. The second order reaction rate constant between O2−• and CF (ke−,CF = 3.0 × 1010 M−1 s−1) is much higher than that between O2−• and Fe(III) (k = 5×107 M−1 S−1) [29]. The scavenging effect of O2−• by CF resulted in a reduction in Fe(II) regeneration.

| (21) |

| (22) |

3.4. Effect of solution matrix and pH on TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system

Given the ubiquitous existence of Cl−, HCO3−, and HA in groundwater, the influences of these constituents at different concentrations on TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system were investigated separately and the results are shown in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6(a), Cl− showed an obvious inhibitive effect on TCE degradation for the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. With the increase of Cl− concentration from 0 to 100 mmol·L−1, TCE degradation efficiency decreased from 99.9% to 39.2%. This inhibition can be ascribed to the reaction between Cl− and HO• which resulted in a scavenging effect, as shown in Eqs. 23–24 [30].

| (23) |

| (24) |

Fig. 6.

Effect of solution matrix on TCE degradation ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1, [CP]0 = 0.60 mmol·L−1, [Fe(III)]0 = 1.20 mmol·L−1, [CA]0= 0.30 mmol·L−1)

Fig. 6(b) shows the influence of HCO3− on TCE degradation. The increase of HCO3− concentrations from 0 to 1.0, 10, and 100 mmol·L−1 led to decreases in TCE degradation efficiency from 99.9% to 95.1%, 27.3%, and 16.5%, respectively. The addition of HCO3− elevated solution pH from 2.86 to 3.16, 6.78, and 7.92 respectively in the presence of 1.0, 10 and 100 mmol·L−1 HCO3−. High pH inhibited the dissolution of CaO2 and promoted the precipitation of Fe(III), both of which are adverse to TCE degradation. Moreover, HCO3− could perform as a scavenger of HO•, as shown in Eqs. 25–26 [30]. HCO3− converted to CO32− which had a higher reactivity with HO• in high pH, and therefore the scavenging effect was enhanced.

| (25) |

| (26) |

HA, a widely existing macromolecular organic substance in the natural environment was used as a model to investigate the influence of natural organic matter on TCE degradation. Fig. 6(c) shows that HA concentrations of 1.0 and 10 mg·L−1 had minimal impact while 100 mg·L−1 HA had a minor inhibition on TCE degradation. Wang and Lemley studied the effect of HA on alachlor degradation by an anodic Fenton process and the results showed the competition of HA with alachlor for HO• which slowed down the rate of alachlor degradation significantly [31]. It suggested that the negative effect of high HA concentration should not be neglected in the application of CP/Fe(III)/CA system to actual groundwater remediation.

The effect of solution pH on TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system was evaluated and the results are shown in Fig. S1. The results indicate that TCE degradation efficiency decreased with pH increasing from 6 to 8. TCE was almost completely degraded at 90 min without phosphate buffer at pH 3.15. In contrast, only 52.9%, 27.8%, and 11.8% of TCE was degraded at 90 min at pH values of 6, 7, and 8, respectively. It is demonstrated that acid pH condition was favorable for TCE degradation and that a pH increase slowed TCE degradation in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. It was speculated that with the increase of solution pH, the complexation between Fe(III) and CA became more unstable, leading to the decrease of soluble iron.

3.5. Tests of the CP/Fe(III)/CA system in groundwater

Fig. 7 shows the comparison of TCE degradation performance in ultrapure water versus groundwater. It can be seen that TCE degradation was inhibited in groundwater compared with that in ultrapure water, with 30% degraded in 180 min for groundwater versus complete degradation in ultrapure water. The presence of Cl−, HCO3−, and organic matter was confirmed in the groundwater (Table S3). Cl− and HCO3− were speculated to inhibit TCE degradation and the organic matter would compete with TCE for oxidants as noted before in Section 3.4. However, TCE degradation efficiency increased to 54.9% and 99.7% with increasing CP/Fe(III)/CA/TCE molar ratio from 4/8/2/1 to 8/16/4/1 and 16/32/8/1, suggesting that the inhibition caused by solution matrix could be overcome by increasing the reagent dosages. From the above results, it is clear that the application of CP/Fe(III)/CA technology is practicable for contaminated groundwater remediation but that the solution matrix plays an important role in the TCE degradation performance. Therefore, the characteristics of groundwater should be taken into consideration when CP/Fe(III)/CA technology is applied for in situ applications.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of TCE degradation in ultrapure water and real groundwater ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1)

