Abstract

Engineering vascularized tissue constructs and organoids has been historically challenging. Here we describe a novel method based on microfluidic bioprinting to generate a scaffold with multilayer interlacing hydrogel microfibers. To achieve smooth bioprinting, a core-sheath microfluidic printhead containing a composite bioink formulation extruded from the core flow and the crosslinking solution carried by the sheath flow, was designed and fitted onto the bioprinter. By blending gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) with alginate, a polysaccharide that undergoes instantaneous ionic crosslinking in the presence of select divalent ions, followed by a secondary photocrosslinking of the GelMA component to achieve permanent stabilization, a microfibrous scaffold could be obtained using this bioprinting strategy. Importantly, the endothelial cells encapsulated inside the bioprinted microfibers can form the lumen-like structures resembling the vasculature over the course of culture for 16 days. The endothelialized microfibrous scaffold may be further used as a vascular bed to construct a vascularized tissue through subsequent seeding of the secondary cell type into the interstitial space of the microfibers. Microfluidic bioprinting provides a generalized strategy in convenient engineering of vascularized tissues at high fidelity.

Keywords: Bioengineering, Issue 126, Bioprinting, tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, organoids, organ-on-chip, vascularization, endothelialization, microfibers

Introduction

Tissue engineering targets to generate functional tissue substitutes that can be used to replace, restore, or augment those injured or diseased in the human body1,2,3,4, often through a combination of desired cell types, bioactive molecules5,6, and biomaterials7,8,9,10. More recently, tissue engineering technologies have also been increasingly adopted to generate in vitro tissue and organ models that mimic the important functions of their in vivo counterparts, for applications such as drug development, in replacement of the conventional over-simplified planar cell cultures11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In both situations, the ability to recapitulate the complex microarchitecture and hierarchical structure of the human tissues is critical in enabling functionality of the engineered tissues10, and in particular, ways to integrate a vascular network into the engineered tissues are of demand since vascularization presents one of the greatest challenges to the field20,21,22,23.

To date, a variety of approaches have been developed in this regard in an attempt to build blood vessel structures into engineered tissue constructs with various degrees of success8. For example, self-assembly of endothelial cells allows for generation of microvascular networks24; delivery of angiogenic growth factors induces sustained neovascularization25,26; use of vascular progenitor cells and pericytes facilitates endothelial cell growth and assembly24,27; designing scaffold properties enables precise modulation of vascularization28,29; and cell sheet technology allows for convenient manipulation of vascular layering30. Nevertheless, these strategies do not endow the capability of controlling the spatial patterning of the vasculature, often leading to random distribution of blood vessels within an engineered tissue construct and thus limited reproducibility. During the past few years bioprinting has emerged as a class of enabling technologies towards the solution of such a challenge, due to their unparalleled versatility of depositing complex tissue patterns at high fidelity and reproducibility in an automated or semi-automated manner31,32,33. Sacrificial bioprinting34,35,36,37,38, embedded bioprinting39,40,41, and hollow structure bioprinting/biofabrication42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 have all demonstrated the feasibility of generating vascular or vascularized tissues.

