Abstract

Avian haemosporidia have been reported in various birds of Japan, which is part of the East Asian-Australian flyway and is an important stopover site for migratory birds potentially carrying new pathogens from other areas. We investigated the prevalence of avian malaria in injured wild birds, rescued in Tokyo and surrounding areas. We also evaluated the effects of migration by examining the prevalence of avian malaria for each migratory status. 475 birds of 80 species were sampled from four facilities. All samples were examined for haemosporidian infection via nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the cytochrome b (cytb) gene. 100 birds (21.1%) of 43 species were PCR positive for avian haemosporidia. Prevalence in wintering birds, migratory breeders, and resident birds was 46.0%, 19.3%, 17.3% respectively. There was a bias in wintering birds due to Eurasian coot (Fulica atra) and Anseriformes. In wintering birds, lineages which are likely to be transmitted by Culiseta sp. in Northern Japan and lineages from resident species of Northern Japan or continental Asia were found, suggesting that wintering birds are mainly infected at their breeding sites. Meanwhile, there were numerous lineages found from resident and migratory breeders, suggesting that they are transmitted in Japan, some possibly unique to Japan. Although there are limits in studying rescued birds, rehabilitation facilities make sampling of difficult-to-catch migratory species possible and also allow for long-term monitoring within areas.

Keywords: Avian haemosporidia, Japan, Rescued wild birds, Migratory birds, Parasite diversity, Cytochrome b

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Prevalence of avian malaria in rescued wild birds in Japan has been demonstrated.

-

•

Many new lineages have been identified, including possibly unique to Japan.

-

•

Rehabilitation facilities allow sampling and monitoring of wild birds possible.

1. Introduction

Avian haemosporidia, including Plasmodium, Haemoproteus, and Leucocytozoon have been reported throughout the world, including Japan (Murata, 2002, Valkiūnas, 2005, Nagata, 2006, Atkinson and Lapointe, 2009, Bueno et al., 2010, Olias et al., 2011, Imura et al., 2012). They are transmitted by blood-feeding vectors, each genus assigned to a different group of arthropod. For example, biting midges (Ceratopogonidae) and louse flies (Hippoboscidae) transmit Haemoproteus, and mosquitoes (Culicidae) and blackflies (Simuliidae) transmit Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon respectively (Valkiūnas, 2005). The distribution of avian haemosporidia is closely linked with the distribution and habitat of the vector (Waldenström et al., 2002, Valkiūnas, 2005) i.e., avian Plasmodium prevalence decreases along with mosquito abundance, in relation to an increase in habitat elevation (Van Riper et al., 1986). Meanwhile, high-altitude forests are a preferred habitat for blackflies and high Leucocytozoon prevalence has been reported among wild birds in this habitat (Imura et al., 2012).

Migratory birds travel long distances between breeding and wintering grounds, and can serve as important carriers of avian malaria (Atkinson and Lapointe, 2009, Garamszegi, 2011). Migratory birds include wintering visitors that spend the winter and breed further north, migrant breeders that breed in the area and winter further south, and passage visitors that breed further north and winter further south. These migratory birds are distinguished from resident breeders, or sedentary birds, which do not migrate and stay in the same area year-round. Japan is a part of the East Asian-Australian Flyway and serves as a breeding ground, wintering ground, and stopover point for various migratory birds, making Japan an important area for ecological studies (Higuchi et al., 2009). Therefore, migratory birds may carry new pathogens from one area to another (Murata, 2007). New parasite lineages may be easily carried into the Kanto area by migratory birds that travel to other areas. Also, both bird and vector distributions have changed in association to global climate change. The rise of air temperature has changed the arrival timing and numbers of migratory birds to their breeding and wintering sites, while in some species the wintering grounds have moved northward (Atkinson and Lapointe, 2009, Higuchi et al., 2009, Garamszegi, 2011, Elbers et al., 2015). Also, various ecological changes have also been reported in the arthropod vectors such as the extension of range, elongation of active period, and increased density due to shortening of developmental period (Atkinson and Lapointe, 2009, Garamszegi, 2011, Elbers et al., 2015). For these reasons, distributions of avian malaria may possibly expand, hence threatening various birds, including endangered species that may be naïve to the pathogen. This suggests that both the prevalence of avian malaria and monitoring of the distribution of birds and vectors are important.

It is often difficult to capture and obtain blood from wild birds. This is a large element as to why the prevalence of avian malaria in various regions and species of Japan are still unstudied. Avian malaria from wild birds has been studied in limited areas such as Hokkaido, Tsushima Island, Minami-Daito Island, Hyogo and some mountains for Japanese rock ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus japonicus) (Murata, 2002, Murata, 2007, Nagata, 2006, Sato et al., 2007, Murata et al., 2007, Murata et al., 2008a, Imura et al., 2012, Tanigawa et al., 2012, Yoshimura et al., 2014), but most areas of Japan are unstudied. In the Kanto region, including Tokyo and the surrounding areas, there are a few facilities that treat and care for injured wild birds. Birds in these facilities are rescued for various reasons such as weakness, concussion and bone fracture due to window collision, car accidents and other causes. These factors might result in poor body conditions and may cause failure in the evaluation of adequate pathogenicity and virulence caused by infection of any haemosporidia. Some birds, including migratory birds, stay in the facility for long terms and migratory evaluations are not always necessarily in the natural state. However, these facilities are a valuable site for studying the prevalence and distribution of avian malaria in the Kanto region. Particularly, these facilities include Anseriformes and Accipitriformes which are both difficult groups of birds to capture. Throughout the year, there is a wide variety of rescued species, both resident and migratory birds, suitable for understanding the diversity of avian malaria in the Kanto area. In this study, we investigated the prevalence of avian malaria in injured and rescued wild birds in the Kanto region. We also evaluated the effect of migration on prevalence by monitoring avian malaria infections in each migratory status such as wintering, breeding and sedentary.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

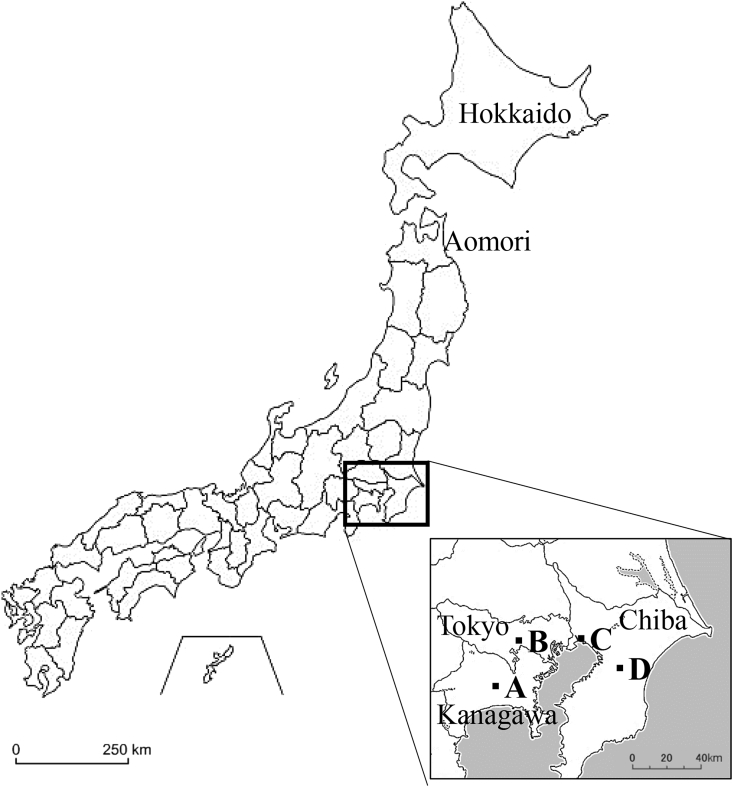

Samples were obtained from 475 birds of 80 species (Table 1), rescued and kept in four facilities: A. Kanagawa Prefecture Natural Conservation Center (35°26′30.2676″N, 139°17′39.8004″E; April 2015 to March 2016), B. Inokashira Animal Hospital (35°41′32.1036″N, 139°34′10.6716″E; December 2013 to March 2015), C. Gyotoku Wild Bird Hospital (35°40′6.024″N, 139°54′56.6964″E; September 2014 to February 2016), D. Bird Clinic Kanesaka Animal Hospital (35°32′39.5268″N, 140°12′50.85″E; August 2013 to March 2015) (Fig. 1). Samples include birds rescued from May 2004 to March 2016. Blood was obtained from either the brachial vein or the jugular vein in live birds. Collected blood samples were kept in microtubes with 70% ethanol at −4 °C until DNA isolation. A portion of the blood was used to make blood smears if possible. The smears were fixed with methanol and then stained with Hemacolor® (Merck KGaA, D-64271 Darmstadt, Germany). After confirming that the smears were dry, each smear was mounted with a cover glass. A small portion of the liver was obtained from dead birds and kept at −20 °C until DNA isolation. All procedures for collecting samples from birds in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Act on Welfare and Management of Animals 1973.