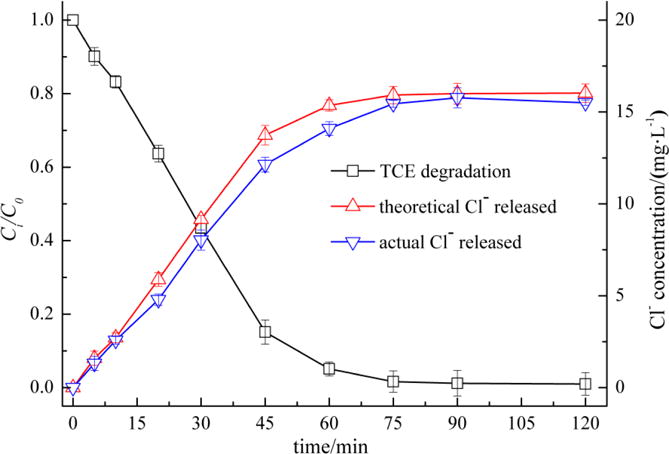

3.6. Chloride liberation in CP/Fe(III)/CA system

Chloride ions (Cl−) released from TCE were monitored in parallel with TCE degradation to confirm the dechlorination efficiency of TCE in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. Based on the molecular formula of C2HCl3, 3.0 mol·Cl− would be produced from 1.0 mol TCE in the case of complete dechlorination. The theoretical Cl− release was calculated according to TCE degradation efficiency and compared with the measured Cl− in solution. As shown in Fig. 8, the measured Cl− released was slightly less than the theoretical value within 90 min. Hence, the dechlorination of TCE was incomplete during the reaction and some chlorinated intermediates were likely produced. At 90 minutes the measured concentration of Cl− matched the theoretical value of 16 mg·L−1. These results demonstrate that any chlorinated intermediates that may have been produced were degraded quickly and TCE was completely mineralized in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system. Chen et al. also found that TCE in groundwater and soil slurries was completely dechlorinated and no chlorinated intermediates were found in the Fenton oxidation process [32].

Fig. 8.

Cl− production in CP/Fe(III)/CA system along with TCE degradation ([TCE]0 = 0.15 mmol·L−1, [CP]0 = 0.60 mmol·L−1, [Fe(III)]0 = 1.20 mmol·L−1, [CA]0= 0.30 mmol·L−1)

As discussed in previous sections, HO• was the predominant radical responsible for TCE degradation. The high reaction rate constant between HO• and TCE (kTCE = 4 ×109 M−1S−1) indicated that TCE could be easily attacked by HO• and transformed in the CP/Fe(III)/CA system [33]. The pathway of TCE degradation was speculated as follows according to the results reported in the literature. The double bond of TCE was attacked by HO• initially and TCE transformed to chlorinated intermediates such as dichloroacetic and trichloroacetic acids generally along with the release of Cl− [34]. These intermediates were dechlorinated further to organic acids such as glyoxylic acid and formic acid, and finally mineralized to CO2 and H2O [35].

4. Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of CA on enhancing TCE degradation by CP activated with Fe(III). TCE was effectively degraded in the CP/Fe(III) system with appropriate dosages of CP and Fe(III). The presence of CA elevated soluble Fe(III) concentration and promoted H2O2 generation in solution, resulting in significant improvement in TCE degradation. TCE degradation in both CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems followed a pseudo first order kinetic model. The generation of HO• and O2−• in CP/Fe(III) and CP/Fe(III)/CA systems was confirmed with chemical probes. Meanwhile, free radical scavenging tests verified that HO• was the dominant radical that contributed to TCE degradation and O2−• promoted TCE degradation by participating in HO• generation. To some extent, solution matrix including Cl−, HCO3− and HA and increasing pH showed various inhibition effects on TCE degradation. Tests using groundwater indicated that CP/Fe(III)/CA technology was practicable for contaminated groundwater remediation with use of higher reagent doses. The measured Cl− released along with TCE removal suggested that the degraded TCE was completely dechlorinated. In summary, the findings in this study strongly support the prospect of using CA to enhance Fe(III)-activated CP in situ for remediation of TCE-contaminated groundwater.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.41373094 and No.51208199), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M570341) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (22A201514057). The contributions of Dr. Mark Brusseau were supported by the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (P42 ES04940).

References

- 1.Yaron B, Dror I, Berkowitz B. Soil-Subsurface Change. Berlin: Springer; 2012. Properties and Behavior of Selected Inorganic and Organometallic Contaminants; pp. 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Environmental Protection Agency. TSCA Work Plan Chemicals: Methods Document. 2012 Available online at http://www.epa.gov/oppt/existingchemicals/pubs/wpmethods.pdf (accessed August 21, 2015)

