Abstract

Background

Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) is one of the highest reported infectious diseases with several outbreaks across the world. This study aimed at describing epidemiological characteristics, investigating spatio-temporal clustering changes, and identifying determinant factors in different clustering areas of HFMD.

Methods

Descriptive statistics was used to evaluate the epidemic characteristics of HFMD from 2009 to 2015. Spatial autocorrelation and spatio-temporal cluster analysis were used to explore the spatial temporal patterns. An autologistic regression model was employed to explore determinants of HFMD clustering.

Results

The incidence rates of HFMD ranged from 54.31/10 million to 318.06/10 million between 2009 and 2015 in Hunan. Cases were mainly prevalent in children aged 5 years and even younger, with an average male-to-female sex ratio of 1.66, and two epidemic periods in each year. Clustering areas gathered in the northern regions in 2009 and in the central regions from 2010 to 2012. They moved to central-southern regions in 2013 and 2014 and central-western regions in 2015. The significant risk factors of HFMD clusters were rainfall (OR = 2.187), temperature (OR = 4.329) and humidity (OR = 2.070). The protect factor was wind speed (OR = 0.258).

Conclusions

The HFMD incidence from 2009 to 2015 in Hunan showed a new spatiotemporal clustering tendency, with the shifting trend of clustering areas toward south and west. Meteorological factors showed a strong association with HFMD clustering, which may assist in predicting future spatial-temporal clusters.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-017-2742-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: HFMD, Spatial autocorrelation, Spatio-temporal analysis, Tendency analysis, Autologistic regression model, Determinants

Background

Hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) is a highly contagious disease caused mainly by human enterovirus 71 (EV71) and coxsackievirus A16 (CoxA16), [1]. Although the infection is typically mild and self-limiting, infants and children, especially those under 5 years old are at greatest risk of severe disease affecting the central nervous system [2]. Currently, there are no available vaccines, chemoprophylaxis and effective anti-virus therapies for dealing with HFMD [3, 4].

The past decades have witnessed several outbreaks of HFMD across the world, affecting millions of people in countries such as Bulgaria, Australia, Japan, and Vietnam [5–8]. In March 2008, a nation-wide epidemic of HFMD started in Fuyang City, Anhui Province, China, recording 6049 cases and 22 deaths [9]. In view of these influences, HFMD has been listed as a reportable disease by the Chinese Ministry of Health to facilitate better disease prevention and control. Surveillance data shows that over 7.2 million cases and 2457 fatal cases were reported in China between 2009 and 2012, making HFMD the top reportable disease in China during the period under review [10].

Many studies showed that some climatic factors were associated with HFMD infection. By using a time series analysis, Huang et al. found that temperature and relative humidity were statistically related to HFMD occurrence [11]. However, a study carried out by Li et al. showed atmospheric pressure having a negative relationship with HFMD incidence in Guangzhou city [12]. Although several spatial analyses on HFMD prevalence have been conducted, only few studies have focused their analyses on determinant factors which attributed to HFMD spatio-temporal clusters [13–15]. Most studies only described the spatial patterns and cluster locations of cases. The objective of our study was to map county-level epidemiological characteristics and spatio-temporal distribution of HFMD incidence and to explore the determinants of HFMD in different clustering areas. Findings of the study were to guide the allocation of public health resources to maximize cost-effectiveness in the prevention and control of HFMD epidemics.

Methods

Study area

Hunan province is one of the central inland provinces of China situated between 108°47′ to 114°15′ east longitude and 24°38′ to 30°08′ north latitude with a typically subtropical monsoon climate. Hunan, with a population of approximately 67.8 million, covers an area of about 211,800 km2, and has 14 districts and 124 counties. High humidity, abundant heat, high population density and high levels of migration promote the development and spread of enteroviruses within the Province.

Data description

Surveillance data on HFMD in Hunan was obtained from the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.chinacdc.cn). This data covered the study period (2009 to 2015), and included case types as well as pathogen types (only for laboratory diagnosed cases) for all the new cases identified during the study period. The diagnostic criteria were based on the 2010 HFMD Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Cases without home addresses, clinical or laboratory diagnosis information were excluded from the study. Meteorological data was obtained from the Hunan Meteorological Administration. The Hunan map at county level was also provided by the Information department of the China Disease Control and Prevention Center.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Spatial autocorrelation is defined as the spatial dependence among the given attribute value of one geographic unit and its neighboring units, which lies in almost all spatial observations [16]. Global spatial autocorrelation is used to measure the overall clustering tendency in the study region while the local one can be further used to clarify the patterns and the exact location of the clusters among local counties [17–19]. In this study, we used global Moran’s I statistic and local indicators of spatial autocorrelation (LISA) to investigate spatial association regarding incidence of HFMD in the Hunan province [20].