Table 1.

Number of parasite positive birds sampled from the four facilities. The cross (†) indicates species in which at least one individual was infected. Migration status in the Kanto area is shown for each species (W = wintering visitor, S = migrant (summer) breeder, P = passage visitor, R = resident visitor). Number sampled and number of blood smears (in parentheses) are shown, followed by number infected and percentage infected (in parentheses) via PCR. Number infected via PCR are shown for each parasite genera, with each parentheses describing the number infected via microscopy.

| Birds sampled |

Migration status | No. sampled (blood smear) | No. infected by PCR (%) | No. infected by PCR (by microscopy) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Species | Scientific name | Plasmodium | Haemoproteus | Leucocytozoon | Mix | |||

| Anseriformes | Canada goose | Branta canadensis | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tundra swan | Cygnus columbianus | W | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mandarin duck† | Aix galericulata | W | 3(3) | 2 (66.7) | – | – | 2(2) | – | |

| Falcated duck† | Anas falcata | W | 1(0) | 1 (100) | – | – | 1(0) | 1(0) | |

| Mallard† | Anas platyrhynchos | W | 2(2) | 1 (50) | 1(1) | – | – | – | |

| Spot-billed duck | Anas zonorhyncha | R | 9(7) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Northern pintail† | Anas acuta | W | 4(3) | 4 (100) | – | – | 4(3) | – | |

| Common teal† | Anas crecca | W | 3(1) | 3 (100) | – | – | 3(0) | 2(0) | |

| Common pochard† | Aythya ferina | W | 1(1) | 1 (100) | 1(1) | – | – | – | |

| Tufted duck† | Aythya fuligula | W | 6(6) | 2 (33.3) | – | – | 2(2) | – | |

| Greater scaup† | Aythya marila | W | 2(2) | 2 (100) | – | – | 2(2) | – | |

| Galliformes | Bobwhite quail | Colinus virginianus | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Japanese pheasant | Phasianus colchicus | R | 1(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Procellariiformes | Laysan albatross | Phoebastria immutabilis | W | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fork-tailed storm-petrel | Oceanodroma furcata | W | 2(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Streaked shearwater† | Calonectris leucomelas | R | 1(0) | 1 (100) | 1(0) | – | – | – | |

| Short-tailed shearwater | Puffinus tenuirostris | P | 1(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Podicipediformes | Great creasted grebe† | Podiceps cristatus | W | 3(2) | 1 (33.3) | 1(0) | – | 1(0) | 1(0) |

| Black-necked grebe | Podiceps nigricollis | W | 1(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Pelecaniformes | Black-faced spoonbill† | Platalea minor | P | 1(0) | 1 (100) | – | 1(0) | – | – |

| Yellow bittern† | Ixobrychus sinensis | S | 1(0) | 1 (100) | 1(0) | – | – | – | |

| Japanese night heron† | Gorsachius goisagi | S | 1(1) | 1 (100) | – | – | 1(1) | – | |

| Black-crowned night heron† | Nycticorax nycticorax | R | 11(8) | 1 (9.1) | 1(1) | – | – | – | |

| Cattle egret | Bubulcus ibis | S | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Grey heron† | Ardea cinerea | R | 12(4) | 1 (8.3) | – | 1(0) | – | – | |

| Great egret | Ardea alba | R | 2(2) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Intermediate egret | Egretta intermedia | S | 5(4) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Little egret | Egretta garzetta | R | 3(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Suliformes | Great cormorant | Phalacrocorax carbo | R | 15(7) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Accipitriformes | Japanese sparrowhawk | Accipiter gularis | S | 8(6) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Eurasian sparrowhawk | Accipiter nisus | W | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Northern goshawk | Accipiter gentilis | R | 6(4) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Black kite | Milvus migrans | R | 14(9) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Grey-faced buzzard | Butastur indicus | S | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Eastern buzzard | Buteo buteo | W | 3(3) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Gruiformes | Water rail† | Rallus aquaticus | W | 1(0) | 1 (100) | 1(0) | – | – | – |

| Eurasian coot† | Fulica atra | W | 10(8) | 6 (60) | 6(4) | – | – | – | |

| Charadriiformes | Eurasian woodcock† | Scolopax rusticola | W | 3(1) | 2 (66.7) | – | 2(0) | 1(0) | 1(0) |

| Whimbrel† | Numenius phaeopus | S | 1(1) | 1 (100) | – | 1(1) | – | – | |

| Common sandpiper | Actitis hypoleucos | R | 1(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Black-headed gull | Larus ridibundus | W | 2(2) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Black-tailed gull† | Larus crassirostris | R | 6(6) | 3 (50) | – | 3(3) | – | – | |

| Common gull† | Larus canus | W | 1(1) | 1 (100) | – | 1(1) | – | – | |

| Herring gull† | Larus argentatus | W | 9(6) | 1 (11.1) | 1(0) | – | – | – | |

| Colombiformes | Feral pigeon | Columba livia var. domestica | R | 34(26) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Oriental turtle-dove† | Streptopelia orientalis | R | 34(20) | 6 (17.6) | 1(0) | 2(1) | 3(1) | – | |

| White-bellied green-pigeon† | Treron sieboldii | R | 10(9) | 2 (20) | – | – | 2(1) | – | |

| Cuculiformes | Oriental cuckoo | Cuculus optatus | P | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Strigiformes | Sunda scops owl† | Otus lempiji | R | 7(3) | 5 (71.4) | – | 2(0) | 4(2) | 1(0) |

| Ural owl† | Strix uralensis | R | 9(5) | 8 (88.9) | – | 8(4) | – | – | |

| Brown hawk-owl† | Ninox scutulata | S | 4(2) | 2 (50) | – | 2(0) | 2(0) | 2(0) | |

| Short-eared owl† | Asio flammeus | W | 1(1) | 1 (100) | – | – | 1(1) | – | |

| Caprimulgiformes | Jugle nightjar | Caprimulgus indicus | S | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Coraciiformes | Common kingfisher | Alcedo atthis | R | 2(0) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Piciformes | Japanese pygmy woodpecker | Dendrocopos kizuki | R | 3(3) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Japanese green woodpecker | Picus awokera | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Falconiformes | Common kestrel† | Falco tinnunculus | R | 12(10) | 1 (8.3) | – | 1(0) | – | – |

| Peregrine falcon | Falco peregrinus | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Passeriformes | Bull-headed shrike† | Lanius bucephalus | R | 1(0) | 1 (100) | – | 1(0) | – | – |

| Eurasian jay† | Garrulus glandarius | R | 1(0) | 1 (100) | – | – | 1(0) | – | |

| Azure-winged magpie† | Cyanopica cyanus | R | 2(1) | 2 (100) | 2(1) | – | – | – | |

| Carrion crow† | Corvus corone | R | 12(7) | 6 (50) | 2(2) | 4(0) | 1(0) | 1(0) | |

| Large-billed crow† | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | 10(7) | 7 (70) | 1(0) | 6(3) | 2(1) | 2(1) | |

| Japanese tit† | Parus minor | R | 15(15) | 1 (6.7) | – | – | 1(0) | – | |

| Eurasian skylark | Alauda arvensis | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Brown-eared bulbul† | Hypsipetes amaurotis | R | 21(14) | 6 (28.6) | 4(4) | 2(1) | 2(2) | 2(2) | |

