Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Medical students are at high risk for depression and suicidal ideation. However, the prevalence estimates of these disorders vary between studies.

OBJECTIVE

To estimate the prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in medical students.

DATA SOURCES AND STUDY SELECTION

Systematic search of EMBASE, ERIC, MEDLINE, psycARTICLES, and psycINFO without language restriction for studies on the prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, or suicidal ideation in medical students published before September 17, 2016. Studies that were published in the peer-reviewed literature and used validated assessment methods were included.

DATA EXTRACTION AND SYNTHESIS

Information on study characteristics; prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation; and whether students who screened positive for depression sought treatment was extracted independently by 3 investigators. Estimates were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis. Differences by study-level characteristics were estimated using stratified meta-analysis and meta-regression.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Point or period prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, or suicidal ideation as assessed by validated questionnaire or structured interview.

RESULTS

Depression or depressive symptom prevalence data were extracted from 167 cross-sectional studies (n = 116 628) and 16 longitudinal studies (n = 5728) from 43 countries. All but 1 study used self-report instruments. The overall pooled crude prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms was 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals; 95% CI, 24.7% to 29.9%, I2 = 98.9%). Summary prevalence estimates ranged across assessment modalities from 9.3% to 55.9%. Depressive symptom prevalence remained relatively constant over the period studied (baseline survey year range of 1982–2015; slope, 0.2% increase per year [95% CI, −0.2% to 0.7%]). In the 9 longitudinal studies that assessed depressive symptoms before and during medical school (n = 2432), the median absolute increase in symptoms was 13.5% (range, 0.6% to 35.3%). Prevalence estimates did not significantly differ between studies of only preclinical students and studies of only clinical students (23.7% [95% CI, 19.5% to 28.5%] vs 22.4% [95% CI, 17.6% to 28.2%]; P = .72). The percentage of medical students screening positive for depression who sought psychiatric treatment was 15.7% (110/954 individuals; 95% CI, 10.2% to 23.4%, I2 = 70.1%). Suicidal ideation prevalence data were extracted from 24 cross-sectional studies (n = 21 002) from 15 countries. All but 1 study used self-report instruments. The overall pooled crude prevalence of suicidal ideation was 11.1% (2043/21 002 individuals; 95% CI, 9.0% to 13.7%, I2 = 95.8%). Summary prevalence estimates ranged across assessment modalities from 7.4% to 24.2%.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

In this systematic review, the summary estimate of the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical students was 27.2% and that of suicidal ideation was 11.1%. Further research is needed to identify strategies for preventing and treating these disorders in this population.

Studies have suggested that medical students experience high rates of depression and suicidal ideation.1 However, estimates of the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among students vary across studies from 1.4% to 73.5%,2,3 and those of suicidal ideation vary from 4.9% to 35.6%.4,5 Studies also report conflicting findings about whether student depression and suicidality vary by undergraduate year, sex, or other characteristics.6–11

Reliable estimates of depression and suicidal ideation prevalence during medical training are important for informing efforts to prevent, treat, and identify causes of emotional distress among medical students,12 especially in light of recent work revealing a high prevalence of depression in resident physicians.13 We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in undergraduate medical trainees.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Eligibility

Two authors (M.A.R. and D.A.M.) independently identified cross-sectional and longitudinal studies published prior to September 17, 2016, that reported on the prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, or suicidal ideation in medical students by systematically searching EMBASE, ERIC, MEDLINE, psycARTICLES, and psycINFO. In addition, the authors screened the reference lists of identified articles and corresponded with study investigators using the approaches implied by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines.14,15

For the database searches, terms related to medical students and study design were combined with those related to depression and suicide without language restriction (complete details of the search strategy appear in eMethods 1 in the Supplement). Included studies (1) reported data on medical students, (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals, and (3) used a validated method to assess for depression, depressive symptoms, or suicidal ideation.16 A third author (L.S.R.) resolved discrepancies by discussion and adjudication.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Three authors (L.S.R., M.T., and J.B.S.) independently extracted the following data from each article using a standardized form: study design; geographic location; years of survey; year in school; sample size; average age of participants; number and percentage of male participants; diagnostic or screening method used; outcome definition (ie, specific diagnostic criteria or screening instrument cutoff); and reported prevalence estimates of depression, depressive symptoms, or suicidal ideation. Whether students who screened positive for depression sought psychiatric or other mental health treatment also was extracted. When there were studies involving the same population of students, only the most comprehensive or recent publication was included.

The same 3 authors independently assessed the risk of bias of these nonrandomized studies using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, which assesses sample representativeness and size, comparability between respondents and nonrespondents, ascertainment of depressive or suicidal symptoms, and thoroughness of descriptive statistics reporting (complete details regarding scoring appear in eMethods 2 in the Supplement).17 Studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (≥3 points) or high risk of bias (<3 points). A fourth author (D.A.M.) resolved discrepancies through discussion and adjudication.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Prevalence estimates of depression or depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation were calculated by pooling the study-specific estimates using random-effects meta-analyses that accounted for between-study heterogeneity.18 The same approach was used to estimate the summary percentage of students screening positive for depression who sought treatment. When studies reported point prevalence estimates made at different periods within the year, the overall period prevalence was used. Standard χ2 tests and the I2 statistic (ie, the percentage of variability in prevalence estimates due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error, or chance, with values ≥75% indicating considerable heterogeneity) were used to assess between-study heterogeneity.19,20

Sensitivity analyses were performed by serially excluding each study to determine the influence of individual studies on the overall prevalence estimates. Results from studies grouped according to prespecified study-level characteristics were compared using stratified meta-analysis (for diagnostic criteria or screening instrument cutoff, study design, undergraduate level, continent or region, country, and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale components) or random-effects meta-regression (for year of baseline survey, age, and sex).21,22 To isolate associations within the medical school experience from associations with assessment tools, an analysis restricted to longitudinal studies reporting both pre- and intramedical school depressive symptom prevalence estimates was performed.

Bias secondary to small study effects was investigated using funnel plots and the Egger test.23,24 All analyses were performed using R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).25 Statistical tests were 2-sided and used a significance threshold of P < .05.

Results

Study Characteristics

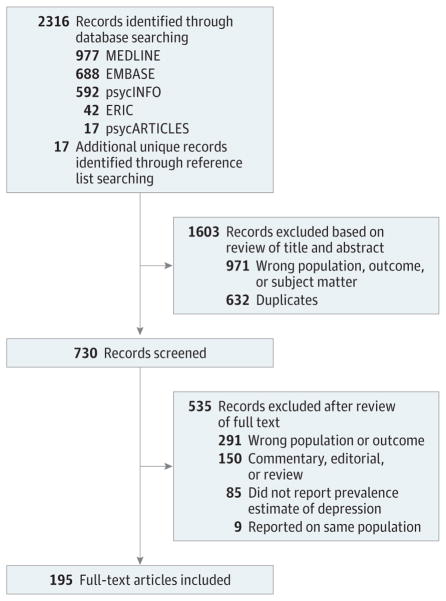

One hundred ninety-five studies2–11,26–210 involving a total of 129 123 individuals in 47 countries were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The median number of participants per study was 336 (range, 44–10 140). One hundred sixty-seven cross-sectional studies2–4,6–9,11,26–184 (n = 116 628) and 16 longitudinal studies10,196–210 (n = 5728) in 43 countries reported on depression or depressive symptom prevalence (Table 1). Twenty-four cross-sectional studies (n = 21 002) in 15 countries reported on the prevalence of suicidal ideation (Table 2).4,5,34,62,65,73,74,79,112,160,165,167,174,185–195

Figure 1.

Study Identification and Selection

Table 1.

Selected Characteristics of the 183 Studies of Depression or Depressive Symptomsa

| Source | Country | Survey Years | Year of Training | No. of Students | Age, y | Men, No. (%) | Instrument and Cutoff Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bore et al,52 2016 | Australia | 2013 | 1–5 | 127 | Mean (SD): 23 (5.6) | 32 (25.6) | DASS-21 ≥10 |

| De Sousa Lima et al,67 2010 | Brazil | 2001 | 1–4 | 80 | Range: 18–30 | 45 (56.3) | BDI ≥10 |

| de Melo Cavestro and Rocha,652006 | Brazil | 2003 | 1–6 | 213 | Mean (SD): 23.1 (2.3) | 109 (51.2) | MINI ≥ DSM IV criteria |

| Amaral et al,39 2008 | Brazil | 2006 | 1–6 | 287 | Mean: 21.3 | 131 (45.7) | BDI ≥10 |

| Costa et al,61 2012 | Brazil | 2008 | 5, 6 | 84 | NR | NR | BDI ≥10 |

| Serra et al,147 2015 | Brazil | 2012 | 1–6 | 657 | Mean: 22.7 | 255 (38.8) | BDI ≥10 |

| Castaldelli-Maia et al,55 2012 | Brazil | 2001–2006 | 1–6 | 465 | NR | NR | BDI ≥15 |

| Alexandrino-Silva et al,34 2009 | Brazil | 2006–2007 | 1–6 | 336 | Mean (SD): 22.4 (2.5) | 105 (31) | BDI ≥21 |

| Paro et al,130 2010 | Brazil | 2006–2007 | 1–6 | 352 | Mean (SD): 22.3 (2.4) | 134 (38.4) | BDI >9 |

| Bassols et al,49 2014 | Brazil | 2010–2011 | 1, 6 | 232 | Mean (SD): 23.1 (3.2) | 117 (50.4) | BDI ≥11 |

| Del-Ben et al,200 2013 | Brazil | NR | 1 | 85 | Mean (SD): 19.1 (1.6) | 58 (68.2) | BDI ≥10 |

| Leão et al,66 2011 | Brazil | NR | 6 | 111 | Mean (SD): 24.6 (1.4) | 87 (56) | BDI ≥12 |

| Hirata et al,87 2007 | Brazil | NR | 1–2 | 161 | Mean (SD): 22.1 (2.1) | 77 (47.8) | BDI >10 |

| Baldassin et al,47 2008 | Brazil | NR | 1–6 | 481 | Mean (SD): 21.9 (2.4) | 195 (40.5) | BDI ≥10 |

| Matheson et al,117 2016 | Canada | 2013 | 1–4 | 232 | NR | NR | K-10 ≥20 |

| Helmers et al,84 1997 | Canada | 1994–1995 | 1–4 | 356 | Mean (SD): 23.5 (2.6) | 185 (52) | DSP >50 |

| Berner et al,51 2014 | Chile | 2012 | 1–5 | 384 | Mean (SD): 20.8 (1.8) | 224 (58.3) | GHQ-12 ≥5 |

