Abstract

Introduction

Advanced melanoma is a devastating disease that has propelled therapeutics beyond chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Highly immunogenic, it has been the model tumor for immunotherapy and has highlighted the potential of the immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Areas covered

This review discusses the pharmacologic properties, clinical efficacy, and safety profile of pembrolizumab, an IgG4-kappa humanized monoclonal antibody against the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor, for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma.

Expert opinion

Pembrolizumab was the first PD-1 inhibitor to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Remarkably, this accelerated approval for the treatment of advanced, heavily pretreated melanoma was based on response rates alone from a phase I trial. As anticipated, pembrolizumab confirmed a survival advantage in phase II and III trials but faces stiff competition from other drugs that share its mechanism of action. Defining disease and patient characteristics associated with a response remains amongst the most pressing priorities.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint, melanoma, pembrolizumab, PD-1

1. Introduction

One in every three cancers diagnosed worldwide is a skin cancer.[1] While melanoma is the least common type of skin cancer, it is, by far, the most lethal. In a meta-analysis of 42 phase II trials that completed accrual between 1975 and 2005, the median survival time of patients with metastatic melanoma was 6.2 months, with only 25.5% of patients alive at 1 year.[2] Given melanoma’s resistance to traditional treatment approaches, there has been a low threshold for investigating novel therapies in these patients.

Unquestionably, melanoma has led the charge in immunotherapy. There is not only a sense of urgency that drives this research, but also practical and clinical considerations.[3, 4] From a practical standpoint, cutaneous melanomas are readily accessible for biopsy and easily adaptable to tissue culture.[5] From a clinical standpoint, the natural history of this disease can sometimes take a very atypical path, with clear evidence of the existence of antitumor immunity. Spontaneous regression of the primary lesion is not uncommon and has even been reported in metastatic lesions.[6] In fact, no primary tumor is found in about 3% of cases,[7] thought the genetic aberrations of these tumors are suggestive of a cutaneous origin.[8] Spontaneous or treatment-related vitiligo is also a well-recognized phenomenon, which corresponds to treatment response and prolonged survival.[9, 10] As one would expect from these observations, both primary tumors and metastases often have brisk lymphocytic infiltrates, a finding with its own important implications for prognosis.[11-13]

While melanoma exposes the potential of the immune system to recognize tumors, the disease also highlights fundamental challenges of garnering the immune system for cancer therapeutics. As a mutagen-induced malignancy, melanomas typically have thousands of mutations per exome, constituting one of the highest mutation frequencies of all cancers.[14] Decades have passed since a numerous melanoma tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) have been identified, classified, and targeted.[4, 15] Despite a favorable and well-studied antigenic profile, host responses alone, as well as vaccine strategies to enhance tumor antigen presentation, are insufficient to inhibit disease progression in most cases. Efforts to unravel this finding led to the discovery of immune checkpoint attenuation of T cell function. Since the first clinical application of immune checkpoint inhibitors as a complimentary therapy to vaccination,[16] patients with melanoma have been essential in unmasking the potential of this therapeutic strategy. This review will focus on pembrolizumab (formerly MK-3475 and lambrolizumab, trade name Keytruda), the first inhibitor of the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) pathway to obtain U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

2. Overview of the market

Between 2011 and FDA-approval of pembrolizumab on September 4th, 2014, the treatment of melanoma had undergone a transformation, with 5 drugs having receiving FDA approval.[17] These drugs included ipilimumab (2011), peginterferon alfa-2b (2011), vemurafenib (2011), dabrafenib (2013), and trametinib (2013). As an inhibitor of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) with impressive clinical responses, ipilimumab sparked a fervor for immune checkpoint blockade, while vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and trametinib highlighted the benefit of disrupting the B-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in patients with a V600E BRAF mutation. Meanwhile, Merck’s pembrolizumab and Bristol Myer-Squibb’s nivolumab, rival inhibitors of the PD-1 pathway, had been granted orphan drug designation, breakthrough therapy designation, and priority review for the treatment of advanced melanoma. At the time, it was widely anticipated that PD-1 inhibition would produce a less toxic, more robust response than CTLA-4 inhibition, given the prominent activity and broad expression of PD-1 in the tumor microenvironment, as opposed to within secondary lymphoid organs.[18] These features have been realized and have led to the development of many other PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors that have followed the two approved drugs into the clinical trial arena (Table 1).

Table 1.