The global Moran’s I statistic ranges from −1 to 1. An I > 0 indicates positive autocorrelation and the closer it is to 1, the more aggregated the distribution is. An I < 0 indicates negative autocorrelation and the closer it is to −1, the more dispersed the distribution is. An I = 0 indicates no autocorrelation, suggesting that the disease is randomly distributed. The significance of Moran’s I is assessed by Monte Carlo test using Z statistic and P value (Z ≥ 1.96 or Z ≤ −1.96 indicates statistical significance at the 5% level) [21]. By using the LISA map, four patterns of spatial correlation can be detected: high-high clusters; low-low clusters; high-low clusters; and low-high clusters [22]. In reality, the high-high clusters (i.e. high-incidence districts surrounded by other high-incidence districts) are the most important patterns for the purpose of disease prevention and control.

The formula for global or local Moran’s I is:

Where n is the number of districts or counties; x i and x j are the incidence rates in districts or counties i and j; is the average incidence rate in the entire study area; and w ij is the spatial weight between districts or counties i and j. In this study, by choosing the binary spatial weight matrix in Rook contiguity rule [23], Geoda 1.6 software was used for the spatial autocorrelation analysis whilst ArcGis 10.2 software was used to visualize the results.

Spatio-temporal cluster analysis

Kulldorff’s method of retrospective space-time scan statistic was used to detect the geographical clusters of HFMD cases at the county level based on a discrete Poisson model [24]. In this approach, a dynamic cylindrical window was used to scan for different time and geographic area to detect all possible clusters. The circular geographic base moves with the radius varying with the population range of the area, while the height varying with the defined time interval [25]. For each scanning, the relative risk (RR) is calculated using the ratio of the observed case number to the expected case number within and outside the windows as well as the log likelihood ratio (LRR). The P values for clusters detected are calculated by Monte Carlo randomization method [26, 27]. The window with the maximum LLR is assumed to be the most likely cluster, and other windows with a statistically significant LLR are defined as secondary clusters ranked according to their LLR value.

The LLR for a given window can be calculated as follows:

Where N is the total number of cases; n is the observed number of cases within the scan window; E(n) and N − E(n) are the expected number of cases within and outside the scan window under the null hypothesis (H0: The spatio-temporal clustering of the study area are caused by random factors.), respectively; and I ′is an indicator function. It is equal to 1 when the window has more cases than expected under the null hypothesis, otherwise it is 0. In space-time scan analysis, the spatial unit is county, with 124 counties in Hunan Province; the temporal unit is month, with 84 months from 2009 to 2015. The spatial size of scanning window was limited to 30% of the total population at risk whilst the temporal size was set to 30% of the total study period in order to scan for small to large clusters. The number of Monte Carlo randomization was set at 999. By setting the time frame of the scan analysis to be one month, we can control the time trends and observe the cluster changes in the entire study. SaTScan 9.4 software was used to perform the spatiotemporal cluster analysis of HFMD and ArcGis 10.2 software was used to visualize the results.

Autologistic regression model

Spatial autocorrelation is frequently present in the observations and it appears that neighboring units tend to have more similar value than those that are distributed randomly [28]. In considering spatial dependence, Besag et al. present the autologistic regression model which is a special type of ordinary logistic model introducing a spatial autocorrelation term (SAuto cov i) in the form of weighting coefficients [29]. Temporal autocorrelation commonly exists in infectious disease. In our study, we modified the autologistic regression by introducing TAuto cov i as the temporal autocovariate, which is set with the incidence cases of last month in the same county. Meanwhile, many previous studies have found that population density is significantly associated with HFMD occurrence [30, 31], so we introduced the population density cov i as the covariate to adjust for population density in different counties.

For the modified autologistic regression model, the form of the model is given by equation:

The probability of the occurrence of the outcome can be illustrated as follows:

where y i is the dependent variable which refers to the probability of spatiotemporal clusters occurrence, P i is the mean of y i, or equivalently, the probability of y i=1, and x denotes the exposure factors in meteorology (the temporal resolution of independent variables is one month which coincide with the time frame of the SaTScan analysis). cov i is the population density covariate. SAuto cov i, TAuto cov i are the spatial and temporal autocovariate, respectively. β, p, q and r are the regression coefficient. i is the index of the county.