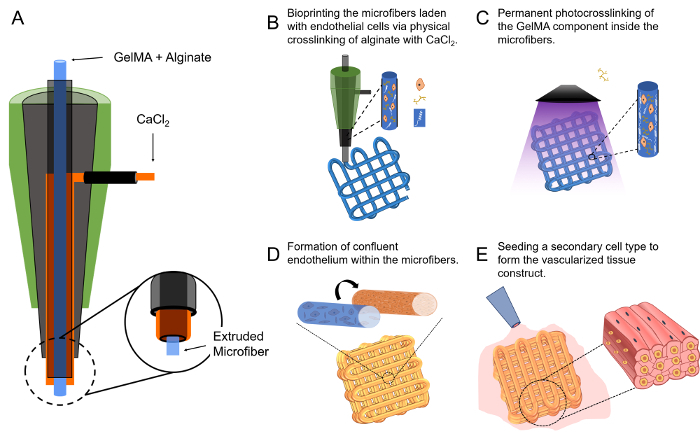

Alternatively, a microfluidic bioprinting strategy to fabricate microfibrous scaffolds have been recently developed, where a hybrid bioink composed of alginate and gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) was delivered through the core of a concentric printhead and a calcium chloride (CaCl2) solution was carried through the outer sheath flow of the printhead54,55. The co-extrusion of the two flows allowed for immediate physical crosslinking of the alginate component to enable microfiber formation, while subsequent photocrosslinking ensured permanent stabilization of the multi-layer microfibrous scaffold. Of note, endothelial cells encapsulated within the bioprinted microfibers were found to proliferate and migrate towards the peripheries of the microfibers assuming lumen-like structures that mimicked the vascular bed54,55. These bioprinted, endothelialized vascular beds could be subsequently populated with desired secondary cell types to further construct vascularized tissues55. This protocol thus provides a detailed procedure of such a microfluidic bioprinting strategy enabled by the concentric nozzle design, which ensures convenient fabrication of vascularized tissues for potential applications in both tissue engineering and organoid modeling.

Protocol

The neonatal rat cardiomyocytes used in this protocol were isolated from 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats following a well-established procedure56 approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Brigham and Women's Hospital.

1. Instrumentation of the Bioprinter

Insert a smaller blunt needle (e.g., 27G, 1 inch) as the core into the center of a larger blunt needle (e.g., 18G, ½ inch) as the sheath to construct the dual-layer, concentric microfluidic printhead; make sure that the core needle is protruding slightly (~1 mm) longer than the outer shell (Figure 1A). The alignment is usually adjusted manually, but if necessary spacers of proper sizes can be temporally sandwiched in between the inner/outer needles at both the tip and the barrel sides to assist concentric alignment. Seal the junction of the barrels with epoxy glue and remove the alignment spacers from the tip side when applicable.

Insert another needle (23G) in the barrel of the central needle in the reverse direction. Then generate a hole on the side of the barrel of the outer needle and insert a metal connector of matching size into the hole, followed by sealing with epoxy glue.

Connect the inlets of the printhead to a dual-channel syringe pump for injection of the bioink and the crosslinking solution, individually, through two PVC tubes. Mount the extruder onto the head of a bioprinter using a plastic holder made of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). NOTE: Bioprinter selection depends on availability. In our case, we have successfully tested this setup on several commercially available bioprinters. However, any bioprinter that features an x-y-z motorized stage should, in principle, enable integration of this microfluidic printhead.

2. Bioprinting the Microfibrous Vascular Bed

Make the bioink using a mixture of alginate (4 w/v%, low viscosity), gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA, 1-2 w/v%)57,58, and photoinitiator Irgacure 2959 (0.2 - 0.5 wt.%) dissolved in 25 mM 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazin-1-yl] ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES buffer, pH 7.4) containing 10 vol.% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Make a solution of 0.3-M CaCl2 in HEPES buffer containing 10 vol.% FBS as the crosslinking carrier fluid.

Immediately before bioprinting, dissociate human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) from the flasks using treatment by 0.05 w/v% trypsin for 5 - 10 min, and resuspend the cells in the bioink at a concentration of 5 - 10 × 106 cells/mL. Pipette the suspension slowly 5 to 10 times to ensure homogenous distribution.

Start the injection of the bioink/crosslinking fluid using a dual-channel syringe pump at the same flow rates of 5 µL/mL. The flows can be allowed to continuously run for up to 1 min until they stabilize. Subsequently, initiate the movement of the printhead by controlling the bioprinter at a deposition speed of approximately 4 mm/s (Figure 1B). These speeds may need fine tuning with each new setup to ensure optimal bioprinting. The bioprinting process is usually conducted at room temperature (21 - 25 °C) but this temperature may be altered. The bioprinting process should allow for fast ionic gelation of the alginate component and deposition of a microfibrous scaffold (Figure 1B).

After the scaffold is bioprinted, achieve chemical gelation by further photocrosslinking the GelMA component, at approximately 5 - 10 mW/cm2 of UV light (360 - 480 nm) for 20 - 30 s (Figure 1C).

Following the bioprinting and crosslinking, gently rinse the scaffold with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the excess CaCl2. Culture the HUVECs-laden microfibrous scaffold in endothelial cell growth medium (EGM) in an incubator at 37 °C and 5 vol.% CO2 for up to 16 days with medium changed at least every 2 days. Monitor the morphologies of the HUVECs under a microscope during the culture period.

