Abstract

α-Synuclein (aSyn), β-Synuclein (bSyn), and γ-Synuclein (gSyn) are members of a conserved family of chaperone-like proteins that are highly expressed in vertebrate neuronal tissues. Of the three synucleins, only aSyn has been strongly implicated in neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease, Dementia with Lewy Bodies, and Multiple System Atrophy. In studying normal aSyn function, data indicate that aSyn stimulates the activity of the catalytic subunit of an abundantly expressed dephosphorylating enzyme, PP2Ac in vitro and in vivo. Prior data show that aSyn aggregation in human brain reduces PP2Ac activity in regions with Lewy body pathology, where soluble aSyn has become insoluble. However, because all three synucleins have considerable homology in the amino acid sequences, experiments were designed to test if all can modulate PP2Ac activity. Using recombinant synucleins and recombinant PP2Ac protein, activity was assessed by malachite green colorimetric assay. Data revealed that all three recombinant synucleins stimulated PP2Ac activity in cell-free assays, raising the possibility that the conserved homology between synucleins may endow all three homologs with the ability to bind to and activate the PP2Ac. Co-immunoprecipitation data, however, suggest that PP2Ac modulation likely occurs through endogenous interactions between aSyn and PP2Ac in vivo.

Keywords: Neuroscience, Issue 126, Colorimetric assay, dephosphorylation, malachite, phosphate, phosphatase activity, PP2A catalytic subunit, recombinant proteins, synucleins, threonine phosphopeptide

Introduction

Studies defining the distribution of synucleins in brain and spinal cord show that all three synucleins are enriched in neural tissues, although varying patterns of localization have been reported1. For instance, aSyn is most abundant at presynaptic sites in cerebral cortex and basal ganglia2,3, bSyn has a more uniform distribution in brain and spinal cord4,5, and gSyn is more abundant in spinal cord and peripheral ganglia6. Although some embryonic expression of all synucleins may occur, the three homologs become more abundant during the neonatal period4,5,6,7,8. Remarkably, data from synuclein triple knockout mice, indicate that loss of all three synucleins causes age onset neuronal dysfunction9, supporting important synuclein functions in the central nervous system (CNS)10,11. It is not yet known if synuclein triple knockout mice show changes in PP2Ac distribution or activity. Data from single synuclein knockout mice reveal that loss of aSyn alone is able to significantly reduce PP2Ac activity in brain12. In addition to the CNS, all synucleins localize to other tissues throughout the body13,14,15.

Because of its well-established genetic links to neurodegeneration16,17, aSyn is among the best studied of the three synucleins. The Perez laboratory has long worked to define normal functional activities of aSyn, especially in the CNS11,12,18,19,20,21,22,23 and more recently in peripheral tissues24,25. Among these, was the discovery that aSyn plays a key regulatory role in stimulating PP2Ac activity19. PP2A activity contributes widely to normal brain function, including for the regulation of dopamine production26. The PP2A holoenzyme consists of three independent subunits, the catalytic C subunit, PP2Ac, a scaffolding A subunit, and one of several different regulatory/targeting B subunits that help localize PP2A to specific subcellular microdomains, thus providing PP2A functional diversity27. Evidence shows that aSyn interactions with PP2Ac contribute significantly to its phosphatase activity in vitro and in vivo12,19,21,23,25. When aSyn accumulates in protein aggregates, as it does when Lewy bodies form inside neurons of Parkinson's disease and Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), tissues with aggregated aSyn have diminished PP2Ac activity23,25, when levels of soluble aSyn diminish. Given that all three synucleins have significant homology28 (aSyn shares 66% identity with bSyn and 56% with gSyn) and that aSyn contributes to the activation of PP2Ac, it was hypothesized that all members of the synuclein protein family may be able to increase PP2Ac activity, at least in vitro. To assess this, PP2Ac activity was measured in response to recombinant aSyn, bSyn, and gSyn using a simple colorimetric assay, modeled after the method of Fathi et al.29. This method and the novel findings are detailed herein.

