Abstract

A 56-year-old man with lymphoma developed orchitis followed by septic arthritis of his right glenohumeral joint. Synovial fluid cultures were negative but PCR amplification test was positive forUreaplasmaparvum. The patient was treated with doxycycline. Two and a half years later, the patient presented with shortness of breath and grade III/IV diastolic murmur on auscultation. Echocardiography revealed severely dilated left heart chambers, severe aortic regurgitation and several mobile masses on the aortic valve cusps suspected to be vegetations. He underwent valve replacement; valve tissue culture was negative but the 16S rRNA gene amplification test was positive for U. parvum.

He was treated again with doxycycline. In an outpatient follow-up 1 year and 3 months later, the patient was doing well. Repeated echocardiography showed normal aortic prosthesis function.

Background

Ureaplasma spp are known to cause epididymo-orchitis. Septic arthritis caused by Mycoplasmas and Ureaplasmas (members of the family Mycoplasmataceae) is very rare, but has been reported in immunosuppressed patients.1 Recent studies show that a vast majority of U. parvum isolates are susceptible to levofloxacin, tetracycline and macrolide antibiotics.2

Case presentation

A 56-year-old man was admitted on December 2015 with shortness of breath.

On April 2013, he had been diagnosed with primary central nervous system lymphoma and received chemoradiotherapy.

On June 2013, while being treated with chemotherapy, the patient was diagnosed with orchitis. A urine culture taken before antimicrobial treatment revealed mixed growth, representing contamination. He was treated empirically with ciprofloxacin for 10 days with clinical resolution of symptoms.

Ten days after completing antimicrobial treatment, he was diagnosed with septic arthritis of the right glenohumeral joint requiring hospitalisation. He had leucocytosis of 24,000/µL with 90% neutrophils and C reactive protein (CRP) of 197 mg/L. Arthroscopy was performed with evacuation of pus. Synovial fluid aspiration showed a leucocyte count of 108 ×109/l with 97% neutrophils and glucose of 2 mg/dL. Direct Gram stain, and synovial fluid and blood cultures were negative. A second arthroscopy 2 weeks later again showed negative Gram stain and culture. A 16S rRNA gene PCR amplification test from synovial fluid was positive with >99% identity for U. parvum. The patient was treated with ceftazidime and vancomycin empirically, followed by cefazolin and ciprofloxacin, altogether for 3 weeks with gradual improvement. After the diagnosis of U. parvum septic arthritis the patient was treated with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 6 weeks.

Two and a half years later, the patient was readmitted to our hospital due to shortness of breath. He was in complete remission since July 2013. He was afebrile, and physical examination was normal except for a grade III/IV diastolic heart murmur heard best on the left sternal border. The haemoglobin was 10.3 g/dL, CRP 7.4 mg/L (normal limits 0–5) and troponin I 0.118 ng/mL (normal limits 0–0.028). ECG revealed normal sinus rhythm. Enlarged heart silhouette and accentuated lung hili were noted on chest X-ray. Echocardiography was performed showing severe left atrial and ventricular enlargement, left ventricular ejection fraction of 55%, severe aortic regurgitation (AR) and several mobile masses on the aortic valve cusps (figure 1), with suspected perforation of the left leaflet. The severely dilated left heart chambers were suggestive of a long-standing valvular regurgitation. Blood cultures were negative. The patient was diagnosed with culture-negative endocarditis (CNE) and investigated considering the local epidemiology of CNE in Israel. Q fever indirect fluorescence assay and Bartonella henselae ELISA serology tests, were negative. The patient underwent aortic valve replacement surgery for symptomatic severe AR 7 days after admission. Findings on surgery included a ruptured leaflet and several vegetations. Valve pathology yielded calcifications and paucity of lymphocytes. Valve tissue culture was negative but the 16S rRNA PCR gene amplification test from the valve was positive for U. parvum.

