Abstract

Background:

Youth athlete specialization has been linked to decreased enjoyment, burnout, and increased injury risk, although the impact of specialization on athletic success is unknown. The extent to which parents exert extrinsic influence on this phenomenon remains unclear.

Purpose/Hypothesis:

The goal of this study was to assess parental influences placed on young athletes to specialize. It was hypothesized that parents generate both direct and indirect pressures on specialized athletes.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

A survey tool was designed by an interdisciplinary medical team to evaluate parental influence on youth specialization. Surveys were administered to parents of the senior author’s orthopaedic pediatric patients.

Results:

Of the 211 parents approached, 201 (95.3%) completed the assessment tool. One-third of parents stated that their children played a single sport only, 53.2% had children who played multiple sports but had a favorite sport, and 13.4% had children who balanced their multiple sports equally. Overall, 115 (57.2%) parents hoped for their children to play collegiately or professionally, and 100 (49.7%) parents encouraged their children to specialize in a single sport. Parents of highly specialized and moderately specialized athletes were more likely to report directly influencing their children’s specialization (P = .038) and to expect their children to play collegiately or professionally (P = .014). Finally, parents who hired personal trainers for their children were more likely to believe that their children held collegiate or professional aspirations (P = .009).

Conclusion:

Parents influence youth athlete specialization both directly and by investment in elite coaching and personal instruction. Parents of more specialized athletes exert more influence than parents of unspecialized athletes.

Keywords: sports specialization, parental influence, burnout, youth sports

As organized youth sports participation in the United States grows beyond 30 million children annually,1 epidemiological patterns of injury are being increasingly studied. It has recently been shown that more than 2.5 million annual sports injuries were reported in patients 24 years or younger,8 and at least half of sports injuries presenting in the emergency room were overuse injuries.22

A contributing factor to the epidemic of overuse injuries is youth athlete specialization. The American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) defines early sports specialization as focusing on a sport to the exclusion of other sports and playing and training in the sport more than 8 months per year prior to the age of 12.16 Physician organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and AOSSM uniformly have advocated against early sports specialization.13,16 Numerous investigations have demonstrated the detrimental sequelae of early specialization, including burnout, overuse injury, and decreased enjoyment.5,6,10,12,19 Jayanthi et al14 recently analyzed a cohort of more than 1000 patients between 7 and 18 years of age, showing that more than 60% of patients were at least moderately specialized and that these patients specialized before age 12 on average.

While the consequences of youth specialization are being investigated, the extrinsic pressures placed by parents have yet to be comprehensively quantified. Specific examples of deleterious parental pressures have been identified. For instance, studies have shown that one-third of players reported being encouraged to continue playing by a parent and/or coach despite admitting an injury.2,18 Another investigation demonstrated that almost one-fourth of youth athletes reported experiencing pressure from adults, including parents and coaches, to continue playing after a concussion.15

Parental encouragement has been found to be vital in establishing children’s longitudinal involvement in youth athletics.23 Both with verbal encouragement and by participating in active lifestyles themselves, parents largely influence their children’s participation in youth sports.11,17 Transporting these young athletes to and from practice, purchasing new equipment, arranging additional instruction, and counseling their children following injuries are all roles that parents assume to enrich their children’s sporting experiences. However, parental pressure and behavior strongly modify the child’s sports experience and have been found to potentially decrease athletes’ enjoyment of the sport3,9,20 by inducing perfectionistic expectations4 and increasing anxiety.7

The psychosocial impact that parents have on their children’s sports experience can be substantial. Although recent studies have demonstrated the pernicious consequences of youth specialization, the parental role in this phenomenon remains unclear. The goal of this study was to evaluate direct and indirect parental influences in youth specialization. We hypothesized that parents significantly influence highly specialized athletes both by direct pressure and indirectly through resource allocation.

