Abstract

Background:

The rate of early sport specialization in professional baseball players is unknown.

Purpose:

To report the incidence and age of sport specialization in current professional baseball players and the impact of early specialization on the frequency of serious injuries sustained during the players’ careers. We also queried participants about when serious injuries occurred, the players’ current position on the field, and their opinions regarding the need for young athletes to specialize early to play at the professional level.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiological study.

Methods:

A total of 102 current professional baseball players anonymously completed a 7-question written survey. Early sport specialization was defined as “single-sport participation prior to high school.” Injury was defined as “a serious injury or surgery that required the player to refrain from sports (baseball) for an entire year.” Chi-square tests were used to investigate the risk of injury in those who specialized early in baseball versus those who did not. Independent-sample t tests were used to compare injury rates based on current player position.

Results:

Fifty (48%) baseball players specialized early. The mean age at initiation of sport specialization was 8.91 years (SD, 3.7 years). Those who specialized early reported more serious injuries (mean, 0.54; SD, 0.838) during their professional baseball career than those who did not (mean, 0.23; SD, 0.425) (P = .044). Finally, 63.4% of the queried players believed that early sport specialization was not required to play professional baseball.

Conclusion:

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant higher rate of serious injury during a baseball player’s professional career in those players who specialized early. Most current professional baseball players surveyed believed that sport specialization was not required prior to high school to master the skills needed to play at the professional level. Our findings demonstrate an increased incidence of serious injuries in professional baseball players who specialized in baseball prior to high school. Youth baseball athletes should be encouraged not to participate in a single sport given the potential for an increased incidence of serious injuries later in their careers. No data are available to suggest that early specialization is needed to reach the professional level.

Keywords: early sport specialization, injury prevention, professional baseball, youth sports

Early sport specialization in youth athletes has been increasing progressively, to the point that 77.7% of high school athletic directors have reported an increase in this trend.16,23 Jayanthi et al15 popularized the definition of sport specialization as “year-round [8+ months/year] intensive training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports.” The trend toward specializing early (ie, before high school age) in a single sport is multifactorial in nature but is likely driven by the idea that if an athlete focuses on one sport, his or her athletic performance in that sport will be better than the performance of those who play multiple sports. The concept of specialization improving human performance was buoyed by a study by Ericsson et al,6 who predicted expert performance based on the duration of exposure (practice) with development of the all-too-famous “10,000-hour rule.” However, the effectiveness of increasing the amount of early exposure to a single sport on athletic performance is still being debated.10 Injuries in baseball have been a focus of attention for those studying injury rates and patterns in youth sports for some time. Modifiable risk factors for injury have been studied in youth pitchers and have led to alterations in pitching practices for this group.7,10,21–23

To our knowledge, no studies of current professional baseball players have compared injury rates in those who specialized early compared with those athletes who did not. The purpose of this study was to report the incidence and age of sport specialization in current professional baseball players and the impact of early specialization on the frequency of serious injuries sustained during the players’ careers. Also, participants were queried about when serious injuries occurred, their current position on the field, and their opinions regarding the need for young athletes to specialize early in order to play at the professional level.

Methods

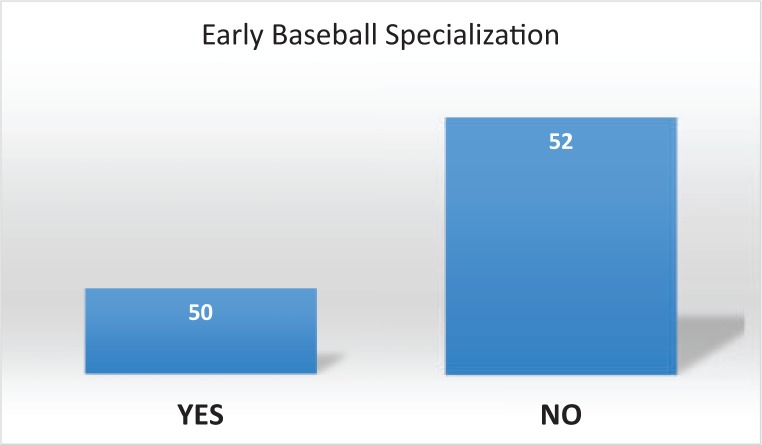

This study involved 102 participants (aged 22-40 years) who were active professional baseball players during the 2016 season in the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball, which is an independent professional league comprised of 8 teams. The players were provided a 7-question written survey in either English or Spanish; in addition, players were asked to provide their current age and current position played (Figure 1). A total of 8 teams, with 30 players at maximum on each roster, allowed for a total of 240 potential participants. Participation in this survey was voluntary, and the player responses remained anonymous. Survey completion was proctored by the team’s licensed athletic trainer.