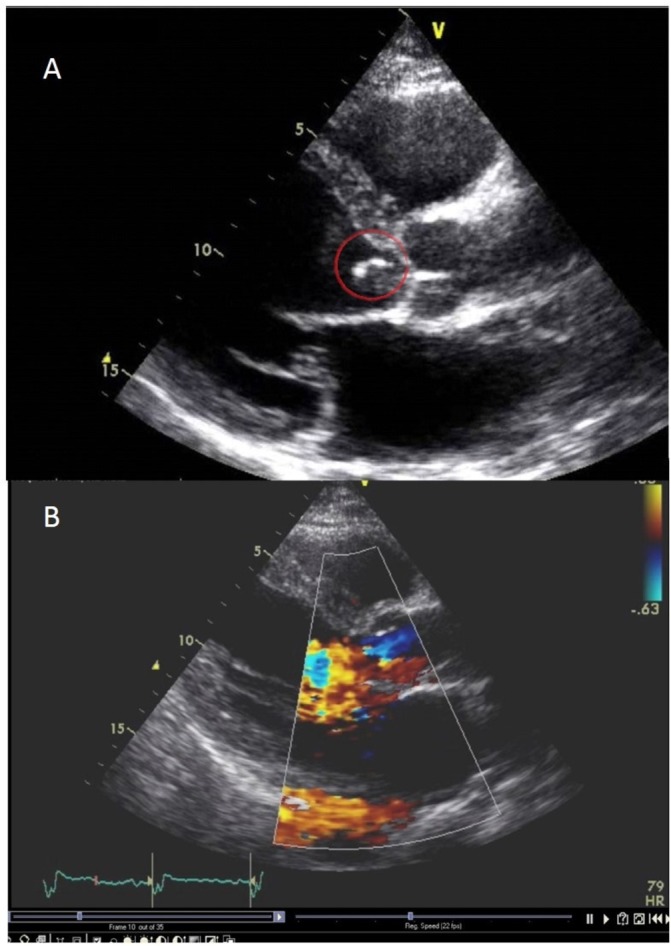

Figure 1.

Severe left atrial and ventricular enlargement, mobile mass on the aortic valve cusp (A); severe aortic regurgitation (B).

Investigations

For molecular identification, DNA was extracted from the sample using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). Broad-range 16S ribosomal RNA gene was performed using two sets of primers.3 4 PCR products were separated by electrophoresis, sequenced using the 3130 genetic analyser capillary electrophoresis DNA sequencer and analysed using a basic local alignment search tool.

Efforts to isolate the pathogen from valve tissue culture including seeding on blood, chocolate and chromogenic plates in our local microbiology laboratory were unsuccessfull. We further sent the valve tissue specimen to a referral laboratory (Unité de Recherche sur les Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales Émergentes, Marseille, France). Valve cultures were negative in both laboratories.

Differential diagnosis

We debated whether his final presentation represented active endocarditis or whether it was the consequence of progressive degenerative changes following undiagnosed endocarditis that developed during or early after the septic arthritis episode. The latter assumption was supported by absence of fever and the paucity of inflammation on excised valve. Persistence of bacterial DNA on valve tissue for years following an episode of infective endocarditis (IE) has been described in Bartonella spp5 and Coxiella burnetii endocarditis,6 a finding that does not correspond necessarily with persistence of viable bacteria. On the other hand, the unexplained and severe AR with preoperative echocardiography and intraoperative findings were highly suggestive of active endocarditis.

Treatment

After the valve replacement, we recommended doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 6 months with no evidence to guide the optimal treatment duration. No adverse events were observed throughout the treatment, but the effect of treatment on selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria was not monitored.

Outcome and follow-up

On follow-up 1 year and 3 months later, the patient was doing well. Repeated echocardiography showed normal aortic prosthesis function.

Discussion

Eight previous cases of endocarditis caused by mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas in adults have been reported (table 1).

Table 1.

Nine cases of infective endocarditis caused by Mycoplasmataceae

| Patient (reference) |

Age, sex | Underlying condition(s) | Valve(s) | Symptom(s) | Diagnostic tool | Pathogen | Surgery | Antibiotic therapy (duration, weeks) | Outcome |

| 1 7 |

33, M | Mitral valve plasty | Mitral | Heart failure | PCR from cardiac valve | M. hominis | Y | Amo and genta (3); Doxy (4) | Survival |

| 2 7 |

57, F | Prosthetic aortic valve | Aortic | Heart failure | PCR from cardiac valve | U. urealyticum | Y | Vanco (8); Genta (2) | Death |

| 3 9 |

21, M | RHD; dental extraction without antibiotic prophylaxis 4 weeks before hospitalisation | Mitral | Fever, anorexia, sore throat, malaise | Serology | M. pneumoniae | N | Benz and genta (6); Oxy (4) | Survival |

| 4 10 |

25, F | SLE treated with corticosteroids; Streptococcus sanguis endocarditis; prosthetic aortic and mitral valves | Aortic and mitral | Fever | Culture from a portion of valve | M. hominis | Y | Clin and rif (6); Doxy (4) |