Protocol

1. Preparation of Buffers and Reagents

- Preparation of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) buffer

- Prepare 50 mL of pNPP buffer as follows.

- Weigh out 0.30285 g Tris base (see the Table of Materials) and dissolve it in 25 mL of ultrapure deionized water.

- Add 41.6 µL of 120 mM CaCl2. Adjust to pH 7.0 with 1 M HCl and bring the final solution volume to 50 mL with ultrapure deionized water.

- Ensure that the final concentration is 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM CaCl2, pH 7.0.

- Store pNPP buffer at 4 oC.

- For malachite green solutions, prepare the following.

- Prepare solution A by adding 32.8 mL of concentrated HCl to 67.2 mL of ultrapure deionized water to create a 4 M HCl solution. NOTE: Malachite solution is prepared in a fume hood using disposable gloves, face-mask, and safety goggles.

- Prepare solution B by weighing out 4.2 g of ammonium molybdate and adding it to 95.8 mL of solution A.

- Prepare solution C by weighing out 0.045 g malachite green oxalate salt and adding ultrapure deionized water to bring the final total volume to 100 mL.

- Prepare solution D by mixing solutions B and C at 1:3 (v/v) ratio, stir for 1 h at room temperature .

- Filter Solution D through a 0.22 µm pore size nitrocellulose membrane filter unit using a 50 mL syringe.

- Store prepared malachite solution at 4 oC protected from light.

- Preparation of activator

- To prepare a 1% tween 20 solution, pipette 10 µL of tween 20 into 990 µL of ultrapure deionized water (v/v) then vortex until the tween 20 dissolves completely.

- Preparation of malachite green Tween 20 (MGT) working solution.

- Mix the activator (step 1.3) with the malachite green solution (solution D, step 1.2.5) in a ratio of 1:100 (e.g. 1 µL activator to 99 µL malachite green solution).

- Preparation of threonine phosphopeptide (KRpTIRR) (pT) substrate.

- To prepare a 2 mM stock, place a 1 mg phosphopeptide vial on ice, add 550 µL of ultrapure deionized water, and vortex gently to dissolve.

- Make ~10 aliquots and store pT at -20oC.

- Synuclein Preparation

- Prepare synucleins in a fume hood using disposable gloves, face-mask, and safety goggles.

- Resuspend 1 mg of recombinant synuclein in 1 mL ultrapure deionized water for a final concentration of 1 mg/mL.

- Vortex gently to dissolve and place on ice.

- Prepare 50 µL aliquots and store at -80 oC.

- Preparation of phosphate standards

- Prepare the 0.1 mM phosphate stock solution as follows.

- Weigh out 0.1361 g KH2PO4 and place in a beaker with 80 mL of ultrapure deionized water. Add a stir bar and mix to dissolve. Transfer all of the solution to a graduated cylinder and bring the final total volume to 100 mL with ultrapure deionized water.

- Filter the entire solution through a 0.22 µm pore size nitrocellulose membrane filter unit using a 50 mL syringe; the final concentration is 10 mM.

- Dilute the solution (10 mM) 1:100; the final concentration will be 0.1 mM phosphate (PO4) to be used for assay standards.

- Store the phosphate stock solution at 4 oC.

- See Table 1 for limiting dilutions used to make PO4 standards with a final total volume of 1250 µL each. Add the appropriate amount of phosphate and ultrapure deionized water to 1.5 mL tubes as per Table 1.

- Store prepared PO4 standards at -20 oC.

| Phosphate Standards | ||||||

| 0.1 mM PO4 solution (mL) | 0 | 75 | 150 | 300 | 600 | 1,200 |

| Ultrapure deionized water (mL) | 1,250 | 1,175 | 1,100 | 950 | 650 | 50 |

| Final concentration of PO4 [pmol] | 0 | 150 | 300 | 600 | 1,200 | 2,400 |

Table 1: Phosphate Standards.