| Barn swallow† | Hirundo rustica | S | 37(26) | 2 (5.4) | – | 1(0) | 1(0) | – | |

| Japanese bush warbler | Cettia diphone | R | 2(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Sakhalin leaf-warbler† | Phylloscopus borealoides | S | 1(0) | 1 (100) | – | 1(0) | – | – | |

| Japanese white-eye | Zosterops japonicus | R | 3(3) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| White-cheeked starling† | Spodiopsar cineraceus | R | 41(36) | 3 (7.3) | 3(1) | – | 1(0) | 2(0) | |

| Japanese thrush† | Turdus cardis | S | 1(1) | 1 (100) | – | 1(1) | 1(1) | 1(1) | |

| Pale thrush | Turdus pallidus | W | 1(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Dusky thrush† | Turdus naumanni | W | 3(3) | 1 (33.3) | – | – | 1(1) | – | |

| Narcissus flycatcher† | Ficedula narcissina | S | 3(1) | 2 (66.7) | – | 1(0) | 1(1) | – | |

| Eurasian tree sparrow† | Passer montanus | R | 31(23) | 3 (9.7) | 1(1) | 1(0) | 1(0) | 1(1) | |

| White wagtail | Motacilla alba | R | 2(2) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Grey-capped greenfinch | Chloris sinica | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Meadow bunting | Emberiza cioides | R | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Black-faced bunting | Emberiza spodocephala | R | 2(0) | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 475(337) | 100(21.1) | 28(16) | 42(15) | 42(21) | 17(5) | ||||

Fig. 1.

Locations of the four facilities in the Kanto region that samples were collected. A. Kanagawa Prefecture Natural Conservation Center, B. Inokashira Animal Hospital, C. Gyotoku Wild Bird Hospital, D. Bird Clinic Kanesaka Animal Hospital.

2.2. DNA extraction and molecular detection of avian haemosporidia

DNA was extracted from blood and liver samples using the standard phenol-chloroform method. The extracted DNA was dissolved in TE solution for nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) which targets the partial mitochondrial cytochrome b (cytb) gene of avian haemosporidia as described (Hellgren et al., 2004). For the 1st PCR, the Haem NFI-Haem NR3 primer set was used. For the 2nd PCR, the HaemF-HaemR2 primer set was used for Plasmodium and Haemoproteus, while HaemFL-HaemR2L primer set for Leucocytozoon (Hellgren et al., 2004). Both PCR reactions were performed in a 25 μL reaction mixture containing 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 10 × ExTaq buffer (Mg2+ free; Takara, Ohtsu, Japan), 0.625U Ex-Taq (Takara), 0.6 μM each primer and 25 ng DNA template. PCR conditions were followed as described previously (Hellgren et al., 2004).

After amplification, the PCR products were visualized using 1.5% agarose gels (Agarose S: Nippon Gene, Chiyoda, Japan) containing ethidium bromide (Nacalai tesque, Nakagyo, Japan). The gels were placed in a chamber containing TAE buffer and electrophoresis was done at 100V for about 20 min. The gels were then visualized under ultraviolet light. Positive samples were cut out of the gel and DNA was extracted using Thermostable β-Agarase (Nippon Gene, Chiyoda, Japan).

The extracted DNA was directly sequenced in both directions using a BigDye™ terminator cycle sequence kit (Ver 3.1 Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA) and an ABI 3130-Avant Auto Sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Double-base callings in the electrophoregram were designated as mixed infections. Nucleotide sequences were aligned using Clustal W program and compared at 479 bp with sequences in the GenBank database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (NCBI website, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and sequences in the MalAvi database (Bensch et al., 2009).

2.3. Analysis of migratory status of collected birds

Each species of bird was classified into one of four migratory statuses in the Kanto region: wintering visitor, migrant breeder, passage visitor and resident breeder, based on the Check-list of Japanese birds, 7th revised edition (Ornithological Society of Japan, 2012). The two introduced species, Mute swan (Cygnus olor) and Northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), were classified as resident breeders. A small population of Eurasian coot (Fulica atra) breeds in the Tokyo area, but most are migratory and use this area as their wintering ground (Hashimoto and Sugawa, 2013). For that reason, the Eurasian coot was considered a winter visitor. We analyzed whether there was a significant difference between migratory statuses, using the chi-square test via Excel. However, because of the small sample size, passage visitors were not used in these tests.

2.4. Microscopic detection of avian haemosporidia

Obtained blood smears were examined under an Olympus BX43 of Olympus IX71 light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The smears were screened at 400× magnification and then carefully examined at 1000× magnification under oil immersion. If a haemosporidia was found, photos were taken with cellSens Standard 1.6 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and were morphologically classified into the proper genera (Valkiūnas, 2005).

3. Results

100 of 475 (21.1%) birds were PCR positive for haemosporidia (Table 1). PCR positive birds consisted of 43 species, including 28 birds for Plasmodium (5.9%), 42 for Haemoproteus (8.8%), 42 for Leucocytozoon (8.8%), and 17 as mixed infection for either different genera or within the same genus.

By migratory status, 30 winter visitors (46.0%), 11 migrant breeders (19.3%), 58 resident breeders (17.0%) and 1 passage visitor (33.3%) were positive (Table 2). Winter visitors were found to have a significantly higher prevalence of detected haemosporidia (χ2 = 28.15, d.f. = 2, p < 0.01). Also, winter visitors showed a significantly higher prevalence of Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon (Plasmodium:χ2 = 17.28, d.f. = 2, p < 0.01; Leucocytozoon:χ2 = 32.33, d.f. = 2, p < 0.01). However, when Eurasian coot (Fulica atra) were removed from analysis, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of Plasmodium (χ2 = 4.20, d.f. = 2, p = 0.12). Also, when Anseriformes were removed from analysis, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of Leucocytozoon (χ2 = 4.67, d.f. = 2, p = 0.10) and when both Eurasian coot and Anseriformes were removed, there was no significant difference in the total prevalence (χ2 = 3.62, d.f. = 2, p = 0.16). Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in Haemoproteus prevalence (χ2 = 1.78, d.f. = 2, p = 0.41).

Table 2.

Number of PCR positive birds by migration status. Passage visitors were removed due to the small sample size. Parentheses show the percentage (%). The asterisk (*) indicates significant differences in accordance to the p value. “Total” shows the total number of infected individuals, counting any co-infections as 1. †is the p-value for Plasmodium sp. when Fulica atra is removed from analysis. ‡is the p-value for Leucocytozoon sp. when Anseriformes are removed from analysis.

| Winter Visitor | Migrant Breeder | Resident Breeder | χ² | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All samples | No. collected | 65 | 65 | 342 | – | – | ||

| No. detected | Plasmodium sp. | 11* | 1 | 16 | 17.28 | <0.01 | 0.12† | |

| Haemoproteus sp. | 4 | 7 | 30 | 0.88 | 0.64 | |||

| Leucocytozoon sp. | 18* | 6 | 19 | 32.33 | <0.01 | 0.10‡ | ||

| total | 30(46.2)* | 11(16.9) | 58(17.0) | 28.83 | <0.01 | |||

In this study, we detected 12, 18 and 26 lineages for Plasmodium, Haemproteus and Leucocytozoon respectively. Of those lineages, 2, 13 and 20 lineages were new and those was assigned names by MalAvi database (Bensch et al., 2009) and accession numbers from GenBank database (NCBI website, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5).

Table 3.

