Abstract

Objective

To describe parents’ perspectives and likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in the NICU and identify barriers and facilitators to parents speaking up.

Design

Exploratory, qualitatively-driven, mixed-methods design using questionnaires, interviews, and observations with parents of newborns in the NICU. The qualitative investigation was based on constructivist grounded theory. Quantitative measures included ratings and free text responses about likelihood of speaking up in response to a hypothetical scenario about lack of clinician hand hygiene. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were integrated in the final interpretation.

Setting

A 50-bed, US, academic medical center, open-bay NICU.

Participants

Forty-six parents completed questionnaires, 14 of whom were also interviewed.

Results

Most parents (75%) rated themselves likely or very likely to speak up in response to lack of hand hygiene; 25% of parents rated themselves unlikely to speak up in the same situation. Parents engaged in a complex process of Navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU that entailed learning the NICU, being deliberate about decisions to speak up, and at times choosing silence as a safety strategy. Decisions about how and when to speak up were influenced by multiple factors including knowing the newborn, knowing the team, having a defined pathway for voicing concerns, clinician approachability, clinician availability and friendliness, and clinician responsiveness.

Conclusions

To engage parents as full partners in safety, clinicians need to recognize the complex social and personal dimensions of the NICU experience that influence parents’ willingness to speak up about their safety concerns.

Keywords: Communication, Neonatal Intensive Care, Parents, Patient safety

Neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) represent a challenging environment in which to maintain patient safety. Neonates born too early or with medical problems are uniquely vulnerable to iatrogenic harm because of their small size, physiologic immaturity, and likelihood of receiving complex medical therapy in a highly technical environment over an extended length of stay (Raju, Suresh, & Higgins, 2011). Smaller neonates and those born at earlier gestational ages are even more vulnerable: their natural defenses may be extremely underdeveloped, they are likely to require multiple medications, and their medication dosing changes frequently as they grow and develop (Kugelman et al., 2008). The consequences of even small errors can be serious given the neonate’s limited physiologic resilience (Raju et al., 2011). Moreover, in retrospective and prospective studies, researchers estimated that 56–83% of adverse or iatrogenic events identified in NICU patients were preventable (Kugelman et al., 2008; Sharek et al., 2006).

In 2011 the Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute for Child Health and Development issued a call for NICU-specific safety research and stated a need for systematic research with a focus on causal factors of NICU harm, human factors, systems, and culture in the NICU (Raju et al., 2011). This document highlighted the importance of reporting errors and near misses, the importance of good safety-focused cultures that encourage such reporting, the importance of systems thinking, and the need to understand how families can contribute to error prevention and mitigation. One way to extend our thinking about safety is to think about relationships between parents and clinicians as part of the system within which care is delivered and to evaluate communication between parents and clinicians as a reflection of safety culture.

Callout 1

Effective communication among team members and with patients is a hallmark of safe and highly reliable patient care (Institute of Medicine, 1999; Page, 2004). Identifying safety concerns and communicating effectively with team members about these concerns can lower injury risk by preventing potential harmful conditions and errors (Leonard, Graham, & Bonacum, 2004; Page, 2004; Simpson & Knox, 2003). However, communication and teamwork breakdowns are among the leading contributors to serious adverse events (The Joint Commission, 2015). Most research and improvement work on communication and teamwork has focused on clinicians, but calls for patient and family involvement in safety are growing in adult and pediatric health care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) conducted an environmental scan of patient and family engagement in safety and quality. They found that existing hospital- and individual-level engagement strategies and tools were not integrated (i.e., system-level strategies do not include individual-level tools for parents and vice-versa); were not informed by patient/family experiences; did not include concrete, actionable behavioral support for individuals; and neglected the importance of nurse-patient communication in maintaining safety (Maurer, Dardess, Carman, Frazier, & Smeeding, 2012).

Efforts to engage patients and families in helping to maintain safety for themselves or their loved ones have included encouraging patients and families to speak up about their concerns, and for example, ask clinicians to wash their hands (Entwistle, Mello, & Brennan, 2005; Martin, Navne, & Lipczak, 2013; Mohsin-Shaikh, Garfield, & Franklin, 2014; Schwappach, 2010; The Joint Commission, 2011). However, patients and family members may experience substantial barriers to speaking up (Davis, Sevdalis, Jacklin, & Vincent, 2012; Davis, Sevdalis, Pinto, Darzi, & Vincent, 2013; Davis, Savvopoulou, Shergill, Shergill, & Schwappach, 2014; Entwistle et al., 2010; Hurst, 2001; Rosenberg, Rosenfield, Silber, Deng, & Sullivan-Bolyai, 2016; Schwappach, 2010). While patients and family members can indeed identify safety problems, their concerns sometimes differ from clinicians’ concerns and they may not articulate their concerns due to fear of potential consequences of doing so (Entwistle et al., 2010; Hurst, 2001; Khan et al., 2016; Rosenberg et al., 2016; Schwappach, 2010).