| Tang,163 2005 | China | 2003 | 2 | 121 | NR | 0 | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Shen et al,151 2009 | China | 2006 | 1 | 313 | Mean (SD): 23.8 (1.8) | NR | Zung-SDS ≥53 |

| Wan et al,4 2012 | China | 2010 | 1–5 | 4063 | Mean (SD): 20.5 (1.1) | 1895 (46.6) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Sobowale et al,160 2014 | China | 2012 | 2–3 | 348 | NR | NR | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Shi et al,154 2015 | China | 2014 | 1–5 | 1738 | Mean (SD): 21.4 (1.6) | 586 (33.7) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Shi et al,153 2016 | China | 2014 | 1–7 | 2925 | Mean (SD): 21.7 (2) | 1028 (35.2) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Pan et al,129 2016 | China | 2013–2014 | 1–5 | 8819 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (1.6) | 3415 (37.9) | BDI ≥14 |

| Liao et al,110 2010 | China | NR | 1 | 487 | Mean (SD): 18.5 (0.8) | 181 (37.4) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Sun et al,162 2011 | China | NR | 1–2 | 10140 | Mean (SD): 19.6 (1.3) | 4680 (46.2) | BDI ≥10 |

| Yang et al,6 2014 | China | NR | 1–5 | 1137 | Range: 17–24 | 624 (54.9) | SCL-90 >2 |

| Pinzón-Amado et al,137 2013 | Colombia | 2006 | 1–6 | 973 | Mean (SD): 20.3 (2.3) | 414 (43) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Amir and Gillany,40 2010 | Egypt | 2010 | 1–6 | 311 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (2.4) | 164 (52.7) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Ibrahim and Abdelreheem,89 2015 | Egypt | 2013 | 1 | 164 | NR | 82 (50) | BDI ≥17 |

| Abdel Wahed and Hassan,27 2016 | Egypt | 2015 | 1–4 | 442 | Mean (SD): 20.2 (1.9) | 172 (38.9) | DASS-21 ≥10 |

| Eller et al,184 2006 | Estonia | 2003 | 1–6 | 413 | Mean (SD): 21.3 (2.5) | 95 (23) | EST-Q ≥12 |

| Vaysse et al,171 2014 | France | 2012–2013 | 2 | 197 | Mean (SD): 19.7 (0.9) | 79 (39.9) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Prinz et al,2 2012 | Germany | 2008 | 4, 5 | 73 | NR | 54 (74) | HADS-D ≥11 |

| Voltmer et al,172 2012 | Germany | 2010–2011 | 1, 2, 5 | 153 | Mean (SD): 25.6 (3.1) | 44 (28.7) | HADS-D ≥11 |

| Kötter et al,107 2014 | Germany | 2011–2012 | 1 | 350 | Mean (SD): 20.9 (3.2) | 118 (33.7) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Wege et al,174 2016 | Germany | 2012–2013 | 1 | 590 | Mean (SD): 21.1 (3.9) | 177 (29.9) | PHQ-9 >10 |

| Jurkat et al,100 2011 | Germany | NR | 1, 4 | 651 | NR | 252 (38.7) | BDI ≥11 |

| Kohls et al,105 2012 | Germany | NR | NR | 419 | NR | 122 (29.1) | ADS-K >17 |

| Nasioudis et al,126 2015 | Greece | 2013 | 1–3 | 146 | Mean (SD): 19.8 (1) | 91 (62.3) | Zung-SDS >45 |

| Chan,57 1992 | Hong Kong | NR | 1 | 95 | Mean (range): 19.6 (18–29) | 64 (67.4) | BDI ≥19 |

| Chan,56 1991 | Hong Kong | NR | 1–4 | 335 | Mean (SD): 20.1 (1.6) | 239 (71.3) | BDI ≥10 |

| Kumar et al,26 2012 | India | 2008 | 1–4 | 400 | NR | 217 (54.3) | BDI ≥10 |

| Gupta and Basak,82 2013 | India | 2008 | 1–5 | 150 | Range: 18–26 | 104 (69.3) | BDI ≥10 |

| David and Hamid Hashmi,64 2013 | India | 2012 | 1 | 128 | Mean (range): 17.9 (17–21) | 46 (35.9) | BDI ≥17 |

| Vankar et al,170 2014 | India | 2012 | 1–4 | 331 | Mean (SD): 19.8 (1.4) | 178 (53.8) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Iqbal et al,95 2015 | India | 2012 | 1–5 | 353 | Mean (SD): 20.8 (1.5) | 145 (41.1) | DASS-42 ≥10 |

| Ali and Vankar,37 1994 | India | NR | 1–3 | 215 | Mean (range): 19.6 (17–25) | 132 (61.4) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Supe,3 1998 | India | NR | 1–3 | 238 | NR | 128 (53.8) | Zung-SDS ≥40 |

| Sidana et al,156 2012 | India | NR | 1–5 | 237 | NR | 126 (53.2) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Bayati et al,9 2009 | Iran | 2008 | NR | 172 | NR | NR | GHQ-28 ≥23 |

| Akbari et al,31 2014 | Iran | 2011 | NR | 138 | NR | NR | GHQ-28 >6 |

| Farahangiz et al,76 2016 | Iran | 2014 | 1–4 | 208 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (1.1) | 82 (39.4) | GHQ-28 ≥23 |

| Vahdat Shariatpanaahi et al,150 2007 | Iran | 2004–2005 | NR | 192 | Mean (SD): 24.5 (1.6) | 0 | BDI ≥10 |

| Aghakhani et al,29 2011 | Iran | NR | NR | 628 | Mean (SD): 22 (0.3) | 334 (53.2) | BDI ≥10 |

| Ashor,43 2012 | Iraq | 2010–2011 | 1–6 | 269 | NR | 147 (54.6) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Lupo and Strous,111 2011 | Israel | NR | 1–6 | 119 | Mean (SD): 25.1 (2.8) | NR | BDI-II ≥10 |

| Peleg-Sagy and Shahar,131 2012 | Israel | NR | 1–7 | 60 | Mean (SD): 27 (2.9) | 0 | CES-D ≥16 |

| Peleg-Sagy and Shahar,205 2013 | Israel | NR | 1, 4, 7 | 192 | Mean (SD): 26.6 (2.6) | 0 | CES-D ≥16 |

| Yoon et al,179 2014 | Korea | NR | 2, 3, 5 | 174 | Mean (SD): 23.3 (2.8) | 96 (55.2) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Naja et al,125 2016 | Lebanon | 2014 | 2–5 | 340 | NR | 145 (42.6) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Mehanna and Richa,119 2006 | Lebanon | 2003–2004 | 1–6 | 356 | NR | NR | BDI ≥8 |

| Bunevicius et al,53 2008 | Lithuania | 2005 | NR | 338 | Mean (SD): 21 (1) | 73 (21.6) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Mancevska et al,114 2008 | Macedonia | 2007–2008 | 1–2 | 354 | NR | 120 (33.9) | BDI ≥17 |

| Sherina et al,152 2004 | Malaysia | 2002 | 1–5 | 396 | Mean (range): 21.6 (18–29) | 152 (38.4) | GHQ-12 ≥4 |

| Tan et al,167 2015 | Malaysia | 2013 | 1–5 | 537 | NR | 188 (35) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Yusoff et al,46 2011 | Malaysia | 2008 | 5 | 92 | NR | 25 (27.2) | BDI ≥9 |

| Yusoff,181 2013 | Malaysia | 2009–2010 | 1 | 194 | NR | 66 (34) | DASS-21 ≥14 |

| Yusoff et al,210 2013 | Malaysia | 2010–2011 | 1 | 170 | NR | 57 (32.8) | DASS-21 ≥10 |

| Saravanan and Wilks,145 2014 | Malaysia | NR | 1–5 | 358 | NR | 177 (49.4) | DASS-21 ≥10 |

| Manaf et al,113 2016 | Malaysia | NR | 2–5 | 206 | Mean (SD): 19.5 (2.6) | 0 | PHQ-9 ≥5 |

| Guerrero López et al,7 2013 | Mexico | 2007 | 1 | 455 | Mean (SD): 18.3 (1.2) | 139 (30.5) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Romo-Nava et al,142 2016 | Mexico | 2011 | 1–5 | 1068 | NR | 421 (39.4) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Melo-Carrillo et al,120 2012 | Mexico | 2006–2007 | 1–4 | 302 | NR | NR | BDI ≥10 |

| Nava et al,127 2013 | Mexico | 2010–2011 | 1, 5 | 1871 | NR | 707 (37.9) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| El-Gilany et al,75 2008 | Multiple | 2007 | 1–6 | 588 | Mean: 20.8 | 588 (100) | HADS-D ≥12 |

| Seweryn et al,148 2015 | Multiple | 2015 | 1–6 | 1262 | Median: 22 | 345 (27.3) | BDI ≥10 |

| Sreeramareddy et al,161 2007 | Nepal | 2005–2006 | NR | 407 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (1.8) | 227 (55.8) | GHQ-12 ≥4 |

| Basnet et al,48 2012 | Nepal | 2008–2009 | 1, 3 | 94 | Mean (SD): 21.2 (1.7) | 57 (60.6) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Borst et al,197 2015 | Netherlands | 2010–2011 | 1–6 | 951 | Mean (SD): 23 (2.6) | 279 (29) | BSI-DEP >0.41 |

| Carter et al,54 2014 | New Zealand | 2010 | 4–6 | 198 | Mean (SD): 23.5 (2.1) | 75 (38.1) | DASS-21 ≥14 |

| Samaranayake and Fernando,144 2011 | New Zealand | 2008–2009 | 3 | 255 | Median (range): 20 (18–36) | 123 (48.2) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Oku et al,128 2015 | Nigeria | 2010 | 1, 2, 4, 5 | 451 | Mean (SD): 23.4 (4.4) | 288 (63.8) | GHQ-12 ≥4 |

| Aniebue and Onyema,42 2008 | Nigeria | 2008–2009 | NR | 262 | Mean (SD): 23.7 (2.7) | 133 (50.8) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Rab et al,138 2008 | Pakistan | 2002 | 1–5 | 87 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (1.9) | 0 | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Jadoon et al,97 2010 | Pakistan | 2008 | 1–5 | 482 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (1.8) | 257 (53.3) | AKUADS ≥19 |

| Marwat,116 2013 | Pakistan | 2011 | 3 | 166 | NR | 73 (28.7) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Imran et al,92 2016 | Pakistan | 2013 | NR | 527 | Mean (SD): 20.2 (2.3) | 282 (53.5) | GHQ-12 >15 |