Select Monoclonal Antibodies Targeting the PD-1 Pathway

| Agent | Alternative Name(s) | Developer | Phase in Melanoma | U.S. FDA Approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

PD-1

| ||||

| Pembrolizumab | MK-3475 | Merck | 3 | Melanoma |

| lambrolizumab | NSCLC | |||

|

| ||||

| Nivolumab | BMS-936558 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | 3 | Melanoma |

| ONO-4538 | NSCLC, RCC | |||

| MDX-1106 | Hodgkin Lymphoma | |||

|

| ||||

| MEDI0680 | AMP-514 | AztraZeneca | 1 | - |

|

| ||||

|

PD-L1

| ||||

| Atezolizumab | MPDL3280A | Roche | 2 | Urothelial |

| RG-7446 | carcinoma | |||

|

| ||||

| Avelumab | MSB0010718C | Merck KGAa-Pfizer | 2 | - |

|

| ||||

| Durvalumab | MEDI4736 | AztraZeneca | 2 | - |

|

| ||||

| BMS-936559 | Bristol-Myers Squibb | 1 | - | |

NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer; RCC: renal cell cancer

3. Introduction to the compound

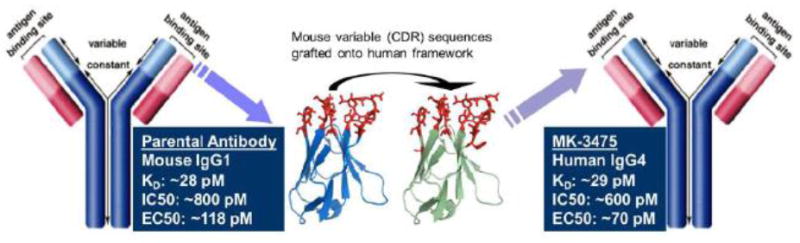

Pembrolizumab (molecular formula: C6504H10004N1716O2036S46; molecular weight: 146.3 kDa) is a highly selective, IgG4-kappa humanized monoclonal antibody against the PD-1 receptor. This agent was generated by grafting the variable region sequences of a very high affinity mouse antihuman PD-1 antibody onto a human IgG4-kappa isotype framework containing a stabilizing S228P Fc mutation (Figure 1).[19]

Figure 1.

Structure and derivation of the MK-3475 IgG4 framework from a murine IgG1 parental antibody as presented in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Pharmacology Review(s).[28] Image first appeared in Merck’s public presentation at the Pediatric ODAC on November 5, 2013.

IgG4 has become the preferred IgG subclass for immunotherapy because it only weakly induces complement and cell activation, owing to low affinity for C1q and Fc receptors.[20-22] A structural analysis of pembrolizumab has revealed a plausible explanation for this essential characteristic. Using X-ray crystallography, pembrolizumab has been shown to be a very compact molecule with an asymmetrical Y shape.[23] As compared to other IgG subclasses, the presence of a shorter and more compact hinge region imposes steric constraints that result in an unusual Fc structure. While the Fc domain is glycosylated at the CH2 domain on both chains, one CH2 domain is uniquely rotated 120° with respect to the conformation observed in all other reported structures, resulting in a more solvent accessible glycan chain. This conformation undoubtedly has biologic consequences, as Fc glycans play a myriad of crucial roles in maintaining and modulating effector functions.[24-26]

Not all features of IgG4 are beneficial for immunotherapy. Unlike the other subclasses, IgG4 has been found to participate in Fab-arm exchange, a process of exchanging half-molecules (one heavy chain/light chain pair) among themselves to form dynamic bispecific antibodies.[27] The instability of IgG4 introduces unpredictability to the clinical efficacy and toxicity of immunotherapies. Pembrolizumab overcomes this feature with the serine-to-proline replacement in position 228. This mutation has been shown to stabilize the interchain disulfide formation, preventing Fab-arm exchange.[23]

4. Pharmacodynamics

Pembrolizumab binds with high affinity (29 pM) to PD-1, antagonizing the interaction between PD-1 and its known ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration between 500 pM and 1 nM.[28] Engagement of PD-1 on T cells with PD-L1 or PD-L2 inhibits TCR-mediated T cell proliferation and cytokine production. Intracellularly, PD-1 activation inhibits CD28 signaling through the PI3K/AKT pathway, likely via the recruitment of the SHP-2 and SHP-1 phosphatases to the immune synapse, blocking the upregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-2 and IFNγ) and survival signals (e.g. Bcl-xl)[29, 30]. The inhibitory role of the PD-1 pathway has been shown to be essential in maintaining self-tolerance, minimizing collateral damage during physiologic responses to pathogens, and inducing maternal tolerance to fetal tissue[30-33]. By inhibiting this inhibitor in the treatment of cancer, pembrolizumab aims to shift the balance toward immune reactivity, enhancing tumor immunosurveillance and anti-tumor immune responses.