2. PP2A Assay in Response to Recombinant Synucleins

NOTE: The total final volume for each reaction will be 60 µL, so the experimenter must adjust the initial volume of pNPP buffer appropriately to accommodate the volume of synucleins used for each sample. In most cases, the volume of pNPP buffer will be between 40 and 44 µL.

- Prepare each PP2Ac reaction as follows.

- In a 1.5 mL tube, add 39 µL of pNPP buffer and place on ice.

- Add 1 µL (105 ng/µL or 0.0007 U/µL) of human recombinant PP2Ac (rPP2Ac).

- Add 4 µL of 0, 1.5, 7.5, 15 or 30 µM synucleins to rPP2Ac in pNPP buffer for final concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 µM and incubate at 4 °C for 30 min on a rotating unit; the final volume will be 60 µL.

- After 30 min, move samples to ice and add 16 µL of 2 mM pT substrate.

- Incubate each PP2A assay mixture for 10 min at 30 °C in a water bath with intermittent shaking.

- To a flat bottom 96-well plate, add 25 µL of each PO4 standard (0, 150, 300, 600, 1,200, and 2,400 pmol) in duplicate wells from low to high.

- Next add 25 µL of each experimental sample (PP2A assay ± synuclein), prepared in steps 2.1.1 to 2.1.6, to duplicate wells on the same 96-well plate.

- Next, add 75 µL of MGT working solution to each well containing standards and samples.

- Leave plate at room temperature for 10 min.

- Observe a color change in samples having measurable differences in phosphate levels.

3. Photometric Analysis

Analyze the 96-well plate containing standards and samples using a spectrophotometric plate reader with the wavelength set to 630 nm29.

Plot the absorbance curve produced (samples read at 630 nm) and note that it remains linear up to 2,400 pmol concentration of PO4.

Representative Results

Protein function and activity can be altered by post translational modifications, such as phosphorylation. Many proteins can be phosphorylated by a kinase, or dephosphorylated by a phosphatase. In the case of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), this multisubunit phosphatase facilitates the dephosphorylation of serine and threonine residues on a broad number of phosphoproteins. Abnormal PP2A activity can lead to dysregulation of protein function which occurs in many diseases, including Parkinson's disease where aSyn can become hyperphosphorylated, and in Alzheimer's disease where tau protein can become hyperphosphorylated. This provided justification for optimizing an in-house procedure to rapidly evaluate PP2Ac activity and determine if abnormal PP2Ac activity may lead to cellular dysfunction.

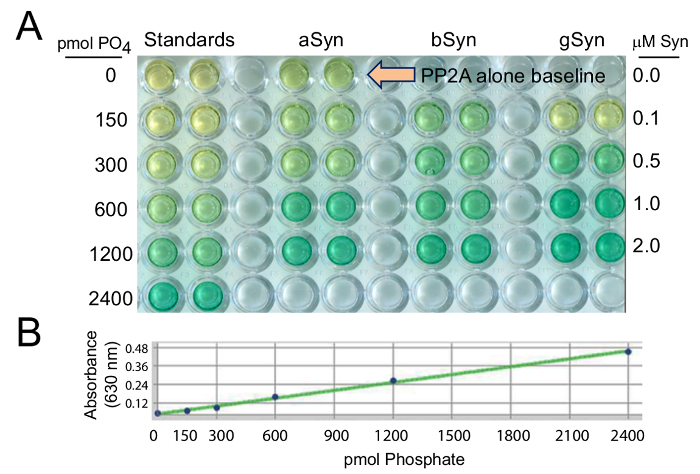

Using this cell-free colorimetric assay, PP2Ac activity was measured by quantifying the amount of free PO4 cleaved from the pT substrate (Figure 1A) and compared to known picomolar amounts of PO4 in the standard curve (Figure 1B). PP2Ac activity was also measured in response to 0.0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 µM synucleins (Figure 1A), as compared to baseline PP2Ac activity in the absence of added synuclein (at the large arrow in Figure 1A).

