Through comparison of HEU and HUU children’s neurodevelopment, we examine the effect of in-utero HIV exposure on neurodevelopment among 24-month-old uninfected children.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

We sought to determine if HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) children had worse neurodevelopmental outcomes at 24 months compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) children in Botswana.

METHODS:

HIV-infected and uninfected mothers enrolled in a prospective observational study (“Tshipidi”) in Botswana from May 2010 to July 2012. Child neurodevelopment was assessed at 24 months with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III: cognitive, gross motor, fine motor, expressive language, and receptive language domains) and the Development Milestones Checklist (DMC), a caregiver-completed questionnaire (locomotor, fine motor, language and personal-social domains). We used linear regression models to estimate the association of in-utero HIV exposure with neurodevelopment, adjusting for socioeconomic and maternal health characteristics.

RESULTS:

We evaluated 670 children (313 HEU, 357 HUU) with ≥1 valid Bayley-III domain assessed and 723 children (337 HEU, 386 HUU) with a DMC. Among the 337 HEU children with either assessment, 122 (36%) were exposed in utero to maternal 3-drug antiretroviral treatment and 214 (64%) to zidovudine. Almost all HUU children (99.5%) breastfed, compared with only 9% of HEU children. No domain score was significantly lower among HEU children in adjusted analyses. Bayley-III cognitive and DMC personal-social domain scores were significantly higher in HEU children than in HUU children, but differences were small.

CONCLUSIONS:

HEU children performed equally well on neurodevelopmental assessments at 24 months of age compared with HUU children. Given the global expansion of the HEU population, results suggesting no adverse impact of in-utero HIV and antiretroviral exposure on early neurodevelopment are reassuring.

What’s Known on This Subject:

The effect of in-utero HIV exposure on the neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) children is uncertain. Previous studies have been limited by a lack of comparison with HIV-unexposed controls, small sample size, and inadequate assessment of potential confounders.

What This Study Adds:

We evaluated the association of in-utero HIV exposure with neurodevelopmental functioning among 337 HEU and 387 HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) 24-month-old children in Botswana. We found no differences in neurodevelopment between HEU and HUU children.

Approximately 1.5 million HIV-infected women globally deliver babies each year,1 with the vast majority of their HIV-exposed children now HIV-uninfected because of the successful expansion of programs to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission.1–5 The authors of studies investigating the effects of in-utero exposure to HIV and antiretrovirals (ARVs) on neurodevelopment in HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) children in Western settings have provided reassurance6–10 but have highlighted language delay associated with atazanavir.11,12 Although a growing number of studies have now been conducted in low-resource settings, the authors of previous studies in Africa have focused on neurodevelopment in children with HIV infection.13–15 Thus, the authors of studies in sub-Saharan Africa, where the burden of maternal HIV infection is highest, offer limited examination of HEU child neurodevelopment.14–19 African studies have been further limited by a lack of HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) controls who share similar key environmental characteristics to HEU children,16 by inclusion of only small numbers of HEU children (n = 35–136),17–19 or by lack of examination of confounders relevant to the neurodevelopment of HEU children in low-income settings.16–20

Differences observed in neurodevelopment between HEU and HUU children may be at least partially attributable to environmental and socioeconomic differences, rather than being solely attributable to the biological consequences of HIV exposure.16 This has been found to be particularly relevant in US settings, where HIV-infected women have historically had lower socioeconomic status and higher rates of substance use than the general population,9,11 potentially confounding the estimated effects of exposure to HIV on child neurodevelopment. The generalized HIV epidemic in Botswana allows better control of these potential confounders, as HIV affects all socioeconomic strata and maternal substance use is low.21 Additionally, children in Botswana are more likely to have similar exposure to potentially important environmental confounders of interest irrespective of their HIV-exposure status.16

To address these knowledge gaps, we compared neurodevelopmental outcomes between HEU and HUU children in Botswana.

Methods

The “Tshipidi” study is a prospective cohort study that enrolled HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected mothers between May 2010 and July 2012 at 2 sites in Botswana: Gaborone (the capital city) and Mochudi (a nearby village). Mothers aged ≥18 years were either pregnant (any gestational age) or recruited within 7 days of live-born delivery. All participants (regardless of HIV status) were recruited from local government health clinics at the time of routine antenatal care visits (or from maternity wards at the time of delivery, in a small number). Mothers and their infants were followed to evaluate effects of in-utero exposure to maternal HIV or to ARV drugs on neurodevelopment and child health outcomes at ∼24 months of age. HIV-infected mothers received either the ARV zidovudine (ZDV) prophylaxis or 3-drug ARV treatment (ART), in accordance with Botswana program guidelines. Most women with a cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) count >350 cells/mm3 received ZDV during pregnancy, and women with a CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3 or World Health Organization stage 3 or 4 HIV received ART. Combivir plus nevirapine (NVP) was the most commonly prescribed regimen (for just under two-thirds of the HIV-infected mothers who were receiving combination ART in this study). Less-frequently prescribed ARVs included atazanavir, NVP, tenofovir/emtricitabine, and lopinavir/ritonavir. HEU children received prophylaxis with a single dose of NVP and 1 month of ZDV. Infants were fed according to maternal choice in keeping with Botswana national program guidelines. HIV-infected mothers received infant feeding counseling in accordance with the Botswana HIV program guidelines during the period of the study (which promoted formula feeding with free infant formula provision for infants of HIV-infected mothers). The Botswana Health Research Development Committee and the Office of Human Research Administration at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health granted ethics approval, and all mothers provided written informed consent.