3. Constructing the Vascularized Tissues

Once the HUVECs have migrated to the peripheries of the microfibers in the scaffold to form the lumen-like structures (Figure 1D), retrieve the scaffold and gently place it on the surface of a hydrophobic surface (e.g., a slab of polymethylsiloxane [PDMS]). Use a piece of sterile filter paper to carefully remove all the medium from the interstitial space of the scaffold with capillary force.

Immediately add a drop (approximately 20 - 40 µL) of suspension of a secondary cell type (e.g., cardiomyocytes) in medium at a density of 1 - 10 × 106 cells/mL on top of the scaffold, which should infiltrate the entire interstitial space of the scaffold (Figure 1E). Incubate such a configuration in an incubator (37 °C, 5 vol.% CO2, 95% relative humidity) for 0.5 - 2 h to allow the cells to adhere onto the individual microfibers. Monitor the droplet size over the period to ensure that no noticeable evaporation is observed.

Gently wash the scaffolds by shaking in a PBS bath to remove any non-adherent cells and culture the construct in relevant medium until the desired vascularized tissue is formed.

Representative Results

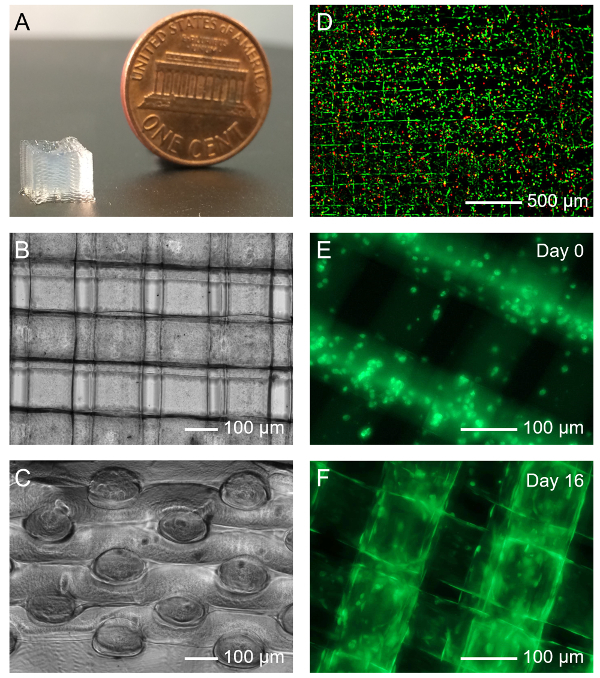

The microfluidic bioprinting strategy allows for direct extrusion bioprinting of microfibrous scaffolds using low-viscosity bioinks54,55. As illustrated in Figure 2A, a scaffold with a size of 6 × 6 × 6 mm3 containing >30 layers of microfibers could be bioprinted within 10 min. The immediate ionic crosslinking of the alginate component with CaCl2 allowed for excellent structural integrity during the bioprinting process while the subsequent physical photocrosslinking of the GelMA component ensured long-term stability of the bioprinted microfibrous scaffold, as indicated in top view and side view shown in Figures 2B and 2C. The microfibers achieved in this case, under the bioprinting conditions specified in the protocol, were approximately 100 - 150 µm in diameter, which would slightly increase overtime with swelling.

The bioprinting process, including the microfluidic extrusion of the bioink, the ionic crosslinking, and the photocrosslinking, did not significantly affect the viability of the encapsulated HUVECs. The cells could maintain a relatively high viability of >80% after completion of all these procedures (Figure 2D). As reported earlier54,55, the HUVECs could gradually proliferate and migrate in the microfibers from the initially random distribution at Day 0 (Figure 2E) to the peripheries of the microfibers to assume lumen-like structures at Day 16 post-bioprinting in culture (Figure 2F). Such a behavior observed for the HUVECs was likely due to the intrinsic interface-driven tendency of the endothelial cells as well as the higher availability of nutrients and oxygen surrounding the microfibers than in their interiors55,59.