Evidence for appropriate mechanisms of patient engagement is limited, and exploration of patients’ or family members’ perspectives on speaking up about safety concerns in inpatient settings has been sparse (Berger, Flickinger, Pfoh, Martinez, & Dy, 2014; Lyndon, Jacobson, Fagan, Wisner, & Franck, 2014; Rosenberg, et al., 2016). Several scholars have raised concern that existing programs to engage patients and families in safety may represent an un-tested and potentially harmful shifting of responsibility from providers to patients (Entwistle et al., 2010; Schwappach, 2010; Scott, Heavey, Waring, Jones, & Dawson, 2016). The available research findings suggested that speaking up is often difficult and insufficient in identifying or resolving safety concerns. For example, in their study of maternity patients in the United Kingdom, Rance et al. (2013) found that when mothers raised concerns classified as “safety alerts,” these concerns were not consistently addressed, while Rosenberg et al. (2016) found that parents on a pediatric ward balanced their safety concerns against the interpersonal risks of speaking up. There are few studies of the role of NICU parents in safety (Lyndon et al., 2014; Raju, Suresh, & Higgins, 2011). The purpose of our exploratory study was to describe parents’ perspectives on speaking up about safety concerns regarding care of their newborns, measure parents’ likelihood of speaking up in response to safety concerns, and to identify barriers and facilitators to parents speaking up about their concerns in the NICU setting.

Methods

We conducted a parallel, convergent, mixed methods study to explore parents’ perspectives on safety, likelihood of speaking up about concerns, and barriers and facilitators to speaking up about safety concerns. The resulting model of parents’ conceptualizations of safety in the NICU includes a combination of actions taken by parents and clinicians to contribute to the newborn’s well-being and safety in three domains: physical, developmental, and emotional. This model of safety along with a detailed discussion of the study methods have been reported elsewhere (Lyndon et al., 2014). This report focuses on the research questions related to parents speaking up about their safety concerns. In brief, we used in-depth interviews, questionnaires, and ethnographic observation to explore the perspectives of parents over 18 years of age who had one or more newborns hospitalized in a 50-bed regional academic tertiary referral center with approximately 250 staff, including nurses, attending physicians, medical residents, and neonatal nurse practitioners and admitted over 500 newborns annually at the time of the study. Parents were approached by nurses from the clinical research service at least 72 hours after admission. There were no diagnosis or gestational-age based inclusion or exclusion criteria. All participants completed questionnaires and a subset of parents participated in interviews and observations based on purposive sampling to include a range of diagnoses and lengths of stay. Participants received $25.00 gift cards for each study activity they completed (questionnaire completion, interview, or observation). The local institutional review board approved the study. All participants gave signed informed consent.

Instruments

The 84-item questionnaire took approximately 25 minutes to complete. The questionnaire included Likert-type multiple choice and open-ended questions about parent demographics, newborn clinical characteristics, parent stress, parent perception of the family-centeredness of the NICU, parent safety concerns, and parent views about the meaning of the term safety in relation to their newborn’s care (Lyndon et al., 2014). Parents were also asked to rate their likelihood of speaking up in response to a hypothetical scenario wherein clinicians demonstrated a lack of hand hygiene in the NICU. Hand hygiene represents a basic safety action that all parents of newborns in the NICU would be exposed to, asked to perform themselves on a frequent basis and be informed about its importance, regardless of the specific clinical circumstances of their newborns. We adapted the hand-hygiene scenario from the Likelihood of Speaking Up Index (Lyndon et al., 2012) to fit the setting of this study (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Hand Hygiene Scenario

| You are in the NICU with your baby and a staff member comes to examine your baby. You have not seen the doctor or nurse wash his or her hands, and the doctor or nurse does not appear to be planning to do so. |

Questions (Response Format – 5 point Likert-type scale)

|

Free text questions:

|

From Predictors of likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in labour and delivery. A. Lyndon, J. B. Sexton, K.R. Simpson, A. Rosenstein, K.A. Lee, and R.M. Wachter, BMJ Quality and Safety, 21(9), 791– 799, 2012. Adapted with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Parent interviews lasting 60 to 90 minutes followed our published semi-structured interview guide (Lyndon et al., 2014). Interviews allowed parents to surface concerns of interest to them and explore them in greater depth than the questionnaire offered. Selected questions are displayed in Table 2. We explored parents’ concerns as they arose without defining safety or speaking up because we aimed to understand the situation from the parents’ perspective. Providing predetermined definitions could have limited our capacity to elicit the parents’ perspective. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Observations allowed real-time observation of communication with clinicians and assessment of the environmental context of care. Observations lasted approximately two hours and were conducted by sitting with parents at the bedside with their newborns. We took notes openly during observations, focusing on parents’ communications with clinicians and on the NICU environment. Interviews and observations were conducted by two nurse scientists with qualitative research training and backgrounds in labor and delivery (AL) and midwifery (CH).