Survival |

| 5 11 |

40, M | RHD, aortic and mitral replacement | Aortic and mitral | Abdominal pain, jaundice, fever | 16S rDNA PCR, culture | M. hominis | Y | Doxy and clin (8) | Survival |

| 6 12 |

74, M | Aortic and mitral valve replacement | Aortic | Dizziness, cardiac and kidney failure | 16S rDNA PCR, culture | M. hominis | Y | Doxy and clin (9) | Survival |

| 7 13 |

57, M | Aortic valve replacement, aortic root and mitral repair | Aortic | Dyspnoea, fatigue, chest pain | 16S rDNA PCR | M. hominis | Y | Doxy and clin (9) | Survival |

| 8 8 |

46, M | Mitral valve replacement | Mitral | Dyspnoea, heart failure | Culture | M. hominis | Y | Vanco and amika | Death |

| 9 (PR) |

56, M | s/p lymphoma, s/p septic arthritis with U. parvum | Aortic | Dyspnoea, heart failure | PCR from cardiac valve | U. parvum | Y | Doxy (8) | Survival (15 months after surgery) |

Amika, amikacin, Amo, amoxicillin, Benz, benzylpenicillin, Clin, clindamycin, Doxy, doxycycline, Genta, gentamicin, Oxy, oxytetracycline, PR, present report, RHD, rheumatic heart disease, Rif, rifampin, SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus, s/p, status post, Vanco, vancomycin

All patients that were treated with tetracycline (n=6) survived, while two patients that did not receive antimicrobial therapy eventually died.7 8 Treatment duration was 4 weeks in three cases and 8–9 weeks in three. The prolonged antibiotic course we recommended after valve replacement is not evidence-based and is based on personal opinion considering the chronic course of the disease and the transplanted biological valve.

We present this case to highlight the importance of nucleic acid-based tests in the investigation of infections of unknown aetiology, including CNE. Physicians should be aware of the fact that ureaplasma infection can cause severe complications in immunosuppressed patients. Close monitoring and follow-up in cases with intracellular invasive infections may lead to early diagnosis of possibly severe complications.

Learning points.

Immunosuppressed patients have unusual infections caused by common or uncommon pathogens.

There is an important role for nucleic acid-based tests in diagnosis of infections caused by intracellular pathogens.

Mycoplasmataceae can also cause infective endocarditis with an insidious course.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design of case report: MP, AK, RN, NG-Z, AN. Acquisition of data: AK, RN, YG. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: MP, AK, RN, NG-Z.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Furr PM, Taylor-Robinson D, Webster AD. Mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas in patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia and their role in arthritis: microbiological observations over twenty years. Ann Rheum Dis 1994;53:183–7. 10.1136/ard.53.3.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández J, Karau MJ, Cunningham SA, et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Clonality of Clinical Ureaplasma Isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016;60:4793–8. 10.1128/AAC.00671-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harmsen D, Dostal S, Roth A, et al. RIDOM: comprehensive and public sequence database for identification of Mycobacterium species. BMC Infect Dis 2003;3:26 10.1186/1471-2334-3-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothman RE, Majmudar MD, Kelen GD, et al. Detection of bacteremia in emergency department patients at risk for infective endocarditis using universal 16S rRNA primers in a decontaminated polymerase chain reaction assay. J Infect Dis 2002;186:1677–81. 10.1086/345367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rovery C, Greub G, Lepidi H, et al. PCR detection of bacteria on cardiac valves of patients with treated bacterial endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:163–7. 10.1128/JCM.43.1.163-167.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edouard S, Million M, Lepidi H, et al. Persistence of DNA in a cured patient and positive culture in cases with low antibody levels bring into question diagnosis of Q fever endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:3012–7. 10.1128/JCM.00812-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenollar F, Gauduchon V, Casalta JP, et al. Mycoplasma endocarditis: two case reports and a review. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:e21–e24. 10.1086/380839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasco M, Torres L, Marco ML, et al. Prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Mycoplasma hominis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000;19:638–40. 10.1007/s100960000333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popat K, Barnardo D, Webb-Peploe M. Mycoplasma pneumoniae endocarditis. Br Heart J 1980;44:111–2. 10.1136/hrt.44.1.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen JI, Sloss LJ, Kundsin R, et al. Prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Mycoplasma hominis. Am J Med 1989;86(6 Pt 2):819–21. 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90479-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamil HA, Sandoe JA, Gascoyne-Binzi D, et al. Late-onset prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Mycoplasma hominis, diagnosed using broad-range bacterial PCR. J Med Microbiol 2012;61(Pt 2):300–1. 10.1099/jmm.0.030635-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagneux-Brunon A, Grattard F, Morel J, et al. Mycoplasma hominis, a Rare but True Cause of Infective Endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53:3068–71. 10.1128/JCM.00827-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain ST, Gordon SM, Tan CD, et al. Mycoplasma hominis prosthetic valve endocarditis: the value of molecular sequencing in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:e7–e9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]