Abstract

In this study we examine relationships between traditional cultural factors, apathy, and health-related outcomes among a sample of American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. Participants completed cross-sectional interviewer-assisted paper and pencil surveys. We tested a proposed model using latent variable path analysis in order to understand the relationships between cultural participation, apathy, frequency of high blood sugar symptoms, and health-related quality of life. The model revealed significant direct effects from cultural participation to apathy, and apathy to both health-related outcomes. No direct effect of cultural participation on either health-related outcome was found; however, cultural participation had a negative indirect effect through apathy on high blood sugar and positive indirect effects on health-related quality of life. This study highlights a potential pathway of cultural involvement to positive diabetes outcomes.

Keywords: Apathy, community-based participatory research, culture, type 2 diabetes mellitus, American Indians

American Indian and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) in the United States experience a 2.1 times higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes than non-Hispanics Whites,1 and a rate of diabetes-related deaths 177% greater than the general population.2 While disease management is paramount to improving diabetes control and decreasing the associated risks of additional health complications, mental and emotional health problems play a key role in disrupting the management of diabetes.3–7 Often, AI communities endure disproportionate rates of both mental and physical health problems,8 viewed by many as consequences of cultural disruption and loss due to colonization, forced relocation, and attacks and prohibition of cultural and spiritual practices.9,10 To correct this imbalance, participation in AI cultural and spiritual activities may be a key to preventing chronic illness and mental health problems, and promoting positive outcomes for those with these diseases.11,12 In this study, we explore the relationships between cultural and spiritual activity participation, apathy, and health outcomes among AI adults with type 2 diabetes.

Identification with, participation within, and connection to one’s AI culture is related to positive mental and physical health in a number of published studies.13–22 Culturally-salient constructs of relevance to many Indigenous communities and connected to health in these studies included participation in traditional cultural and land-based activities, subsistence practices, cultural spirituality and spiritual orientation, adolescent interest in learning about culture, and level of “traditionalism.” Further, a systematic review on nutrition-based interventions for individuals with metabolic syndrome identified cultural adaption as one factor that may improve the efficacy of an intervention.22 The potentially protective effects of culture are included in the Indigenist stress coping model, a theoretical framework postulated by Walters, Simoni, and Evans-Campbell.23 The model suggests that the associations between trauma, life stressors, and adverse health outcomes among AI community members are moderated by cultural factors such as spirituality and traditional healing practices and builds on stress process perspectives in which person factors and environmental contexts serve as mediators or moderators of stressful life events; health outcomes depend in part on coping resources and responses to life stressors.24,25 The Indigenist stress coping model is tailored towards unique cultural and socio-historical factors salient to AI populations. The underlying notion that cultural factors influence health processes26 forms the basis for this study.

We have previously shown that depressive symptoms, anxiety, and apathy are correlated with hyperglycemia, increased comorbidities, and activity impairment in a population of AI people living with diabetes.7 Others have documented a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and mental health symptoms like depression and anxiety,4 but very little is known about the relationship between diabetes and apathy. Apathy includes a lack of motivation, evidenced by diminished goal-directed behavior, cognition or emotion relative to previous functioning.27 This type of behavior can impair a person’s ability to maintain the sometimes labor intensive process of managing diabetes. Prior literature has demonstrated that apathy-like behaviors such as a lack of desire to learn and lack of interest act as barriers to attendance at diabetes education programs,28 and follow-up dilated eye examinations.29 In a diabetes self-management program, apathy was a predisposing factor resulting in program attrition.30 Apathy is also related to diabetes control and self-care (i.e., increased hemoglobin A1C values, higher body mass index, lower adherence to exercise programs and insulin regimen).5,6 Thus, it appears apathy plays an important role in the life of diabetes patients influencing both their diabetes outcomes and their overall wellbeing.

Diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in many AI communities, yet studies identifying mechanisms of diabetes management and outcomes have mainly been limited to non-AI samples; the relationship of apathy in particular to diabetes outcomes is underexplored in AI communities. Further, a growing body of research demonstrates the protective effects of traditional activities and spirituality on aspects of health within AI communities, but more studies are needed. We focus on these gaps in the literature. Based on prior research and the Indigenist stress coping model, and while controlling for a number of demographic variables, we hypothesize:

-

H1

Cultural participation will be negatively related to apathy.

-

H2

Apathy will be positively associated with high blood sugar, and negatively associated with health-related quality of life.