Table 2.

Selected Interview Questions

|

From Parents’ perspectives on safety in neonatal intensive care: a mixed-methods study. A. Lyndon, C. H. Jacobson, K. M. Fagan, K. Wisner, and L.S. Franck, BMJ Quality and Safety, 23(11), 902–9, 2014. Adapted with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Data Analysis

Data related to speaking up from the two study data sources, questionnaires and interview/observation text, were first analyzed separately. For the questionnaires we used descriptive statistics to evaluate demographic and rating-scale question responses and thematic analysis (Braun & Clark, 2006) to evaluate free-text responses. We chose constructivist grounded theory methodology for the interview/observation strand of the study based on our understanding of patient safety and speaking up about safety concerns as dynamic social processes (Lyndon, 2008; Lyndon & Kennedy, 2010; Lyndon et al., 2012).

Grounded theory is primarily focused on understanding interaction and social process. We used dimensional analysis, a specific analytic approach to grounded theory (Schatzmann, 1991) to develop a theoretical explanation of parent’s experience of speaking up in the NICU. As is customary with all forms of grounded theory, we began the analysis with data collection and proceeded iteratively. We read and re-read the transcripts for the overall experiences being presented, and then coded the transcripts for units of meaning using constant comparison to develop open, focused, and theoretical codes to describe dimensions of parents’ experiences related to speaking up (Charmaz, 2006). We used constant comparison of data elements and codes within and across transcripts and theoretical sampling to identify dimensions of experience, develop and differentiate the properties of these dimensions, and account for the range of variation in experience following the procedures of Charmaz (2006), Schatzman (1991), and Kools, McCarthy, Durham, and Robrecht (1996).

We specifically interrogated the data for instances representing what we characterized as silence and voice, and ultimately also silenced voice, and used a dimensional matrix to analyze parents’ experience in terms of the context, conditions, processes, and consequences of action (Kools et al., 1996; Schatzman, 1991). We then compared the resulting grounded theory analysis to the scenario and free-text responses from the questionnaire to determine how the two analyses informed each other, to confirm our theoretical explanation of parents’ experience of speaking up as navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU.

We maintained rigor with reflexive memoing, group discussion, systematic analysis, and member reflection (Tracy, 2010). Three investigators (AL, CH, and KF) coded interview/observation data; a fourth investigator (KW) first independently coded the questionnaire free text responses and later worked with interview/observation data. The fifth investigator (LF) analyzed quantitative questionnaire data. All investigators met regularly to discuss the analysis and resolve any discrepancies. We tracked the origin of data elements throughout analysis and selected illustrative quotes from a range of participants. We asked questions and reflected comments and interpretations back to participants to confirm or correct our understanding of participants’ experiences in an ongoing fashion during interviews and observations. Our research team included 5 nurses with clinical backgrounds in labor and delivery (AL, KW), midwifery (CH), and NICU and pediatrics (KF, LF). Aspects of our roles as nurses recruiting parents in the hospital required continual awareness and management. We noted that parents tended to assume that the investigators conducting interviews and observations were connected to the clinical enterprise. Parents were keen to convey their gratitude for care and positive aspects of their experience. We had to assure maintenance of confidentiality and demonstrate interest in parents’ views before they would discuss situations that could be viewed as negative. We monitored our clinically-based reactions to information presented by parents in interviews and throughout analysis.

Results

Fifty-five parents enrolled, 46 of whom completed questionnaires (86% response rate). The median age of parents was 35 years (range 19–42). Most were first-time parents (61%), married (65%) or partnered (33%), and female (78%). Additional characteristics of the participating parents and their newborns are summarized in Table 1. Fourteen of the 46 responding parents participated in interviews and three of these parents also participated in observations. Interviewed parents had 12 newborns between them. Five of these newborns were included in observations. Eight parents requested we interview them as couples; six were interviewed individually. Overall we found that parents were deliberate in deciding whether or not to speak up about safety concerns, and we characterized the central process they engaged in regarding their concerns as Navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU.

CALLOUT 2

Hand Hygiene Scenario

Forty-four parents (96%) rated the potential for harm from lack of hand hygiene as medium to very high, whereas 2 rated the potential for harm as low or very low. Fewer parents rated themselves likely or very likely to speak up in response to the hand hygiene scenario [34/46 to neonatologist (74%); 36/46 to RN (78%); 33/44 to medical resident (75%)]. Twenty percent of parents (9/46) acknowledged potential for harm, but rated themselves and unlikely or very unlikely to ask clinicians to wash their hands. In response to the question, If you were going to say something to the person about to examine your baby, what might you say? most parents provided what we characterized as direct responses such as “Please wash your hands.” A few parents provided strong indirect prompts, such as “Here, let me get you some hand sanitizer,” and “Do you prefer to use hand gel or wash your hands at the sink?” One parent offered, “Most likely I would not say anything I’d just be worried about the kids.”

