Abstract

Clostridium difficile has become a common healthcare-associated infection over the past few years and gained more attention. C. difficile was estimated to cause almost half a million infections in USA in 2011 and 29 000 died within 30 days of the initial diagnosis. Although colitis due to C. difficile is the most common presentation, there have been reported cases of extraintestinal infections. As per our review of literature, this is the third reported case of liver abscess due to the organism.

Keywords: hepatitis and other GI infections, nosocomial infections

Background

Clostridium difficile incidence is gradually increasing over the past few years and several measures are taken by hospitals to prevent the infection due high disease related morbidity and mortality as reported by Fernanda et al.1 This case reflects a need to take the infection even more seriously due to its ability to form abscesses and cause other extraintestinal infections.2–4 Extraintestinal C. difficile has a very high mortality rate. There have also been reported cases of bacteraemia due to the infection. We present a case of liver and pancreatic abscesses due to C. difficile. This case report also includes a brief discussion on the prior reported cases of extraintestinal C. difficile infection.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old man was admitted to an outlying hospital after he presented with acute abdominal pain associated with nausea and vomiting. His medical history was significant for hypothyroidism, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and hypertension. On admission, the patient was noted to have elevated lipase of 6800 units/L. There was no history of cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy. Social history was non-significant with no reported alcohol abuse, smoking or illicit drug use. Patient reported no prior episodes of pancreatitis. The patient denied any diarrhoea and bloody stool prior to the admission. He was noted to have persistent fever on admission. A CT of the abdomen was obtained that showed findings consistent with acute pancreatitis without necrosis (figure 1). He had a drop in haemoglobin and was transferred to our facility with concerns of acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis. The patient also had worsening abdominal pain associated with it. Repeat imaging was performed that showed findings consistent with necrotising pancreatitis with no concerns for haemorrhagic pancreatitis and he was started on piperacillin-tazobactam (figure 2). By day 5 of hospitalisation, the patient developed watery diarrhoea. Stool PCR testing was done and resulted positive. Real time stool PCR testing against toxin B producing gene tcdB is a sensitive and specific test now used in USA for detecting C. difficile toxin production.4 The test has the advantage of being available within 1 hour. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for first episode of C. difficile colitis. With no improvement in symptoms and worsening diarrhoea over the next few days, antibiotic coverage for C. difficile infection was switched to oral vancomycin 250 mg four times a day. Diarrhoea gradually improved and the patient was discharged to inpatient rehabilitation with subsequent discharge back home.

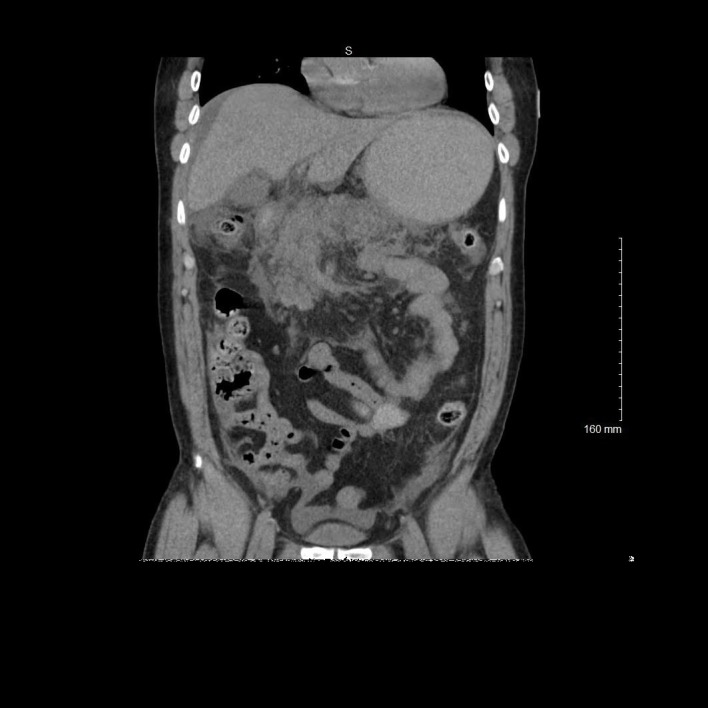

Figure 1.

Coronal view of contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating inflammatory changes of the pancreas consistent with acute pancreatitis.