Figure 1.

English-language version of survey distributed to baseball players.

Players were asked whether they had specialized in baseball prior to high school and were queried as to the age at which they specialized. Our definition of sport specialization was “intense, year-round training in a single sport with the exclusion of other sports.” We inquired about serious injury and when the injury occurred. Injury was defined as a baseball-related injury or surgery that required the player to refrain from the sport for an entire year. Finally, athletes were asked whether they believed that early sport specialization (ie, prior to high school) was required to play at the professional level.

Data from the surveys were complied, and differences were considered significant at P < .05. Chi-square tests were used to investigate the relationship of injury risk at the youth and professional levels based on the participant’s age at the time of sport specialization. Players were designated into 4 position categories: pitcher, catcher, infield, or outfield. Independent-samples t tests were used to compare injury rates based on player position.

Results

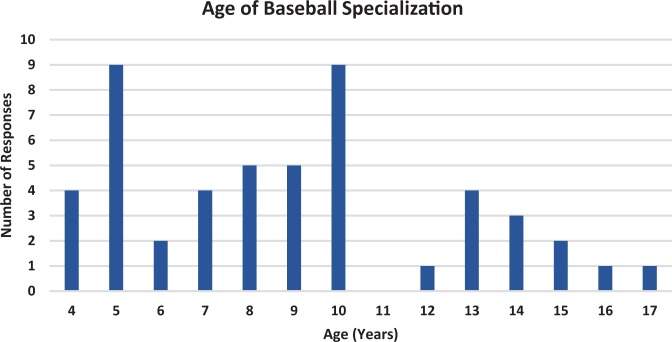

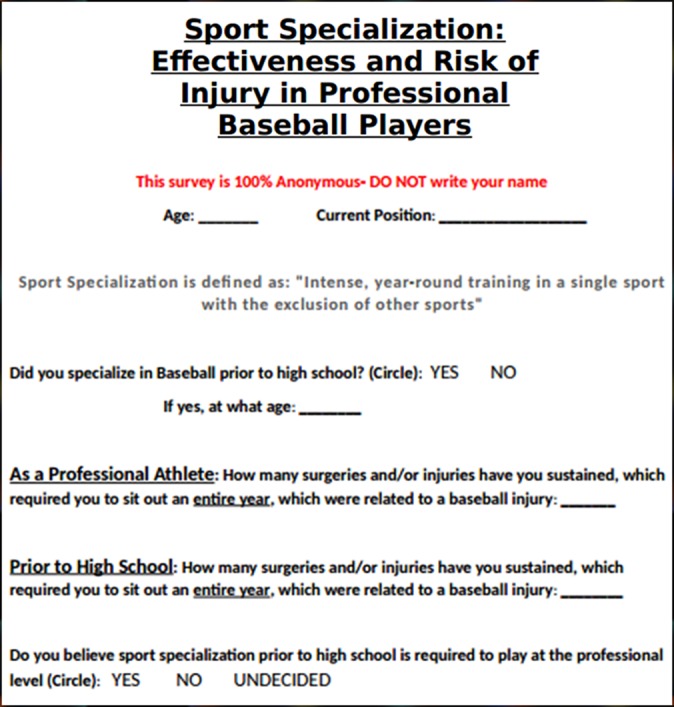

A total of 102 professional baseball players took part in the study during the 2016 baseball season. Participants ranged from 22 to 40 years of age, and the mean age was 29. Fifty (49%) participants specialized early in baseball (Figure 2). Overall, baseball specialization began at age 4 to 17 years, with the mean age being 8.91 years (Figure 3). Additional player characteristics are provided in Table 1. One player did not identify his current playing position while another did not give his opinion on the need for sport specialization to play at the professional level; both players were included in all data analysis.

Figure 2.

Number of players who specialized early in baseball (N = 102).

Figure 3.

Age at which professional players specialized in baseball (n = 50).

TABLE 1.