Navigating the Work of Speaking Up in the NICU

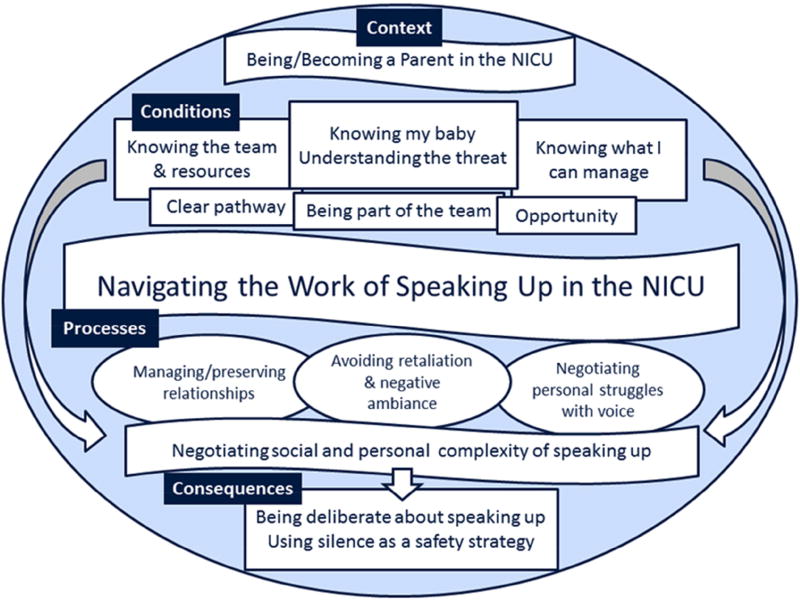

Interviews, observations, and some free text questionnaire responses revealed that speaking up about safety concerns was not straightforward for parents and could be perceived as risky. Parents engaged in Navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU in relation to multiple complex aspects of parent experience (Figure 1). The specifics of each situation influenced parents in coming to their decisions. Thus, parents did not necessarily have a static posture toward speaking up or not speaking up and they sometimes actively chose to remain silent.

Figure 1.

Navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU.

Context: the situation in which experience is embedded

The NICU environment and the clinical status of their premature or ill newborns were unfamiliar for most parents. Thus the context in which parents found themselves was one of being on a trajectory of being/becoming parents in the NICU wherein they had to simultaneously learn about the newborns’ medical conditions and medical and developmental needs and responses, learn about the NICU routines and technology, and learn how to parent their newborns under those circumstances.

I think it’s almost like going from being a freshman in high school to being a senior in two and half months. You know, where the first couple of days you feel awkward, you’re not sure of the layout of the [unit] where everything is, unfamiliar faces, strange noises. Now it’s routine. I mean, we’re completely used to the sounds of the alarm.

Being/becoming a parent in the NICU was challenging because parents were fearful for their newborn’s health, and the clinical situation was often marked by uncertainty and/or setbacks in the newborn’s condition. The need to rely on clinicians for newborn care often removed parents from their roles as primary responders and meant parents were not in control of or able to make decisions about many aspects of care. This all occurred in stark contrast to what parents envisioned for their families before they discovered their newborn’s health was threatened.

And all of a sudden you are in a position that you don’t control the environment and even to go and hold your baby you have to ask for permission, which is really difficult because you never expected it to be like that.

Parents experienced the open-bay NICU as noisy, crowded, and lacking in privacy. They often struggled to obtain the equipment they needed for basic comfort while staying at the bedside to provide parental care, such as breast pumps, breastfeeding chairs, and privacy screens. The lack of privacy and the cramped space exacerbated the parents’ feelings of uncertainty and tension as they underlined the nature of the NICU as a clinician-owned environment.

You know, there are the 6 babies, 12 parents, 2 nurses, and then somehow there’s an extra nurse or two around for whatever reason, and it was so loud, and like a sea of screens…It was loud and that’s not good for preemie development, … and you want to have control over their environment, right? Like you want to be able to close the shades and make things quiet, and you can’t do that in the NICU and that can be hard.