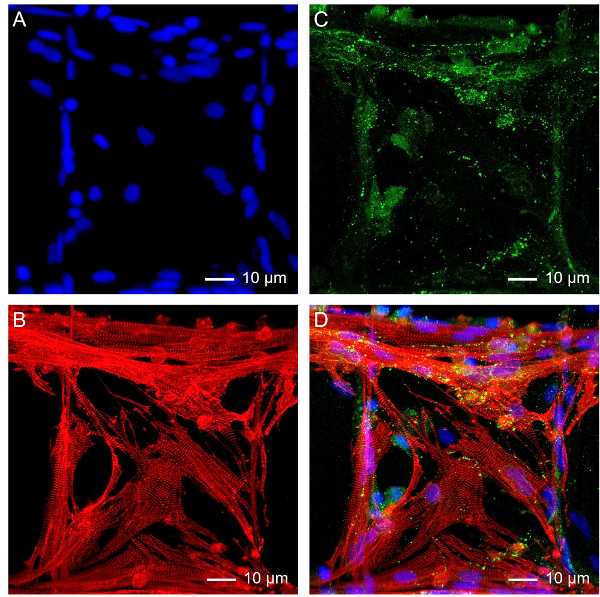

The microfibrous scaffold can also function as a standalone platform for tissue engineering. Using myocardium tissue as an example, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were seeded onto the interstitial space of a bioprinted scaffold at a density of 5 × 106 cells/mL, and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 vol.% FBS. The medium was changed every day in the first 2 - 3 days until the cardiomyocytes started beating, after which only ½ medium was exchanged every 2 - 3 days55,60,61,62. The cells could maintain their spontaneous and synchronized beating for up to 9-28 days depending on the cell source and configuration of the scaffolds55. The mature cardiomyocytes on the scaffold also showed strong expression of functional cardiac biomarkers as illustrated in the confocal fluorescence images in Figure 3, including sarcomeric α-actinin (Figure 3B) and connexin-43 (Figure 3C).

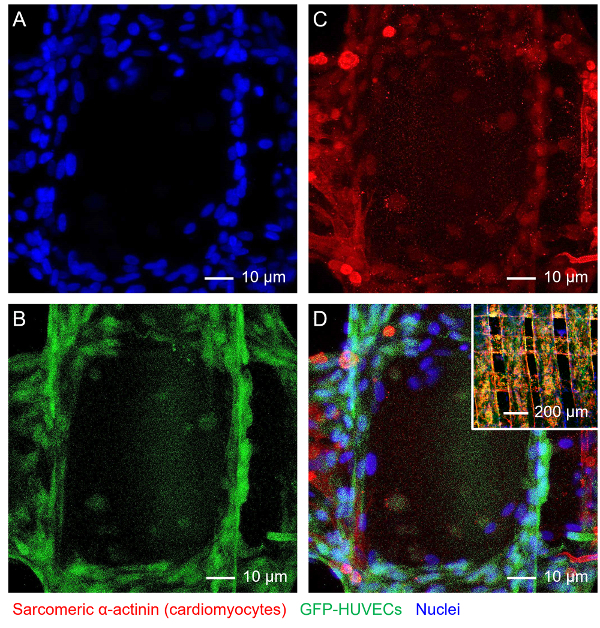

Combining the endothelial cells and the secondary cell type, a vascularized tissue could be further constructed. Again, using myocardium as an example, after the vascular bed has formed in a bioprinted microfibrous scaffold after roughly 16 days of culture, neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were subsequently seeded into the interstitial space of the scaffold. After culturing and maturation in a common medium composed of 1:1 volume ration of EGM:DMDM, an endothelialized myocardial tissue could be formed exhibiting spontaneous and synchronous beating55. Single-plane confocal fluorescence images in Figure 4 further revealed co-existence of both cell types, with the HUVECs mainly present in the boundaries of the microfibers (Figure 4B) and the cardiomyocytes surrounding the exteriors of the microfibers (Figure 4C).

Figure 1: The Microfluidic Bioprinting Strategy for Generating Vascularized Tissue Constructs. (A)The design of the core-sheath coaxial printhead for co-extrusion of the composite bioink and the CaCl2. (B-E) Schematics showing the fabrication procedure of a vascularized tissue construct. This figure has been modified with permission from Ref.55. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Bioprinting the Microfibrous Vascular Bed. (A) Photograph showing a bioprinted 30-layer microfibrous scaffold. (B, C) Top and side views of micrographs showing a bioprinted scaffold. (D) Viability of HUVECs laden in a bioprinted microfibrous scaffold. Green and red indicate live and dead cells, respectively. (E, F) Fluorescence micrographs showing the organization of green fuorescent protein (GFP)-HUVECs in the bioprinted microfibers at Day 0 and Day 16 post bioprinting, respectively. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Subsequent Growth of Cardiomyocytes on the Bioprinted Microfibrous Scaffold. Fluorescence micrographs showing (A) nuclei, (B) sarcomeric α-actinin, (C) connexin-43, and (D) superimposition. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Construction of Endothelialized Myocardial Tissue. Fluorescence micrographs showing (A) nuclei, (B) GFP-HUVECs, (C) f-actin of both HUVECs and cardiomyocytes, and (D) superimposition. Inset in D shows a lower-magnification image of the endothelialized myocardial tissue. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Supplementary Dataset. A sample G-code file for bioprinting a 6 × 6 mm2 square lattice with 220 µm spacing between adjacent microfibers.