Figure 1: PP2A activation by recombinant synucleins, is measured relative to known levels of phosphate in the standards. In (A) aSyn, bSyn, and gSyn were evaluated in a range from 0 - 2 µM protein concentrations, to compare to 0 - 2400 pmol PO4 standards. (B) A standard curve for the malachite green PP2Ac assay was generated to provide known amounts of phosphate against which values obtained in experimental conditions can be calculated. In all cases, when PP2Ac activity increases, the amount of free PO4 cleaved from the pT substrate increases and produces a darker green color. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

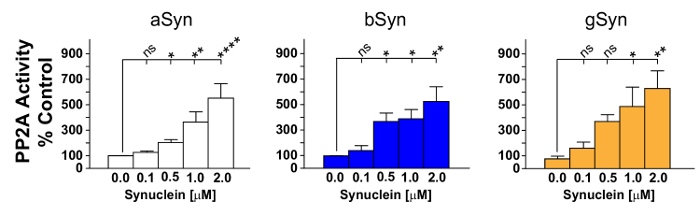

The results show that addition of synucleins to PP2Ac in the initial incubation step could increase the amount of free PO4 measured, thereby demonstrating increased PP2Ac activity. The statistical analysis after many repetitions show that all three recombinant synucleins (aSyn, bSyn, gSyn) significantly increase PP2Ac activity (Figure 2). These results suggest that changes in the amount of soluble cellular synucleins can alter PP2Ac activity; and thus may impact cellular homeostasis. It is not known, however, if all three synucleins contribute to the activation of PP2Ac in vivo, though data in Figure 3 suggest that aSyn likely contributes to PP2Ac activity in vivo.

Figure 2: PP2Ac activity is stimulated by all three synucleins. Graphical representation of PP2Ac activation in response to varying concentrations of recombinant aSyn, bSyn or gSyn is shown. All three recombinant synucleins stimulated PP2Ac activity. aSyn in most experiments appeared to be slightly more potent, though ANOVAs performed using statistical software were remarkably similar overall. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 4-9 independent experiments. ns, not significant; * p <0.05; ** p <0.01; **** p <0.0001. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

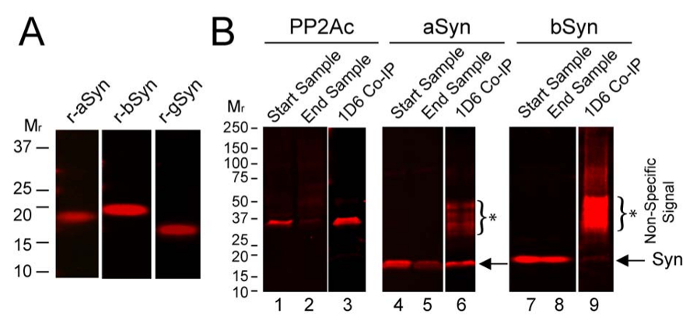

To assess which synuclein(s) can interact with PP2Ac in brain, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays were performed using wild type mouse brain and the PP2Ac-specific-antibody, 1D6. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and blots were probed for PP2Ac, aSyn, bSyn, and gSyn using established methods19. Recombinant synuclein controls demonstrate aSyn, bSyn and gSyn antibody specificity (Figure 3A). Co-IP data reveal that the major synuclein associated with PP2Ac in brain was aSyn, as much less bSyn came down in the co-IP (Figure 3B), and no gSyn came down in the Co-IP (data not shown). This suggests a distinctive role for endogenous aSyn in the regulation of PP2Ac in brain. It also raises the possibility that PP2Ac modulation with bSyn-based-therapies could have potential to restore PP2A activity in those with synucleinopathy, as bSyn is known to be nonamyloidogenic yet as shown here can stimulate PP2Ac30,31.