All women underwent HIV testing at enrollment (and HIV-infected women had CD4-count and HIV-1 RNA testing). Negative maternal HIV status was documented by negative rapid HIV test or licensed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Maternal HIV-1 infection was defined as positive rapid HIV or licensed ELISA test, followed by confirmation by 1 of these 2 tests: a Western blot test, or detectable HIV-1 RNA test. Discordant confirmatory results were followed by plasma HIV-1 RNA testing. Infant HIV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was performed in HEU children. A DNA PCR test with positive results was confirmed promptly with a second DNA PCR test or HIV-1 RNA to determine if a child was HIV-infected. All children underwent an 18-month HIV-1 ELISA (unless they were previously documented to be HIV-infected), regardless of maternal HIV status or feeding method.

Research nurses who were trained in questionnaire administration collected all maternal data via direct interview. We collected data on socioeconomic status, demographics, maternal health history (including ARV use for HIV-infected women), infant feeding method, and food insecurity.22 Questionnaire items included the Beck depression screen23 and social support24 scores, with higher scores reflecting worse depression and better social support, respectively. Additionally, a maternal substance use screen was used to capture use of tobacco and alcohol. Data on the primary child care provider were also collected via interview at 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of child age. Birth outcomes and complications and child health outcomes were collected via interview and child examination, in conjunction with review of medical records. Child height and weight were measured, and all children underwent HIV testing through the study. Questionnaire items and neurodevelopment instruments were translated into Setswana. Between the ages of 22 and 29 months, children completed 2 types of neurodevelopmental assessment. The first was the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III).25 Five raw domain scores were recorded for each child: cognitive, gross motor, fine motor, expressive language, and receptive language. The Bayley-III was adapted to be more culturally appropriate through focus groups, item modification, piloting, modifying, and repiloting. The second measure was the Development Milestones Checklist (DMC), developed for use within a sub-Saharan African context.26,27 The DMC is a parent report questionnaire with 4 domains: locomotor, fine motor, language and personal-social. This measure has been shown to have good internal consistency, with a test-retest reliability correlation coefficient of 0.85.26 Trained research nurses administered both the DMC and Bayley-II neurodevelopmental testing and recorded raw scores. Testing of both HEU and HUU children was performed in quiet study clinic rooms that had been prepared for this purpose. Neurodevelopmental assessors were observed during training until competency was confirmed. An invalid score was assigned to children who were unable to complete neurodevelopmental testing or whose scores did not appear to be an accurate reflection of ability, because of physical or behavioral problems suggestive of potential clinical impairment. Invalid scores were noted by clinical assessors and confirmed by the lead neuropsychologist (B.K.). Assessor performance was monitored periodically through video and/or direct observation by study coordinators and lead neuropsychologist (B.K.). Regular meetings were held to address any concerns raised during the quality control procedures for the assessments.

Linear regression models were used to compare 24-month neurodevelopmental outcomes between HEU and HUU children, both unadjusted and adjusted for confounders. Raw Bayley-III scores were assessed and a similar age distribution noted among HEU and HUU children. A separate model was fit for each of the 5 Bayley-III and 4 DMC neurodevelopmental domain scores. Unadjusted and adjusted mean Bayley-III and DMC domain scores were assessed by HIV exposure status, along with differences in means (with corresponding confidence intervals) between HEU and HUU children. Standardized effect sizes for mean differences are also reported by using Cohen’s d.28 Children with invalid scores for specific neurodevelopmental domains were excluded from primary analyses for that outcome but were included in any analyses of outcomes for which they had valid scores.

Potential confounders were selected by using a priori knowledge and directed acyclic graphs to delineate assumptions regarding the causal pathway of interest.

Multiple socioeconomic (maternal age, education, and income), environmental (electricity, housing, water, access to sanitation, and study site), and maternal mental health characteristics (depression, alcohol, and tobacco use during pregnancy) were evaluated as potential confounders of the association of interest. Among these potential confounders, all child and maternal characteristics with unadjusted P values < .20 for association with a specific neurodevelopmental domain score were included in adjusted models. Covariates with P values > .20 in multivariable models were subsequently excluded.

Low birth weight (<2500 g) and preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation) have previously been associated with both in-utero ARV exposure and impaired infant neurodevelopment.29–31 Hence, neither low birth weight nor preterm delivery was considered within primary analyses because they were deemed to be possible mediators on the causal pathway between ARV exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Sensitivity analyses to examine these potential mediators were performed by including the suspect variable within adjusted models to look for changes in the specific domain effect estimate.