-

H3

Cultural participation will be negatively related to high blood sugar, and a positively related to health-related quality of life.

-

H4

Finally, cultural participation will be indirectly associated with improved diabetes outcomes through its negative association with apathy.

Methods

Research design

The Mino Giizhigad (A Good Day) Study is a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project with the Lac Courte Oreilles and Bois Forte Bands of Chippewa (although many tribal members prefer the term Anishinaabe or Ojibwe, the term Chippewa has been used in relatively recent legal proceedings and is currently incorporated into a number of Band names31) and the University of Minnesota Medical School-Duluth campus. Community-based participatory research is an orientation that changes the role of researcher and “researched,” such that research communities become equal participants in a mutually beneficial process.32 The key steps in community-based participatory research/tribally-based research are (1) building and maintaining collaborative relationships, (2) planning the research together, (3) implementing and evaluating the research in culturally acceptable ways, and (4) disseminating the findings from a tribal perspective.33 Prior research with AI communities has resulted in some cases in exploitation and stereotyping of AI groups or individuals,34 consequently creating wariness of outside researchers. A CBPR orientation minimizes potential harmful consequences by considering the unique ethical situation presented by the history and sovereignty of AI nations.

Tribal resolutions from both communities were obtained prior to application submission for funding and the project officially launched with community feasts where we discussed the study goals, obtained community feedback, and established Community Research Councils (CRC). Community Research Council and university team members were engaged together throughout the duration of the project, from methodological planning to final data collection and analysis. The University of Minnesota IRB and Indian Health Services National IRB reviewed and approved the study methodology.

Sample

Potential participants were randomly selected from each reservation’s health clinic records. Inclusion criteria were patients 18 years or older, with a type 2 diabetes diagnosis, and self-identifying as AI. Clinic partners generated a simple random sample of 150 patients from their clinic records. Selected patients were mailed a welcome letter, an informational project brochure, and a contact information card with mail and phone-in options to decline participation. Trained community interviewers contacted non-declining recruits to schedule interviews. Consenting participants were given a pound of locally cultivated wild rice and a $30 cash incentive. Paper-and-pencil interviewer administered surveys were completed in participants’ location of choice, most Often in private spaces within homes. The time to complete each survey ranged from approximately 1.5 to 3 hours. Out of an eligible sample of 289 individuals, 218 participants completed surveys for a study response rate of 75.4%.

Measures

AI cultural involvement. Two measures of traditional AI cultural involvement were included in this study: spiritual activities and traditional activities. Participation in spiritual activities was measured with responses to a nine-item spiritual activities measure. Respondents read a list of spiritual activities, and were asked if they had participated in each activity within the last 12 months. Representative items from the index include “Use of traditional medicine,” “Sought advice from a spiritual advisor,” and “Participated in a sweat” (a traditional ceremony). “Yes” responses were given a score of 1 (no = 0). Responses to all 9 items were summed for an overall score with a possible range of 0–9). Participation in traditional activities was measured with responses to an 18-item traditional activities scale following the same scoring procedure (range = 0–18). Representative items include “Been to a powwow,” “Done any beading,” “Gone ricing,” and “Listened to elders tell stories.” Cronbach’s α for spiritual activities and traditional activities scales were .79 and .77, respectively.

Apathy was measured with responses to seven items adapted from the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES).35 Adaptations were made based on feedback from CRCs on issues related to validity and comprehension. Participants were asked to indicate frequency (from “not at all” to “a lot”) during the four weeks prior to the interview of various thoughts, feelings, and activities indicating apathy (e.g., interest in new experiences, approaching life with intensity, having motivation), with higher scores indicating a greater degree of apathy (range = 0–21). Cronbach’s α for the resulting summed index = .73.

Participants were asked how they would rate their general health status as a proxy for health-related quality of life. Responses were coded from 0 (poor) to 4 (excellent). High blood sugar was measured by asking participants how many days in the past month they had high blood sugar, with symptoms such as thirst, dry mouth and skin, increased sugar in the urine, less appetite, nausea, or fatigue. Responses were 0 times (0), 1–3 times (1), 4–6 times (2), 7–12 times (3), and more than 12 times (4).