Plasmodium lineages detected and host species that each lineage was detected from. The prevalence of each lineage among all Plasmodium lineage are shown next to the lineage name. Migration status in the Kanto area is shown for each species (W = wintering visitor, S = migrant (summer) breeder, R = resident visitor). Lineages with asterisk (*) indicate lineages derived for the first time. GenBank accession numbers are indicated for those new lineages. Previously reported species of each lineage found in MalAvi are also shown in parentheses.

| Lineage name (prevalence) |

GenBank Accession number |

Bird species | Migration status |

Country (region) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXPIP09 (21.4%) | – | Herring gull | Larus argentatus | W | |

| Azure-winged magpie | Cyanopica cyanus | R | |||

| Carrion crow | Corvus corone | R | |||

| Large-billed crow | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | |||

| (Large-billed crow) | (Corvus macrorhynchos) | R | Japan (Tokyo) | ||

| (Eurasian tree sparrow) | (Passer montanus) | R | Japan (Tokyo) | ||

| CXPIP10 (3.6%) | – | Yellow bittern | Ixobrychus sinensis | S | |

| CXPIP12 (7.1%) | – | Brown-eared bulbul | Hypsipetes amaurotis | R | |

| (Large-billed crow) | (Corvus macrorhynchos) | R | Japan (Tokyo) | ||

| (Hawfinch) | (Coccothraustes coccothraustes) | W | Japan (Tokyo) | ||

| FULATR01* (3.6%) | LC230121 | Eurasian coot | Fulica atra | W | |

| NYCNYC02* (3.6%) | LC230120 | Black-crowned night-heron | Nycticorax nycticorax | R | |

| PADOM02 (3.6%) | – | Eurasian tree sparrow | Passer montanus | R | |

| (House sparrow) | (Passer domesticus) | × | France | ||

| (Ring-necked pheasant) | (Phasianus colchicus) | × | South Korea | ||

| SGS1 (14.3%) [P. relictum] |

– | Brown-eared bulbul | Hypsipetes amaurotis | R | |

| White-cheeked starling | Spodiopsar cineraceus | R | |||

| (Common rosefinch) | (Carpodacus erythrinus) | × | Russia | ||

| (House sparrow) | (Passer domesticus) | × | France | ||

| STVAR04 (3.6%) | – | Common pochard | Aythya ferina | W | |

| (Barred owl) | (Strix varia) | × | United States | ||

| (Blue-winged teal) | (Anas discors) | × | United States | ||

| SW2 (3.6%) [P. homonucleophilum] |

– | Water rail | Rallus aquaticus | W | |

| (Black-faced bunting) | (Emberiza spodocephala) | W | South Korea | ||

| (Tawny owl) | (Strix aluco) | × | Germany | ||

| (Great cormorant) | (Phalacrocorax carbo) | × | Mongolia | ||

| (Corncrake) | (Crex crex) | × | Russia | ||

| SW5 (28.6%) [P. circumflexum] |

– | Mallard | Anas platyrhynchos | W | |

| Great crested grebe | Podiceps cristatus | W | |||

| Eurasian coot | Fulica atra | W | |||

| Streaked shearwater | Calonectris leucomelas | R | |||

| (Great reed warbler) | (Acrocephala arundinaceus) | × | Sweden | ||

| (Northern pintail) | (Anas acuta) | W | US | ||

| (Corncrake) | (Crex crex) | × | Russia | ||

| (Red-crowned crane) | (Grus japonensis) | R | Japan (Hokkaido) | ||

| UPUPA02 (3.6%) | – | Oriental turtle-dove | Streptopelia orientalis | R | |

| (Eurasian hoopoe) | (Upupa epops) | × | Portugal | ||

| YWT4 (3.6%) | – | White-cheeked starling | Spodiopsar cineraceus | R | |

| (White wagtail) | (Motacilla flava) | × | Bulgaria | ||

| (Southern red bishop) | (Euplectes orix) | × | South Africa | ||

Table 4.

Haemoproteus lineages detected and host species that each lineage was detected from. The prevalence of each lineage among all Haemoproteus lineage are shown next to the lineage name. Migration status in the Kanto area is shown for each species (W = wintering visitor, S = migrant (summer) breeder, P = passage visitor, R = resident visitor). Lineages with asterisk (*) indicate lineages derived for the first time. GenBank accession numbers are indicated for those new lineages. Previously reported species of each lineage found in MalAvi are also shown in parentheses.

| Lineage name (prevalence) |

GenBank Accession number |

Bird species | Migration status |

Country (region) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COCOR14* (4.9%) | LC230128 | Carrion crow | Corvus corone | R | |

| COCOR15* (7.3%) | LC230130 | Carrion crow | Corvus corone | R | |

| Large-billed crow | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | |||

| CORMAC04* (4.9%) | LC230129 | Large-billed crow | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | |

| CXPIP19 (7.3%) | – | Carrion crow | Corvus corone | R | |

| Large-billed crow | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | |||

| FICNAR01* (2.4%) | LC230125 | Narcissus flycatcher | Ficedula narcissina | S | |

| HYPHI07 (7.3%) | – | Brown-eared bulbul | Hypsipetes amaurotis | R | |

| Sakhalin leaf-warbler | Phylloscopus borealoides | S | |||

| (Philippine bulbul) | (Ixos philippinus) | × | Philippines | ||

| LARCRA01 (9.8%) | – | Black-tailed gull | Larus crassirostris | R | |

| Common gull | Larus canus | W | |||

| Common kestrel | Falco tinnunculus | R | |||

| (Caspian gull) | (Larus cachinnans) | × | Spain | ||

| LARCRA02* (2.4%) | LC230123 | Black-tailed gull | Larus crassirostris | R | |

| NINOX06* (2.4%) | LC230131 | Brown hawk-owl | Ninox scutulata | S | |

| NINOX07* (2.4%) | LC230132 | Brown hawk-owl | Ninox scutulata | S | |

| NUMPHA01* (2.4%) | LC230122 | Whimbrel | Numenius phaeopus | S | |

| OTULEM01* (7.3%) | LC230124 | Sunda scops owl | Otus lempiji | R | |

| Grey heron | Ardea cinerea | R | |||

| Eurasian woodcock | Scolopax rusticola | W | |||

| OTULEM02* (2.4%) | LC230133 | Sunda scops owl | Otus lempiji | R | |

| PLAMIN01* (19.5%) | LC230126 | Black-faced spoonbill | Platalea minor | P | |

| Ural owl | Strix uralensis | R | |||

| Bull-headed shrike | Lanius bucephalus | R | |||

| Eurasian tree sparrow | Passer montanus | R | |||

| STRORI01 (4.9%) | – | Oriental turtle-dove | Streptopelia orientalis | R | |

| (Oriental turtle-dove) | (Streptopelia orientalis) | R | Japan (Hokkaido) | ||

| STRURA01* (2.4%) | LC230127 | Ural owl | Strix uralensis | R | |

| STRURA02* (7.3%) | LC230134 | Ural owl | Strix uralensis | R | |

| Barn swallow | Hirundo rustica | S | |||

| TUCHR01 (2.4%) [H. minutus] |

– | Japanese thrush | Turdus cardis | S | |

| (Song thrush) | (Turdus philomelos) | × | Russia | ||

| (Chinese thrush) | (Turdus mupinensis) | × | China | ||

| (Redwing) | (Turdus iliacus) | × | Sweden | ||

Table 5.

Leucocytozoon lineages detected and host species that each lineage was detected from. The prevalence of each lineage among all Leucocytozoon lineage are shown next to the lineage name. Migration status in the Kanto area is shown for each species (W = wintering visitor, S = migrant (summer) breeder, R = resident visitor). Lineages with asterisk (*) indicate lineages derived for the first time. GenBank accession numbers are indicated for those new lineages. Previously reported species of each lineage found in MalAvi are also shown in parentheses.