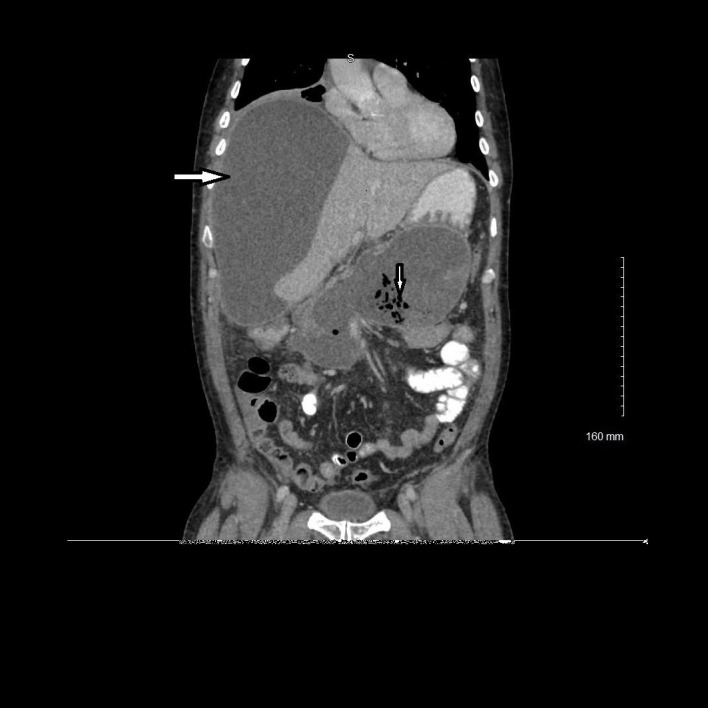

Figure 2.

Coronal view of contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating development of necrotising pancreatitis (left arrow).

The patient had other complications related to severe pancreatitis during his hospital stay, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome, bilateral pleural effusions, pseudocyst formation and acute splenic vein thrombosis. He was started on coumadin for splenic vein thrombosis prior to discharge. The plan on discharge was to repeat CT of the abdomen in 1 month with possible drainage of pseudocyst if needed.

The patient returned to the emergency room within a week of discharge with fever and chills. His chief complaint was severe right-sided back pain. Stool PCR testing does not differentiate between active toxin production and asymptomatic carriers and therefore is recommended for testing in patients with more than three loose stools over 24 hours duration. As during this admission, our patient did not report loose stool, a repeat stool PCR testing was not done. He denied any shortness of breath or productive cough. A repeat CT of the abdomen was done that showed fluid and air collection within the pancreas consistent with an infected pseudocyst, a large low-density subcapsular hepatic fluid collection (figure 3). The patient was again admitted in the intensive care unit (ICU) with hypotension on admission. He was started on meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for empirical treatment of intra-abdominal infection. Interventional Radiology Service was consulted, and percutaneous drains were placed into both fluid collections, with drainage of brown opaque fluid. He continued to have worsening abdominal distension while admitted in the ICU and repeat third CT of the abdomen was done that showed extraluminal, loculated large fluid and gas collection within the ventral abdomen, concerning for hollow viscus perforation (figure 4). Surgery was consulted. The patient was taken for emergent exploratory laparotomy and was found to have generalised peritonitis with noted stool in the peritoneal cavity, originating from perforated sigmoid colon near the rectal margin. He underwent partial colectomy followed by diverting colostomy.

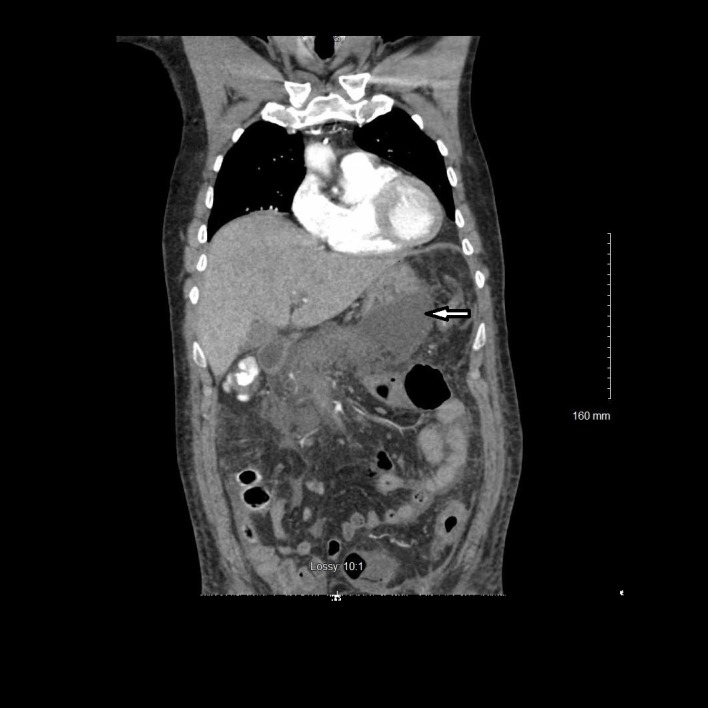

Figure 3.