Discussion

Construction of the co-axial printhead represents a critical step towards successful microfluidic bioprinting to allow for simultaneous delivery of both the bioink from the core and the crosslinking agent from the sheath. While in this protocol an example printhead was created using a 27G needle as the core and an 18G needle as the shell, it may be readily extended to a variety of combinations using different sizes of needles. However, the alteration in the needle sizes, which results in the change in the amount of flow delivered in each phase, will require further optimization of the flow rates of both the bioink and the crosslinking agent (individually adjustable using two syringe pumps instead of a dual-channel one), and potentially also the deposition speed incurred by the bioprinter.

The combination of the parameters (needle sizes, flow rates, and deposition speed) in the current protocol led to the bioprinted microfibers with a diameter of approximately 120 µm immediately after deposition, which would swell to roughly 150 µm after equilibration in medium55. Such a size also roughly equals to the layer thickness of the bioprinted constructs as there was no space between the layers of the microfibers. The diameter of the bioprinted microfibers is a function of all three parameters54,63; the size of the core needle of the printhead and the flow rate of the bioink are positively correlated with the diameter of the microfibers, whereas the size of the sheath needle, the flow rate of the crosslinking agent, and the deposition speed are negatively correlated with the diameter of the microfibers. The control over the movement of the printhead and/or the motorized stage would allow for deposition of microfibrous scaffolds of arbitrary structures54,55.

Furthermore, the formulation of the bioink may change the profile of the bioprinting as well. For example, the amount of alginate and GelMA can be slightly modulated according to specific applications, and it is possible to blend additional materials into the bioink, such as polyethylene glycol-tetraacrylate (PEGTA) that increases the mechanics of the bioprinted microfibers40. The UV crosslinking also determines the mechanical properties of the center of the bioprinted microfibers, which can further affect the behavior of the embedded endothelial cells54. The parameters reported in this protocol was optimized for HUVECs. However, it is anticipated that, for each different type of endothelial cells the crosslinking parameters will need to be re-optimized to achieve lumen formation in the microfibers.

To seed a secondary cell type onto the bioprinted vascular bed, it is necessary to place the scaffold onto a piece of hydrophobic surface and ensure that most medium in the interstitial space of the scaffold is removed. This will allow immediate infiltration of the cell suspension into the microfibrous structure with the droplet free-standing and encapsulating the scaffold during the course of seeding, maximizing the number of cells attached onto the surface of the microfibers. Although a relatively high density of cardiomyocytes at 5 × 106 cells/mL was used for constructing the myocardial tissue in the current protocol, such density can be arbitrarily tuned to match specific tissue types. It is also critical to maintain a humidified environment, which can be realized by filling sterile water or PBS in the vicinity of the scaffold (i.e., in the surrounding wells or the space surrounding the PDMS slab), ensuring that the small amount of medium for seeding does not evaporate over the period of seeding.

In summary, we have provided a detailed protocol of microfluidic bioprinting for convenient fabrication of vascularized tissues. In this strategy, a core-sheath co-axial printhead is used to enable simultaneous extrusion of a hybrid bioink from the core and crosslinking agent from the sheath. Upon co-extrusion, the bioink immediately undergoes physical crosslinking for its alginate component forming a layered microfibrous scaffold as programmed by the movement of the bioprinter, while the entire construct is further chemically photocrosslinked for the GelMA component to allow long-term stability. Endothelial cells encapsulated in the microfibers during the bioprinting process can proliferate and migrate to the peripheries assuming lumen-like structures, turning the scaffold into a vascular bed. By seeding a secondary cell type, a vascularized tissue construct can be subsequently generated. This microfluidic bioprinting strategy is unique, and can be conveniently extended to a variety of tissue types such as liver, skeletal muscle, and cancers besides the myocardium illustrated in the current protocol, by rational combination of desired cell types and specially designed patterns of the bioprinted microfibrous scaffolds. The vascularized tissue constructs produced with such a method may be used for in vivo tissue regeneration or for in vitro tissue modeling.