Several control variables were also included. Gender was coded 0 = male, 1 = female. Although all participants in this study sought medical care at clinics located on reservation, some lived off reservation lands. This was controlled for with a dummy variable, on/off reservation, where 0 = off reservation, and 1 = on reservation. A tribal location variable was created to control for differences between locations; participants belonging to community 1 = 0, community 2 = 1. Per capita household income was measured by asking respondents to indicate their overall household income within $10,000 ranges. The final measure included the midpoints of these ranges divided by the number of people living within households. The number of years living with diabetes and self-reported age was also controlled for. Due to the potential overlap between depression and apathy (e.g., apathy is associated with depression36,37,38) we controlled for the presence of depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).37 Participants reported if they had been bothered by symptoms of depression over the past two weeks (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, and 3 = almost every day), with a possible range from 0 to 27. We used a cutoff score of 10 or higher to indicate the presence of clinically meaningful depressive symptoms.39,40 Finally, we controlled for comorbidities. We assessed comorbidities by asking a battery of questions from the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center’s Diabetes History form (DMH). Participants were asked if a health care provider had ever told them that they had specific conditions (e.g., heart attack, hypertension, amputation). A count of comorbid conditions was calculated by summing the affirmative responses to each condition.

Analysis plan

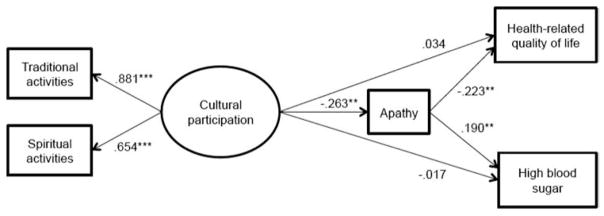

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 20),41 and MPlus42 to explore the relationship between study variables. We ran a latent variable path analysis with MPlus to evaluate the proposed structural relationships and to investigate the direct and indirect effects of cultural participation and apathy on diabetes outcomes, while controlling for age, gender, years with diabetes, income, study location, living on reservation land, and depressive symptoms. Missing data for endogenous variables were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation, and deletion of cases with missing information on exogenous variables (i.e., control variables) resulted in 211 observations. Statistical significance was set at a level of .05, and p-values were calculated using the Delta method for parameter estimates in the path analysis. We also used nonparametric case-based bootstrapping (r = 2000) to calculate 95% confidence intervals, confirming the significance of estimates including the indirect effects. Our study model is shown in Figure 1. Cultural participation is a latent variable with two measured indicators, traditional activities, and spiritual activities. Cultural participation has a direct path to apathy, and both cultural participation and apathy have direct paths to the two outcome variables. Control variables (not shown in the model) have direct paths to cultural participation, apathy, and the two outcome variables. Model fit was assessed using criteria suggested by Hu and Bentler,43 where values of standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR) should be less than or equal to 0.08, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be less than or equal to 0.06, and comparative fit index (CFI) should be greater than or equal to 0.95.

Figure 1.

Latent-variable path analysis with standardized path coefficients, controlling for age, gender, years with diabetes, income, study location, living on reservation land, number of comorbid conditions, and depressive symptoms.

** p < .01

*** p < .001

Results

Participant characteristics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 1. Participants were on average 56 years old with a per capita household income of $10,486, had diabetes for nearly 15 years, and had approximately four comorbid medical conditions. Over half were female (55.5%), and the majority lived on reservation lands (76.8%). Participants’ scores ranged from 0 to 19 on the summed adapted apathy scale, with a mean of 6.1. The mean traditional activities score was 6.1, with individual values ranging from 2 to 17. The spiritual activities scores ranged from 0 to 9, with a mean of 2.7. Over half (53.7%) of the participants had at least one instance of high blood sugar in the past month, and 38.9% reported fair or poor health-related quality of life.

Table 1.

BIVARIATE COORELATIONS AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR ALL STUDY VARIABLES

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Apathy | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Spiritual Activities | −.17 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3. Traditional Activities | −.20 | .58 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4. High Blood sugar | .23 | .01 | −.03 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5. Health-related quality of life | −.30 | .00 | .06 | −.29 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6. Years living with diabetes | .05 | −.08 | −.15 | .09 | −.10 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7. Gender (female = 1) | −.13 | .13 | −.06 | .01 | −.05 | .08 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8. Age | .03 | −.11 | −.14 | −.25 | .12 | .33 | .10 | 1.00 | |||||

| 9. Income ($) | −.16 | −.02 | −.01 | .02 | .16 | .03 | .02 | .10 | 1.00 | ||||

| 10. On reservation | .10 | .06 | .00 | .10 | −.02 | .14 | .03 | −.02 | −.18 | 1.00 | |||