SAuto cov i is the weighted average of the probabilities of the geographic unit i which is surrounded by other k i geographic units. w ij is the spatial weight between county i and j, and h ij is the Euclidean distance between the centroids of county i and j. P j is the probability of the event occurring in the neighbors of county i, which is equal to 1 when the event occurs, otherwise it is 0. In this study, P j refers to the probability of spatiotemporal clusters occurrence in neighboring county j of county i. A county with the distance within 31,250 m from county i was defined as the neighbors of county i [31]. (see Additional file 1: Table S1–1, Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the spatial autocorrelation test on HFMD incidence at county level in Hunan Province, 2009–2015

| Year | Moran’ I | S.E. | Z-score | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 0.374 | 0.045 | 8.31 | <0.001 |

| 2010 | 0.414 | 0.043 | 9.68 | <0.001 |

| 2011 | 0.449 | 0.043 | 10.40 | <0.001 |

| 2012 | 0.299 | 0.039 | 7.58 | <0.001 |

| 2013 | 0.278 | 0.043 | 6.44 | <0.001 |

| 2014 | 0.319 | 0.045 | 7.04 | <0.001 |

| 2015 | 0.362 | 0.045 | 8.01 | <0.001 |

In this study, after calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance to decrease multicollinearity (see Additional file 1: Table S3–1), five independent variables were selected: monthly average rainfall, monthly average temperature, monthly average wind speed, monthly average relative humidity, monthly total sunshine. We also introduced the population density as the covariate. All variables were standardized. A forward stepwise method was used in the ordinary logistic regression model. We then introduced the SAuto cov i and TAuto cov i until each variable was statistically significant. Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 were used to test the goodness of fit of logistic or autologistic model. The higher the statistic value are, the better the model fits the observations. We used the Relative Operating Characteristic (ROC) to compare the probability predicted by the model with the reality (the occurrence of the spatiotemporal clusters). Closer to 1 means a better fit, which rages from 0.5 to 1. SPSS 22.0 software was used to conduct the autologistc regression model and ArcGIS 10.2 software was used to perform spatial analysis.

Results

Epidemiological characteristics

There were 895,429 HFMD cases reported in Hunan Province from 2009 to 2015, with the average annual incidence rate of 194.57 per 100,000 (ranged from 54.31 per 100,000 in 2009 to 318.05 per 100,000 in 2014). Of the total cases, 8263 (0.92%) were severe and 352 (0.39‰) were death.

A total of 559,033 male cases and 336,396 female cases were reported during the study period and the male-to-female incidence ratio was 1.66:1 (ranged from 2.01:1 in 2009 to 1.53:1 in 2014). Most patients were younger than 5 years old, accounting for more than 90% of all reported cases. Scattered children have the highest incidence rate, followed by nursery children and school students. Among 30,377 laboratory confirmed cases, CoxA16, EV71 and other EV accounted for 16.67%, 47.62% and 35.72%, respectively. The predominant pathogen was EV71 in most years except for 2013 and 2015 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Epidemiological characteristics of HFMD cases in Hunan Province, 2009–2015

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| 0–5 year | 31,501 | 102,376 | 96,131 | 176,097 | 102,914 | 197,243 | 128,383 | 834,645 |

| >5 year | 3174 | 9821 | 6315 | 13,410 | 5288 | 15,549 | 7227 | 60,784 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 23,149 | 71,753 | 65,700 | 120,531 | 66,798 | 128,533 | 82,569 | 559,033 |

| Female | 11,526 | 40,444 | 36,746 | 68,976 | 41,404 | 84,259 | 53,041 | 336,396 |

| Sex ratio | 2.01:1 | 1.77:1 | 1.79:1 | 1.75:1 | 1.61:1 | 1.53:1 | 1.56:1 | 1.66:1 |

| Living condition | ||||||||

| Scattered children | 25,379 | 88,587 | 86,752 | 165,220 | 96,111 | 182,186 | 119,264 | 763,499 |

| Nursery children | 7957 | 19,124 | 12,847 | 18,668 | 9814 | 25,134 | 13,728 | 107,272 |

| School students | 1170 | 4045 | 2519 | 5180 | 2015 | 4929 | 2190 | 22,048 |

| Others | 169 | 441 | 328 | 439 | 262 | 543 | 428 | 2610 |

| Pathogen | ||||||||

| EV71 | 152 | 2520 | 1006 | 4510 | 1565 | 2675 | 2037 | 14,465 |

| CoxA16 | 140 | 655 | 1019 | 685 | 630 | 1595 | 537 | 5061 |

| Others | 112 | 1186 | 911 | 1689 | 2177 | 1811 | 2965 | 10,851 |

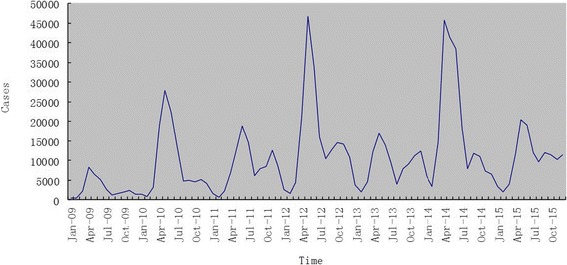

The monthly distribution of HFMD cases in Hunan is shown in Fig. 1, which indicates that the major peak appeared between April and July whilst the minor peak observed between September and November. The occurrence of HFMD shows significant seasonality with the wave-like increasing tendency.