| Lineage name (prevalence) |

GenBank Accession number |

Bird species | Migration status |

Country (region) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIXGAL01* (4.9%) | LC230144 | Mandarin duck | Aix galericulata | W | |

| ANACRE02 (2.4%) | – | Falcated duck | Anas falcata | W | |

| (Green-winged teal) | (Anas crecca) | W | Japan (Hokkaido) | ||

| ANACU04 (4.9%) | – | Northern pintail | Anas acuta | W | |

| (Northern pintail) | (Anas acuta) | W | United States | ||

| ASIFLA01* (2.4%) | LC230137 | Short-eared owl | Asio flammeus | W | |

| CIAE02 (4.9%) | – | Great crested grebe | Podiceps cristatus | W | |

| Brown hawk-owl | Ninox scutulata | S | |||

| (Black kite) | (Milvus migrans) | × | Spain | ||

| (Corncrake) | (Crex crex) | × | Russia | ||

| (Besra) | (Accipiter virgatus) | × | Philippines | ||

| COCOR10 (4.9%) | – | Eurasian jay | Garrulus glandarius | R | |

| Brown-eared bulbul | Hypsipetes amaurotis | R | |||

| (Hawfinch) | (Coccothraustes coccothraustes) | W | Japan (Hokkaido) | ||

| COCOR16* (2.4%) | LC230140 | Carrion crow | Corvus corone | R | |

| CORMAC05* (2.4%) | LC230139 | Large-billed crow | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | |

| CORMAC06* (2.4%) | LC230141 | Large-billed crow | Corvus macrorhynchos | R | |

| FICNAR02* (2.4%) | LC230145 | Narcissus flycatcher | Ficedula narcissina | S | |

| GORGOI03* (2.4%) | LC230143 | Japanese night heron | Gorsachius goisagi | S | |

| HIRUS16* (2.4%) | LC230147 | Barn swallow | Hirundo rustica | S | |

| HYPAM03* (2.4%) | LC230142 | Brown-eared bulbul | Hypsipetes amaurotis | R | |

| NINOX08* (2.4%) | LC230151 | Brown hawk-owl | Ninox scutulata | S | |

| OTULEM03* (4.9%) | LC230135 | Sunda scops owl | Otus lempiji | R | |

| OTULEM04* (2.4%) | LC230136 | Sunda scops owl | Otus lempiji | R | |

| OTULEM05* (2.4%) | LC230138 | Sunda scops owl | Otus lempiji | R | |

| PARMIN01* (2.4%) | LC230146 | Japanese tit | Parus minor | R | |

| SCORUS01* (2.4%) | LC230149 | Eurasian woodcock | Scolopax rusticola | W | |

| SPOCIN01* (2.4%) | LC230150 | White-cheeked starling | Spodiopsar cineraceus | R | |

| STRORI04* (9.8%) | LC230148 | Oriental turtle-dove | Streptopelia orientalis | R | |

| White-bellied green-pigeon | Treron sieboldii | R | |||

| Eurasian tree sparrow | Passer montanus | R | |||

| STRORI05* (4.9%) | LC230152 | Oriental turtle-dove | Streptopelia orientalis | R | |

| White-bellied green-pigeon | Treron sieboldii | R | |||

| TUCAR02* (2.4%) | LC230154 | Japanese thrush | Turdus cardis | S | |

| TURNAU01* (2.4%) | LC230153 | Dusky thrush | Turdus naumanni | W | |

| TUSW03 (2.4%) | – | Common teal | Anas crecca | W | |

| (Common teal) | (Anas crecca) | × | United States | ||

| TUSW04 (17.1%) | – | Northern pintail | Anas acuta | W | |

| Common teal | Anas crecca | W | |||

| Tufted duck | Aythya fuligula | W | |||

| Greater scaup | Aythya marila | W | |||

| (Bar-headed goose) | (Anser indicus) | × | Mongolia | ||

| (Great cormorant) | (Phalacrocorax carbo) | × | Mongolia | ||

| (Tundra swan) | (Cygnus columbianus) | × | United States | ||

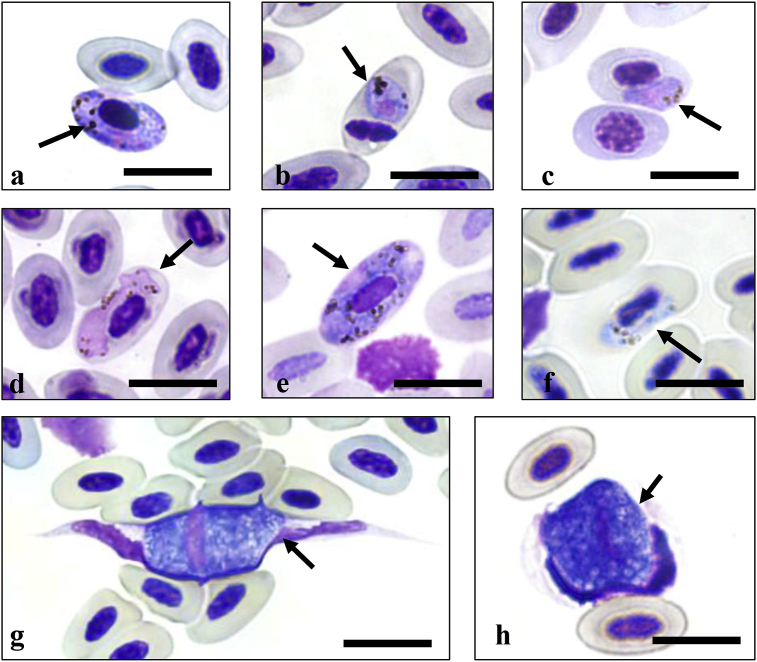

Gametocytes of Plasmodium, Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon were observed in 48 of the 337 blood smears (Fig. 2), but in 12 blood smears from PCR positive birds, there were no detectable protozoa (Table 1). For 40 PCR positive birds, blood smears were unavailable and morphological identifications were not capable. No haemosporidia were detected in the 277 blood slides from PCR negative birds. Some gametocytes were morphologically identified to the species level including P. relictum, P. circumflexum and H. minutus. These showed identical results of species identification by both DNA and morphology (Fig. 2 b, c, f) (Valkiūnas, 2005).

Fig. 2.

Hemacolor® stained blood smears from rescued birds: (a) Plasmodium sp. from Cyanopica cyanus, (b) P. reluctum from Hypisipetes amaurotis, (c) P. circumflexum from Fulica atra, (d) Haemoproteus sp. from Hypisipetes amaurotis, (e) Haemoproteus sp. from Larus canus, (f) H. minutus from Turdus cardis, (g) Leucocytozoon sp. from Anas acuta, (h) Leucocytozoon sp. from Aythya marila.

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence among rescued birds

In this study, the overall prevalence of avian haemosporidia was 21.1%, higher than previously reported in Japan (10.6–14.9%) (Murata, 2002, Nagata, 2006, Imura et al., 2012, Yoshimura et al., 2014). However, it is difficult to directly compare this study with others, as several conditions such as detection method, target species, location and other factors were different. For example, Nagata (2006) did not include Leucocytozoon for analysis. Another study showed very high prevalence of 59.6%, assumedly due to the high bird and mosquito density in Minami Daitō Island of Okinawa prefecture (Murata et al., 2008b). Also, it is well known that prevalence greatly differs among avian species because of the difference in immune responses, habitat and various other factors (Imura et al., 2012, Quillfeldt et al., 2011, Valkiūnas, 2005, Yoshimura et al., 2014). Lastly, an important factor that needs to be discussed is the fact that these samples are from injured and rescued wild birds. These birds were rescued for various reasons (e.g. window collision, immobility and injury) and tend to have symptoms such as concussion, bone fracture and anemia. Body condition factors and immune reactions were not tested in this study, but in previous studies, there are reports that birds in poor body conditions are more likely to be infected by parasites compared to healthy birds, although there is variation between species (Dawson and Bortolotti, 2000, Meixell et al., 2016, Fleskes et al., 2017). It is however difficult to distinguish whether the individual is more likely to get infected when body conditions are poor, or vice versa. Also, some individuals stay in the facilities for long terms, depending on the type and degree of injury or condition. This means that those individuals have a higher chance of getting infected within the facility. Because of the general lack of data on the genetic diversity of avian malaria in Japan, it is difficult to separate individuals that were infected before and after being rescued. It is therefore important to achieve samples as soon as possible after the birds are rescued.

4.2. Analysis of migratory status

Overall, the prevalence among migratory birds (i.e. wintering visitors, migratory breeders, passage visitors) was higher compared to resident breeders, being 31.6% and 17.0% respectively. Notably, in both Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon, the prevalence of avian haemosporidia was significantly higher in wintering visitors, birds that breed north of the Kanto region and migrate to the Kanto region in the winter (Table 2). The haemosporidia prevalence of birds in the Russian Far East is very high (63.9%), where a high proportion of wintering visitors from the Kanto region migrate for breeding. This high prevalence is thought to be due to the high density of vectors in the Russian Far East (Palinauskas et al., 2005). Bloodsucking activities of vectors in the Tundra and northern areas are more rigorous compared to lower latitudes (Rubtsov, 1990). For these reasons, there is a high chance that wintering visitors were infected in their breeding grounds, where they have a high contact with the vectors due to high vector densities. However, the high prevalence is Russian Far East is seen across all 3 genera of haemosporidia (Palinauskas et al., 2005), which is incoherent with the fact that there was no significant difference in migratory and resident prevalence for Haemoproteus.

