Abstract

Preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP syndrome are life-threatening hypertensive conditions and common causes of ICU admission among obstetric patients The diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia include: 1) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg on two occasions at least 4 hours apart and 2) proteinuria ≥300 mg/day in a woman with a gestational age of >20 weeks with previously normal blood pressures. Eclampsia is defined as a convulsive episode or altered level of consciousness occurring in the setting of preeclampsia, provided that there is no other cause of seizures. HELLP syndrome is a life-threatening condition frequently associated with severe preeclampsia-eclampsia and is characterized by three hallmark features of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets. Early diagnosis and management of preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP syndrome are critical with involvement of a multidisciplinary team that includes Obstetrics, Maternal Fetal Medicine and Critical Care. Expectant management may be acceptable before 34 weeks with close fetal and maternal surveillance and administration of corticosteroid therapy, parenteral magnesium sulfate and antihypertensive management. Worsening condition requires delivery. Complications that can be related to this spectrum of disease include disseminated Intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome, stroke, acute renal failure, hepatic dysfunction with hepatic rupture or liver hematoma and infection/sepsis.

Keywords: Complications, eclampsia, HELLP, Intensive Care Unit, management

INTRODUCTION

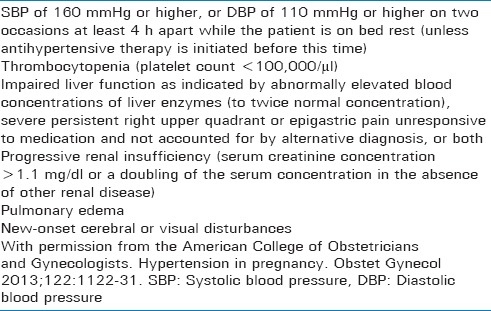

Preeclampsia, eclampsia, and Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzyme Levels and Low Platelet Levels (HELLP) syndrome are life-threatening hypertensive conditions that occur in pregnant woman. Preeclampsia is a multisystem disorder which complicates 3%–8% of all pregnancies.[1] The diagnostic criteria of preeclampsia include (1) systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg on two occasions at least 4 h apart and (2) proteinuria ≥300 mg/day in a woman with a gestational age of >20 weeks with previously normal blood pressures.[2] Severe hypertension or signs/symptoms of end-organ injury are considered to be the severe spectrum of the disease [Table 1]. Eclampsia is defined as a convulsive episode or altered level of consciousness occurring in the setting of preeclampsia, provided that there is no other cause of seizures.[2] HELLP syndrome is a life-threatening condition frequently associated with severe preeclampsia-eclampsia and is characterized by three hallmark features of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets.[3] Some researchers classify HELLP syndrome as part of microangiopathic hemolytic anemias including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the hemolytic uremic syndrome.[4] HELLP syndrome occurs in about 0.5%–0.9% of all pregnancies and in 10%–20% of pregnancies complicated by severe preeclampsia.[5]

Table 1.

Severe features of preeclampsia (any of these findings)

Pregnancy-induced hypertensive complications (preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome) contribute to a significant public health threat worldwide. Preeclampsia is one of the top six causes of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in the United States.[6] Globally, preeclampsia causes 70,000 maternal deaths and 50,000 infant deaths annually.[7] Similarly, eclampsia is responsible for another 50,000 maternal deaths annually worldwide.[8] HELLP syndrome is associated with a maternal mortality of 3.5%–24.2% and a perinatal mortality of 7.7%–60%.[9] The maternal mortality associated with HELLP syndrome is mainly due to renal failure, coagulopathy (i.e., disseminated intravascular coagulation [DIC]), pulmonary and cerebral edema, abruptio placentae, hepatic hemorrhage, and hypovolemic shock.[10] It may present antepartum in 69% of cases with the remaining 31% of cases occurring postpartum. Most of the postpartum cases occur within 48 h of delivery.[11]

MANAGEMENT OF ECLAMPSIA AND HELLP SYNDROME

Early diagnosis and management of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome are critical with the involvement of a multidisciplinary team that includes Obstetrics, Maternal Fetal Medicine, and Critical Care. Nonspecific presentations of these diseases (e.g., epigastric pain, malaise, nausea, vomiting, headache, and flu-like symptoms) can lead to delayed diagnosis. However, early detection and management of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome is key as it helps to prevent severe complications. Although the treatment for preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome is similar, these two conditions should be regarded as separate entities as changes in renin–angiotensin system, hypertension, and proteinuria may be absent in HELLP syndrome. Moreover, risk factors for the two conditions are different as HELLP syndrome tends to affect older, caucasian and multiparous women as compared with preeclampsia.[12]

Severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome are common causes of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission among obstetric patients. Because these conditions are life threatening and have high maternal and infant mortality rates, ICU care is recommended when two or more organ systems are failing and there is need for ventilator support.[13] The purpose of this paper is to discuss the issues encountered in the ICU in terms of management of eclampsia and HELLP syndrome and their complications such as coagulopathy and hemorrhage, cardiovascular (CV) instability, acute renal failure (ARF), infections, hepatic dysfunction, and need for mechanical ventilation. After establishing the diagnosis, optimal management of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome includes close monitoring for signs of obstetric complications, seizure management, blood pressure control, and delivery at an optimal time for the well-being of both the mother and baby.[14]

Close monitoring and expectant management

Although controversial, expectant management may be acceptable before 34 weeks in a tertiary care hospital. This should include close maternal and fetal surveillance (maternal vital signs and fluid balance, cardiotocography, and Doppler examination for fetal assessment) as well as serial laboratory assessments (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, coagulation profile, and lactate dehydrogenase).[15] In addition, corticosteroid (CS) therapy, parenteral magnesium sulfate therapy (for up to 48 h),[12] and antihypertensive management are recommended for pregnancies between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation.[16] However, conservative management must be weighed against the risk of maternal and fetal complications. Delivery is inevitable if the maternal or fetal condition worsens with the majority of these cases requiring cesarean section.[17]

Corticosteroid therapy

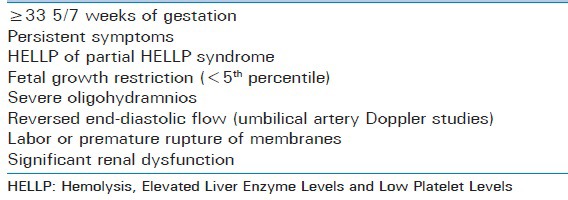

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy recommends antenatal CS therapy to accelerate fetal lung maturity for the affected pregnant woman with severe preeclampsia between 24 and 34 weeks of gestation. Delivery is indicated after 48 h of CS therapy in specific cases shown in Table 2. On the other hand, delivery is recommended immediately after maternal stabilization without delay for CS in cases of eclampsia, pulmonary edema, DIC, uncontrollable severe hypertension, abnormal fetal testing, nonviable fetus, intrauterine fetal demise, or placental abruption.[16,18]

Table 2.

Conditions requiring delivery after administration of corticosteroid

Delivery

Delivery is the only cure for preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome.[19] Indications, timing, and method of delivery largely depend on clinical acumen. If eclampsia or HELLP syndrome develops before 24 weeks of gestation, termination of pregnancy should be considered.[20] Cesarean delivery should be considered in the patients with HELLP syndrome and eclampsia <32–34 weeks of gestation where long induction with cervical ripening agents is expected. Most often, fetal bradycardia occurs during and immediately after a seizure. However, the fetal heart rate pattern improves with therapeutic interventions in the mother and fetus. In these cases, surgery can be delayed for a short period of time to allow for in utero resuscitation before delivery.[21,22]

Parenteral magnesium sulfate therapy

The patients with severe preeclampsia and suspected HELLP syndrome should receive parenteral magnesium sulfate therapy as prophylaxis for convulsions.[3,23] The magnesium sulfate regimen includes a loading dose of 6 g intravenous (IV) over 20 min followed by a continuous infusion of 2 grams/hr starting during the period of observation and continuing until 24-h postpartum.[3] If recurrent seizures occur, an additional bolus of 2 g magnesium sulfate can be given over 3–5 min. Close monitoring for magnesium toxicity is a necessity. If seizures are not controlled after two such boluses of magnesium sulfate, other anti-seizure drugs (e.g., diazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam) can be tried.[24] The ACOG Task Force also recommends magnesium sulfate therapy in the setting of eclampsia to prevent recurrent seizures rather than for control of the initial seizure since the initial seizure is usually self-limited.[16]

Antihypertensive management

ACOG Task Force recommends antihypertensive therapy for severe preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome if the blood pressure is ≥160/110 mmHg.[16] Severe elevations in blood pressure can cause cerebrovascular injury in the form of hypertensive encephalopathy with a massive increase in intracranial pressure and resultant cerebral edema or intracranial hemorrhage. To avoid this, antihypertensive medications (IV bolus doses of 5–10 mg of hydralazine given over 2 min or IV bolus doses of 20–80 mg of labetalol over 2 min or oral doses of 10–20 mg of nifedipine) are used to maintain BP in a safe range (140-150/90-100) without compromising cerebral perfusion and uteroplacental flow.[25] Second-line alternatives include labetalol or nicardipine drips. Sodium nitroprussiate should be reserved only for extreme emergencies due to its potential cyanide and thiocyanate toxicity as well as the risk of increased intracranial pressure.[25]