Conditions blocking, facilitating, or shaping safety actions: Knowing and opportunity

Parents accessed three forms of knowing in making their deliberations about how to handle perceived safety concerns: knowing my baby - understanding the threat; knowing what I can manage; and knowing the team and resources. Each of these forms of knowing was situated within the trajectory along being/becoming a parent in the NICU. As parents came to know their newborns and the environment, they learned what helped or challenged their newborns and to recognize which signals from the newborn and the monitors they needed to be concerned about. This knowledge was specific to the individual newborn, as illustrated by parents of twins:

[T]hey’re identical twins…They were expected to be on the same pace and that wasn’t the case. They were so obviously different to me from birth and it was like, “Why are they trying to push her so hard?”… To me it seemed obvious; I didn’t understand why they didn’t see that she was so different. It took many setbacks until [clinicians acknowledged that and changed management].

Parents’ individualized knowledge of their newborn gave them a perspective from which to understand whether or not situations presented safety threats, and if so, how severe the threat was and how they might respond to it.

[I didn’t ask for another nurse] because I was there. If it was [Baby S], I definitely would have said something because there were times where she’s had to be hand-ventilated or reintubated. I mean like she sometimes just falls apart. Where [Baby G], she just needed a little tap and she’d come out of it.…. So that’s where I just sucked it up for the day, and I didn’t mind. I wasn’t scared to do it because I had seen [G’s heart rate drop] so many times … I was at a point where I was, “Oh, she’s doing it again,” and I’d just give her a couple of taps and she’d come out.”

Parents often found it challenging to know whom to speak with about concerns. They identified having a defined pathway for voicing concerns (such as a specified person to talk to or a concerns box), clinician availability and friendliness, and clinician responsiveness as facilitators to speaking up. Parents were keenly aware that clinicians were managing multiple patients. They assessed available resources, competing demands on clinician time and receptiveness, and weighed their standing with the care team in considering their actions. Parents did not want to be perceived as confrontational and were wary of the potential for negative consequences of speaking up about concerns. While parents respected and valued the care provided by nurses, physicians, and others, they expressed concern that if they complained, a clinician could “take it out on my baby” or inadvertently cause harm if the conversation left the clinician distressed or distracted.

Or to take it against the child or the parents, you know? For example, this nurse that I’ve requested for her not to take care of my kids, I’ve seen her in the hallway and clearly she’s not happy about it. So you feel like, okay, we’re not in friendly terms anymore…basically you’ve created a negative ambiance there. So you can’t do that. If you feel that that’s what’s going happen if you give your input, then you won’t because then, the next thing you know when you walk in here, nobody is going to want to talk to you.

Thus, parents balanced their knowledge of their newborns and themselves against their assessment of the potential safety threat and their own capacity to intervene in making decisions about speaking up. However, a condition that blocked action for some parents was opportunity. While most parents felt they were usually well-informed about the care of their newborns, some parents noted that there were multiple situations in which parents were not given opportunity to express concerns. Parents reported that sometimes they did not get timely information about changes in their newborns’ conditions, and at other times procedures were done without their knowledge.

When the decisions were being made about whether he was going to have surgery I just felt like it was being made without involvement from us or without keeping us informed.

One parent stated that she would have been opposed to the decision made by the clinical team and would have expressed her concern to them if she had known what was happening, but she was not informed of the treatment change.

Negotiating the social and personal complexity of speaking up

The context and conditions of parents’ perceptions of safety in the NICU shaped a situation where parents were reflective and deliberate in their decisions about speaking up. Sometimes the risk to their newborns was clear to them, the need to speak up was perceived as straightforward, and parents were very direct. For example, after complications from a tubing disconnection with a critical medication, one parent said:

You know, I was like, “This can’t happen again.” Because we know what happened and we know that that’s preventable. It can’t happen again.… And so, you know, I told the nurse practitioner, I just asked her, “How are we going to communicate this so it doesn’t happen again?”

However, in many situations, parents considered the medical and social complexity of the situation before making a decision about whether or not to speak up about a safety concern. In some cases parents had to negotiate with themselves to overcome their own hesitance to speak up. In some cases they could not overcome their hesitance and felt this reflected negatively on them.

I didn’t have the courage and you feel bad sometimes because you feel you know as a parent you need to speak up because that is your job, to protect them. Yet, you struggle because you don’t naturally have the courage.

In some situations parents actively chose silence as a safety strategy. They used silence to avoid overburdening a visibly stressed clinician, to avoid confrontation, or as a form of impression management. During an observation session a parent related her reflections on her decision to “stop myself” from raising a small concern:

She says it’s because she wants to be perceived as not too worried – she wants to practice being confident and assured. She has been treated as a collaborator and a teammate, and she doesn’t want to disappoint the team by wasting time with the “little stuff.” She talks about making a mindful practice of not getting too worried, staying calm. She notes, “I think its ego. Trying to live up to the image of the mother I want to be: the mother who has the right perspective, ‘everything is ok.’” [observation fieldnote]

The deliberate consideration parents gave to when and how to speak up informs our choice of Navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU as the dimension of parents’ experience that best explains the social process they engage around expressing safety concerns.