Player Characteristicsa

| Position | ||

| Catcher | 13 (12.9) | |

| Infield | 25 (24.8) | |

| Outfield | 17 (16.8) | |

| Pitcher | 46 (45.5) | |

| Specialized early in baseballb | ||

| No | 52 (51.0) | |

| Yes | 50 (49.0) | |

| Believe early sport specialization is helpful | ||

| No | 64 (63.4) | |

| Undecided | 10 (9.9) | |

| Yes | 27 (26.7) | |

| Age at specialization, y, mean ± SD | 8.91 ± 3.7 |

aValues given as n (%) of players unless otherwise indicated.

bDefined as before high school age.

Thirty-two players reported 1 or more serious injuries as a professional baseball player, with the maximum being 4. Those who specialized early reported more injuries (mean, 0.54; SD, 0.838) as a professional baseball player than those who did not specialize early (mean, 0.23; SD, 0.425) (P = .044). A total of 3 players reported having a serious injury while participating in youth baseball, which revealed no significant difference between those who specialized early and those who did not. No association was found between injury rates and the players’ current position. The majority of current professional baseball players (63.4%) believed that sport specialization prior to high school was not required to achieve the skills necessary to play professionally.

Discussion

Although the rate of early sport specialization in young athletes has been studied, the downstream effects of early specialization on professional athletes have not.16,23 Our study is the first to report the incidence of early sport specialization in professional baseball players while also reporting on variables such as injury incidence and age at specialization. Two previous studies have assessed sport specialization in professional baseball players. Hill13 reported that a large proportion of professional baseball players had played basketball and football in high school; in addition to playing baseball, 68.7% had played basketball and 59.3% had played football in high school. The author did not evaluate injury incidence in the study group or report the age at which the players specialized.13 Ginsburg et al11 reported that 25% of professional players specialized before age 12 and the mean age of specialization was 15; again, injury rates were not discussed. In contrast, our study demonstrated that 49% of players specialized in baseball prior to high school.

Factors contributing to the bimodal distribution of the player’s age at specialization may be both geographic and cultural. At the start of the 2016 season, 28.5% of Major League Baseball (MLB) players were of Latin American origin.18 Baseball is largely a warm weather outdoor sport. Players who grew up in warmer climates may have had more opportunity to participate in baseball year-round and therefore specialized earlier.

A 3% increase has been noted in organized sports activity participation from 1997 to 2008 in children younger than 7 years.23 This trend is likely to continue with the heightened awareness and media attention on successful elite athletes worldwide, along with the financial compensation those athletes receive for their professional success.

The trend toward sport specialization is multifactorial in nature but is likely driven by the idea that if an athlete focuses on one sport, his or her athletic performance will be superior to those who play multiple sports during the calendar year. Other potential benefits to early specialization, besides giving the athlete an edge in competition, include early exposure to collegiate and professional scouts and the downstream potential for financial rewards such as scholarships for college or the potential to sign a professional contract. The sobering fact is that approximately 1 in 200, or 0.5%, of high school senior boys playing interscholastic baseball in the United States will eventually be drafted by an MLB organization.7 Even fewer players actually play in the major leagues. Although parents often appear to be the driving factor for a single sport focus, multiple studies have demonstrated that the coach may be the most influential in this decision process.16 Youth coaches may believe that expert skills will be achieved only if the athlete’s focus is directed to a single activity or sport. This prevailing thought potentially comes from a study by Ericsson et al,6 who predicted expert human performance with development of the “10,000-hour rule.” In that study, the investigators determined that it would take around 10,000 hours of dedicated practice before expert level performance would be attainable. Although the study was focused on the skills developed by students of a musical instrument, it seems reasonable that specialization may have similar results on a sporting field as well.

The exact age at which to specialize in a single sport and the time it takes to acquire the skill set needed to reach the professional level are far from established and likely are different for each individual player.9 For the professional baseball players who completed our survey, the mean age of baseball specialization was 8.91 years. Intuitively, it makes sense that specializing at an early age to master sport-specific skill sets would be beneficial to all athletes, but some studies have suggested that specialization later in childhood may lead to increased athletic achievement.4,12,16,17,20 Carlson4 found that elite tennis players in Sweden reported later sport specialization compared with near-elite players. Gullich and Emrich12 studied German Olympic athletes and found that the elite athletes specialized later and were more likely to have participated in more than one sport past the age of 11 years. Lidor and Lavyan20 discovered similar results, reporting that individuals were more likely to be multisport athletes under the age of 11 and began to specialize after age 12. The age range of sport specialization may vary greatly depending on multiple factors, such as the actual sport or the sexual or neurocognitive development of the athlete. For instance, many female ballet dancers will not go en pointe until menarche due to stress on the hallux physes. Studies such as these demonstrate that we still do not have a clear understanding of when and whether sport specialization should occur in our youth.