There are several limitations associated with the microfluidic bioprinting strategy described in this protocol. First, the diameter of the bioprinted microfibers is limited to a few hundred micrometers due to the diffusion barrier of the hydrogel matrix for the CaCl2 solution to efficiently crosslink the alginate component in the core. Overly low physical crosslinking density would make the multilayer structure unstable. Second, the physical crosslinking agent of CaCl2 solution may exert negative effects on certain endothelial cell types that are more fragile than HUVECs, such as the endothelial progenitor cells. The feasibility of using such a bioprinting method for a wider variety of endothelial cell types may require additional investigations. Third, while the endothelial cells can form lumen-like structures within the microfibers, the cores of these microfibers are not hollow to enable perfusion. Therefore, nutrients and oxygen are still provided mainly through the interstitial space in the bioprinted scaffolds. The adaptation of sacrificial materials as the photocrosslinkable component of the bioink64 may solve this issue in future versions of the technology. Alternatively, bioprinted hollow microfibrous structures42,43,65,66,67,68 may be used as the vascular bed to ensure direct perfusion of the vascularized tissue constructs. Last, bioprinting of clinical-sized tissues may still be challenging, which can likely be addressed by incorporating design of arrayed microfluidic printheads69 to achieve expanded-scale bioprinting at high throughput.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence Award (K99CA201603).