| 11. Tribal location (location 2 = 1) | −.16 | .04 | −.03 | .03 | −.05 | −.01 | .02 | −.03 | .04 | −.30 | 1.00 | ||

| 12. Comorbidities | .15 | .04 | −.09 | .11 | −.15 | .15 | .09 | .34 | .04 | −.06 | .10 | 1.00 | |

| 13. Depressive symptoms | .13 | .11 | .11 | .23 | −.32 | .01 | .02 | −.20 | −.13 | −.06 | .08 | .05 | 1.00 |

| Means/% (standard deviation) | 6.1 (3.8) | 2.7 (2.2) | 6.1 (3.1) | 1.1 (1.3) | 1.7 (0.96) | 14.1 (12.2) | 55.5% | 56.1 (13.5) | 10,486 (9,408) | 76.8% | 54.5% | 3.9 (2.5) | 16.6% |

Bivariate results

In bivariate analyses (Table 1), spiritual activities and traditional activities scores were negatively associated with apathy (r = −.17; p < .05 and r = −.20; p < .01 respectively). Traditional activities scores were also negatively associated with participant’s age and years living with diabetes (both, r = −.15; p < .05). Spiritual activities and traditional activities scores were positively associated with one another (r = .58; p < .001). Apathy was significantly related to high blood sugar (r = .23; p < 0.01) and health-related quality of life (r = −.30, p < .001). High blood sugar was also related to depressive symptoms (r = .23; p < .01), and negatively associated with health-related quality of life (r = −.29; p < .001) and age (r = −.25; p < .001). Health-related quality of life was positively associated with income (r = .16; p < .05), and negatively associated with number of comorbid health conditions (r = −.15; p < .05) and depressive symptoms (r = −.32; p < .001).

Latent variable path analysis of cultural participation, apathy, and health

To assess the direct and indirect effects of cultural participation on diabetes outcomes, our proposed model (Figure 1) was evaluated using latent variable path analysis. The chi-square test of model fit was 16.390 (degrees of freedom 10, p = .089), indicating good fit. The SRMR was 0.020, RMSEA was 0.055 (90% CI, 0.000–0.101), and CFI was 0.97, all suggesting acceptable fit. Both factor loadings for the latent variable cultural participation were significant (p < .001). The variables in the model described 20.6% of the variation in high blood sugar, and 21.1% of the variation in health-related quality of life. Figure 1 shows the standardized estimates. Cultural participation, female gender, and study location 2 were associated with lower apathy, while number of comorbidities and depressive symptoms were associated with higher apathy. High blood sugar was positively related to apathy, number of years with diabetes, number of comorbidities, and negatively related to age. Health-related quality of life was positively related to age, and negatively related to apathy, number of comorbidities, and depressive symptoms. Cultural participation did not have significant direct effects on the diabetes-related outcomes, but did have significant indirect effects through apathy. Cultural participation had a negative indirect relationship with high blood sugar (−.063; 95% CI −.179 to −.015), and positive indirect relationship with health-related quality of life (.055; 95% CI .014 to .132). Table 2 provides factor loadings, path coefficients, covariances, and indirect effects from the latent variable path analysis.

Table 2.

RESULTS OF LATENT VARIABLE PATH ANALYSIS AND DECOMPOSITION OF EFFECTS

| Cultural participation

|

Apathy

|

High blood sugar

|

Health-related quality of life

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) |

95% CI | Standardized estimate |

Estimate (SE) |

95% CI | Standardized estimate |

Estimate (SE) |

95% CI | Standardized estimate |

Estimate (SE) |

95% CI | Standardized estimate |

|

| Factor loadings | ||||||||||||

| Traditional activities | 2.62 (.61) | (1.39, 11.20) | .88*** | |||||||||

| Spiritual activities | 1.40 (.32) | (.41, 3.11) | .65*** | |||||||||

| Path coefficients | ||||||||||||

| Age | −.01 (.01) | (−.02, .01) | −.08 | .00 (.02) | (−.04, .04) | .01 | −.03 (.01) | (−.05, −.02) | −.35*** | .01 (.01) | (.00, .02) | .17* |

| Gender (female) | −.01 (.24) | (−.39, .44) | .00 | −1.17 (.51) | (−2.11, −.24) | −.15* | .08 (.17) | (−.24, .42) | .03 | −.13 (.12) | (−.36, .11) | −.07 |