Fig. 1.

The distribution of HFMD cases in month in Hunan Province, 2009–2015

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

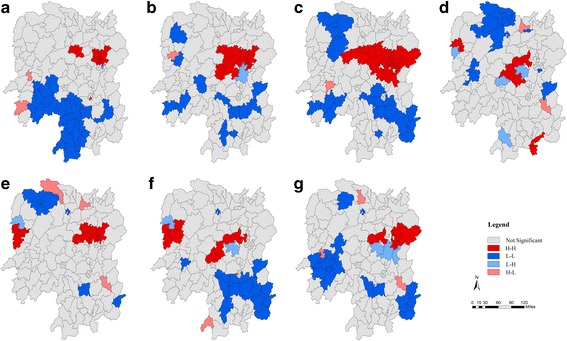

Global Moran’s I statistics was performed to investigate the presence of global autocorrelation, which were listed in Table 2. It clearly shows that the HFMD cases were not randomly distributed and that there was high global autocorrelation among HFMD number at county level in Hunan Province. The results of local autocorrelation analysis were mapped in Fig. 2. The LISA map shows that the high-high clusters (dark red color) were mostly in central and northern districts including Changsha, Yiyang, Loudi, Xiangtan, while southwestern districts of Hunan Province were low-low clusters (dark blue color). Nevertheless, contrary to other cities in western districts, Xiangxi showed a high-high pattern in the LISA map in recent years.

Fig. 2.

Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) maps for the incidence of HFMD in Hunan Province, 2009–2015 (a-g); H-H, high-high cluster; L-L, low-low cluster; L-H, low-high cluster; H-L, high-low cluster

Spatio-temporal cluster analysis

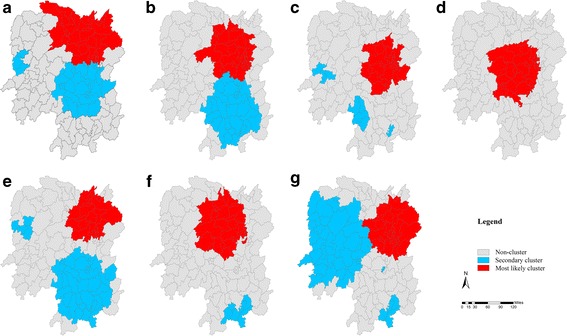

Table 3 and Fig. 3 show the scanning results of statistically significant spatial-temporal clusters of HFMD from 2009 to 2015. Seventeen (17) spatial-temporal clusters were detected each year during the study period, including 7 most likely clusters and 10 secondary clusters. All the clusters occurred in the period of the major peak of incidence except for 3 secondary clusters in 2011 and 2015. Clustering areas gathered in the northern regions in 2009, in the central regions from 2010 to 2012, moved to central-southern regions in 2013 and 2014, and central-western regions in 2015.

Table 3.

Results of the Spatio-temporal cluster test on HFMD incidence at county level in Hunan Province, 2009–2015

| Year | Cluster type | Cluster time | Radius (km)/Counties (n) | Cluster regions | RR | LLR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Most-likely | Apr 1-Jun 30 | 158.08 (32) | Northern | 5.33 | 7631.47 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | Apr 1-May 31 | 112.49 (33) | Central | 2.57 | 1231.69 | <0.001 | |

| 2010 | Most-likely | Apr 1-Jul 31 | 105.46 (31) | Central | 5.48 | 29,371.10 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | Apr 1-Jun 30 | 124.80 (30) | Central-southern | 2.80 | 2746.93 | <0.001 | |

| 2011 | Most-likely | May 1-Jul 31 | 96.49 (29) | Central-western | 4.27 | 14,620.54 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | Mar 1-Jul 31 | 45.44 (4) | Central | 2.75 | 1061.01 | <0.001 | |

| Secondary | Sep 1-Dec 31 | 29.03 (3) | Western | 2.29 | 354.38 | <0.001 | |

| 2012 | Most-likely | May 31-Jun 30 | 111.41 (32) | Central | 4.09 | 20,059.96 | <0.001 |

| 2013 | Most-likely | Apr 1-Jul 31 | 91.83 (23) | Central-northern | 2.54 | 5221.37 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | Apr 1-Jun 30 | 39.20 (4) | Western | 5.11 | 1603.22 | <0.001 | |

| Secondary | Apr 1-Jun 30 | 131.84 (36) | South-western | 1.72 | 1409.81 | <0.001 | |

| 2014 | Most-likely | Apr 1-Jun 30 | 117.38 (30) | Central | 4.40 | 33,910.07 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | May 1-Jun 30 | 74.22 (6) | Southern | 2.94 | 1540.24 | <0.001 | |

| 2015 | Most-likely | May 1-Jul 31 | 120.81 (30) | Central | 3.03 | 9577.40 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | May 1-Oct 30 | 11.38 (2) | Central | 4.04 | 1314.12 | <0.001 | |

| Secondary | May 1-Jun 30 | 170.72 (38) | Western | 1.58 | 762.17 | <0.001 | |

| Secondary | Apr 1-Jun 30 | 60.65 (4) | Southern | 2.38 | 568.19 | <0.001 |

Fig. 3.