| Khan et al,103 2015 | Pakistan | 2014 | 3 | 110 | Mean: 21 | 55 (50) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Ali et al,36 2015 | Pakistan | 2014 | 1–2 | 182 | NR | 114 (62.6) | AKUADS >19 |

| Rizvi et al,140 2015 | Pakistan | 2014 | 1–5 | 66 | Mean (SD): 22.2 (1.3) | 28 (40) | DASS-42 ≥10 |

| Alvi et al,38 2010 | Pakistan | 2007–2008 | 2–5 | 279 | Mean (SD): 21.4 (1.4) | 77 (27.6) | BDI-II ≥14 |

| Waqas et al,173 2015 | Pakistan | 2014–2015 | 1–5 | 409 | Mean (SD): 19.9 (1.3) | 123 (30) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Inam et al,93 2003 | Pakistan | NR | 1–4 | 189 | NR | 60 (31.7) | AKUADS ≥19 |

| Khan et al,11 2006 | Pakistan | NR | 1–5 | 142 | Mean (SD): 21.3 (1.9) | 59 (41.5) | AKUADS ≥19 |

| Perveen et al,133 2016 | Pakistan | NR | 1,5 | 1000 | NR | 431 (43.1) | QIDS ≥9 |

| Mojs et al,122 2015 | Pakistan | NR | NR | 477 | NR | NR | KADS ≥6 |

| Phillips et al,134 2006 | Panama | 2005 | 1–6 | 122 | NR | 63 (51.6) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Pereyra-Elías et al,132 2010 | Peru | 2010 | 1–4 | 590 | Mean (SD): 19 (2.5) | 184 (28.9) | Zung SF ≥22 |

| Valle et al,169 2013 | Peru | 2010 | 1–6 | 615 | Mean (SD): 22 (4.5) | 357 (58) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Walkiewicz et al,209 2012 | Poland | 1999–2005 | 2 | 178 | NR | NR (69) | MMPI-D >70 |

| Adamiak et al,28 2004 | Poland | NR | 2, 4 | 263 | Mean: 22.3 | NR | BDI ≥12 |

| Inam,94 2007 | Saudi Arabia | 2002 | 1–3 | 226 | NR | 149 (65.9) | AKUADS ≥19 |

| Aziz et al,45 2011 | Saudi Arabia | 2010 | 1–5 | 295 | Mean (SD): 21.6 (1.7) | 0 | BDI-II ≥20 |

| AlFaris et al,35 2014 | Saudi Arabia | 2011 | 1–2 | 543 | NR | 340 (62.6) | BDI-II ≥14 |

| Ibrahim et al,91 2013 | Saudi Arabia | 2012 | 2–6 | 558 | Mean (SD): 21.7 (1.8) | 300 (50.3) | HADS-D ≥11 |

| Ibrahim et al,90 2013 | Saudi Arabia | 2010–2011 | 2–6 | 450 | Mean (SD): 21.1 (1.4) | 0 | HADS-D ≥11 |

| Kulsoom and Afsar,108 2015 | Saudi Arabia | 2012–2013 | 1–5 | 442 | NR | 274 (62) | DASS-21 ≥14 |

| Al-Faris et al,8 2012 | Saudi Arabia | NR | 1–5 | 797 | Mean (SD): 21.6 (1.6) | 590 (74) | BDI ≥10 |

| Saeed et al,143 2016 | Saudi Arabia | NR | NR | 80 | Mean (SD): 25.9 (1.5) | 55 (68.8) | K-10 ≥20 |

| Ristić-Ignjatović et al,139 2013 | Serbia | 2002–2012 | 4 | 615 | Mean (SD): 23.6 (1.5) | 239 (36.8) | BDI ≥10 |

| Miletic et al,121 2015 | Serbia | 2012–2013 | 1, 3, 6 | 1294 | Mean (SD): 21.9 (2.8) | 500 (38.6) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Pillay et al,136 2016 | South Africa | NR | 1–5 | 230 | Mean: 21 | 66 (28.7) | Zung-SDS >30 |

| Jeong et al,99 2010 | South Korea | 2008 | 1–2 | 89 | NR | 0 | CES-D ≥16 |

| Kim and Roh,104 2014 | South Korea | 2011 | 1–2 | 122 | NR | 92 (75.4) | BDI ≥10 |

| Choi et al,60 2015 | South Korea | 2013 | 1–4 | 534 | NR | 308 (57.7) | BDI-II ≥17 |

| Roh et al,141 2009 | South Korea | 2006–2007 | 1–4 | 7357 | NR | NR | BDI ≥16 |

| Dahlin et al,63 2011 | Sweden | 2006 | NR | 408 | Median (range): 24 (22–27) | 157 (36.5) | MDI >27 |

| Dahlin et al,62 2005 | Sweden | 2001–2002 | 1, 3, 6 | 309 | Mean (range): 26.1 (18–44) | 126 (39.8) | DSM-IV criteria A and C |

| Kongsomboon,106 2010 | Thailand | 2008 | 1–6 | 593 | Mean (range): 20.7 (15–27) | 243 (41) | HRSRS ≥25 |

| Angkurawaranon et al,41 2016 | Thailand | 2013 | 2–6 | 1014 | Mean (SD): 20.8 (1.5) | 476 (46.9) | PHQ-9 ≥9 |

| N Wongpakaran and T Wongpakaran,177 2010 | Thailand | NR | 1–5 | 368 | Mean (SD): 20.8 (1) | 155 (42) | TDI >35 |

| Youssef,180 2016 | Trinidad and Tobago | NR | 1–3 | 381 | Mean (SD): 22.4 (3) | 126 (0.3) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Güleç et al,81 2005 | Turkey | 1993 | 1–6 | 668 | Mean (SD): 21.1 (2) | 658 (96.2) | BDI ≥17 |

| Akvardar et al,32 2003 | Turkey | 2002 | 1, 6 | 447 | Mean (SD): 21 (1.2) | 272 (39.1) | HADS-D ≥7 |

| Marakoğlu et al,115 2006 | Turkey | 2006 | 1–2 | 331 | Mean (SD): 19.5 (1.4) | 186 (56.2) | BDI ≥10 |

| Mayda et al,118 2010 | Turkey | 2009 | 1–5 | 202 | Mean (SD): 20.5 (2.2) | 85 (40.1) | BDI ≥17 |

| Yilmaz et al,178 2014 | Turkey | 2010 | 1–6 | 995 | Mean (SD): 21.1 (1.9) | 517 (52) | BDI ≥10 |

| Aktekin et al,196 2001 | Turkey | 1996–2002 | 1–2 | 119 | NR | NR | GHQ-12 ≥4 |

| Karaoğlu and Şeker,101 2011 | Turkey | 2008–2009 | 1–3 | 485 | Mean (SD): 19.5 (1.5) | 272 (56.1) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Baykan et al,50 2012 | Turkey | NR | 6 | 193 | Mean (SD): 24.5 (1.5) | 107 (55.4) | DASS-42 ≥10 |

| Akvardar et al,33 2004 | Turkey | NR | 1, 6 | 166 | NR | NR | HADS-D ≥7 |

| Kaya et al,102 2007 | Turkey | NR | NR | 352 | NR | 226 (64.2) | BDI ≥17 |

| Ahmed et al,30 2009 | UAE | 2008 | 1–5 | 165 | NR | 0 | BDI ≥10 |

| James et al,98 2013 | UK | 2007 | 1 | 324 | NR | 194 (60) | GHQ-12 ≥4 |

| Honney et al,88 2010 | UK | 2008 | NR | 553 | Mean (SD): 21.6 (3) | 220 (39.8) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Ashton and Kamali,44 1995 | UK | 1993–1994 | 2 | 186 | Mean (SD): 20.4 (1.8) | 77 (40.7) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Newbury-Birch et al,204 2001 | UK | 1995, 1998 | 5 | 114 | NR | 38 (33.3) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Quince et al,206 2012 | UK | 2007–2010 | 1–6 | 2155 | NR | 122 (43.2) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Guthrie et al,201 1998 | UK | NR | 1 | 172 | NR | 88 (51.2) | GHQ-12 ≥4 |

| Pickard et al,135 2000 | UK | NR | 2 | 136 | NR | 46 (33.8) | HADS-D ≥8 |

| Herzog et al,86 1987 | US | 1985 | 1–2 | 200 | Mean (range): 23.1 (19–31) | NR | BDI ≥10 |

| Hendryx et al,85 1991 | US | 1988 | 1 | 110 | Mean (SD): 24.1 (3.1) | 70 (63.6) | BDI ≥10 |

| Givens and Tjia,78 2002 | US | 1994 | 1–2 | 194 | NR | 83 (43) | BDI-SF ≥8 |

| Thomas et al,164 2007 | US | 2004 | 1–4 | 535 | NR | 248 (45.4) | PRIME-MD |

| Dyrbye et al,72 2006 | US | 2004 | NR | 545 | NR | 245 (45) | PRIME-MD |

| Shah et al,149 2009 | US | 2005 | 1–4 | 2683 | Mean (SD): 26 (3.2) | 1076 (40) | CES-D ≥19 |

| Dyrbye et al,71 2007 | US | 2006 | 1–4 | 1691 | NR | 777 (46) | PRIME-MD |

| Smith et al,159 2011 | US | 2008 | 1–5 | 480 | Mean (range): 26.3 (18–51) | 480 (100) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Smith et al,158 2010 | US | 2008 | 1–5 | 844 | Mean (SD): 25.7 (4.1) | 844 (100) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Shindel et al,155 2011 | US | 2008 | 1–5 | 1241 | Mean (SD): 25.4 (3.4) | 0 | CES-D ≥16 |

| Schwenk et al,146 2010 | US | 2009 | 1–4 | 504 | NR | 210 (41.6) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Wimsatt et al,175 2015 | US | 2009 | 1–4 | 505 | NR | 210 (41.6) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Dyrbye et al,69 2010 | US | 2009 | 1–4 | 2661 | NR | 1352 (51.4) | PRIME-MD |

| Chang et al,59 2012 | US | 2010 | 1–3 | 364 | NR | 160 (44) | PRIME-MD |

| Jackson et al,96 2016 | US | 2012 | 1–4 | 4354 | Median (range): 25 (22–32) | 1957 (45.3) | PRIME-MD |