Further analyses were conducted by using logistic regression to compare HEU with HUU children for occurrence of a dichotomous “adverse neurodevelopmental outcome” defined as the presence of either a low score (<1 SD below the Bayley-III domain-specific mean) or an invalid score. Other demographic and home environment predictors of an adverse neurodevelopment outcome in each domain were also explored.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Enrollment, Neurodevelopmental Assessment Completeness, and Baseline Characteristics

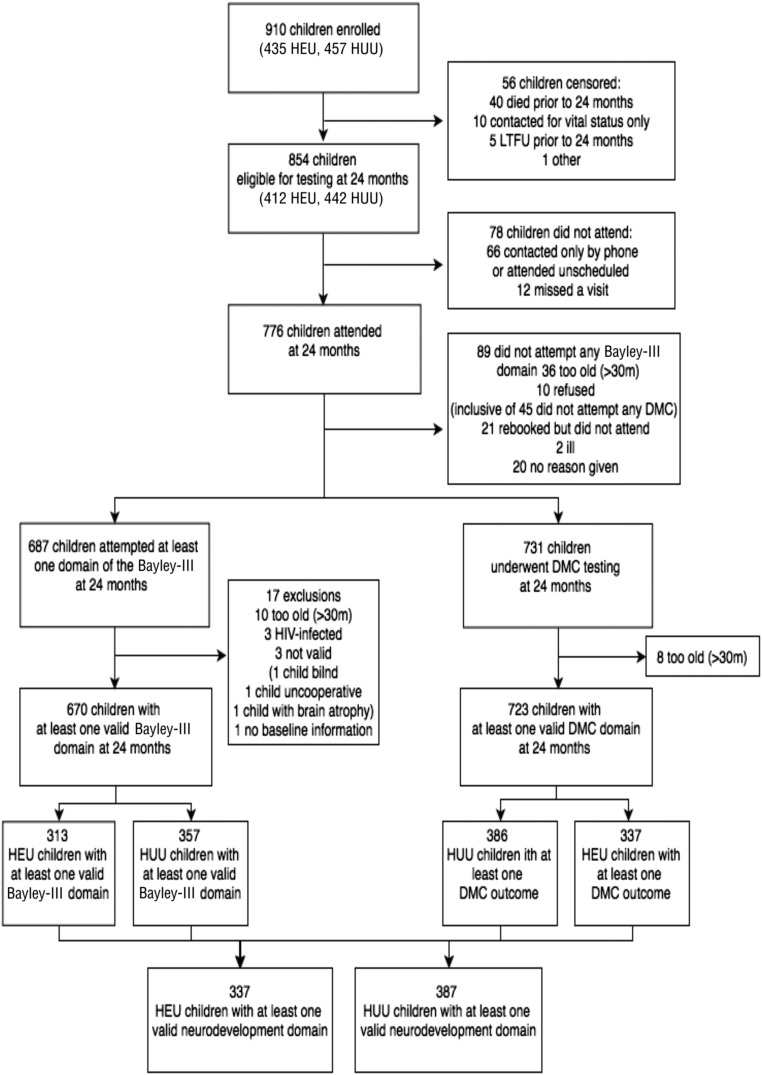

A total of 949 eligible mothers enrolled; 1 died before delivery, 15 moved out of the study area, and 21 refused further contact. Thus, 912 women (454 HIV-infected, 458 HIV-uninfected) were followed, and delivered 910 live-born infants (453 HEU and 457 HUU infants, Fig 1). Vital status at 24 months was ascertained for 905 (99.5%) of children; 412 (90%) of the HEU children and 422 (92%) of the HUU children attended a 24-month study visit. Among those attending a 24-month visit, 313 HEU children (76%) and 357 HUU children (85%) completed at least 1 valid Bayley-III domain score, and 337 HEU children (82%) and 386 HUU children (92%) had a caregiver-completed DMC. Of the mothers who were on ART during pregnancy, 48% started before conception, whereas 52% started during pregnancy. The median duration of ART was 9.5 months (interquartile range: 3–48), and the median duration of ZDV was 2.5 months (interquartile range: 2–2.9).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of HEU and HUU infants undergoing neurodevelopment assessment. LTFU, loss to follow-up.

Among children with at least 1 valid Bayley-III domain score, those missing 1 or more other domain scores did not differ according to their baseline characteristics (compared with children not missing any assessed domains), with the exception of children born preterm (Supplemental Table 5): preterm infants were significantly more likely to have missing Bayley-III assessments. Among children eligible for neurodevelopmental testing but not tested (Supplemental Table 6), higher percentages of children were exposed to HIV (67% vs 46%), formula fed (57% vs 35%), of low birth weight (<2500 g, 22% vs 13%), and born preterm (gestational age <37 weeks, 22% vs 13%), compared with children who were tested.

Maternal and infant clinical and sociodemographic characteristics according to maternal HIV exposure status (among children with at least 1 valid neurodevelopmental domain score) are presented in Table 1. Although only 9% of HEU children were ever breastfed, nearly all HUU children were breastfed. A greater proportion of HEU children were born with low birth weight compared with HUU children (17% vs 9%). HIV-infected women were generally older than HIV-uninfected women, with more than half being over the age of 25 at delivery (53% vs 26%, respectively). Approximately one-third of the HIV-infected mothers took 3-drug ART during pregnancy (n = 122, 36%) and 214 (64%) took ZDV monotherapy (ARV regimens are summarized in Table 1). HIV-infected mothers reported lower levels of education and had less access to electricity and water within their households and greater food insecurity than HIV-uninfected mothers (although higher proportions of HIV-infected women reported working and having some personal earnings). HIV-infected mothers scored worse on the depression screen but reported similar levels of social support compared with HIV-uninfected mothers. Maternal self-report of illicit substance use was low (<1%); 6% reported ever having used alcohol, with a slightly higher proportion among HIV-infected women. The most common primary caregivers were the infant’s mother or father, followed by the infant’s grandparents (with increasing frequency of care by grandparents or other individuals with increasing child age). The type of primary caregiver was similar among HEU versus HUU children (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Mothers and Their Uninfected Children According to HIV Exposure in the Tshipidi Study, Botswana, 2010–2012