| Years with diabetes | −.01 (.01) | (−.03, .00) | −.14 | −.01 (.02) | (−.05, .03) | −.02 | .02 (.01) | (.00, .03) | .15* | −.01 (.01) | (−.02, .00) | −.11 |

| Income | .00 (.01) | (−.01, .02) | .02 | −.05 (.03) | (−.10, .01) | −.12 | .02 (.01) | (−.01, .03) | .11 | .01 (.01) | (.00, .02) | .10 |

| Study location | −.04 (.18) | (−.35, .28) | −.02 | −1.33 (.50) | (−2.29, −.38) | −.17** | .13 (.17) | (−.23, .46) | .05 | −.10 (.13) | (−.36, .16) | −.05 |

| Living on reservation land | .09 (.22) | (−.33, .63) | .04 | .59 (.61) | (−.61, 1.66) | .07 | .33 (.21) | (−.03, .73) | .11 | .02 (.15) | (−.28, .31) | .01 |

| Comorbidities | −.01 (.04) | (−.08, .06) | −.03 | .24 (.10) | (.05, .43) | .16* | .09 (.03) | (.02, .16) | .17* | −.05 (.03) | (−.10, .00) | −.14* |

| Depressive symptoms | .35 (.22) | (.02, .95) | .13 | 2.67 (.67) | (1.01, 4.37) | .26*** | .42 (.24) | (−.09, .93) | .12 | −.56 (.17) | (−.91, −.22) | −.22** |

| Cultural participation | −.98 (.31 | (−1.72, −.29) | −.26** | −.02 (.10) | (−.21, .12) | −.02 | .03 (.07) | (−.08, .20) | .03 | |||

| Apathy | .07 (.02) | (.01, .11) | .19** | −.06 (.02) | (−.09, −.02) | −.22** | ||||||

| Covariance | ||||||||||||

| High blood sugar | −.15 (.07) | (−.30, −.02) | −.16* | |||||||||

| Indirect effects | ||||||||||||

| Cultural participation through apathy | −.06 (.03) | (−.18, −.02) | −.05* | .06 (.02) | (.01, .13) | .06* | ||||||

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < 0.001;

SE = Standard Error; CI = Confidence Interval

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between AI cultural factors, apathy and diabetes-related outcomes in two AI communities. While apathy has been linked to diabetes-related health outcomes previously,5,6 its relationship to traditional and cultural participation for AI patients living with diabetes is unique to our study. Participation in cultural activities may provide a sense of belonging to something larger than the individual and also give a feeling of connectedness to those who participate. These factors may help explain the mechanism by which cultural participation seems to serve as a mediating factor in achieving better health outcomes among AI people.

We found support for three of our four hypotheses. As we predicted, (H1), participants who reported more involvement in cultural and traditional activities were significantly less likely to indicate feelings of apathy. We also found support for H2 indicating a positive relationship between apathy and high blood sugar symptoms and negative association between apathy and health-related quality of life. Contrary to our third prediction (H3), cultural spiritual and traditional activities were not directly related to reports of high blood sugar or quality of life; however, these cultural factors did have protective effects on diabetes-related health outcomes indirectly by way of a negative association with apathy (H4). These findings persisted even affer accounting for participant’s age, gender, per capita household income, tribal affiliation, study location, living on or off reservation lands, depressive symptoms, and comorbid medical conditions. It is notable that apathy continued to be significantly related to diabetes outcomes even after depression was accounted for, which extends previous works demonstrating links between apathy and many aspects of diabetes management.5,6,30

The significant associations between apathy and worse diabetes outcomes suggest that interventions/treatments to reduce apathy may be an important component of diabetes care.22 We found that participation in traditional AI cultural activities is indirectly associated with better diabetes-related outcomes via lower levels of apathy. Thus, increased focus on culturally-specific, culturally safe care44 and support of community efforts to increase access and involvement in AI cultural activities may have important health benefits for those living with diabetes, and could be integral to apathy reduction goals. The potential for AI cultural involvement to promote health is consistent with the Indigenist stress coping model13 and a growing body of literature demonstrating protective associations between AI cultural factors and overall self-rated health status,22 and physical health.20,21

When considering limitations of our study it is important to discuss issues of generalizability. We only sampled two reservations; therefore it would be inappropriate to apply our results to all 566 federally recognized tribes45 given the great diversity in cultural practices and health statuses across tribal groups. Still, this within-culture study has implications for understanding the imperative role of cultural contexts for health in any community.46 In addition, our cross-sectional design restricts conclusions regarding causal ordering of the associations between apathy, cultural participation, and diabetes outcomes.