Coronal view of contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating fluid and air collection in the pancreatic region consistent with infected pseudocyst (down arrow) and low-density subcapsular hepatic fluid collection consistent with hepatic abscess (right arrow).

Figure 4.

Coronal view of contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating extraluminal loculated large fluid and gas collection within the ventral abdomen consistent with hollow viscus perforation.

Anaerobic fluid culture from the liver abscess drainage and the pancreatic drainage grew heavy C. difficile and Candida glabrata on day 5. C. difficile bacteria were grown on selective agar media containing cycloserine-cefoxitin and was incubated in anaerobic jars at 35°C. Two sets of blood cultures on admission remained negative.

Polymicrobial growth from abscesses in the setting of acute sigmoid rupture pointed towards need for antimicrobial coverage against known pathogens as well as other usual intra-abdominal pathogens. Intravenous metronidazole at 500 mg every 6 hours was added to meropenem 1 g intravenously every 8 hours for empirical coverage of intra-abdominal organisms. Intravenous vancomycin 1250 mg every 12 hours was started for additional intra-abdominal coverage and potential benefit with regard to extraluminal C. difficile infection. Intravenous micafungin 100 mg every 24 hours was started to cover for Candida infection. Intravenous vancomycin was switched to per oral vancomycin once the patient had a functional colostomy and able to take oral medications. Repeat body fluid cultures were negative for gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotic coverage was switched to intravenous micafungin and oral flagyl for total 8 weeks of empirical treatment.

Our patient had a prolonged hospital stay with several drains and lavages done. Due to multiple interventions, his hospital stay was further complicated after his pancreatic drain was lavaged and the patient developed gastroduodenal artery rupture controlled with acute embolisation.

Treatment

The patient was started initially on meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for empirical treatment intra-abdominal infection. On polymicrobial growth from abscesses antibiotic coverage was expanded with addition of intravenous metronidazole at 500 mg every 6 hours for empirical coverage of enteric bacteria. Intravenous vancomycin 1250 mg every 12 hours was started for additional extraluminal C. difficile coverage and micafungin 100 mg intravenously every 24 hours was started to cover for Candida infection. Antibiotic coverage was finally switched to intravenous micafungin and oral metronidazole for total 8 weeks of empirical treatment.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged back to inpatient rehabilitation and finally to home. Due to prolonged hospital stay patient was closely followed out patient by infectious disease specialist, surgeon and gastroenterologist. Monthly CT abdomen was done over next 3 months to follow resolution of pancreatic fluid collection.

Discussion

C. difficile is an anaerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive rod and it was recognised as a cause of colitis by Hall and O’Toole in 1935.5 Since its identification, the bacteria has been increasingly identified as leading cause of healthcare acquired infection. Carroll and Bartlett described the recent advances in detection of infection and changing epidemiology with dramatic increase in rates and severity of C. difficile infection noted due to emergence of new hypervirulent strain notably NAP1/BI/027.6 It has been reported that 3% of adults can be healthy asymptomatic carriers.7

Any medication that disrupts the normal bowel flora can increase C. difficile infection and some antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones have emerged as the cause of this imbalance.8 Min and Kim have also described the proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for recurrence of C. difficile infection -associated diarrhoea.9

Extraintestinal C. difficile has been reported in literature, but the extension of the infection beyond intestinal infection has not been well understood and finding the organism at extraintestinal site often is a surprise. Usually, extraintestinal C. difficile infections are found in conjunction with other microbials. Increasing evidence of extraintestinal infection due to Clostridium should be seen as a warning sign. Dauby et al recently reported a case of monomicrobial bacteraemia due to C. difficile and recognised the strain as ribotype 002.10 C. difficile bacteraemia has been reported in 27 adult patients with gastrointestinal disease through 2011 and most of these cases involved polymicrobial bacteraemia.3 11 12