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 724), N (%) | HIV-Infected Mothers/HIV-Exposed Children (N = 337), N (%) | HIV-Uninfected Mothers/HIV-Unexposed Children (N = 387), N (%) | P (χ2 or t test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfed | 415 (57.3%) | 30 (8.9%) | 385 (99.5%) | <.01 |

| Female | 367 (50.7%) | 168 (49.9%) | 199 (51.4%) | .67 |

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 89 (12.8%) | 46 (13.9%) | 43 (11.7%) | .37 |

| Low birth weight | 92 (12.8%) | 58 (17.2%) | 34 (8.9%) | <.01 |

| 3-drug ART | 122 (16.9%) | 122 (36.2%) | — | — |

| CBV + NVP | 68 (9.4%) | 68 (20.2%) | — | — |

| NVP + TRV | 11 (1.5%) | 11 (3.3%) | — | — |

| ATR | 10 (1.4%) | 10 (3.0%) | — | — |

| ALU + CBV | 9 (1.2%) | 9 (2.7%) | — | — |

| Other | 24 (3.3%) | 24 (7.1%) | — | — |

| ZDV monotherapy | 214 (29.6%) | 214 (63.5%) | — | — |

| No ARVs | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | — | — |

| Mean CD4 cells/mm3 (SD) | — | 449 (190) | — | — |

| Mean log viral copies/mL (SD) | — | 4.2 (2.6) | — | — |

| Site of enrollment | — | — | — | <.01 |

| Gaborone | 369 (51.0%) | 203 (60.2%) | 166 (42.9%) | — |

| Mochudi | 355 (49.0%) | 134 (39.8%) | 221 (57.1%) | — |

| Mean maternal age (SD) | 27.2 (6.1) | 28.9 (5.8) | 25.7 (6.0) | <.01 |

| Education | ||||

| None | 10 (1.4%) | 7 (2.1%) | 3 (0.8%) | <.01 |

| Primary | 60 (8.3%) | 43 (12.8%) | 17 (4.4%) | — |

| Secondary junior | 362 (50.1%) | 204 (60.7%) | 158 (40.9%) | — |

| >Secondary junior | 290 (40.2%) | 82 (24.4%) | 208 (53.9%) | — |

| Maternal income | ||||

| None | 466 (64.5%) | 187 (55.8%) | 279 (72.1%) | <.01 |

| <P500 | 37 (5.1%) | 26 (7.8%) | 11 (2.8%) | — |

| P501–P1000 | 96 (13.3%) | 65 (19.4%) | 31 (8.0%) | — |

| >P1000 | 123 (17.0%) | 57 (17.0%) | 66 (17.1%) | — |

| Access to sanitation | ||||

| Indoor | 155 (21.6%) | 57 (17.0%) | 98 (25.6%) | <.01 |

| Private | 481 (66.9%) | 229 (68.2%) | 252 (65.8%) | — |

| Shared | 83 (11.5%) | 50 (14.8%) | 33 (8.6%) | — |

| Electricity in home | 412 (57.0%) | 164 (48.8%) | 248 (64.1%) | <.01 |

| Access to water | ||||

| Home | 143 (19.8%) | 55 (16.4%) | 88 (22.7%) | <.01 |

| Yard | 495 (68.5%) | 226 (67.3%) | 269 (69.5%) | — |

| Communal | 74 (10.2%) | 48 (14.3%) | 26 (6.7%) | — |

| Other | 11 (1.5%) | 7 (2.1%) | 4 (2.1%) | — |

| Main cooking method | ||||

| Gas, electric | 525 (72.6%) | 240 (71.4%) | 285 (73.6%) | .12 |

| Wood | 181 (25.0%) | 84 (25.0%) | 97 (25.1%) | — |

| Kerosene | 8 (1.1%) | 7 (2.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | — |

| None | 9 (1.2%) | 5 (1.5%) | 4 (1.0%) | — |

| Housing type | ||||

| Formal | 715 (98.9%) | 331 (98.5%) | 384 (99.2%) | .61 |

| Informal | 6 (0.8%) | 4 (1.2%) | 2 (0.5%) | — |

| None | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | — |

| Food insecurity mean (SD) | — | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.1) | — |

| None | 252 (34.9%) | 95 (28.2%) | 157 (40.7%) | <.01 |

| Mild | 164 (22.7%) | 63 (18.7%) | 101 (26.2%) | — |

| Moderate | 176 (24.3%) | 97 (28.8%) | 79 (20.5%) | — |

| Severe | 131 (18.1%) | 82 (24.3%) | 49 (12.7%) | — |

| Depression mean score (0–20) (SD)a | 2.5 (2.7) | 2.8 (2.8) | 2.1 (2.6) | <.01 |