Methods

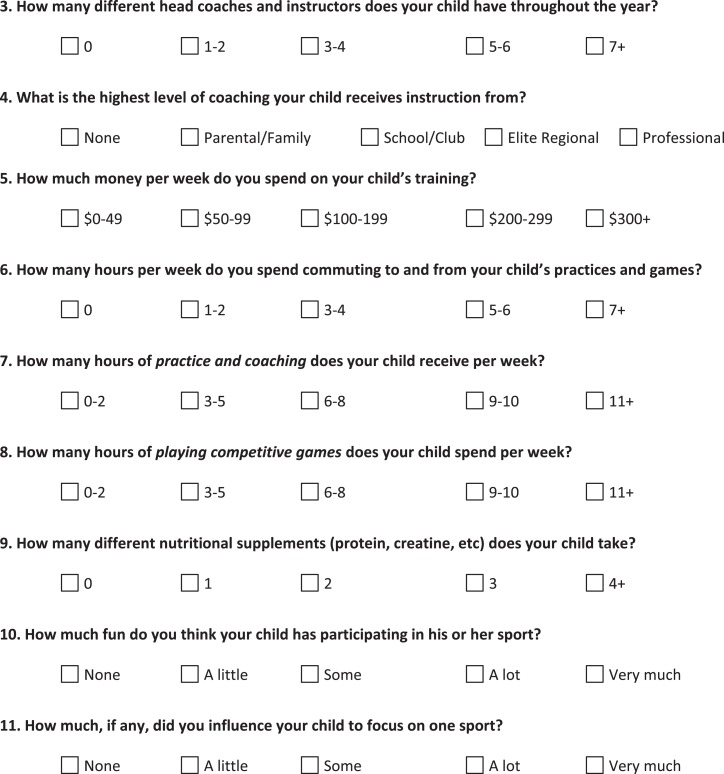

Institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct this study. The survey instrument (available in the Appendix) was designed with the goal of comprehensively assessing parents’ engagement in their children’s sporting activities. The instrument was generated by an interdisciplinary team including pediatric and sports medicine orthopaedic surgeons, parents, coaches, athletic trainers, and training academy instructors.

The survey consisted of 2 aggregate sections: a demographics section and an 11-question section evaluating the parents’ involvement in their children’s sports specialization. Demographic variables included the child’s age, sex, favorite sport, level of specialization, presence of personal trainers and instructors, injury history, and surgical history. The parents’ influence on their children’s specialization was assessed with 11 questions regarding the parents’ time and resource commitment, the parents’ perception of the child’s enjoyment, the placement of direct pressure to specialize, and the type and level of coaching the child receives. Each of these questions was evaluated by use of a 5-point Likert scale.

The instrument was administered to the parents of youth athletes seen in the office of the senior author, a pediatric and sports medicine orthopaedic surgeon (C.A.P.). Inclusion criteria consisted of having a child between 7 and 18 years of age who participated in an organized sport, ability to speak English or Spanish, and lack of mental disability. Incomplete responses were excluded from data analysis. While no parent refused participation in the study, 10 parents began the survey without completing it.

Statistical Analysis

Responses were collected by use of independent survey software (Qualtrics). Chi-square tests of independence were used to assess the frequency of responses to the 5-point Likert scale questions between distinct study cohorts (separated by injury history, personal instructors, level of specialization). The chi-square test was selected because nonparametric functions are best able to evaluate the integers inherent to a Likert scale. Findings were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

The final instrument was administered to 211 parents, of whom 201 completed responses (95.3% completion rate). The majority of parents who completed the survey were female (71.4%), while 58.2% of youth athletes were male. The mean age ± SD of the surveyed parents’ children was 13.8 ± 3.0 years. Regarding medical history, 72.1% of parents stated that their children had experienced a sports-related injury. Injury severity ranged from nonoperative conditions, including medial epicondylitis and patellar tendinitis, to operative conditions such as anterior cruciate ligament rupture and ulnar collateral ligament rupture. Approximately 25.1% of parents had hired personal trainers, and 22.9% had hired sports-specific instructors for their children. A summary of key demographic variables is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographicsa

| Parent sex, % female | 71.4 |

| Child sex, % male | 58.2 |

| Youth athlete age, y | 13.8 ± 3.0 |

| Overuse injury history, % | 72.1 |

| Surgical history, % | 16.6 |

| Child’s favorite sport, % | |

| Soccer | 25.9 |

| Basketball | 19.4 |

| Baseball/softball | 15.4 |

| Lacrosse | 8.5 |

| Cross country/track and field | 7.5 |

| Otherb | 23.4 |

aValues expressed as percentages except for age (mean ± SD).

bMore than 2% each: football, track and field, swimming, tennis.