Spatio-temporal clusters of HFMD in Hunan Province, 2009–2015 (a-g)

Autologistic regression model

Considering the spatial and temporal autocorrelation which existed in Hunan HFMD cases, this study introduced the auto covariates SAuto cov i and TAuto cov i on the basis of the ordinary logistic regression model (see Additional file 1: Table S1–4). The occurrence of the HFMD spatio-temporal cluster in the given county was the dependent variable (It is equal to 1 when the spatiotemporal cluster occurs, otherwise it is 0), while the selected exposure factors were the independent variables (they were continuous variables so should not to be assigned). Table 4 shows the results of the autologistic regression. The OR values for monthly average rainfall, monthly average temperature and monthly average relative humidity are all greater than 1, which indicates that these variables are risk factors that are positively related to the occurrence of HFMD spatial-temporal clusters. On the contrary, the OR value for monthly average wind speed is less than 1.

Table 4.

The OR values obtained from autologistic regression model

| Variables | β | S.E. | Wald χ 2 | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall (ml) | 0.783 | 0.163 | 23.053 | 2.187 (1.587 ~ 3.010) | 0.000 |

| Temperature (°C) | 1.465 | 0.319 | 21.046 | 4.329 (2.315 ~ 8.096) | 0.000 |

| Wind speed (m/s) | −1.356 | 0.240 | 31.969 | 0.258 (0.161 ~ 0.412) | 0.000 |

| Humidity (%) | 0.727 | 0.216 | 11.318 | 2.070 (1.355 ~ 3.162) | 0.001 |

| Cov i | 0.470 | 0.158 | 8.831 | 1.600 (1.174 ~ 2.181) | 0.003 |

| SAuto | 6.178 | 0.497 | 154.396 | 482.260 (181.984 ~ 1277.999) | 0.000 |

| TAuto | 0.006 | 0.001 | 22.036 | 1.006 (1.004 ~ 1.009) | 0.000 |

| Constant | −5.840 | 0.436 | 179.075 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

In addition, the goodness of the model was measured by the Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 statistics and the ROC value was used to compare the reality with the predicted outcome. All values were listed in Table 5 which indicated that the autologistic regression model had a better goodness of fit than the ordinary one.

Table 5.

The goodness of fit of the logistic and autologistic regression model

| Statistics | Logistic regression model | Autologistic regression model |

|---|---|---|

| Cox & Snell R2 | 0.254 | 0.428 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.475 | 0.802 |

| ROC | 0.913 | 0.983 |

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed that Hunan Province was one of the most serious HFMD epidemic areas in China with the average incidence rate of 194.57 per 100,000, which was much higher than the national average of 139.78 per 100,000 [32]. Furthermore, the incidence rate showed a rapidly increasing trend within the recent 4-year period, suggesting that the prevention and control of HFMD was still a major public health problem in the province. Scattered children under 5 years old accounted for more than 85% of all cases, and the incidence rate was especially high in the 1-year-old group, comparing well with previous reports [33, 34]. Poor immunity as well as a lack of available vaccines made it easier for children to succumb to HFMD viruses. Consistent with Deng’s reports [3], our study found that incidence rate among males was about 1.66 times greater than females, and this could be attributed to the fact that males spent more time engaged in outdoor activities thereby exposing them to pathogens.

Although EV71 and CoxA16 were still predominant in newly occurring HFMD cases around the world [35, 36], our study showed that other EV pathogens ranked first in the recent three-year period. Notably, some other reports have suggested that CoxA6, ECHO30 and CoxA10 were going to be the important causative agents for HFMD [37–39]. This means that surveillance systems should look out for new pathogenic strains alongside the regular EV61 and CoxA16 virus to prevent possible outbreaks associated with other new enteroviruses.

Our study showed significant seasonality in the incidence of HFMD (it peaked in April to July and September to November), similar to other studies conducted in Singapore [40] and Taiwan [41]. The first peak might be the result of the warm temperature, abundant rainfall and high atmospheric pressure during the season. Many children enter kindergarten in September thereby increasing the occurrence of the clustering of cases associated with the second minor peak. Thus, measures such as morning checks, case isolation and school closure should be implemented to reduce incidence and spread of HFMD during the high incidence period.