When Eurasian coot (Fulica atra) and Anseriformes were removed from analysis, there was no significant difference among migratory status in Plasmodium sp. and Leucocytozoon sp., respectively. Furthermore, when both were removed from data set for analysis, there was no significant difference in the overall prevalence. These might show that the significantly high prevalence in wintering visitors was due to a bias caused by these species. There are few reports of the prevalence in Eurasian coot, but the Leucocytozoon prevalence in Anseriformes is known to be high (Ramey et al., 2015, Reeves et al., 2015, Meixell et al., 2016, Fleskes et al., 2017). Reasons are not sufficiently discussed, but probable reasons are due to differences in immune response, habitat environment, host specificity and occurring vector species (Valkiūnas, 2005, Quillfeldt et al., 2011, Imura et al., 2012, Yoshimura et al., 2014). The prevalence in Ural owls (Strix uralensis) was particularly high compared to other species, presumably due to similar reasons as mentioned above. While certain patterns in migratory statuses may be seen and possibilities such as vector abundance and fauna exposure cannot be ruled out, general surveys such as this study need to be aware and careful of biases that may come from host specific factors.

4.3. Analysis of Plasmodium lineages

12 Plasmodium lineages were found in this study (Table 3). Of these, 3 lineages were detected solely or mainly from wintering visitors. Plasmodium lineage SW5, classified as P. circumflexum, and SW2, classified as P. homonucleophilum, have been recorded from various parts of the world and are thought to be transmitted by Culiseta spp. mosquitoes (Meyer and Bennett, 1976, Valkiūnas, 2005, Ejiri et al., 2011a). Culiseta spp. are found in the holarctic (Medvedev, 2009), but in Japan, the only known species (C. kanayamensis and C. nipponica) are found solely in Aomori and Hokkaido prefectures (Ono, 1969, Ejiri et al., 2011b, Maekawa et al., 2016), the northern-most parts of Japan. Although there have been no reports of avian malaria from Culiseta spp. in Japan, Stellar's sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) and other bird DNA were detected from this mosquito genus (Ejiri et al., 2011b). Also, in a previous study, SW5 was reported in Red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis) (Yoshimura et al., 2014), a resident breeder that is found only in Hokkaido, Japan. Thus, the lineages SW2 and SW5 might be transmitted in Northern Japan of further north. Interestingly, a new lineage FULATR01 found from Eurasian coot (Fulica atra) in this study was very close to SW2 (difference of only one base). If such difference is small enough to maintain the same lifecycle including vector species, this lineage may also only be transferred in the far north. Most individuals of Eurasian coot, which both FULATR01 and SW5 were detected, are wintering visitors in the Kanto region and breed in Northern Japan. However, there is a small population that breeds in the Kanto region (Hashimoto and Sugawa, 2013). In the Kanto region, avian blood has been detected from infected mosquitoes, meaning that the host-vector-parasite lifecycle is preserved in this area (Ejiri et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2009). We were not able to distinguish whether the individuals in this study were migratory or resident individuals, but due to the possible vector specificity of these lineages, there is a high possibility that the individuals in this study are migratory and were infected in areas further north. However, there is a possibility that there are vector species other than Culiseta spp. that are capable of transmitting these discussed species of Plasmodium. Further research is needed to justify this hypothesis. Of the high percentage of SW5 found in this study, the majority (5 of 8 individuals) were from Eurasian coot. Some lineages are known to have low host specificity and yet still have a high prevalence in a certain species (Hellgren et al., 2009), which may be the case for this lineage.

4 lineages (PADOM02, SGS1, UPUPA02 and YWT4) were found from resident breeders and have previously been reported from host species of other countries. SGS1 has been detected from vectors across many countries including 3 mosquito species (Culex sasai, Cx. pipiens and Lutzia vorax) in Japan and is known to have a wide vector, host and geographical range (Tsuda, 2017). The vector species of the other 3 lineages have not been found in Japan, but also have a high chance that they may be wide-ranged lineages. The lineage CXPIP10 from Yellow bittern (Ixobrychus sinensis) was detected from an avian host for the first time. This lineage has been previously detected in Culex spp. of Spain and Japan (Tsuda, 2017). Because of insufficient host information, the range of this lineage is unknown, but there is a high possibility that it is transmitted between vector and host in Japan.

2 lineages (CXPIP09 and CXPIP12) were found from resident breeders and have been previously detected from mosquito species in Japan (Ejiri et al., 2009, Ejiri et al., 2011b, Kim and Tsuda, 2010). Large-billed crow (Corvus macrorhynchos) and Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus) were detected from the blood-meal of CXPIP09-infected mosquitoes (Kim and Tsuda, 2010) and this lineage made up over 21.4% of all the Plasmodium lineages found in this study. This highly suggests that this lineage is highly preserved among the avian hosts and mosquito vectors of Japan. These lineages have only been found in Japan, meaning that they are perhaps unique lineages of Japan. CXPIP09 was found from 1 Herring gull (Larus argentatus), a winter visitor species, which had been in the facility for 3 years. This strongly suggests that this individual was infected within the facility. Meanwhile, CXPIP12 had been detected in a previous study from Hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes), also a winter visitor. As the mosquito population density is known to decline in the Kanto area during the winter (Kim and Tsuda, 2010), the chances of this species to get infected in the Kanto area are low. Hawfinch are known to breed as south as Nagano prefecture, a neighboring prefecture right next to the Kanto region (Ornithological Society of Japan, 2012) and may have been infected in such areas. 1 new lineage NYCNYC02 was found in Black-crowned night-heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), which are mostly sedentary, but some individuals are known migrate to the Philippines (Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, 2002, Ornithological Society of Japan, 2012). Though these lineages may be unique lineages of Japan, the range of vector species such as Culex pipiens is very wide, including Russia (Medvedev, 2009) and there is a significant exchange of birds between Japan and the surrounding continents, meaning there is a possibility that these lineages may be found in other areas of the world.

4.4. Analysis of Haemoproteus lineages

18 Haemoproteus lineages were found in this study (Table 4). 3 of these lineages were previously found in other countries, suggesting a wide distribution. Of these, TUCHR01 was found from Japanese thrush (Turdus cardis), being of the same genus as all the previous hosts. Although not as strict as Leucocytozoon, Haemoproteus is known to have host specificity to a certain degree. Moreover, this lineage, which belongs to the species H. minutus, is known to have high specificity in thrush (Valkiūnas, 2005, Palinauskas et al., 2013). This study is hence supportive of this specificity.

For all the remaining lineages, except for 1 with a single previous detection within Japan, there is no vector or avian information regarding distribution or transmission. This is in part due to the fact that most of the lineages were detected for the first time. There are very few previously reported lineages of Haemoproteus in Japan, although reasons are unknown. Also, while there are at least 82 known species of Culicoides spp. in Japan (Yanase et al., 2014), there have been no studies regarding haemosporidian infection in Culicoides spp. or any other biting midge genus. However, 11 of these lineages were detected from resident breeders, strongly suggesting that these lineages are transmitted within Japan. For the 4 lineages derived solely from migratory breeders, further sampling and studies on both the vector and host species are needed for any further speculations.