| Social support mean score (0–40) (SD)b | 33.9 (6.0) | 34.4 (6.0) | 33.5 (6.0) | .05 |

| Alcohol use (ever) | 46 (6.4%) | 24 (7.1%) | 22 (5.7%) | <.01 |

| Tobacco use (ever) | 10 (1.4%) | 5 (1.5%) | 5 (1.3%) | .25 |

Percentage of participants missing values for variables: preterm: 3.6%, low birth weight: 0.7%, maternal education: 0.1%, maternal income: 0.3%, sanitation: 0.7%, electricity in home: 0.1%, source of water: 0.1%, cooking method: 0.1%, housing: 0.1%, food insecurity22: 0.1%, depression: 0%, social support: 5.5%, alcohol use (ever): 55.6%, tobacco use (ever): 58.8%. ATR, Atripla, ALU, Aluvia; CBV, Combivir; P, pula; TRV, Truvada; —, not applicable.

Highest score for a given mother on the Beck Depression Score,23 from antepartum and postpartum assessments (high scores indicating worse depression).

Highest score for a given mother’s assessment of her social support24 (high scores indicating better social support).

Bayley-III Outcomes

Each neurodevelopmental domain was found to be significantly associated with at least 1 previously described maternal socioeconomic or environmental predictor of worse neurodevelopment in univariable linear regression models (Supplemental Tables 7 and 8). For example, increasing maternal age, income, and educational levels were associated with higher Bayley-III scores in several domains (as was breastfeeding). Lower-quality housing; worse food insecurity; and maternal depression, higher stigma, low social support, and alcohol use were each associated with lower Bayley-III score in at least 1 domain.

HEU children had lower unadjusted and adjusted Bayley-III expressive language scores than HUU children (adjusted mean difference = −0.58, P = .09). Bayley-III unadjusted and adjusted receptive language and DMC language scores were no different in HEU versus HUU children. HEU children had higher unadjusted and adjusted scores in Bayley-III cognitive (adjusted mean difference = 0.59, P = .03) and DMC personal-social domains (adjusted mean difference = 0.71, P = .03) than HUU children (Tables 2 through 4). No further significant differences were identified between HEU and HUU children across all other Bayley-III and DMC domains. Sensitivity analyses further incorporating potential mediators (birth weight and preterm delivery) into multivariable models resulted in no substantial changes in differences between HEU and HUU children in adjusted Bayley-III and DMC domain effect estimates (Supplemental Table 9).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Mean and Adjusted Bayley-III and DMC Neurodevelopment Domain Scores According to HIV Exposure in the Tshipidi Study, Botswana, 2010–2012

| Bayley-III Domain | N | Mean (SD) | Unadjusted Difference | Adjusted Difference | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEU | HUU | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Estimate (95% CI) | P | Cohen’s D (95% CI) | ||

| Cognitive | 657 | 53.8 (3.4) | 53.0 (3.3) | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.2) | <.01 | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1) | .03 | 0.22 (−0.04 to 0.47) |

| Gross motor | 642 | 52.6 (2.8) | 52.9 (2.7) | −0.3 (−0.7 to 0.2) | .21 | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.3) | .63 | −0.10 (−0.31 to 0.11) |

| Fine motor | 668 | 37.3 (1.8) | 37.4 (1.8) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | .47 | 0.0 (−0.3 to 0.3) | .98 | −0.06 (−0.19 to 0.08) |

| Expressive language | 652 | 25.0 (4.4) | 25.8 (4.1) | −0.8 (−1.4 to −0.2) | .02 | −0.6 (−1.3 to 0.1) | .09 | −0.19 (−0.51 to 0.13) |

| Receptive language | 652 | 21.1 (3.5) | 20.7 (3.3) | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.9) | .21 | 0.3 (−0.3 to 0.8) | .35 | 0.10 (−0.16 to 0.36) |

| DMC domain | ||||||||

| Locomotor | 723 | 32.2 (1.8) | 32.2 (1.8) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) | .58 | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.2) | .66 | −0.04 (−0.18 to 0.09) |

| Fine motor | 718 | 19.1 (2.3) | 19.4 (1.9) | −0.3 (−0.6 to 0.0) | .05 | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) | .63 | −0.15 (−0.30 to 0.01) |

| Language | 723 | 16.5 (2.6) | 16.5 (2.7) | 0.0 (−0.4 to 0.4) | .92 | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.6) | .43 | −0.01 (−0.20 to 0.19) |

| Personal-social | 720 | 45.1 (3.9) | 44.5 (4.5) | 0.6 (0.0 to 1.2) | .06 | 0.7 (0.1 to 1.3) | .02 | 0.14 (−0.17 to 0.45) |

Bayley-III: cognitive adjusted for maternal income and depression; gross motor adjusted for household access to water and food insecurity; fine motor adjusted for access to sanitation, maternal education, and housing type; expressive language adjusted for maternal education and household access to electricity; receptive language adjusted for maternal age. DMC: locomotor adjusted for maternal income and depression, fine motor adjusted for maternal education and social score, language adjusted for maternal education and maternal depression, personal-social adjusted for cooking method and maternal depression. CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 4.