The global spatial autocorrelation analysis showed that the incidence of HFMD in Hunan during the 2009–2015 period was not randomly distributed at county level. The high-high clusters were aggregated in the provincial capital city, Changsha, and its neighboring areas, whereas some counties in rural areas such as Huaihua, Chenzhou and Yongzhou were low-low clusters in the LISA map. These hot spots were mainly located in areas with highly developed economy, high population density, and good health similar to the observations by Deng et al. [3]. Furthermore, spatiotemporal clusters of HFMD cases appeared annually during the study periods. Nearly all the clusters occurred in April to July, which was the same as the major peak of incidence of HFMD in Hunan. Consistent with most previous researches, the most likely clusters stayed almost the same in the urban areas [3, 42, 43], nevertheless the secondary clusters were diverse during the 2009–2015 period with a shifting trend toward the south and west. According to our study, the occurrence of HFMD spatiotemporal clusters is showing a new trend which needs further research to provide early warning signals for HFMD epidemics.

Although the effect of climatic factors on HFMD incidence has been revealed in many previous researches, there is few supporting studies about the effect of weather conditions on HFMD spatiotemporal clusters. Our autologistic regression analysis results showed that monthly average rainfall (OR = 2.187), monthly average temperature (OR = 4.329) and monthly relative humidity(OR = 2.070) were risk factors for HFMD spatiotemporal clusters, which were in agreement with some HFMD incidence reports [12, 44]. Warm weather, abundant rainfall and high humidity may facilitated the reproduction and transmission of enteroviruses, and facilitated the HFMD clusters. We also found that wind speed (OR = 0.258) has negative correlation with HFMD spatiotemporal clusters, and this compares well with observations by Gui et al. [42]. Wind speed may reduce the concentration of viruses per unit volume and could prevent HFMD virus spread through air and direct contact.

Our research showed that autologistic regression model has a higher goodness of fit than the ordinary one. The value of the constant is the prediction residual error of the regression model. The smaller the value is, the better the interpretation function of the model. By introducing the covariates SAuto cov i and TAuto cov i, the constant decreased significantly whilst the p-value of two covariates were less than 0.001,which indicated the existence of spatial and temporal autocorrelation. Thus, autologistic regression model could reduce the inherent residuals and bias of the model and improve the accuracy in evaluating the effect of determinants in spatio-temporal clustering of HFMD.

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, the quality of case reports in the surveillance system might vary from area to area due to differences in the availability of medical resources [4]. Some mild cases not going to hospitals also resulted in the underreporting of HFMD cases. Secondly, we chose the county as the least spatial unit which might lose some detailed information. It would have been a good idea to use a more finer areal unit scale such as village or community.

Conclusions

In summary, this study highlighted that the HFMD incidence from 2009 to 2015 in Hunan Province exhibited dynamic spatiotemporal distribution at county level, with the new shifting trend of clustering areas toward south and west. The autologistic regression model has a higher goodness of fit. After controlling for spatial-temporal heterogeneity, some meteorological parameters, especially rainfall, temperature and humidity might be associated with these clusters. Nevertheless, wind speed was the potential protect factors for the spatiotemporal patterns’ change of HFMD. Our findings provide information for a better understanding of epidemic trends and subsequently the development of more effective HFMD prevention and control strategies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Hunan Center for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the data of the notified hand, foot and mouth disease cases in Hunan Province. We acknowledged the efforts of local CDCs and hospitals in investigating and reporting these cases. We also would like to thank colleagues in the Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University for suggestions and software supports.

Funding

This work was supported by the program of Chinese Preventive Medicine Association Scientific Research Projects (20101801).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author’s contributions

XW and HT conceived the study, performed data analysis, interpretation and wrote the manuscript. SH sourced for funding. ABK contributed to the manuscript. QL and KL were responsible for data collection. YZ assisted in data access. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Abbreviations

- CoxA10

Coxsackievirus A10

- CoxA16

Coxsackievirus A16

- CoxA6

Coxsackievirus A6

- ECHO30

Enteric Cytopathic Human Orphan Virus 30

- EV71

Enterovirus 71

Additional file

Supplementary Table S1–S4. (DOCX 32 kb)

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hunan Center for Disease Prevention and Control. All data (including name, identity information, address, telephone number, etc.) were anonymized, and no individual information can be identified.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-017-2742-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xinrui Wu, Email: wuxinrui9@qq.com.

Shixiong Hu, Email: huql102@qq.com.

Abuaku Benjamin Kwaku, Email: babuaku@hotmail.com.

Qi Li, Email: 461028561@qq.com.

Kaiwei Luo, Email: 87616498@qq.com.

Ying Zhou, Email: yuanzhou1990@csu.edu.cn.