Our study reveals linkages between cultural participation, apathy, and diabetes-related outcomes among AI adults. Given the powerful role of culture in health,26 further investigation aimed at understanding the mechanism(s) by which various cultural factors influence health is needed. Longitudinal studies could validate these findings by ascertaining the relation of cultural participation, apathy, and outcomes over time. It has long been known within communities that culture can be utilized as a tool for promoting health; this study and others like it are helping to produce empirical evidence on par with community perspectives.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant (MH085852), M. Walls, Principal Investigator and Pathways to Advanced Degrees in Life Sciences grant (GM086669). The contents of this manuscript are produced by the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. B. Aronson gratefully acknowledges support from an American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education Fellowship and a Health Services Dissertation Award (R36) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R36HS024180-01).

The authors would like to thank Community Research Council members: Doris Isham, Julie Yaekeal-Black Elk, Tracy Martin, Sidnee Kellar, Robert Miller, Geraldine Whiteman, Peggy Connor, Michael Conner, Stan Day, Pam Hughes, Jane Villebrun, Muriel Deegan, Beverly Steel, and Ray Villebrun.

Contributor Information

Amanda E. Carlson, University of Minnesota, Duluth, College of Education and Human Service Professions, and was a research assistant in the Department of Biobehavioral Health and Population Sciences, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus.

Benjamin D. Aronson, Assistant Professor of Social and Administrative Pharmacy, Ohio Northern University.

Michael Unzen, Graduate student at the University of Minnesota, Duluth, College of Education and Human Service Professions.

Melissa Lewis, Assistant Professor in the Department of Biobehavioral Health and Population Sciences, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus.