Adjusted Mean Differences in DMC Neurodevelopment Scores According to Significant Predictors in the Tshipidi Study, Botswana, 2010–2012

| Covariate | DMC Neurodevelopment Domains Estimates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locomotor Estimate (SE) | P | Fine Motor Estimate (SE) | P | Language Estimate (SE) | P | Personal-Social Estimate (SE) | P | |

| In-utero exposure to HIV | — | — | — | 0.74 (0.32) | .02 | |||

| Maternal | ||||||||

| Income | 0.12 (0.06) | .04 | — | — | — | |||

| Depression | −0.08 (0.03) | <.01 | — | −0.06 (0.04) | .10 | −0.11 (0.06) | .08 | |

| Education | — | 0.46 (0.12) | <.01 | 0.35 (0.15) | .02 | — | ||

| Social score | — | 0.02 (0.01) | .06 | — | — | |||

| Household | ||||||||

| Cooking method (gas or electric vs wood burning) | — | — | — | 0.69 (0.37) | .06 | |||

| Cooking method (kerosene vs wood burning) | — | — | — | −2.76 (1.55) | .08 | |||

| Cooking method (none vs wood-burning) | — | — | — | 1.01 (1.44) | .48 | |||

| Preterm (<37 wk)a | −0.50 (0.21) | .02 | −0.41 (0.24) | .09 | −0.28 (0.31) | .35 | −0.63 (0.49) | .19 |

| Low birth weighta | −0.40 (0.21) | .05 | −0.05 (0.24) | .84 | −0.39 (0.30) | .19 | −0.13 (0.48) | .78 |

Bivariate associations for these covariates are shown in models fitted with the main exposure of interest (in-utero exposure to HIV) in the Tshipidi study, Botswana, 2010–2012. —, not applicable.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted Mean Differences in Bayley-III Scores According to Significant Predictors in the Tshipidi Study, Botswana, 2010–2012

| Covariate | Bayley-III Neurodevelopment Domain Estimates | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Estimate (SE) | P | Gross Motor Estimate (SE) | P | Fine Motor Estimate (SE) | P | Expressive Language Estimate (SE) | P | Receptive Language Estimate (SE) | P | |

| In-utero exposure to HIV | 0.59 (0.26) | .03 | — | — | −0.58 (0.35) | .09 | — | |||

| Maternal factors | ||||||||||

| Older age | — | — | — | — | 0.14 (0.11) | .20 | ||||

| Depression | 0.09 (0.05) | .07 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Socioeconomic factors | ||||||||||

| Higher education | — | — | 0.18 (0.11) | .10 | 0.77 (0.26) | <.01 | — | |||

| Higher income | 0.33 (0.11) | <.01 | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Less access to water | — | −0.30 (0.10) | <.01 | — | — | — | ||||

| Food insecurity | — | −0.18 (0.10) | .06 | — | — | — | ||||

| Less access to sanitation | — | — | −0.28 (0.13) | .02 | — | — | ||||

| Lower quality housing | — | — | −0.89 (0.48) | .06 | — | — | ||||

| Access to electricity | — | — | — | 0.58 (0.34) | .09 | — | ||||

| Preterm (<37 wk)a | −0.64 (0.41) | .12 | −0.91 (0.33) | <.01 | −0.37 (0.22) | .09 | −0.06 (0.52) | .90 | −0.82 (0.42) | .05 |

| Low birth weighta | −1.24 (0.39) | <.01 | −1.19 (0.33) | <.01 | −0.31 (0.21) | .15 | −0.94 (0.50) | .06 | −0.63 (0.40) | .12 |

Bivariate associations for these covariates are shown in models fitted with the main exposure of interest (in-utero exposure to HIV). —, not applicable.

Predictors of Composite Adverse Neurodevelopmental Outcome

When evaluating the dichotomous measure of an adverse neurodevelopmental outcome (low score or invalid test), we observed few differences by HIV exposure status. However, HEU children were more likely to have an adverse expressive language outcome than HUU (53% vs 44%, Supplemental Tables 10 and 11), which persisted after adjustment for confounders (adjusted odds ratio 1.44 [95% confidence interval: 1.01 to 2.06], Supplemental Table 12). We also observed a higher risk of adverse cognitive outcomes for children born to younger mothers or residing in low-income households. Low birth weight and preterm birth were fairly consistently associated with adverse outcomes across all 5 Bayley-III domains.

Discussion

We found no clinically important differences in neurodevelopment at 24 months of age among children exposed to HIV in utero, with small effect sizes observed (ranging from −0.19 to +0.22). The HEU group scored lower then HUU group in expressive language, as did the HEU adverse outcome group, and the HEU group scored higher in the cognitive domain on the Bayley-III and personal-social scales. However, the effect sizes are small and unlikely to be of clinical significance. Our overall findings provide reassurance that in-utero HIV exposure (and associated ARV exposures) does not adversely affect neurodevelopment in young children in Botswana.