Hongzhuan Tan, Email: tanhz99@qq.com.

References

- 1.Hosoya M, Kawasaki Y, Sato M, Honzumi K, Kato A, Hiroshima T, Ishiko H, Suzuki H. Genetic diversity of enterovirus 71 associated with hand, foot and mouth disease epidemics in Japan from 1983 to 2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(8):691–694. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000227959.89339.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng KF, Chen LL, Huang PN, Shih SR. Neural pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 infection. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2010;12(7):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng T, Huang Y, Yu S, Gu J, Huang C, Xiao G, Hao Y. Spatial-temporal clusters and risk factors of hand, foot, and mouth disease at the district level in Guangdong Province. ChinaPloS one. 2013;8(2):e56943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hu M, Li Z, Wang J, Jia L, Liao Y, Lai S, Guo Y, Zhao D, Yang W. Determinants of the incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease in China using geographically weighted regression models. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chumakov M, Voroshilova M, Shindarov L, Lavrova I, Gracheva L, Koroleva G, Vasilenko S, Brodvarova I, Nikolova M, Gyurova S, et al. Enterovirus 71 isolated from cases of epidemic poliomyelitis-like disease in Bulgaria. Arch Virol. 1979;60(3–4):329–340. doi: 10.1007/BF01317504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishimaru Y, Nakano S, Yamaoka K, Takami S. Outbreaks of hand, foot, and mouth disease by enterovirus 71. High incidence of complication disorders of central nervous system. Arch Dis Child. 1980;55(8):583–588. doi: 10.1136/adc.55.8.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMinn P, Stratov I, Nagarajan L, Davis S. Neurological manifestations of enterovirus 71 infection in children during an outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Western Australia. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;32(2):236–242. doi: 10.1086/318454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen NT, Pham HV, Hoang CQ, Nguyen TM, Nguyen LT, Phan HC, Phan LT, Vu LN, Tran Minh NN. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of children who died from hand, foot and mouth disease in Vietnam, 2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Yang W, Ren J, Tan X, Wang Y, Mao N, Xu S, Zhu S, Cui A, et al. An emerging recombinant human enterovirus 71 responsible for the 2008 outbreak of hand foot and mouth disease in Fuyang city of China. Virol J. 2010;7:94. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing W, Liao Q, Viboud C, Zhang J, Sun J, Wu JT, Chang Z, Liu F, Fang VJ, Zheng Y, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China, 2008-12: an epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):308–318. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70342-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Deng T, Yu S, Gu J, Huang C, Xiao G, Hao Y. Effect of meteorological variables on the incidence of hand, foot, and mouth disease in children: a time-series analysis in Guangzhou. China BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li T, Yang Z, Di B, Wang M. Hand-foot-and-mouth disease and weather factors in Guangzhou, southern China. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(8):1741–1750. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang JX, Wang JF, Li ZJ, Wang Y, Lai SJ, Yang WZ. Visualized exploratory spatiotemporal analysis of hand-foot-mouth disease in southern China. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samphutthanon R, Tripathi NK, Ninsawat S, Duboz R. Spatio-temporal distribution and hotspots of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) in northern Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;11(1):312–336. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110100312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Cao Z, Zeng DD, Wang Q, Wang X, Qian H. Epidemiological analysis, detection, and comparison of space-time patterns of Beijing hand-foot-mouth disease (2008-2012) PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolan C, O'Halloran A, Bradley DG, Croke DT, Evans A, O'Brien JK, Dicker P, Shields DC. Genetic stratification of pathogen-response-related and other variants within a homogeneous Caucasian Irish population. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2005;13(7):798–806. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flahaut B, Mouchart M, San Martin E, Thomas I. The local spatial autocorrelation and the kernel method for identifying black zones. A comparative approach. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35(6):991–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattsson BJ, Zipkin EF, Gardner B, Blank PJ, Sauer JR, Royle JA. Explaining local-scale species distributions: relative contributions of spatial autocorrelation and landscape heterogeneity for an avian assemblage. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viladomat J, Mazumder R, McInturff A, McCauley DJ, Hastie T. Assessing the significance of global and local correlations under spatial autocorrelation: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 2014;70(2):409–418. doi: 10.1111/biom.12139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldhor T. The spatial autocorrelation coefficient Moran's I under heteroscedasticity. Stat Med. 1996;15(7–9):887–892. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960415)15:7/9<887::AID-SIM257>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.How Spatial Autocorrelation: Moran's I (Spatial Statistics) Works [http://edndoc.esri.com/arcobjects/9.2/net/shared/geoprocessing/spatial_statistics_tools/how_spatial_autocorrelation_colon_moran_s_i_spatial_statistics_works.htm].