CALLOUT 3

Discussion

We used a hand hygiene scenario in our study to elicit parent perceptions of and likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns regarding their newborn’s care in the NICU. We also used interviews and observations to delve more deeply into parent perspectives on speaking up about a range of safety concerns, as defined by the parents, and to appreciate the context within which their concerns arose. Parents in our study almost universally rated lack of hand hygiene as potentially harmful, and most parents rated themselves likely or very likely to speak up if a clinician failed to use proper hand hygiene prior to contact with their newborns. However, about 25% of parents rated themselves as not likely to speak up in this scenario and our analysis revealed that speaking up about safety in the NICU was socially and personally complex.

Parents in our study engaged in a process of Navigating the work of speaking up in the NICU. This entailed learning the NICU, being deliberate about decisions to speak up because speaking up to clinicians was perceived as risky, and at times choosing silence as a safety strategy. These decisions were influenced by multiple factors including the severity of perceived threats to their newborns’ safety, the level of vulnerability of the newborns, clinician receptiveness, parents’ own perceived competence to deal with the concern, and parents’ assessment of other supports in the environment to manage the perceived safety threat.

Our findings extend a growing body of literature on patient and family member engagement in patient safety and confirm the profound difficulty family members face in navigating the medical environment. Fagerahaugh, Strauss, Suzcek, and Wiener (1987) first described the concept of trajectory as encompassing “all of the work” of being a hospitalized patient. We reference this in our choice of the label navigating the work and situating this process within the trajectory of NICU parenting as encompassing all of the work of being the parents of vulnerable newborns. In other studies of parents in neonatal (Hurst, 2001), pediatric (Rosenberg et al., 2016), and adult medical settings (Entwistle et al., 2010) researchers also characterized speaking up as a deliberate process influenced by concern about its potential to damage the patient-clinician relationship or negatively affect care. Asking clinicians to wash their hands has been reported as demanding and difficult for patients (Schwappach & Wernli, 2011). The severity of the threat has also previously been identified as an important factor in decision-making as parents and patients consider whether or not to take the risks involved in raising a concern (Entwistle et al., 2010; Hurst, 2001; Rosenberg et al., 2016).

Despite the consistency of findings about the difficulty of speaking up for patients and family members across several different kinds of settings, clinicians have not necessarily integrated these factors into their safety programs or interventions. Interestingly, clinicians similarly engage in a process of assessing the severity of the threat and weigh this against potential social consequences (e.g. damaging relationships with people they work with every day) or other threats associated with speaking up (e.g. angering a senior clinician), resulting in variability in whether or not clinicians will speak up when they identify potential safety problems (Lyndon, 2008; Lyndon et al., 2012; Raemer, Kolbe, Minehart, Rudolph, & Pian-Smith, 2016; Schwappach & Gehring, 2014; Szymczak, 2015). The fact that communication is so deeply affected by social interaction is not new, but remains under-appreciated in many health care settings.

As our study and other studies show, in many situations the parent experience cannot be cleaved cleanly from myriad environmental and interpersonal factors that ultimately affect patient safety (Doyle, Lennox & Bell, 2013). We suggest that stronger appreciation is needed by clinicians and hospital systems of how integral patient experience is to patient safety. The National Health System in the United Kingdom pioneered methods for co-designing patient engagement pathways with patients and families by involving them at all stages of design, testing, and implementation of quality initiatives (Donetto, Tsianakas, & Robert, 2014; Scott et al., 2016). Patients and families could similarly be proactively invited to co-produce patient safety using co-design techniques and toolkits to improve at the unit and organizational level (The Kings’s Fund, 2013).

Clinical Implications

At the individual level, clinicians should be mindful of the social complexity of being a parent in the NICU and can a) inquire about how parents want to be involved; b) invite parents to co-produce safety with them by teaching parents the teamwork principle of cross-monitoring and consistently asking parents to share observations and concerns (e.g., We all watch out for each other here to make sure things are done safely and correctly. Would you help me do that by letting me know when you have any concerns or think something isn’t right?); and c) involve parents in designing feedback mechanisms for their units. Nurses are in a unique position to provide this proactive inquiry, invitation, and messaging for families, as they have the most consistent contact with families throughout the hospital stay.

Having a clearly defined pathway for voicing concerns, and clinician availability, friendliness, and responsiveness were seen as facilitators of speaking up by parents in our study. These findings are consistent with other reports of actions that facilitate patients and family members speaking up to ask challenging questions or report safety concerns in other settings, including clinician encouragement, being invited to engage, and positive communication with clinicians (Davis, Sevdalis, & Vincent, 2011; Entwistle et al., 2010; Hurst, 2001; Scott et al., 2016). A patient’s intention to engage in safety efforts may also be affected by the perception that clinicians expect and would approve of such behaviors (Schwappach & Wernli, 2011; Scott et al., 2016).