| Dyrbye et al,68 2015 | US | 2012 | 2–4 | 870 | NR | 442 (50.9) | PRIME-MD |

| Thompson et al,166 2016 | US | 2013 | 1–4 | 153 | NR | 75 (46.6) | PHQ-9 ≥10 |

| Gold et al,80 2015 | US | 2013 | 1–5 | 183 | NR | 79 (43.2) | PRIME-MD |

| Lapinski et al,109 2016 | US | 2014 | 1–4 | 1294 | NR | 681 (52.6) | PHQ-9 ≥5 |

| Zoccolillo et al,183 1986 | US | 1982–1984 | 1–2 | 304 | NR | NR | BDI ≥10 |

| Vitaliano et al,208 1988 | US | 1984–1985 | 1 | 312 | Mean (SD): 25.6 (3.5) | 196 (63) | BDI ≥5 |

| Rosal et al,207 1997 | US | 1987–1993 | 2 | 171 | NR | 140 (51) | CES-D ≥80th percentile |

| Camp et al,198 1994 | US | 1991–1993 | 1 | 232 | NR | 153 (65.9) | Zung-SDS ≥50 |

| Mosley et al,123 1994 | US | 1992–1993 | 3 | 69 | Mean (range): 26 (24–37) | 47 (68) | CES-D ≥16 |

| Levine et al,202 2006 | US | 2000–2003 | 2 | 330 | NR | NR | BDI ≥8 |

| Tjia et al,168 2005 | US | 2001–2002 | 1–4 | 322 | Mean (SD): 25.3 (2.6) | 175 (54.4) | BDI-SF ≥8 |

| Thompson et al,165 2010 | US | 2002–2003 | 3 | 44 | NR | NR | CES-D ≥16 |

| Goebert et al,79 2009 | US | 2003–2004 | 1–4 | 1184 | NR | NR | CES-D ≥16 |

| Dyrbye et al,70 2011 | US | 2006, 2007, 2009 | 4 | 1428 | NR | NR | PRIME-MD |

| Haglund et al,10 2009 | US | 2006–2007 | 3 | 101 | Mean (SD): 25.4 (2.2) | 47 (47) | BDI-II ≥14 |

| Dyrbye et al,73 2008 | US | 2006–2007 | 1–4 | 2228 | NR | 1159 (51.6) | PRIME-MD |

| Ghodasara et al,77 2011 | US | 2008–2009 | 1–3 | 301 | NR | 154 (51) | BDI-II ≥14 |

| Hardeman et al,83 2015 | US | 2010–2011 | 1 | 3149 | NR | 1592 (49.4) | PROMIS-T >60 |

| Ludwig et al,203 2015 | US | 2010–2014 | 3 | 336 | NR | NR | CES-D >16 |

| Dyrbye et al,74 2014 | US | 2011–2012 | 1–4 | 4402 | Median: 25 | 1972 (45.1) | PRIME-MD |

| Wolf and Rosenstock,176 2016 | US | 2012–2013 | 1–4 | 130 | NR | NR | PRIME-MD |

| Mousa et al,124 2016 | US | 2013–2014 | 1–4 | 336 | NR | NR | PRIME-MD |

| Clark and Zeldow,199 1988 | US | NR | 2 | 110 | Mean (SD): 23.6 (2.9) | 80 (73) | BDI ≥8 |

| MacLean et al,112 2016 | US | NR | 1–4 | 385 | NR | NR | PRIME-MD |

| Chandavarkar et al,58 2007 | US | NR | 1–4 | 427 | NR | 145 (34) | BDI-II ≥21 |

| Zeldow et al,182 1987 | US | NR | NR | 99 | Mean: 25.4 | 67 (67.7) | BDI-II ≥14 |

| Smith et al,157 2007 | US | NR | NR | 438 | Mean (SD): 24.8 (2.8) | 318 (72.6) | BDI ≥10 |

Abbreviations: ADS-K, General Depression Scale Short Form (in German); AKUADS, Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-SF, BDI Short Form; BSI-DEP, Brief Symptom Inventory Depression; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; DSP, Derogatis Stress Profile; EST-Q, Emotional State Questionnaire; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HRSRS, Health-Related Self-Reported Scale; K-10, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; KADS, Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale; MDI, Major Depression Inventory; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MMPI-D, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Depression Scale; NR, not reported; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; PROMIS-T, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; QIDS, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; SCL-90, 90-item Symptom Checklist; TDI, Thai Depression Inventory; UAE, United Arab Emirates; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; Zung-SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; Zung-SF, Zung-SDS Short Form.

Studies are ordered alphabetically by country and then by year of survey.

Table 2.

Selected Characteristics of the 24 Studies of Suicidal Ideationa

| Source | Country | Survey Years | Year of Training | No. of Students | Age, y | Men, No. (%) | Instrument and Cutoff Score or Descriptionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Melo Cavestro and Rocha,65 2006 | Brazil | 2003 | 1–6 | 213 | Mean (SD): 23.1 (2.3) | 109 (51.2) | MINI |

| Alexandrino-Silva et al,34 2009 | Brazil | 2006–2007 | 1–6 | 336 | Mean (SD): 22.4 (2.5) | 105 (31) | BSI >0 |

| Chen et al,188 2004 | China | 2002 | 2–3 | 892 | Mean (SD): 17.5 (0.4) | 0 | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

| Wan et al,4 2012 | China | 2010 | 1–5 | 4063 | Mean (SD): 20.5 (1.1) | 1895 (46.6) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

| Sobowale et al,160 2014 | China | 2012 | 2–3 | 348 | NR | NR | Suicidal ideation over past 2 wk (PHQ-9) |

| Ahmed et al,185 2016 | Egypt | 2016 | NR | 612 | Mean (SD): 21.2 (1.6) | 190 (31) | BSI >24 |

| Okasha et al,192 1981 | Egypt | 1978–1979 | 5 | 516 | NR | NR | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

| Alem et al,186 2005 | Ethiopia | 2001 | NR | 273 | NR | 227 (83.2) | Suicidal ideation over past 1 mo |

| Wege et al,174 2016 | Germany | 2012–2013 | 1 | 590 | Mean (SD): 21.1 (3.9) | 177 (29.9) | Suicidal ideation over past 2 wk (PHQ-9) |

| Tin et al,167 2015 | Malaysia | 2013 | 1–5 | 517 | NR | 188 (35) | SBQ-R ≥7 |

| Eskin et al,189 2011 | Multiple | NR | 1–6 | 646 | Mean: 21.4 | 353 (54.6) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

| Menezes et al,191 2012 | Nepal | 2010 | 2–3 | 206 | Mean (SD): 21 (1.7) | 112 (54.4) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (GHQ-28) |

| Tyssen et al,194 2001 | Norway | 1993–1994 | 6 | 522 | Mean (SD): 28 (2.8) | 224 (43) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (Paykel Inventory) |

| Osama et al,5 2014 | Pakistan | 2013 | 1–5 | 331 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (1.7) | 135 (41.2) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (GHQ-28) |

| Khokher and Khan,190 2005 | Pakistan | NR | 1–5 | 217 | Mean: 22.6 | 96 (44.2) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (GHQ-28) |

| Wallin and Runeson,195 2003 | Sweden | 1998 | 1, 5 | 305 | Mean: 27.4 | 127 (41.6) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

| Dahlin et al,62 2005 | Sweden | 2001–2002 | 1, 3, 6 | 296 | Mean (range): 26.1 (18–44) | 126 (39.8) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (Meehan Inventory) |

| Amiri et al,187 2013 | United Arab Emirates | NR | 1–6 | 115 | Mean (SD): 20.7 (2.1) | 47 (40.9) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

| Thompson et al,165 2010 | US | 2002–2003 | 3 | 43 | NR | NR | Suicidal ideation over past 2 wk (PRIME-MD) |

| Goebert et al,79 2009 | US | 2003–2004 | 1–4 | 1215 | NR | NR | Suicidal ideation over past 2 wk (PRIME-MD) |

| Dyrbye et al,73 2008 | US | 2006–2007 | 1–4 | 2230 | NR | 1159 (51.6) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (Meehan Inventory) |

| Dyrbye et al,74 2014 | US | 2011–2012 | 1–4 | 4032 | Median: 25 | 1972 (45.1) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (Meehan Inventory) |

| MacLean et al,112 2016 | US | NR | 1–4 | 385 | NR | NR | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo (Meehan Inventory) |

| Tran et al,193 2015 | Vietnam | 2009 | 1, 3, 5 | 2099 | Mean (range): 21.5 (18–30) | 1052 (50.1) | Suicidal ideation over past 12 mo |

Abbreviations: BSI, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NR, not reported; PHQ-9, 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; SBQ-R, Revised Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire; US, United States.

Studies are ordered alphabetically by country and then by year of survey.

Studies for which a specific instrument is not specified used variably worded short form screening instruments.

Medical student training level, continent or region, country, diagnostic criteria or screening instrument cutoff, and total Newcastle-Ottawa scores for the studies appear in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Newcastle-Ottawa score components for all 195 individual studies appear in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