The pharmacodynamic activity of pembrolizumab was demonstrated in a staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB)-stimulated IL-2 assay using whole blood from both monkeys and humans.[28] SEB is known to enhance the surface expression PD-1 and PD-L1 in cultured lymphocytes in a time-dependent fashion. An approximately 2-4X increase in the production of IL-2 was observed when cultures of whole blood from monkeys or humans were incubated with SEB plus pembrolizumab, relative to cultures incubated with SEB alone. Additionally, pembrolizumab was evaluated in cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) derived from healthy volunteers that had been recently vaccinated with tetanus toxoid.[28] After cells were re-stimulated with tetanus toxoid in culture, there was a 2-5X increase in the amount of IFNγ produced in pembrolizumab-treated cultures, relative to control-treated cultures. This finding has raised concern that patients who are vaccinated or re-vaccinated while undergoing treatment with pembrolizumab may experience an enhanced immune response resulting in vaccine-associated toxicity.

Consistent with its IgG4 framework, pembrolizumab does not mediate effector functions, as assessed by binding to C1q and CD64 (surrogates for potential antibody dependent cell cytotoxicity activity).[28] Neither does it directly cause cytokine release, as demonstrated in a cytokine release assay that measured IL-2 production following culture of human PBMCs in pembrolizumab-immobilized (air-dried) plates.[28] Furthermore, its potential for immunogenicity appears to be negligible. In clinical studies in patients treated with pembrolizumab at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 or 3 weeks, 1 (0.3%) of 392 patients tested positive for treatment-emergent anti-pembrolizumab antibodies and were confirmed positive in the neutralizing assay.[34]

5. Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of pembrolizumab, readily accessible under the drug’s full prescribing information,[34] was studied in 2195 patients with advanced solid tumors who received doses of 1 to 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks or 2 to 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks. As an intravenously administered antibody, the drug is immediately and completely bioavailable and is not expected to bind to plasma proteins in a specific manner. Its volume of distribution at steady state is small (7.4 L; coefficient of variation [CV]: 19%), consistent with a limited extravascular distribution. Pembrolizumab undergoes catabolism to small peptides and single amnio acids via general protein degradation routes and does not rely on metabolism for clearance. Clearance increases with increasing body weight, explaining the rationale for dosing on a mg/kg basis. The geometric mean for clearance is 0.2 L/day (CV: 37%) and the terminal half-life is 27 days (CV: 38%). With repeat dosing every 3 weeks, steady-state concentrations are reached by 19 weeks and the systemic accumulation is 2.2-fold. On this schedule, exposure to pembrolizumab, as expressed by peak concentration (Cmax), trough concentration (Cmin), and area under the plasma concentration versus time curve at steady state (AUCSS), increases dose proportionally in the dose range of 2 to 10 mg/kg.

Pembrolizumab has been evaluated in special populations.[34] Age (range 15-94 years), gender, race, and tumor burden were found to have no clinically important effect on clearance. Patients with mild (GFR <90 and ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2; n=937) or moderate (GFR <60 and ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2; n=201) renal impairment have no clinically important difference in clearance compared to patients with normal renal function (GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2; n=1027). This is also true for patients with mild hepatic impairment (total bilirubin (TB) 1.0 to 1.5 × ULN or AST >ULN as defined using the National Cancer Institute criteria of hepatic dysfunction; n=269) compared to patients with normal hepatic function (TB and AST ≤ULN; n=1871). Pembrolizumab has not been studied in patients with severe (GFR <30 and ≥15 mL/min/1.73 m2) renal impairment or moderate (TB >1.5 to 3 x ULN and any AST) to severe (TB >3 x ULN and any AST) hepatic impairment. There is also no pharmacokinetic information on the drug in the pediatric population or in the case of overdosage.