Platelet transfusion

Platelet transfusion is suggested for the patients with Class I HELLP syndrome (severe thrombocytopenia or platelets <50,000/μL) before cesarean section or when platelets are ≤20,000–25,000/μL before vaginal delivery.[26] Moreover, actively bleeding patients with thrombocytopenia and all those with platelet count <20,000/μL should receive a platelet transfusion to prevent excessive bleeding during delivery.[4] However, repeated platelet transfusions are not required due to the short half-life of platelets. This recommendation has been challenged by others. Vigil-De Gracia reports that the addition of platelet transfusion to CS therapy to increase platelet count does not improve the maternal outcomes in HELLP syndrome (i.e., resolution of HELLP syndrome which is recognized as normalization of the platelet count and length of hospital stay indicating stabilization of the disease).[27]

Management of complications

HELLP syndrome often accompanies preeclampsia and/or eclampsia, increasing the maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It may lead to multisystem organ failure. Listed below are some important complications of the spectrum of diseases.

Coagulopathy and hemorrhage/disseminated intravascular coagulation

Coagulopathy, hemorrhage, and DIC are serious complications of preeclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome. DIC has been reported in 15%–38% of the patients with HELLP syndrome.[28] DIC in preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome requires urgent cesarean delivery and multimodal management to halt the disease progression.[29] Prompt hemostatic management (i.e., massive transfusion of blood products and manual or pharmacologic contraction of the uterus) and clinical and laboratory surveillance by a multidisciplinary team may lead to spontaneous recovery in the 24–48 h following delivery. We recommend starting transfusions with clinical suspicion of coagulopathy even if laboratories are not readily available. Patients who do not respond to massive transfusions may benefit from recombinant factor VIIa[4] although this remains controversial.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a serious complication that affects <1% of the patients with HELLP syndrome.[3] It may prompt the need for mechanical ventilation. It has been reported that antepartum and postpartum mortality rates of ARDS are 23% and 50%, respectively.[30] One thing that must be born in mind in this setting is that such patients usually have laryngeal edema which may complicate intubation and lead to death. For this reason, surgical help should be on hand to provide an emergency surgical airway if needed.

Cardiovascular instability and stroke

Although some studies have found an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and nonhemorrhagic stroke in patients with this spectrum of disease, clinical and neuroimaging studies show cerebral edema resulting from vasomotor disturbances as the major cause of neurological deficits in these patients. The exact incidence of stroke in the acute setting is difficult to determine due to limited data from small retrospective studies or diagnosis at the time of autopsy which may not be representative of surviving patients. While some studies have failed to show an association of HELLP with cerebral hemorrhage, others have shown an incidence of up to 40%.[15]

Preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome are also associated with long-term adverse CV outcomes. Preeclampsia increases the CV risk in women by 2–4 times which is comparable to the CV risk associated with smoking.[31] Studies have reported that hypertensive complications of pregnancy are linked to chronic hypertension, premature myocardial infarction, and CV accidents.[32] However, this CV risk link needs to be further researched and evaluated. In this regard, follow-up to screen for CV outcomes and lifestyle modification (e.g., exercise, diet, and weight loss) should be considered in the patients with history of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and/or HELLP syndrome.

Acute renal failure

ARF is encountered in 1%–2% and 7.4% of the patients with preeclampsia-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome, respectively.[33,34] Other studies have reported ARF in up to 40% of the cases of severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome.[35] ARF due to pregnancy-induced hypertensive complications increases the maternal mortality rate. Early management in such cases includes hemodynamic stabilization, fluid balance, electrolyte correction, and possibly dialysis along with close monitoring of the fetus.[36] Fluid management may be complicated by the vascular permeability and third spacing of fluids in those with active disease.

Infections/sepsis

Pregnancy itself predisposes the pregnant woman to certain infections (e.g., pyelonephritis, pneumonia, endometritis, and septic abortion).[10] Studies have reported that HELLP syndrome is associated with frequent infections particularly if cesarean section is performed.[15] The most common infection causing agents during pregnancy include group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus and Escherichia coli.[37] Therefore, adequate fluid resuscitation, empiric antibiotics, and preventive measures against infections must be considered.