It is interesting to note that there were no lineages found solely from wintering visitors, unlike Plasmodium and Leucocytozoon. In the other 2 genera, there were many lineages from wintering visitors, but tended to be of a specific host species or order. There is a possibility that such host specific lineages of Haemoproteus were simply not sampled in this study. Of the 4 wintering visitors infected with Haemoproteus, only 2 were identified to a specific lineage due to co-infection. The 2 lineages from wintering visitors were also found from resident breeders. There are three possibilities for these lineages. One is that they were infected in their breeding grounds. LARCRA01 has been previously detected in Spain from Caspian gull (Larus cachinnans), which suggests that this lineage has a wide distribution, as mentioned above. Another possibility is that they were infected within the facilities, also discussed earlier. The last possibility is that they were infected in Japan during the winter. Seasonal dynamics of Culicoides spp. have been studied in other countries and generally, they agree that there are no active Culicoides spp. from November to April (Ander et al., 2012, Santiago-Alarcon et al., 2013). However, another study found parous biting midges in February, suggesting that bloodsucking activities occur even during the winter (Mayo et al., 2014). Although the seasonality for Culicoides spp. in Japan is unknown, there is a possibility that Haemoproteus may be transmitted even during the winter. In order to do any further discussion, more information regarding Haemoproteus, including the identification of vector species, is needed.

4.5. Analysis of Leucocytozoon lineages

8 lineages of Leucocytozoon were detected from only wintering visitors (Table 5). Of these, 5 lineages were detected solely from Anseriformes, which are all wintering visitors in the Kanto area and have a widespread breeding zone from Europe to Russian Far East (Brazil, 2009, Ornithological Society of Japan, 2012). Transmission of the parasite can take place at both the breeding and wintering sites of the avian host as long as the vector is active (Waldenström et al., 2002, Valkiūnas, 2005). There have been no studies regarding the ecology and prevalence of haemosporidia in blackflies of Japan. Although the seasonal dynamics of blackflies, which are thought to be the vectors of Leucocytozoon, in this area are poorly studied, bloodsucking activities are known to decline when temperatures decrease lower than 10 °C (Crosskey, 1990). The average temperature of the Kanto region from December to February in the years 1981–2010 was 7.6 °C, with the highest being 11.9 °C (Japan Meteorological Agency; http://www.data.jma.go.jp) suggesting that blackflies cannot be active during the winter. However, other studies reveal the possibility of bloodsucking activities in the winter (Saito et al., 1986, Rubtsov, 1989). Saito et al. (1986) collected over 1000 blackflies in Tokyo prefecture in five samplings days from November to February, although bloodsucking activities were not checked. Rubtsov (1989) stated that although low temperature inhibits adult blackfly emergence and bloodsucking activities in northern areas, some blackflies in lower latitudes can be active for bloodsucking in late autumn to winter. It is therefore difficult to distinguish whether bloodsucking activities take place during the winter in the Kanto region. However, lineage TUSW04 has also been found in Mongolia from Bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) and continental subspecies of Great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo), which breed in continental East Asia and are accidental visitors in Japan (Brazil, 2009). Hence, it is more likely that these lineages were infected at their breeding grounds in Northern Japan or continental Asia. ANACU04 has been previously found from Northern pintail (Anas acuta) of North America, which are known to change their wintering grounds between Japan and North America depending on year (Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, 2002, Nicolai et al., 2005). This supports the fact that the same lineage was found from Anatidae in Japan and North America, suggesting that Anatidae have an important role in the transmission of parasites between continents (Ramey et al., 2015). It is essential to note again the fact that some of the birds were rescued a year or more before sampling, giving the possibility that they were infected in the facilities, rather than in their breeding grounds.

1 lineage, CIAE02, was detected from a wintering visitor and migratory breeder. This lineage has been previously seen in other countries. It is difficult to distinguish the area and distribution of transmission, as there is no vector information. However, because there have been many reports from various countries and various hosts, it is possible that this species is transmitted across a wide range. Meanwhile, COCOR10 shows a similar pattern to the Plasmodium lineage CXPIP12, being previously found in Hawfinch. Although the distribution range for this lineage is unknown, it is safe to say that this lineage is transmitted in Japan, as it has been found in resident breeders.

For the remaining 16 lineages from resident and migratory breeders, there is little information, as they were all detected for the first time. For the 11 lineages from resident breeders, there is a high possibility that they are transmitted within Japan. However, for the 5 of the lineages were found from migratory breeders, it is difficult to identify the location of transmission. Further studies on the possible vector species are needed in order to justify this. Although Leucocytozoon is known to have strong host specificity, apparent lineages with high host specificity were not found due to the fact that the majority of the lineages were described for the first time or have few reports of previous hosts. However, TUSW04 seems to have high host specificity in Anseriformes.

In this study, we were able to determine the prevalence of haemosporidia of rescued wild birds in the Kanto area. Although rescued wild birds are not truly in their natural state, they are important samples to survey the prevalence of avian haemosporidia in wild birds of the Kanto region. Migratory birds have a chance of coming in contact with various different haemosporidia that are distributed in areas they migrate, hence making them important carriers for the distribution and dispersal of haemosporidia. Meanwhile, the appropriate vector differs among species of haemosporidia and the presence of the appropriate vector is a key factor for transmission. Influence on the changes in distribution due to climate changes are reported in both the avian hosts and arthropod vectors, therefore emphasizing the need to monitor their ecology in order to prevent infectious diseases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. T. Sato of Gyotoku Wild Bird Hospital, Dr. T. Ishibashi of Inokashira Animal Hospital, Dr. H. Kanesaka of Bird Clinic Kanesaka Animal Hospital, staff of Kanagawa Prefecture Natural Conservation Center for their kind supply of samples. Ms. W. Kato and Mr. K. Nakamura, members of our laboratory contributed greatly for collecting and analyzing the numerous bird samples. We also appreciate Dr. Ravinder N. M. Sehgal of San Francisco State University for his great contribution to improve this manuscript with very helpful suggestions. This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI no. 26450484) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Strategic Research Base Development Program “International Research on the Management of Zoonosis in Globalization and Training for Young Researchers” from the MEXT of Japan; and Nihon University Research Grant.