Figure 3: Interaction of PP2Ac with endogenous synucleins in mouse brain. (A) Recombinant aSyn, bSyn and gSyn were probed with synuclein specific antibodies as described below. (B) Using mouse brain homogenate Co-IP was performed with antibody 1D6, then samples were analyzed on immunoblots. Data are shown for PP2Ac, aSyn, and bSyn, but not for gSyn which did not Co-IP with PP2Ac. Start samples show relative levels of PP2Ac (lane 1), aSyn (lane 4), and bSyn (lane 7) in the initial homogenates. End samples show the remaining levels of PP2Ac (lane 2), aSyn (lane 5), and bSyn (lane 8) in homogenates after the 1D6 PP2Ac Co-IP. Significant levels of PP2Ac were immunoprecipitated using 1D6 antibody (lane 3), which also brought down ample amounts of aSyn (lane 6, at arrow) but very little bSyn (lane 9, strongly overexposed to show faint bSyn signal, at arrow). *Asterisks and brackets mark the non-specific signals on blots. See the Table of Materials for details on antibodies used. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

This malachite green assay with pT was used to measure PP2Ac activity because it is easier to perform than the classical method that uses 32P-labelled substrates. Another advantage of this assay over radioactive assays is that radioisotopes pose some risk and can be costly, especially 32P-labelled molecules that have short half-lives, which limits the number of assays one can perform before reagents expire. Using malachite green rather than radioactivity also eliminates the need to dispose of 32P waste. Malachite green assays are also quite sensitive when measuring the activity of serine/threonine phosphatases when compared to another colorimetric assay that uses the substrate p-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP), which is non-selective as it can be dephosphorylated by a broad number of enzymes32.

Commercial malachite green kits to measure PP2A activity have been available for some time, and were previously used in the laboratory. However, when doing many malachite green assays, such kits became prohibitively expensive. In addition, commercial kits for PP2A activity are stable only for one year, while having reagents available in powdered form and with proper storage, provide readily available assay components that are structurally stable for long periods of time.

Before testing bSyn and gSyn, aSyn was used as a positive control to stimulate PP2Ac activity and to determine the amount of PP2Ac required for the assays, and also to confirm that resulting data remain on the scale with the standard curve (150 - 2400 pmol of PO4). It is noteworthy that if aSyn stimulates PP2Ac too strongly, though the reaction is typically linear, data will go off scale and chemicals in the MGT solution precipitate, making it impossible to measure accurate amounts of released free-PO4 with a plate reader.

Given that aSyn contributes to PP2Ac activity in vivo and in vitro12,19,21,23,25, and that all synucleins have considerable homology, it had been hypothesized that all synuclein family members may be able to stimulate PP2Ac in cell free assays. Using the colorimetric assay described here, it was found that indeed, all three recombinant synucleins (aSyn, bSyn, gSyn) stimulated PP2Ac activity, raising the possibility that all three synucleins may perform similar functions in the nervous system. However, brain from Parkinson's or Dementia with Lewy Body cases have less PP2Ac activity in tissues containing highly aggregated aSyn23. Mouse tissues harboring Lewy body-like pathology also exhibit reduced PP2Ac activity25. This, and new data in Figure 3 as well as prior data from aSyn knockout mice12, strongly suggest that neither bSyn nor gSyn can typically compensate for the loss of soluble aSyn in brain, or alternatively that those synuclein homologs may not associate with PP2Ac as strongly as aSyn as shown (Figure 3). The Allen Brain Atlas shows colocalization of all three synuclein mRNAs in many brain areas, and though triple synuclein knockout mice have been generated9,33, PP2Ac activity has not been assessed in that model. Interestingly, aSyn that is phosphorylated on Ser129 by Polo-like kinase 2, is less able to activate PP2Ac12, but evidence shown here for bSyn suggest that bSyn phosphorylation is unlikely to impact PP2Ac activity, as very little bSyn came down with PP2Ac in mouse brain (Figure 3). Taken together, the data suggest that endogenous PP2Ac activity modulators, like aSyn, likely contribute to wellness and disease.