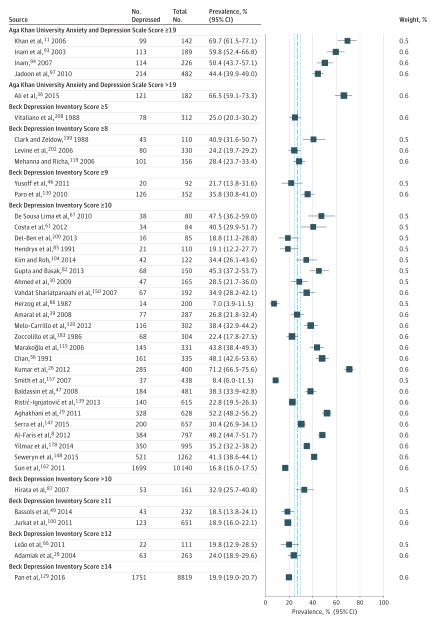

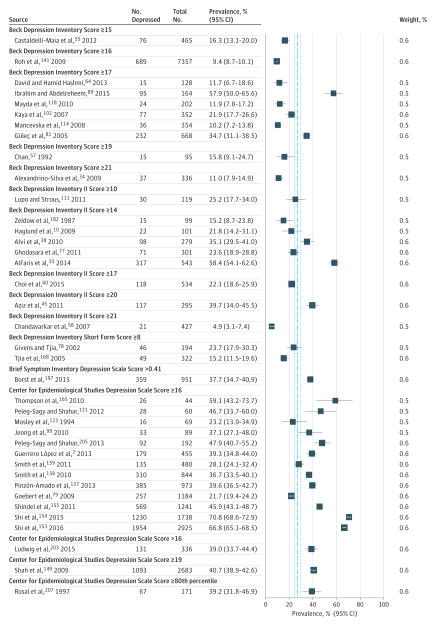

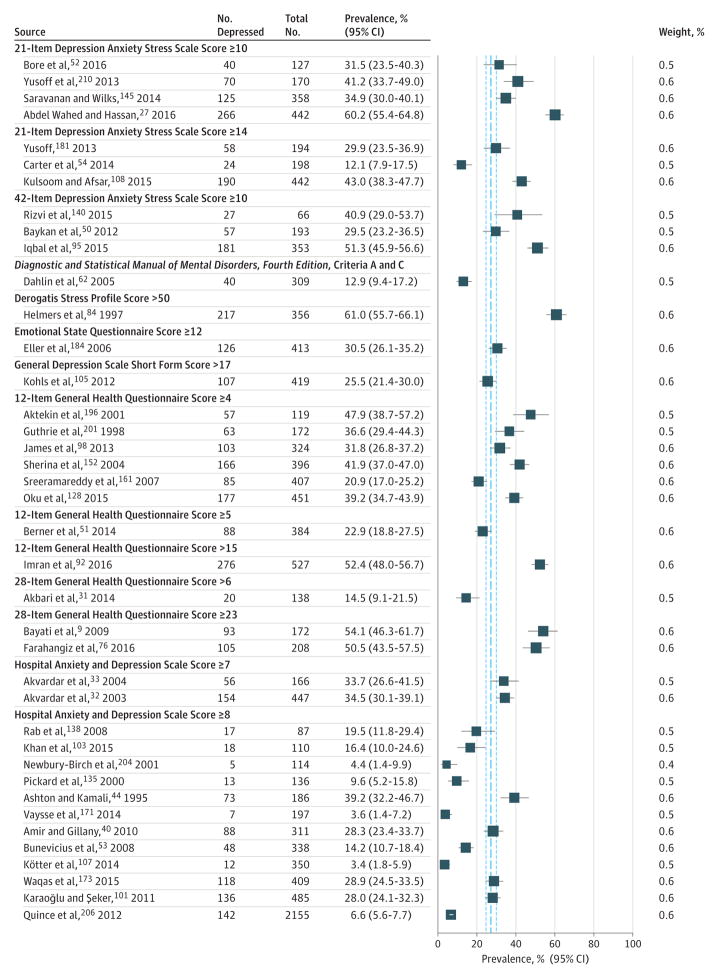

Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students

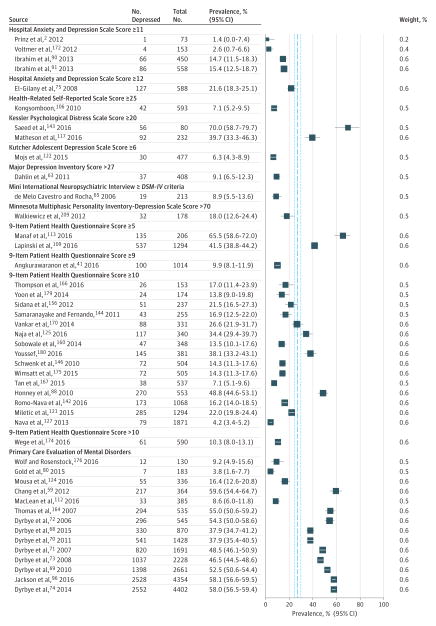

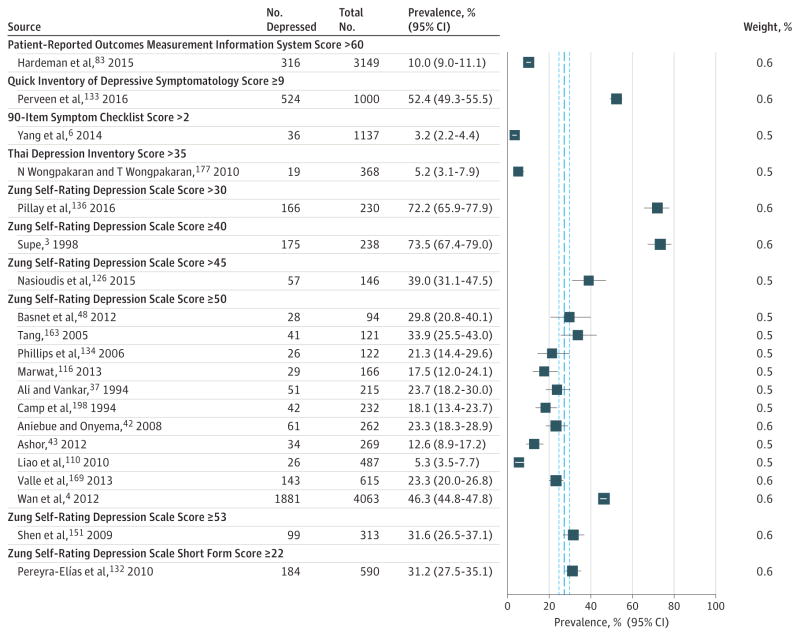

Meta-analytic pooling of the prevalence estimates of depression or depressive symptoms reported by 183 studies yielded a crude summary prevalence of 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals; 95% CI, 24.7%–29.9%), with significant evidence of between-study heterogeneity (Q = 16721.1, τ2 = 0.78, I2 = 98.9%, P < .001) (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). The prevalence estimates reported by the individual studies ranged from 1.4% to 73.5%. Sensitivity analysis, in which the meta-analysis was serially repeated after exclusion of each study, demonstrated that no individual study affected the overall prevalence estimate by more than 0.3% (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis by Scores on the Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory.

The vertical dashed lines indicate the pooled summary estimate (95% CI) for all studies in Figures 2–6: 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals); 95% CI, 24.7%–29.9%; I2 = 98.9%, τ2 = 0.78, P < .001. The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimate. The studies in Figures 2–6 are ordered alphabetically by screening instrument and then sorted by increasing sample size within each instrument.

Figure 3. Meta-analysis by Scores on the First, Second, and Short Form Versions of the Beck Depression Inventory, Brief Symptom Inventory Depression Scale, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

The vertical dashed lines indicate the pooled summary estimate (95% CI) for all studies in Figures 2–6: 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals); 95% CI, 24.7%–29.9%; I2 = 98.9%, τ2 = 0.78, P < .001. The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimate. The studies in Figures 2–6 are ordered alphabetically by screening instrument and then sorted by increasing sample size within each instrument.

Figure 4. Meta-analysis by Scores on the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Criteria A and C, Derogatis Stress Profile, Emotional State Questionnaire, General Depression Scale Short Form, General Health Questionnaire, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

The vertical dashed lines indicate the pooled summary estimate (95% CI) for all studies in Figures 2–6: 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals); 95% CI, 24.7%–29.9%; I2 = 98.9%, τ2 = 0.78, P < .001. The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimate. The studies in Figures 2–6 are ordered alphabetically by screening instrument and then sorted by increasing sample size within each instrument.

Figure 5. Meta-analysis by Scores on Several Scales.

The vertical dashed lines indicate the pooled summary estimate (95% CI) for all studies in Figures 2–6: 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals); 95% CI, 24.7%–29.9%; I2 = 98.9%, τ2 = 0.78, P < .001. The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimate. The studies in Figures 2–6 are ordered alphabetically by screening instrument and then sorted by increasing sample size within each instrument. DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Figure 6. Meta-analysis by Scores on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, 90-Item Symptom Checklist, Thai Depression Inventory, and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale.

The vertical dashed lines indicate the pooled summary estimate (95% CI) for all studies in Figures 2–6: 27.2% (37 933/122 356 individuals); 95% CI, 24.7%–29.9%; I2 = 98.9%, τ2 = 0.78, P < .001. The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals of the estimate. The studies in Figures 2–6 are ordered alphabetically by screening instrument and then sorted by increasing sample size within each instrument.

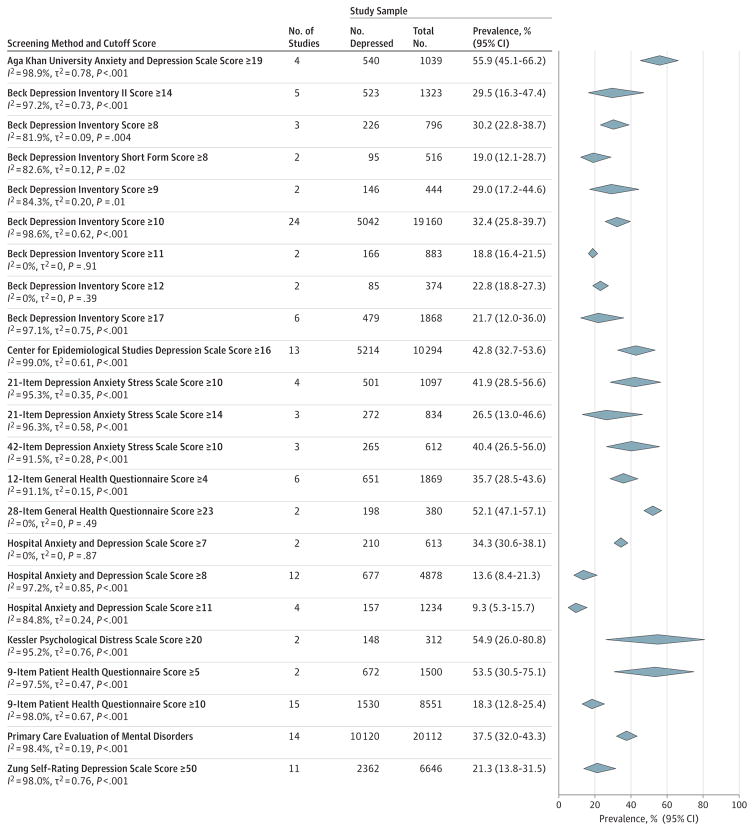

To further characterize the range of depression or depressive symptom prevalence estimates identified by these methodologically diverse studies, meta-analyses stratified by screening instrument and cutoff score were conducted (Figure 7). Summary prevalence estimates ranged from 9.3% (157/1234 individuals [95% CI, 5.3%–15.7%]; Q = 19.7, τ2 = 0.24, I2 = 84.8%) for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale with a cutoff score of 11 or greater to 55.9% (540/1039 individuals [95% CI, 45.1%–66.2%]; Q = 32.9, τ2 = 0.18, I2 = 90.9%) for the Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale with a cutoff score of 19 or greater. The median summary prevalence was 32.4% (5042/19 160 individuals [95% CI, 25.8%–39.7%]; Q = 1665.3, τ2 = 0.62, I2 = 98.6%) for the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) with a cutoff score of 10 or greater.