References

- Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue Engineering. Science. 1993;260(5110):920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Progress in Tissue Engineering. Sci. Am. 2009;300(5):64–71. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0509-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R. Tissue Engineering: Status and Challenges. E-Biomed: J.Regen. Med. 2004;1(1):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Atala A, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Engineering Complex Tissues. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4(160):112. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi M, Ungaro F, Quaglia F, Netti PA. Controlled Drug Delivery in Tissue Engineering. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2008;60(2):229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayalia P, Mooney DJ. Controlled Growth Factor Delivery for Tissue Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2009;21(32-33):3269–3285. doi: 10.1002/adma.200900241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell JA. Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 1995;13(6):565–576. doi: 10.1038/nbt0695-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place ES, Evans ND, Stevens MM. Complexity in Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Nat. Mater. 2009;8(6):457–470. doi: 10.1038/nmat2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JJ, et al. Engineering the Regenerative Microenvironment with Biomaterials. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2012;2(1):57–71. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, Xia Y. Multiple Facets for Extracellular Matrix Mimicking in Regenerative Medicine. Nanomedicine. 2015;10(5):689–692. doi: 10.2217/nnm.15.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Hamilton GA, Ingber DE. From 3D Cell Culture to Organs-on-Chips. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(12):745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SN, Ingber DE. Microfluidic Organs-on-Chips. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):760–772. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch EW, Bahinski A, Huh D. Organs-on-Chips at the Frontiers of Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14(4):248–260. doi: 10.1038/nrd4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, Khademhosseini A. Seeking the Right Context for Evaluating Nanomedicine: From Tissue Models in Petri Dishes to Microfluidic Organs-on-a-Chip. Nanomedicine. 2015;10:685–688. doi: 10.2217/nnm.15.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Zhao Z, Abdul Rahim NA, Van Noort D, Yu H. Towards a Human-on-Chip: Culturing Multiple Cell Types on a Chip with Compartmentalized Microenvironments. Lab Chip. 2009;9(22):3185–3192. doi: 10.1039/b915147h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes C, Mehta G, Lesher-Perez SC, Takayama S. Organs-on-a-Chip: A Focus on Compartmentalized Microdevices. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012;40(6):1211–1227. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung JH, et al. Microfabricated Mammalian Organ Systems and Their Integration into Models of Whole Animals and Humans. Lab Chip. 2013;13(7):1201–1212. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41017j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikswo JP. The Relevance and Potential Roles of Microphysiological Systems in Biology and Medicine. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014;239(9):1061–1072. doi: 10.1177/1535370214542068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yum K, Hong SG, Healy KE, Lee LP. Physiologically Relevant Organs on Chips. Biotechnol. J. 2014;9(1):16–27. doi: 10.1002/biot.201300187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomi M, Atala A, Coppi PD, Soker S. Principals of Neovascularization for Tissue Engineering. Mol. Aspects Med. 2002;23(6):463–483. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(02)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, Au P, Tam J, Duda DG, Fukumura D. Engineering Vascularized Tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23(7):821–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt0705-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouwkema J, Rivron NC, Van Blitterswijk CA. Vascularization in Tissue Engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26(8):434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, et al. Building Vascular Networks. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4(160):123. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouwkema J, Khademhosseini A. Vascularization and Angiogenesis in Tissue Engineering: Beyond Creating Static Networks. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(9):733–745. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perets A, et al. Enhancing the Vascularization of Three-Dimensional Porous Alginate Scaffolds by Incorporating Controlled Release Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor Microspheres. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2003;65(4):489–497. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies NH, Schmidt C, Bezuidenhout D, Zilla P. Sustaining Neovascularization of a Scaffold through Staged Release of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB. Tissue Eng. A. 2012;18(1-2):26–34. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell JM, Baber MA, Caplan AI. Influence of Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells on in Vitro Vascular Formation. Tissue Eng. A. 2009;15(7):1751–1761. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quint C, et al. Decellularized Tissue-Engineered Blood Vessel as an Arterial Conduit. Proct. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108(22):9214–9219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019506108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S-W, Zhang Y, Macewan MR, Xia Y. Neovascularization in Biodegradable Inverse Opal Scaffolds with Uniform and Precisely Controlled Pore Sizes. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2013;2(1):145–154. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi K, Shimizu T, Okano T. Construction of Three-Dimensional Vascularized Cardiac Tissue with Cell Sheet Engineering. J. Controlled Release. 2015;205:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, et al. 3D Bioprinting for Tissue and Organ Fabrication. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017;45(1):148–163. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malda J, et al. 25th Anniversary Article: Engineering Hydrogels for Biofabrication. Adv. Mater. 2013;25(36):5011–5028. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SV, Atala A. 3d Bioprinting of Tissues and Organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32(8):773–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JS, et al. Rapid Casting of Patterned Vascular Networks for Perfusable Engineered Three-Dimensional Tissues. Nat. Mater. 2012;11(9):768–774. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertassoni LE, et al. Hydrogel Bioprinted Microchannel Networks for Vascularization of Tissue Engineering Constructs. Lab Chip. 2014;14(13):2202–2211. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00030g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolesky DB, et al. 3d Bioprinting of Vascularized, Heterogeneous Cell-Laden Tissue Constructs. Adv. Mater. 2014;26(19):3124–3130. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VK, et al. Creating Perfused Functional Vascular Channels Using 3d Bio-Printing Technology. Biomaterials. 2014;35(28):8092–8102. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, et al. Bioprinted Thrombosis-on-a-Chip. Lab Chip. 2016;16:4097–4105. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00380j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee T, et al. Writing in the Granular Gel Medium. Science Advances. 2015;1(8):1500655. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highley CB, Rodell CB, Burdick JA. Direct 3d Printing of Shear-Thinning Hydrogels into Self-Healing Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2015;27(34):5075–5079. doi: 10.1002/adma.201501234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton TJ, et al. Three-Dimensional Printing of Complex Biological Structures by Freeform Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels. Science Advances. 2015;1(9):1500758. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W, et al. Direct 3d Bioprinting of Perfusable Vascular Constructs Using a Blend Bioink. Biomaterials. 2016;106:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. In Vitro Study of Directly Bioprinted Perfusable Vasculature Conduits. Biomaterials Science. 2015;3(1):134–143. doi: 10.1039/C4BM00234B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, He Y, Fu J-Z, Liu A, Ma L. Coaxial Nozzle-Assisted 3D Bioprinting with Built-in Microchannels for Nutrients Delivery. Biomaterials. 2015;61:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornock R, Beirne S, Thompson B, Wallace GG. Coaxial Additive Manufacture of Biomaterial Composite Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Biofabrication. 2014;6(2):025002. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/2/025002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan B, Hockaday LA, Kang KH, Butcher JT. 3D Bioprinting of Heterogeneous Aortic Valve Conduits with Alginate/Gelatin Hydrogels. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2013;101(5):1255–1264. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skardal A, et al. Photocrosslinkable Hyaluronan-Gelatin Hydrogels for Two-Step Bioprinting. Tissue Eng. A. 2010;16(8):2675–2685. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, et al. Direct Fabrication of a Hybrid Cell/Hydrogel Construct by a Double-Nozzle Assembling Technology. J. Bioact. Compatible Polym. 2009;24(3):249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Visser J, et al. Biofabrication of Multi-Material Anatomically Shaped Tissue Constructs. Biofabrication. 2013;5(3):035007. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/3/035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd DA, Adams AA, Daniele MA, Ligler FS. Microfluidic Fabrication of Polymeric and Biohybrid Fibers with Predesigned Size and Shape. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE. 2014. p. e50958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Daniele MA, Adams AA, Naciri J, North SH, Ligler FS. Interpenetrating Networks Based on Gelatin Methacrylamide and Peg Formed Using Concurrent Thiol Click Chemistries for Hydrogel Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2014;35(6):1845–1856. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele MA, Boyd DA, Adams AA, Ligler FS. Microfluidic Strategies for Design and Assembly of Microfibers and Nanofibers with Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Applications. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2015;4(1):11–28. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele MA, Radom K, Ligler FS, Adams AA. Microfluidic Fabrication of Multiaxial Microvessels Via Hydrodynamic Shaping. RSC Advances. 2014;4(45):23440–23446. [Google Scholar]