The protocol outlined here is a simple yet powerful technique to determine the capacity of PP2Ac to dephosphorylate a phosphopeptide substrate in response to various treatments. For instance, this same methodology can be used to test other PP2Ac activators, such as ceramides as well as potential novel therapeutics34, or to assess the impact of PP2Ac inhibitors in vitro. It is also important to point out that similar assays can measure the activity of PP2Ac that has been isolated by 1D6 immunoprecipitation from cell extracts or body tissues, as previously described by the authors12,19,25. Future applications for the malachite green assay exist beyond measuring PP2Ac activity, as ATP activity can also be determined using such an assay.

Note, a standard curve must be generated each time for every independent PP2Ac assay. It is mandatory to ensure that all reagents used are phosphate free, as free phosphates artificially increase background signal and produce erroneous results. On the day of the assay it is essential to prepare enough fresh MGT solution for all samples to be assayed. Also, MGT is only good the day that it is made and tends to precipitate after a few hours. PP2Ac purchased from a vendor must be aliquotted and stored frozen soon after it is received to prevent freeze thaw cycles that reduce its activity. As other phosphatases can dephosphorylate the pT substrate (e.g. PP1 and PP535), when analyzing cell or tissue extracts in which PP2Ac has not been isolated by immunoprecipitation, samples must be passed over columns to remove free phosphates and specific inhibitors of phosphatases must be used to confirm phosphatase specificity, as previously described18.

Disclosures

Dr. Perez was a member of the faculty in the Department of Neurology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine from 1999 – 2011.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate efforts by prior laboratory members Kendra Mackett, Sandra Slusher, and Jie Chen who worked to optimize the method. The authors also thank the National Institutes of Health, Michael J. Fox Foundation, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso Scholarly Activity Research Project (SARP), Lizanell and Colbert Coldwell Foundation, Multiple System Atrophy Coalition, Hoy Family Research, and Anna Mae Doyle Gift Funds for financial support of this research.