Hepatic dysfunction/hepatic rupture/liver hematoma

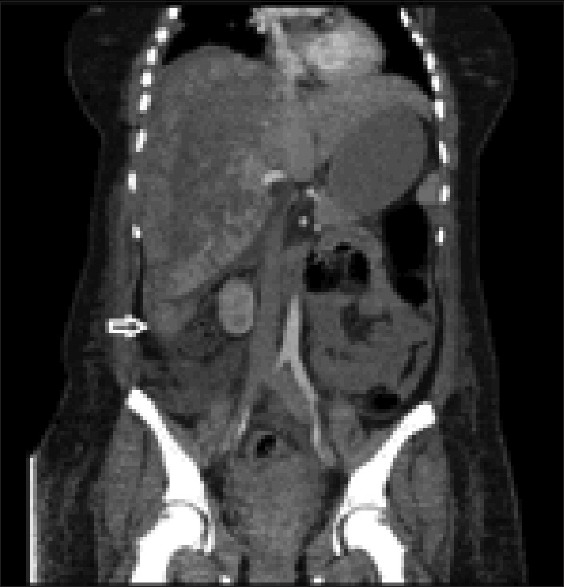

Hepatic failure and liver hemorrhage or hematoma are grave complications of HELLP syndrome.[38] Subcapsular hematoma affects 0.9%–1.6% of the patients suffering from HELLP syndrome.[3] It may be mistaken for pulmonary embolism or other intra-abdominal pathology. Rupture of a subcapsular hematoma may lead to a catastrophic outcome. Although the mainstay of treatment for a subcapsular hepatic hematoma is surgery, Ditisheim and Sibai have recently reported that conservative treatment may be successful in a large number of patients with unruptured subcapsular liver hematoma as shown in Figure 1 affects. Conservative management includes blood transfusion as needed, correction of coagulopathy, and serial imaging with ultrasound or computer tomography to monitor the size of the hematoma.[38]

Figure 1.

Abdominal computed tomography showing subcapsular liver hematoma

Ventilatory requirements

Mechanical ventilation is required in 30% of the patients with HELLP syndrome admitted in ICU.[39] The most common causes for intubation and mechanical ventilation were respiratory failure, hemodynamic instability, and a history of emergency cesarean section. The patients with HELLP syndrome requiring mechanical ventilation have a poor prognosis.[40]

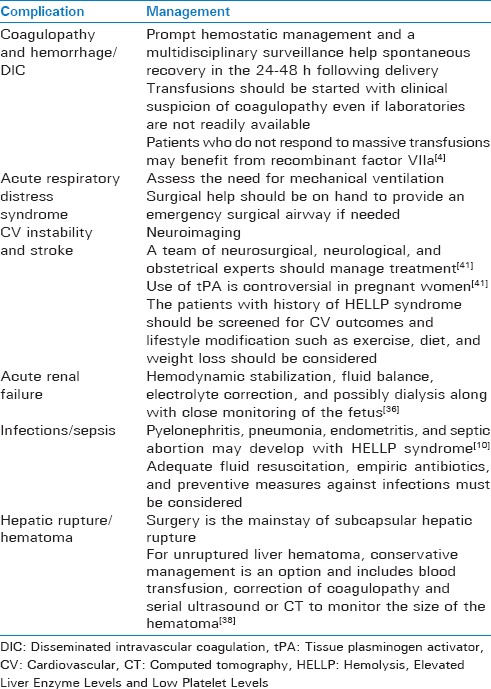

Table 3 summarizes all the above complications and their corresponding management recommendations.

Table 3.