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its small sample and single-institution setting, and the fact that parents who were available for interviews were English speaking, able to spend considerable time at the bedside, and predominantly identified as White (74%). Parents who identify as being from other racial or ethnic backgrounds; who are not able to be present in the NICU as much; or who are not fluent in English may have very different concerns and experiences regarding communication. However, the consistency of our findings with other studies involving parents and patients suggests some transferability.

Conclusion

In summary, parents have safety concerns that they may not always report to clinicians. Parents assess situations and balance the perceived benefits and risk of raising their safety concerns with clinical providers. Some parents find speaking up very difficult even when a threat seems clear. Our study supports the need for interventions aimed at speaking up and promoting patient engagement in patient safety to integrate patient perspectives from the design stage forward. The encouragement granted by large scale patient and family engagement in safety campaigns will likely be ineffective without local involvement from patient/parent stakeholders, and consistent reinforcement that such engagement is not only welcomed (Entwistle et al., 2005) but that safety is co-produced by clinicians and parents and that speaking up will not lead to negative consequences (Entwistle et al., 2010; Hurst, 2001; Rhodes, McDonald, Campbell, Daker-White, & Sanders, 2015; Rosenberg et al., 2016)

Table 3.

Selected Participant Demographics

| Parent Characteristics | N = 46 |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| White | 34 (74%) |

| Asian | 2 (4%) |

| Black | 1 (2%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (2%) |

| Not reported | 8 (18%) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 17(37%) |

| Education | |

| High school | 7 (15%) |

| College | 30 (65%) |

| Graduate school | 9 (20%) |

| Occupation | |

| Service/Technical | 25 (54%) |

| Professional/Manager | 10 (22%) |

| Homemaker | 6 (13%) |

| Not given | 5 (11%) |

|

| |

| Characteristics of the parents’ hospitalized newborns

| |

| Inborn | 34 (74%) |

| Expected Admission | 28 (62%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Prematurity | 16 (35%) |

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia | 8 (17%) |

| Cardiac defect | 6 (13%) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 34.4 (±4.3) |

| Length of stay at enrollment (days) | 32.7 (±19.5) |

From Parents’ perspectives on safety in neonatal intensive care: a mixed-methods study. A. Lyndon, C. H. Jacobson, K. M. Fagan, K. Wisner, and L.S. Franck, BMJ Quality and Safety, 23 (11), 902–9, 2014. Adapted with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Callouts.

The purpose of this study was to learn about parents’ communication of safety concerns in the NICU.

Parents found speaking up about safety concerns to be a socially complex process; this process was difficult for some parents to manage.

Stronger appreciation is needed by clinicians and hospital systems of how integral the patient experience is to patient safety.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI KL2TR000143, and the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses/March of Dimes Foundation Margaret Comerford Freda Research Grant. The study was also supported in part by a training grant (T32 NR07088) from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research. The contents of the publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, AWHONN, or the March of Dimes. The authors thank the clinical research nurses for their assistance with study recruitment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Contributor Information

Audrey Lyndon, Department of Family Health Care Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco CA.

Kirsten Wisner, Department of Family Health Care Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco CA.

Carrie Holschuh, School of Nursing, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA.

Kelly M. Fagan, Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

Linda S. Franck, Department of Family Health Care Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA.

References

- Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014;23:548–555. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun VB, Clark V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Jacklin R, Vincent CA. An examination of opportunities for the active patient in improving patient safety. Journal of Patient Safety. 2012;8:36–43. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31823cba94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Pinto A, Darzi A, Vincent CA. Patients’ attitudes towards patient involvement in safety interventions: results of two exploratory studies. Health Expectations. 2013;16:e164–e176. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Vincent CA. Patient involvement in patient safety: How willing are patients to participate? BMJ Quality and Safety. 2011;20:108–114. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Savvopoulou M, Shergill R, Shergill S, Schwappach D. Predictors of healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards family involvement in safety-relevant behaviours: a cross-sectional factorial survey study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005549. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donetto S, Tsianakas V, Robert G. Using experience-based co-design to improve the quality of healthcare: mapping where we are now and establishing future directions. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.kcl.ac.uk/nursing/research/nnru/publications/reports/ebcd-where-are-we-now-report.pdf.