Extraintestinal infection due to C. difficile is a rare finding and usually reported in case reports. Mattila et al did a single-centre study over 10-year period and only 0.17% of the cases were reported to be extraintestinal.13 As reported in this study, 81% of the cases were inpatient and had received antibiotics which increased the risk of infection. Our patient presented with hepatic and pancreatic abscess with polymicrobial infection. With the findings of sigmoid perforation, we consider the cause of infection being translocation of bacteria across the gastrointestinal lumen due to colonic inflammation with direct seeding of the site. Direct spread of C. difficile from the intestine has been reported in previous case reports as well.14–16 Intra-abdominal spread of infection was suspected due to transient bacteraemia in a case of alcoholic cirrhosis with C. difficile isolated from ascitic fluid, but in our patient, blood cultures remained negative.13

Other reported extraintestinal infections include prosthetic joint infections,17 18 osteomyelitis,19 20 splenic abscess,21–23 brain abscess,24 pericardial fluid25 and pleural fluid infections.26 Reactive arthritis due to C. difficile has been reported as well.27–30

C. difficile is rarely identified as a cause of pyogenic liver abscess. As per our PubMed literature search, this is the third reported case of liver abscess due to C. difficile. Sakurai et al and Ulger et al have reported liver abscess due to the organism, and this is a very rare finding.31 32 Sakurai et al reported a case of monomicrobial infection in a 75-year-old woman who had a prior drainage of haemorrhagic liver cyst and was readmitted 2 years later with fever. There was no reported diarrhoea in the patient. The culture from purulent drainage sample reportedly grew the bacteria. They reported local instillation of vancomycin 1500 mg every 8 hours during hospitalisation followed by oral metronidazole therapy.31 Our patient did not receive local instillation of antimicrobials and was different from these prior reported cases due to polymicrobial growth from abscess fluid. Ulger et al reported another case of liver abscess in a 80-year-old, non-hospitalised woman who had no reported diarrhoea or antibiotic use prior to diagnosis of multiple liver abscesses due to the organism.32 Though our patient had the well-known risk factors of recent hospitalisation and antibiotic use prior to the extraintestinal manifestations, increased reporting of abscesses due to the organism in the absence of diarrhoea is a concerning finding and may be a sign of emergence of new toxigenic strains in the asymptomatic carriers.

The identified risk factors for extraintestinal infections are immunocompromised status, recent multiple antibiotic exposure and recent hospitalisation. In addition to these well-known risk factors, Mutlu et al reported altered colonic microbiome in alcoholics which was noted to be similar to enteritis due to C. difficile colitis suggesting alcohol abuse as possible risk factor for C. difficile infection.33 34 Our patient developed extraintestinal infection due to several risk factors including prolonged hospitalisation and recent broad spectrum antibiotic use.

Learning points.

Clostridium difficile is a known cause of colitis and is increasingly reported as the cause of extraintestinal infections. Intra-abdominal infections are the most common extraintestinal site.

Extraintestinal infections have high mortality rate.

The identified risk factors include broad-spectrum antibiotics and prolonged hospitalisation. Antimicrobial stewardship has the potential to reduce the incidence of C. difficile colitis and therefore the extraintestinal complications.