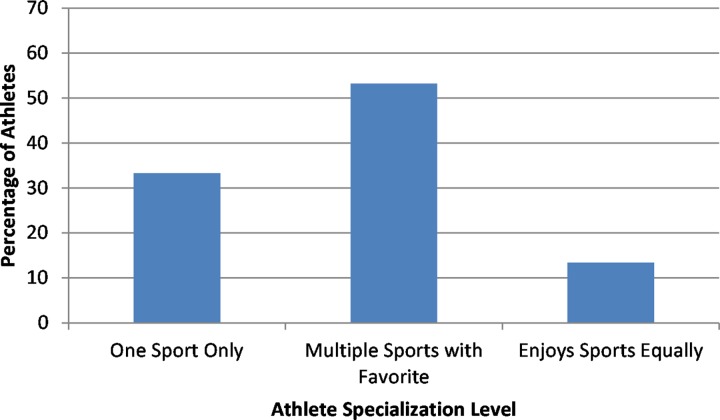

The parents were asked to assess the level of specialization of their children. Exactly one-third (n = 67) of parents stated their children focused on one sport only, 53.2% (n = 107) stated that their children played multiple sports but had a favorite sport, and 13.4% (n = 27) stated that their children equally liked all of the sports they played. Figure 1 demonstrates these findings.

Figure 1.

Parent-assigned youth specialization level.

The responses to the 11 questions assessing level of specialization and parental resource allocation with a 1-5 Likert scale were tabulated, and responses are displayed in Table 2. Of the 201 respondents, 57.2% of parents hoped for their children to play collegiately or professionally, and 58.8% of parents believed their children desired the same. Approximately 43% of the surveyed parents’ children had at least 3 different coaches. Only 45.3% of parents stated that they never influenced their children to focus on a single sport. Finally, 6.3% of parents stated that they would hold back their child an academic year solely to provide the child with an athletic advantage.

TABLE 2.

Parent Specialization Survey Responses by Question Type

| Survey Question | % |

|---|---|

| Questions regarding aspirations | |

| What is the highest level of play your child hopes to reach? | |

| Just for fun | 13.9 |

| Travel team | 6.5 |

| Varsity | 20.9 |

| College | 29.4 |

| Professional | 29.4 |

| What is the highest level of play you hope your child reaches? | |

| Just for fun | 11.9 |

| Travel team | 5.5 |

| Varsity | 25.4 |

| College | 36.8 |

| Professional | 20.4 |

| Questions regarding coaching | |

| How many coaches and instructors does your child have per year? | |

| 0 | 5.0 |

| 1 or 2 | 51.7 |

| 3 or 4 | 34.3 |

| 5 or 6 | 4.5 |

| ≥7 | 4.5 |

| What is the highest level of instruction your child receives? | |

| None | 3.0 |

| Family | 4.5 |

| School/club | 63.2 |

| Elite | 17.9 |

| Professional | 11.4 |

| Questions regarding parental influence | |

| How much did you influence your child to focus on one sport? | |

| None | 45.3 |

| A little | 19.4 |

| Some | 19.4 |

| A lot | 9.5 |

| Very much | 6.5 |

| Would you hold your child back a year to gain an athletic advantage?a | |

| Yes | 6.3 |

| No | 93.7 |

| Questions regarding time commitment of primary sport | |

| How many hours of practicing and coaching does your child receive per week? | |

| 0-2 | 22.9 |

| 3-5 | 34.3 |

| 6-8 | 20.9 |

| 9-10 | 7.5 |

| ≥11 | 14.4 |

| How many hours of playing competitive games does your child spend per week? | |

| 0-2 | 46.3 |

| 3-5 | 40.8 |

| 6-8 | 8.5 |

| 9-10 | 3.0 |

| ≥11 | 1.5 |

an = 158 responses.

Level of Specialization

Parents of athletes who played either one sport only (highly specialized) or multiple sports with a favorite (moderately specialized) were more likely to believe that their children had collegiate or professional aspirations than were parents of unspecialized children. While 60.9% of parents of specialized athletes believed that their children had collegiate or professional aspirations, only 44.4% of parents of unspecialized athletes believed the same (P = .014). Additionally, specialized parents were more likely to have directly influenced their children’s specialization. While 17.8% of specialized parents influenced their child to specialize “a lot” or “very much,” only 3.7% of parents of unspecialized athletes stated the same (P = .038). Last, while 7.2% of specialized parents stated that they would hold their child back an academic year to gain an athletic advantage, none of the parents of unspecialized athletes stated they would do the same. This finding was not statistically significant (P = .229).