We explored potential environmental and socioeconomic confounders of relevance. Many of the domain-specific predictors we identified have been described previously, although a number are highlighted here for the first time. For instance, it has been well described previously that maternal education, age, and income are associated with Bayley-III cognitive and language neurodevelopmental domains, as was further confirmed in our study.6–11,16–18 In our study, we highlight the potential importance of maternal depression in influencing a number of domain-specific neurodevelopment outcomes, such as Bayley-III cognitive and DMC locomotor, language, and personal-social scores. Various socioeconomic factors, such as access to food, housing, water, sanitation and electricity, and cooking method within the household, were found to be associated with a number of outcomes across adjusted domain-specific models. Approximately 6% of the mothers in this Botswana study sample reported alcohol use, although this may have been underreported because of social-desirability bias. Maternal alcohol use was significantly associated with worse scores in both Bayley-III cognitive and expressive language domains in univariable linear regression but was not significant in any of the adjusted models.

The strengths of our study included its prospective nature, its large sample size, and our ability to test and control for a large number of previously unexplored potential environmental and socioeconomic confounders. Additionally, the context of investigation within a large generalized HIV epidemic (in which HIV-infected and uninfected mothers were similar in many key ways) facilitated assessment of the specific effect of HIV exposure on neurodevelopment (with less unmeasured confounding). The large sample size provided 80% power to detect small but clinically significant differences (0.18 SDs) in mean neurodevelopmental scores between HEU and HUU children. Although a multitude of studies have included examinations of neurodevelopment among HIV-infected children14,15 by using HEU children only as controls,15 our study is one of few studies to date in which neurodevelopment in HEU and HUU children in sub-Saharan Africa were compared.16–19 Kandawasvika et al16 enrolled 188 HEU children and 287 HUU children, but did not present a comparison of their neurodevelopmental outcomes. Msellati et al17 followed 91 HEU and 84 HUU children to 24 months of age and did not find any differences in their neurodevelopmental outcomes, following both groups largely to serve as controls for HIV-infected children. In this study, we are the first to offer adequate assessment of many potential confounders relevant to this setting, as previous efforts have provided unadjusted comparisons of HEU versus HUU child neurodevelopment only.17–19 Van Rie et al19 compared 19 HEU children with 31 HUU children in the Democratic Republic of Congo and found a possible expressive language delay among HEU children when compared with HUU children, although overall sample size was too small to control for potential confounders. HEU and HUU children within their study differed significantly across a range of socioeconomic factors with inadequate opportunity to control for these differences.19 With our findings, we further confirm the importance of socioeconomic and environmental influences on child neurodevelopment in sub-Saharan settings, underscoring the importance of adjusted comparisons of HEU versus HUU children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes.

With these findings, we also confirm the likely safety of in-utero exposures to maternal HIV and associated ARVs with respect to early child development.6,7,9–11,17–19 Atazanavir has been implicated in possible language domain deficits in a number of studies in North America.7,12,31 Only a small number of women were taking atazanavir-containing regimens during pregnancy in our study; hence, we did not have sufficient power to assess for expressive language deficits among our atazanavir exposed children.

A major limitation of our study was our inability to adjust for the effect of breastfeeding because 99.5% of the HUU children were breastfed. Breastfeeding is a well-established determinant of improved neurodevelopment.31–34 Despite this, the largely breastfed HUU children in this study did not have higher neurodevelopmental outcomes across all domains than formula-fed HEU children. Current World Health Organization guidelines support exclusive breastfeeding by mothers in resource-limited settings who are taking virologically suppressive ARVs.35 Another limitation is the difference in some baseline characteristics between children who were tested versus those not tested. Sensitivity analyses identified that variables that were imbalanced between comparison groups, such as low birth weight and preterm delivery, did not impact Bayley-III and DMC domain effect estimates. Most baseline covariates (other than feeding method) were evenly distributed between HEU and HUU groups, and differences were accounted for in adjusted estimates. Differences in HEU and HUU neurodevelopmental functioning may be subtle in early life, and microstructural alterations have been described.36 Further differences may emerge with age; hence, our findings may not be applicable to older children, nor to HEU children exposed in utero to other ARV regimens.

Conclusions

Our findings provide reassurance that in-utero exposure to HIV and associated ARVs does not significantly adversely affect neurodevelopment in young children.