Footnotes

Contributors: MR wrote the initial manuscript. All authors performed literature review, edited the paper and performed data designing. They also read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. . Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015;372:825–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf LE, Gorbach SL, Granowitz EV. Extraintestinal Clostridium difficile: 10 years' experience at a tertiary-care hospital. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73:943–7. 10.4065/73.10.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byl B, Jacobs F, Struelens MJ, et al. . Extraintestinal Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:712 10.1093/clinids/22.4.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libby DB, Bearman G. Bacteremia due to Clostridium difficile--review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis 2009;13:e305–e309. 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee NY, Huang YT, Hsueh PR, et al. . Clostridium difficile bacteremia, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:1204–10. 10.3201/eid1608.100064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman RJ, Kallich M, Weinstein MP. Bacteremia due to Clostridium difficile: case report and review of extraintestinal C. difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20:1560–2. 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bélanger SD, Boissinot M, Clairoux N, et al. . Rapid detection of Clostridium difficile in feces by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:730–4. 10.1128/JCM.41.2.730-734.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall IC, O'Toole E. Intestinal flora in newborn infants with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficilis. Am J Dis Child 1935;49:390–402. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll KC, Bartlett JG. Biology of Clostridium difficile: implications for epidemiology and diagnosis. Annu Rev Microbiol 2011;65:501–21. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, et al. . Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 1989;320:204–10. 10.1056/NEJM198901263200402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile infection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996-2003. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:409–15. 10.3201/eid1205.051064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Min JH, Kim YS. Proton pump inhibitors should be used with caution in critically Ill patients to prevent the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Gut Liver 2016;10:493–4. 10.5009/gnl16216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dauby N, Libois A, Van Broeck J, et al. . Fatal community-acquired ribotype 002 Clostridium difficile bacteremia. Anaerobe 2017;44:1–2. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGill F, Fawley WN, Wilcox MH. Monomicrobial Clostridium difficile bacteraemias and relationship to gut infection. J Hosp Infect 2011;77:170–1. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemminger J, Balada-Llasat JM, Raczkowski M, et al. . Two case reports of Clostridium difficile bacteremia, one with the epidemic NAP-1 strain. Infection 2011;39:371–3. 10.1007/s15010-011-0115-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattila E, Arkkila P, Mattila PS, et al. . Extraintestinal Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:e148–e153. 10.1093/cid/cit392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Lechuz JM, Hernangómez S, Juan RS, et al. . Extra-intestinal infections caused by Clostridium difficile. Clin Microbiol Infect 2001;7:453–7. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keshava A, Collie MH, Anderson DN. Nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection: possible cause of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:764 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikkawa H, Miyamoto K, Takiguchi N, et al. . Surgical-site infection with toxin A-nonproducing and toxin B-producing Clostridium difficile. J Infect Chemother 2008;14:59–61. 10.1007/s10156-007-0568-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pron B, Merckx J, Touzet P, et al. . Chronic septic arthritis and osteomyelitis in a prosthetic knee joint due to Clostridium difficile. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1995;14:599–601. 10.1007/BF01690732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy J, Stingemore N. Clostridium difficile infection of a prosthetic joint presenting 12 months after antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. J Infect 1999;39:94–6. 10.1016/S0163-4453(99)90110-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley TV, Karthigasu KT. Chronic osteomyelitis due to Clostridium difficile. Br Med J 1982;284:1217–8. 10.1136/bmj.284.6324.1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Incavo SJ, Muller DL, Krag MH, et al. . Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by Clostridium difficile. A case report and review of the literature. Spine 1988;13:111–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saginur R, Fogel R, Begin L, et al. . Splenic abscess due to Clostridium difficile. J Infect Dis 1983;147:1105 10.1093/infdis/147.6.1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Studemeister AE, Beilke MA, Kirmani N. Splenic abscess due to Clostridium difficile and Pseudomonas paucimobilis. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;82:389–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemminger J, Balada-Llasat JM, Raczkowski M, et al. . Two case reports of Clostridium difficile bacteremia, one with the epidemic NAP-1 strain. Infection 2011;39:371–3. 10.1007/s15010-011-0115-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gravisse J, Barnaud G, Hanau-Berçot B, et al. . Clostridium difficile brain empyema after prolonged intestinal carriage. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:509–11. 10.1128/JCM.41.1.509-511.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng L, Citron DM, Genheimer CW, et al. . Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibilities of extra-intestinal Clostridium difficile isolates. Anaerobe 2007;13:114–20. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simpson AJ, Das SS, Tabaqchali S. Nosocomial empyema caused by Clostridium difficile. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:172–3. 10.1136/jcp.49.2.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löffler HA, Pron B, Mouy R, et al. . Clostridium difficile-associated reactive arthritis in two children. Joint Bone Spine 2004;71:60–2. 10.1016/S1297-319X(03)00056-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobs A, Barnard K, Fishel R, et al. . Extracolonic manifestations of Clostridium difficile infections. presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine 2001;80:88–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birnbaum J, Bartlett JG, Gelber AC. Clostridium difficile: an under-recognized cause of reactive arthritis? Clin Rheumatol 2008;27:253–5. 10.1007/s10067-007-0710-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prati C, Bertolini E, Toussirot E, et al. . Reactive arthritis due to Clostridium difficile. Joint Bone Spine 2010;77:190–2. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakurai T, Hajiro K, Takakuwa H, et al. . Liver abscess caused by Clostridium difficile. Scand J Infect Dis 2001;33:69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulger Toprak N, Balkose G, Durak D, et al. . Clostridium difficile: A rare cause of pyogenic liver abscess. Anaerobe 2016;42:108–10. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, et al. . Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2012;302:G966–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manges AR, Labbe A, Loo VG, et al. . Comparative metagenomic study of alterations to the intestinal microbiota and risk of nosocomial clostridum difficile-associa disease. J Infect Dis 2010;202:1877–84. 10.1086/657319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]