6. Clinical efficacy

6.1 Phase I studies

The multicenter, open-label phase I clinical trial commonly referred to as KEYNOTE-001 (NCT01295827) provided preliminary evidence that pemprolizumab can produce a clinically meaningful response in patients with melanoma. KEYNOTE-001, which began enrolling patients with progressive, locally advanced, or metastatic carcinoma, melanoma, or non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) in March 2011, was designed to proceed in 6 parts over a span of almost 7 years.[35] Part A was not restricted to a specific patient population and involved dose-escalation to find the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and recommended Phase 2 dose. Part B and Part D restricted enrollment to patients with melanoma and tested various doses and schedules.

Results from the non-randomized Part B expansion cohort were reported by Hamid et al. in The New England Journal of Medicine.[36] A total of 135 patients received either the MTD, pembrolizumab every 2 weeks at a dose of 10 mg/kg, or pembrolizumab every 3 weeks at a dose of 2 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg. The confirmed overall response rate (ORR) across all doses was 38% by central review according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1) and 37% by the investigator according to immune-related response criteria (irRC). Response rates by RECIST ranged from 25% in the cohort that received 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks to 52% in the cohort that received 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks, but they did not vary according to prior exposure to ipilimumab. Remarkably, responses proved to be durable. The median duration of response had not been reached at a median follow-up time of 11 months, and 81% of the patients who had a response were still receiving the study treatment at the time of the analysis. The estimated median PFS was over 7 months, while the estimated median OS had not been reached.

Results from the randomized Part D expansion cohort were reported by Robert et al. in The Lancet.[37] Unlike the heterogeneous cohort in Part B (31% treatment-naïve, 64% ipilimumab-naïve, no requirement for prior treatment with BRAF or MEK inhibitors in BRAF-mutant disease), these 173 patients were required to be ipilimumab-refractory and BRAF/MEK inhibitor-refractory, making them a more homogeneous and heavily pretreated population. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1 final ratio) to pembrolizumab at 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks and were followed for a median duration of 8 months. ORR by RECIST was found to be 26% at both doses. Again, median duration of response was not reached in either group, and time from treatment initiation to response varied greatly, with most responses occurring by 12 weeks but some responses noted as late as 36 weeks. Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS at 6 months by RECIST were 45% in the 2 mg/kg group, 37% in the10 mg/kg groups, and 57% in either groups by irRC. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS at 1 year was 58% in the 2 mg/kg group and 63% in the 10 mg/kg group, revealing no significant difference between the groups (HR for the difference 1.09, 95% CI 0.68–1.75). As a result of these findings, on September 4, 2014 the U.S. FDA granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600 mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor.[17] Approval in the United Kingdom and European Union followed on March 10, 2015 and July 17, 2015, respectively.

6.2 Phase II studies

As a condition of the accelerated approval, Merck was required to conduct a confirmatory, multicenter, randomized trial establishing the superiority of pembrolizumab over standard therapy in patients with advanced melanoma. Both a phase II and phase III trial with co-primary endpoints of PFS and OS were already ongoing at the time of the announcement. KEYNOTE-002 (NCT01704287), which was opened in November 2012, was the name used to denote the phase II trial.[38] Patients enrolled in this trial had the same profile as those in KEYNOTE-001, Part D; their disease was unresectable or metastatic and refractory to ipilimumab and BRAF/MEK inhibitors, if BRAF-mutant positive. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive low-dose pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks), high-dose pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg every 3 weeks), or investigator-choice chemotherapy (paclitaxel plus carboplatin, paclitaxel, carboplatin, dacarbazine, or oral temozolomide). While individual treatment assignment between pembrolizumab and chemotherapy was open label, investigators and patients were masked to assignment of the dose of pembrolizumab. Participants on standard chemotherapy who experience disease progression were eligible to crossover to treatment with pembrolizumab.

Ribas et al. presented the PFS data obtained at the pre-specified second interim analysis in the intention-to-treat population.[39] Based on 410 progression-free survival events, PFS was improved in patients assigned to pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.45–0.73; P<0.0001) and pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg (HR,0.50; 95% CI, 0.39–0.64; P<0.0001) compared with those assigned to chemotherapy. PFS at 6 months was 34% (95% CI, 27–41) in the pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg group, 38% (95% CI, 31–45) in the 10 mg/kg group, and 16% (95% CI, 10–22) in the chemotherapy group. The separation between the PFS survival curves of the pembrolizumab arms and chemotherapy arm appeared to increase with time, with about a quarter of patients assigned to pembrolizumab (24% of 2 mg/kg group, 29% of 10 mg/kg group) progression free at 9 months compared with 8% assigned to chemotherapy. The superiority of both pembrolizumab doses was evident in all pre-specified patient subgroups and was amplified when investigators used irRC to assess response. At the time of data analysis, median duration of response was not reached in either pembrolizumab group (37 weeks in chemotherapy group), and OS data has not yet matured.