Much debate remains regarding when and whether single-sport specialization may be harmful. In our study, we found a statistically significant increase in risk of a serious injury as a professional athlete if the player had specialized prior to high school. Interestingly, only 3 professional athletes reported sustaining a serious injury prior to high school; thus, in this study there was no correlation between specialization and injury as a youth athlete. Rose et al26 studied high school athletes of all sports and found that increased exposure to sport was the most important risk factor for injury. Baseball in particular has been a focus of attention for those studying injury rates and patterns in youth sports. Fleisig et al10 followed youth baseball pitchers for 10 years and found that those who pitched more than 100 innings per year were 3.5 times more likely to be injured. Other investigators found a significantly increased risk of shoulder or elbow surgery if athletes pitched more than 8 months out of the year.25 A multitude of variables may affect injury rates from sport-specific training and specialization; thus, to pinpoint one specific cause is extremely difficult.

Concerns about the effects of early specialization on injury rates and psychological burnout have led at least 7 sport authorities to publish position statements on sport specialization.1–3,9,14,24 After an internal review of the current literature, USA Baseball, USA Cycling, and USA Swimming have initiated recommendations related to youth athletes in regard to pitch counts, gear ratios, and practice times, respectively.8 The American Orthopaedic Society of Sports Medicine published a consensus statement in 2016 and concluded that no evidence is available to show that youth athletes will benefit from early sport specialization in the majority of sports and that early multisport participation will not be detrimental to future athletic success.19

While the caveats of our study include low sensitivity to statistical analysis due to a relatively small sample size for mean (and median) number of injuries, our data seem to support the notion that early sport specialization in youth may contribute to an increased number of serious injuries as a professional baseball player. Including more study participants would have helped solidify this association.

This study is also limited by recall bias based on the recollection of serious injuries sustained many years ago by the participants. While it may be easier to recall such events in those who are young and healthy, some participants were asked to recall life events that occurred up to 36 years previously. This potentially could have resulted in underreporting of serious injuries prior to high school level.

To help reduce recall bias, we limited the definition of “injury” to a baseball-related injury, or surgery related to a baseball injury, that required the player to refrain from sports for an entire year. Unfortunately, by establishing return to sport at 1 year, we may have introduced a selection bias by underreporting some significant injuries that may have kept an athlete out of competition for 6, 9, or even 11 months. This would have falsely lowered the injury rates seen in both the pre–high school and the professional settings.

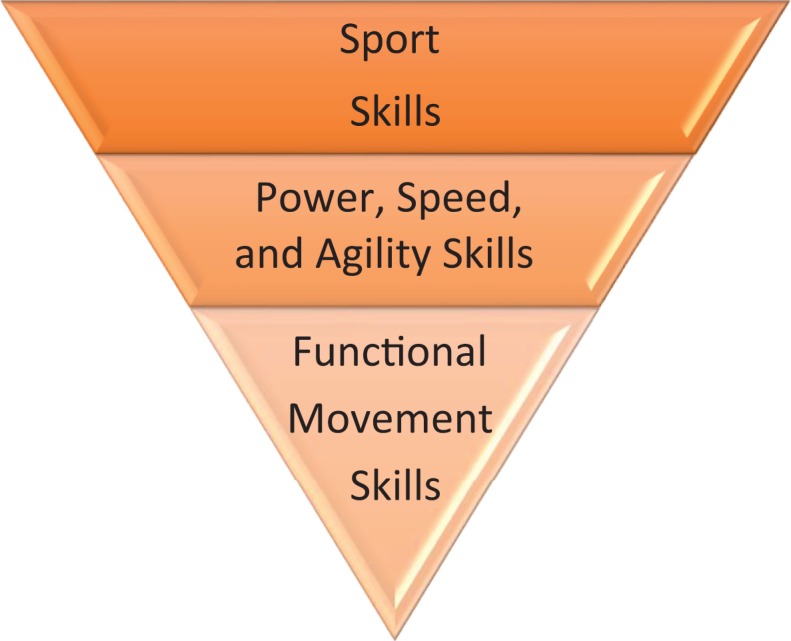

Our study included all serious baseball-related injuries. We did not specifically query whether the injury involved the player’s throwing arm. Some may propose that this is a weakness of the study; however, we believe that early specialization may increase the risk of all injuries, not just overuse injuries to the dominant extremity. Athletes specializing early in a single sport are prone to develop an inverted athletic performance pyramid (Figure 4) by focusing on sport-specific skills at the expense of sound fundamental movement patterns. A failure to develop sound functional movement patterns may place the entire kinetic chain at risk.