Figure 7. Meta-analyses of the Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students Stratified by Screening Instrument and Cutoff Score.

Pooled summary estimates are ordered alphabetically by screening instrument. The individual studies contributing to each summary estimate are reported in Figures 2 through 6. The area of each diamond is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal extremes of the diamonds indicate 95% CIs of the estimate.

Among medical students who screened positive for depression,15.7%(110/954 individuals [95%CI,10.2%–23.4%]; Q = 20.1, τ2 = 0.26, I2 = 70.1%) reportedly sought psychiatric or other mental health treatment as assessed by a subset of 7 studies reporting this information (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

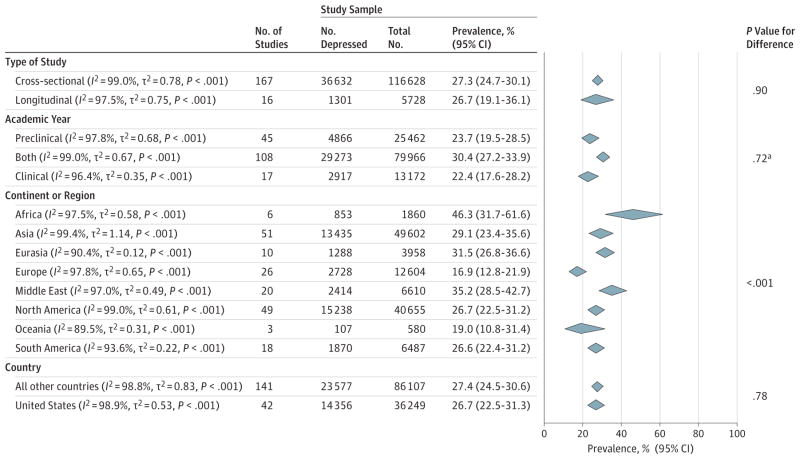

Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms by Study-Level Characteristics

No statistically significant differences in prevalence estimates were noted between cross-sectional studies (36 632/116 628 [27.3%; 95%CI, 24.7%–30.1%]) and longitudinal studies (1301/5728 [26.7%; 95%CI, 19.1%–36.1%]) (test for subgroup differences, Q = 0.02, P = .90) or studies performed in the United States (14 356/36 249 [26.7%; 95% CI, 22.5%–31.3%]) compared with those performed outside the United States (23 577/86 107 [27.4%; 95% CI, 24.5%–30.6%]) (Q = 0.08, P = .78). Studies were further stratified by continent or region in Figure 8. Prevalence estimates from studies limited to preclinical students (4866/25 462 [23.7%; 95% CI, 19.5%–28.5%]) did not significantly differ from estimates from studies limited to clinical students (2917/13 172 [22.4%; 95% CI, 17.6%–28.2%]) (Q = 0.13, P = .72).

Figure 8. Meta-analyses of the Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students Stratified by Study-Level Characteristics.

The area of each diamond is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal extremes of the diamonds indicate 95% CIs of the estimate.

aComparison of studies reporting only on preclinical students with those studies reporting only on clinical students.

Prevalence estimates did not significantly vary with baseline survey year (survey year range, 1982–2015; slope = 0.2% 1-year increase [95%CI, −0.2%to0.7%]; Q = 1.17, P = .28). There Were no significant associations between prevalence and mean or median age (slope = 0.2%per 1-year increase [95%CI, −1.4% to 1.8%]; Q = 0.07, P = .79) or sex (slope = −1.1% per percentage increase in male study participants [95% CI, −15.9% to 13.7%]; Q = 0.02, P = .88).

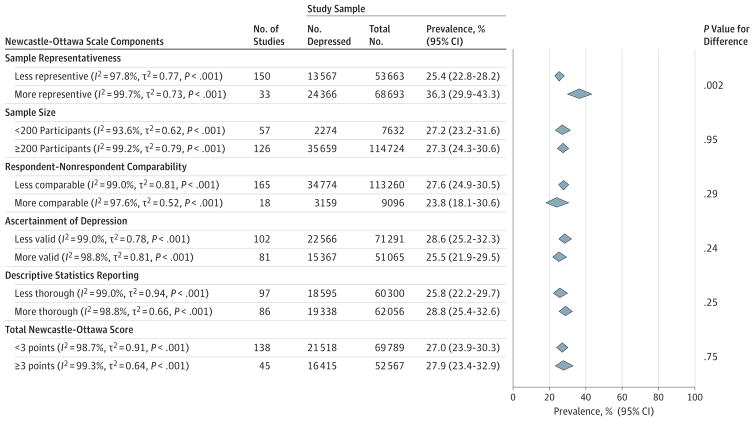

When evaluated by Newcastle-Ottawa criteria, higher prevalence estimates were found among studies with more representative participant populations (24 366/68 693; 36.3% [95%CI, 29.9%–43.3%]) compared with those with less representative participant populations (13 567/53 663; 25.4% [95% CI, 22.8%–28.2%]) (Q = 9.6, P = .002; Figure 9). There were no statistically significant differences in prevalence estimates when studies were stratified by sample size, respondent and nonrespondent comparability, validity of ascertainment of depression or depressive symptoms (details regarding determination of screening instrument validity appear in eMethods 2 in the Supplement), thoroughness of descriptive statistics reporting, or total Newcastle-Ottawa score (P > .05 for all comparisons).

Figure 9. Meta-analyses of the Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students Stratified by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Components and Total Score.

Full details regarding Newcastle-Ottawa risk of bias scoring are provided in eMethods 2 in the Supplement. Component scores for all individual studies are presented in eTable 2 in the Supplement. The area of each diamond is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal extremes of the diamonds indicate 95% CIs of the estimate.

Heterogeneity Within Depression Screening Instruments

To identify potential sources of heterogeneity independent of assessment modality, heterogeneity was examined within subgroups of studies using common instruments when at least 6 studies were available (complete results appear in eTable 4 in the Supplement). No significant differences between cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were observed within any instruments when at least 3 studies were in each comparator subgroup.

Heterogeneity was partially accounted for by country with US studies yielding lower depression or depressive symptom prevalence estimates than non-US studies among the 24 studies using the BDI and a cutoff score of 10 or greater (13.0% vs 37.5%, respectively; Q = 12.7, P < .001) and the 13 studies using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and a cutoff score of 16 or greater (34.4% vs 50.3%; Q = 3.8, P = .05). However, this difference was not seen among other instruments.

Level of training did not significantly contribute to between study heterogeneity among any of the examined instruments. Year of baseline survey significantly contributed to observed statistical heterogeneity among 3 instruments, although the results were inconsistent (ie, 2 analyses suggested that depression was increasing with time, whereas a third suggested it was decreasing). Age and sex were not significantly associated with depression prevalence among any instruments.

Analysis of Longitudinal Studies

The temporal relationship between exposure to medical school and depressive symptoms was assessed in an analysis of 9 longitudinal studies that measured depressive symptoms before and during medical school (Table 3). Because studies used different assessment instruments, the relative change in depressive symptoms was calculated for each study individually (ie, follow-up prevalence divided by baseline prevalence) and then the relative changes derived from the individual studies were examined. Overall, the median absolute increase in depressive symptoms was 13.5% (range, 0.6%–35.3%) following the onset of medical training.

Table 3.

Secondary Analysis of 9 Longitudinal Studies Reporting Depression or Depressive Symptom Prevalence Estimates Both Before and During Medical School

| Sourcea | Screening Instrument | Cutoff Score | Follow-up, mo | Baseline

|

Follow-up

|

Comparison

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Depressed | Sample Size | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | No. Depressed | Sample Size | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | Absolute Increase, % (95% CI) | Relative Increase, Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Walkiewicz et al,209 2012 | MMPI-D | >70 | 12 | 31 | 178 | 17.4 (11.8 to 23.0) | 32 | 178 | 18.0 (12.4 to 23.6) | 0.6 (−7.4 to 8.5) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Quince et al,206 2012 | HADS-D | ≥8 | 12 | 38 | 665 | 5.7 (3.9 to 7.5) | 36 | 429 | 8.4 (5.8 to 11.0) | 2.7 (−0.4 to 6.1) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Levine et al,202 2006 | 21-Item BDI | ≥8 | 20 | 64 | 376 | 17.0 (13.2 to 20.8) | 80 | 330 | 24.2 (19.6 to 28.8) | 7.2 (1.3 to 13.2) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Camp et al,198 1994 | Zung-SDS | ≥50 | 3 | 14 | 232 | 6.0 (2.9 to 9.1) | 42 | 232 | 18.1 (13.2 to 23.1) | 12.1 (6.2 to 18.0) | 3.0 (1.6 to 5.6) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Vitaliano et al,208 1988 | BDI | ≥5 | 8 | 36 | 312 | 11.5 (8.0 to 15.0) | 78 | 312 | 25.0 (20.2 to 29.8) | 13.5 (7.4 to 19.4) | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.3) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Clark and Zeldow,199 1988 | 21-item BDI | ≥8 | 14 | 11 | 116 | 9.5 (4.2 to 14.8) | 24 | 88 | 27.3 (18.0 to 36.6) | 17.8 (7.2 to 28.7) | 2.9 (1.3 to 6.2) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Rosal et al,207 1997 | CES-D | ≥80thb | 18 | 48 | 264 | 18.2 (13.6 to 22.9) | 67 | 171 | 39.2 (31.9 to 46.5) | 21.0 (12.3 to 29.6) | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.3) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Aktekin et al,196 2001 | GHQ | ≥4 | 12 | 21 | 119 | 17.6 (10.8 to 24.4) | 57 | 119 | 47.9 (38.9 to 56.9) | 30.3 (18.5 to 40.9) | 2.7 (1.5 to 4.8) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Yusoff et al,210 2013 | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 12 | 10 | 170 | 5.9 (2.4 to 9.4) | 70 | 170 | 41.2 (33.8 to 48.6) | 35.3 (26.8 to 43.3) | 7.0 (3.5 to 14.0) |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DASS-21, 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MMPI-D, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Depression Scale; Zung-SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale

Studies are sorted by the percentage increase in depressive symptoms from baseline to the follow-up survey. The median percentage increase among the studies was 13.5%.

Indicates 80th percentile.