- 3.Pignatello JJ, Oliveros E, MacKay A. Advanced oxidation processes for organic contaminant destruction based on the Fenton reaction and related chemistry. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 2006;36(1):1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O−) in aqueous solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1988;17(2):513–886. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Luca A, Dantas RF, Esplugas S. Assessment of iron chelates efficiency for photo-Fenton at neutral pH. Water Research. 2014;61:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li YC, Bachas LG, Bhattacharyya D. Kinetics studies of trichlorophenol destruction by chelate-based Fenton reaction. Environmental Engineering Science. 2005;22(6):756–771. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun SP, Zeng X, Lemley AT. Kinetics and mechanism of carbamazepine degradation by a modified Fenton-like reaction with ferric-nitrilotriacetate complexes. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2013:252–253. 155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ström L, Owen AG, Godbold DL, Jones DL. Organic acid behaviour in a calcareous soil: sorption reactions and biodegradation rates. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2001;33(15):2125–2133. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seol Y, Javandel I. Citric acid-modified Fenton’s reaction for the oxidation of chlorinated ethylenes in soil solution systems. Chemosphere. 2008;72(4):537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thayer PS, Kensler CJ, Rall D. Current status of the environmental and human safety aspects of nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 1973;3(1–4):375–404. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen J, Stacey SP, McLaughlin MJ, Kirby JK. Biodegradation of rhamnolipid, EDTA and citric acid in cadmium and zinc contaminated soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2009;41(10):2214–2221. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang C, Bruell CJ, Marley MC, Sperry KL. Persulfate oxidation for in situ remediation of TCE. II. Activated by chelated ferrous ion. Chemosphere. 2004;55(9):1225–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis S, Lynch A, Bachas L, Hampson S, Ormsbee L, Bhattacharyya1 D. Chelate-modified Fenton reaction for the degradation of trichloroethene in aqueous and two-phase systems. Environmental Engineering Science. 2009;26(4):849–859. doi: 10.1089/ees.2008.0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Northup A, Cassidy D. Calcium peroxide (CaO2) for use in modified Fenton chemistry. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2008;152(3):1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian Y, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Chen J. Performance and properties of nanoscale calcium peroxide for toluene removal. Chemosphere. 2013;91(5):717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goi A, Viisimaa M, Trapido M, Munter R. Polychlorinated biphenyls-containing electrical insulating oil contaminated soil treatment with calcium and magnesium peroxides. Chemosphere. 2011;82(8):1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang A, Wang J, Li Y. Performance of calcium peroxide for removal of endocrine-disrupting compounds in waste activated sludge and promotion of sludge solubilization. Water Research. 2015;71:125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Gu X, Lu S, Miao Z, Xu M, Fu X, Qiu Z, Sui Q. Degradation of trichloroethene in aqueous solution by calcium peroxide activated with ferrous ion. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2015;284:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad M, Teel AL, Furman OS, Reed JI, Watts RJ. Oxidative and reductive pathways in iron-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid–activated persulfate systems. Journal of Environmental Engineering. 2011;138(4):411–418. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang C, Su HW. Identification of sulfate and hydroxyl radicals in thermally activated persulfate. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 2009;48(11):5558–5562. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura H, Goto K, Yotsuyanagi T, Nagayama M. Spectrophotometric determination of iron (II) with 1, 10-phenanthroline in the presence of large amounts of iron (III) Talanta. 1974;21(4):314–318. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(74)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen IR, Purcell TC, Altshuller AP. Analysis of the oxidant in photooxidation reactions. Environmental Science & Technology. 1967;1(3):247–252. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicente F, Rosas J, Santos A, Romero A. Improvement soil remediation by using stabilizers and chelating agents in a Fenton-like process. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2011;172(2):689–697. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J, Xin L, Huang T, Chang K. Enhanced bioremediation of oil contaminated soil by graded modified Fenton oxidation. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2011;23(11):1873–1879. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(10)60654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue X, Hanna K, Despas C, Wu F, Deng N. Effect of chelating agent on the oxidation rate of PCP in the magnetite/H2O2 system at neutral pH. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical. 2009;311(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gautier-Luneau I, Bertet P, Jeunet A, Serratrice G, Pierre JL. Iron-citrate complexes and free radicals generation: Is citric acid an innocent additive in foods and drinks? BioMetals. 2007;20(5):793–796. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voelker BM, Sulzberger B. Effects of fulvic acid on Fe(II) oxidation by hydrogen peroxide. Environmental Science & Technology. 1996;30(4):1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, Zhang BT, Zhao L, Guo G, Lin JM. Study on the generation mechanism of reactive oxygen species on calcium peroxide by chemiluminescence and UV-visible spectra. Luminescence. 2007;22(6):575–580. doi: 10.1002/bio.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Laat J, Le TG. Kinetics and modeling of the Fe(III)/H2O2 system in the presence of sulfate in acidic aqueous solutions. Environmental Science & Technology. 2005;39(6):1811–1818. doi: 10.1021/es0493648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao CH, Kang SF, Wu FA. Hydroxyl radical scavenging role of chloride and bicarbonate ions in the H2O2/UV process. Chemosphere. 2001;44(5):1193–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q, Lemley AT. Kinetic effect of humic acid on alachlor degradation by anodic Fenton treatment. Journal of Environmental Quality. 2004;33(6):2343–2352. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen G, Hoag GE, Chedda P, Nadim F, Woody BA, Dobbs GM. The mechanism and applicability of in situ oxidation of trichloroethene with Fenton’s reagent. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2001;87(1):171–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(01)00263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiang Z, Ben W, Huang CP. Fenton process for degradation of selected chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons exemplified by trichloroethene, 1,1-dichloroethylene and chloroform. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering in China. 2008;2(4):397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis S, Lynch A, Bachas L, Hampson S, Ormsbee L, Bhattacharyya D. Chelate-modified Fenton reaction for the degradation of trichloroethene in aqueous and two-phase systems. Environmental Engineering Science. 2009;26(4):849–859. doi: 10.1089/ees.2008.0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li K, Stefan MI, Crittenden JC. Trichloroethene degradation by UV/H2O2 advanced oxidation process: product study and kinetic modeling. Environmental Science & Technology. 2007;41(5):1696–1703. doi: 10.1021/es0607638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.