Glossary

- ART

antiretroviral treatment

- ARV

antiretroviral

- Bayley-III

Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition

- CD4

cluster of differentiation 4

- DMC

Development Milestones Checklist

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HEU

HIV-exposed uninfected

- HUU

HIV-unexposed uninfected

- NVP

nevirapine

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ZDV

zidovudine

Footnotes

Dr Chaudhury conducted the analysis and interpretation of study data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Mayondi, Sakoi, Magetse, Mdluli, and Moabi and Mr Makhema and Jibril contributed significantly to acquisition of study data; Drs Holding, Nichols, and Tepper provided expertise for the design and use of neurodevelopment assessments; Dr Williams was the senior statistician and coinvestigator of the Tshipidi study and contributed to study conception and design; Ms Leidner was a statistician and analyst for the Tshipidi study and Dr Seage provided expertise in epidemiologic methods; Drs Lockman and Kammerer were coprincipal investigators of the Tshipidi study, designed and conceived the study, and oversaw all aspects of the study; and all authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: The Tshipidi study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (RO1MH087344) and by the Oak Foundation. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS ; Global Update on HIV Treatment 2013: Results, Impact and Opportunities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Doaré K, Bland R, Newell ML. Neurodevelopment in children born to HIV-infected mothers by infection and treatment status. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/130/5/e1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filteau S. The HIV-exposed, uninfected African child. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(3):276–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landes M, van Lettow M, Chan AK, Mayuni I, Schouten EJ, Bedell RA. Mortality and health outcomes of HIV-exposed and unexposed children in a PMTCT cohort in Malawi. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugandhi N, Rodrigues J, Kim M, et al. HIV-exposed infants: rethinking care for a lifelong condition. AIDS. 2013;27(suppl 2):S187–S195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams PL, Marino M, Malee K, Brogly S, Hughes MD, Mofenson LM; PACTG 219C Team . Neurodevelopment and in utero antiretroviral exposure of HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/125/2/e250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozyce ML, Huo Y, Williams PL, et al. ; Pediatric HIVAIDS Cohort Study . Safety of in utero and neonatal antiretroviral exposure: cognitive and academic outcomes in HIV-exposed, uninfected children 5-13 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(11):1128–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindsey JC, Malee KM, Brouwers P, Hughes MD; PACTG 219C Study Team . Neurodevelopmental functioning in HIV-infected infants and young children before and after the introduction of protease inhibitor-based highly active antiretroviral therapy. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/3/e681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alimenti A, Forbes JC, Oberlander TF, et al. A prospective controlled study of neurodevelopment in HIV-uninfected children exposed to combination antiretroviral drugs in pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/4/e1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase C, Ware J, Hittelman J, et al. ; Women and Infants Transmission Study Group . Early cognitive and motor development among infants born to women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/106/2/e25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirois PA, Huo Y, Williams PL, et al. ; Pediatric HIVAIDS Cohort Study . Safety of perinatal exposure to antiretroviral medications: developmental outcomes in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(6):648–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice ML, Zeldow B, Siberry GK, et al. ; Pediatric HIVAIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) . Evaluation of risk for late language emergence after in utero antiretroviral drug exposure in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(10):e406–e413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abubakar A, Van Baar A, Van de Vijver FJ, Holding P, Newton CR. Paediatric HIV and neurodevelopment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(7):880–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Rie A, Dow A, Mupuala A, Stewart P.. Neurodevelopmental trajectory of HIV-infected children accessing care in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(5):636–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drotar D, Olness K, Wiznitzer M, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of Ugandan infants with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Pediatrics. 1997;100(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/100/1/e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandawasvika GQ, Ogundipe E, Gumbo FZ, Kurewa EN, Mapingure MP, Stray-Pedersen B. Neurodevelopmental impairment among infants born to mothers infected with human immunodeficiency virus and uninfected mothers from three peri-urban primary care clinics in Harare, Zimbabwe. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(11):1046–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Msellati P, Lepage P, Hitimana DG, Van Goethem C, Van de Perre P, Dabis F. Neurodevelopmental testing of children born to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seropositive and seronegative mothers: a prospective cohort study in Kigali, Rwanda. Pediatrics. 1993;92(6):843–848 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boivin MJ, Green SD, Davies AG, Giordani B, Mokili JK, Cutting WA. A preliminary evaluation of the cognitive and motor effects of pediatric HIV infection in Zairian children. Health Psychol. 1995;14(1):13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Rie A, Mupuala A, Dow A. Impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the neurodevelopment of preschool-aged children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/1/e123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puthanakit T, Ananworanich J, Vonthanak S, et al. ; PREDICT Study Group . Cognitive function and neurodevelopmental outcomes in HIV-infected children older than 1 year of age randomized to early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy: the PREDICT neurodevelopmental study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(5):501–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National AIDS Coordinating Agency (NACA) Botswana 2013 global AIDS response report. 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/file,94425,es..pdf. Accessed May 1, 2016

- 22.Jennifer CJ, Swindale A, Bilinsky P Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household good access: indicator guide, version 3. 2007. Available at: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/HFIAS_ENG_v3_Aug07.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2017

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI: Fast Screen for Medical Patients Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26(7):709–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. Technical Manual. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abubakar A, Holding P, Van de Vijver F, Bomu G, Van Baar A. Developmental monitoring using caregiver reports in a resource-limited setting: the case of Kilifi, Kenya. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(2):291–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prado EL, Abubakar AA, Abbeddou S, Jimenez EY, Some JW, Ouedraogo JB. Extending the developmental milestones checklist for use in a different context in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(4):447–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vohr BR, Wright LL, Poole WK, McDonald SA. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants <32 weeks’ gestation between 1993 and 1998. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blencowe H, Lee AC, Cousens S, et al. Preterm birth-associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(suppl 1):S17–S34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caniglia EC, Patel K, Huo Y, et al. ; Pediatric HIVAIDS Cohort Study . Atazanavir exposure in utero and neurodevelopment in infants: a comparative safety study. AIDS. 2016;30(8):1267–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dee DL, Li R, Lee L-C, Grummer-Strawn LM. Associations between breastfeeding practices and young children’s language and motor skill development. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1 suppl 1):S92–S98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCrory C, Murray A. The effect of breastfeeding on neuro-development in infancy. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(9):1680–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sacker A, Quigley MA, Kelly YJ. Breastfeeding and developmental delay: findings from the millennium cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/3/e682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, et al. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2282–2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran LT, Roos A, Fouche JP, et al. White matter microstructural integrity and neurobehavioral outcome of HIV-exposed uninfected neonates. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(4):e2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.