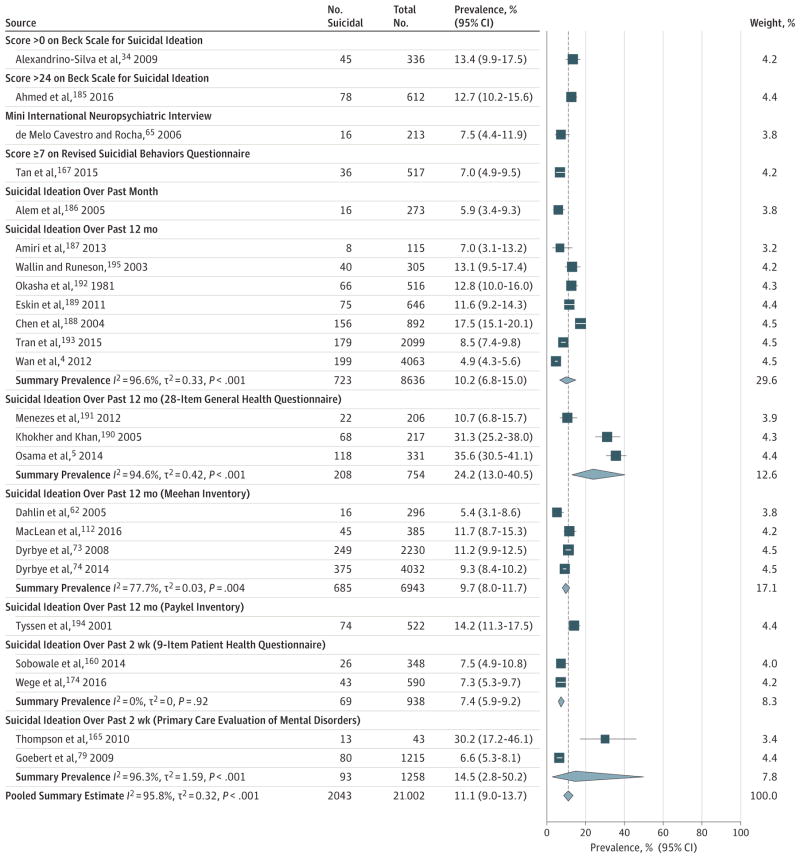

Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students

In an analysis of 24 studies, the crude summary prevalence of suicidal ideation, variably reported as having occurred over the past 2 weeks to the past 12 months, was 11.1% (2043/21 002 individuals; 95%CI, 9.0%–13.7%), with significant evidence of between-study heterogeneity (Q = 547.1, τ2 = 0.32, I2 = 95.8%, P < .001) (Figure 10). The prevalence estimates reported by the individual studies ranged from 4.9% to 35.6%. Sensitivity analysis showed that no individual study affected the overall pooled estimate by more than 1.9%(eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Figure 10. Meta-analysis of the Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students.

Contributing studies are stratified by screening modality and sorted by increasing sample size. The dotted line marks the overall summary estimate for all studies, 11.1% (2043/21 002 individuals; 95% CI, 9.0%–13.7%; Q = 547.1, τ2 = 0.32, I2 = 95.8%, P < .001). The area of each square is proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs of the estimate.

To further characterize the range of the suicidal ideation prevalence estimates identified, stratified meta-analyses were performed by screening instrument and cutoff score. Summary prevalence estimates ranged from 7.4% (69/938 individuals [95% CI, 5.9%–9.2%]; Q = 0.01, τ2 = 0, I2 = 0%) over the past 2 weeks for studies using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to 24.2% (208/754 individuals [95% CI, 13.0%–40.5%]; Q = 37.2, τ2 = 0.42, I2 = 94.6%) over the past 12 months for studies using the 28-item General Health Questionnaire.

The median prevalence of suicidal ideation over the past 12 months reported by 7 studies using variably worded short-form screening instruments was 10.2% (723/8636 individuals [95% CI, 6.8%–15.0%]; Q = 176.5, τ2 = 0.33, I2 = 96.6%). Among the full set of studies, no statistically significant differences in prevalence estimates were noted by country (United States vs other countries), continent or region, level of training, baseline survey year, average age, proportion of male study participants, or total Newcastle-Ottawa score (P > .05 for all comparisons). Within-instrument heterogeneity was not examined because there were not enough studies using identical screening instruments (≤4 for each assessment modality), precluding meaningful analysis.

Assessment of Publication Bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot of studies reporting on depression or depressive symptoms revealed significant asymmetry (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). There was evidence of publication bias, with smaller studies yielding more extreme prevalence estimates (P = .001 using the Egger test). The funnel plot of studies reporting on suicidal ideation revealed minimal asymmetry (eFigure 3 in the Supplement), suggesting the absence of significant publication bias (P = .49 using the Egger test).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 195 studies involving 129 123 medical students in 47 countries demonstrated that 27.2% (range, 9.3%–55.9%) of students screened positive for depression and that 11.1% (range, 7.4%–24.2%) reported suicidal ideation during medical school. Only 15.7% of students who screened positive for depression reportedly sought treatment. These findings are concerning given that the development of depression and suicidality has been linked to an increased short-term risk of suicide as well as a higher long-term risk of future depressive episodes and morbidity.211,212

The present analysis builds on recent work demonstrating a high prevalence of depression among resident physicians, and the concordance between the summary prevalence estimates (27.2% in students vs 28.8% in residents) suggests that depression is a problem affecting all levels of medical training.13,213 Taken together, these data suggest that depressive and suicidal symptoms in medical trainees may adversely affect the long-term health of physicians as well as the quality of care delivered in academic medical centers.214–216

When interpreting these findings, it is important to recognize that the data synthesized in this study were almost exclusively derived from self-report inventories of depressive symptoms that varied substantially in their sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing major depressive disorder (eTable 6 in the Supplement).217 Instruments such as the PHQ-9 have high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing major depression, whereas others such as the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) have low specificity and should be viewed as screening tools. Although these self-report measures of depressive symptoms have limitations, they are essential tools for accurately measuring depression in medical trainees because they protect anonymity in a manner that is not possible through formal diagnostic interviews.218 To control for the differences in these inventories, we stratified our analyses by survey instrument and cutoff score, identifying a range of estimates not captured in another evidence synthesis.219

The prevalence of depressive symptoms among medical students in this study was higher than that reported in the general population.220–222 For example, the National Institute of Mental Health study of behavioral health trends in the United States, including 67 500 nationally representative participants, found that the 12-month prevalence of a major depressive episode was 9.3% among 18- to 25-yearolds and 7.2% among 26- to 49-year-olds.220 In contrast, the BDI, CES-D, and PHQ-9 summary estimates obtained in the present study were between 2.2 and 5.2 times higher than these estimates. These findings suggest that depressive symptom prevalence is substantially higher among medical students than among individuals of similar age in the general population.

How depression levels in medical students compare with those in nonmedical undergraduate students and professional students is unclear. One review concluded that depressive symptom prevalence did not statistically differ between medical students and nonmedical undergraduate students.223 However, this conclusion may be confounded because the analysis did not control for assessment modality and did not include a comprehensive or representative set of studies (only 12 studies and 4 studies exclusively composed of medical students and nonmedical students, respectively). Two large, representative epidemiological studies have estimated that depressive symptom prevalence in nonmedical students ranges from 13.8% to 21.0%, lower than the estimates reported by many studies of medical students in the present meta-analysis.224,225

Some professional students, such as law students, may not markedly differ from medical students in their susceptibility to depression, although firm conclusions cannot be drawn from the currently available data.226,227 Together, these findings suggest that factors responsible for depression in medical students may also be operative in other undergraduate and professional schools. The finding in the longitudinal analysis of an increase in depressive symptom prevalence with the onset of medical school suggests that it is not just that medical students (and other students) are prone to depression, but that the school experience may be a causal factor.

This analysis identified a pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation of 11.1%. Endorsement of suicidal ideation as assessed by the PHQ-9 or other similar instruments increases the cumulative risk of a suicide attempt or completion over the next year by 10- and 100-fold, respectively.228 Combined with the finding that only 15.7%of medical students who screened positive for depression sought treatment, the high prevalence of suicidal ideation underscores the need for effective preventive efforts and increased access to care that accommodate the needs of medical students and the demands of their training.

Limitations

This study has important limitations. First, the data were derived from studies that had different designs, screening instruments, and trainee demographics. The substantial heterogeneity among the studies remained largely unexplained by the variables inspected. Second, many subgroup analyses relied on unpaired cross-sectional data collected at different medical schools, which may cause confounding. Third, because the studies were heterogeneous with respect to screening inventories and student populations, the prevalence of major depression could not be determined. Fourth, the analysis relied on aggregated published data. A multicenter, prospective study using a single validated measure of depression and suicidal ideation with structured diagnostic interviews in a random subset of participants would provide a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation among medical students.

Future Directions

Because of the high prevalence of depressive and suicidal symptomatology in medical students, there is a need for additional studies to identify the root causes of emotional distress in this population. To provide more relevant information, future epidemiological studies should consider adopting prospective study designs so that the same individuals can be assessed over time, use commonly used screening instruments with valid cutoffs for assessing depression in the community (eg, the BDI, CES-D, or PHQ-9), screen for comorbid anxiety disorders, and completely and accurately report their data, for example, by closely following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.229

Possible causes of depressive and suicidal symptomatology in medical students likely include stress and anxiety secondary to the competitiveness of medical school.62 Restructuring medical school curricula and student evaluations (such as using a pass-fail grading schema rather than a tiered grading schema and fostering collaborative group learning through a “flipped-classroom” education model) might ameliorate these stresses.230,231 Future research should also determine how strongly depression in medical school predicts depression during residency and whether interventions that reduce depression in medical students carry over in their effectiveness when those students transition to residency.232 Furthermore, efforts are continually needed to reduce barriers to mental health services, including addressing the stigma of depression.146,233

Conclusions

In this systematic review, the summary estimate of the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical studentswas27.2%andthatof suicidal ideationwas11.1%. Further research is needed to identify strategies for preventing and treating these disorders in this population.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

Are medical students at high risk for depression and suicidal ideation?

Findings

In this meta-analysis, the overall prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical students was 27.2%, and the overall prevalence of suicidal ideation was 11.1%. Among medical students who screened positive for depression, 15.7% sought psychiatric treatment.

Meaning

The overall prevalence of depressive symptoms among medical students in this study was higher than that reported in the general population, which underscores the need for effective preventive efforts and increased access to care for medical students.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health (MSTP TG 2T32GM07205 awarded to Mr Ramos and grant R01MH101459 awarded to Dr Sen) and the US Department of State (Fulbright Scholarship awarded to Dr Mata).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The National Institutes of Health and the US Department of State had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclaimer: The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the National Institutes of Health and the US Department of State.