Gabrielle J. Benjamin, Alumni member of the University of Minnesota, Duluth

Melissa L. Walls, Associate Professor in the Department of Biobehavioral Health and Population Sciences, University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Indian Health Service. Trends in Indian health: 2014 edition. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. (4) Foundations of care: education, nutrition, physical activity, smoking cessation, psychosocial care, and immunization. Diabetes Care. 2015 Jan;38( Suppl):S20–30. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S007. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc15-S007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001 Jul-Aug;63(4):619–30. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padala PR, Desouza CV, Almeida S, et al. The impact of apathy on glycemic control in diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008 Jan;79(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.06.012. Epub 2007 Aug 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce DG, Nelson ME, Mace JL, et al. Apathy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;23(6):615–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.09.010. Epub 2014 Oct 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walls ML, Aronson BD, Soper GV, et al. The prevalence and correlates of mental and emotional health among American Indian adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014 May;40(3):319–28. doi: 10.1177/0145721714524282. Epub 2014 Feb 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721714524282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Indian Health Service. Indian health disparities. Rockville, MD: Indian Health Service; 2015. Available at: https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/includes/themes/newihstheme/display_objects/documents/factsheets/Disparities.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenfeld PJ. Indigenous peoples and diabetes: community empowerment and wellness. In: Ferreira ML, Lang GC, editors. Diabetes among the Pima: stories of survival by Carolyn Smith-Morris. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1. Vol. 22. 2008. Mar, pp. 121–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet. 2009 Jul 4;374(9683):76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gone JP. Redressing First Nations historical trauma: theorizing mechanisms for indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013 Oct;50(5):683–706. doi: 10.1177/1363461513487669. Epub 2013 May 28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461513487669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson K, Olson S. Leveraging culture to address health inequalities: examples from Native communities: workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald JP, Ford JD, Willox AC, et al. A review of protective factors and causal mechanisms that enhance the mental health of Indigenous Circumpolar youth. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013 Dec 9;72:21775. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21775. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garroutte EM, Goldberg J, Beals J, et al. Spirituality and attempted suicide among American Indians. Soc Sci Med. 2003 Apr;56(7):1571–9. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00157-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeCou CR, Skewes MC, López ED. Traditional living and cultural ways as protective factors against suicide: perceptions of Alaska Native university students. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013 Aug;5:72. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.20968. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v72i0.20968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pu J, Chewning B, St Clair ID, et al. Protective factors in American Indian communities and adolescent violence. Matern Child Health J. 2013 Sep;17(7):1199–207. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1111-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitbeck LB, McMorris BJ, Hoyt DR, et al. Perceived discrimination, traditional practices, and depressive symptoms among American Indians in the upper midwest. J Health Soc Behav. 2002 Dec;43(4):400–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson K, Rosenberg MW. Exploring the determinants of health for First Nations peoples in Canada: can existing frameworks accommodate traditional activities? Soc Sci Med. 2002 Dec;55(11):2017–31. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00342-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coe K, Attakai A, Papenfuss M, et al. Traditionalism and its relationship to disease risk and protective behaviors of women living on the Hopi reservation. Health Care Women Int. 2004 May;25(5):391–410. doi: 10.1080/07399330490438314. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330490438314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dill EJ, Manson SM, Jiang L, et al. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss among American Indian and Alaska Native participants in a diabetes prevention translational project. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:1546939. doi: 10.1155/2016/1546939. Epub 2015 Nov 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oster RT, Grier A, Lightning R, et al. Cultural continuity, traditional Indigenous language, and diabetes in Alberta First Nations: a mixed methods study. Int J Equity Health. 2014 Oct 19;13:92. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0092-4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0092-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nava LT, Zambrano JM, Arviso KP, et al. Nutrition-based interventions to address metabolic syndrome in the Navajo: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2015 Nov;24(21–22):3024–45. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12921. Epub 2015 Aug 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance use among American Indians and Alaska natives: incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping paradigm. Public Health Rep. 2002;117( Suppl 1):S104–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinges NG, Joos SK. Stress, coping, and health: models of interaction for Indian and native populations. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res Monogr Ser. 1988;1:8–64. doi: 10.5820/aian.mono01.1988.8. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.mono01.1988.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29(2):295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. https://doi.org/10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagawa-Singer M, Dressler WW, George SM, et al. The cultural framework for health: an integrative approach for research and program evaluation. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; 2014. Available at: https://www.countyofsb.org/behavioral-wellness/asset.c/2609. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin RS, Wilkosz PA. Disorders of diminished motivation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005 Jul-Aug;20(4):377–88. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200507000-00009. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graziani C, Rosenthal MP, Diamond JJ. Diabetes education program use and patient-perceived barriers to attendance. Fam Med. 1999 May;31(5):358–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puente BD, Nichols KK. Patients’ perspectives on noncompliance with retinopathy standard of care guidelines. Optometry. 2004 Nov;75(11):709–16. doi: 10.1016/s1529-1839(04)70223-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1529-1839(04)70223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gucciardi E, DeMelo M, Oftenheim A, et al. Factors contributing to attrition behavior in diabetes self-management programs: a mixed method approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008 Feb 4;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treuer A. Ojibwe in Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baldwin JA, Johnson JL, Benally CC. Building partnerships between indigenous communities and universities: lessons learned in HIV/AIDS and substance abuse prevention research. Am J Public Health. 2009 Apr;99( Suppl 1):S77–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.134585. Epub 2009 Feb 26. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.134585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, et al. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008 Aug;98(8):1398–406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. Epub 2008 Jun 12. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991 Aug;38(2):143–62. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-v. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang WK, Lau CG, Mok V, et al. Apathy and health-related quality of life in stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 May;95(5):857–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.012. Epub 2013 Nov 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishizaki J, Mimura M. Dysthymia and apathy: diagnosis and treatment. Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:893905. doi: 10.1155/2011/893905. Epub 2011 Jun 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kronenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Phq-9: validity of a brief depression serverity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilbody S, Richards D, Barkham M. Diagnosing depression in primary care using self-completed instruments: UK validation of PHQ-9 and CORE-OM. Br J Gen Pract. 2007 Aug;57(541):650–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMilan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012 Feb 21;184(3):E191–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. Epub 2011 Dec 19. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multi-disciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. Epub 2009 Nov 3. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown SA, Garcia AA, Kouzekanani K, et al. Culturally competent diabetes self-management education for Mexican Americans: the Starr County border health initiative. Diabetes Care. 2002 Feb;25(2):259–68. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.259. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.U.S. Department of the Interior. Who we are. Washington, DC: Bureau of Indian Affairs; 2017. Available at: https://bia.gov/WhoWeAre/ [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: with special feature on socioeconomic status and health. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus11.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]