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle VA, McCaughan D, Watt IS, Birks Y, Hall J, Peat M Grp, Pips. Speaking up about safety concerns: Multi-setting qualitative study of patients’ views and experiences. Quality & Safety In Health Care. 2010;19:e33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.039743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle VA, Mello MM, Brennan TA. Advising patients about patient safety: current initiatives risk shifting responsibility. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2005;31:483–494. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31063-4. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16255326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerhaugh SY, Strauss A, Suczeck B, Wiener CL. Hazards in hospital care: Ensuring patient safety. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst I. Vigilant watching over: Mothers’ actions to safeguard their premature babies in the newborn intensive care nursery. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;15:39–57. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

- Khan A, Furtak SL, Melvin P, Rogers JE, Schuster MA, Landrigan CP. Parent-reported errors and adverse events in hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016;170:e154608. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kools S, McCarthy M, Durham R, Robrecht L. Dimensional Analysis: Broadening the Conception of Grounded Theory. Qualitative Health Research. 1996;6:312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kugelman A, Inbar-Sanado E, Shinwell ES, Makhoul IR, Leshem M, Zangen S, Bader D. Iatrogenesis in neonatal intensive care units: observational and interventional, prospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2008;122:550–555. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard MW, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i85–i90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A. Social and environmental conditions creating fluctuating agency for safety in two urban academic birth centers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37:13–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Jacobson CH, Fagan KM, Wisner K, Franck LS. Parents’ perspectives on safety in neonatal intensive care: A mixed-methods study. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2014;23:902–909. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Kennedy HP. Perinatal safety: From concept to nursing practice. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2010;24:22–31. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181cb9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon A, Sexton JB, Simpson KR, Rosenstein A, Lee KA, Wachter RM. Predictors of likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in labour and delivery. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2012;21:791–799. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2010-050211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HM, Navne LE, Lipczak H. Involvement of patients with cancer in patient safety: A qualitative study of current practices, potentials and barriers. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2013;22:836–842. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer M, Dardess P, Carman KL, Frazier K, Smeeding L. Guide to patient and family engagement: Environmental scan report. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/ptfamilyscan/ptfamilyscan.pdf.

- Mohsin-Shaikh S, Garfield S, Franklin BD. Patient involvement in medication safety in hospital: an exploratory study. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. 2014;36:657–666. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9951-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A, editor. Keeping patients safe: Transforming the work environment of nurses. 2004 Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/10851/chapter/1#ii. [PubMed]

- Raemer DB, Kolbe M, Minehart RD, Rudolph JW, Pian-Smith MC. Improving anesthesiologists’ ability to speak up in the operating room: A randomized controlled experiment of a simulation-based intervention and a qualitative analysis of hurdles and enablers. Academic Medicine. 2016;91:530–539. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju TN, Suresh G, Higgins RD. Patient safety in the context of neonatal intensive care: Research and educational opportunities. Pediatric Research. 2011;70:109–115. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182182853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rance S, McCourt C, Rayment J, Mackintosh N, Carter W, Watson K, Sandall J. Women’s safety alerts in maternity care: is speaking up enough? BMJ Quality and Safety. 2013;22:348–355. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes P, McDonald R, Campbell S, Daker-White G, Sanders C. Sensemaking and the co-production of safety: a qualitative study of primary medical care patients. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2016;38:270–285. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg RE, Rosenfeld P, Williams E, Silber B, Schlucter J, Deng S, Sullivan-Bolyai S. Parents’ perspectives on “keeping their children safe” in the hospital. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2016;31:318–326. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L. Dimensional analysis: notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In: Maines DR, editor. Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of anselm strauss. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1991. pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach DL. Engaging patients as vigilant partners in safety: A systematic review. Medical Care Research and Review. 2010;67:119–148. doi: 10.1177/1077558709342254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach DL, Gehring K. Trade-offs between voice and silence: A qualitative exploration of oncology staff’s decisions to speak up about safety concerns. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:303. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach DL, Wernli M. Barriers and facilitators to chemotherapy patients’ engagement in medical error prevention. Annals of Oncology. 2011;22:424–430. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Heavey E, Waring J, Jones D, Dawson P. Healthcare professional and patient codesign and validation of a mechanism for service users to feedback patient safety experiences following a care transfer: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011222. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharek PJ, Horbar JD, Mason W, Bisarya H, Thurm CW, Suresh G, Classen D. Adverse events in the neonatal intensive care unit: development, testing, and findings of an NICU-focused trigger tool to identify harm in North American NICUs. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1332–1340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson KR, Knox GE. Adverse perinatal outcomes: Recognizing, understanding, and preventing common types of accidents. Lifelines. 2003;7:224–235. doi: 10.1177/1091592303255715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak JE. Infections and interaction rituals in the organisation: Clinician accounts of speaking up or remaining silent in the face of threats to patient safety. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2016;38:325–339. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. Facts about speak up intitiatives. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Speak_Up.pdf.

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel event data: Root causes by event type 2004-2015. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Event_type_2Q_2015.pdf.

- The King’s Fund. Experience-based co-design toolkit. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/ebcd.

- Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010;16:837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]