Author Contributions: Dr Mata had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Ms Rotenstein, Messrs Ramos and Segal, and Dr Torre are equal contributors.

Concept and design: Mata.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Mata.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Mata.

Obtained funding: Guille, Sen, Mata.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Guille, Sen, Mata.

Study supervision: Guille, Sen, Mata.

References

- 1.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–373. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prinz P, Hertrich K, Hirschfelder U, de Zwaan M. Burnout, depression and depersonalisation—psychological factors and coping strategies in dental and medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29(1):Doc10. doi: 10.3205/zma000780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Supe AN. A study of stress in medical students at Seth G S Medical College. J Postgrad Med. 1998;44(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan YH, Gao R, Tao XY, Tao FB, Hu CL. Relationship between deliberate self-harm and suicidal behaviors in college students [in Chinese] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2012;33(5):474–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osama M, Islam MY, Hussain SA, et al. Suicidal ideation among medical students of Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;27:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang F, Meng H, Chen H, et al. Influencing factors of mental health of medical students in China. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2014;34(3):443–449. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrero López JB, Heinze Martin G, Ortiz de León S, Cortés Morelos J, Barragán Pérez V, Flores-Ramos M. Factors that predict depression in medical students [in Spanish] Gac Med Mex. 2013;149(6):598–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Faris EA, Irfan F, Van der Vleuten CP, et al. The prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms from an Arabian setting: a wake up call. Med Teach. 2012;34(suppl 1):S32–S36. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.656755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayati A, Beigi M, Salehi M. Depression prevalence and related factors in Iranian students. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12(20):1371–1375. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2009.1371.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haglund ME, aan het Rot M, Cooper NS, et al. Resilience in the third year of medical school: a prospective study of the associations between stressful events occurring during clinical rotations and student well-being. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):258–268. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819381b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan MS, Mahmood S, Badshah A, Ali SU, Jamal Y. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and their associated factors among medical students in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56(12):583–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373–2383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr LK, Kerr LD., Jr Screening tools for depression in primary care: the effects of culture, gender, and somatic symptoms on the detection of depression. West J Med. 2001;175(5):349–352. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.5.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterne JAC, Jüni P, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Bartlett C, Egger M. Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in “meta-epidemiological” research. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1513–1524. doi: 10.1002/sim.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Stat Med. 2002;21(4):589–624. doi: 10.1002/sim.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JAC, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar GS, Jain A, Hegde S. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors using Beck Depression Inventory among students of a medical college in Karnataka. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54(3):223–226. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel Wahed WY, Hassan SK. Prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety and depression among medical Fayoum University students [published online February 20, 2016] Alex J Med. doi: 10.1016/j.ajme.2016.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adamiak G, Swiatnicka E, WołodŸko-Makarska L, Switalska MJ. Assessment of quality of life of medical students relative to the number and intensity of depressive symptoms [in Polish] Psychiatr Pol. 2004;38(4):631–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aghakhani N, Sharif Nia H, Eghtedar S, Rahbar N, Jasemi M, Mesgar Zadeh M. Prevalence of depression among students of Urmia University of Medical Sciences (Iran) Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2011;5(2):131–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed I, Banu H, Al-Fageer R, Al-Suwaidi R. Cognitive emotions: depression and anxiety in medical students and staff. J Crit Care. 2009;24(3):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akbari V, Hajian A, Damirchi P. Prevalence of emotional disorders among students of University of Medical Sciences; Iran. Open Psychol J. 2014;7:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akvardar Y, Demiral Y, Ergör G, Ergör A, Bilici M, Akil Ozer O. Substance use in a sample of Turkish medical students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72(2):117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akvardar Y, Demiral Y, Ergor G, Ergor A. Substance use among medical students and physicians in a medical school in Turkey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(6):502–506. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexandrino-Silva C, Pereira MLG, Bustamante C, et al. Suicidal ideation among students enrolled in healthcare training programs: a cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(4):338–344. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462009005000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AlFaris EA, Naeem N, Irfan F, Qureshi R, van der Vleuten C. Student centered curricular elements are associated with a healthier educational environment and lower depressive symptoms in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:192. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali FA, Javed N, Manzur F. Anxiety and depression among medical students during exams. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2015;9(1):119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali RV, Vankar GK. Psychoactive substance use among medical students. Indian J Psychiatry. 1994;36(3):138–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alvi T, Assad F, Ramzan M, Khan FA. Depression, anxiety and their associated factors among medical students. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20(2):122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.do Amaral GF, de Gomide LMP, de Batista MP, et al. Depressive symptoms in medical students of Universidade Federal de Goiás: a prevalence study [in Portuguese] Rev Psiquiatr RS. 2008;30(2):124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amir M, El Gillany AH. Self-reported depression and anxiety by students at an Egyptian medical school. J Pak Psychiatr Soc. 2010;7(2):71. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, Sachdev A, Wisetborisut A, Jangiam W, Uaphanthasath R. Predictors of quality of life of medical students and a comparison with quality of life of adult health care workers in Thailand. Springerplus. 2016;5:584. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aniebue PN, Onyema GO. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Nigerian medical undergraduates. Trop Doct. 2008;38(3):157–158. doi: 10.1258/td.2007.070202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashor AW. Smoking dependence and common psychiatric disorders in medical students: cross-sectional study. Pak J Med Sci. 2012;28(4):670–674. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashton CH, Kamali F. Personality, lifestyles, alcohol and drug consumption in a sample of British medical students. Med Educ. 1995;29(3):187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aziz NAHA, Al-Muwallad OK, Mansour EAK. Neurotic depression and chocolate among female medical students at College of Medicine, Taibah University Almadinah Almunawwarah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2011;6(2):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yusoff MSB, Rahim AFA, Yaacob MJ. The prevalence of final year medical students with depressive symptoms and its contributing factors. Int Med J. 2011;18(4):305–309. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baldassin S, Alves TC, de Andrade AG, Nogueira Martins LA. The characteristics of depressive symptoms in medical students during medical education and training: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basnet B, Jaiswal M, Adhikari B, Shyangwa PM. Depression among undergraduate medical students. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2012;10(39):56–59. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v10i3.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bassols AM, Okabayashi LS, Silva AB, et al. First- and last-year medical students: is there a difference in the prevalence and intensity of anxiety and depressive symptoms? Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2014;36(3):233–240. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baykan Z, Naçar M, Cetinkaya F. Depression, anxiety, and stress among last-year students at Erciyes University Medical School. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):64–65. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.11060125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berner JE, Santander J, Contreras AM, Gómez T. Description of internet addiction among Chilean medical students: a cross-sectional study. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(1):11–14. doi: 10.1007/s40596-013-0022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bore M, Kelly B, Nair B. Potential predictors of psychological distress and well-being in medical students: a cross-sectional pilot study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:125–135. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S96802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bunevicius A, Katkute A, Bunevicius R. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in medical students and in humanities students: relationship with big-five personality dimensions and vulnerability to stress. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(6):494–501. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carter FA, Bell CJ, Ali AN, McKenzie J, Wilkinson TJ. The impact of major earthquakes on the psychological functioning of medical students: a Christchurch, New Zealand study. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1398):54–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castaldelli-Maia JM, Martins SS, Bhugra D, et al. Does ragging play a role in medical student depression: cause or effect? J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan DW. Depressive symptoms and depressed mood among Chinese medical students in Hong Kong. Compr Psychiatry. 1991;32(2):170–180. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90010-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chan DW. Coping with depressed mood among Chinese medical students in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord. 1992;24(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chandavarkar U, Azzam A, Mathews CA. Anxiety symptoms and perceived performance in medical students. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(2):103–111. doi: 10.1002/da.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang E, Eddins-Folensbee F, Coverdale J. Survey of the prevalence of burnout, stress, depression, and the use of supports by medical students at one school. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(3):177–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.11040079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi J, Son SL, Kim SH, Kim H, Hong J-Y, Lee M-S. The prevalence of burnout and the related factors among some medical students in Korea [in Korean] Korean J Med Educ. 2015;27(4):301–308. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2015.27.4.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Costa EF, Santana YS, Santos ATR, Martins LA, Melo EV, Andrade TM. Depressive symptoms among medical intern students in a Brazilian public university [in Portuguese] Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2012;58(1):53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39(6):594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dahlin M, Nilsson C, Stotzer E, Runeson B. Mental distress, alcohol use and help-seeking among medical and business students: a cross-sectional comparative study. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.David MA, Hamid Hashmi SS. Study to evaluate prevalence of depression, sleep wake pattern and their relation with use of social networking sites among first year medical students. Int J Pharma Med Biol Sci. 2013;2(1):27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Melo Cavestro J, Rocha FL. Depression prevalence among university students [in Spanish] J Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;55(4):264–267. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leão PB, Martins LA, Menezes PR, Bellodi PL. Well-being and help-seeking: an exploratory study among final-year medical students. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2011;57(4):379–386. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Sousa Lima L, Ferry V, Martins Fonseca RN, et al. Depressive symptoms among medical students of the State University of Maranhão. Revista Neurociências. 2010;18(1):8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dyrbye LN, Eacker A, Durning SJ, et al. The impact of stigma and personal experiences on the help-seeking behaviors of medical students with burnout. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):961–969. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Jr, Eacker A, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dyrbye LN, Moutier C, Durning SJ, et al. The problems program directors inherit: medical student distress at the time of graduation. Med Teach. 2011;33(9):756–758. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.577468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2103–2109. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huntington JL, et al. Personal life events and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):374–384. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Gilany AH, Amr M, Hammad S. Perceived stress among male medical students in Egypt and Saudi Arabia: effect of sociodemographic factors. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28(6):442–448. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Farahangiz S, Mohebpour F, Salehi A. Assessment of mental health among Iranian medical students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2016;10(1):49–55. doi: 10.12816/0031216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghodasara SL, Davidson MA, Reich MS, Savoie CV, Rodgers SM. Assessing student mental health at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):116–121. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ffb056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Givens JL, Tjia J. Depressed medical students’ use of mental health services and barriers to use. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):918–921. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goebert D, Thompson D, Takeshita J, et al. Depressive symptoms in medical students and residents: a multischool study. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):236–241. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819391bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gold JA, Johnson B, Leydon G, Rohrbaugh RM, Wilkins KM. Mental health self-care in medical students: a comprehensive look at help-seeking. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):37–46. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0202-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Güleç M, Bakir B, Ozer M, Uçar M, Kiliç S, Hasde M. Association between cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms among military medical students in Turkey. Psychiatry Res. 2005;134(3):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]