Complications of HELLP syndrome and their management

CONCLUSION

Preeclampsia, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome are serious and life-threatening conditions encountered by pregnant woman. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment through a multidisciplinary team in an ICU setting can prevent complications and reduce morbidity and mortality. Expectant management for nonserious cases including CS therapy before 34-week gestation, anti-seizure therapy with magnesium sulfate, and antihypertensive therapy for >160/110 mmHg is appropriate. Platelet transfusions should be performed for platelet counts <20,000/μL. Delivery at 34-week gestation or for deteriorating maternal or fetal condition before 34-week gestation is recommended to improve the focused outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carty DM, Delles C, Dominiczak AF. Preeclampsia and future maternal health. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1349–55. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833a39d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzan J, Carbonnel M, Piconne O, Asmar R, Ayoubi JM. Pre-eclampsia: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:467–74. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S20181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sibai BM. Diagnosis, controversies, and management of the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:981–91. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000126245.35811.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haram K, Mortensen JH, Mastrolia SA, Erez O. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in the HELLP syndrome: How much do we really know? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:779–88. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1189897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karumanchi SA, Maynard SE, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP. Preeclampsia: A renal perspective. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2101–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih T, Peneva D, Xu X, Sutton A, Triche E, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. The rising burden of preeclampsia in the United States impacts both maternal and child health. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:329–38. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367:1066–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das R, Biswas S. Eclapmsia: The major cause of maternal mortality in Eastern India. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25:111–6. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v25i2.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sibai BM, Taslimi MM, el-Nazer A, Amon E, Mabie BC, Ryan GM, et al. Maternal-perinatal outcome associated with the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets in severe preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:501–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neligan PJ, Laffey JG. Clinical review: Special populations – Critical illness and pregnancy. Crit Care. 2011;15:227. doi: 10.1186/cc10256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sibai BM. The HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets): Much ado about nothing? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:311–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90376-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnik R, Creasy R, Jams J, Lockwood C, Moore T. Creasy and Resnik's Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trikha A, Singh P. The critically ill obstetric patient – Recent concepts. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:421–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.71041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsley DM. Hematologic complications of pregnancy. Semin Hematol. 2013;50:222–31. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haram K, Svendsen E, Abildgaard U. The HELLP syndrome: Clinical issues and management. A review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American college of obstetricians and gynecologists’ task force on hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddad B, Sibai BM. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia: Proper candidates and pregnancy outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48:430–40. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000160315.67359.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gul A, Cebeci A, Aslan H, Polat I, Ozdemir A, Ceylan Y, et al. Perinatal outcomes in severe preeclampsia-eclampsia with and without HELLP syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2005;59:113–8. doi: 10.1159/000082648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debette M, Samuel D, Ichai P, Sebagh M, Saliba F, Bismuth H, et al. Labor complications of the HELLP syndrome without any predictive factors. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:264–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole JH. Aggressive management of HELLP syndrome and eclampsia. AACN Clin Issues. 1997;8:524–38. doi: 10.1097/00044067-199711000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nassar AH, Adra AM, Chakhtoura N, Gómez-Marín O, Beydoun S. Severe preeclampsia remote from term: Labor induction or elective cesarean delivery? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1210–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul RH, Koh KS, Bernstein SG. Changes in fetal heart rate-uterine contraction patterns associated with eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;130:165–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(78)90361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin JN., Jr Milestones in the quest for best management of patients with HELLP syndrome (microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, hepatic dysfunction, thrombocytopenia) Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delgado-Escueta AV, Wasterlain C, Treiman DM, Porter RJ. Current concepts in neurology: Management of status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:1337–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198206033062205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period. ACOG committee opinion number 692. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e90–e95. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baxter JK, Weinstein L. HELLP syndrome: The state of the art. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:838–45. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000146948.19308.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigil-De Gracia P. Addition of platelet transfusions to corticosteroids does not increase the recovery of severe HELLP syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;128:194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg R, Nath MP, Bhalla AP, Kumar A. Disseminated intravascular coagulation complicating HELLP syndrome: Perioperative management. BMJ Case Reports. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.10.2008.1027. 2009: bcr10.2008.1027 Doi:10.1136/bcr.10.2008.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Dam PA, Renier M, Baekelandt M, Buytaert P, Uyttenbroeck F. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets in severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Catanzarite VA, Willms D. Adult respiratory distress syndrome in pregnancy: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997;52:381–92. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen CW, Jaffe IZ, Karumanchi SA. Pre-eclampsia and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;101:579–86. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lykke JA, Langhoff-Roos J, Sibai BM, Funai EF, Triche EW, Paidas MJ, et al. Hypertensive pregnancy disorders and subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the mother. Hypertension. 2009;53:944–51. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sibai BM, Ramadan MK. Acute renal failure in pregnancies complicated by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1682–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90678-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibai BM, Villar MA, Mabie BC. Acute renal failure in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy outcome and remote prognosis in thirty-one consecutive cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:777–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1299–306. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a45b25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alsuwaida AO. Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of acute kidney injury during pregnancy. Nephrol Urol Mon. 2011;4:340–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, Garrod D, et al. Saving mothers' lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The eighth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ditisheim A, Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of HELLP syndrome complicated by liver hematoma. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017;60:190–7. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osmanagaoglu MA, Osmanagaoglu S, Ulusoy H, Bozkaya H. Maternal outcome in HELLP syndrome requiring Intensive Care management in a Turkish hospital. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124:85–9. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802006000200007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gedik E, Yucel N, Sahin T, Koca E, Colak YZ, Togal T. Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet syndrome: Outcomes for patients admitted to Intensive Care at a tertiary referral hospital. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2017;36:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10641955.2016.1218505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosley CM, McCullough LD. Acute neurological issues in pregnancy and the peripartum. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1:104–16. doi: 10.1177/1941875211399126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]