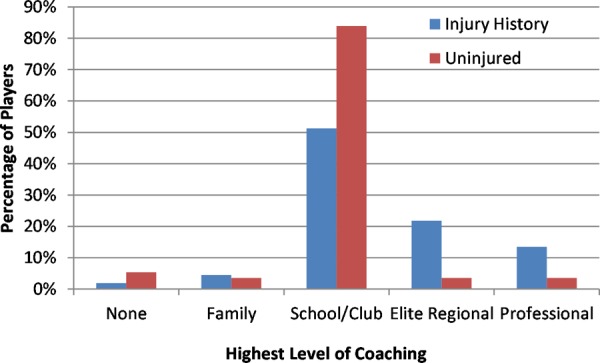

History of Sports-Related Injury

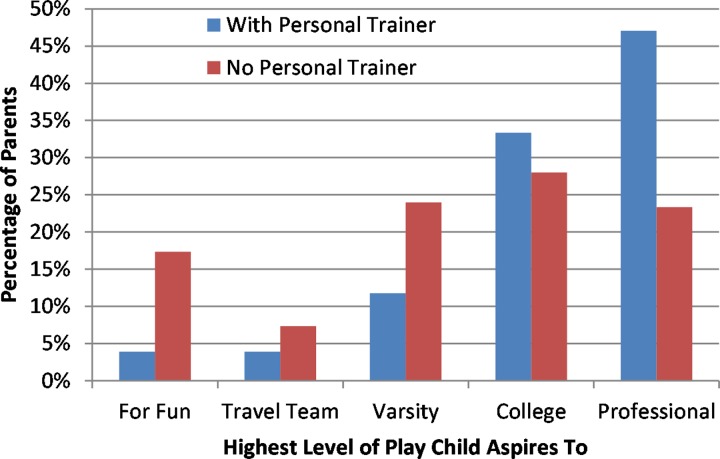

Of the 201 respondents, 145 (72.1%) reported that their children had experienced a sports-related injury. Children with an injury history were more likely to receive instruction from elite regional or professional coaches. While 37.9% of players with an injury history received instruction from elite regional or professional coaches, only 7.1% of players without an injury history reported the same (P < .001). These findings are fully displayed in Figure 2. Additionally, parents reported that players with an injury history were more likely to practice 9 or more hours per week than players without an injury history. While 27.6% of players with an injury history practiced for 9 or more hours per week, only 8.9% of players without an injury history did the same (P = .018).

Figure 2.

Percentage of players receiving each level of coaching separated by injury history. Players with an injury history were significantly more likely to receive elite regional or professional coaching (P < .001).