References

- Ander M., Meiswinkel R., Chirico J. Seasonal dynamics of biting midges (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae: Culicoides), the potential vectors of bluetongue virus, in Sweden. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;184:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C.T., Lapointe D.A. Introduced avian diseases, climate change, and the future of hawaiian honeycreepers. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2009;23:53–63. doi: 10.1647/2008-059.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensch S., Hellgren O., Pérez-Tris J. MalAvi: a public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009;9:1353–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazil M. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 2009. Birds of East Asia: China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno M.G., Lopez R.P.G., Tironi de Menezes R.M., Costa-Nascimento M. de J., Lima G.F.M. de C., Araujo R.A. de S., Vaz Guida F.J., Kirchgatter K. Identification of Plasmodium relictum causing mortality in penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) from São Paulo Zoo, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;173:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosskey R.W. John Vlfiley & Sons; Chichester: 1990. The Natural History of Blackflies. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson R.D., Bortolotti G.R. Effect of hematozoan parasites on condition and return rates of American kestrels. Auk. 2000;117:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ejiri H., Sato Y., Kim K.S., Tamashiro M., Tsuda Y., Toma T., Miyagi I., Murata K., Yukawa M. First record of avian Plasmodium DNA from mosquitoes collected in the Yaeyama Archipelago, southwestern border of Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2011;73:1521–1525. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiri H., Sato Y., Kim K.S., Tsuda Y., Murata K., Saito K., Watanabe Y., Shimura Y., Yukawa M. Blood meal identification and prevalence of avian malaria parasite in mosquitoes collected at Kushiro Wetland, a subarctic zone of Japan. J. Med. Entomol. 2011;48:904–908. doi: 10.1603/me11053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiri H., Sato Y., Sawai R., Sasaki E., Matsumoto R., Ueda M., Higa Y., Tsuda Y., Omori S., Murata K., Yukawa M. Prevalence of avian malaria parasite in mosquitoes collected at a zoological garden in Japan. Parasitol. Int. 2009;105:629–633. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbers A.R.W., Koenraadt C.J.M., Meiswinkel R. Mosquitoes and Culicoides biting midges: vector range and the influence of climate change. Rev. Int. Epizoot. 2015;34:123–137. doi: 10.20506/rst.34.1.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleskes J.P., Ramey A.M., Reeves A.B., Yee J.L., Fleskes J.P., Yee J.L., Ramey A.M., Reeves A.B. Body mass, wing length, and condition of wintering ducks relative to hematozoa infection. J. Fish. Wildl. Manag. 2017;8:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Garamszegi L.Z. Climate change increases the risk of malaria in birds. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011;17:1751–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H., Sugawa H. Population trends of wintering eurasian coot Fulica atra in East Asia. Ornithol. Sci. 2013;12:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren O., Pérez-Tris J., Bensch S. A jack-of-all-trades and still a master of some: prevalence and host range in avian malaria and related blood parasites. Ecology. 2009;90:2840–2849. doi: 10.1890/08-1059.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren O., Waldenström J., Bensch S. A new Pcr assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. 2004;90:797–802. doi: 10.1645/GE-184R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi H., Koike S., Shigeta M. Effects of climate change on the phenology, distribution, and population of organisms. Chikyu Kankyo. 2009;14:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Imura T., Suzuki Y., Ejiri H., Sato Y., Ishida K., Sumiyama D., Murata K., Yukawa M. Prevalence of avian haematozoa in wild birds in a high-altitude forest in Japan. Vet. Parasitol. 2012;183:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.S., Tsuda Y. Seasonal changes in the feeding pattern of Culex pipiens pallens govern the transmission dynamics of multiple lineages of avian malaria parasites in Japanese wild bird community. Mol. Ecol. 2010;19:5545–5554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.S., Tsuda Y., Yamada A. Bloodmeal identification and detection of avian malaria parasite from mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) inhabiting coastal areas of Tokyo Bay. Jpn. J. Med. Entomol. 2009;46:1230–1234. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa Y., Tsuda Y., Sawabe K. A nationwide survey on distribution of mosquitoes in Japan (Japanese) Med. Entomol. Zool. 2016;67:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo C.E., Osborne C.J., Mullens B.A., Gerry A.C., Gardner I.A., Reisen W.K., Barker C.M., Maclachlan N.J. Seasonal variation and impact of waste-water lagoons as larval habitat on the population dynamics of Culicoides sonorensis (Diptera:Ceratpogonidae) at two dairy farms in northern California. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev S. The fauna of bloodsucking insects of Northwestern Russia. Characteristics of the ranges. Entomol. Rev. 2009;89:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Meixell B.W., Arnold T.W., Lindberg M.S., Smith M.M., Runstadler J.A., Ramey A.M. Detection, prevalence, and transmission of avian hematozoa in waterfowl at the Arctic/sub-Arctic interface: co-infections, viral interactions, and sources of variation. Parasit. Vectors. 2016;9:390. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1666-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C.L., Bennett G.F. Observations on the sporogony of Plasmodium circumflexum Kikuth and Plasmodium polare Manwell in New Brunswick. Can. J. Zool. 1976;54:133–142. doi: 10.1139/z76-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K. Study on avian haemosporidian parasites in Japanese wild birds. J. Anim. Protozooses. 2007;22:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Murata K. Prevalence of blood parasites in Japanese wild birds. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2002;64:785–790. doi: 10.1292/jvms.64.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Nii R., Sasaki E., Ishikawa S., Sato Y., Sawabe K., Tsuda Y., Matsumoto R., Suda A., Ueda M. Plasmodium (Bennettinia) juxtanucleare infection in a captive white eared-pheasant (Crossoptilon crossoptilon) at a Japanese zoo. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2008;70:203–205. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Nii R., Yui S., Sasaki E., Ishikawa S., Sato Y., Matsui S., Horie S., Akatani K., Takagi M., Sawabe K., Tsuda Y. Avian haemosporidian parasites infection in wild birds inhabiting minami-daito Island of the northwest Pacific. Jpn. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2008;70:501–503. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Tamada A., Ichikawa Y., Hagihara M., Sato Y., Nakamura H., Nakamura M., Sakanakura T., Asakawa M. Geographical distribution and seasonality of the prevalence of Leucocytozoon lovati in Japanese rock ptarmigans (Lagopus mutus japonicus) found in the alpine regions of Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2007;69:171–176. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata H. Reevaluation of the prevalence of blood parasites in Japanese Passerines by using PCR based molecular diagnostics. Ornithol. Sci. 2006;5:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai C.A., Flint P.L., Wege M.L. Annual survival and site fidelity of northern pintails banded on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska. J. Wildl. Manag. 2005;69:1202–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Olias P., Wegelin M., Zenker W., Freter S., Gruber A.D., Klopfleisch R. Avian malaria deaths in parrots, Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:950–952. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono H. On the mosquitoes at tokachi prefecture in Hokkaido (Japanese) Res. Bull. Obihiro Univ. 1969;6:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ornithological Society of Japan . 7th revised edition. Gakken; Sanda: 2012. Check-list of Japanese Birds. [Google Scholar]

- Palinauskas V., Iezhova T.A., Križanauskienė A., Markovets M.Y., Bensch S., Valkiūnas G. Molecular characterization and distribution of Haemoproteus minutus (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae): a pathogenic avian parasite. Parasitol. Int. 2013;62:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinauskas V., Markovets M.Y., Kosarev V.V., Efremov V.D., Sokolov L.V. Occurrence of avian haematozoa in Ekaterinburg and Irkutsk districts of Russia. EKOLOGIJA. 2005;4:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Quillfeldt P., Arriero E., Martínez J., Masello J.F., Merino S. Prevalence of blood parasites in seabirds - a review. Front. Zool. 2011;8:26–35. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey A.M., Schmutz J.A., Reed J.A., Fujita G., Scotton B.D., Casler B., Fleskes J.P., Konishi K., Uchida K., Yabsley M.J. Evidence for intercontinental parasite exchange through molecular detection and characterization of haematozoa in northern pintails (Anas acuta) sampled throughout the North Pacific Basin. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015;4:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A.B., Smith M.M., Meixell B.W., Fleskes J.P., Ramey A.M. Genetic diversity and host specificity varies across three genera of blood parasites in ducks of the Pacific Americas flyway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsov I.A. second ed. E.J. Brill; Leiden: 1990. Fauna of the USSR Diptera Volume 6, Part 6: Blackflies (Simuliidae) [Google Scholar]

- Saito K., Kanayama A., Sato H., Ogata K. Studies on the ecology of blackflies (Diptera:Simuliidae). VIII. Fauna of the blackflies in Tokyo metropolis (Japanese) Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 1986;30:144–146. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Alarcon D., Havelka P., Pineda E., Segelbacher G., Schaefer H.M. Urban forests as hubs for novel zoonosis: blood meal analysis, seasonal variation in Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) vectors, and avian haemosporidians. Parasitol. 2013;140:1799–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013001285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Hagihara M., Yamaguchi T., Yukawa M., Murata K. Phylogenetic comparison of Leucocytozoon spp. from wild birds of Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2007;69:55–59. doi: 10.1292/jvms.69.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa M., Sato Y., Ejiri H. Molecular identification of avian haemosporidia in wild birds and mosquitoes on Tsushima Island. Jpn. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2012;75:319–326. doi: 10.1292/jvms.12-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda Y. Review on recent studies on avian malaria parasites and their vector mosquitoes (Japanese) Med. Entomol. Zool. 2017;68:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Valkiūnas G. CRC Press; 2005. Avian Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia. [Google Scholar]

- Van Riper C.I., Van Riper S.G., Goff M.L., Laird M. The epizootiology and ecological significance of malaria in hawaiian land birds. Ecol. Monogr. 1986;56:327–344. [Google Scholar]

- Waldenström J., Bensch S., Kiboi S., Hasselquist D., Ottoson U. Cross-species infection of blood parasites between resident and migratory songbirds in Africa. Mol. Ecol. 2002;11:1545–1554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashina Institute for Ornithology . 2002. Atlas of Japanese Migratory Birds from 1961 to 1995 (Japanese) (Tokyo) [Google Scholar]

- Yanase T., Hayama Y., Shirafuji H., Yamakawa M., Kato T., Horiwaki H., Tsutsui T., Terada Y. Development of a light trap with light-emmiting diodes (LEDs) for the collection of Culicoides biting midges (Japanese) Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2014;58:127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura A., Koketsu M., Bando H., Saiki E., Suzuki M., Watanabe Y., Kanuka H., Fukumoto S. Phylogenetic comparison of avian haemosporidian parasites from resident and migratory birds in Northern Japan. J. Wildl. Dis. 2014;50:235–242. doi: 10.7589/2013-03-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]