- Colosi C, et al. Microfluidic Bioprinting of Heterogeneous 3D Tissue Constructs Using Low Viscosity Bioink. Adv. Mater. 2015;28(4):677–684. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, et al. Bioprinting 3D Microfibrous Scaffolds for Engineering Endothelialized Myocardium and Heart-on-a-Chip. Biomaterials. 2016;110:45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khademhosseini A, et al. Microfluidic Patterning for Fabrication of Contractile Cardiac Organoids. Biomed. Microdevices. 2007;9(2):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s10544-006-9013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue K, et al. Synthesis, Properties, and Biomedical Applications of Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) Hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2015;73:254–271. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loessner D, et al. Functionalization, Preparation and Use of Cell-Laden Gelatin Methacryloyl-Based Hydrogels as Modular Tissue Culture Platforms. Nat. Protocols. 2016;11(4):727–746. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aung A, Theprungsirikul J, Lim HL, Varghese S. Chemotaxis-Driven Assembly of Endothelial Barrier in a Tumor-on-a-Chip Platform. Lab Chip. 2016;16:1886–1898. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00184j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SR, et al. A Bioactive Carbon Nanotube-Based Ink for Printing 2d and 3d Flexible Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2016;28(17):3280–3289. doi: 10.1002/adma.201506420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SR, et al. Aptamer-Based Microfluidic Electrochemical Biosensor for Monitoring Cell Secreted Cardiac Biomarkers. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:10019–10027. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, et al. Google Glass-Directed Monitoring and Control of Microfluidic Biosensors and Actuators. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22237. doi: 10.1038/srep22237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colosi C, et al. Rapid Prototyping of Chitosan-Coated Alginate Scaffolds through the Use of a 3d Fiber Deposition Technique. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2014;2(39):6779–6791. doi: 10.1039/c4tb00732h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, et al. Direct 3D Bioprinting of Prevascularized Tissue Constructs with Complex Microarchitecture. Biomaterials. 2017;124:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zhang Y, Martin JA, Ozbolat IT. Evaluation of Cell Viability and Functionality in Vessel-Like Bioprintable Cell-Laden Tubular Channels. J. Biomech. Eng. 2013;135(9):091011–091011. doi: 10.1115/1.4024575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yu Y, Chen H, Ozbolat IT. Characterization of Printable Cellular Micro-Fluidic Channels for Tissue Engineering. Biofabrication. 2013;5(2):025004. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/2/025004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yu Y, Ozbolat IT. Direct Bioprinting of Vessel-Like Tubular Microfluidic Channels. J. Nanotechnol. Eng. Med. 2013;4(2):020902. [Google Scholar]

- Dolati F, et al. In Vitro Evaluation of Carbon-Nanotube-Reinforced Bioprintable Vascular Conduits. Nanotechnology. 2014;25(14):145101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/14/145101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen CJ, et al. High-Throughput Printing Via Microvascular Multinozzle Arrays. Adv. Mater. 2013;25(1):96–102. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]