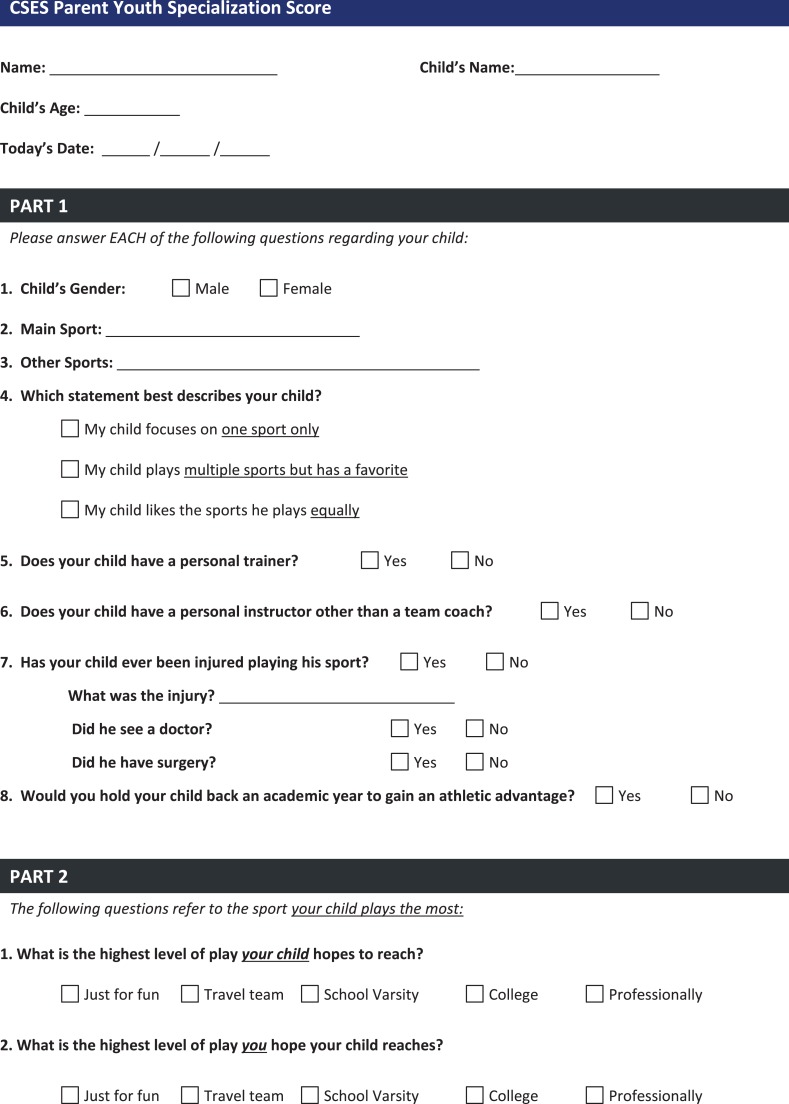

Responses Analyzed by Hiring of Personal Trainer

The responses were analyzed after separating the parents who hired a personal trainer for their children (n = 56; 27.9%) from those who did not (n = 155; 77.1%). Parents who hired personal trainers for their children were more likely to have collegiate or professional aspirations for their children. While 74.5% of parents who hired personal trainers for their children hoped for their children to reach collegiate or professional play, only 49.3% of parents who did not hire a personal trainer believed the same (P = .031). Parents who hired personal trainers for their children were also more likely to believe that their children aspired to play collegiately or professionally. Approximately 80% of parents who hired personal trainers for their children believed that their children aspired to play professionally or collegiately compared with 51.3% of parents who did not hire trainers (P = .009). These findings are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Frequency of players’ highest aspirations of play as separated by the presence of a personal trainer. Parents who hired personal trainers were significantly more likely to believe their children desired to play collegiately or professionally (P = .009).

Discussion

Youth athlete specialization has been linked to increased injury risk, burnout, and decreased enjoyment of playing sports.10,21 Despite these concerning links, athletes are increasingly specializing prior to age 12.5,14 While the impetus behind this trend is likely multifactorial, extrinsic pressure, including parental pressure, has been identified as a potential contributor to overuse injury.15,18 This study reveals novel insight into pressures that parents place on children to specialize in a single sport.

This study demonstrates that significant external pressures are being placed on specialized athletes directly from parents and high-level coaches. While few youth athletes reach collegiate play, the majority of parents of specialized athletes have personal aspirations and expect their children to aspire to play at the collegiate or professional level. While this study adds to the association between high weekly practice time and injury incidence,9 a novel potential link between coaching level and injury risk was also shown. Athletes who received instruction from elite coaches were significantly more likely to have experienced a sports-related injury than athletes who received instruction only from school coaches or family members. The confounders contributing to this finding were not controlled, however. Athletes with more coaching and higher aspirations likely practice more frequently and participate in more leagues, contributing to increased exposure and injury risk. Future studies should control for confounding variables to demonstrate a link between level of coaching and youth athlete injury risk.

The results of this study indicate that a positive feedback cycle likely exists between parental investment and youth athlete specialization. While athletes who succeed in a sport are intrinsically more likely to play that sport more frequently, specific extrinsic influences were also identified. Hiring specialized coaches for youth athletes was accompanied by increased expectations of collegiate or professional play. Parents of specialized athletes simultaneously endorsed directly influencing their children’s trajectory in focusing on a single sport. Additionally, the approach of parents of specialized athletes expanded beyond coaching and aspirations. While not statistically significant, no parents from the nonspecialized athlete cohort stated that they would hold back their children in school in order to gain an athletic advantage, whereas 7.2% of parents in the specialized cohort said they would do this. This shows the importance of children’s athletic performance and success to a contingent of parents of specialized athletes.

As sports medicine physicians and pediatricians continue to address the epidemic of youth overuse injuries, this study demonstrates striking trends from a novel perspective. Parental influence upon youth sports enjoyment can be substantial,3,9,11,23 and this study helps to characterize the direct and indirect pressures that parents place on their children to specialize. This study also adds to existing literature18 that coaches directly contribute to youth athlete specialization, with higher-level coaches likely influencing young athletes the most.

The study has several limitations. It was conducted in an extremely competitive region and may not reflect the nation as a whole. As these patients were presenting to an orthopaedic surgeon, results are likely skewed compared with young athletes in general across the nation.

The high percentage of athletes receiving instruction from elite coaches and whose parents had hired personal trainers and/or instructors is specific to competitive athletes of a given socioeconomic status and may not be generalizable to the nation as a whole. Future studies may contrast the data from this study to other populations to analyze the impact of these aspects upon injury risk and specialization. Also, the instrument used was created for this study and has not yet been validated.