6.3 Phase III studies

The phase III trial in advanced melanoma, KEYNOTE-006 (NCT01866319), was opened in August 2013 and was designed to compare pembrolizumab and ipilimumab in patients who had not been exposed to any immune checkpoint inhibitor.[40] 834 patients, each having received no more than one previous systemic therapy, were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks, pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks, or ipilimumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 doses.

As reported by Robert et al.,[41] both pembrolizumab regimens significantly improved PFS and OS compared to ipilimumab and showed no difference in efficacy between each other. The estimated 6-month PFS rates were 47.3% for pembrolizumab every 2 weeks (HR for disease progression as compared with the ipilimumab group, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.72; P<0.0005), 46.4% for pembrolizumab every 3 weeks (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.72; P<0.0005), and 26.5% for ipilimumab. Estimated 12-month OS rates were 74.1% for pembrolizumab every 2 weeks (HR for death compared with the ipilimumab group, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.83; P = 0.0005), 68.4% for pembrolizumab every 3 weeks (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.90; P = 0.0036), and 58.2% for ipilimumab. About one-third of patients responded to pembrolizumab (ORR 33.7% of 2-week cohort, 32.9% of 3-week cohort), while about one-sixth of patients responded to ipilimumab (11.9%; P<0.001 for both comparisons). Responses were ongoing in 89.4%, 96.7%, and 87.9% of patients, respectively, after a median follow-up of 7.9 months.

Given these results, not only was the trial stopped early to allow patients in the ipilimumab group the option of receiving pembrolizumab, but also, on December 18, 2015, the U.S. FDA expanded the indication for pembrolizumab to include the initial treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma.[42] The authors of the paper highlighted 4 pressing questions for future trials: 1) the utility of tumor PD-L1 expression for response to pembrolizumab, 2) the most effective sequence of treatment for patients with BRAF v600 mutations, 3) the role of combination immunotherapy, 4) treatment of patients who have minimal disease progression or mixed responses.

7. Safety and tolerability

KEYNOTE-001 provided preliminary evidence that pembrolizumab is a safe and tolerable cancer therapy. Though a majority of patients (79%) in Part B reported at least one drug-related adverse event (AE), few patients (13%) experienced an AE of grade 3 or 4 severity.[36] Generalized symptoms predominated. AEs occurring in ≥20% of patients included fatigue, rash, pruritis, and diarrhea; those occurring in ≥10% of patients included nausea, myalgia, headache, asthenia, and elevated liver funtion tests (LFTs). A grade 1 infusion reaction occurred in 1 patient. The patients in Part D had a similar rate of any AE (82%) and grade 3-4 AEs (12%).[37] Importantly, the safety profiles between the pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg groups were found to be similar, which was confirmed in later trials and led to pooled analyses of summary safety results.[34] No drug-related deaths were reported in any melanoma patients in KEYNOTE-001.

AEs secondary to pembrolizumab led to interruption of the drug in 14% of patients and permanent discontinuation of the drug in 12% of patients in KEYNOTE-002.[39] These numbers were 21% and 9%, respectively, in KEYNOTE-006.[41] The most common adverse reactions, occurring in at least 20% of patients in either trial, were fatigue, rash, pruritis, constipation, nausea, diarrhea, and decreased appetite. Pembrolizumab was better tolerated than both chemotherapy and ipilimumab.[34] The incidence of grade 3-4 AEs ranged from 10% to 14% of patients in the pembrolizumab arms of either trial compared to 26% of patients in the chemotherapy arm and 20% of patients in the ipilimumab arm. AEs from pembrolizumab tended to occur later in treatment, required fewer treatment interruptions than chemotherapy, and fewer permanent discontinuations than ipilimumab. Given the mechanism of action of pembrolizumab, immune-mediated adverse events were given special attention (Table 2). Overall, they were encountered infrequently and were generally manageable with treatment interruption and corticosteroids.

Table 2.

Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions in Keynote-001, -002, and -006 (N=1567)

| Hypothyroidism | Hyperthyroidism | Pneumonitis | Colitis | Hepatitis | Nephritis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | 127 (8.1%) | 51 (3.3%) | 32 (2%) | 31 (2%) | 16 (1%) | 7 (0.4%) |

| Median time to onset | 3.3 months | 1.4 months | 4.3 months | 3.4 months | 26 days | 5.1 months |

| Median duration | 5.4 months | 1.7 months | 2.6 months | 1.4 months | 1.2 months | 1.1 months |

| No. (%)* of patients managed with steroids | - | - | 12 (38%) | 21 (68%) | 11 (69%) | 6 (86%) |

| No. (%)* of patients with symptom resolution | 24 (19%) | 36 (71%) | 21 (66%) | 27 (87%) | 14 (88%) | 4 (57%) |

| No. (%)* of patients requiring drug discontinuation | 0 | 2 (4%) | 9 (28%) | 14 (45%) | 6 (38%) | 2 (29%) |

Note: Adapted from KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) Full Prescribing Information [34]

Of patients diagnosed with the immune-mediated adverse reactions

8. Conclusion

The developmental programs of PD-1 pathway inhibitors were founded on the promising strategy of eradicating or containing cancer by removing immunosuppressive mechanisms supported by malignant cells at the level of the tumor microenvironment. Pembrolizumab meaningfully adds to biological plausibility with efficient and reliable pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic activity. Pembrolizumab entered the clinical arena at a time of significant changes in the treatment of advanced melanoma, as evident from U.S. FDA approval of 5 drugs within 3 years. Despite the recent advances in both targeted therapy and immumotherapy, the potential of pembrolizumab to contribute to the safe and effective treatment of patients with advanced melanoma was widely appreciated. Remarkably, pembrolizumab was granted accelerated approval based on a phase I trial demonstrating clinically meaningful, durable objective response rates in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600 mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. The drug successfully confirmed its efficacy in phase II and III trials and is now approved for the initial treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma, regardless of prior exposure to immune checkpoint inhibitors or BRAF V600 mutation status. Moving past melanoma, the model tumor for immunotherapy, pembrolizumab is now investigating its safety and efficacy in less immunogenic tumor types.

9. Expert Opinion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly those that target the PD-1 pathway, have captivated the medical community with properties characteristic of both passive and active immunotherapies. On the one hand, they are an exogenously-produced immune system component that do not rely on an intact immune system to induce immunological memory. On the other, they stimulate the host’s own immune system to mount an anti-tumor immune response, oftentimes producing a durable effect. Responses may be immediate or delayed. With increasing evidenced that immunosuppression is a particularly important component of the tumor microenvironment, they have played a major role in the recent paradigm shift in immunotherapeutics away from a focus on stimulating the immune system to a focus on inhibiting the inhibitors of an adequate immune response.

The U.S. FDA made a decisive statement on the therapeutic potential of pembrolizumab in the treatment of advanced, heavily pretreated melanoma by granting the drug accelerated approval based on response rates alone from a phase I trial. The importance of this decision cannot be understated, as typically the FDA requires evidence of improvement in OS, occasionally PFS. Even more remarkably, the response rates that led to FDA approval were obtained from a relatively short follow-up period, likely not capturing the full benefit of the drug. In total, 4 distinct patterns of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors have emerged: 1) timely regression of index lesions; 2) a slow but steady decline in tumor burden after stabilization of disease; 3) an initial increase in existing tumor burden followed by a delayed response; and 4) the appearance of new lesions followed by a delayed response.[43] The latter 3 patterns of response are not seen with traditional cytotoxic therapies and may be associated with improved immunooncologic outcomes.[44]

Pembrolizumab, however, faces stiff competition for selection by physicians. Nivolumab was able to demonstrate comparable safety and efficacy in a phase I trial that enrolled patients with advanced, heavily pretreated solid tumors, including patients with ipilimumab-refractory, BRAF-inhibitor-refractory melanoma.[45] As a result, nivolumab received accelerated approval by the FDA within 4 months of pembrolizumab’s accelerated approval for the same indication. PD-L1 inhibitors, such as Bristol-Myers Squibb’s BMS-936559, have also made strides in clinical trials, demonstrating complete or partial responses in a subset of patients.[46] Each drug has the opportunity to gain an edge over its competition by using clinical trials to better define when and how to administer the drug to achieve maximal results. Most importantly, biomarkers to predict responders must be developed to prevent costs from impeding their use.