- 22.Anselin L. Local indicators of spatial association-LISA. Geogr Anal. 1995;27:93–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu H, Zhang W, Xu H, Li P, Wu L, Guo P, Hao Y, Lu J, Zhang D: [predicating risk area of human infection with avian influenza a (H7N9) virus by using early warning model in China]. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi =Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi 2015, 36(5):470–475. [PubMed]

- 24.Kulldorff M, Huang L, Pickle L, Duczmal L. An elliptic spatial scan statistic. Stat Med. 2006;25(22):3929–3943. doi: 10.1002/sim.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulldorff M, Feuer EJ, Miller BA, Freedman LS. Breast cancer clusters in the northeast United States: a geographic analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(2):161–170. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinman KP, Abrams AM, Kulldorff M, Platt R. A model-adjusted space-time scan statistic with an application to syndromic surveillance. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(3):409–419. doi: 10.1017/S0950268804003528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulldorff M, Heffernan R, Hartman J, Assuncao R, Mostashari F. A space-time permutation scan statistic for disease outbreak detection. PLoS Med. 2005;2(3):e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anselin LS. I; Kho, Y: GeoDa: A introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr Anal. 2006;38:5–22. doi: 10.1111/j.0016-7363.2005.00671.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Besag J. Spatial interaction and the statistical analysis of lattice systems. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1974;36(2):192–236. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Feng Z, Yang Y, Self S, Gao Y, Longini IM, Wakefield J, Zhang J, Wang L, Chen X, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China: patterns of spread and transmissibility. Epidemiology. 2011;22(6):781–792. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318231d67a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bo YC, Song C, Wang JF, Li XW. Using an autologistic regression model to identify spatial risk factors and spatial risk patterns of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) in mainland China. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:358. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuang ZC, Kou ZQ, Bai YJ, Cong X, Wang LH, Li C, Zhao L, Yu XJ, Wang ZY, Wen HL. Epidemiological research on hand, foot, and mouth disease in mainland China. Viruses. 2015;7(12):6400–6411. doi: 10.3390/v7122947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Wang X, Liu Y, Sun D, Ding S, Zhang B, Du Z, Xue F. Detecting spatial-temporal clusters of HFMD from 2007 to 2011 in Shandong Province. China. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e63447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma E, Chan KC, Cheng P, Wong C, Chuang SK. The enterovirus 71 epidemic in 2008--public health implications for Hong Kong. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(9):e775–e780. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.02.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu W, Wu S, Xiong Y, Li T, Wen Z, Yan M, Qin K, Liu Y, Wu J. Co-circulation and genomic recombination of coxsackievirus A16 and enterovirus 71 during a large outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Central China. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian H, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Zhu S, Li X, Pan Z, Xu W, Xu B. Prevalence of multiple enteroviruses associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease in Shijiazhuang City, Hebei province, China: outbreaks of coxsackieviruses a10 and b3. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, Paananen A, Simonen ML, Vuorinen T, Roivainen M. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2010;48(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li JL, Yuan J, Yang F, Wu ZQ, Hu YF, Xue Y, Zhou BP, Jin Q. Epidemic characteristics of hand, foot, and mouth disease in southern China, 2013: coxsackievirus A6 has emerged as the predominant causative agent. The Journal of infection. 2014;69(3):299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mirand A, Henquell C, Archimbaud C, Ughetto S, Antona D, Bailly JL, Peigue-Lafeuille H. Outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease/herpangina associated with coxsackievirus A6 and A10 infections in 2010, France: a large citywide, prospective observational study. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2012;18(5):E110–E118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ang LW, Koh BK, Chan KP, Chua LT, James L, Goh KT. Epidemiology and control of hand, foot and mouth disease in Singapore. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 2009. 2001;38(2):106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu CH, Lu CY, Shao PL, Lee PI, Kao CL, Chung MY, Chang LY, Huang LM. Epidemiologic and clinical features of non-polio enteroviral infections in northern Taiwan in. Journal of microbiology, immunology, and infection = Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi 2011. 2008;44(4):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gui J, Liu Z, Zhang T, Hua Q, Jiang Z, Chen B, Gu H, Lv H, Dong C. Epidemiological characteristics and spatial-temporal clusters of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Zhejiang Province, China, 2008-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0139109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao J, Qin Z, Zuo Z, Yu S, Zhang J. Spatial-temporal mapping of hand foot and mouth disease and the long-term effects associated with climate and socio-economic variables in Sichuan Province, China from 2009 to 2013. Sci Total Environ. 2016;563-564:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu W, Ji H, Shan J, Bao J, Sun Y, Li J, Bao C, Tang F, Yang K, Bergquist R, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of hand-foot-mouth disease and its relationship with meteorological factors in Jiangsu Province. China. PloS one. 2015;10(6):e0131311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.