Despite anonymous submission, fear of judgment from the orthopaedic physicians caring for their children may have led to understated or dishonest responses from parents. This point only adds to the power of the study, however, because the existing data likely underreport the true influence exerted by parents. Last, this study solely captures extrinsic pressure from parents. Numerous other parties, including coaches, siblings, and friends, likely contribute to the extrinsic pressure placed on young athletes to specialize in a single sport. This aspect was intentional, however, as the purpose of this study was to discretely and accurately evaluating parental impact. Future studies may contribute to comprehensively evaluating extrinsic influence.

In conclusion, parents both directly and indirectly contribute to youth specialization. Investments in personal and elite coaches are accompanied by elevated expectations of collegiate and professional play. Parents of specialized athletes more frequently endorsed significantly influencing their children’s specialization. As potentially harmful consequences of youth athlete specialization continue to be revealed, parents and coaches must astutely monitor athletes’ physical and psychosocial health while also evaluating their own personal influence. Physicians must broaden their evaluation of the youth athlete to include assessment of extrinsic pressures to best care for young athletes.

Appendix

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: C.S.A. is the head team physician for the New York Yankees, NYC FC, and is president of the MLB Team Physician Association.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Columbia University Medical Center.

References

- 1. Adirim TA, Cheng TL. Overview of injuries in the young athlete. Sports Med. 2003;33(1):75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmad CS, Padaki AS, Noticewala MS, Makhni EC, Popkin CA. The youth throwing score. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(2):317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amado D, Sanchez-Oliva D, Gonzelez-Ponce I, Pulido-Gonzalez JJ, Sanchez-Miguel PA. Incidence of parental support and pressure on their children’s motivational processes towards sport practice regarding gender. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Appleton PR, Hall HK, Hill AP. Examining the influence of the parent-initiated and coach-created motivational climates upon athletes’ perfectionistic cognitions. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(7):661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bell DR, Post EG, Trigsted SM, Hetzel S, McGuine TA, Brooks MA. Prevalence of sport specialization in high school athletics: a 1-year observational study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1469–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brenner JS; Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports specialization and intensive training in young athletes. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):2016–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bois JE, Lalanne J, Delforge C. The influence of parenting practices and parental pressures on children’s and adolescents’ pre-competitive anxiety. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(10):995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burt CW, Overpeck MD. Emergency visits for sports-related injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(3):301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan DK, Lonsdale C, Fung HH. Influences of coaches, parents, and peers on the motivational patterns of child and adolescent athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22(4):558–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feeley BT, Agel J, LaPrade RF. When is it too early for single sport specialization? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(1):234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gustafson SL, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Med 2006;36(1):79–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hall R, Barber Foss K, Hewett TE, Myer GD. Sport specialization’s association with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24(1):31–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Intensive training and sports specialization in young athletes. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1, pt 1):154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jayanthi NA, LaBella CR, Fischer D, Pasulka J, Dugas LR. Sports-specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kroshus E, Garnett B, Hawrilenko M, Baugh CM, Calzo JP. Concussion under-reporting and pressure from coaches, teammates, fans and parents. Soc Sci Med. 2015;134:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. LaPrade RF, Agel J, Baker J, et al. AOSSM early sport specialization consensus statement. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(4):2325967116644241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maatta S, Ray C, Roos E. Associations of parental influence and 10-11-year-old children’s physical activity: are they mediated by children’s perceived competence and attraction to physical activity? Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Makhni EC, Morrow ZS, Luchetti TJ, et al. Arm pain in youth baseball players: a survey of healthy players. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Myer GD, Jayanthi N, Difiori JP, et al. Sport specialization, part I: does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes? Sports Health. 2015;7(5):437–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sanchez-Miguel PA, Leo FM, Sanchez-Oliva D, Amado D, Garcia-Calvo T. The importance of parents’ behavior in their children’s enjoyment and amotivation in sports. J Hum Kinet. 2013;36:169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smucny M, Parikh SN, Pandya NK. Consequences of single sport specialization in the pediatric and adolescent athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46(2):249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valovich McLeod TC, Decoster LC, Loud KJ, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: prevention of pediatric overuse injuries. J Athl Train. 2011;46(2):206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zahra J, Sebire SJ, Jago R. “He’s probably more Mr. Sport than me”—a qualitative exploration of mothers’ perceptions of fathers’ role in their children’s physical activity. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]