Drug Summary Box.

|

| |

| Drug name (generic) | pembrolizumab |

|

| |

| Phase (for indication under discussion) | I (accelerated approval) |

| II (full approval) | |

| III (label update) | |

|

| |

| Indication (specific to discussion) | First-line treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma |

|

| |

| Mechanism of action | PD-1 inhibitor |

|

| |

| Route of administration | Intravenous |

|

| |

| Chemical structure | IgG4k humanized monoclonal antibody |

|

| |

| Pivotal trials | KEYNOTE-001 [35], -002 [38], -006 [40] |

|

| |

Acknowledgments

Funding

The research was supported by a National Cancer Institute T32 Training Grant awarded to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of California, Irvine.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

KS Tewari has served as a consultant for Genetech/Roche and that his institution has been awarded a research grant from Genentech for contracted research. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: [April 5 2016]. Skin cancers: how common is skin cancer? Ultraviolet radiation and the INTERSUN Programme. Available at: http://www.who.int/uv/faq/skincancer/en/index1.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, Chapman JA, Niedzwiecki D, Suman VJ, et al. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Feb 1;26(4):527–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haanen JB, et al. Immunotherapy of melanoma. EJC supplements : EJC : official journal of EORTC. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. 2013 Sep;11(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maio M. Melanoma as a model tumour for immuno-oncology. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2012 Sep;23(Suppl 8):viii10–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houghton AN, Gold JS, Blachere NE. Immunity against cancer: lessons learned from melanoma. Current opinion in immunology. 2001 Apr;13(2):134–40. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalialis LV, Drzewiecki KT, Klyver H. Spontaneous regression of metastases from melanoma: review of the literature. Melanoma research. 2009 Oct;19(5):275–82. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32832eabd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamposioras K, Pentheroudakis G, Pectasides D, Pavlidis N. Malignant melanoma of unknown primary site. To make the long story short. A systematic review of the literature. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2011 May;78(2):112–26. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakob JA, Bassett RL, Jr, Ng CS, Curry JL, Joseph RW, Alvarado GC, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2012 Aug 15;118(16):4014–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, Zwinderman AH, Reitsma JB, Spuls PI, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Mar 1;33(7):773–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrne KT, Turk MJ. New perspectives on the role of vitiligo in immune responses to melanoma. Oncotarget. 2011 Sep;2(9):684–94. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oble DA, Loewe R, Yu P, Mihm MC., Jr Focus on TILs: prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in human melanoma. Cancer immunity. 2009;9:3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussein MR. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and melanoma tumorigenesis: an insight. The British journal of dermatology. 2005 Jul;153(1):18–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erdag G, Schaefer JT, Smolkin ME, Deacon DH, Shea SM, Dengel LT, et al. Immunotype and immunohistologic characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells are associated with clinical outcome in metastatic melanoma. Cancer research. 2012 Mar 1;72(5):1070–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garraway LA, Lander ES. Lessons from the cancer genome. Cell. 2013 Mar 28;153(1):17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escors D. Tumour immunogenicity, antigen presentation and immunological barriers in cancer immunotherapy. New journal of science. 2014 Jan;5:2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/734515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodi FS, Mihm MC, Soiffer RJ, Haluska FG, Butler M, Seiden MV, et al. Biologic activity of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 antibody blockade in previously vaccinated metastatic melanoma and ovarian carcinoma patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003 Apr 15;100(8):4712–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830997100. ••The first clinical report of CTLA-4 antibody treatment of cancer patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FDA News Release. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Silver Spring, MD: [February 9 2016]. FDA approves Keytruda for advanced melanoma: first PD-1 blocking drug to receive agency approval. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm412802.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature reviews Cancer. 2012 Apr;12(4):252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patnaik A, Kang SP, Rasco D, Papadopoulos KP, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Beeram M, et al. Phase I Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475; Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody) in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015 Oct 1;21(19):4286–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2607. •Publication corresponding to the initial open-label, dose-escalation, expansion cohorts in the first-in-human phase I study to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors (KEYNOTE-001, Part A) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruhns P, Iannascoli B, England P, Mancardi DA, Fernandez N, Jorieux S, et al. Specificity and affinity of human Fcgamma receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood. 2009 Apr 16;113(16):3716–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferis R, Lund J. Interaction sites on human IgG-Fc for FcgammaR: current models. Immunology letters. 2002 Jun 3;82(1-2):57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radaev S, Sun P. Recognition of immunoglobulins by Fcgamma receptors. Molecular immunology. 2002 May;38(14):1073–83. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scapin G, Yang X, Prosise WW, McCoy M, Reichert P, Johnston JM, et al. Structure of full-length human anti-PD1 therapeutic IgG4 antibody pembrolizumab. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2015 Dec;22(12):953–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3129. •The first report of the crystallographic structure of a full-length IgG4 antibody. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Sim RB, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annual review of immunology. 2007;25:21–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lux A, Nimmerjahn F. Impact of differential glycosylation on IgG activity. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2011;780:113–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5632-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quast I, Lunemann JD. Fc glycan-modulated immunoglobulin G effector functions. Journal of clinical immunology. 2014 Jul;34(Suppl 1):S51–5. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Neut Kolfschoten M, Schuurman J, Losen M, Bleeker WK, Martinez-Martinez P, Vermeulen E, et al. Science. 5844. Vol. 317. New York, NY: 2007. Sep 14, Anti-inflammatory activity of human IgG4 antibodies by dynamic Fab arm exchange; pp. 1554–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pharmacology Review(s) U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Silver Spring, MD: [May 2 2016]. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Application Number: 125514Orig1s000. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/125514Orig1s000PharmR.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sathish JG, Johnson KG, Fuller KJ, LeRoy FG, Meyaard L, Sims MJ, et al. Constitutive association of SHP-1 with leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor-1 in human T cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2001 Feb 1;166(3):1763–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annual review of immunology. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunological reviews. 2008 Aug;224:166–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guleria I, Khosroshahi A, Ansari MJ, Habicht A, Azuma M, Yagita H, et al. A critical role for the programmed death ligand 1 in fetomaternal tolerance. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005 Jul 18;202(2):231–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Freeman GJ. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nature immunology. 2007 Mar;8(3):239–45. doi: 10.1038/ni1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp; Kenilworth, NJ: [May 2 2016]. KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) Prescribing Information. Available at: http://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/k/keytruda/keytruda_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.ClinicalTrialsgov. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: [April 12 2016]. Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in Participants With Progressive Locally Advanced or Metastatic Carcinoma, Melanoma, or Non-small Cell Lung Carcinoma (P07990/MK-3475-001/KEYNOTE-001) Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01295827. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Jul 11;369(2):134–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. ••Publication corresponding to KEYNOTE-001, Part B: the non-randomized expansion cohort of heterogeneous melanoma patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Hamid O, Kefford R, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014 Sep 20;384(9948):1109–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60958-2. ••Publication corresponding to KEYNOTE-001, Part D: the randomized expansion cohort of homogeneous melanoma patients that ultimately led to accelerated FDA approval of pembrolizumab in melanoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ClinicalTrialsgov. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: [April 12 2016]. Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) Versus Chemotherapy in Participants With Advanced Melanoma (P08719/KEYNOTE-002) Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01704287?term=KEYNOTE-002=1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Hamid O, Robert C, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2015 Aug;16(8):908–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2. ••Publication corresponding to KEYNOTE-002: the phase II study that confirmed the results of KEYNOTE-001, Part D, meeting the requirements of the accelerated approval. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ClinicalTrialsgov. U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: [April 12 2016]. Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Two Different Dosing Schedules of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) Compared to Ipilimumab in Participants With Advanced Melanoma (MK-3475-006/KEYNOTE-006) Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01866319?term=KEYNOTE-006=1. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2015 Jun 25;372(26):2521–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. ••Publication corresponding to KEYNOTE-006, the phase III study that enrolled melanoma patients not yet exposed to immune checkpoint inhibitors, which led to the label update in melanoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Approved Drugs. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Silver Spring, MD: [February 9 2016]. Pembrolizumab label updated with new clinical trial information. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm478493.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Weber JS, Allison JP, Urba WJ, Robert C, et al. Development of ipilimumab: a novel immunotherapeutic approach for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2013 Jul;1291:1–13. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbe C, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009 Dec 1;15(23):7412–20. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Jun 28;366(26):2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. ••The first report of a phase I study of a PD-1 inhibitor (nivolumab) in patients with advanced solid tumors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Jun 28;366(26):2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. ••The first report of a phase I study of a PD-L1 inhibitor (BMS-936559 in patients with advanced solid tumors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]