Figure 4.

Inverted performance pyramid.5

Conclusion

Professional baseball players may be at higher risk of sustaining a serious injury during their career if they specialized early in baseball during their youth. The current study was unable to show that early baseball specialization increased risk of injury for these players prior to turning professional. A player’s position was not associated with injury in this study. As only 49% of the players who responded to our survey specialized in baseball before high school, it is evident that sport specialization as a child is not required to reach the professional level. A total of 63% of the professional athletes in our survey believed that sport specialization was not required to play baseball at the professional level. Youth athletes should be encouraged to play multiple sports through high school, with the knowledge that doing so will not hinder their potential to become a professional baseball player.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Craig Ruder, MD, Erika Stitler, PAC, Kate Kelly, MLS, and Rod Grim, PhD, for their assistance in editing and statistics for this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by WellSpan Health IRB.

References

- 1. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Intensive training and sports specialization in young athletes. Pediatrics. 2000;106:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American College of Sports Medicine. The prevention of sport injuries of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1993;25(8):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armstrong MN, Bar-Or O, Boreham C, et al. Sports and children: consensus statement on organized sports for children: FIMS/WHO Ad Hoc Committee on Sports and Children. Bull World Health Org. 1998;76(5):445–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlson R. The socialization of elite tennis players in Sweden: an analysis of the players’ backgrounds and development. Sociol Sport J. 1988;5:241–256. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cook G. Chapter 10: understanding corrective strategies In: Cook G, ed. Movement: Functional Movement Systems. Aptos, CA: On Target Publication; 2010:6764–7327. https://www.amazon.com/Movement-Gray-Cook-ebook/dp/B0079QQCHI/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1505761957&sr=1-1. Accessed May 11 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(3):363–406. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Estimated probability of competing in professional athletics. NCAA Research. http://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/research/estimated-probability-competing-professional-athletics. Updated April 25, 2016. Accessed February 21, 2017.

- 8. Feeley B, Agel J, LaPrade RF. When is it too early for single sport specialization? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferguson B, Stern P. A case of early sports specialization in an adolescent athlete. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(4):377–383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fleisig G, Andrews J, Cutter G, et al. Risk of serious injury for young baseball pitchers: a 10-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ginsburg RD, Smith SR, Danforth N, et al. Patterns of specialization in professional baseball players. J Clin Sport Psychol. 2014;8:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gullich A, Emrich E. Evaluation of the support of young athletes in the elite sports system. Eur J Sport Sci. 2006;13(3):85–108. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hill G. Youth sport participation of professional baseball players. Sociol Sport J. 1993;10:107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hughson R. Children in competitive sports: a multi-disciplinary approach. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1986;11(4):162–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jayanthi NA, LaBella CR, Fischer D, et al. Sports-specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jayanthi N, Pinkham C, Dugas L, et al. Sports specialization in young athletes: evidence based recommendations. Sports Health. 2013;5(3):251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jayanthi NA, Pinkham C, Durazo-Arivu R, et al. The risks of sports specialization and rapid growth in young athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(2):157. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lapchick R. Major League Baseball racial and gender report card. The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. http://tidesport.org/mlb-rgrc.html. Accessed February 21, 2017.

- 19. LaPrade RF, Agel J, Baker J, et al. AOSSM early sport specialization consensus statement. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(4):23259 67116644241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lidor R, Lavyan A. A retrospective picture of early sport experiences among elite and near-elite Israeli athletes: developmental and psychological perspectives. Int J Sport Psychol. 2002;33:269–289. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, et al. Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Waterbor JW, et al. Longitudinal study of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1803–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malina RM. Early sport specialization: roots, effectiveness, risks. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9(6):364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McLeod TCV, Decoster L, Loud KJ, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: prevention of pediatric overuse injuries. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olsen SJ, Fleisig GS, Dun S, et al. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):905–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rose MS, Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. Sociodemographic predictors of sport injury in adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(3):444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]