References

- Li J, Henning Jensen P, Dahlstrom A. Differential localization of alpha-, beta- and gamma-synucleins in the rat CNS. Neurosci. 2002;113(2):463–478. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai A, et al. The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer's disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron. 1995;14(2):467–475. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, et al. Characterization of the precursor protein of the non-A beta component of senile plaques (NACP) in the human central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55(8):889–895. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama-Imazu T, et al. Cell and tissue distribution and developmental change of neuron specific 14 kDa protein (phosphoneuroprotein 14) Brain Res. 1993;622(1-2):17–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90796-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajo S, Shioda S, Nakai Y, Nakaya K. Localization of phosphoneuroprotein 14 (PNP 14) and its mRNA expression in rat brain determined by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;27(1):81–86. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman VL, et al. Persyn, a member of the synuclein family, has a distinct pattern of expression in the developing nervous system. J Neurosci. 1998;18(22):9335–9341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09335.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JM, Jin H, Woods WS, Clayton DF. Characterization of a novel protein regulated during the critical period for song learning in the zebra finch. Neuron. 1995;15(2):361–372. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers GS, George JM, Banker GA, Clayton DF. Delayed localization of synelfin (synuclein, NACP) to presynaptic terminals in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;99(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(96)00210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten-Harrison B, et al. alphabetagamma-Synuclein triple knockout mice reveal age-dependent neuronal dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(45):19573–19578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005005107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benskey MJ, Perez RG, Manfredsson FP. The contribution of alpha synuclein to neuronal survival and function - Implications for Parkinson's Disease. J Neurochem. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Perez RG, Hastings TG. Could a loss of alpha-synuclein function put dopaminergic neurons at risk? J Neurochem. 2004;89(6):1318–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, et al. Serine 129 phosphorylation reduces the ability of alpha-synuclein to regulate tyrosine hydroxylase and protein phosphatase 2A in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(23):17648–17661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akil O, et al. Localization of Synucleins in the Mammalian Cochlea. JARO. 2008;9(4):452–463. doi: 10.1007/s10162-008-0134-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardia-Laguarta C, et al. alpha-Synuclein Is Localized to Mitochondria-Associated ER Membranes. J Neurosci. 2014;34(1):249–259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2507-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibayama-Imazu T, et al. Distribution of PNP 14 (beta-synuclein) in neuroendocrine tissues: localization in Sertoli cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 1998;50(2):163–169. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199806)50:2<163::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(7):492–501. doi: 10.1038/35081564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Del Tredici K, Braak H. 100 years of Lewy pathology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(1):13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alerte TN, et al. Alpha-synuclein aggregation alters tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation and immunoreactivity: lessons from viral transduction of knockout mice. Neurosci Lett. 2008;435(1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Tehranian R, Dietrich P, Stefanis L, Perez RG. Alpha-synuclein activation of protein phosphatase 2A reduces tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation in dopaminergic cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 15):3523–3530. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez RG, et al. A role for alpha-synuclein in the regulation of dopamine biosynthesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22(8):3090–3099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03090.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porras JL, Perez RG. Ch. III. In: Kanowitz HC, Polizzi M, editors. Nova Publishers - Alpha-Synuclein. NOVA Science Publishers; 2014. pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tehranian R, Montoya SE, Van Laar AD, Hastings TG, Perez RG. Alpha-synuclein inhibits aromatic amino acid decarboxylase activity in dopaminergic cells. J Neurochem. 2006;99(4):1188–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, et al. Lewy-like aggregation of alpha-synuclein reduces protein phosphatase 2A activity in vitro and in vivo. Neuroscience. 2012;207:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X, et al. alpha-Synuclein binds the K(ATP) channel at insulin-secretory granules and inhibits insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300(2):E276–E286. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00262.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell KF, et al. Non-motor parkinsonian pathology in aging A53T alpha-synuclein mice is associated with progressive synucleinopathy and altered enzymatic function. J Neurochem. 2014;128(4):536–546. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens V, Goris J. Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochem J. 2001;353(Pt 3):417–439. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarchak N, Xing Y. PP2A as a master regulator of the cell cycle. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2016;51(3):162–184. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2016.1143913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JM. The synucleins. Genome Biol. 2002;3(1) doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-3-1-reviews3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fathi AR, Krautheim A, Lucke S, Becker K, Juergen Steinfelder H. Nonradioactive technique to measure protein phosphatase 2A-like activity and its inhibition by drugs in cell extracts. Anal Biochem. 2002;310(2):208–214. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, et al. An antiaggregation gene therapy strategy for Lewy body disease utilizing beta-synuclein lentivirus in a transgenic model. Gene Ther. 2004;11(23):1713–1723. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Mallory M, Masliah E. beta-Synuclein inhibits alpha-synuclein aggregation: a possible role as an anti-parkinsonian factor. Neuron. 2001;32(2):213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy T, Nairn AC. Serine/threonine protein phosphatase assays. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010;Chapter 18 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1818s92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar S, et al. Functional alterations to the nigrostriatal system in mice lacking all three members of the synuclein family. J Neurosci. 2011;31(20):7264–7274. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6194-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Medrano J, et al. Novel FTY720-based compounds stimulate neurotrophin expression and phosphatase activity in dopaminergic cells. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5(7):782–786. doi: 10.1021/ml500128g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swingle M, Ni L, Honkanen RE. Moorhead G. Methods in Molecular Biology. 365, Protein Phosphatase Protocols. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2007. Chapter 3, Small-molecule inhibitors of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases; pp. 23–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]